Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory disease which may significantly impact health status. To reduce symptoms and improve quality of life, pharmacological treatment should be complemented by addressing extrapulmonary traits and lifestyle- and psychosocial factors, such as physical deconditioning, decrease in muscle mass, smoking or depression. Treatment of these non-pharmacological traits is commonly conducted in a primary care setting and often requires multiple healthcare providers (HCPs). To provide complementary care, high quality interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is required. Therefore, our aim was to develop an IPC model for COPD patients treated in primary care. To achieve our aims, we used co-creation sessions (CCS), a recognised method within the participatory action research (PAR) approach. Co-creation, characterised by collaboration and a bottom-up strategy, has repeatedly shown to be suitable for developing care improvements. We recruited two independent groups of stakeholders to participate in six CCS in parallel. They were purposefully sampled and included patients and HCPs from both primary and secondary/tertiary care. Given the considerable overlap in results between the two independent teams, we developed a joint model which is ready to be pilot tested. Our model is based on current and local work methods and can be implemented in existing local contexts and structures. We noted some differences between the teams: the choice of the routing and timing of IPC commencement, and the choice for the communication platform. Using the PAR approach and co-creation, we developed an actionable IPC model in primary care for COPD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, complex, and heterogeneous chronic respiratory disease causing a significant burden to both the affected individual and society1,2,3,4. Although COPD is incurable, it is possible to significantly alleviate symptoms to improve both a patient’s physical functioning and quality of life5,6.

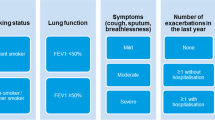

Optimal pharmacological therapy can optimize pulmonary function, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk of exacerbations5,7. However, many more traits can improve the health status of individuals with COPD, such as lifestyle aspects (smoking, physical activity), extra-pulmonary manifestations (skeletal muscle dysfunction, malnutrition) and psychosocial factors (coping style, anxiety and depression)8,9,10,11. These treatable traits (TTs) are commonly observed in different combinations10, they differ between sexes12, and are poorly predictable on the basis of the severity of the pulmonary function impairment10,13. Thus, they require individual comprehensive assessment14.

Given the frequent occurrence of multiple and coexisting TTs in an individual, interprofessional collaboration (IPC) where multiple healthcare providers (HCPs) provide care in parallel, can lead to better COPD patient outcomes15,16,17,18. An IPC is a team approach consisting of the patient, (potentially) their relatives, and HCPs from diverse disciplines, cooperating to comprehensively fulfil individual patient needs19. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest this results in lower health care costs20,21. The added value for patient outcomes of an IPC approach has also been demonstrated in chronic conditions other than COPD22,23,24.

Despite the demonstrated added value of IPC, for example in tertiary pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD15,16,17,18, this approach is currently underused in primary care25. Positive aspects of primary care are its financial accessibility, continuity of care, and topographical proximity to the patients, however other aspects like fragmentation of care and communication gaps result in its not fully meeting patient needs26,27,28. Many primary care COPD patients with multiple TTs would benefit greatly from alignment, support, coordination, and collaboration29.

Participatory action research (PAR) approach is a tried and tested approach to facilitate the development and implementation of a complex interventions such as IPC30,31. PAR is characterised by a bottom-up approach and a continuous process of action, observation, reflection, and planning cycles32,33,34. This dynamic and corrective approach is appropriate for complex interventions, and is therefore increasingly used in healthcare initiatives32. Co-creation is a PAR method, in which stakeholders collaboratively develop and implement an intervention, a new working method, or tackle an identified problem35. Co-creation increases the embedding of cultural, local, social constructs and uses existing skills, interests, and networks, to tailor the intervention to the target population32,33,35,36,37,38. Co-creation or equivalent methods have been shown to be successful in various contexts, including the primary care setting39,40, the COPD care setting41,42,43, among the elderly44,45 and associated HCPs46.

The aim of this study was to develop an IPC model for patients with COPD treated in primary care using a co-creation methodology.

Methods

Study design

We used PAR to develop an IPC model for application in the primary care COPD setting. The standard of Reporting Qualitative Research formed a guideline to include all items for comprehensive and explicit reporting47; see Supplementary File 1. Between September 2023 and January 2024, we held six co-creation sessions (CCS) in parallel in two independent regions of the Netherlands. The development process is shown in Fig. 1.

Regions

The model was developed in two Dutch regions, Nijmegen and Uden, where an integral comprehensive diagnostic assessment had been successfully implemented in secondary healthcare15. These regions are delineated to the extent of the affiliated general practitioners’ association. The Nijmegen region included 632 general practitioners (GPs) and more than 100 GP-practices, that work closely with two hospitals (one academic and one general hospital). The region is a more urban region, according to Dutch standards, with a total number of patients that receives GP-care of approximately 450.000. Most of these patients (±75%) lives in and around the city of Nijmegen. The Uden-region is smaller and more rural, according to Dutch Standards. The number of patients receiving primary GP-care is approximately 280.000. ±60% of these patients lives in one of the three small cities. The other 40% lives a smaller village or in the Dutch countryside outside these places. The region has 145 GPs, 62 affiliated GP-practices and one general hospital.

Both regions have GPs with an extended role (GPwER) for asthma and COPD. They have had advanced training in diagnosis and treatment of COPD and asthma, and provide training and quality assurance within their region. Moreover, the allied HCPs in both regions are united in networks within their own disciplines and meet several times a year. Although occasional meetings were organised where various disciplines meet, prior to our study no structured IPC for COPD had been implemented.

Assembling the co-creation teams

We set out to assemble two local co-creation teams with representatives from all the relevant stakeholders. Patients with COPD participating in the CCS were recruited via the Dutch lung foundation (Longfonds). HCPs were purposefully selected based on (i) known affinity or speciality in COPD care, (ii) knowledge and/or experience in IPC, (iii) mandate within their organisation, (iv) the local care structure, and v) the discipline they represent (i.e. only frequently involved disciplines were approached). The CCS were prepared and led by LdZ, and either EB or AvtH or both attended the CCS and took minutes.

When scheduling meetings, we considered travel distance for the stakeholders, the availability of a closed room to provide a productive and confidential environment, and a sufficient interval between meetings. Therefore, the meetings were planned in consultation with the participants in each region to maximize attendance.

Care development framework

The double diamond framework was used to structure the co-creation content. This framework is commonly used in product design settings, but other relevant studies note its functionality in care improvement or as a care development strategy48,49,50. The double diamond framework has four phases; discover, define, develop, and deliver. The framework assumes a process of first diverging and broadly identifying the problem(s) followed by narrowing, concretising, and prioritising them in the convergent phase. Any solution(s) for the defined problem(s) are also first divergent before becoming convergent. This framework suits an iterative process where (parts of) earlier phase(s) can be adjusted or sharpened. The content of each session was based on an a priori developed topic list and on the outcomes of the previous session(s). The topic list (see Box 1) emerged from discussions with experts and by scanning relevant literature. Creative work methods were used such as empathy mapping, making a journey map, and using a decision matrix51.

Developing the COPD IPC model

After each co-creation session, three researchers (LdZ, AvtH and EB) discussed and summarised the session outcomes. The minutes and interim versions of the model were sent to each participant to check, and they were asked to provide feedback. Based on this, the model was further developed.

Ethical statement

This review is part of a larger project (I-TEAM project), approved by Radboud University Medical Center Medical Ethics Review Committee (number 2023-16656). It is supported and partly funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) [project number 10270022120002].

Results

Assembling the co-creation teams

Stakeholders involved in the CCS are listed in Table 1. All HCPs met at least one of the purposeful sampling criteria. The number and type of HCPs involved in the CCS differed per region in line with differences in local care structure. The overall physical attendance rate of invited participants was 82%. In many cases, absent participants provided input via online meetings with the researchers in the following week.

CSS content

Table 2 gives a global overview of the CCS, with a more detailed description in Supplementary File 2. The methods are described in Fig. 1. All a priori determined topics were covered, and some were discussed multiple times.

Description of the co-creation process

During model development, several elements were identified as being noteworthy for the benefit of the anticipated implementation.

The sense of urgency among stakeholders was high several noting the need to improve primary COPD care; this was also reflected in the high attendance rate. To facilitate the co-creation process, they were very willing to provide current protocols and schedule additional face-to-face consultations with the researchers to provide extra information.

The patients judged their active participation as positive. They felt heard and could contribute relevant experiences. Moreover, patients contributed to an article in the national patient journal about their positive experience and their role as full-fledged discussion partners during the development process.

Extensive discussions were held on which HCP could best fulfil the role of care coordinator. Pragmatic reasons, such as flexibility, amount of time available, and lines of contact were mentioned as relevant factors.

A large overlap was reported regarding the perceived barriers for collaboration between both regions. For instance, the limited accessibility to relevant patient information for all HCPs, the limited knowledge about the potential contribution of other disciplines, limited time, and missing a coordinator were mentioned. Furthermore, similar discussions emerged in the two regions about the IPC target group. Should IPC be available only to those with a prior comprehensive assessment in secondary care, or should it be available also to those who lack this assessment and be referred directly by the GP? While the latter would significantly increase the number of eligible patients, the lack of a thorough assessment would negatively impact IPC quality and efficacy.

As a result of the great similarities in the perceived IPC success factors, only two differences in the final IPC model emerged between the two regions. Firstly, the initiation of IPC differed between the two regions. One region determined that IPC could only be initiated in the primary care setting, whereas the other concluded that IPC could be initiated in both primary and secondary care. This extra option was considered particularly beneficial for those patients at risk of becoming “stuck” between primary and secondary care. Referral to primary care HCPs could already be realised for them to start their treatment. Later, coordination of care could be transferred to the GP or practice nurse. This would prevent any avoidable waiting-times. Secondly, differences in the chosen communication platform between the two regions were noted. While one region preferred using a platform for safe communication between health care providers only, the other preferred using a communication platform in which the patient could also participate. Preferences were based on the platform already in use, their experiences with the platforms by the HCPs, and the possibility to include the patient.

The CCS participants stated they were willing to contribute to the implementation and dissemination of the IPC-approach and expressed their desire to remain informed and involved after the design phase. This underlined their commitment.

The final version of the model

The final version of the developed IPC model is presented in Fig. 2 and described in Table 3. A more detailed description per phase, including the degree of deviation from current care, can be found in Supplementary File 3. Although only the last two phases describe IPC in the COPD primary care setting, the importance of and dependency on the first three phases was underlined by the stakeholders, and they have therefore been included in the model.

Discussion

We developed an IPC model for primary care patients with COPD in cooperation with regional stakeholders. The development process: (i) was based on the current care system, (ii) was adjusted after practical input from HCPs and patients, and (iii) incorporated theoretical input from experts and scientific research. The PAR methodology, and more specifically the CCS approach, generated support among HCPs and their organisations in the region, in turn increasing the success rate32,33,34,52. Moreover, the stakeholders were extremely positive about the chosen co-creation approach, as substantiated in other research where a co-creation approach was used39,45,46,53.

The substantial overlap between the two regions, which were strictly separated, implies the generalisability and scalability of the model. The integrated care model we developed has the potential to be used more widely in other regions and several countries with a corresponding care model4. Though there are distinguishable components to the model that stand on their own, for the full operation of the model they will all need to be implemented. Furthermore, there is an opportunity for the strategy to be expanded on an international scale, as the model is in alignment with the core principles of good quality COPD care, as outlined by the IPCRG (i.e, classify the disease in a multidimensional way, use individualised self-management plan and communicate transparently with the patient)54.

We considered many facilitating preconditions of IPC in primary care or COPD care when developing the model to maximize the chance of its successful implementation. For example, we engaged patients in the development process, selected secure ICT-systems for communication purposes, applied it in a local context and added communication strategies and IPC team meetings on our topic list55,56,57,58. An important precondition that we were unable to meet, was remuneration for organising or attending the whole team meeting; remuneration is generally considered an important contributor to team functioning59,60. Other difficulties noted were integrating facilitating precondition at an organisational and system level, as has been reported in other interprofessional initiatives61,62,63. Meeting facilitating preconditions when developing the model does not guarantee a quick and successful implementation. Other studies show that on average, implementing a new way of working takes 17 years, and the success rate is only 20 percent64,65. Thus, to increase chances of a successful implementation, we applied multiple “lessons learned”, following Kilbourne et al.65,66. First, we used an overarching conceptual framework within the CCS, namely the double diamond, which supports iterative development processes. Second, a pilot is planned to evaluate the model’s feasibility, providing opportunities to implement improvements. And third, we involved implementation experts in the team to facilitate implementation.

Strengths and limitations

We employed a methodology well suited to the development of a complex intervention, and we onboarded stakeholders from all the relevant parties except for the health insurers. We anticipated that their involvement may potentially delay the process. To mitigate this potential disadvantage in determining IPC content, we remained close to current care structures for which payment from basic health insurance is available. Furthermore, we used digital forms of interprofessional communication in the IPC model and limited the use of meetings at which all HCPs relevant to an individual patient had to be concurrently available.

Involving patients was a major strength. Although due to their physical constraints and practical issues it was challenging to mobilise these patients. In future research we will try to recruit more patients to better guarantee their participation and therefore guarantee to recruit the patient perspective.

In addition, although the HCPs were actively involved in the (primary care) COPD setting, their input cannot be representative for all HCPs. However, due to their high levels of motivation, they are more willing to communicate the developed plan to their peers, one of the most effective implementation strategies.

To facilitate the model’s practical application, we chose to develop the IPC in two regions in which an interprofessional assessment had already been developed and implemented in the field of pulmonary care. This project matches these developments seamlessly and provides a missing piece of care for which many patients are potentially eligible.

Conclusion

We developed a model to improve IPC in primary COPD care by conducting six CCS in parallel in two regions. These sessions involved a committed group of patients with COPD and HCPs, under the direction of academic researchers. The development included a thorough mapping of the current COPD care and its associated barriers. The solutions were sought within collaboration and were benchmarked and ranked according to their impact and feasibility on care and collaboration.

The developed model was almost identical in both regions. This significant overlap suggests its generalisability, in turn indicating its potential for upscaling and transfer.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Pauwels, R. A. & Rabe, K. F. Burden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Lancet 364, 613–620 (2004).

Safiri, S. et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ 378, e069679 (2022).

Quaderi, S. A. & Hurst, J. R. The unmet global burden of COPD. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. 3, e4 (2018).

Kayyali, R. et al. COPD care delivery pathways in five European Union countries: mapping and health care professionals’ perceptions. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 11, 2831–2838 (2016).

Agustí, A. et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2023 report: GOLD executive summary. Eur. Respir. J. 61, 2300239 (2023).

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2024). https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/. Accessed March 2024.

Vestbo, J. et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 187, 347–365 (2013).

Agustí, A. et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 410 (2016).

Agustí, A. et al. Precision medicine in airway diseases: moving to clinical practice. Eur. Respir. J. 50, 1701655 (2017).

van ‘t Hul, A. J. et al. Treatable traits qualifying for nonpharmacological interventions in COPD patients upon first referral to a pulmonologist: the COPD sTRAITosphere. ERJ Open. Res. 6, 00438–02020 (2020).

McDonald, V. M. et al. Treatable traits: a new paradigm for 21st century management of chronic airway diseases: treatable traits down under international workshop report. Eur. Respir. J. 53, 1802058 (2019).

Souto-Miranda, S. et al. Differences in pulmonary and extra-pulmonary traits between women and men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Med. 11, 3680 (2022).

Miravitlles, M. & Ribera, A. Understanding the impact of symptoms on the burden of COPD. Respir. Res. 18, 67 (2017).

Koolen, E. H. et al. The COPDnet integrated care model. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 13, 2225–2235 (2018).

Koolen, E. H. et al. The clinical effectiveness of the COPDnet integrated care model. Respir. Med. 172, 106152 (2020).

Koff, P. B., Jones, R. H., Cashman, J. M., Voelkel, N. F. & Vandivier, R. W. Proactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 33, 1031–1038 (2009).

Poot, C. C. et al. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, Cd009437 (2021).

Kruis A. L., et al. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cd009437, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009437.pub2 (2013).

Gilbert, J. H., Yan, J. & Hoffman, S. J. A WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J. Allied Health 39, 196–197 (2010).

Trout, D., Bhansali, A. H., Riley, D. D., Peyerl, F. W. & Lee-Chiong, T. L. Jr A quality improvement initiative for COPD patients: a cost analysis. PLoS One. 15, e0235040 (2020).

Bandurska, E. et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of integrated care in management of advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 2879–2885 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Stokes, J., Anselmi, L., Bower, P. & Xu, J. Can integrated care interventions strengthen primary care and improve outcomes for patients with chronic diseases? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Res. Policy Syst. 23, 5 (2025).

Rizvi, F. et al. The Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland quality improvement project and integrated chronic kidney disease system: implementation within a primary care network. BMC Nephrol. 25, 255 (2024).

Martínez-González, N. A., Berchtold, P., Ullman, K., Busato, A. & Egger, M. Integrated care programmes for adults with chronic conditions: a meta-review. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 26, 561–570 (2014).

van Dongen, J. J. et al. Developing interprofessional care plans in chronic care: a scoping review. BMC Fam. Pract. 17, 137 (2016).

O’Malley, A. S. & Rich, E. C. Measuring comprehensiveness of primary care: challenges and opportunities. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 30, S568–S575 (2015).

Claessens, D. et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the Assessment of Burden of Chronic Conditions tool in Dutch primary care: a context analysis. BMJ Open. 15, e087197 (2025).

van Loenen, T. et al. Trends towards stronger primary care in three western European countries; 2006-2012. BMC Fam. Pract. 17, 59 (2016).

de Klein, M. M. et al. Comparing health status between patients with COPD in primary, secondary and tertiary care. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 39 (2020).

van der Veen, D. J. et al. The regional development and implementation of home-based stroke rehabilitation using participatory action research. Disabil. Rehabilitation. 47, 2899–2913 (2025).

Kari, H., Kortejärvi, H. & Laaksonen, R. Developing an interprofessional people-centred care model for home-living older people with multimorbidities in a primary care health centre: A community-based study. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 5, 100114 (2022).

Baum, F., MacDougall, C. & Smith, D. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 60, 854–857 (2006).

Hills, M., Mullett, J. & Carroll, S. Community-based participatory action research: transforming multidisciplinary practice in primary health care. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 21, 125–135 (2007).

Elliott, R. A. et al. Development of a clinical pharmacy model within an Australian home nursing service using co-creation and participatory action research: the Visiting Pharmacist (ViP) study. BMJ Open. 7, e018722 (2017).

Leask, C. F. et al. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res. Involv. Engagem. 5, 2 (2019).

Langford, R. et al. Co-designing adult weight management services: a qualitative study exploring barriers, facilitators, and considerations for future commissioning. BMC Public. Health 24, 778 (2024).

Halvorsrud, K. et al. Identifying evidence of effectiveness in the co-creation of research: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the international healthcare literature. J. Public. Health 43, 197–208 (2021).

Kindon, S., Pain, R., & Kesby, M. in International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (eds Kitchin, R., & Thrift, N. (Elsevier, 2009).

Hartney, E., Barnard, D. K. & Richman, J. Development of best practice guidelines for primary care to support patients who use substances. J. Prim. Care Community Health 11, 2150132720963656 (2020).

Albitres-Flores, L. et al. Co-creation process of an intervention to implement a multiparameter point-of-care testing device in a primary healthcare setting for non-communicable diseases in Peru. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24, 401 (2024).

An, Q. et al. A scoping review of co-creation practice in the development of non-pharmacological interventions for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a health CASCADE study. Respir. Med. 211, 107193 (2023).

Lundell, S., Toots, A., Sönnerfors, P., Halvarsson, A. & Wadell, K. Participatory methods in a digital setting: experiences from the co-creation of an eHealth tool for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 22, 68 (2022).

Barker, R. E. et al. Integrating home-based exercise training with a hospital at home service for patients hospitalised with acute exacerbations of COPD: developing the model using accelerated experience-based co-design. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 16, 1035–1049 (2021).

Mansson, L., Wiklund, M., Öhberg, F., Danielsson, K. & Sandlund, M. Co-creation with older adults to improve user-experience of a smartphone self-test application to assess balance function. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 17, 3768 (2020).

Leask, C. F., Sandlund, M., Skelton, D. A. & Chastin, S. F. Co-creating a tailored public health intervention to reduce older adults’ sedentary behaviour. Health Educ. J. 76, 595–608 (2017).

Braithwaite Stuart, L., Elliott, N., Hanmer, R. & Woodhead, A. Meaningful co-production to bring meaningful change: developing the allied health professionals dementia framework for Wales together. Dementia 23, 724–740 (2024).

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A. & Cook, D. A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 89, 1245–1251 (2014).

Clune, S. J. & Lockrey, S. Developing environmental sustainability strategies, the Double Diamond method of LCA and design thinking: a case study from aged care. J. Clean. Prod. 85, 67–82 (2014).

Design Council. Eleven lessons. A study of the design process (2005). www.designcouncil.org.uk. [cited 2025 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/.

Dalton, L. M. et al. The Allied Health Expansion Program: Rethinking how to prepare a workforce to enable improved public health outcomes. Front. Public. Health 11, 1119726 (2023).

van ’t Veer, J., Wouters, E. J., Veegers, M., & Lugt van der, R. Ontwerpen voor zorg en welzijn (Coutinho, 2020).

Benfante, A., Messina, R., Milazzo, V. & Scichilone, N. How to unveil chronic respiratory diseases in clinical practice? A model of alliance between general practitioners and pulmonologists. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 44, 106–110 (2017).

Lundell, S. et al. Building COPD care on shaky ground: a mixed methods study from Swedish primary care professional perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 467 (2017).

IPCRG. What Does Good Quality COPD Care Look Like? (International Primary Care Respiratory Group, 2023).

Sibbald, S. L., Ziegler, B. R., Maskell, R. & Schouten, K. Implementation of interprofessional team-based care: a cross-case analysis. J. Interprof. Care. 35, 654–661 (2021).

Montano, A. R., Cornell, P. Y. & Gravenstein, S. Barriers and facilitators to interprofessional collaborative practice for community-dwelling older adults: an integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 32, 1534–1548 (2023).

Paciocco, S., Kothari, A., Licskai, C. J., Ferrone, M. & Sibbald, S. L. Evaluating the implementation of a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management program using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: a case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 717 (2021).

Peer, Y. & Koren, A. Facilitators and barriers for implementing the integrated behavioural health care model in the USA: an integrative review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 31, 1300–1314 (2022).

Wranik, W. D. et al. Funding and remuneration of interdisciplinary primary care teams in Canada: a conceptual framework and application. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 351 (2017).

McDonald, J., Powell Davies, G., Jayasuriya, R. & Fort Harris, M. Collaboration across private and public sector primary health care services: benefits, costs and policy implications. J. Interprof. Care. 25, 258–264 (2011).

Oostra, D. L., Harmsen, A., Nieuwboer, M. S., Rikkert, M. & Perry, M. Care integration in primary dementia care networks: a longitudinal mixed-methods study. Int. J. Integr. Care. 21, 29 (2021).

Nancarrow, S. A. et al. Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work. Hum. Resour. Health 11, 19 (2013).

Doornebosch, A. J., Smaling, H. J. A. & Achterberg, W. P. Interprofessional collaboration in long-term care and rehabilitation: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23, 764–77.e2 (2022).

Rubin, R. It takes an average of 17 years for evidence to change practice-the burgeoning field of implementation science seeks to speed things up. JAMA 329, 1333–1336 (2023).

Kilbourne, A. M., Glasgow, R. E. & Chambers, D. A. What can implementation science do for you? key success stories from the field. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 783–787 (2020).

Genootschap, N. H. NHG-Standaard COPD (M26). (Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, 2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants involved in the co-creation sessions, especially the healthcare providers who actively considered which stakeholders had to be present, as well as Het Longfonds who arranged contacts with the patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LdZ, AvtH, EB prepared and led the CCS project. LdZ conceptualised the model with input from AvtH, EB, BvdB, MdM. The other authors (LvdB, MvdH, MS) contributed to the drafting, review and editing of the paper. All authors read, commented on, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.v.d.H. reports participating in the advisory board, lecturing, or receiving grants from the following parties: Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Lilly, Merck, MSD, Novartis, NVALT, Pamgene, Pfizer, Roche diagnostics, Roche Genentech, Sanofi, Stichting Treatmeds, and Takeda. All payments were made to the institution, and fall outside the scope of the submitted work. B.v.d.B. reports consultation, presentation, and travel fees/support by AstraZeneca B.V., Chiesi Pharmaceuticals B.V., Sanofi B.V., Boehringer Ingelheim bv, and Genzyme Europe B.V. All payments were made directly to the institution, and all fall outside the scope of the submitted work. M.A.S. reports receiving grants from Lung Foundation Netherlands, Stichting Astma Bestrijding, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, TEVA, Chiesi, Sanofi, and fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, TEVA, GSK and Chiesi, all falling outside the scope of the submitted work. All payments were made to M.A.S.’s employer. M.A.S. is founder of Care2Know B.V. All other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Zwart, F., van den Bemt, L., van den Borst, B. et al. Developing an interprofessional collaboration for COPD patients in primary care: a participatory action research approach. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 43 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00437-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00437-7