Abstract

FePS3 is a layered van der Waals (vdW) Ising antiferromagnet that has recently been studied in the context of true 2D magnetism and emerged as an ideal material platform for investigating strong spin-phonon coupling, and non-linear magneto-optical phenomena. In this work, we demonstrate an important unresolved role of spin-orbit coupling (SOC) in the ground state and excitations of this compound. Combining first-principles calculations with linear flavor wave theory (LFWT), we find strong mixing and spectral overlap of different spin-orbital single-ion states. Low-lying excitations form hybrid spin-orbit exciton/magnon modes. Complete parameterization of the low-energy model requires nearly half a million coupling constants. Despite this complexity, such a model can be inexpensively derived using local many-body-based approaches, which yield quantitative agreement with recent experiments. The results highlight the importance of SOC even in first-row transition metals and provide essential insight into the properties of 2D magnets with unquenched orbital moments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

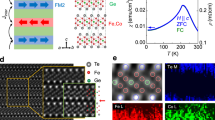

Two-dimensional (2D) van der Waals magnets have recently been intensively investigated for fundamental developments and potential applications in heterostructure devices1,2,3,4,5. One such material is FePS3, which exhibits a large Ising anisotropy of the local moments6,7, allowing retention of (zigzag) antiferromagnetic order down to the monolayer limit8. This fact, combined with the ease of exfoliation of few-layer samples of FePS3, has facilitated recent studies of, e.g., proximity effects in magnet-semiconductor heterostructures9, cavity manipulation of electromagnetic responses via strong light-matter coupling10, and giant non-linear optical responses11. The material has also emerged as an ideal platform for studying strong spin-phonon coupling12, as it exhibits the clear formation of optical magnon-polarons13,14,15,16 and a large modification of the lattice dynamics with magnetic state17,18,19,20. A similar effect leads to the possibility of topologically nontrivial phonon-magnon hybrid modes21,22,23,24 in FePS3 and the isostructural FePSe3.

The bulk magnetic excitations of FePS3 have also been extensively studied, via inelastic neutron scattering (INS)25,26,27, magneto-Raman28, and THz spectroscopy29. Particularly intriguing is ref. 29, which proposed to observe high energy 4-magnon bound states. However, to date, the majority of such works have analyzed the response of FePS3 with reference to phenomenological models with spin S = 2, referring to the four unpaired electrons at each high-spin d6 Fe2+ site. As we discuss in this work, such models ignore the unquenched local orbital degrees of freedom, which are necessary for the strong Ising anisotropy of the local moments30,31, and play a significant role in related Fe2+ materials32,33. Experimental evidence for large orbital moments in FePS3 can be seen in recent X-ray absorption spectroscopy branching ratio and linear dichroism measurements34. Thus, we raise a fundamental question: Is FePS3 an S = 2 system? The definitive answer is, “No.” Utilizing a systematic first-principles-based approach to construct the low-energy model, we instead show that the local moments are rich mixtures of spin-orbit entangled Jeff = 1, 2, and 3 states. The low-lying magnetic excitations alter both the orbital composition and moment orientations, thus being described as hybrid spin-orbit exciton (SOE)-magnon modes. These findings are relevant for a complete microscopic understanding of the intriguing magnetic, phononic, and optical properties of FePS3.

Results

Single-site states

At the single-site level, the high-spin d6 case has electronic configuration \({({t}_{2g})}^{4}{({e}_{g})}^{2}\), which corresponds to S = 2 and Leff = 1. The latter orbital momentum has been largely ignored in various recent works, which treated FePS3 as an S = 2 system. Instead, when spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is considered, the low-energy single-ion states are split into Jeff = 1, 2, and 3 multiplets30,35, as shown in Fig. 2a. These states are further split by the crystal field, which has approximately trigonal symmetry in FePS3. The basis functions for the pure Jeff multiplets are given in Supplementary Note 1. As discussed below, due to the relative weakness of SOC, intersite couplings are sufficiently strong to significantly mix and reorder these single-ion levels, such that the local moments and excitations develop a mixed Jeff character.

Electronic Hamiltonian

In order to develop a low-energy model for FePS3, we use the des Cloizeaux effective Hamiltonian (dCEH) approach36,37 to compute interactions for each bond up to third neighbors. A description is given in the “Methods” section. We first consider an electronic Hamiltonian in terms of Fe 3d-orbitals, which is a sum of, respectively, one- and two-particle terms: \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{el}}}={{\mathcal{H}}}_{1p}+{{\mathcal{H}}}_{2p}\). The one-particle terms include intersite hopping, intrasite crystal field, and spin-orbit coupling, \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{1p}={{\mathcal{H}}}_{hop}+{{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{CF}}}+{{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{SO}}}\):

where \({c}_{i,\alpha ,\sigma }^{\dagger }\) creates an electron at site i, in orbital α, with spin σ. To estimate \({t}_{ij}^{\alpha \beta }\) and \({d}_{i}^{\alpha \beta }\), we perform density functional theory (DFT) calculations, as described in the “Methods” section.

For \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{2p}={{\mathcal{H}}}_{U}+{{\mathcal{H}}}_{Jnn}\), we consider both on-site and intersite terms, respectively. The on-site contributions are given by:

In the spherically symmetric approximation38, Uαβγδ are parameterized by the Slater parameters F0, F2, F4. We use F2 = 9.11 eV, F4 = 6.56 eV, in accordance with spectroscopic studies of high energy d-d transitions in FePS339. This leaves F0 (or equivalently, \({U}_{t2g}={F}_{0}-\frac{4}{49}({F}_{2}+{F}_{4})\)) as a free parameter in the calculation. The effects of this choice are discussed below; we ultimately conclude that Ut2g = 4.2 eV provides a good match with the experiment. For the intersite terms, we consider an additional nearest neighbor Hund’s coupling:

The physical origin of this term is the downfolding of the p-orbital Coulomb interactions associated with the sulfur ligands into the Fe d-orbital Wannier functions. The Wannier orbitals are, in reality, anti-bonding combinations of d- and p-orbitals. The usual ferromagnetic Goodenough-Kanamori superexchange40 arises from the residual effects of the ligand Hund’s coupling when d-orbitals of adjacent Fe atoms hybridize with p-orbitals of the same ligand. This term plays a primary role in establishing ferromagnetic nearest neighbor couplings in edge-sharing materials (see, e.g., ref. 41). The intersite Hund’s coupling coefficients \({J}_{H,ij}^{\alpha \beta }\) can, in principle, be estimated by constrained Random Phase Approximation (cRPA) calculations42,43. However, we have found that cRPA tends to overestimate the coefficients by an order of magnitude. Instead, we take a partially empirical approach. Projecting the p-orbital Coulomb interactions into the Wannier function basis gives the approximation:

where \({\phi }_{i,\alpha }^{n,\delta }\) is the wavefunction coefficient for the Wannier function at Fe site i and d-orbital α corresponding to the directly bonded sulfur atom n, and p-orbital δ ∈ {px, py, pz}. Un is the Hubbard repulsion between electrons in the same p-orbital at site n, and \({J}_{H}^{n}\) is the Hund’s coupling at site n. At this point, we approximate \({U}^{n}=2{J}_{H}^{n}\), and take the screened sulfur Hund’s coupling to be half of the atomic value44, namely \({J}_{H}^{n}=0.27\) eV. We then evaluate the sums over bridging sulfur atoms, employing the wavefunction coefficients obtained from DFT. While these choices are physically reasonable, this approach is further justified because it yields intersite magnetic couplings of experimentally correct magnitude, as shown below. The full estimated intersite \({J}_{H,ij}^{\alpha \beta }\) tensors are given in Supplementary Note 2; the largest coefficients are ~2 meV, and involve the eg orbitals, which hybridize more strongly than the t2g orbitals with the ligand p-orbitals.

Intersite low-energy couplings

With the electronic Hamiltonian thus defined, we obtain the low-energy model by exactly diagonalizing \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{el}}}\) on pairs of sites up to the third nearest neighbor and projecting the lowest energy eigenstates onto pure Jeff states (see Supplementary Note 1 for full definition). In general, the resulting low-energy model takes the form:

where \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{i}^{n}\) are local operators that act in the local basis, which may include up to Jeff = 1, 2, and 3 states.

In Fig. 3a, we first show the evolution of the state energies as a function of Ut2g for a two-site cluster representing the Z1-bond. It is instructive to first consider the large Ut2g limit, where states of different J are somewhat separated in energy. In this limit, it is possible to constrain the low-energy model to the lowest three states on each site, which are smoothly connected to pure Jeff = 1 triplets (nine states for the pair of sites). In this case, the \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{i}^{n}\) operators may be chosen as the conventional spherical tensor (Stevens) operators for S = 1. The Hamiltonian may then be written:

where the bilinear couplings are parameterized by

for the Z-bonds, in terms of the global (x, y, z) coordinates defined in Figs. 1 and 2b, c. In Fig. 3b, c, we show the evolution of the couplings for the Z1 and Z3 bonds obtained by projecting the lowest 9 states onto pure Jeff = 1 states. A full discussion of the biquadratic couplings \({B}_{ij}^{nm}\) is found in Supplementary Note 3. There are several important observations: (1) We find a large single-ion anisotropy (SIA) with A ≈ −5.1 meV, independent of Ut2g. This arises from the local trigonal distortion of the FeS6 octahedra, which split the Jeff = 1 levels. (2) The intersite exchange couplings are quite anisotropic. The nearest neighbor Kitaev coupling K1 is antiferromagnetic, but small compared to the other couplings. The third neighbor, K3, is negligible. Instead, the largest anisotropic couplings are \({\Gamma }_{n}\approx {\Gamma }_{n}^{{\prime} }\), which have the same sign as the corresponding Heisenberg couplings Jn. This implies a significant bond-independent Ising exchange anisotropy, with the Ising axis along the c*-axis. Microscopically, the origin of this exchange anisotropy is precisely the same as the SIA: the modification of the local moments by the trigonal crystal field. Both the exchange anisotropy and SIA must be present together. (3) There is significant anisotropic nearest neighbor biquadratic (BQ) exchange. Full details are given in Supplementary Note 3; the Z-bond BQ terms are parameterized by nine symmetry-distinct constants, which we find are typically on the order of 10% of J1. It may be noted that large BQ exchange was recently implicated to explain the specific dispersion of excitations in inelastic neutron scattering experiments27, although this was in the context of an S = 2 model.

a Evolution of lowest energy eigenvalues for two-site Z1-bond cluster. States are colored according to their composition in terms of Jeff states. For Ut2g ≤ 5 eV, Jeff = 2 states intrude into the low-energy space, invalidating a pure Jeff = 1 model. b, c Evolution of bilinear couplings in Jeff = 1 model for large Ut2g for first and third neighbors, respectively. Second neighbor couplings are an order of magnitude smaller and are not shown.

While these observations for the large U case may provide some intuition into the intersite couplings, the Jeff = 1 picture breaks down for Ut2g ≤ 5 eV, as the higher lying Jeff = 2 states descend into the low-energy window. This is depicted in Fig. 3a. As we show below, the physically applicable value is Ut2g ≈ 4.2 < 5 eV. Thus, it is not possible to map the low-energy space onto a single J multiplet, so all 15 local Jeff = 1, 2, and 3 states need to be considered explicitly in the low-energy model. Complete specification of the Hamiltonian therefore requires 152 = 225 local operators, such that each bond interaction is defined by \({(1{5}^{2}-1)}^{2}=50,176\) coupling constants \({J}_{ij}^{nm}\). Figure 4a, b shows the distribution and magnitudes of such couplings for the Z1 bond obtained by the dCEH method for Ut2g = 4.2 eV; the fact that there is no clear separation of magnitudes implies the need to retain all couplings. This situation highlights the utility of many-body approaches, such as the above-described dCEH approach, for the estimation of low-energy Hamiltonians (see refs. 45,46,47,48,49 for a survey of approaches). The many-body nature of the local spin-orbital states and large number of couplings would present a significant difficulty for more traditional pure-DFT approaches in which couplings are estimated from energy differences between suitably constrained Kohn-Sham (single determinant) wavefunctions50,51,52. In the above-described dCEH approach, all couplings are instead obtained simultaneously for a given bond from a single diagonalization of the two-site electronic Hamiltonian, which requires at most a few minutes on a single workstation. In lieu of printing these couplings, we provide the corresponding bond matrices in matrix market53 (.mtx) format in the Supplementary Material to facilitate future studies.

a Plot of coupling interaction matrix indicating the location of different Jeff blocks for each site, for the Z1 bond and Ut2g = 4.2 eV for full Jeff = 1, 2, and 3 model. A constant has been subtracted from the diagonal to make the matrix traceless for plotting. b Histogram showing the distribution of the magnitude of matrix elements.

Model properties

From here, we consider only the full Jeff = 1, 2, 3 model with Ut2g = 4.2 eV. In order to analyze the ground state and excitations, we employ a numerical linear flavor wave theory (LFWT) approach54,55,56,57,58,59, described in detail in the “Methods” section. We find that the full model reproduces all aspects of the experimental response of FePS3.

In agreement with the experiment, the mean-field model exhibits antiferromagnetic zigzag order of magnetic dipoles, which can be understood as arising from primarily ferromagnetic nearest neighbor and antiferromagnetic third neighbor couplings. The moment size is \(| \langle {\psi }_{i}^{0}| {\bf{L}}-2{\bf{S}}| {\psi }_{i}^{0}\rangle | =5.0{\mu }_{B}\), which is enhanced compared to the spin-only value of 4μB for S = 2. A similar enhancement has been reported both from neutron60,61 and susceptibility62 analysis.

For the zigzag wavevector along the b-axis, the moments are oriented in the ac*-plane, making an angle of 11° with the c* axis, as shown in Fig. 1. Previous neutron scattering data was analyzed in terms of the moments oriented precisely along the c* axis, although this is not required by symmetry. Future experiments could refine the moment direction. The composition of the MF ground state is 75% Jeff = 1, 23% Jeff = 2, and 2% Jeff = 3, demonstrating a significant mixture of different spin-orbital components. This mixing is driven both by the on-site crystal field and the (mean-field) effects of intersite coupling.

In principle, there are two classes of excitations of the magnetically ordered phase: magnon-like modes within the lowest Jeff manifold, and spin-orbit excitons (SOE) between different Jeff values. In FePS3, we find that these excitations are strongly mixed. The predicted dispersion of the hybrid SOE/magnon excitations is shown in Fig. 5a, with the color indicating the J-composition of the mode. In Fig. 5b, we show the predicted low-energy dynamical magnetic structure factor, defined by \({D}_{{\rm{mag}}}(q)={\sum }_{\mu }\int{e}^{i\omega t}[{L}_{-q}^{\mu }(t)-2{S}_{-q}^{\mu }(t)][{L}_{q}^{\mu }(0)-2{S}_{q}^{\mu }(0)]dt\). The intensity pattern matches well with the inelastic neutron scattering (INS) experiments25,26,27.

a Full magnon/spin-orbit exciton band structure, with bands colored according to their Jeff composition. b Dynamical magnetic structure factor Dmag(q) for the lowest energy bands. c Dynamical electrical polarization structure factor Del(q) for the lowest energy bands (see text for definition). d–f Evolution of the lowest excitations with magnetic field oriented along the c*-axis, with zero-field energy Δ and slope g indicated.

In accordance with INS experiments, the lowest branch forms two dispersive bands. We predict the gap at the Γ-point to be ~18 meV, which is somewhat larger than the experimental value of 15 meV. This discrepancy is likely due to an overestimation of the trigonal crystal field splitting at the DFT level. For example, a recent X-ray absorption study34 was well-modeled with an absolute splitting of the t2g orbitals on the order of ~10 meV, while we found a value of ~44 meV from the Wannier-interpolated crystal field terms. Apart from this discrepancy, the predicted dispersions of the excitations below 50 meV are in excellent agreement with INS experiments. Due to their differing spin-orbital composition, the population of the low-energy modes alters the J-composition of the local moments. For example, at q = 0, the eigenvector for the lower band corresponds to a composition of 53% Jeff = 1, 38% Jeff = 2, and 9% Jeff = 3. Similarly, the upper band has a composition of 65% Jeff = 1, 28% Jeff = 2, and 7% Jeff = 3. In both cases, relative weight is shifted from Jeff = 1 to Jeff = 2, highlighting the mixed SOE/magnon character of these modes. Another particular feature of the bands is the very weak dispersion along the Γ → Y and Z → C paths, which implies the excitations primarily propagate perpendicular to the ordering wavevector, i.e., along the ferromagnetic zigzag chains. This feature was discussed in ref. 27, and is naturally reproduced here.

Above the lowest branch, there is a flat band at ~57 meV. This band essentially represents the quadrupolar ΔmJ = ±2 modes of the lowest Jeff = 1 single-ion level. These modes correspond to a composition of 78% Jeff = 1, 13% Jeff = 2, and 9% Jeff = 3, which is similar to the composition of the ground-state moments. Beyond the LFWT approximation, we would expect this mode to hybridize with the 2-magnon continuum, which may lead to broadening. Finally, at higher energies, there are a number of modes between 70 and 170 meV, with mostly Jeff = 2 and 3 SOE character. These likely explain the broad absorption bands observed in the same region of energies via infrared and Raman measurements35,63.

We next consider the THz/infrared studies reported in ref. 29. These studies observed the main modes at 15.1, 39.6, and 57.5 meV, which correspond very well with the predicted energies of 18.3, 39.7, and 56.6 meV from LFWT (at q = 0). In Fig. 5d–f, we show the evolution of these modes with magnetic field applied along the out-of-plane c* direction. The modes at 18.3 and 39.7 meV each consist of a pair of excitations that are symmetrically split under applied field. These represent magnon-like excitations (ΔmJ ~ ±1), which are essentially confined to either a spin-up or spin-down sublattice. Based on the predicted slopes, we evaluate the effective g-values for the excitations to be 2.10 and 2.52, respectively. These values are in good agreement with the experimental value of 2.15 for both modes. The quadrupolar (ΔmJ ~ ±2) mode at 56.6 meV instead has a much larger slope, which we evaluate as g ≈ 7.3. Experimentally, it was found to be 9.2. While, naively, one might expect the energies of the ΔmJ ~ ±2 excitations to have twice the slope of the ΔmJ ~ ±1 excitations with respect to field, it should be emphasized that the spin-orbital composition of the excitations is quite different. The lower energy modes have significantly higher Jeff = 2 character, which reduces the effective g-value.

Finally, it is worth considering why the 39.7 meV mode has an appreciable intensity in the THz/infrared spectra. As shown in Fig. 5b, this band has vanishing weight in the dynamical magnetic structure factor near q = 0. This is because this mode is odd under inversion, while the magnetic dipole operator is even. In principle, the finite intensity may therefore reflect a lowering of symmetry in the bulk or a surface effect in thin samples. Here we present another possibility that arises from the orbital component of the excitations: in a sufficiently low-symmetry crystal field, these modes are electric dipole-active. In order to demonstrate this, we computed the electrical polarization operators in the dCEH basis from the matrix elements of P = −er between d-orbital Wannier functions on the same Fe site. In Fig. 5c, we show the predicted electric dipole structure factor, defined by \({D}_{{\rm{el}}}(q)={\sum }_{\mu }\int{e}^{i\omega t}{P}_{-q}^{\mu }(t){P}_{q}^{\mu }(0)dt\). For q = 0, this is proportional to the electric dipole absorption intensity, which contributes to THz/infrared spectra, but not INS. Since P is odd under inversion, this provides a route to observe the inversion-odd “exchange modes” without lowering of symmetry, provided such excitations significantly alter the orbital composition. In the present case of FePS3, where the magnons and SOEs are strongly mixed, this condition is satisfied. As shown in Fig. 5c, both the 39.7 and 56.6 meV excitations are electric dipole-active.

Discussion

In this work, we have investigated the low-energy model, ground state, and excitations of FePS3, which has been of growing interest in the context of 2D magnetism. Contrary to typical expectations for 3d transition metal compounds, SOC is very important to accurately model the low-lying excitations. In fact, the weakness of SOC compared to crystal field splitting and intersite exchange leads to spectral overlap and mixing of magnons and spin-orbit excitons to form hybrid excitations, the properties of which depend on their specific spin-orbital composition. We have shown that a comprehensive model including all local Jeff states, obtained from first principles calculations employing the dCEH approach, reproduces all essential experimental details with remarkable quantitative agreement. While these findings do not invalidate previous phenomenological models (e.g., spin-phonon coupling in FePS3) in terms of an S = 2 system, a complete microscopic picture of the intriguing optical, magnetic, and phononic properties should account for the large orbital moment. For example, due to the relative weakness of SOC, the specific spin-orbital composition of the local moments and excitations can be strongly perturbed by structural distortions, potentially enhancing spin-lattice coupling and sensitivity to symmetry breaking at the surface. Effects such as the giant surface optical second harmonic generation11, and strong spin-phonon coupling13,14,15,16 may therefore be rooted in SOC. Overall, the results highlight that complex spin-orbital phenomena may be found even in first-row transition metal compounds and that we have the tools to address them.

Methods

Density functional theory

Ab initio DFT calculations were performed starting from the experimental C2/m structure of FePS364 in order to parameterize the single-particle parts of the electronic Hamiltonian. These calculations employed the package FPLO65,66 and were performed at the GGA (PBE) level67 using a 12 × 12 × 12 k-grid for self-consistent calculations. Hopping integrals were obtained by projecting the resulting electronic bands onto Fe d-orbitals to construct Wannier functions68. We also repeated this procedure for fully relativistic calculations in order to check the effects of SOC on the single-particle Wannier Hamiltonian. From the comparison of the two calculations, we find that SOC is well captured by an on-site λL ⋅ S term with λ = 53 meV, the atomic value for Fe69, which was subsequently included in the derivation of the low-energy Hamiltonian. Imaginary intersite hoppings were negligible in the fully relativistic calculation and were subsequently omitted.

des Cloizeaux effective Hamiltonians

Calculations of the low-energy Hamiltonians were performed using the dCEH approach36,37. This is a standard method for extracting generic effective Hamiltonians, which act within an idealized low-energy Hilbert space (e.g., spanned by local spin/orbital degrees of freedom), from numerical eigenstates of a larger Hilbert space (e.g., a full electronic Fock space). In our implementation, the electronic Hamiltonian was first diagonalized on a finite number of Fe sites to obtain the low-energy eigenstates \(\left\vert {\phi }_{n}\right\rangle\) and energies En in terms of the electronic degrees of freedom. The low-energy Hamiltonian is then formally \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{low}}}={\sum }_{n}{E}_{n}\left\vert {\phi }_{n}\right\rangle \left\langle {\phi }_{n}\right\vert\). However, in order to interpret this expression, a mapping is required between the electronic states and the idealized low-energy spin-orbital states, \(\left\vert {\psi }_{n}\right\rangle\). As described in the “Results” section, this idealized basis may be chosen as pure Jeff = 1 states at each site in the case of large U but must include all Jeff = 1, 2, and 3 states for realistic values of U due to energetic overlap of different angular momenta. \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{low}}}\) was therefore rotated into the idealized low-energy space, via \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}={{\bf{S}}}^{-1/2}{\mathbb{P}}{{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{low}}}{\mathbb{P}}{{\bf{S}}}^{-1/2}\), where \({\mathbb{P}}={\sum }_{n}\left\vert {\psi }_{n}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{n}\right\vert\) is the projection operator onto the low-energy space, and S is the overlap matrix of the projected low-energy states, with matrix elements \({\left[{\bf{S}}\right]}_{nm}=\langle {\phi }_{n}| {\mathbb{P}}| {\phi }_{m}\rangle\). It may be noted that \(U={\mathbb{P}}{{\bf{S}}}^{-1/2}\) is a unitary operator (with \({U}^{\dagger }={{\bf{S}}}^{-1/2}{\mathbb{P}}\)), so this transformation preserves the local spectrum of \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{{\rm{low}}}\). For evaluation of expectation values, such as the magnetization or dipole matrix elements, the operators within the electronic Hilbert space were transformed accordingly, i.e., L − 2S → U†(L − 2S)U. This ensures the correct representation of these operators within the low-energy effective model.

Linear flavor wave theory

Calculations of the ground state and excitations of FePS3 were performed within the LFWT approach. The mean-field model

was first solved self-consistently. From this, the local eigenstates \(\left\vert {\psi }_{i}^{\alpha }\right\rangle\) were then employed to construct the LFWT Hamiltonian in terms of bosonic operators \({b}_{i,\alpha }^{\dagger }\equiv \left\vert {\psi }_{i}^{\alpha }\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{i}^{0}\right\vert\) where \(\left\vert {\psi }_{i}^{0}\right\rangle\) corresponds to the local ground state of the MF model at site i. Then, we may write:

where:

The linearized model was then diagonalized utilizing the standard Cholesky decomposition approach70,71. Following a similar approach, operators corresponding to the spin, orbital momentum, and electric dipole operators were constructed in terms of the bosonic operators \({b}_{i,\alpha }^{\dagger }\), and the q-dependent excitation intensities computed from the resulting eigenvectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Burch, K. S., Mandrus, D. & Park, J.-G. Magnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Nature 563, 47–52 (2018).

Mak, K. F., Shan, J. & Ralph, D. C. Probing and controlling magnetic states in 2D layered magnetic materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 646–661 (2019).

Li, H., Ruan, S. & Zeng, Y.-J. Intrinsic van der Waals magnetic materials from bulk to the 2D limit: new frontiers of spintronics. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900065 (2019).

McGuire, M. A. Cleavable magnetic materials from van der Waals layered transition metal halides and chalcogenides. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 110901 (2020).

Kurebayashi, H., Garcia, J. H., Khan, S., Sinova, J. & Roche, S. Magnetism, symmetry and spin transport in van der Waals layered systems. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 150–166 (2022).

Wildes, A. et al. High field magnetization of FePS3. Phys. Rev. B 101, 024415 (2020).

Nauman, M. et al. Complete mapping of magnetic anisotropy for prototype Ising van der Waals FePS3. 2D Mater. 8, 035011 (2021).

Lee, J.-U. et al. Ising-type magnetic ordering in atomically thin FePS3. Nano Lett. 16, 7433–7438 (2016).

Gong, C. et al. Ferromagnetism emerged from non-ferromagnetic atomic crystals. Nat. Commun. 14, 3839 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Cavity-enhanced linear dichroism in a van der Waals antiferromagnet. Nat. Photon. 16, 311–317 (2022).

Ni, Z., Huang, N., Haglund, A. V., Mandrus, D. G. & Wu, L. Observation of giant surface second-harmonic generation coupled to nematic orders in the van der Waals antiferromagnet FePS3. Nano Lett. 22, 3283–3288 (2022).

Wang, K., Ren, K., Hou, Y., Cheng, Y. & Zhang, G. Magnon–phonon coupling: from fundamental physics to applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 21802–21815 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Direct observation of magnon-phonon strong coupling in two-dimensional antiferromagnet at high magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 097401 (2021).

Zhang, Q. et al. Coherent strong-coupling of terahertz magnons and phonons in a Van der Waals antiferromagnetic insulator. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.11619 (2021).

Vaclavkova, D. et al. Magnon polarons in the van der Waals antiferromagnet FePS3. Phys. Rev. B 104, 134437 (2021).

Sun, Y.-J. et al. Magneto-raman study of magnon–phonon coupling in two-dimensional ising antiferromagnetic FePS3. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 1533–1539 (2022).

Ghosh, A. et al. Spin-phonon coupling and magnon scattering in few-layer antiferromagnetic FePS3. Phys. Rev. B 103, 064431 (2021).

Zhou, F. et al. Dynamical criticality of spin-shear coupling in van der Waals antiferromagnets. Nat. Commun. 13, 6598 (2022).

Ergeçen, E. et al. Coherent detection of hidden spin–lattice coupling in a van der Waals antiferromagnet. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2208968120 (2023).

Zong, A. et al. Spin-mediated shear oscillators in a van der Waals antiferromagnet. Nature 620, 988–993 (2023).

To, D.-Q. et al. Giant spin Nernst effect in a two-dimensional antiferromagnet due to magnetoelastic coupling-induced gaps and interband transitions between magnon-like bands. Phys. Rev. B 108, 085435 (2023).

Kløgetvedt, J. N. & Qaiumzadeh, A. Tunable topological magnon-polaron states and intrinsic anomalous Hall phenomena in two-dimensional ferromagnetic insulators. Phys. Rev. B 108, 224424 (2023).

Cui, J. et al. Chirality selective magnon-phonon hybridization and magnon-induced chiral phonons in a layered zigzag antiferromagnet. Nat. Commun. 14, 3396 (2023).

Luo, J. et al. Evidence for topological magnon–phonon hybridization in a 2D antiferromagnet down to the monolayer limit. Nano Lett. 23, 2023–2030 (2023).

Wildes, A., Rule, K. C., Bewley, R., Enderle, M. & Hicks, T. J. The magnon dynamics and spin exchange parameters of FePS3. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 24, 416004 (2012).

Lançon, D. et al. Magnetic structure and magnon dynamics of the quasi-two-dimensional antiferromagnet FePS3. Phys. Rev. B 94, 214407 (2016).

Wildes, A., Zhitomirsky, M., Ziman, T., Lançon, D. & Walker, H. Evidence for biquadratic exchange in the quasi-two-dimensional antiferromagnet FePS3. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 223903 (2020).

McCreary, A. et al. Quasi-two-dimensional magnon identification in antiferromagnetic FeP S3 via magneto-Raman spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 101, 064416 (2020).

Wyzula, J. et al. High-angular momentum excitations in collinear antiferromagnet FePS3. Nano Lett. 22, 9741–9747 (2022).

Chandrasekharan, N. & Vasudevan, S. Magnetism, exchange and crystal field parameters in the orbitally unquenched Ising antiferromagnet FePS3. Pramana 43, 21–31 (1994).

Kim, T. Y. & Park, C.-H. Magnetic anisotropy and magnetic ordering of transition-metal phosphorus trisulfides. Nano Lett. 21, 10114–10121 (2021).

Song, Y.-J., Lee, K.-W. & Pickett, W. E. Large orbital moment and spin-orbit enabled Mott transition in the Ising Fe honeycomb lattice of BaFe2(PO4)2. Phys. Rev. B 92, 125109 (2015).

Bai, X. et al. Hybridized quadrupolar excitations in the spin-anisotropic frustrated magnet FeI2. Nat. Phys. 17, 467–472 (2021).

Lee, Y. et al. Giant magnetic anisotropy in the atomically thin van der Waals antiferromagnet FePS3. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2200650 (2023).

Sanjuán, M., Kanehisa, M. & Jouanne, M. Electronic Raman study of Fe2+ in FePX3 (X = S, Se) layered compounds. Phys. Rev. B 46, 11501 (1992).

Des Cloizeaux, J. Extension d’une formule de Lagrange à des problèmes de valeurs propres. Nucl. Phys. 20, 321–346 (1960).

Soliverez, C. E. General theory of effective Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. A 24, 4 (1981).

Sugano, S., Tanabe, Y. & Kamimura, H. (eds) Multiplets of transition-metal ions in crystals in Pure and Applied Physics, Vol. 33 (Elsevier, 1970).

Joy, P. & Vasudevan, S. Optical-absorption spectra of the layered transition-metal thiophosphates MPS3 (M = Mn, Fe, and Ni). Phys. Rev. B 46, 5134 (1992).

Kanamori, J. Superexchange interaction and symmetry properties of electron orbitals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 10, 87–98 (1959).

Autieri, C. et al. Limited ferromagnetic interactions in monolayers of MPS3 (M = Mn and Ni). J. Phys. Chem. C 126, 6791–6802 (2022).

Şaşıoğlu, E., Friedrich, C. & Blügel, S. Effective Coulomb interaction in transition metals from constrained random-phase approximation. Phys. Rev. B 83, 121101 (2011).

Vaugier, L., Jiang, H. & Biermann, S. Hubbard U and Hund exchange J in transition metal oxides: screening versus localization trends from constrained random phase approximation. Phys. Rev. B 86, 165105 (2012).

Liska, M., Pelikán, P. & Nagy, L. T. Systematic determination of the Slater-Condon parameters of atoms and ions with K (2) L (8) 3sm3pnconfigurations. Chem. Pap. 29, 577–581 (1975).

Calzado, C. J., Cabrero, J., Malrieu, J. P. & Caballol, R. Analysis of the magnetic coupling in binuclear complexes. I. Physics of the coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 2728–2747 (2002).

Calzado, C. J., Cabrero, J., Malrieu, J. P. & Caballol, R. Analysis of the magnetic coupling in binuclear complexes. II. Derivation of valence effective Hamiltonians from ab initio CI and DFT calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 3985–4000 (2002).

Pourovskii, L. Two-site fluctuations and multipolar intersite exchange interactions in strongly correlated systems. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115117 (2016).

Riedl, K., Li, Y., Valentí, R. & Winter, S. M. Ab Initio approaches for low-energy spin Hamiltonians. Phys. Status Solidi B 256, 1800684 (2019).

Pourovskii, L. V., Mosca, D. F. & Franchini, C. Ferro-octupolar order and low-energy excitations in d2 double perovskites of osmium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 237201 (2021).

Pi, S.-T., Nanguneri, R. & Savrasov, S. Calculation of multipolar exchange interactions in spin-orbital coupled systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 077203 (2014).

Mosca, D. F., Pourovskii, L. V. & Franchini, C. Modeling magnetic multipolar phases in density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 106, 035127 (2022).

Szilva, A. et al. Quantitative theory of magnetic interactions in solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 035004 (2023).

Boisvert, R. F., Pozo, R. & Remington, K. A. The Matrix Market Exchange Formats: Initial Design. NIST Interagency/Internal Report (NISTIR) No. 5935 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 1996).

Joshi, A., Ma, M., Mila, F., Shi, D. & Zhang, F. Elementary excitations in magnetically ordered systems with orbital degeneracy. Phys. Rev. B 60, 6584 (1999).

Läuchli, A., Mila, F. & Penc, K. Quadrupolar phases of the S = 1 bilinear-biquadratic Heisenberg model on the triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 087205 (2006).

Tóth, T. A., Läuchli, A. M., Mila, F. & Penc, K. Three-sublattice ordering of the SU(3) Heisenberg model of three-flavor fermions on the square and cubic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 265301 (2010).

Luo, C., Datta, T. & Yao, D.-X. Spin and quadrupolar orders in the spin-1 bilinear-biquadratic model for iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 93, 235148 (2016).

Kim, F. H., Penc, K., Nataf, P. & Mila, F. Linear flavor-wave theory for fully antisymmetric SU(N) irreducible representations. Phys. Rev. B 96, 205142 (2017).

Koyama, S. & Nasu, J. Flavor-wave theory with quasiparticle damping at finite temperatures: application to chiral edge modes in the Kitaev model. Phys. Rev. B 108, 235162 (2023).

Kurosawa, K., Saito, S. & Yamaguchi, Y. Neutron diffraction study on MnPS3 and FePS3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 52, 3919–3926 (1983).

Coak, M. J. et al. Emergent magnetic phases in pressure-tuned van der Waals antiferromagnet FePS3. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011024 (2021).

Joy, P. & Vasudevan, S. Magnetism in the layered transition-metal thiophosphates MPS3 (M = Mn, Fe, and Ni). Phys. Rev. B 46, 5425 (1992).

Jouanne, M. & Julien, C. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy studies at low temperatures of MPX3 layered compounds. J. Appl. Phys. 64, 3637–3640 (1988).

Ouvrard, G., Brec, R. & Rouxel, J. Structural determination of some MPS3 layered phases (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni and Cd). Mater. Res. Bull. 20, 1181–1189 (1985).

Koepernik, K. & Eschrig, H. Full-potential nonorthogonal local-orbital minimum-basis band-structure scheme. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1743 (1999).

Opahle, I., Koepernik, K. & Eschrig, H. Full-potential band-structure calculation of iron pyrite. Phys. Rev. B 60, 14035 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Koepernik, K., Janson, O., Sun, Y. & van den Brink, J. Symmetry-conserving maximally projected Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 107, 235135 (2023).

Montalti, M., Credi, A., Prodi, L. & Gandolfi, M. T. Handbook of Photochemistry (CRC Press, 2006).

Colpa, J. Diagonalization of the quadratic boson Hamiltonian. Phys. A 93, 327–353 (1978).

Toth, S. & Lake, B. Linear spin wave theory for single-Q incommensurate magnetic structures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 27, 166002 (2015).

Information Systems and Wake Forest University. WFU High Performance Computing Facility. https://hpc.wfu.edu (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank M. Ozerov for many insightful discussions on FePS3 and other materials. This research was funded by the Center for Functional Materials at WFU through a pilot grant, and Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) through the Ralph E. Powe Junior Faculty Enhancement Award to S.M.W. Computations were performed using the Wake Forest University (WFU) High Performance Computing Facility72, a centrally managed computational resource available to WFU researchers including faculty, staff, students, and collaborators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.W. designed the research. R.D. and S.G. performed the numerical computations. S.M.W. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhakal, R., Griffith, S. & Winter, S.M. Hybrid spin-orbit exciton-magnon excitations in FePS3. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 64 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-024-00675-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-024-00675-x

This article is cited by

-

Interplay of vibrational, electronic, and magnetic states in CrSBr

npj Quantum Materials (2026)

-

Steering entanglement through exceptional points in non-hermitian cavity magnomechanics

npj Quantum Materials (2025)

-

Understanding the microscopic origin of the magnetic interactions in CoNb2O6

npj Quantum Materials (2025)

-

Interlayer interaction and Davydov splitting in antiferromagnetic few-layer NiPS3

npj Quantum Materials (2025)

-

Quantum order by disorder is a key to understanding the magnetic phases of BaCo2(AsO4)2

npj Quantum Materials (2025)