Abstract

Nonlinear light-matter interaction at low energy, particularly in the terahertz (THz) frequency range, hosts unique phenomena distinct from the optical excitation with photon energy of a few eV. In cuprate superconductors Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x, the THz nonlinear response is identified via the optical reflectivity change and interpreted as the amplitude mode of the superconducting condensate, namely the Higgs mode [K. Katsumi et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 117001 (2018)]. However, the origin of the THz nonlinearity has been questioned because the pair-breaking process, identified in Raman spectroscopy, can also contribute to it. Here, we reexamined the THz-driven nonequilibrium dynamics in cuprates Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x by comparing it with the Raman susceptibility. In the optical reflectivity change, we found an oscillatory behavior following the squared THz waveform (THz Kerr signal), as well as the relaxation of the quasiparticle excitation. Careful insight into the data revealed that the oscillatory and decaying contributions exhibit different doping dependence. Remarkably, the doping and temperature evolutions of the THz Kerr signal are distinct from those of the Raman susceptibility, which is described by the pair-breaking due to diamagnetic light–matter interaction. These results indicate the importance of the paramagnetic light–matter coupling in the THz Kerr signal in the cuprate superconductors, likely arising from the Higgs mode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light–matter interaction in quantum materials is one of the key aspects to elucidate their properties. In particular, terahertz (THz) frequency range is of great interest as it enables access to rich low-energy excitations in such materials as a consequence of the complex interplay between charge, spin, orbital, and lattice. For instance, in the case of the linear response in dirty-limit BCS superconductors, the real part of the THz optical conductivity shows a reduction in its spectral weight below twice the superconducting (SC) gap 2Δ, which is transferred to the zero-frequency delta-function1.

Recent advances in generating an intense THz pulse give access to the nonlinear light–matter interaction, which can provide information unreachable by linear light–matter coupling2,3. In BCS superconductors, THz nonlinear responses, investigated by pump-probe spectroscopy or third-harmonic generation (THG), were initially ascribed to the amplitude mode of the SC order parameter, referred to as the Higgs mode4,5,6,7,8. This illustrates the unique information obtained by the nonlinear optical spectroscopy, which cannot be accessed by the linear response8. Furthermore, it opens a new avenue toward coherent light control of SC order parameters. However, subsequent theoretical works showed that the THz nonlinear response of a clean BCS superconductor, where only diamagnetic light–matter coupling terms contribute, is actually governed by charge density fluctuations (CDF). The CDF contribution leads to a pair-breaking peak at twice the SC gap and is usually thought to be the dominant contribution to the Raman response, whose BCS non-resonant diamagnetic terms are essentially identical to the THz third-order nonlinear response9. Later, the importance of the paramagnetic light–matter coupling terms in boosting the Higgs contribution to the THz nonlinear response was pointed out in the presence of finite disorder, indicating that the relative hierarchy of the two contributions depends on the disorder level10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. In the specific case of a dirty-limit superconductor like NbN with a relatively high disorder level, the nonlinear response was argued to be dominated by the Higgs mode13. Yet, experimentally disentangling the diamagnetic and paramagnetic contributions to the THz nonlinear signal is challenging as both display the same resonant enhancement when the twice the THz pump frequency matches 2Δ10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

More recently, THz two-dimensional coherent spectroscopy (THz 2DCS) was introduced to single out the nonlinear paramagnetic light–matter coupling of the Higgs mode in NbN18. This also demonstrated that the excitation process in THz nonlinear response can be essentially different from that of the Raman response, which is performed in the optical frequency range of a few eV and is usually assigned to the CDF contribution9,19.

Having gained a deeper understanding of the Higgs mode in conventional superconductors, studies have been expanded to unconventional superconductors. In the case of cuprate superconductors, the observation of the Higgs mode can provide unique insight into their SC properties, including the SC fluctuations20, the interplay between SC and competing orders21, and the coupling of the SC order parameter to lattice or spin excitations. However, the distinction between the Higgs mode and CDF is less clear-cut in the case of cuprate superconductors, which are usually in the clean limit and the diamagnetic terms are therefore expected to play a leading role in the THz nonlinearity14,15. Therefore, although the THz nonlinearity in cuprates has been reported by several experiments and interpreted as the Higgs mode20,21,22,23,24, its origin is still under discussion14,15,25,26,27.

To investigate the nature of the THz nonlinearity in cuprate superconductors, we revisited our THz pump-optical probe (TPOP) spectroscopy in cuprate superconductors Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x (Bi2212), in ref. 22 by comparing it with Raman experiments performed on the same single crystals. In the SC state, we identified the relaxation of the quasiparticle (QP) excitation (decaying signal), as well as the forced oscillation following the squared THz waveform, i.e., the THz Kerr signal, where the refractive index at the probing wavelength at 800 nm is modulated by the THz pump28. Remarkably, the THz Kerr signal displays a markedly different doping dependence from the Raman susceptibility.

We further compare the temperature dependence of the THz Kerr signal with that of the extracted real part of the Raman susceptibility evaluated at the THz pump frequency of 0.7 THz. The extracted Raman susceptibility does not exhibit an increase below the SC transition temperature Tc, in stark contrast to that of the THz Kerr signal, which displays a sharp increase below Tc. These findings lead us to conclude that the THz Kerr and Raman responses in the SC state arise from different light–matter coupling terms: the Raman response is dominated by the CDF contribution from the diamagnetic terms, while the THz Kerr response arises from a different origin.

Results

THz-Kerr signals

A schematic of TPOP spectroscopy is illustrated in Fig. 1a. We measured the THz pump-induced transient reflectivity change at 800 nm (1.55 eV in photon energy), varying the delay time between the pump and the probe pulses (tpp). In Fig. 1b, we present the waveform of the THz pulse (left) and its power spectrum (right), centered at 0.7 THz. The polarization of the THz electric field is along the Cu–O bond of the sample, and that of the probe is parallel or perpendicular to the pump. In the case of Bi2212, whose symmetry belongs to the D4h point group, we obtain the polarization-independent A1g component of the reflectivity change ΔR/R by adding ΔR/R for the probe parallel or perpendicular to the pump22. Similarly, the B1g component is obtained by subtracting ΔR/R for the probe perpendicular to the pump from that for the probe parallel to the pump. We performed TPOP experiments on the Bi2212 families as summarized in Table 1.

a Schematic of the THz pump-optical probe (TPOP) spectroscopy. b Time trace (left) and power spectrum (right) of the THz pump pulse. c–e The A1g and B1g components of the THz pump-induced reflectivity change as a function of the delay time tpp for c UD62, d OP90, and e OD66 at 10 K. The black dashed lines denote the peaks in the THz-pump time trace in (b).

Figure 1c presents the A1g and B1g parts of the THz pump-induced reflectivity change ΔR/R for the selected Bi2212 samples in the SC state at 10 K, adapted from ref. 22. In all the Bi2212 samples, both A1g and B1g parts of ΔR/R display an oscillatory behavior following the two peaks in the THz-pump time trace indicated by the black vertical dashed lines. As reported in ref. 22, the intensity of the oscillatory signal follows the squared THz electric field (E-field), and the third-order nonlinear process is called the THz Kerr signal28. One can also find the relaxation of the QP excitation in ΔR/R, namely the decaying signal. To decompose the contributions of the THz Kerr and decaying signals, we fit ΔR/R with the following model22:

The first, second, and third terms denote the THz Kerr, decaying, and long-lived offset components, respectively (see ref. 22 for details). We note that the first term should be frequency-independent in our off-resonant excitation condition, for which the response is expected to be nearly instantaneous. For this term, we found a small but finite response time, indicating a finite damping rate of the nonlinear response. As a consequence, the B1g components in Fig. 1c–e, which exhibit only the nearly instantaneous response, do not exactly follow the squared waveform of the THz pump \({E}_{{\rm{THz}}}{({t}_{{\rm {pp}}})}^{2}\). To precisely reproduce this delayed response, we convoluted the first term in Eq. (1) with an exponential function29. Figure 2a and b show the fitting results for the A1g and B1g components in OP90 at 10 K. For the B1g component, we set AD = AO = 0 because it does not show any decaying signals. The fit for the B1g component yields a response time τK of 200 fs, which was used for the A1g one. We plot the amplitudes of the fitting parameters as a function of the hole concentration p for the A1g and B1g components in Fig. 2c and d, respectively. For the A1g part, the decaying signal (the orange circles) decreases toward the overdoped regime and switches its sign from positive to negative around p = 0.19. By contrast, the THz Kerr signal (the red circles) also displays a reduction toward overdoping, but does not change its sign. For the B1g part (the blue circles), THz Kerr signal shows an increasing trend toward overdoping.

a and b Fitting for the THz pump-induced reflectivity change of the OP90 sample at 10 K using Eq. (1) for a the A1g and b B1g components. In a, the black dashed curve denotes the fitting curve. The THz Kerr, decaying, and offset components correspond to the three terms in Eq. (1). c and d The amplitude of the THz Kerr and decaying components as a function of the hole concentration p for c the A1g and d B1g components. e and f Temperature dependence of the A1g and B1g THz Kerr signals for e OP90 and f OD82.

To understand the different doping dependence of the three contributions, we express the reflectivity change in terms of the dielectric function as

Here, ε1 and ε2 are the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function in equilibrium at the probing angular frequency ωprobe, and Δε1 and Δε2 are the real and imaginary parts of the pump-induced changes in dielectric function. The pump-induced change in the complex dielectric function Δε can be decomposed into the THz Kerr and the QP contributions as Δε = ΔεKerr + ΔεQP. As discussed below, only the real part of Δε matters in both contributions. Importantly, the coefficient ∂R/∂ε1 at 1.55 eV is positive and does not depend on doping and temperature (see the “Methods” section). In the following, we carefully examine ΔεKerr, which was not discussed in ref. 22. In the “Methods” section, we also discuss ΔεQP to confirm the consistency of our analysis with previous optical pump-probe experiments.

When the pump-photon energy is much smaller than the SC gap energy, the imaginary part of ΔεKerr is negligible compared to the real part22. In this case, we can again focus on the real part of the dielectric function \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1}^{\,\text{Kerr}\,}\), which can be written as22

Here, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, \({\chi }_{1}^{(3)}\) is the real part of the third-order nonlinear susceptibility, which can be decomposed into the A1g and B1g components, and ETHz(ωpump) is the THz E-field at the angular frequency ωpump. One can see that \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1}^{\,\text{Kerr}\,}\) is positive as long as \({\chi }_{1}^{(3)} > 0\). Since ∂R/∂ε1 > 0 at ωprobe = 1.55 eV, the signs of the A1g and B1g components of ΔR from the THz Kerr signals are positive, consistent with the experimental results for the entire doping range of Bi2212 studied.

The distinct doping evolutions of the A1g and B1g THz Kerr signals indicate that their origins are likely different. The THz nonlinear response in cuprate has been studied in theoretical works, showing that in the case of the clean-limit case relevant to cuprate superconductors, the THz nonlinear response is dominated by the diamagnetic light-matter interaction and thus the CDF contribution14,15. This contribution is the one leading to the well-known pair-breaking peak observed in Raman measurements19. If this is the case, one would reasonably expect that the THz Kerr signal displayed the same doping trend as that of the Raman susceptibility. Indeed, the doping evolution of the B1g THz Kerr signal seems to agree with that of the B1g Raman susceptibility and exhibits an increase toward the overdoped regime30. On the contrary, the A1g THz Kerr signal displays completely opposite doping dependence: it increases when reducing the doping, whereas the A1g channel Raman susceptibility is reduced in underdoped samples30,31. The reduction in the B1g and A1g Raman intensity toward underdoping was attributed to the loss of density of states at the anti-nodal region, likely related to the pseudogap opening30,32,33,34. We note that contrary to the B1g channel which is firmly ascribed to the CDF contribution, the exact origin of the A1g channel Raman signal is still controversial25,30,31,35,36,37,38,39. Therefore, it appears difficult to conclude on the origin of the THz Kerr signal in Bi2212 based on its doping evolution alone.

Temperature evolution of the THz Kerr signal and Raman spectroscopy

Having seen the distinct doping evolution of the A1g THz Kerr signal and the Raman susceptibility, we further compare their temperature dependence across Tc. The temperature dependence of the THz Kerr signal for OP90 and OD82 samples is presented in Fig. 2e and f. It displays a steep increase below Tc, indicating its relevance to the SC state. Now turning to the Raman response, Figure 3a and b display the imaginary part of the B1g Raman susceptibility χ2(ω) for OP90 and OD82 samples adopted from refs. 30,33. The B1g Raman susceptibility is well described by the CDF contribution from a d-wave gap within the effective mass approximation19. This approximation is valid in the case of non-resonant Raman scattering, which is confirmed in the case of Bi2212 from the absence of incoming laser wavelength dependence of the Raman spectra in the SC state40. In the following, we focus on the B1g Raman susceptibility as a representative of the CDF response of the cuprates. We note the recent non-equilibrium anti-Stokes Raman measurement claiming the presence of the Higgs mode. The finite Higgs Raman intensity was presumed to arise due to a strongly enhanced out-of-equilibrium population of the Higgs mode41. This does not apply to the equilibrium Raman measurements discussed here. As discussed in the previous section, the THz Kerr signal in the TPOP experiments is approximated as the real part of the third-order nonlinear susceptibility \({\chi }_{1}^{(3)}\). On the other hand, in standard Raman experiments, the imaginary part of the Raman susceptibility χ2(ω) is measured, which is shown in Fig. 3a and b. To evaluate its real counterpart χ1(ω), we perform the Kramers–Kronig transformation to χ2(ω) as

where ωc is a cut-off frequency. Figure 3c and d present the temperature dependence of the real part of the B1g Raman susceptibility at the pump frequency χ1(ω) at ω = ωpump for the OP90 and OD82 samples. For both samples, the real part of the Raman susceptibility χ1 at ω = ωpump is always greater than the imaginary part χ2. We note that χ1 is underestimated as we set a finite cut-off ωc in Eq. (4), reinforcing our assumption that χ2 is negligible compared to χ1. Furthermore, the Raman susceptibility is essentially constant across Tc, whereas the THz Kerr signals in Fig. 2e and f display an increase below Tc. The distinct temperature dependence of the THz Kerr signal and Raman susceptibility further reinforces the idea that their origins are different. It is important to stress that the temperature-independent χ1(ωpump) is fully consistent with the CDF interpretation of the Raman response. For electrons with a finite lifetime, it is known that the static susceptibility extracted in the dynamical limit \({\chi }_{0}^{{\rm {dynamic}}}=\mathop{\lim }\limits_{\omega \to 0}\chi (q=0,\omega )\), as is done when using Eq. (4) and setting ω = 0, is the same as the thermodynamical static susceptibility \({\chi }_{0}^{\rm {{static}}}=\mathop{\lim }\limits_{q\to 0}\chi (q,\omega =0)\)42. The latter quantity is essentially constant across Tc and proportional to the density of states at the Fermi level weighted by the Raman vertex43. The above argument based on static quantities is valid in our case because the THz-pump photon energy of 2.8 meV is much lower than the anti-nodal SC gap energy of 65 meV in the optimally doped Bi2212 sample30,32,33,44. Note that the equivalence between the static and the dynamical limits no longer holds for electrons with an infinite lifetime42. In that case, the uniform (q = 0) diamagnetic CDF Raman and THz nonlinear responses are zero at low energy in the normal state because of the momentum conservation on the creation of intraband electron–hole pairs with zero momenta19. This explains why the previous calculations performed without any lifetime effects found an onset of the CDF contribution below Tc22.

a and b The imaginary part of the B1g Raman susceptibility χ2 at selected temperatures for a OP90 and b OD82. c and d Temperature dependence of the real part of the B1g Raman susceptibility (χ1, blue squares) evaluated using the Kramers–Kronig relation for c OP90 and d OD82. The imaginary part χ2 is also shown by green squares. The black dashed vertical lines denote Tc.

The comparison of the TPOP and Raman results unambiguously demonstrates that the THz Kerr signal in TPOP is distinct from the diamagnetic CDF contribution. This is consistent with the polarization dependence of the diamagnetic CDF contribution theoretically evaluated for the THz Kerr response in ref. 22. There, the theoretical ratio of the anisotropic term over the isotropic one is 10, while the ratio in the experiments is always <1.

Discussion

In light of the previous observations, we now discuss the origin of the THz Kerr signal. The possible relevant contributions for the A1g THz Kerr response are the Higgs mode and the CDF. In cuprates, the Higgs and CDF contributions to THz THG signal were examined assuming that the pump frequency Ω is set to zero15. There, the paramagnetic CDF response was found to consist of an A1g isotropic contribution with a significant polarization dependence due to a B2g component. As a result, the sum of the diamagnetic and paramagnetic CDF contributions was shown to reproduce the isotropic response observed in the experiments because their respective polarization dependencies cancel.

On the other hand, the comparison with the Raman measurements, which display completely different temperature and doping dependence as indicated in the previous section, suggests that diamagnetic CDF does not contribute significantly to the THz Kerr signal. Thus, we are led to conclude that the CDF contribution to the THz Kerr signal should arise dominantly from the paramagnetic terms and therefore should show a prominent polarization dependence. In the THz Kerr experiments, the anisotropic B1g THz Kerr signal over isotropic A1g one is at most 0.1 in the underdoped samples. Therefore, the nearly isotropic character of the THz Kerr response observed in the underdoped region cannot be easily ascribed to the paramagnetic CDF. Accordingly, the A1g THz Kerr response is more likely attributed to the paramagnetic Higgs-mode contribution, at least in the underdoped side of the Bi2212 samples. We note that the above argument is based on the THz THG calculations performed in ref. 15. The THz Kerr response is distinct from the THG one because the probing photon energy is different. It has been argued that for the THz Kerr effect, the paramagnetic term can be less efficient15. Further theoretical work is needed to clarify to what extent THz THG and THz Kerr differ.

Finally, we discuss the possible scenarios for the sub-dominant B1g THz Kerr signal. From the discussion in ref. 22, the Higgs-mode contribution of the THz Kerr signal appears only in the A1g channel, indicating that the origin of the B1g THz Kerr signal is something else. One possibility is that the B1g THz Kerr signal arises from CDF. According to ref. 15, the diamagnetic CDF exhibits the B1g response, while the paramagnetic one is the B2g response. Although its doping evolution is consistent with that of the B1g Raman susceptibility associated with the diamagnetic CDF, the temperature dependence is completely different, casting doubt on this interpretation.

Another possible origin is a collective mode associated with nematicity, as proposed in a previous TPOP experiment in an iron-based superconductor45. A recent theoretical study proposed that close to or even inside a symmetry-lowered nematic phase, a new nematic collective mode with B1g symmetry can emerge below the Higgs mode energy in the presence of competing s- and d-wave SC instabilities46. It is worth mentioning that the signatures of the significant nematic fluctuations and/or order have been reported in Bi2212 by Raman spectroscopy47, elasto-resistance measurement48, and angle-resolved photo emission spectroscopy49. In those studies, the nematic susceptibility is enhanced toward overdoping close to p = 0.22. The origin of the nematicity could be tied to a van Hove singularity47 or related to the pseudogap48. While we cannot decipher the above scenarios at this stage, the comparison between Raman and THz Kerr experiments suggests that the corresponding B1g signals have likely different origins.

In summary, we reexamined the THz nonlinear response in the Bi2212 families by TPOP spectroscopy in ref. 22. Careful analysis of the THz Kerr signal as a function of hole concentration revealed that it increases toward overdoping, contrary to the doping evolution of the Raman susceptibility, which probes the diamagnetic density-density correlation led by the pair breaking. The temperature dependence of the Raman susceptibility is evaluated at THz pump-photon energy, and shows no temperature dependence, in stark contrast to the THz Kerr signal enhanced below Tc. These findings lead us to conclude that the THz Kerr signal is not consistent with the diamagnetic light–matter interaction of the pair breaking, and likely arises from the paramagnetic coupling of the Higgs mode.

Methods

Samples

The Bi2212 single crystals were grown by the floating-zone method. The SC transition temperatures Tc are evaluated by the magnetic susceptibility measurement using a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID). The hole concentrations (p) of the samples are determined from Tc by Presland–Tallon’s equation50. The samples’ Tc and p are summarized in Table 1.

Terahertz pump-optical reflectivity probe (TPOP) spectroscopy

For the TPOP experiments, the output of a regenerative amplified Ti:sapphire laser with the center wavelength at 800 nm, pulse duration of 100 fs, pulse energy of 4 mJ, and repetition rate of 1 kHz was split into two beams. One is for generating the THz-pump pulse, and the other is for the optical probe pulse. To generate an intense single-cycle THz pulse, we utilized the tilted-pulse-front technique with a LiNbO3 crystal51 combined with the tight focusing method52. We evaluated the THz-pump E-field using electro-optic sampling in a 380-μm GaP (110) crystal placed inside the cryostat. The wave form and power spectrum of the THz-pump pulse are represented in Fig. 1b. The TPOP experiments were performed in the reflection geometry, with the normal incidence of the pump and probe beams.

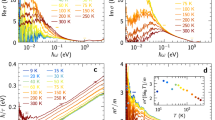

Evaluation of ∂R/∂ε 1

Here, we show that the coefficient ∂R/∂ε1(ω) in Eq. (2) does not depend on the doping. For simplicity, we omit the variable ω from the derivatives and equations. The derivative ∂R/∂ε1 can be expressed using the complex refractive index n(ω) = n1(ω) + in2(ω) as

First, since the reflectivity is related to the complex refractive index n(ω) as R(ω) = ∣(1−n(ω))/(1 + n(ω))∣2 53, the derivatives of ∂R/∂n1 and ∂R/∂n2 are written as

Next, we consider the derivatives of ∂n1/∂ε1 and ∂n2/∂ε1. From the relation ε(ω) = n(ω)2, the complex refractive index n is expressed in terms of ε as

Thus, we obtain the expressions for ∂n1/∂ε1 and ∂n2/∂ε1 as

By plugging Eqs. (6)–(8) into Eq. (5), we can calculate ∂R/∂ε1 if the real part of the dielectric function ε1(ω) and its imaginary counterpart ε2(ω) = ε0σ1(ω)/ω (σ1(ω) is the real part of the optical conductivity) are provided. Figure 4a and b present the real parts of the dielectric function ε1(ω) and optical conductivity σ1(ω), respectively. The data of the UD66 and OP88 samples in the SC state are taken from ref. 54, and those of the OD77 and OD67 samples are adopted from ref. 55. Importantly, at the probing photon energy of 1.55 eV (800 nm in wavelength), σ1(ω) coincides for all the samples. Thus, it is reasonable to consider that ∂R/∂ε1 is independent of doping. Using these spectra, we obtain ∂R/∂ε1 for UD66 as shown by the blue dashed curve in Fig. 4c. At 1.55 eV, ∂R/∂ε1 is positive. To confirm that ∂R/∂ε1 does not depend on doping, we also compute ∂R/∂ε1 for OP88, showing an excellent agreement with that of UD66 in Fig. 4c. We further evaluated the temperature dependence of ∂R/∂ε1 for OP88 at 1.55 eV using the data of ε1(ω) and ε2(ω) from ref. 56. The obtained ∂R/∂ε1 is plotted as a function of temperature in Fig. 4d, and does not depend on temperature, even across Tc. These results guarantee that we can ignore the doping and temperature dependences of ∂R/∂ε1 at 1.55 eV.

a Real parts of the dielectric function ε1 and b optical conductivity σ1. The data for UD66 at 20 K and OP88 at 15 K are adopted from ref. 54, and those for OD77 and OD67 at 40 K are taken from ref. 55. c The derivative ∂R/∂ε1 for UD66 at 20 K (blue dashed curve) and OP88 at 15 K (green solid curve). The black vertical arrows denote the probe-photon energy of 1.55 eV in TPOP experiments. d Temperature dependence of ∂R/∂ε1 for OP88 calculated using the values of ε1 and ε2 from ref. 56. The black dashed vertical line shows Tc = 88 K.

Quasiparticle decaying signal

Here, we examine the QP contribution ΔεQP to confirm the internal consistency of the analysis. In the previous optical pump-optical probe experiments in Bi2Sr2Ca1−yDyyCu2O8+x samples, the QP excitation \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1}^{\,\text{QP}\,}\) is identified, and the sign change of ΔR/R depending on doping is also reported57,58,59. Although there was a debate on the mechanism of ΔR/R probed at the optical photon energy of 1.55 eV57,60,61,62, the sign of ΔR/R can be understood with a model assuming that ΔR/R at 1.55 eV comes from the pump-induced spectral weight transfer in the real part of the dielectric function57,60. In this model, the sign of \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1}^{\,\text{QP}\,}\) depends on the relative order of the probing angular frequency ωprobe and the maximum angular frequency ωmax, where the condensate spectral weight reappears after pumping. In the case of ωprobe ≫ ωmax, we can approximate Δε1 using the Kramers–Kronig relation as

where Δσ1 is the spectral weight of the real part of the optical conductivity σ1 removed from the condensate δ-function by the pumping. This limit holds if the condensate spectral weight at the δ-function is distributed to low frequencies, giving Δσ1 > 0 and thus, \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1}^{\,\text{QP}\,} < 0\) according to Eq. (9). Since the sign of the derivative ∂R/∂ε1 at ωprobe = 1.55 eV is positive in the case of Bi2212 as shown in Fig. 4c, ΔR at 1.55 eV is negative. This explains the negative reflectivity change in the overdoped samples in the optical-pump-induced QP excitations. In the case of underdoped samples, however, the in-plane condensate spectral weight shifts to high frequencies, i.e., ωprobe < ωmax54,55,56,63, resulting in \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1}^{\,\text{QP}\,} > 0\) and ΔR > 0 at 1.55 eV. It is noteworthy that even though our pump-photon energy of THz pulse around 2.8 meV is much smaller than that of 1.55 eV in ref. 57, the sign change of ΔR occurs around the hole concentration of p = 0.19, similar to the optical pumping case, indicating that the THz pump-induced change in the probing photon energy due to the partial destruction of the SC state is consistent with that of the high-energy 1.55 eV pump. In other words, the modulation of the optical property at probe photon energy of 1.55 eV does not depend on the pump wavelength.

Raman spectroscopy

The Raman spectra of Bi2212 were measured using the triple grating spectrometer equipped with a nitrogen-cooled CCD camera. The excitation laser wavelength is at 532 nm from a diode-pumped solid-state laser. To calculate the imaginary part of the Raman response function χ2(ω), we corrected the raw Raman spectra by the Bose factor64.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors (K.K., Y.G., and R.S.) upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All the numerical codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors (K.K., Y.G., and R.S.) upon reasonable request.

References

Tinkham, M. Introduction to superconductivity. Second Edition, Dover Books on Physics (Courier Corporation, 2004).

Kampfrath, T., Tanaka, K. & Nelson, K. A. Resonant and nonresonant control over matter and light by intense terahertz transients. Nat. Photon. 7, 680–690 (2013).

Nicoletti, D. & Cavalleri, A. Nonlinear light–matter interaction at terahertz frequencies. Adv. Opt. Photonics 8, 401–464 (2016).

Matsunaga, R. et al. Higgs amplitude mode in the BCS superconductors Nb1-xTixN induced by terahertz pulse excitation. Phys. Rev. Lett 111, 057002 (2013).

Matsunaga, R. et al. Light-induced collective pseudospin precession resonating with Higgs mode in a superconductor. Science 345, 1145–9 (2014).

Tsuji, N. & Aoki, H. Theory of Anderson pseudospin resonance with Higgs mode in superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064508–064508 (2015).

Matsunaga, R. et al. Polarization-resolved terahertz third-harmonic generation in a single-crystal superconductor NbN: dominance of the Higgs mode beyond the BCS approximation. Phys. Rev. B 96, 020505(R) (2017).

Shimano, R. & Tsuji, N. Higgs mode in superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 103–103 (2020).

Cea, T., Castellani, C. & Benfatto, L. Nonlinear optical effects and third-harmonic generation in superconductors: Cooper pairs versus Higgs mode contribution. Phys. Rev. B 93, 180507(R)–180507(R) (2016).

Jujo, T. Quasiclassical theory on third-harmonic generation in conventional superconductors with paramagnetic impurities. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 87, 024704 (2018).

Murotani, Y. & Shimano, R. Nonlinear optical response of collective modes in multiband superconductors assisted by nonmagnetic impurities. Phys. Rev. B 99, 224510 (2019).

Silaev, M. Nonlinear electromagnetic response and Higgs-mode excitation in BCS superconductors with impurities. Phys. Rev. B 99, 224511 (2019).

Tsuji, N. & Nomura, Y. Higgs-mode resonance in third harmonic generation in NbN superconductors: multiband electron–phonon coupling, impurity scattering, and polarization-angle dependence. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043029 (2020).

Seibold, G., Udina, M., Castellani, C. & Benfatto, L. Third harmonic generation from collective modes in disordered superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014512 (2021).

Udina, M. et al. The non-linear optical response in cuprates: predominance of the BCS response over the Higgs mode. Faraday Discuss. 237, 168–185 (2022).

Fiore, J., Udina, M., Marciani, M., Seibold, G. & Benfatto, L. Contribution of collective excitations to third harmonic generation in two-band superconductors: the case of MgB2. Phys. Rev. B 106, 094515 (2022).

Seibold, G. On the evaluation of higher harmonic current responses for high-field spectroscopies in disordered superconductors. Condens. Matter 8, 95 (2023).

Katsumi, K. et al. Revealing novel aspects of light-matter coupling by terahertz two-dimensional coherent spectroscopy: the case of the amplitude mode in superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 256903 (2024).

Devereaux, T. P. & Hackl, R. Inelastic light scattering from correlated electrons. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 175–233 (2007).

Katsumi, K., Li, Z. Z., Raffy, H., Gallais, Y. & Shimano, R. Superconducting fluctuations probed by the Higgs mode in Bi2Sr2 CaCu2O8.xÿthin films. Phys. Rev. B 102, 054510 (2020).

Chu, H. et al. Fano interference between collective modes in cuprate high-Tc superconductors. Nat. Commun. 14, 1343 (2023).

Katsumi, K. et al. Higgs mode in the d-wave superconductor Bi2Sr2 CaCu2O8.x driven by an intense terahertz pulse. Phys. Rev. Lett 120, 117001 (2018).

Chu, H. et al. Phase-resolved higgs response in superconducting cuprates. Nat. Commun 11, 1793 (2020).

Yuan, J. et al. Dynamical interplay between superconductivity and pseudogap in cuprates as revealed by terahertz third-harmonic generation spectroscopy. Sci. Adv. 10, eadg9211 (2024).

Puviani, M., Haenel, R. & Manske, D. Quench-drive spectroscopy and high-harmonic generation in BCS superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 107, 094501 (2023).

Benfatto, L., Castellani, C. & Cea, T. Comment on “calculation of an enhanced A1g symmetry mode induced by Higgs oscillations in the Raman spectrum of high-temperature cuprate superconductors”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 199701 (2022).

Benfatto, L., Castellani, C. & Seibold, G. Linear and nonlinear current response in disordered d-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 108, 134508 (2023).

Hoffmann, M. C., Brandt, N. C., Hwang, H. Y., Yeh, K.-L. & Nelson, K. A. Terahertz Kerr effect. Appl. Phys. Lett 95, 231105 (2009).

Yada, H., Miyamoto, T. & Okamoto, H. Terahertz-field-driven sub-picosecond optical switching enabled by large third-order optical nonlinearity in a one-dimensional Mott insulator. Appl. Phys. Lett 102, 091104 (2013).

Benhabib, S. et al. Three energy scales in the superconducting state of hole-doped cuprates detected by electronic Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. B 92, 134502 (2015).

Le Tacon, M., Sacuto, A. & Colson, D. Two distinct electronic contributions in the fully symmetric Raman response of high-Tc cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 71, 100504 (2005).

Blanc, S. et al. Quantitative Raman measurement of the evolution of the Cooper-pair density with doping in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 80, 140502 (2009).

Blanc, S. et al. Loss of antinodal coherence with a single d-wave superconducting gap leads to two energy scales for underdoped cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 144516 (2010).

Sacuto, A. et al. Electronic Raman scattering in copper oxide superconductors: Understanding the phase diagram. C. R. Phys. 12, 480–501 (2011).

Cooper, S. et al. Gap anisotropy and phonon self-energy effects in single-crystal YBa2Cu3O7−δ. Phys. Rev. B 38, 11934 (1988).

Staufer, T., Nemetschek, R., Hackl, R., Müller, P. & Veith, H. Investigation of the superconducting order parameter in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8 single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 1069 (1992).

Gallais, Y., Sacuto, A. & Colson, D. Resonant Raman scattering in mercurate single crystals. Physica C: Superconductivity 408, 785–788 (2004).

Venturini, F., Michelucci, U., Devereaux, T. P. & Kampf, A. P. Collective spin fluctuation mode and Raman scattering in superconducting cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 62, 15204–15207 (2000).

Montiel, X. et al. η collective mode as A1g Raman resonance in cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 93, 024515 (2016).

Venturini, F. et al. Doping dependence of the electronic Raman spectra in cuprates. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 63, 2345–2348 (2002).

Glier, T. E. et al. Direct observation of the Higgs mode in a superconductor by non-equilibrium Raman scattering. Nat. Commu 16, 7027 (2025).

Gallais, Y. & Paul, I. Charge nematicity and electronic Raman scattering in iron-based superconductors. C. R. Phys. 17, 113–139 (2016).

Labat, D., Kotetes, P., Andersen, B. M. & Paul, I. Variation of shear moduli across superconducting phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 101, 144502 (2020).

Anzai, H. et al. Relation between the nodal and antinodal gap and critical temperature in superconducting Bi2212. Nat. Commun. 4, 1815 (2013).

Grasset, R. et al. Terahertz pulse-driven collective mode in the nematic superconducting state of Ba1–xKxFe2As2. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 4 (2022).

Müller, M. A., Volkov, P. A., Paul, I. & Eremin, I. M. Interplay between nematicity and Bardasis–Schrieffer modes in the short-time dynamics of unconventional superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 103, 024519 (2021).

Auvray, N. et al. Nematic fluctuations in the cuprate superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Nat. Commun. 10, 5209 (2019).

Ishida, K. et al. Divergent nematic susceptibility near the pseudogap critical point in a cuprate superconductor. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 89, 064707 (2020).

Nakata, S. et al. Nematicity in a cuprate superconductor revealed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy under uniaxial strain. npj Quantum Mater. 6, 86 (2021).

Presland, M., Tallon, J., Buckley, R., Liu, R. & Flower, N. General trends in oxygen stoichiometry effects on tc in bi and tl superconductors. Physica C: Superconductivity 176, 95–105 (1991).

Hebling, J., Almasi, G., Kozma, I. & Kuhl, J. Velocity matching by pulse front tilting for large area tHz-pulse generation. Opt. Express 10, 1161 (2002).

Watanabe, S., Minami, N. & Shimano, R. Intense terahertz pulse induced exciton generation in carbon nanotubes. Opt. Express 19, 1528–1538 (2011).

Dressel, M. & Grüner, G. Electrodynamics of Solids: Optical Properties of Electrons in Matter (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Molegraaf, H., Presura, C., Van Der Marel, D., Kes, P. & Li, M. Superconductivity-induced transfer of in-plane spectral weight in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Science 295, 2239–2241 (2002).

Carbone, F. et al. Doping dependence of the redistribution of optical spectral weight in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. B 74, 064510 (2006).

Kuzmenko, A., Molegraaf, H., Carbone, F. & Van Der Marel, D. Temperature-modulation analysis of superconductivity-induced transfer of in-plane spectral weight in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8. Phys. Rev. B 72, 144503 (2005).

Gedik, N. et al. Abrupt transition in quasiparticle dynamics at optimal doping in a cuprate superconductor system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 117005 (2005).

Giannetti, C. et al. Revealing the high-energy electronic excitations underlying the onset of high-temperature superconductivity in cuprates. Nat. Commun. 2, 353 (2011).

Giannetti, C. et al. Ultrafast optical spectroscopy of strongly correlated materials and high-temperature superconductors: a non-equilibrium approach. Adv. Phys. 65, 58–238 (2016).

Segre, G. P. et al. Photoinduced changes of reflectivity in single crystals of YBa2Cu3O6.5 (ortho II). Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 137001 (2002).

Demsar, J., Averitt, R. D., Kabanov, V. V. & Mihailovic, D. Comment on “photoinduced changes of reflectivity in single crystals of YBa2Cu3O6.5 (ortho II)”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 169701 (2003).

Gedik, N., Orenstein, J., Liang, R., Bonn, D. A. & Hardy, W. N. Gedik et al. reply. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 169702 (2003).

Rübhausen, M., Gozar, A., Klein, M., Guptasarma, P. & Hinks, D. Superconductivity-induced optical changes for energies of 100 δ in the cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 63, 224514 (2001).

Hayes, W. & Loudon, R. Scattering of Light by Crystals. Dover Books on Physics (Courier Corporation, 2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Indranil Paul for fruitful discussions. This project was partly supported by JST CREST (Grant No. JP- MJCR19T3), Japan. Y.G. acknowldges funding from ANR Grants NEPTUN and SUPER2DTMD. K.K. acknowledges funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation (DMR-2442520).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K. analyzed the data of the THz pump-optical probe experiments. Y.G. analyzed the Raman data. K.K. prepared all the figures. Y.G. and R.S. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Katsumi, K., Gallais, Y. & Shimano, R. Distinct terahertz nonlinear and Raman responses in cuprate superconductors Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 91 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00807-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00807-x