Abstract

In this work, we investigate discrete-time transport in a generic U(1)-symmetric disordered model tuned across an array of different dynamical regimes. We develop an aggregate quantity, a circular statistical moment, which is a simple function of the magnetization profile and which elegantly captures transport properties of the system. From this quantity, we extract transport exponents, revealing behaviors across the phase diagram consistent with localized, diffusive, and—most interestingly for a disordered system—superdiffusive regimes. Investigation of this superdiffusive regime reveals the existence of a prethermal “swappy” regime unique to discrete-time systems in which excitations propagate coherently; even in the presence of strong disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of large-scale, high-fidelity, tunable, and accessible digital quantum devices is revolutionizing modern quantum physics. Notable advances include the implementation of large-scale quantum algorithms, the simulation (via e.g., the Suzuki–Trotter expansion1,2) of continuous-time models on actual hardware3,4,5,6,7,8, diagonalization algorithms9,10, and the analysis of transport properties11,12,13,14.

However, these advances have also resulted in an emerging reconceptualization of large circuits as realizing digital phases of matter in their own right. Notable examples include: discrete time crystals15,16, measurement-induced phase transitions17,18,19, many body scars20,21, Hilbert space fragmentation22,23,24, and cellular automata25. Essentially, despite their fundamental differences, a sufficiently large discrete-time system exhibits emergent phenomena in a manner consistent with continuous phases of matter. This deterritorialization of phase, now encompassing digital systems, yields questions of immediate interest and relevance: how can one probe phase transitions and information-spreading in digital matter? As digital systems do not conserve energy, but can sustain other conserved quantities, what are the transport features of such systems? Are there additional regimes and features unique to digital phases of matter, absent in their continuous-time counterparts?

In this work, we seek to address some of these questions by constructing a generic gate-based, disordered, U(1)-symmetric model; inspired by the more recent development of a discrete-time version of the XXZ spin chain 26,27,28. The continuous-time XXZ model, and its isotropic counterpart, the Heisenberg model, were conceived as purely theoretical constructs29, but have become standard tools for investigating transport properties30,31,32 and many-body localization (MBL)33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Meanwhile, the transport properties of its discrete-time counterpart remain only partially mapped out.

Our model can be tuned across a two-dimensional phase space to exhibit both integrable and non-integrable regimes, and a range of emergent phenomena. This includes a crossover between ergodic and localized regimes44,45,46,47, and a line along which all gates in our model are dual-unitary (DU)48,49. These DU gates are endowed with an additional U(1) symmetry, and thus become generalized SWAP gates (see Sec. “Overview of regimes of transport dynamics”).

We leverage our model into an investigation of the static properties of our model, revealing no unexpected behavior. However, we subsequently interrogate transport in our model and identify a prethermal regime that is a priori unique to discrete-time systems. In the vicinity of the DU line, excitations propagate faster than in the ergodic phase, leading to transient, coherent information transfer over short timescales, the “swappy” regime. This regime is intrinsically Floquet in origin: it arises from the finite, non-scaled unitary kicks that define the discrete-time dynamics, and therefore disappears in the continuous-time (Trotterized) limit where the kick amplitude is taken to zero. In this sense, the swappy regime has no analog in continuous-time XXZ models and reflects a genuinely discrete-time transport phenomenon.

Finally, by deploying circular moments related to wrapped probability distributions, we develop an aggregate quantity, R, which captures the features of many-body transport in a concise way. As this quantity is singularly composed of local Z-basis expectation values, it is highly amenable to experimental implementation; paving the way for the near-future experimental analysis of transport in digital matter.

In Sec. “Model”, we present our model and compare it with similar ones. Sec. “Overview of regimes of transport dynamics” outlines the primary features anticipated to appear in our phase diagram, as suggested by the existing literature. Sec. “Analysis of the results” reports the results: for static properties obtained via exact diagonalization and for dynamical properties that define the finite time and size transport analysis of our model.

Results

Model

We consider a system of N qubits undergoing discrete-time evolution under the repeated application of a Floquet unitary \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\). The Floquet unitary is decomposed as a product of N nearest-neighbor gates \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}={\prod }_{\{P(n)\}}{\widehat{U}}_{n,n+1}\), ordered according to a random permutation P of the set of all site indices n (illustrated in Fig. 1c). We assume periodic boundary conditions. The two-qubit gates have the form:

which is composed of the single-qubit rotations \({e}^{-i{h}_{n}{\hat{S}}_{n}^{z}}{e}^{-i{{h}^{{\prime} }}_{n}{\hat{S}}_{n+1}^{z}}\) and a nearest-neighbor XXZ-like interaction generated by the Hamiltonian:

with the Peierls phase ϕn50. Here, the operators \({\hat{S}}_{n}^{\alpha }\) for α ∈ {x, y, z} are the standard spin-1/2 operators acting locally on the n-th site, and the raising and lowering operators are defined as \({\widehat{S}}_{n}^{\pm }={\widehat{S}}_{n}^{x}\pm i{\widehat{S}}_{n}^{y}\), respectively. The two-qubit gate in (1), with five parameters \(\{{h}_{n},{{h}^{{\prime} }}_{n},{\phi }_{n},J,{J}_{z}\}\), can, in fact, describe any two-qubit gate that conserves the total magnetization \(\widehat{M}={\sum }_{n}{\widehat{S}}_{n}^{z}\) in the z-direction. Since each individual gate conserves the magnetization, the global Floquet unitary also conserves the total magnetization \([\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}},\widehat{M}]=0\), which is an essential prerequisite to define the transport of spin excitations.

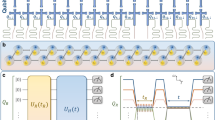

Schematics showing a different regimes of our generic U(1)-symmetric model. Along the three solid borders the model is integrable; whilst the dashed border at Jz = π spans four distinct regimes, and is the region we predominantly address in this article. b shows the initial (dotted) and late-time (solid) spin magnetization profiles for different phases along the Jz = π line. c shows discrete time evolution as determined by a (periodic) U(1)-symmetric Floquet unitary \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\) comprised of nearest-neighbor gates.

For each two-qubit gate \({\widehat{U}}_{n,n+1}\), we sample the three phase parameters \(\{{h}_{n},{{h}^{{\prime} }}_{n},{\phi }_{n}\}\) randomly from the uniform distribution on the interval [−π, π]. This introduces disorder to our circuit model. The two remaining parameters J and Jz, however, are fixed across all gates in a given Floquet unitary. Tuning J and Jz allows us to explore various regimes of transport in our model. Observing that the two-qubit gate \({\widehat{U}}_{n,n+1}\) is 2π-periodic in both J and Jz we can restrict our parameter space through patterning (reflection and tessellation) to the region J, Jz ∈ [0, π], shown in Fig. 1a.

Similar discrete-time models have appeared in recent literature47,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. Notably, refs. 47,57,58,59 use U(1) symmetric models but with a brickwork geometry. Our random gate ordering is more similar to the approach in ref. 53. This approach also allows systems with odd and even site numbers, N, to be treated equivalently and avoids issues related to the slower thermalization of brickwork circuits, as discussed in ref. 59. A more in-depth analysis of gate permutations is presented in Sec. S1 of the Supplementary Materials (SM). Finally, we note that our model is well-suited to for realization on currently available quantum hardware. A different gate decomposition of \({\widehat{U}}_{n,n+1}\), which may be more suitable for implementation on quantum simulators, is discussed in Sec. S2.

Overview of regimes of transport dynamics

Before presenting our numerical results, in this section, we give an overview of the expected different regimes of dynamics in our model. First, we identify three solvable regimes of our model, corresponding to three solid borders of the J, Jz ∈ [0, π] square in Fig. 1a:

-

If Jz = 0 the Floquet unitary is integrable, since it can be mapped to a quadratic fermion model by a Jordan–Wigner transformation.

-

If J = 0 the Floquet unitary reduces to an Ising model in a disordered longitudinal magnetic field, since it is completely diagonal in the \({\widehat{S}}_{n}^{z}\) basis of each spin.

-

If J = π each gate of our model is DU. In what follows we show that imposing U(1) symmetry to DU gates leads to generalized SWAP gates making the system effectively non-interacting and therefore integrable.

In the first of these regimes, along the free-fermion line Jz = 0, we expect transport to be suppressed by Anderson localization, as a result of the disorder fields \(\{{h}_{n},{{h}^{{\prime} }}_{n},{\phi }_{n}\}\). Similarly, in the second of the exactly solvable regimes, along the Ising line, there is no transport of spin-z excitations since, at J = 0, not only is the total magnetization \(\widehat{M}\) conserved, but also the local magnetization \({\widehat{S}}_{n}^{z}\) for every spin n is conserved.

We now turn our attention to the third of our exactly solvable regimes, at J = π, where the two-qubit gate can be decomposed as:

for \({\kappa }_{\pm }=\mp (h+{h}^{{\prime} })/2+{J}_{z}/4\) and \({\xi }_{\pm }=\pi \pm (h-{h}^{{\prime} })/2-{J}_{z}/4\mp \phi\). We see that, along this line in parameter space, our two-qubit gate becomes a SWAP gate that also imprints a phase on the swapped particles. We will refer to this gate as a generalized SWAP and to the \((J,J_z)=(\pi,\pi)\) point as the “SWAP point”. This use of the term is justified within the context of the Weyl chamber, where gates connected by local rotations are defined as equivalent54,60. Hence, we do not expect the system to thermalize along the DU line, as any spin excitation propagates through the circuit unimpeded via a series of these generalized SWAP gates. The intrinsic behavior of this type of gate ensures that any DU circuit preserving U(1) symmetry is integrable, regardless of connectivity.

The non-thermalizing behavior along these three borders raises several interesting questions about the dynamics if we vary slightly away from them. Traditionally, this has been studied in the proximity of the Ising line. Even if we perturb away from it, by increasing J to small but non-zero values, spin transport is still suppressed, since the kinetic energy J-term in (2) is dominated by the disorder fields \(\{{h}_{n},{{h}^{{\prime} }}_{n},{\phi }_{n}\}\). This is roughly analogous to MBL in continuous-time models35,61, but, as MBL is not the main focus of this article, we do not interrogate the stability of this regime in the thermodynamic limit. However, one can wonder if something similar can arise around the DU line. Will the system thermalize near it? Is there an extended regime of anomalous transport dynamics near the DU line? These are some of the key motivating questions of our work. We will show below that indeed there is a distinctive regime of anomalous transport proximate to the DU line, which we will call the “swappy” regime. Moving further away from the three solvable sides of our J, Jz ∈ [0, π] square, we enter the ergodic regime. Here, we expect transport of spin excitations to lead to rapid thermalization of the system. To explore the behavior of our model between the Ising and the DU line, we focus on the Jz = π line, since it is maximally distant (in (J, Jz) parameter space) from the integrable free-fermion line, and exhibits a wide array of interesting behaviors as a function of the single parameter J. In particular, throughout this work we focus on four points representative of the different regimes along this line: localized at J = 0.395 (represented by the symbol •), ergodic at J = 1.374 (represented by), swappy at J = 2.551 (represented by ▪), and near-SWAP at J = 3.138 (represented by ⋆). These regimes are shown schematically in Fig. 1b. These regimes exhibit different kinds of emergent transport, and, as we flexibly refer to regimes and types of transport throughout this work, it is instructive to preemptively summarize our findings here. We find either complete localization or sub-diffusive behavior in the localized regime, diffusive behavior in the ergodic regime, and super-diffusive behavior in the swappy and near-SWAP regime. This super-diffusive behavior is augmented by ballistic propagation of individual excitations in the swappy and near-SWAP regimes. These results are shown in Figs. 5 and 6, and discussed in Sec. “Analysis of the results”.

We emphasize that a full scaling analysis of the localized regime falls outside the scope of this work, and due to analogous literature surrounding the stability of continuous-time MBL, we expect this question to be intractable given current numerical and experimental capabilities61,62. We can thus only claim to find phenomenological signatures of localization in this work: i.e., a total breakdown of transport, or the sub-diffusive (and/or logarithmic) spreading of information. These phenomenological signatures may be prethermal effects, or finite-size effects, or both; we defer a more detailed investigation of the stability of localization in discrete-time systems to future study. In this work, we focus on phenomenological signatures of transport throughout the phase diagram, at intermediate system sizes N ≤ 22, and exponential timescales; with an additional focus on interrogating the nature and stability of the swappy regime.

Analysis of the results

Our goal in this paper is to understand the various equilibrium and dynamical regimes in our U(1)-symmetric circuit model, outlined in the previous section. To characterize our model, we take two complementary approaches: we compute static spectral properties and dynamical properties. These two approaches are complementary, since they reveal different aspects of the model, as described below.

One way to characterize our model is by means of its spectral properties, i.e., properties relating to the eigenphases and eigenvectors of the Floquet unitary, \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\left|{\varphi }_{i}\right\rangle ={e}^{-i{\varphi }_{i}}\left|{\varphi }_{i}\right\rangle\). Specifically, we study the mean eigenstate entanglement entropy and the mean eigenvalue gap ratio–both indicators of quantum chaos61. Both these quantities require partial diagonalization of \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\), which we perform using the POLFED method63, technical details are given in Sec. “POLFED” of the SM. We briefly discuss the relevance of these quantities to the analysis of the ergodicity of a system in Sec. “Equilibrium diagnostics and their interpretation” of the SM.

First, consider a bipartition of the system into subsystems A and B. The entanglement entropy of a Floquet eigenstate \(\left|{\varphi }_{i}\right\rangle\) is given by:

where \({\widehat{\rho }}_{i}^{A}=T{r}_{B}[\left|{\varphi }_{i}\right\rangle \left\langle {\varphi }_{i}\right|]\) is the reduced density matrix for subsystem A. Averaging si over eigenstates in a fixed magnetization sector M (see Sec. “Methods” of the SM) and across different Floquet unitaries yields the mean entanglement entropy 〈s〉. For an ergodic system, we expect the eigenstates to have an average entanglement entropy similar to a typical random state in the magnetization sector, i.e., close to the Page entropy64.

Specifically, as our numerics are performed in a fixed total magnetization sector M = 0, the natural random-state benchmark is the Page value restricted to that charge sector. The exact finite-size expression has been derived by Bianchi and Donà in ref. 65,

with \({d}_{{N}_{A}}=\dim {{\mathcal{H}}}_{A}^{({N}_{A})}\) (\({d}_{{N}_{A}}=\left(\begin{array}{c}{L}_{A}\\ {N}_{A}\end{array}\right)\)), \({d}_{{N}_{B}}=\dim \,{{\mathcal{H}}}_{B}^{(M-{N}_{A})}\), \(D={\sum }_{A}{d}_{{N}_{A}}{d}_{{N}_{B}}\) and \({\bar{\lambda }}_{{N}_{A}}={d}_{{N}_{A}}{d}_{{N}_{B}}/D\). We therefore normalize the mean eigenstate entropies by this fixed-magnetization Page value when assessing Page-like saturation in the ergodic regime.

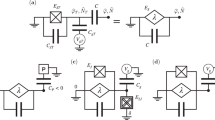

For this reason, it is convenient to normalize the average entropy by the Page entropy, 〈s〉/sPage. In Sec. “Efficient computation of the entropy in a magnetization subsector” of the SM, we discuss how to compute the entanglement entropy of the eigenstates efficiently. In Fig. 2a we see that, for our model, the mean entanglement entropy varies from a small value in the localized regime (J ≪ π) to the Page entropy in the ergodic regime. This is consistent with the conclusion that—at least for our finite-N—the system fails to thermalize in the long-time limit in the localized regime, but thermalizes in the ergodic regime. Figure 2a also appears to show deviations from the Page entropy as we approach the SWAP point J → π. However, we observe that as the system size N increases, the range of J values around π associated with lower entanglement entropy contracts. We attribute this instability to the emergence of (near-)conserved operators as the Floquet gates approach the DU line. These operators produce near-invariant subspaces and thus effectively split the spectrum into overlapping subspectra. When raw spectral measures are computed without first resolving those (approximate) symmetry sectors, the resulting level-spacing statistics and entanglement values can be distorted66. We comment on this in Sec. S3 of the SM.

a shows results for the averaged von Neumann entanglement entropy normalized by the Page value of ref. 65, along the Jz = π line and for various system sizes. Error bars represent standard deviations over at least 40 disorder realizations, selected with a 3.5× Interquartile Range86. Residual large fluctuations near the SWAP point arise from near-degeneracies in the Floquet spectrum. Panel b displays the phase diagram for the gap ratio obtained for N = 15 with values averaged over 10−20 trajectories. Results obtained with the POLFED eigensolver in fixed-M = 0 sector63 (see Sec. “POLFED” for numerical details).

Our next quantifier is the mean gap ratio. For each Floquet eigenphase φi, the ratio of consecutive gaps is defined as:

where δφi = φi+1 − φi is the gap between consecutive eigenphases within the same magnetization sector67. We compute the mean gap ratio 〈r〉 by averaging ri over all computed eigenphases in a sector and over many Floquet unitaries. In the absence of time-reversal symmetry, the model is expected to yield 〈r〉 ≈ rCUE = 0.6027 if the system is ergodic, or 〈r〉 ≈ rPoi = 0.3863 if the system is integrable66. Figure 2b shows the transition between the localized regime for small J and the ergodic regime for sufficiently large J. It also shows a deviation from the ergodic value when Jz = 0, corresponding to our model being integrable (mappable to free fermions), as well as on the dual-unitary line J = π.

Both the mean entanglement entropy and the mean gap ratio probe equilibrium properties of the model in the infinite-time limit. These two diagnostics probe complementary aspects of the long-time state. The mean eigenstate entanglement entropy tests whether typical energy eigenstates have thermal reduced states (as expected if the Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis, ETH, holds), while the mean gap ratio diagnoses spectral correlations: Wigner-Dyson statistics imply level repulsion and RMT-like eigenvectors, whereas Poisson statistics imply level clustering. Together, therefore, they indicate whether the system’s infinite-time (thermal) behavior is consistent with ergodicity or with nonthermal dynamics.

So, even if the system ultimately thermalizes, interesting intermediate-time behaviors may arise that will not be detected by these spectral quantities. Next, we turn to the quantification of the transport properties of the model, which can reveal distinct dynamical regimes at intermediate times.

We remark that the crossing point extracted from the mean adjacent gap-ratio and from the rescaled eigenstate entanglement exhibits a modest, systematic shift as L is increased for the range of sizes accessible to our numerics. Such finite-size drifts are routinely observed in ED studies of disordered interacting chains and were historically used as an operational probe of the putative MBL transition68. However, more recent analyses emphasize that these finite-size signatures are difficult to extrapolate to the thermodynamic limit: rare thermal regions and avalanche-type instabilities can produce apparent localization at small sizes, which is destroyed upon increasing scale69,70, and large-scale numerics and reviews discuss slow crossovers and sample-to-sample fluctuations that complicate direct interpretation71,72. Accordingly, while our data for accessible L are consistent with a crossover from ergodic to strongly suppressed transport regimes, they do not constitute proof of a stable MBL phase in the thermodynamic limit; we therefore limit our claims to the finite-system behavior reported here.

We first present the raw numerical data for the evolution of the local magnetization profile, starting from a non-equilibrium initial state consisting of a localized spin excitation in a homogeneous spin background. Suitably quantifying the spread of the initially localized excitation should encapsulate the transport properties of the system. However, we find that the local magnetization profile is inconvenient for extracting transport coefficients. Then, we map the local magnetization profile to a quasi-probability distribution. Using the wrapped normal distribution as a helpful reference model, we use the quasi-probability distribution to extract transport coefficients. We therefore discuss these transport coefficients, and finally, we conduct a scaling analysis of the transport properties. This study reveals an intermediate-time prethermal “swappy” regime, unique to digital systems, where information propagates coherently and ballistically, even in a strongly disordered setting. We discuss heuristic mechanisms underlying this regime, and its stability, in Sec. “Analysis of the results”.

The central object used to explore dynamics in our model is the local spin magnetization profile

We exploit initial states of the form

where \({\widehat{P}}_{M}\) is a projector onto the subspace of total magnetization M = ∑nMn. In numerical practice, to avoid working with the density matrix \(\widehat{\rho }(0)\) in (7), we choose the initial pure state \(\widehat{\rho }(0) \sim {\widehat{P}}_{N/2}^{\uparrow }\left|{\psi }_{{\rm{rand}}}^{(M)}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{{\rm{rand}}}^{(M)}\right|{\widehat{P}}_{N/2}^{\uparrow }\) where \(\left|{\psi }_{{\rm{rand}}}^{(M)}\right\rangle\) is a random state in the subspace of fixed total magnetization M, and \({\widehat{P}}_{N/2}^{\uparrow }\) is the projector onto the excited state of the middle spin. This is numerically more efficient, since we only need to operate on the pure state instead of on the density matrix. In Sec. S6A of the SM, we show in detail that this is equivalent to choosing an initial maximally-mixed state in (7), up to some negligible random fluctuations. Notably, one can directly connect the quantity of (7) computed in a given magnetization subsector with high-temperature correlation functions, as is shown in detail in Sec. S6 of the SM.

For this choice of initial state, the central spin is fully polarized such that MN/2(0) = 1/2. The excess magnetization M − 1/2, where M = ∑nMn(t), is distributed evenly over all other spins Mn≠N/2(0) ≈ MB = (M − 1/2)/(N − 1). In other words, the initial local magnetization is in the non-equilibrium configuration:

As total magnetization M is conserved in our model, and as thermalization would result in the initially localized spin excitation spreading through the system, full thermalization corresponds to the total magnetization M being uniformly distributed across all spins Mn(t → ∞) ≈ M/N. As is standard, we focus on the largest subsector: taking M = 0 from this point onward.

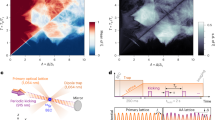

We present our numerical results for the magnetization profile Mn(t) for a system of N = 20 particles in Fig. 3 at the four key points along the Jz = π line (as shown in Fig. 1a). The top panels a-d illustrate the dynamics for a typical individual realization of \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\), while the bottom panels e-h show the dynamics of the local magnetization averaged over many different realizations of the Floquet unitary.

Results of numerical propagation of the initial spin inhomogeneity in the M = 0 sector under U(1)-symmetric Floquet dynamics at N = 20. a–d show typical results for single realizations of the initial state and Floquet unitary within the localized regime, ergodic regime, and two points in the swappy regime, respectively. e–h show results in the respective regimes after averaging over 100 realizations. Horizontal lines indicate the time taken to complete a single Floquet cycle (solid), N/2 (dashed), and the time after which we calculate results stroboscopically (dotted). Although the light cones in (b, f) visually show the excitation spreading and an apparent equilibration for t between \({\mathcal{O}}(N)\) and \({\mathcal{O}}({N}^{2})\), we confirm diffusive transport quantitatively in the following sections. An analysis of what happens exactly on the light-cone is offered in Sec. S3 of the SM.

As outlined in Sec. “Model”, and depicted in Fig. 1c, time evolution is carried out by repeated application of the Floquet unitary \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\). We evaluate each of the first t = 100 time steps, but to reach later times we apply clusters of Floquet unitaries together \({\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}}^{k}\), which effectively realizes a stroboscopic dynamics with a longer period after t > 100. This stroboscopic approach leads to an apparent preservation of excitation on some particular sites, however, even at this later times, we expect the excitation to move continuously along the chain. Throughout Fig. 3, horizontal lines mark (solid) t = 1, the application of the first whole \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\), (dashed) t = N/2 = 10, the time for ballistic excitations to reach the system boundary, and (dotted) t = (N/2)2 = 100, the time taken for a particle on site N/2 to diffuse to the boundary of the system. These three benchmarks help compare different types of transport, where the t = 100 line serves as a reference for identifying diffusive or anomalous behavior. These benchmarks are heuristic guides for distinguishing ballistic, diffusive and anomalous transport. We make these statements quantitative below via fits of a series of different quantities we extract from the evolution of the magnetization profile of the system. White regions denote homogenized Mn(t) = 0, indicating regions in which the state realizes a local identity and has self-thermalized.

In the localized regime (•), shown in a and e, the initial spin excitation remains localized for a long-term, preserving its general shape and position in the spin chain. The system exhibits self-averaging at late times (i.e., after the early-time relaxation dynamics), consistent with many-body localization studies35,71,73,74. Self-averaging means a system’s properties become stable and predictable in large samples without many different realizations. This feature breaks down in phase transitions where disorder causes persistent fluctuations across regions, preventing uniform behavior. The initial excitation spread slowly, likely logarithmically, in line with what is usually marked as localized behavior61,62,74,75.

In the ergodic regime (▸), shown in b and f, diffusive transport is qualitatively evidenced by the excitation reaching the boundary, and the subsequent onset of thermalization, at time t = 100 (the dotted black line). Also at this point, self-averaging occurs, with individual realizations b resembling the averaged behavior f.

The swappy regime (■) is displayed in panels c and g. The individual realization in panel c demonstrates a clear leftward propagation of the initial excitation, with the direction determined randomly by the permutation P of the local gates making up the Floquet unitary. Initially, before the small deviations from the SWAP gate become evident, the excitation propagates coherently and ballistically through the system, moving a fixed number of sites per Floquet cycle. We will later quantify this behavior using the instantaneous speed parameter \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }\) in Sec. “Analysis of the results”. These ballistic excitations eventually decohere, leading to thermalization after roughly 10 Floquet applications. This fast thermalization is more apparent in the averaged dynamics of panel g, where excitations propagate in both directions, splitting into “twin peaks.” These excitations self-interact and thermalize rapidly after t ~ 10. This finding is significant: thermalization occurs on a timescale consistent with ballistic transport in a disordered quantum system. Such anomalous transport has been observed in disorder-less models (see refs. 26,27,28), but here we find counter-intuitive evidence of such behavior in strongly disordered systems.

Near the SWAP point (⋆), panel d clearly shows the leftward propagation of the initial excitation. However, in this case, the system continues to exhibit a near-perfect exchange of spin excitations with neighboring sites, even at late times. Panel h appears to show thermalization at late times. However, this is actually the result of averaging out the peak, caused by small variations in the underlying propagation speeds. Essentially, while the center of Mn(t) shifts, its initial delta-peaked functional form remains unchanged. Averaging many such randomly centered delta-peaked distributions creates the appearance of thermalization at late times. Once again, we observe an early-time “twin peaks” structure, where the excitation propagates coherently and ballistically in both directions. Unlike in most of the swappy regime, the twin peaks here are well-resolved. The absence of full thermalization at the near-SWAP point is likely due to the timescales accessed; with a complete failure to thermalize at all times associated only with the SWAP point J = π.

To gain a deeper understanding of the transport dynamics of the initially localized excitation: we first construct a statistical moment derived from the magnetization profile. From this moment, we can extract transport properties (namely transport exponents and drift) which can in turn be related (via an appropriate choice of initial state) to high-temperature correlation functions (see Sec. S6 of the SM).

To this end, we first construct a quasi-probability distribution pn(t) by transforming the magnetization profile Mn(t) as follows:

This transformation approximately maps the initial background magnetization values to zero, pn≠N/2(0) ≈ 0, with the excitation at pN/2(t) = 1, and satisfies Kolmogorov’s second probability axiom, ∑npn(t) = 1, due to the U(1) symmetry (i.e., conservation of M). Small fluctuations during the random initial state preparation may cause Mn(t) < MB, leading pn≠N/2(0) to dip below zero. As a result, pn(t) technically becomes a quasi-probability distribution, violating Kolmogorov’s first axiom. However, this effect is minimal and vanishes as N → ∞. We observe no pathological behavior due to these small negative values, so we treat pn(t) as a valid probability distribution. Full thermalization, Mn(t → ∞) = M/N, results in a uniform distribution, pn(t → ∞) ≈ 1/N.

Since we assume periodic boundary conditions for our model, it is also convenient to introduce the circular mean; defined by the complex number:

where \(\theta_n = \frac{2\pi}{N}\left(n-\frac{N}{2}\right)\in[-\pi,\pi)\) maps the magnetization profile, via the quasi-probability distribution pn(t), of N spins to a single complex value within the unit circle ∣R(t)∣≤1. Here, the parameters:

quantify the position and the spread of the spin excitation, respectively. To see this intuitively, consider the example of a quasi-probability profile pn = δn,m for a spin excitation localized at site n = m. It corresponds to the point \(R={e}^{i{\theta }_{m}}\) on the unit circle, with the argument μ = θm reflecting the position m of the excitation and spread parameter σ = 0 indicating that the excitation is perfectly localized. At the opposite extreme, for the example of a completely delocalized spin excitation we have the quasi-probability profile pn = 1/N. It corresponds to the point R = 0 at the origin of the unit circle, with the spread parameter σ = ∞ indicating that the excitation is completely delocalized (the argument μ is undefined in this case, since the excitation spread uniformly across the chain has no well-defined position). We can thus interpret R(t) as a vector on the complex plane, where drift of the localized excitation corresponds to rotation of R(t) about the origin, and delocalization corresponds to a shrinking of the magnitude of R(t). Taken together, these allow us to conveniently visualize different kinds of transport dynamics on the unit circle: diffusion and thermalization cause R(t) to move towards the origin, and coherent transport of an excitation through the system is realized as rapid rotation of R(t) around the origin.

Our decision to characterize transport via the circular mean R(t), and via μ(t) and σ(t) as defined in (12) (rather than linear first and second moments of pn51,76,77) is based on exploiting wrapped normal distributions as possible descriptions of systems with periodic boundary conditions. Our reasoning is as follows: the spreading of excitations in many-body systems is commonly modeled by a Gaussian distribution78,79. This finds good correspondence with the classical diffusion equation, which in the one dimensional system is

Here, an initial delta-function f = δ(x − x0) (analogous to our initial state of (8)) experiences a decay of its peak ~t−1/2 and growth of the standard deviation as ~t1/2. Our model has periodic boundary conditions such that when the excitation, and thus the tails of the associated quasi-probability distribution, reach the boundary, they “wrap around” the edge and self-interact. The dynamics of the quasi-probability distribution can thus heuristically be captured by a wrapped normal distribution of the form:

where the summation over k wraps the underlying normal distribution around the boundary, capturing the interactions of particles that diffuse across boundaries. For such a distribution, the bare parameters μ and σ in (14) are extracted precisely from the circular mean of (11) via (12). A potential limitation of this approach is that connection between σ(t) and an underlying spread parameter of (14) only holds for systems that realize an approximately wrapped Gaussian form for their magnetization profiles. From Fig. 3, we see that this connection holds everywhere except in c and g: the swappy regime, which exhibits the staggered patterning at early times, which (see end of Sec. “Analysis of the results”). In this case, we instead exploit the mean position μ(t), from which we extract a drift speed, to characterize the swappy regime.

In Fig. 4 we show the dynamics of R(t) for our the four regimes of our model for the first t = 100 time steps. We see that for the localized regime (•), there is no transport of any kind, R(t) remains close to its initial value for all times and trajectories. In the ergodic regime (▸), the trajectory exhibits rapid thermalization, ∣R(t)∣ → 0, but no coherent information transport occurs. In the swappy regime (■), coherent information transport is observed, as Arg[R(t)] varies at a relatively constant rate, in tandem with eventual thermalization, as ∣R(t)∣ → 0. Finally, in the near-SWAP regime (⋆), coherent information transport persists at a constant rate even at late times, with no noticeable equilibration, and ∣R(t)∣ remains equal to 1 throughout.

Representations of R(t) on the complex plane, within the unitary circle, are shown for the following values of J: (•) J = 0.395 (localized), (▸) J = 1.374 (ergodic), (■) J = 2.551 (swappy), and (⋆) J = 3.138 (near-SWAP regime). A typical trajectory from the total Ω = 100 trajectories is highlighted with a gradient from blue to red, corresponding to t from 0 to 100, and N = 20. The remaining trajectories are displayed in gray.

We are now prepared to quantitatively characterize the transport properties across our four distinct dynamical regimes. To assess the drift of the initial excitation, which is notably pronounced in the swappy and near-SWAP regimes, we define an instantaneous drift speed:

which, in practice, we modify slightly to account for discontinuities when excitations cross the boundary (see (In practice, we find it more effective to evaluate coherent transport via an instantaneous drift speed, ν(t), derived from a modified mean parameter, \(\widetilde{\mu }(t)\), as follows:

where this modification restricts ∣θn∣ ∈ [0, π] and addresses discontinuities in μ(t) that arise as excitations cross the boundary’s coordinate discontinuity. Numerical evidence supporting the presence of these discontinuities is presented in Fig. 4)). To further quantify the spread of the excitation, most prominently observed in the ergodic regime, we fit the parameter σ(t) to the form:

and determine the power-law exponent ασ.

To quantify the decay of the initial excitation due to its spread through the system, we track the maximum value \({p}_{\max }(t)=\mathop{\max }\limits_{n}{p}_{n}(t)\). This is fit to the form

where αp indicates the decay rate. As discussed, conventional diffusion corresponds to ασ (or αp) = 1/2, while ballistic transport aligns with ασ (or αp) = 1. Anomalous diffusion occurs with ασ (or αp) <1/2 for subdiffusion and >1/2 for superdiffusion.

From each trajectory R(t), we derive the spread σ(t) and drift speed ν(t) as per (12) and (15). Averaging over these realizations, denoted by 〈A〉, yields the sample-averaged spread 〈σ(t)〉 and speed 〈ν(t)〉. Figure 5 shows these averaged dynamics: a 〈σ(t)〉 and b 〈ν(t)〉, for a range of values J ∈ (0, π). The four points of interest are highlighted as bold black lines, labeled by their respective markers.

The dynamics of the realization-averaged parameters for various values of J ∈ (0, π), with N = 20 over 100 trajectories, is illustrated for: a the spread 〈σ(t)〉, b drift 〈ν(t)〉, and c decay of \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\). Four distinct regimes are marked with bold lines and symbols: (•) localized, (▸) ergodic, (■) swappy, and (⋆) near-SWAP. The gray-shaded areas in a and c highlight the time intervals used to fit the transport exponents ασ and αp, respectively. Due to stroboscopic sampling limitations, panel b is displayed only up to t = 100, effectively capturing all relevant behavior. Error bars are depicted as shaded semi-transparent regions where visible.

In Fig. 5a, we compute the spread parameter 〈σ(t)〉 behavior. In the localized regime (•), information spreads slowly and logarithmically even at late times, analogously to MBL in continuous-time systems. In the ergodic regime (▸), 〈σ(t)〉 grows as ~t1/2, indicating diffusion until equilibration at t ≈ 102, after which it saturates. The saturation of 〈σ(t)〉 to a constant contrasts with the expected divergence 〈σ(t)〉 → ∞ at equilibrium. However, Sec. S5 of the SM shows that this saturation is a finite-size effect vanishing as N → ∞. The swappy regime (■) exhibits rapid thermalization: initially super-diffusive transport, 〈σ(t)〉 ~ t, transitions to diffusion, 〈σ(t)〉 ~ t1/2, further explored in Fig. 5c. In the near-SWAP regime (⋆), spread remains minimal, with only a slight late-time increase in 〈σ(t)〉.

In Fig. 5b, the instantaneous transport speed 〈ν(t)〉 highlights distinct behaviors across regimes. In the localized regime (•), no movement occurs, with 〈ν(t)〉 ≈ 0 throughout. The ergodic regime (▸) shows non-zero speeds 〈ν(t)〉 > 0 at early times t < 10, but stabilizes to 〈ν(t)〉 ≈ 0 at later times. The swappy (■) and near-SWAP (⋆) regimes both display non-zero speeds for long times, with high values of 〈ν(t)〉 persisting to extremely long times as J → π approaches the SWAP point. The peak of 〈ν(t)〉 ≈ 2 aligns with the lightcone speed in brickwork circuits, reflecting the typicality of the permutation P and the Floquet unitary \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\), as discussed in Sec. S1 of the SM. Calculations are limited to t < 100 to avoid unreliable speed estimates at stroboscopically sampled times.

In Fig. 5c, we analyze the maximum value \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\). Its behavior resembles that of 〈σ(t)〉 in Fig. 5a but inverted: high \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\) values align with minimal spreading, while low values indicate a lack of spreading of the excitation. We see that, in the localized and near-SWAP regimes, \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\) remains constant, or decays extremely slowly, since the spread of the excitation is suppressed. In the ergodic and swappy regimes, however, the decay of \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\) is more rapid, consistent with the rapid spread of the excitation. We note that, taken together, our three quantities 〈σ(t)〉, 〈ν(t)〉 and \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\) allow us to distinguish the dynamical behaviors in our various regimes. For instance, the spread 〈σ(t)〉 shows very similar behavior for both the swappy (■) and ergodic (▸) regimes, but these two regimes are clearly distinguished by the speed 〈ν(t)〉. On the other hand, the speed 〈ν(t)〉 does not easily distinguish the dynamical behaviors in the localized (•) and ergodic (▸) regimes, but these are easily distinguished with the quantity \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\).

Here we process the realization-averaged spread, 〈σ(t)〉, the drift speed, 〈ν(t)〉, and the peak decay, \(\langle p_{\text{max}}(t)\rangle\), to obtain quantities suitable for scaling analysis of transport properties across system sizes N ∈ {14, 16, 18, 20, 22}.

To determine the transport exponent ασ from the transient behavior, \(\langle \sigma (t)\rangle \sim {t}^{{\alpha }_{\sigma }}\), we focus on intermediate-time regions exhibiting stable log-log behavior (shaded in gray in Fig. 5a). (To refine ασ, we perform 25 iterative fits, slightly varying the time window. Each time window is perturbed by a normally distributed factor with mean 1 and σ = 0.2. For each fit, 〈σ(t)〉 is computed from a third of the trajectories (randomly sampled). We then take the logarithm of 〈σ(t)〉 and t, fitting the data to \(b\;{\mathrm{ln}}\ t+c\), with ασ estimated as the mean of the b coefficients across all runs. This method minimizes sensitivity to both the time window choice and the average 〈σ〉 value. The same procedure is applied to \({p}_{\max }\) to estimate αp).

The results of the exponent extraction process are displayed in Fig. 6a. Two distinct flat regions emerge: one at ασ = 0 for very small J, and another at ασ ≈ 1/2 as J increases through the ergodic regime. As discussed, the value ασ = 1/2 indicates diffusive transport, though from Fig. 6a, it is unclear if ασ stabilizes at this value as N grows. Larger systems sizes would also be required to determine if the smooth transitions between these flat regions sharpens with increasing system size N, which would indicate a clearly defined localized-ergodic crossover. However, our finite-N results are consistent with the static results in Fig. 2.

In top a we see the diffusion exponents ασ extracted from Fig. 5a. In the bottom, b reports the integrated speed for the on the time interval t ∈ [0, T], where T = N/2.

In terms of transport properties, this behavior corresponds to a crossover from no transport at very small values of J, through an extended sub-diffusive regime, into diffusive transport. As J enters the swappy regime (highlighted as a shaded gray region), ασ drops sharply and becomes less stable, as indicated by the wider error bars. This instability is attributed again to the wrapped Normal distribution being an inadequate model for pn(t) in this regime (see Fig. 5c). We later observe a similar instability in \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\) in Fig. 7, wherein the transport exponent fluctuates drastically around unity. Close to the SWAP point J → π, the results stabilize as ασ rapidly approaches zero, indicating no spreading of the excitation.

In panel (a) we can see a stable area where αp ≈ 1/2 and a clear red area above it where the value of αp also surpasses 1. Although this last area does not allow to probe transport coefficients it allows to identify where the swappy regime takes place. In panel (b) th phase diagram of the exponent extracted from the decay of the \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\) at N = 20 averaged over 30 trajectories.

The results in Fig. 5b indicate that the total distance traveled by the excitation increases as J → π. It is thus instructive to define a time-averaged drift speed \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }\) as:

which spans from \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }=0\) in the localized phase to approximately \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }\approx 2\) as J → π, approaching the SWAP point. In this work, we take T to be the time needed for a SWAP circuit to return an excitation to its original position, T = N/νtyp, as discussed in Sec. S1 of the SM.

The results in Fig. 6b show smooth, stable behavior throughout the Jz = π line. We observe that \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }\) grows linearly across the localized and ergodic regimes, falling exactly to \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }=0\) in the fully-localized regime (J → 0). Additionally, \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }\) increases dramatically up to a maximum value of \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }=2\) beyond the point J ≈ 2.1 at which the transport exponent ασ breaks down in Fig. 6a. This behavior remains consistent across all system sizes N, but no clear crossover is visible, and a more comprehensive finite-size scaling analysis is needed to extract specific critical values and exponents.

In Fig. 5b, early-time drift is noticeable in both ergodic and swappy regimes but quickly stabilizes. A sharp rise in \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }\) in the destabilized ασ region (shaded gray in Fig. 6) suggests coherent late-time information transport. As N increases, we observe a small plateau at \(\overline{\langle \nu \rangle }=2\), consistent with Sec. S1 of the SM, implying that the swappy and near-SWAP regimes remain stable for large N, except at ultra-late times.

We analyze the exponent αp derived from the peak value \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle \sim {t}^{-{\alpha }_{p}}\), using the same method applied for 〈σ(t)〉. As shown in Fig. 7a, we find more robust and scale-sensitive results than those in Fig. 6a. The plateaus at αp ≈ 0 (full localization) and αp ≈ 1/2 (diffusive transport) have stabilized, emerging clearly as scaling limits as N increases. Although results remain somewhat unstable as J approaches the swappy regime, a clearer structure is evident compared to Fig. 6a. Larger system sizes N generally increase αp in this region, indicating the onset of very rapid thermalization consistent with super-diffusive (αp > 1/2) transport exponents. At J → π, αp nearly vanishes, as expected, since no excitation spreading occurs in this limit.

Finally, we extract the transport exponent αp from \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle \sim {t}^{{\alpha }_{p}}\) across the entire phase diagram to assess the stability of all regimes away from the Jz = π line (and thus the validity of our schematic intuition in Fig. 1). These results are shown for N = 20 in Fig. 7b wherein we identify the four regimes unambiguously: (•) αp ≈ 0 in the localized regime, (▸) αp ≈ 1/2 in the ergodic regime, (■) αp > 1/2 in the swappy regime, and (⋆) αp ≈ 0 in the near-SWAP regime as we approach the DU line. Figure 7b also shows clear crossovers between these regimes. with the localized-ergodic crossover consistent with gap ratio results shown in Fig. 2b. Surprisingly, away from Jz = π we find exponents consistent with ballistic αp ≈ 1 transport or super-ballistic αp > 1 transport; though the connection between the relaxation of local observables to true transport properties is tenuous, and the nature of transport via e.g., conductance measurements is a topic worth interrogating in future research. We discuss these large exponents again in the heuristic analysis of the swappy regime in the next section.

These results collectively establish the existence of a swappy regime as a distinct feature unique to discrete-time many-body systems, and located between the ergodic regime and DU line. Here we interrogate the stability and nature of this regime.

Based on our previous results, we expect that in the swappy and near-SWAP regimes, the system will eventually fully thermalize at very late times. However, in this section, we argue that these regimes are characterized by prethermal behavior, i.e., that the time needed for thermalization diverges as we approach the integrable SWAP point. To verify this interpretation of the swappy regime, we present a numerical investigation of the time taken for the system to thermalize. We estimate thermalization times via two operational definitions: \(t_\sigma\), the first time at which \(\langle\sigma(t)\rangle\) exceeds a threshold, and \(t_p\), the first time at which \(\langle p_{\text{max}}(t)\rangle\) falls below a threshold. We expect these to give similar results. We examine the behavior of the thermalization timescale as a function of the parameter \({J}^{{\prime} }=\pi -J\), which represents the deviation of J from the integrable SWAP point at J = π, and at which we expect the thermalization time to diverge. Our numerical results are plotted in Fig. 8a, b. We see that, as \({J}^{{\prime} }\) decreases to zero (i.e., as we approach the SWAP point) the thermalization times diverge as \({t}_{p}\propto {({J}^{{\prime} })}^{-2.6}\) and \({t}_{\sigma }\propto {({J}^{{\prime} })}^{-2.4}\). Both exhibit a power-law scaling with an exponent ≈2 that is expected generically for prethermalization due to proximity to an integrable point53. This implies the existence of an extended prethermal swappy regime. We note that the precise numerical values of the power-law exponents for the thermalization times are contingent on our ad-hoc choice of the threshold values for \(\langle {p}_{\max }(t)\rangle\) and 〈σ(t)〉 that determine our thermalization condition. However, we have checked that the exponents are ≈2 for a broad range of threshold values.

Discussion

Our results address transport across various phases of a highly generic U(1)-symmetric disordered Floquet model, revealing a wide array of phenomenological behaviors. This includes more conventional localized and ergodic regimes, exhibiting sub-diffusive and diffusive transport respectively; and the existence of a “swappy” regime unique to discrete-time quantum systems, in which excitations propagate ballistically. To enable this investigation, we study the model from both static and dynamic perspectives, by focusing in the zero magnetization subsector. The former is pursued by means of POLFED, adapted to work in a given magnetization subsector by applying the unitary gate-by-gate. We have developed and deployed the first circular moment (see Fig. 4 and discussion thereof): a quantity defined for periodic systems that directly encodes their transport properties, and which maps their aggregated dynamics onto simple yet striking two-dimensional diagrams. This quantity provides a visual and intuitive way to understand transport across different regimes in periodic systems; and, as it is singularly composed of local Z-basis expectation values, is highly amenable to experimental implementation; paving the way for the near-future experimental analysis of transport in digital matter. Of this quantity we analyze the decay, connected to the spread of the initial excitation, and speed of its phase, from which we define a notion of drift. Our drift might be linked to the concept of entanglement speed80,81, particularly in the near-SWAP regime, where it aligns with the characteristics of entanglement speed in DU circuits.

We emphasize that the dynamics studied here are not obtained from a simple Trotterization of a continuous-time disordered XXZ Hamiltonian because the disorder strength in our model does not scale with the kicking parameters. Physically, our protocol corresponds to strong static disorder that is periodically interrupted by finite unitary kicks. The non-scaling of disorder produces interference effects and a nearby discrete-time integrable point that do not survive the usual continuous-time limit; these give rise to qualitatively new transport behavior, in particular the “swappy” regime, which we identify and characterize below. Moreover, the circular statistical moments we use are directly measurable in current quantum-simulator experiments, providing an immediate route to test the predicted Floquet-specific phenomena.

Our results, taken in concert, demonstrate the existence of a swappy regime which is (i) distinct: exhibiting a clear ergodic-swappy crossover in the vicinity of J ~ 2.1 for all investigated dynamical quantities, (ii) dynamical: as it is absent in the static analyses, (iii) prethermal: exhibiting a failure to thermalize until late timescales which grow as a power law in t ~ (π−J)−2 (see end of Sec. “Analysis of the results”), (iv) stable to perturbations in J and Jz (see Fig. 7b and discussion thereof), (v) stable as a function of system size (see e.g., Figs. 6 and 8), and (vi) unique to discrete-time Floquet systems, appearing in the vicinity of the DU line at J = π, which has no counterpart in continuous models. We also provide a rough outline of a potential semi-classical mechanism underlying this regime; though we defer a detailed analysis of this mechanism to future study.

Methods

POLFED

The entanglement entropy values we compute are derived from the mean of \(\min (d/10,750)\) eigenvectors. To acquire these eigenvectors, we employ polynomial filtered diagonalization (POLFED)82, a spectral transformation akin to the shift-invert method, tailored for unitary matrices. The Floquet operator \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\) is redefined as the operator

This new operator is non-unitary yet retains the eigenvectors of the original Floquet operator. Moreover, the eigenphases of \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\) within the interval delimited by (ϕtgt ± 2π/K) are now transformed such that their absolute values exceed 1, while the others are less than 1. This enhances the convergence properties of the Arnoldi method, which we employ to derive the eigenphases and eigenvectors of \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\). In this study, we consistently selected ϕtgt = 0. For the parameter K, we adopted the recommendation from ref. 63,82, setting K to \(0.4\,d/\min (d/10,750)\).

Efficient time evolution of a state by a random circuit

The numerical method we developed circumvents the need to construct the entire \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\) matrix. Instead, we apply each gate directly to the state vector, leveraging the fact that both static and dynamic analyzes necessitate the application of the Floquet operator to a state. This allows the memory cost of diagonalizing \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\) to be O(d) and the number of operations to be O(Ld), similar to what pointed out in ref. 53.

Our approach involves recording the action of a gate on the first two spins of a state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\). If a gate acts on spins a and a + 1, we shift the system by −a sites, apply the gate to the first two spins, and then shift the system back to its original configuration.

To implement this, we require two key components. First, we must determine the value of the first two spins for each element of \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\). The state is represented as a d-vector:

where the i-th element corresponds to the \(\left|i\right\rangle\) state. Hence, we need to identify which segments of the d-vector have the first and second spins up, namely which of the ci are associated with a \(\left|i\right\rangle\) with first and second spin up.

The second ingredient involves the transformation f(1), which maps a state from sites 0,…,N − 1 to the corresponding state on sites N − 1,0,…,N − 2. By recursively applying f(1), we can achieve the required shift, i.e., \({f}_{(a)}={f}_{(1)}^{a}\). This strategy offers a significant memory advantage, as it only necessitates storing vectors of size d. Although this comes with a cost in the number of operations—each gate of \(\widehat{{\mathbb{U}}}\) or \(\widehat{{\mathbb{K}}}\) must be applied sequentially—the memory efficiency of this method allows for better parallel computation of multiple trajectories, which is crucial for disorder averaging.

Efficient computation of the entropy in a magnetization subsector

To compute the entropy, we can reduce the computation to different magnetization sub-sectors. Specifically, the entanglement entropy, given by (4), can be calculated by reshaping the state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) into a \({d}_{{N}_{A}}\times {d}_{{N}_{B}}\) matrix and extracting its Schmidt coefficients si via Singular Value Decomposition (SVD). The von Neumann entropy of \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) is then

Among these steps, the SVD is the most computationally intensive. However, we can exploit the structure of the system further. The space \({d}_{{N}_{A}}\) can be decomposed as

Given that \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) resides in \({{\mathcal{H}}}^{(M)}\) with M = 0, if the A part has magnetization MA, the B part will have magnetization MB = M − MA. Consequently, for each MA value we can isolate the component of \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) in \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{A,({M}_{A})}^{(M)}\), reshape it into a \({d}_{{N}_{A},({M}_{A})}^{(M)}\times {d}_{{N}_{B},({M}_{B})}^{(M)}\) matrix, and compute the SVD on this smaller matrix. In other terms, we split the zero-magnetization sub-sector as

The total entanglement entropy of the state is then given by

By sidestepping the full d-state vector’s SVD, the process of extracting entanglement entropy becomes more efficient and significantly more manageable.

Equilibrium diagnostics and their interpretation

We briefly justify why the diagnostics used in the analysis of the spectral properties of the model, the mean eigenstate entanglement entropy and the mean gap ratio, characterize equilibrium behavior in the infinite-time limit.

For a closed many-body system, an initial state \(\left|\psi (0)\right\rangle ={\sum }_{n}{c}_{n}\left|{E}_{n}\right\rangle\) dephases at late times, and observables are governed by the diagonal ensemble

where the time average is defined in (19) with T → ∞, such that infinite-time averages are fixed by eigenstate expectation values. ETH gives a statistical (RMT-like) form for matrix elements, implying that typical eigenstates at a given energy have thermal reduced states83,84. The Page result provides the quantitative benchmark for entanglement of a random pure state (and its variants for fixed-charge sectors), hence, if eigenstates are effectively random within the relevant symmetry/charge sector, the mean eigenstate von Neumann entropy should approach the corresponding Page value64,65. In practice, we therefore compare the numerically obtained mean eigenstate entanglement to the Page value computed in the fixed-magnetization subsector (see main text and (5) above). Deviations from the Page value indicate either finite-size corrections or a breakdown of eigenvector randomness (e.g., integrability, many-body localization, or scarred eigenstates).

The mean gap ratio (6) is a purely spectral statistic that distinguishes Wigner-Dyson (level repulsion) from Poisson (level clustering) statistics. Wigner–Dyson statistics signal RMT-like eigenvectors85, which underpins the randomness assumption in ETH and the Page-like entanglement of typical eigenstates64. Thus, the gap ratio (spectral correlations) and the mean eigenstate entanglement (eigenvector/statistical properties) are complementary diagnostics of whether the system’s infinite-time behavior is thermal (ergodic) or non-thermal.

Data availability

All data is available at https://github.com/alessum/swappy.

code availability

The data and the code generated throughout this project can be found at github.com/alessum/swappy.

References

Trotter, H. F. On the product of semi-groups of operators. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 10, 545–551 (1959).

Suzuki, M. Fractal decomposition of exponential operators with applications to many-body theories and Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Lett. A 146, 319–323 (1990).

Berry, D. W., Childs, A. M., Cleve, R., Kothari, R. & Somma, R. D. Simulating Hamiltonian dynamics with a truncated Taylor series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 090502 (2015).

Low, G. H. & Chuang, I. L. Optimal Hamiltonian simulation by quantum signal processing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 010501 (2017).

Campbell, E. Random compiler for fast Hamiltonian simulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 070503 (2019).

Barison, S., Vicentini, F. & Carleo, G. An efficient quantum algorithm for the time evolution of parameterized circuits. Quantum 5, 512 (2021).

Fauseweh, B. Quantum many-body simulations on digital quantum computers: State-of-the-art and future challenges. Nat. Commun. 15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46402-9 (2024).

Richter, J. & Pal, A. Simulating hydrodynamics on noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices with random circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 230501 (2021).

Summer, A., Chiaracane, C., Mitchison, M. T. & Goold, J. Calculating the many-body density of states on a digital quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 013106 (2024).

Yoshioka, N. et al. Krylov diagonalization of large many-body Hamiltonians on a quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 16, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59716-z (2025).

Keenan, N., Robertson, N. F., Murphy, T., Zhuk, S. & Goold, J. Evidence of kardar-parisi-zhang scaling on a digital quantum simulator. npj Quantum Inf. 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59716-z (2023).

Mi, X. et al. Stable quantum-correlated many-body states through engineered dissipation. Science 383, 1332–1337 (2024).

AI, G. Q. et al. Observation of disorder-free localization and efficient disorder averaging on a quantum processor, arXiv:2410.06557 (2024).

Fischer, L. E. et al. Dynamical simulations of many-body quantum chaos on a quantum computer. arXiv:2411.00765 (2024).

Khemani, V., Lazarides, A., Moessner, R. & Sondhi, S. L. Phase structure of driven quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 250401 (2016).

Mi, X., Ippoliti, M., Quintana, C. et al. Time-crystalline eigenstate order on a quantum processor. Nature 601, 531–536 (2021).

Skinner, B., Ruhman, J. & Nahum, A. Measurement-induced phase transitions in the dynamics of entanglement. Phys. Rev. X 9, 031009 (2019).

Turkeshi, X., Biella, A., Fazio, R., Dalmonte, M. & Schiró, M. Measurement-induced entanglement transitions in the quantum ising chain: from infinite to zero clicks. Phys. Rev. B 103, 224210 (2021).

Noel, C. et al. Measurement-induced quantum phases realized in a trapped-ion quantum computer. Nat. Phys. 18, 760–764 (2022).

Logarić, L., Dooley, S., Pappalardi, S. & Goold, J. Quantum many-body scars in dual-unitary circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 010401 (2024).

Andrade, B., Bhattacharya, U., Chhajlany, R. W., Graß, T. & Lewenstein, M. Observing quantum many-body scars in random quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. A 109, 052602 (2024).

Moudgalya, S. & Motrunich, O. I. Hilbert space fragmentation and commutant algebras. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011050 (2022).

Han, Y., Chen, X. & Lake, E. Exponentially slow thermalization and the robustness of Hilbert space fragmentation, arXiv:2401.11294 (2024).

Logarić, L., Goold, J. & Dooley, S. Hilbert subspace ergodicity. Phys. Rev. B 111, 144310 (2025).

Piroli, L. & Cirac, J. I. Quantum cellular automata, tensor networks, and area laws. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 190402 (2020).

Vanicat, M., Zadnik, L. & Prosen, T. Integrable trotterization: local conservation laws and boundary driving. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 030606 (2018).

Ljubotina, M., Zadnik, L. & Prosen, T. Ballistic spin transport in a periodically driven integrable quantum system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 150605 (2019).

Ljubotina, M., Žnidarič, M. & Prosen, T. Kardar-parisi-zhang physics in the quantum heisenberg magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 210602 (2019).

Bethe, H. Zur theorie der metalle: I. eigenwerte und eigenfunktionen der linearen atomkette. Z. Phys. 71, 205–226 (1931).

Bertini, B., Collura, M., De Nardis, J. & Fagotti, M. Transport in out-of-equilibrium xxz chains: exact profiles of charges and currents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 207201 (2016).

Žnidarič, M., Scardicchio, A. & Varma, V. K. Diffusive and subdiffusive spin transport in the ergodic phase of a many-body localizable system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 040601 (2016).

Prosen, T. Open xxz spin chain: nonequilibrium steady state and a strict bound on ballistic transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 217206 (2011).

Pal, A. & Huse, D. A. Many-body localization phase transition. Phys. Rev. B 82, 174411 (2010).

Luitz, D. J., Laflorencie, N. & Alet, F. Many-body localization edge in the random-field Heisenberg chain. Phys. Rev. B 91, 081103 (2015).

Abanin, D. A., Altman, E., Bloch, I. & Serbyn, M. Colloquium: many-body localization, thermalization, and entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 021001 (2019).

Nico-Katz, A., Bayat, A. & Bose, S. Memory hierarchy for many-body localization: Emulating the thermodynamic limit. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 033070 (2022).

Nico-Katz, A., Bayat, A. & Bose, S. Information-theoretic memory scaling in the many-body localization transition. Phys. Rev. B 105, 205133 (2022).

Serbyn, M., Papić, Z. & Abanin, D. A. Quantum quenches in the many-body localized phase. Phys. Rev. B 90, 174302 (2014).

Serbyn, M., Papić, Z. & Abanin, D. A. Criterion for many-body localization-delocalization phase transition. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041047 (2015).

Khemani, V., Sheng, D. N. & Huse, D. A. Two universality classes for the many-body localization transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 075702 (2017).

Luitz, D. J., Khaymovich, I. M. & Lev, Y. B. Multifractality and its role in anomalous transport in the disordered XXZ spin-chain. SciPost Phys. Core 2, 006 (2020).

Nico-Katz, A. & Bose, S. Entanglement-complexity geometric measure. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013041 (2023).

Colbois, J., Alet, F. & Laflorencie, N. Interaction-driven instabilities in the random-field xxz chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 116502 (2024).

Prosen, T. Time evolution of a quantum many-body system: transition from integrability to ergodicity in the thermodynamic limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1808–1811 (1998).

Prosen, T. Ergodic properties of a generic nonintegrable quantum many-body system in the thermodynamic limit. Phys. Rev. E 60, 3949–3968 (1999).

Prosen, T. General relation between quantum ergodicity and fidelity of quantum dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 65, 036208 (2002).

Sierant, P., Lewenstein, M., Scardicchio, A. & Zakrzewski, J. Stability of many-body localization in Floquet systems. Phys. Rev. B 107, 115132 (2023).

Gopalakrishnan, S. & Lamacraft, A. Unitary circuits of finite depth and infinite width from quantum channels. Phys. Rev. B 100, 064309 (2019).

Bertini, B., Kos, P. & Prosen, T. Exact correlation functions for dual-unitary lattice models in 1 + 1 dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 210601 (2019).

Peierls, R. Zur Theorie des Diamagnetismus von Leitungselektronen. Z. Phys. 80, 763–791 (1933).

Bar Lev, Y., Cohen, G. & Reichman, D. R. Absence of diffusion in an interacting system of spinless fermions on a one-dimensional disordered lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 100601 (2015).

Sünderhauf, C., Pérez-García, D., Huse, D. A., Schuch, N. & Cirac, J. I. Localization with random time-periodic quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. B 98, 134204 (2018).

Morningstar, A., Colmenarez, L., Khemani, V., Luitz, D. J. & Huse, D. A. Avalanches and many-body resonances in many-body localized systems. Phys. Rev. B 105, 174205 (2022).

Hahn, D. & Colmenarez, L. Absence of localization in weakly interacting Floquet circuits. Phys. Rev. B 109, 094207 (2024).

Shtanko, O. et al. Uncovering local integrability in quantum many-body dynamics. Nat. Commun. 16, 2552 (2025).

Long, D. M., Crowley, P. J. D., Khemani, V. & Chandran, A. Phenomenology of the prethermal many-body localized regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 106301 (2023).

Khemani, V., Vishwanath, A. & Huse, D. A. Operator spreading and the emergence of dissipative hydrodynamics under unitary evolution with conservation laws. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031057 (2018).

Rakovszky, T., Pollmann, F. & von Keyserlingk, C. W. Diffusive hydrodynamics of out-of-time-ordered correlators with charge conservation. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031058 (2018).

Jonay, C., Rodriguez-Nieva, J. F. & Khemani, V. Slow thermalization and subdiffusion in u(1) conserving Floquet random circuits. Phys. Rev. B 109, 024311 (2024).

Zhang, J., Vala, J., Sastry, S. & Whaley, K. B. Geometric theory of nonlocal two-qubit operations. Phys. Rev. A 67, 042313 (2003).

Sierant, P., Lewenstein, M., Scardicchio, A., Vidmar, L. & Zakrzewski, J. Many-body localization in the age of classical computing*. Rep. Prog. Phys. 88, 026502 (2025).

Panda, R. K., Scardicchio, A., Schulz, M., Taylor, S. R. & žnidarič, M. Can we study the many-body localisation transition? Europhys. Lett. 128, 67003 (2020).

Sierant, P., Lewenstein, M. & Zakrzewski, J. Polynomially filtered exact diagonalization approach to many-body localization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 156601 (2020).

Page, D. N. Average entropy of a subsystem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 1291–1294 (1993).

Bianchi, E. & Dona, P. Typical entanglement entropy in the presence of a center: page curve and its variance. Phys. Rev. D. 100, 105010 (2019).

Atas, Y. Y., Bogomolny, E., Giraud, O. & Roux, G. Distribution of the ratio of consecutive level spacings in random matrix ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 084101 (2013).

D’Alessio, L. & Rigol, M. Long-time behavior of isolated periodically driven interacting lattice systems. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041048 (2014).

Oganesyan, V. & Huse, D. A. Localization of interacting fermions at high temperature. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155111 (2007).

De Roeck, W. & Huveneers, F. mc Stability and instability towards delocalization in many-body localization systems. Phys. Rev. B 95, 155129 (2017).

Thiery, T., Huveneers, F. mc, Müller, M. & De Roeck, W. Many-body delocalization as a quantum avalanche. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 140601 (2018).

Alet, F. & Laflorencie, N. Many-body localization: an introduction and selected topics. C. R. Phys. 19, 498–525 (2018).

Doggen, E. V., Gornyi, I. V., Mirlin, A. D. & Polyakov, D. G. Many-body localization in large systems: matrix-product-state approach. Ann. Phys. 435, 168437 (2021).

Lezama, T. L. M., Bera, S. & Bardarson, J. H. Apparent slow dynamics in the ergodic phase of a driven many-body localized system without extensive conserved quantities. Phys. Rev. B 99, 161106 (2019).

Nandkishore, R. & Huse, D. A. Many-body localization and thermalization in quantum statistical mechanics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 6, 15–38 (2015).

Sierant, P. & Zakrzewski, J. Challenges to observation of many-body localization. Phys. Rev. B 105, 224203 (2022).

Steinigeweg, R. & Gemmer, J. Density dynamics in translationally invariant spin- \(\frac{1}{2}\) chains at high temperatures: a current-autocorrelation approach to finite time and length scales. Phys. Rev. B 80, 184402 (2009).

Bertini, B. et al. Finite-temperature transport in one-dimensional quantum lattice models. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025003 (2021).

Berry, M. V. Regular and irregular semiclassical wavefunctions. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 10, 2083 (1977).

Roy, S., Lev, Y. B. & Luitz, D. J. Anomalous thermalization and transport in disordered interacting Floquet systems. Phys. Rev. B 98, 060201 (2018).

Zhou, T. & Harrow, A. W. Maximal entanglement velocity implies dual unitarity. Phys. Rev. B 106, L201104 (2022).

Rampp, M. A., Rather, S. A. & Claeys, P. W. Geometric constructions of generalized dual-unitary circuits from biunitarity. SciPost Phys. 18, 182 (2025).

Luitz, D. J. Polynomial filter diagonalization of large Floquet unitary operators. SciPost Phys. 11, 021 (2021).

Deutsch, J. M. Quantum statistical mechanics in a closed system. Phys. Rev. A 43, 2046–2049 (1991).

Srednicki, M. Chaos and quantum thermalization. Phys. Rev. E 50, 888–901 (1994).

Bohigas, O., Giannoni, M.-J. & Schmit, C. Characterization of chaotic quantum spectra and universality of level fluctuation laws. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 1–4 (1984).

Dekking, F. M., Kraaikamp, C., Lopuhaä, H. P. & Meester, L. E. A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1007/1-84628-168-7 (Springer London, 2005).

Acknowledgements

The simulations were performed on the Luxembourg national supercomputer MeluXina, and the authors thank the LuxProvide teams for their expert support. The authors thank members of the QuSys group for discussions throughout the project. A.S. and J.G. acknowledge Iman Marvian for insightful conversations. A.N.-K. acknowledges support through the SFI-IRC Postdoctoral Fellowship GOIPD/2025/1504. S.D. acknowledges support through the SFI-IRC Pathway Grant 22/PATH-S/10812. J.G. is supported by a SFI-Royal Society University Research Fellowship and is grateful to IBM Ireland and for generous financial support. A.S., A.N.-K., and J.G. gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Microsoft Ireland for their research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and development of the project. A.S., S.D., and A.N.-K. carried out the computational aspects of the work. A.S. wrote the initial manuscript and served as the corresponding author, with revisions made by A.S., A.N.-K., and S.D. throughout the peer review process. All authors, A.S., A.N.-K., S.D., and J.G., have contributed to, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Summer, A., Nico-Katz, A., Dooley, S. et al. Anomalous transport in U(1)-symmetric quantum circuits. npj Quantum Inf 12, 32 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01178-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01178-8