Abstract

Stress is a key factor in psychotic relapse, and mindfulness offers stress resilience and well-being benefits. This study examined the effects of mindfulness-based intervention for psychosis (MBI-p) in preventing relapse at 1 year among patients with remitted psychosis in Hong Kong. MBI-p is a newly developed manual-based mindfulness protocol and was tested to have improved well-being and clinical outcomes in a pilot study with remitted psychosis patients. In this multisite, single-blind, 1-year randomized controlled trial (RCT), 152 fully remitted patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or non-affective psychosis were randomized to receive either a 7-week MBI-p or a 7-week psychoeducation program. Outcomes were assessed before and after the intervention, and then monthly for one year. Relapse rate and severity at one year were the primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes included psychopathology, functioning, mindfulness, and psychosocial factors such as stress and expressed emotions. No significant differences were found in the rate and severity of relapse between the MBI-p and psychoeducation groups in either intention-to-treat or per-protocol analyses. While MBI-p improved observation and non-reactivity to the inner experience of mindfulness, psychoeducation was found to benefit functioning and psychosocial functioning more than MBI-p. This is the first RCT to test MBI-p’s effectiveness in preventing relapse among patients with remitted psychosis in Hong Kong. We postulate that the lack of significance is due to the heightened effectiveness of psychoeducation in coping with stress during the pandemic and the multifactorial causes leading to relapse. This suggests the possibility of combining these two interventions to improve their efficacy. Trial registration: NCT04060498.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preventing relapse after stabilizing the first episode of psychosis is crucial. Psychotic symptom recurrence, such as delusions and hallucinations, is distressing and costly1, with some relapses leading to treatment resistance2. Although antipsychotic medication can be effective, not all patients can avoid relapse. Even among those who continue their antipsychotic treatment, the relapse rate remains at 41%3. Interest in non-pharmacological treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), is growing. Multimodal CBT for patients, families, and group CBT have been effective and have successfully reduced relapse4,5. However, delivering CBT can be challenging in resource-limited settings because it needs specialized therapists. Family interventions have also shown a 20% reduction in relapse rates in schizophrenia6; nevertheless, routine use depends on varying family involvement and commitment.

Stress significantly affects psychosis relapse, as evidenced by prospective and retrospective studies linking life events, such as environmental changes and unemployment, to relapse prediction in schizophrenia7,8,9,10,11. These studies show that such stressful events tend to cluster in the two to four weeks immediately preceding relapse. Expressed emotion, particularly “carers’ critical comments,” emerged as a significant predictor of relapse12,13,14. The stress experienced by patients from life events or critical comments underscores its pivotal role in precipitating psychotic relapse, suggesting that interventions targeting stress modulation may aid in relapse prevention. Meanwhile, mindfulness is the practice of being present without judgment, often cultivated through meditation15. It has been linked to improved well-being16, and is recognized as a valuable psychological intervention, known as the third wave after behavioral and cognitive interventions. Recent meta-analyses highlight its effectiveness in alleviating various psychiatric symptoms such as stress, anxiety, mood disorders, and eating disorders17,18. Mindfulness has also shown promise in reducing both daily and clinically relevant stresses in various populations19,20,21,22. Therefore, the exploration of mindfulness intervention that modulates stress may be relevant to relapse prevention in psychosis.

Mindfulness has gained popularity as a non-pharmacological treatment for psychosis. Chadwick23 developed Person-Based Cognitive Therapy (PBCT) by combining Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)24 and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)25. Preliminary studies26,27 and randomized controlled trials (RCTs)28,29,30 suggest that PBCT helps patients respond mindfully to psychotic symptoms, reduces hospitalizations, and improves functioning. However, these protocols are relatively complicated and require intensive training. Therefore, we aimed to test a simplified, manual-based mindfulness protocol—the mindfulness-based intervention for psychosis (MBI-p)31. MBI-p focuses on simplicity for facilitators and patients and uses acceptance and embracing attitudes for fear and sadness. Tong et al.31 developed the protocol using a systematic approach, drawing from multiple sources such as MBSR24, the works of Thich Nhat Hanh32, and Rezek33. The content, number, and duration of the sessions were refined through three pilot trials before finalization. The ultimate aim is to help patients achieve a greater sense of peace and calm and facilitate managing everyday stress and conflicts (for more detailed information on the content and development of the manual and protocol, see Tong et al.31). The pilot study involving 14 patients with remitted schizophrenia revealed that after seven weeks of MBI-p, the severity of psychotic and depressive symptoms and the mental component of life quality improved31. Patients provided positive feedback and experienced positive changes after MBI-p training. Additionally, a meta-analytic review investigating the efficacy of mindfulness meditation in Chinese patients with psychosis found that it improved their mindfulness levels with improvements in well-being and clinical outcomes34.

Given the significant improvement of well-being in the pilot study, we aim to further test the long-term impact and efficacy on relapse prevention of MBI-p. To date, only a few studies have explored the long-term effects of mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) and its role in relapse prevention in remitted psychosis patients specifically in Chinese population34. Longitudinal studies, with follow-up periods ranging from 6 months to 24 months, found significant impact of MBI on improving clinical symptoms for early psychosis, but remission status of the sample is unknown, and the sample is likely to have a mixture of active and remitted patients35,36,37. Most importantly, they tended to measure overall clinical outcome instead of relapse. Meanwhile, only one study has specifically focused on relapse rate and found that MBI is significantly better than treatment as usual (TAU) at post-intervention38. Yet, no longer follow-up was available, and definition of relapse was unclear. Despite the success in soothing clinical symptoms of active psychosis, MBI’s long term impacts and efficacy in preventing relapse remains uncertain.

In this study, we primarily examined whether MBI-p could reduce relapse after one year. We then investigated whether MBI-p could reduce stress and depressive symptoms and improve functioning and life quality at post-intervention and one-year follow-up. One year was chosen as the study duration because previous research indicates that significant changes can be observed within a minimum of six months37. Additionally, it provides sufficient time for relapse to be detected, as demonstrated by naturalistic studies examining relapse rates following first-episode psychosis (FEP) in Hong Kong39,40.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was a single-blind, multisite RCT on MBI’s effectiveness in preventing relapse in patients with remitted psychosis. Recruitment took place between October 2019 and May 2023. In total, 152 eligible patients were consecutively recruited from two general adult outpatient clinics and two Early Assessment Services for Young People with Psychosis (EASY) outpatient psychiatric clinics, located at Queen Mary Hospital and Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital in Hong Kong. EASY provides specialized psychiatric care for young individuals with FEP for the first three years, with extended follow-up when necessary, covering approximately seven million people in Hong Kong. As a result, the sample includes not only early psychosis cases but also a mix of patients with varying durations of illness.

Recruited patients were randomized to receive either a 7-week MBI-p or a 7-week psychoeducation program. This study was reported according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating site and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04060498) before trial commencement. All participants provided written informed consent.

The study comprised the following time points: baseline (before intervention), after the 7-week intervention, and monthly for the remaining one year following intervention. At each time point, participants completed clinical, cognitive, and psychosocial assessments via either Zoom or face-to-face interviews. Relapse was assessed during the intervention and monthly during the one-year follow-up period. Patients were excluded if they relapsed during the study.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age 18–55 years; (2) full symptomatic remission for at least six months (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale: delusion ≤2, conceptual disorganization ≤3, hallucination ≤2, suspiciousness ≤4, unusual thought content ≤3); and (3) sufficient proficiency in Chinese to understand verbal instructions and provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) known diagnosis of intellectual disability, (2) organic brain disorder, (3) current or previous use of illicit drugs, (4) substance-induced psychosis or alcohol intake in excess of five standard units per day, and (5) practice of mindfulness and meditation exercises more than twice a week over the past month.

Sample size

Naturalistic studies in Hong Kong report relapse rates of 16–20% within the first year and 16–40% within the first three years of FEP39,40. Additionally, the only study comparing relapse rates between TAU and MBI found a relapse rate of 13.3% in the intervention group over one month38. Based on these findings, the proposed sample size was 144 patients (72 per treatment group), estimated on a power of 80% and a 0.05 alpha to detect 1-year relapse rates of 15% in the mindfulness group and 35% in the psychoeducation group. Considering a 5% dropout rate, the estimated sample size was 152 patients (76 per treatment group).

Randomization and blinding

Patients were individually randomized into one of two parallel groups: 7-week MBI-p and 7-week psychoeducation. The investigator generated a randomization sequence using a computer with a fixed block size of four without stratification at an intervention-to-control ratio of 1:1. The investigator does not participate in any data obtaining or analysis to prevent bias. The first project staff enrolled patients at psychiatric clinics, and the investigator conducted randomization. During randomization, each patient was consecutively assigned a unique Project ID and treatment arm according to the randomization list. In this single-blind study, investigators, patients, and the first project staff were aware of the treatment arms. However, all subsequent baseline and monthly outcome assessments were conducted by a second-project staff member blinded to the randomization of the treatment and block size.

Intervention

As some patients were recruited from the EASY outpatient clinics, these patients underwent the EASY early intervention. EASY is a 3-year service targeting at those who have experienced their first episode of psychosis in Hong Kong. Specialized multidisciplinary mental health teams offered phase-specific interventions focusing on intensive case management and promoting recovery and functional improvement. EASY’s reach extends through a robust media campaign and screening hotline system41. While the other patients did not receive the EASY interventions, we did not document any additional psychological interventions received by these patients.

Mindfulness intervention group

The mindfulness group underwent MBI-p for seven weeks. MBI-p, a low-intensity protocol-based mindfulness program, aims to enhance patient peace, calmness, and stress management (refer to Tong et al.’s pilot study31 for details). Our facilitators were master’s level psychology graduates trained by two investigators (Tong and Lin). Seven 1.5-hour online group sessions were conducted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, covering engagement, mindfulness practices, daily life applications, and consolidation of learning. Facilitators used adaptations such as mindful outdoor-walking audio for online sessions.

Mindfulness practice encourages participants to respond with clarity to stress reactions and let go of clinging to emotions, thus, fostering a decentered awareness. The program addressed nonjudgment by guiding participants to accept judgments as part of themselves, thereby enhancing stress reactivity through desensitization. Group discussions involved reflection on coping reactions through Socratic discussions.

To support mindfulness practice beyond the sessions, participants received information on mindfulness benefits and a WhatsApp booklet for recording their practices and changes after each session. Moreover, a link to a 3-to-9-min audio of daily mindfulness meditations was sent after every session. Weekly sessions included participants sharing their practice experiences, and monthly booster messages on WhatsApp served as reminders of post-intervention self-practice.

Psychoeducation group

Each psychoeducation session lasted 1.5 h and was held once a week for seven weeks. It included topics on psychosis’ signs and symptoms, etiology of psychosis, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment, healthy living tips such as stress management and exercise, and communication skills. Like the MBI group, our facilitators were master’s-level psychology graduates who had been trained by our investigators. They were also encouraged to engage with participants during each session.

Outcome assessments

Primary outcome

The primary relapse outcome was the presence of all the following conditions for at least one week: (1) an increase in at least one of the following Positive & Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)42 items (delusion, hallucinatory behavior) to a score of ≥3; (conceptual disorganization, unusual thought content) to a score of ≥4; (suspiciousness) to a score of ≥5; (2) Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Severity of Illness43 scale rated ≥3; and (3) CGI Improvement scale rated ≥5. A binary relapse variable was created to represent whether the patient experienced relapse during the follow-up period. Furthermore, continuous variables were also created for individual relapse item scores (e.g., PANSS delusion, PANSS hallucinatory behavior, and PANSS conceptual disorganization). Relapse was assessed before (baseline) and after seven weeks of intervention; thereafter, monthly until one-year post-intervention. Patients experiencing a relapse at any month during the one-year follow-up period signified study termination.

Secondary outcomes

Basic demographic information, including age, sex, years of education, employment status, duration of untreated psychosis, and diagnosis, was obtained at baseline. Psychopathology, functioning, cognitive functioning, psychosocial well-being, and mindfulness were measured before and after intervention; thereafter, monthly for one year.

PANSS measured positive and negative symptoms. The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS)44 measured depressive symptoms, the Modified Medication Adherence Rating Scale45 measured treatment adherence, and the List of Threatening Experiences46 assessed stressful life events. Functioning was measured using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale47, Role-Functioning Scale48, and Social Functioning Scale49, while life quality was measured using the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey50. Psychosocial factors, such as expressed emotion, resilience, and perceived risk of relapse, were measured using the Expressed Emotion Scale51, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale -10 items52, and Perceived Recovery Inventory53. Neurocognitive performance was assessed using the visual pattern test and letter-number span. Mindfulness was measured using the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)54. Scale details are provided in Supplementary List 1.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM® SPSS® version 28.0.1.0. All enrolled participants were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis of relapse prevention at one year. We performed a per-protocol (PP) sensitivity analysis on patients who had completed all seven sessions of either intervention. To explore the predictive nature of the intervention group (MBI-p vs. psychoeducation) for relapse at the one-year post-intervention mark, logistic regression was used for the categorical outcome variable (relapsed vs. no relapse), whereas linear regression determined the continuous outcome variables (e.g., individual relapse item score). Age was included as a covariate in the regression analysis because it showed marginal significance in the preliminary analysis when comparing the demographic information between the two groups. The relapse status of patients who dropped out before the intervention (n= 20) was assessed using the Clinical Management System (CMS). Relapse was defined as the deterioration of symptoms meeting the relapse criteria within one year of their baseline assessment date, as documented in their CMS case notes.

A linear mixed-effects model (LMM) analyzed the secondary outcomes (e.g., psychopathology, functioning, cognitive functioning, and life quality). We compared baseline data with post-intervention (i.e., short-term impacts) and with one-year follow-up outcomes (long-term impacts). This analysis adopted the ITT approach enrolling all participants in this study, regardless of their dropout or relapse status. Data were collected from patients who had dropped out during the study. LMM assessed the interaction effect of interventions (MBI-p vs. psychoeducation) and time (baseline vs. post-intervention or baseline vs. one-year follow-up), controlling for age. For all analyses, a two-sided p-value was calculated and a value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Recruitment outcome

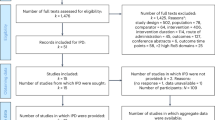

Of 152 participants, 77 were in the MBI-p and 75 in the psychoeducation group. Ten patients withdrew before intervention in both interventions. During the intervention, three participants withdrew from MBI-p, one relapsed, and two withdrew from psychoeducation. During the one-year follow-up, 10 patients relapsed, 12 withdrew from MBI-p, 6 relapsed, and 17 withdrew from the psychoeducation program (Fig. 1).

Enrollment and outcomes. aThe relapse status of patients who dropped out before the intervention (n = 20) was assessed using the Clinical Management System (CMS). Relapse was defined as the deterioration of symptoms meeting the relapse criteria within one year of their baseline assessment date, as documented in their CMS case notes. For the rest of the patients (n = 132), relapse status was assessed from monthly assessment based on the deterioration of symptoms meeting the relapse criteria. The relapse criteria was the presence of all the following conditions for at least one week: (1) an increase in at least one of the following PANSS27 items (delusion, hallucinatory behavior) to a score of ≥3; (conceptual disorganization, unusual thought content) to a score of ≥4; (suspiciousness) to a score of ≥5; (2) Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Severity of Illness29 scale rated ≥3; and (3) CGI Improvement scale rated ≥5. Continuous variables were also created for individual relapse item scores (e.g., PANSS delusion).

Demographic information

We examined participants’ basic demographic information (n = 152) in both intervention groups. Participants in the MBI-p group (M = 40.16, SD = 9.43) were slightly older than those in the psychoeducation group (M = 37.35, SD = 8.42; p = 0.055). Owing to its marginal significance, age was treated as a covariate in subsequent analyses. Other demographic variables such as sex, diagnosis, marital status, years of education, and untreated psychosis (DUP) were not significantly different (Table 1). Our sample consists of patients with varying durations of illness, with only 22% classified as being in early psychosis, defined as having an illness duration of less than five years. There was no significant difference between the intervention groups in the proportion of early psychosis patients (p = 0.204). Additionally, relapse rates did not differ based on the duration of illness (Supplementary Table 1).

Participants in both groups completed almost all intervention sessions (83%) with no significant difference in the proportion of lessons attended by the two groups (Supplementary Table 2).

Relapse outcome

At the one-year follow-up, 10 (13.0%) participants in the mindfulness group and 10 (13.3%) in the psychoeducation group relapsed. Both MBI-p and psychoeducation showed similar rates of relapse at one year (Odds ratio = 1.064, 95% CI [0.410, 2.762], p = 0.889), and severity of relapse, as indicated by the total and five individual relapse item scores (i.e., PANSS Delusion, Conceptual Disorganization, Hallucination, Suspiciousness/Persecution, and Unusual Thought Content) at one-year follow-up (p-values of 0.256–0.937). PP analysis showed consistent results (p-values of 0.072–0.837) with the ITT approach (Table 2).

Psychopathological comparisons

Post-intervention, the interaction effect on the CDSS was significant, in which MBI-p showed a more severe CDSS score, whereas psychoeducation showed an improvement (p = 0.024). At the one-year follow-up, the PANSS total score (p = 0.037) was significantly different; both interventions showed a more severe score, but MBI-p showed greater deterioration (Table 3).

Functioning, cognitive functioning, and life quality comparisons

Several significant interaction effects were observed after the intervention. MBI-p showed a reduction in social activities but psychoeducation showed an increase (p = 0.005), and this effect persisted at the one-year follow-up (p = 0.005; Table 3). MBI-p also presented a more severe hostility score for expressed emotions but a lower score for psychoeducation (p = 0.031). Although this did not persist at the one-year follow-up, the overall expressed emotion was significantly decreased in psychoeducation, but not in MBI-p (p = 0.046). Resilience increased significantly in psychoeducation but decreased in MBI-p (p = 0.036); however, this effect did not persist. Patients in the psychoeducation group showed a significant reduction in perceived risk of relapse, but MBI-p score increased (p = 0.035) post-intervention (Table 4).

Mindfulness comparisons

Several interaction effects were observed after intervention. The results revealed that MBI-p enhanced observing (p = 0.047) and non-reactivity to inner experiences (p = 0.007), whereas psychoeducation led to a decline in these facets. However, a decline in description (p = 0.001) and acting with awareness (p < 0.001) was found in MBI-p, whereas psychoeducation improved these facets. The effects of observing, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity to inner experiences persisted at the one-year follow-up (Table 4).

Discussion

We found that MBI-p did not prevent relapse or improve clinical symptoms better than psychoeducation but demonstrated a similar effect on mindfulness facets as Tong et al.’s pilot study. Psychoeducation shows promising benefits in enhancing secondary outcomes such as functioning and life quality among these patients.

MBI-p on relapse prevention

We found no significant differences in relapse rates or severity between the MBI-p and psychoeducation groups. Thus, MBI-p does not offer added benefits in reducing relapse rates or severity of psychoeducation among remitted patients with psychosis at the one-year mark. Few longitudinal studies have explored the long-term effects of MBI on patients with psychosis34. For instance, only one study examined MBI’s impact on relapse and found it significantly better than TAU38. However, these findings’ generalizability is uncertain owing to the treatment-group format not being specified and the relatively short illness duration in their sample (1.49 years). This lack of comparability suggests the need for replication studies to confirm MBI-p’s effectiveness in relapse prevention in patients with psychosis.

Two possible explanations for these nonsignificant results exist. First, our study directly compared MBI-p with psychoeducation without TAU. This could potentially obscure MBI-p’s effects, hampering determining its efficacy in relapse prevention. A meta-analysis examining digital-psychological intervention on depressive symptoms has shown that control groups involving psychoeducational material produce a moderate effect immediately after the intervention55. Moreover, MBI, CBT, and psychoeducation have similar effects in reducing depressive symptoms, suggesting that these interventions exert similar degrees of impact56. Second, most of our interventions took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. This contributes to enhancing psychoeducational efficacy. Hui et al. 57 found that patients with FEP were more likely exposed to stressors such as financial difficulties and job termination during the pandemic and poorer medication compliance. This suggests that our psychoeducational intervention had a greater positive impact on the sample as it focused on enhancing patients’ understanding of pharmacological treatment and its side effects, as well as stress management and exercise. This could render the relapse prevention effects comparable between the two interventions.

Notably, our overall relapse rate (10%) is lower than the expected relapse rates for both intervention groups (15% and 35%). Several factors may explain the reduced number of relapses observed in this study. Firstly, research has shown that patients within Chinese populations tend to have higher compliance rates, with 70–80% displaying positive adherence behaviors and attitudes58,59, resulting a lower relapse risk. Secondly, our sample excludes patients with substance abuse, which may contribute to the lower relapse rate observed compared to studies in Western populations. Lastly, while our expected relapse rate was based on the first-year relapse rates of the FEP population39,40 and Wang et al.‘s (2016)38 findings, our sample includes patients with varying illness durations, many of whom are relatively more stable. In fact, early psychosis only takes up to 22% of our sample. Interestingly, relapse rates did not differ based on illness duration (see Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that MBI-p may have a similar effect in both early and late-stage psychosis.

Furthermore, relapse can be influenced by various factors, including medication discontinuation, poor adjustment before the onset of illness, and critical comments from caregivers12. Medication is considered a significant factor in relapse3. However, it can be argued that the measure of medication adherence used in our study might not be sufficient to fully account for its potential confounding effect on relapse. On the other hand, the complexity of preventing relapse suggests that relying solely on one intervention may be insufficient. For instance, despite efforts to mitigate relapse through early intervention programs for psychosis, these often yield limited success60,61. MBI-p primarily focuses on stress management through mindfulness techniques, which may not comprehensively address all aspects relevant to relapse prevention. A recent review indicated that MBCT may offer a more comprehensive approach than MBSR alone. MBCT typically incorporates psychoeducation aimed at preventing depressive relapse and provides insights tailored to conditions such as schizophrenia62. This suggests that integrated interventions such as MBCT could offer more robust strategies for preventing relapse in psychosis.

MBI-p on secondary outcomes

MBI-p had a less beneficial impact on secondary outcomes than psychoeducation, likely because of the different aspects of mindfulness that each group enhanced. MBI-p enhances observation and non-reactivity to inner experiences, whereas psychoeducation elevates descriptions and acts with awareness. This aligns with the literature reporting stable effects on non-reactivity but not on describing skills63,64,65,66. Our MBI-p program prioritized awareness over verbal expressions, whereas psychoeducation emphasized social support and communication. Despite the generally positive impacts of MBI on psychosis, we postulate that differing focuses of interventions and pandemic-related challenges influence secondary outcomes such as functioning and life quality.

Psychopathology

Our findings revealed a significant interaction effect in PANSS at the one-year follow-up. Although the difference in relapse rates between the interventions was not statistically significant, the MBI-p group had a slightly greater relapse severity, leading to higher PANSS scores. This contrasts with Tong et al.’s pilot study, which showed significant PANSS improvement. This result was arguably driven by a significant improvement in the general psychopathology score, whereas the positive and negative symptom scores only mildly contributed to this effect. This suggests that MBI-p may have little effect on the reduction of psychotic symptoms in remitted patients.

In the post-intervention assessment, CDSS scores indicated that depressive symptoms worsened in the MBI-p group but improved in the psychoeducation group, with no long-term effects observed. MBI-p may have heightened awareness of negative emotions, as indicated by increased scores in the “observing” facet of the FFMQ following MBI-p. Initial negative experiences during mindfulness practice are common67,68,69. Despite this discomfort, MBI often lead to positive self-care practices and overall positive impacts. Mindfulness is a process of reconnecting with difficult thoughts and emotions, initially causing discomfort but ultimately resulting in greater self-awareness and well-being67,68. Conversely, psychoeducation likely provides practical coping mechanisms that enhance mental well-being during a pandemic.

Functioning, cognitive functioning, and life quality

We found significant interactive effects on functional and life quality outcomes, particularly social activities, hostility in expressed emotions, resilience, and perceived risk of relapse. MBI-p is generally less beneficial than psychoeducation.

Psychoeducation has led to short- and long-term improvements in social activities because of its focus on effective communication and healthy lifestyle habits through social support. Conversely, while MBI-p focuses on the individual practice of mindfulness, it might be more susceptible to the pandemic’s adverse impact, including reduced social connectivity and more stressful life events47. This may account for the decrease in psychosocial functioning in the MBI-p group.

Improved “observing” skills in MBI-p may heighten awareness of internal and external stimuli, impacting functioning. Post-intervention, the MBI-p group experienced an increased hostile attitude from the caregiver and perceived risk of relapse, whereas reductions were noted in the psychoeducation group. This heightened awareness is typical in mindfulness learning, but participants often adapt to these emotions through mindfulness techniques over time68. Our findings showed that the MBI-p group experienced slightly fewer negative emotions from others at the one-year follow-up. Moreover, the increased awareness of relapse risk in MBI-p participants (25.98%) aligned more closely with actual relapse rates in Hong Kong, indicating a more realistic perception of relapse70. Psychoeducation provides practical coping mechanisms, enhancing resilience and managing negative attitudes or relapse triggers better than MBI-p.

Limitation

Several limitations may have impacted the results of this study. Firstly, the sample size and follow-up duration might have been insufficient to detect relapse events effectively. However, there is a possibility that longer follow-up period could potentially dilute the intervention’s impact, given the relatively low intensity of MBI. Secondly, relapse is influenced by various factors, including stress and medication adherence. One limitation of this study is that, although medication adherence behavior was measured, we did not record patients’ actual medication dosages. Additionally, demographic comparisons between the two groups indicated that age was nearly significant. While age did not significantly contribute to relapse in this study, this finding suggests that the stratification process during randomization could be improved. Thirdly, our study included a mix of patients with both early-stage and longer-duration psychosis, some of whom underwent EASY interventions while others did not. Although our analysis showed that the MBI-p intervention appears to have a similar effect across stages, a large proportion of the sample had lived with the illness for more than five years, leading to a more stable cohort. Future studies may wish to focus on a more vulnerable and specific stage of psychosis, such as early psychosis, to better examine the intervention’s effects. Forth, limited information was also gathered regarding patients’ acceptance and commitment to mindfulness practices. For example, we did not adequately document patients’ perspectives on mindfulness before the intervention or the frequency and intensity of mindfulness practice after the intervention and during the follow-up period. Despite monthly reminders, this limited monitoring raises concerns about the extent of patients’ engagement with mindfulness outside the intervention sessions. To better understand the impact of mindfulness on relapse rates among patients with psychosis, future studies should more rigorously track the frequency and intensity of mindfulness practice, as well as to control for patients’ history of other psychological interventions outside of the study. Furthermore, the study period overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic, during which patients may have experienced additional benefits from psychoeducation. Replicating this study is recommended, and future research should include a TAU group to allow for a more robust comparison.

Conclusion

MBI in this study emphasized simplicity and acceptance to address fear and sadness, aiming to cultivate peace and calm while aiding in managing daily stress. Although effectiveness in preventing relapses remains uncertain, our findings indicate its lasting effect on certain mindfulness aspects. This protocol serves as a guide for future implementation, ensuring consistency even with personnel changes. We also developed supporting materials, including presentation slides, practice scripts, audio tapes, and participant booklets to facilitate ease of delivery and training. This analysis underscores the importance of targeted education within interventions, particularly during challenging periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic, to improve functioning and symptoms and create a more supportive environment for participants.

Importantly, our study highlights the varied effects of interventions on functioning and life quality in individuals with psychosis. Psychoeducation offers better support and practical skills and improves social engagement, resilience, and coping with relapse-related factors more effectively than MBI-p. These findings emphasize the need for tailored interventions to address holistic well-being in mental healthcare.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dr Hui, upon reasonable request.

References

Weiden, P. J. & Olfson, M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 21, 419–429 (1995).

Lieberman, J. A. Evidence for sensitization in the early stage of schizophrenia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 6, 155 (1996).

Chen, E. Y. H. et al. Maintenance treatment with quetiapine versus discontinuation after one year of treatment in patients with remitted first episode psychosis: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 341, c4024 (2010).

Gleeson, J. F. et al. A randomized controlled trial of relapse prevention therapy for first-episode psychosis patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70, 477 (2009).

Gumley, A. et al. Early intervention for relapse in schizophrenia: results of a 12-month randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy. Psychol. Med. 33, 419–431 (2003).

Bustillo, J. R., Lauriello, J., Horan, W. P. & Keith, S. J. The psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia: an update. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 163–175 (2001).

Bhattacharyya, S. et al. Stressful life events and relapse of psychosis: analysis of causal association in a 2-year prospective observational cohort of individuals with first-episode psychosis in the UK. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 414–425 (2023).

Birley, J. L. & Brown, G. W. Crises and life changes preceding the onset or relapse of acute schizophrenia: clinical aspects. Br. J. Psychiatry 116, 327–333 (1970).

Day, R. et al. Stressful life events preceding the acute onset of schizophrenia: a cross-national study from the World Health Organization. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 11, 123–205 (1987).

Hui, C. L. M. et al. Visual working memory deterioration preceding relapse in psychosis. Psychol. Med. 46, 2435–2444 (2016).

Ventura, J., Nuechterlein, K. H., Lukoff, D. & Hardesty, J. P. A prospective study of stressful life events and schizophrenic relapse. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 98, 407 (1989).

Alvarez-Jimenez, M. et al. Risk factors for relapse following treatment for first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Schizophr. Res. 139, 116–128 (2012).

Linszen, D. H. et al. Patient attributes and expressed emotion as risk factors for psychotic relapse. Schizophr. Bull. 23, 119–130 (1997).

Ng, R. M., Mui, J., Cheung, H. K. & Leung, S. P. Expressed emotion and relapse of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 11, 4 (2001).

Kabat-Zinn, J. & Hanh, T. N. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (Delta, 2009).

Brown, K. W. & Ryan, R. M. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 822 (2003).

Chiesa, A. & Serretti, A. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 187, 441–453 (2011).

Fjorback, L. O., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P. & Walach, H. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy–a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 124, 102–119 (2011).

Astin, J. A. Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation: effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control, and spiritual experiences. Psychother. Psychosom. 66, 97–106 (1997).

Carlson, L. E. et al. The effects of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients: 6-month follow-up. Support Care Cancer 9, 112–123 (2001).

Tsai, S. L. & Crockett, M. S. Effects of relaxation training, combining imagery, and meditation on the stress level of Chinese nurses working in modern hospitals in Taiwan. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 14, 51–66 (1993).

Speca, M. et al. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom. Med. 62, 613–622 (2000).

Chadwick, P. Person-based Cognitive Therapy for Distressing Psychosis (John Wiley & Sons, 2006).

Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constr. Hum. Sci. 8, 73 (2003).

Segal, Z., Williams, M. & Teasdale, J. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression (Guilford Publications, 2018).

Chadwick, P., Taylor, K. N. & Abba, N. Mindfulness groups for people with psychosis. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 33, 351–359 (2005).

Dannahy, L. et al. Group person-based cognitive therapy for distressing voices: pilot data from nine groups. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 42, 111–116 (2011).

Chadwick, P. et al. Mindfulness groups for distressing voices and paranoia: a replication and randomized feasibility trial. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 37, 403–412 (2009).

Chien, W. T. et al. An international multi-site, randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness-based psychoeducation group programme for people with schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 47, 2081–2096 (2017).

Langer, Á. I. et al. Applying mindfulness therapy in a group of psychotic individuals: a controlled study. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 40, 105–109 (2012).

Tong, A. C. et al. A low-intensity mindfulness-based intervention for mood symptoms in people with early psychosis: development and pilot evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 23, 550–560 (2016).

Hanh, T. N. Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life (Random House, 2010).

Rezek, C. Brilliant Mindfulness: How the Mindful Approach Can Help You Towards a Better Life (Pearson UK, 2013).

Tao, T. J. et al. Mindfulness meditation for Chinese patients with psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 237, 103–114 (2021).

Chien, W. T. & Thompson, D. R. Effects of a mindfulness-based psychoeducation programme for Chinese patients with schizophrenia: 2-year follow-up. Br. J. Psychiatry 205, 52–59 (2014).

Chien, W. T. et al. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based psychoeducation group programme for early-stage schizophrenia: an 18-month randomized controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 212, 140–149 (2019).

Wang, L. Q. et al. A randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness-based intervention program for people with schizophrenia: 6-month follow-up. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 12, 3097–3110 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. The effects of mindfulness-based psychological intervention on medication adherence and relapse in patients in recovery from schizophrenia. Chin. Med. Pharm. 9, 278–281 (2019).

Chen, E. Y. et al. A prospective 3-year longitudinal study of cognitive predictors of relapse in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Schizophr. Res. 77, 99–104 (2005).

Tao, T. J. et al. Working memory deterioration as an early warning sign for relapse in remitted psychosis: a one-year naturalistic follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 319, 114976 (2023).

Hui, C. L. M. et al. In Psychosis: Global Perspectives (eds Morgan, C., Cohen, A. & Roberts, T.) (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

Guy, W. C. Clinical global impression. In Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. 217–222 (1976).

Addington, D. et al. Reliability and validity of a depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr. Res. 6, 201–208 (1992).

Thompson, K. et al. Reliability and validity of a new medication adherence rating scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr. Res. 42, 241–247 (2000).

Brugha, T. et al. The list of threatening experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term contextual threat. Psychol. Med. 15, 189–194 (1985).

Goldman, H. H., Skodol, A. E. & Lave, T. R. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am. J. Psychiatry 149, 9 (1992).

Goodman, S. H. et al. Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the role functioning scale. Community Ment. Health J. 29, 119–131 (1993).

Birchwood, M., Smith, J. O., Cochrane, R., Wetton, S. & Copestake, S. O. The social functioning scale: the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 157, 853–859 (1990).

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M. A. & Keller, S. D. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual (Health Institute, New England Med. Center, 1995).

Ng, S. M. & Sun, Y. S. Validation of the concise Chinese level of expressed emotion scale. Soc. Work Ment. Health 9, 473–484 (2011).

Campbell‐Sills, L. & Stein, M. B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC): validation of a 10‐item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress 20, 1019–1028 (2007).

Chen, E. Y., Tam, D. K., Wong, J. W., Law, C. W. & Chiu, C. P. Self-administered instrument to measure the patient’s experience of recovery after first-episode psychosis: development and validation of the Psychosis Recovery Inventory. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 39, 493–499 (2005).

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T. & Allen, K. B. Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment 11, 191–206 (2004).

Tong, A. C., Ho, F. S., Chu, O. H. & Mak, W. W. Time-dependent changes in depressive symptoms among control participants in digital-based psychological intervention studies: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e39029 (2023).

Mak, W. W. et al. Efficacy of internet‐based rumination‐focused cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness‐based intervention with guided support in reducing risks of depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 16, 696–722 (2024).

Hui, C. L. M. et al. COVID-19 exposure and psychosis: a comparison of clinical, functional, and cognitive profiles in remitted patients with psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 328, 115487 (2023).

Hui, C. L. et al. Prevalence and predictors of medication non-adherence among Chinese patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 228, 680–687 (2015).

Hui, C. L. et al. Risk factors for antipsychotic medication non-adherence behaviors and attitudes in adult-onset psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 174, 144–149 (2016).

Chan, S. K. W. et al. 10-year outcome study of an early intervention program for psychosis compared with standard care service. Psychol. Med. 45, 1181–1193 (2015).

Chen, E. Y. H. et al. Three‐year outcome of phase‐specific early intervention for first‐episode psychosis: a cohort study in Hong Kong. Early Interv. Psychiatry 5, 315–323 (2011).

Sabé, M. et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Schizophr. Res. 264, 191–203 (2024).

Chen, Y. H., Chiu, F. C., Lin, Y. N. & Chang, Y. L. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based-stress-reduction for military cadets on perceived stress. Psychol. Rep. 125, 1915–1936 (2022).

Frank, J. L., Reibel, D., Broderick, P., Cantrell, T. & Metz, S. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on educator stress and well-being: results from a pilot study. Mindfulness 6, 208–216 (2015).

Ninomiya, A. et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy in patients with anxiety disorders in secondary‐care settings: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 74, 132–139 (2020).

Pan, W. L., Chang, C. W., Chen, S. M. & Gau, M. L. Assessing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based programs on mental health during pregnancy and early motherhood—a randomized control trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 1–8 (2019).

Lindahl, J. R., Cooper, D. J., Fisher, N. E., Kirmayer, L. J. & Britton, W. B. Progress or pathology? Differential diagnosis and intervention criteria for meditation-related challenges: perspectives from Buddhist meditation teachers and practitioners. Front. Psychol. 11, 560411 (2020).

Brooker, J. et al. Evaluation of an occupational mindfulness program for staff employed in the disability sector in Australia. Mindfulness 4, 122–136 (2013).

Cebolla, A., Demarzo, M., Martins, P., Soler, J. & Garcia-Campayo, J. Unwanted effects: is there a negative side of meditation? A multicentre survey. PLoS One 12, e0183137 (2017).

Hui, C. L. M. et al. A 3-year retrospective cohort study of predictors of relapse in first-episode psychosis in Hong Kong. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 47, 746–753 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the General Research Fund (Project number 17110918).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr Hui had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Hui, Lin, Tong, Chen. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Hui, Wong, Lui, Chiu, Evie WT Chan, Tao. Drafting of the manuscript: Hui, Wong, Chiu. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Hui, Wong, Chiu, Suen. Obtained funding: Hui.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Prof Chen has participated in the paid advisory board for Otsuka and received educational grant support from Janssen-Cilag. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hui, C.L.M., Wong, C.C.L., Lui, E.C.Y. et al. Effects of mindfulness-based intervention in preventing relapse in patients with remitted psychosis: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr 10, 120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00539-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00539-0