Abstract

Uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant persons is lower than the general population. This scoping review explored pregnant people’s attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine, reasons for vaccine hesitancy, and whether attitudes about COVID-19 vaccines differ by country of origin. A scoping review was conducted across PubMed, Embase, CINHAL, and Scopus. Inclusion criteria were articles published in English from 2019–2022 focused on attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant persons. Data analysis was done via the 5Cs framework for vaccine hesitancy: Constraints, Complacency, Calculation, Confidence, and Collective Responsibility. 44 articles were extracted. A lack of confidence in vaccine safety was the most prevalent theme of hesitancy among pregnant persons. This was largely driven by a lack of access to information about the vaccine as well as mistrust of the vaccine and medical professionals. Meanwhile, vaccine acceptance was mostly driven by a desire to protect themselves and their loved ones. Overall, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among pregnant persons continues to be high. Vaccine hesitancy is primarily driven by fear of the unknown side effects of the vaccine on pregnant persons and their fetuses along with a lack of information and medical mistrust. Some differences can be seen between high income and low- and middle-income countries regarding vaccine hesitancy, showing that a single solution cannot be applied to all who are vaccine hesitant. General strategies, however, can be utilized to reduce vaccine hesitancy, including advocating for inclusion of pregnant persons in clinical trials and incorporating consistent COVID-19 vaccine counseling during prenatal appointments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a significant change in the landscape of healthcare on a global level. As of April 2023, there have been a total of 764,474,387 cases of COVID-19 globally, with a total of 6,915,286 deaths1. When stratified by WHO defined regions, Europe had the highest number of confirmed cases (275,789,453), whereas Africa had the fewest cases (9,522,906)1. Based on COVID-19 deaths, the Americas had the highest number of COVID-19 deaths (2,945,996) and Africa had the fewest (175,343)1. In response to the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus, the development and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine was also expedited on a global level. Thus, it has become even more important for researchers and practitoners to better understand vaccine hesitancy in the lens of a pandemic.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines vaccine hesitancy as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination, despite availability of vaccination services”2. As of 2019, vaccine hesitancy was identified as one of the top 10 global health threats, as identified by WHO3. The concept of vaccine hesitancy has been a highly studied topic globally, with multiple studies that have examined vaccine hesitancy in both childhood and adulthood for a variety of diseases ranging from influenza to the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)4. Globally, vaccination uptake has been relatively high, with 13,325,228,015 vaccine doses administered. Of these doses, 72.3% (5,546,760,991) of recipients have received at least one vaccine dose and 67% (5,104,768,538) of recipients received a full primary series of doses, which differs depending on the vaccine platform1,5. When looking at global vaccination trends, it is important to address the inequity that exists in vaccine availability. Production and availability of vaccines is affected by the economic status of a country, resulting in decreased availability in many LMICs6. However, COVID-19 prevalence, mortality, and vaccination rates have all been difficult to determine for at risk populations, such as pregnant persons.

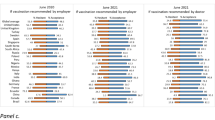

Per the CDC, it is estimated that 71.4% of pregnant persons have completed the primary COVID-19 vaccine series and 22.9% have received updated booster doses in the United States. The global rate of COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant persons, however, is estimated to only be 53.4%7. It is crucial to address vaccine hesitancy among pregnant people, as they are at a higher risk for severe consequences from COVID-19 compared to nonpregnant counterparts. Pregnant persons who get COVID-19 are at greater risk for complications, including hospitalization, admission into intensive care units (ICU), intubation, and death8. Moreover, pregnant patients who have a symptomatic COVID-19 disease course have nearly three times the odds of developing adverse maternal outcomes (e.g. ICU admission, invasive ventilation, preterm delivery, death) than pregnant patients who do not have COVID-198. There also is a discrepancy regarding the approach to COVID-19 vaccine policies among different countries. There are 121 countries that explicitly recommend COVID-19 vaccination of pregnant persons, with 64 additional countries that allow pregnant persons to receive the COVID-19 vaccination, but do not have official recommendations9. Finally, there are 9 countries that in which certain groups of pregnant persons, such as healthcare workers and pregnant persons with chronic conditions, can receive the vaccine, but no explicit recommendation is issued. One country (Cote d’Ivoire) that does not recommend COVID-19 vaccination, with exceptions, and nine countries that do not recommend COVID-19 vaccines at all for pregnant persons.

The exclusion of pregnant persons from COVID-19 vaccine trials likely have affected vaccine uptake among this group10. In general, pregnant persons have been excluded from 69% of all clinical trials in the U.S., with the COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials being no exception11. Due to this, initial recommendations were that pregnant persons should not receive the vaccine until more data were gathered. These initial recommendations were also influenced by an initial lack of evidence that pregnant persons were at high risk for severe illness secondary to a COVID-19 infection. Early in January 2021, the prevailing opinion of professional organizations such as the WHO, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine was that vaccination during pregnancy was an individual’s choice and was not uniformly recommended to all pregnant persons12. These recommendations changed as information about COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and safety as well as evidence highlighting that pregnant persons as a high-risk population were published through the course of the pandemic, with COVID-19 vaccines currently being highly recommended for pregnant persons in the US.

Vaccination rates among pregnant persons are currently estimated to be lower than those of the general population7, implying that pregnant persons are among the most hesitant to receive the vaccine13. This scoping review aims to explore pregnant people’s attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine, reasons for vaccine hesitancy, and whether attitudes about COVID-19 vaccines differ by country of origin. In addition, this review will provide guidance on how to address vaccine hesitancy in this special-risk group, which could potentially increase uptake.

Results

The final search strategy, modified for each database, resulted in a total of 1343 citations that were uploaded to Covidence. After 199 duplicate citations were removed, a reminder of 1144 citations were screened by title and abstract, resulting in 125 studies being eligible for full text review. A final count of 44 studies were extracted for analysis. The detailed search process is illustrated via the PRISMA chart in Fig. 1.

Flowchart for article retrieval process

Among the 44 included studies, 38 were quantitative, one was qualitative, and five were mixed methods. A total of 40,934 participants were included from 39 different countries: thirteen countries in Europe, six countries in the Western Pacific Region, eight countries in the Americas, five countries in Africa, four counties in the Eastern Mediterranean region, and three countries in South-East Asia (Table 1).

Reasons for vaccine hesitancy

Among extracted articles, reasons given by pregnant persons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were collected and sorted into themes based on the 5Cs framework. All five categories of this framework were represented: Confidence, Complacency, Constraints, Collective Responsibility, and Calculation (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Confidence

In the context of vaccine hesitancy, a lack of confidence is defined as a lack of trust in vaccines, vaccine delivery systems, and political figures overseeing vaccination programs. A lack of confidence in the vaccination was a major theme of vaccine hesitancy found among all 44 extracted articles14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. Among all 44 studies, concerns regarding the safety of the vaccine, both for themselves and their fetuses, were brought up by pregnant persons. Across 37 articles, pregnant participants feared adverse effects and health complications after getting vaccinated, especially for pregnant persons with chronic medical conditions14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,42,43,44,45,49,50,52,53,54,55,56,57. Specific concerns mentioned by pregnant persons included infertility15,21,23,28,29,30,31, postpartum hemorrhage16, and death31. In two studies in the United States, pregnant persons were concerned that harmful ingredients were present in the vaccines14,23. Meanwhile, among 33 studies, pregnant participants feared that the vaccine would not be safe for their fetus14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,46,47,53,54,55,56,57. Specific concerns mentioned by pregnant persons included fear of congenital malformations, hearing and visual impairments, preterm birth, and miscarriages14,16. Pregnant persons in 5 studies did indicate that they may feel comfortable getting vaccinated post-pregnant or post-breastfeeding22,29,30,40,41.

Pregnant persons expressed mistrust in the vaccine due to the lack of data about safety and efficacy, including the lack of representation of pregnant persons in clinical trials, a sentiment seen among 34 studies15,16,17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,51,53,55. Among 7 studies, pregnant persons demonstrated discomfort with the rapid development and approval of the COVID-19 vaccine23,30,35,39,40,47,48. Pregnant patients specifically in Afghanistan31, Romania43, and Ethiopia49 had concerns about the quality of the vaccine in their respective home countries. Among subjects in 8 studies, there was a fear that the vaccine would cause pregnant persons to get a COVID-19 infection15,18,19,23,25,30,40,45. Across 18 studies, mistrust of the medical and political systems that encouraged vaccination was prevalent among pregnant persons14,15,16,21,23,28,29,30,31,40,41,43,44,45,47,49,50,51. Mistrust of the medical systems can be broken down into lack of belief in the existence of the pandemic and mistrust of medical providers. Disbelief in the pandemic itself was seen among five studies from Romania50, Palestine21, the United States41, Poland28, and Ethiopia15, meanwhile mistrust of medical providers was a theme only seen in three studies conducted in the United States23,30,51. Another theme that was only reiterated among multiple studies conducted in the United States was explicit mistrust of the government, seen among 21–30% of pregnant persons23,30,40,44,51. In Romania specifically, 23% of unvaccinated pregnant persons believed that the vaccine was a conspiracy theory43. Meanwhile, in Afghanistan31 and Ethiopia16, some pregnant persons believed that the vaccine had magnetic properties, bad spirits, or mind controlling abilities.

Complacency

In the context of vaccine hesitancy, complacency can be defined as believing that the vaccine is not necessary for health or that there are limited perceived risks to the disease for which vaccination is being considered. The theme of complacency was seen across 33 articles14,15,16,17,18,19,20,22,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,40,41,42,43,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Some pregnant persons believed that all vaccines were unnecessary. This was most frequently observed in pregnant persons from the United States and Canada across five studies, with up to 13.8% of pregnant persons agreeing with this sentiment35,40,41,45,48. A general belief that the COVID-19 vaccine was not necessary was seen mostly among high and upper middle income countries including Australia (6–10%)17, the United States (1.4–22%)14,33, and Turkey (14.12%)20. Among 6 studies, pregnant persons stated they would prefer to utilize other methods besides vaccination to protect themselves from COVID-1915,16,18,20,30,40. In a United States study, 21.5% of pregnant persons preferred to use masks and other non pharmaceutical interventions over vaccines40. Other methods of protection were also suggested by pregnant persons, including the preparation of spicy foods in Ethiopia16. Meanwhile, pregnant persons from Afghanistan31, Poland32, Ukraine32, the United States30,36,40,41, England29, Romania50, Ethiopia16, and Vietnam27 believed they had already built-up natural immunity to COVID-19 and thus would not require vaccination. There was also the belief, ranging from 2.6% to 13.5% of pregnant participants, that COVID-19 was not a serious disease19,20,25,40,42,50,51. In addition to this belief, pregnant persons from a multitude of countries believed that they were not classified as a high-risk group and therefore did not need the vaccination15,19,22,25,28,34,38,40,42,45,48,51,53,54.

Constraints

In the context of vaccine hesitancy, constraints can be defined as structural barriers–including but not limited to low health literacy, affordability, accessibility, and availability–that prevent vaccination. The theme of Constraints was seen across 14 studies15,19,21,23,25,30,32,35,38,40,49,51,53,54. Limited availability of vaccines were barriers for 1.3% of pregnant persons in Poland32, 6.7% of pregnant persons in Ukraine32, 9.7% of pregnant persons in the United States40 and 40.6% of pregnant persons in Palestine21. Among two United States studies, 4.1–9.7% of pregnant persons noted they did not know where to get vaccinated23,40. In Japan53 and Jordan54, 16.5–23.5% of pregnant participants stated they did not have enough time to get vaccinated. In China, 3.8% of pregnant persons believed that the vaccination process was unnecessarily complicated38. In seven studies, a fear of needles was seen as a barrier to vaccination for 4.2–37.1% of pregnant persons15,19,21,25,35,40,51. Costs associated with vaccination were seen as a barrier to vaccination among 2.2–9.6% of pregnant participants in Jordan (2.2%)54, Ethiopia (5.06%)49, China (7%)38, and the United States (9.6%)40. In one US based study, there were concerns about the racial inequity in vaccine access, especially among pregnant persons of racial and ethnic minorities30.

Collective responsibility

In the context of vaccine hesitancy, collective responsibility can be defined as the desire or willingness to protect others. The theme of collective responsibility was seen across 12 studies15,16,19,21,25,30,43,45,49,50,52,54. Hesitancy from family members and partners influenced hesitancy among 2.8–47% of pregnant participants15,19,21,25,30,45. Meanwhile, hesitancy from friends only influenced hesitancy among a small proportion of pregnant participants in Jordan54 and Italy25, with less than 10 participants in each study reporting being influenced by friends. Rumors about the COVID-19 that spread through social media also influenced pregnant persons’ hesitancy in two studies, one in the United States45 and one in Romania50. Religion also played a role in influencing the decision to get vaccinated among pregnant people in South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh)52, Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, DRC, Zambia)15,16,49,52, Latin America (Guatemala)52, and Eastern Europe (Romania)43.

Calculation

In the context of vaccine hesitancy, calculation can be defined as individuals seeking information prior to making a decision about getting a vaccine. The theme of Calculation was present among 11 studies15,23,25,29,30,40,45,46,50,51,55. Pregnant participants within these studies noted they did not have sufficient knowledge about the vaccine or COVID-19 to make the decision to get vaccinated30,40,45,46,50,51. A lack of recommendation or an explicit recommendation against the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy from medical providers influenced 2.1–22.2% of pregnant patients to not get the vaccine15,25,29,40,45,55. This phenomenon was mostly seen in England29,55, the United States40,45, Italy25 and Ethiopia15 but was more predominant among the three high income countries.

Reasons for vaccine acceptance

Among extracted articles, reasons given by pregnant persons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were collected and sorted into themes based on the 5Cs framework. Four out of the five categories of this framework were represented: Collective Responsibility, Confidence, Complacency, and Calculation (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Collective responsibility

The theme of Collective Responsility was one of the most common themes for vaccine acceptance and was seen across 22 articles14,16,17,20,21,22,24,28,30,35,39,41,43,46,47,48,49,53,54,55,56,57. Pregnant persons chose to get the vaccine to protect their fetus, their family, and their community, a theme that was seen across all countries. Protecting their fetuses was most common, and noted across 16 studies17,20,21,22,24,30,33,36,39,41,46,49,54,55,56,57. Pregnant persons chose to get vaccinated to protect their fetus from COVID-19 and its consequences, including ICU admissions or death39. Pregnant persons also wanted to protect their future pregnancies30 and hoped that they would be able to pass immunity to their fetus during pregnancy and breastfeeding21,30,41,57. Across 13 studies, pregnant persons chose to get vaccinated because they wanted to protect their family members, especially those who were high-risk and had other comorbidities17,22,24,30,33,35,39,41,46,49,53,54,55. There was also a sense of moral responsibility to protect their community, which was seen across 12 studies14,17,20,24,30,33,35,43,47,48,49,53. Along with this sense of moral responsibility was the desire to return to normal life21,30,35,43,49, be able to travel30,43, stop wearing a mask30, and see family and friends without restrictions30. This was seen at a high rate among pregnant persons in Romania (38.5–90.2%)43, Canada (57.3%)35, and Palestine (36.6%)21, while only seen 11% of pregnant persons from Ethiopia49.

Confidence

The theme of confidence was the other most common theme for vaccine acceptance and was seen across 22 articles14,16,17,20,21,22,24,30,33,35,39,41,43,45,48,49,50,53,54,55,56,57. Pregnant persons demonstrated a general trust in vaccine safety and effectiveness, as seen across eight studies14,17,21,24,30,39,49,50. Five of these studies were conducted in high income countries (Australia17, the United States14,30, Romania50, and Ireland24) while only three were conducted in lower- and middle-income countries (Palestine21, Turkey39, and Ethiopia49). Pregnant persons in the United States and Ireland noted that they had increased motivation to accept the vaccine due to the information and data available regarding the safety of COVID-1914,24,30. A few of these individuals said that participating in clinical trials or seeing data from pregnant women in clinical trials also increased their likelihood to get the vaccine14,24,30. More specifically, pregnant persons believed that the vaccine would protect them from COVID-19 and its complications14,16,17,20,21,22,24,30,33,35,39,41,43,48,49,53,54,55,56,57. Among six studies, many pregnant participants classified themselves as high risk due to chronic illnesses or due to their pregnancy; thus, they wanted to further protect themselves by getting vaccinated16,20,30,49,53,57. Another fear among pregnant participants specifically in Ethiopia was the fear of death from COVID-19, which promoted many to get vaccinated16,49.

Calculation

The theme of calculation was seen across 8 studies28,30,35,39,43,49,53,57. The most common source of information and recommendations reported by pregnant persons was healthcare professionals, a trend seen across six studies28,30,35,43,49,57. Meanwhile, the influence of family, friends, and social media on vaccine acceptance was only reported by pregnant persons from Japan53 and Turkey39.

Complacency

The theme of complacency was seen across six articles30,41,46,49,53,54. Between 10.2% and 88% of pregnant participants in Germany46, Japan53, Jordan54, and the United States30 were required to get the vaccine for their jobs, especially if they were healthcare workers. Whereas 6.5% of pregnant participants from an Ethiopian study noted that government recommendations of vaccinations influenced their decision to get vaccinated49. Additionally, among two United Sates studies, there was a small number of participants who chose to get vaccinated to avoid re-infection from COVID-1930,41 or because they knew someone who had died due to COVID-19 related complications30.

Discussion

Vaccine hesitancy among pregnant persons is complex and multifactorial. A lack of confidence in vaccine safety was the most prevalent theme of hesitancy among pregnant persons. This was largely driven by a lack of access to information about the vaccine as well as mistrust of the vaccine and medical professionals. Meanwhile, vaccine acceptance was mostly driven by pregnant persons’ desires to protect themselves and their loved ones, along with trust in the vaccine and the information provided about the safety of the vaccine.

Both vaccine hesitancy and acceptance were strongly driven by motivations to protect pregnant persons’ families and fetuses. Those who accepted the vaccine believed in the safety of the vaccine and believed that getting vaccinated would protect those around them. Meanwhile, pregnant persons with vaccine hesitancy believed that the vaccine was too experimental, and they were protecting their fetus from potential side effects of the vaccine. Similar trends were seen in a recent study conducted in Japan that found vaccine hesitancy among 51.5% of pregnant women58. This, coupled with the fact that most pregnant persons in these studies were open to other vaccinations, shows that COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy is not driven by anti-vaccination sentiments. Rather, it comes from fear of the unknown. In a 2017 systematic review conducted on influenza hesitancy, it was found that hesitancy comes from a lack of knowledge and fear of adverse effects rather than a belief that vaccinations do not work59. It is possible that throughout the pandemic, pregnant persons had an increase in confidence in the vaccine as more knowledge was made public regarding the vaccine and its safety profile.

A limited number of studies in this review, concentrated in the United States and Ireland, were the only ones to consider inclusion of pregnant persons in clinical trials as a reason for vaccine acceptance. This suggests that visibility of, and information regarding clinical trials may be more accessible in countries with more resources. However, there is not enough information to support this justification as globally there is a general lack of inclusion of pregnant persons in clinical trials. The lack of pregnant persons in COVID-19 related clinical trials at the start of the pandemic laid the foundation for mixed messaging to pregnant persons. In a systematic review published in the Lancet, 75% of clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments excluded pregnant women60. The shift from not recommending the vaccine to explicitly encouraging all doses of the vaccines while pregnant may have increased mistrust and confusion among pregnant persons. However, there are many ethical considerations that must be factored into discussions surrounding inclusion of pregnant persons in clinical trials. A recent publication with a study population of 24 pregnant persons found that 58.3% of them would be unwilling to participate in a hypothetical COVID-19 clinical trial while pregnant61. Some of the reasons cited for refusal included concerns that the drug is not safe, fear about the consequences of the drug on themselves or their fetuses, and not enough trust in the current scientific data published61. Based on the study, factors that increased willingness to participate in the study include willingness to contribute to science and help other pregnant persons, receiving adequate information from providers regarding necessity and safety of the clinical trial, and support from loved ones61.

Efforts have been made to advocate for the inclusion of pregnant persons in clinical trials. As per the 21st Century Cures Act, which became law in December 2016 in the United States, the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women was created62. Some recommendations from this taskforce included working to increase representation of pregnant persons in clinical trials, working with the FDA to remove pregnant persons from the vulnerable persons categorization, removing regulatory barriers that prevent pregnant persons from being in clinical trials and increasing public awareness surrounding this issue63. After the creation of this task force, substantial progress in these efforts have been made. This can be seen via the work of the Pregnancy Research Ethics for Vaccines, Epidemics, and New Technologies (PREVENT) group based out of the Johns Hopkins German Institute of Bioethics64. During its first year, the group focused on creating guidelines for inclusion of pregnant persons during the development of the Zika Virus64. The most recent example of improvements in this area can be seen by the FDA approval of the RSV vaccine for pregnant persons65. This vaccine was approved after two different clinical trials that had a sample population of only pregnant persons65.

Vaccine hesitance and acceptance is also contingent upon recommendations from and trust in medical providers. While a lack of recommendation from providers pushed vaccine hesitant pregnant persons away from vaccination, positive recommendations from providers lead to increased rates of vaccine acceptance. The fear of infertility was a common concern across pregnant persons and was a result of the lack of information given as well as the rise in mistrust in scientific information and medical providers. While studies have shown that the COVID-19 vaccine has no impact on fertility66, this has not been disseminated properly to the general public. A 2022 systematic review discussed the lack of evidence to prove that the COVID-19 vaccine causes infertility and recommended increased patient education regarding this misinformation66. In several of the extracted articles, investigators noted the importance of improved dissemination of information about the benefits and safety of COVID-19 vaccines. Even if information dissemination improves, medical mistrust will also need to be addressed. When evaluating mistrust, mistrust of providers was a theme that was only seen in the United States, while the theme of mistrust in the quality of the vaccine itself was seen among some of the LMICs (e.g., Afghanistan and Ethiopia) represented in our study. The increased prevalence of mistrust of providers among pregnant persons in the United States is likely due to both barriers, including lack of information about the vaccine and lack of access to healthcare, and racial disparities that affect COVID-19 diagnosis, hospitalization, and mortality rates4. While this suggests that the causes of mistrust are different among HICs and LMICs, it is important to note that not all studies differentiated between different mechanisms of mistrust. These findings are consistent with the conclusions drawn from literature review conducted in 2021, which also demonstrated that hesitancy and acceptance vary based on geographical location and cultural context2.

Approaches to addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy should target improving health literacy among pregnant persons and improving access to timely information about vaccines. Such information should focus on the safety and efficacy of the vaccine for both pregnant persons and their fetuses to assuage common concerns pregnant individuals often have. While the creation of large-scale public health campaigns can improve dissemination of information on a wide scale, it is equally important for resources to be directed towards improving the provider-patient relationship. Improving open-communication skills and focusing on joint-decision making with patients can improve the quality of the provider-patient relationships. There are many common models that are used for patient-centered language, two being the AIDET (Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, Thank you) and RESPECT (Rapport, Empathy, Support, Partnership, Explanation, Cultural Competency, Trust) frameworks67. The ACOG discusses these two models and encourages the utilization of patient centered language in clinical encounters67. This, in conjunction with consistent COVID-19 vaccine counseling during prenatal care, can increase the likelihood of pregnant patients trusting recommendations made by providers. Above all, the most important recommendation to improve vaccine uptake is to include pregnant persons in clinical trials and allow for autonomous decision making surrounding their participation. Improving representation of pregnant persons in clinical trials will allow for more accurate information on the safety of vaccines and drugs, thus allowing for better communication of health-related information to patients. While broad scaled recommendations can be made to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake among pregnant persons, it is important to keep in mind that such recommendations will not fit all individuals, especially on a global scale. As the review shows, there were some differences between high income countries and low- and middle-income countries. Therefore, when adapting these recommendations, it is important to consider geographical and cultural contexts and to understand the underlying reasons driving hesitancy among the target population.

Our scoping review had many strengths. This review was performed with a robust and transparent methodology. A broad literature search was conducted via multiple databases with a thorough and comprehensive search stratergy, that had been revised multiple times prior to the final extraction of articles. Our scoping review was conducted via Covidence, which allowed for the use of standardized evaluation tools utilized by our reviewers. Through this review, we were able to evaluate and present a summary of the current literature depicting global vaccine hesitancy trends among pregnant persons.

Due to the nature of a scoping review, it is possible that we were not able to identify and analyze all articles published on the topic of vaccine hesitancy among pregnant persons. As our time frame was only from 2019 to 2022, any studies published after that time frame were not included. We also do not have an equal number of studies from HIC and LIMC studies, and a large majority of our cases come from the USA. Thus, these findings cannot be broadly generalized.

Overall, levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among pregnant persons is high. Vaccine hesitancy is primarily driven by fear of unknown side effects of the vaccine upon pregnant persons and their fetuses, along with a lack of information and medical mistrust. Some differences can be seen between HIC and LMIC regarding the motivations that guide vaccine hesitancy, showing that a single solution cannot be applied to all who are vaccine hesitant. General strategies that can be utilized to improve vaccine uptake, including advocating for the inclusion of pregnant persons in clinical trials and incorporating consistent COVID-19 vaccine counseling based on information from the appropriate governing bodies and professional societies during prenatal appointments are feasible solutions to this growing problem.

Methods

A scoping review methodology was chosen to interrogate existing literature on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy or attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant persons and to uncover the remaining gaps to inform future research efforts. Findings of this scoping review are reported based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) guidelines. A literature search was conducted across PubMed, Embase, CINHAL, and SCOPUS on October 2nd, 2022. Inclusion criteria included articles published in English between 2019 and 2022 focused on reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy or attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant people. Articles were included if they focused on either the primary vaccine series or subsequent booster vaccines. Articles not focused on pregnant persons and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were excluded, along with commentaries, review articles, meta-analyses, and non-peer reviewed studies. The search strategy focused on four main concepts: Pregnancy, COVID-19, Vaccine, and Hesitancy. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used along with database specific subject headings (e.g. MeSh terms in PubMed).

Three independent reviewers performed initial citation screenings with interrater reliabilities of 0.95 (k = 0.78), 0.91 (k = 0.64), 0.97 (k = 0.87). Two independent reviewers reviewed citations during the full-text extraction stage with an interrater reliability of 0.8 (k = 0.57). The following data were extracted from each study: study information (location, methodology, sample size, study timeline); demographic information (age, race/ethnicity, gravidity, and parity status); quantification of vaccine hesitant and non-hesitant participants; vaccination status; definition of vaccine hesitance and vaccine acceptance; reasons for vaccine hesitance and vaccine acceptance; correlates and predictors of vaccine hesitance and acceptance; recommendations to improve COVID-19 vaccine uptake among pregnant persons; acceptance and hesitance of other vaccines.

Quality appraisal, conducted via Covidence, looked at appropriateness of the study methodology, objectiveness of data, conflict of interest, sample size, analysis methodology, statistically significant results, and identification of potential confounders. Results of the quality appraisal can be found in Fig. 3.

Data analysis was guided by the 5 C model, a behavioral model proposed by Corenlia Betsch and her team which has been commonly used to assess vaccine acceptance and hesitancy68. The 5 Cs in this model are Confidence, Complacency, Constraints, Calculation and Collective Responsibility, which are defined below68. Through this model, the psychological underpinnings of vaccine hesitancy and acceptance can be better understood. This model was chosen for data analysis as it is a commonly recognized methodology that has been used to assess vaccine acceptance and hesitancy with other vaccines as well. This model was used to categorize and report the responses from pregnant participants across included articles.

Confidence: Trust in vaccine safety and efficacy; Trust in vaccine delivery systems; Trust in policy makers.

Complacency: Perceived risks of vaccine preventable diseases; Vaccination not deemed necessary or important.

Constraints: Accessibility, availability, and affordability of vaccines; Health literacy; Other structural barriers that prevent vaccine uptake.

Calculation: Individuals seeking information about vaccination prior to decision making.

Collective responsibility: The willingness to protect others and influence from others.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors.

References

WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://covid19.who.int.

Sallam, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 9, 160 (2021).

de Albuquerque Veloso Machado, M., Roberts, B., Wong, B. L. H., van Kessel, R. & Mossialos, E. The relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine hesitancy: a scoping review of literature until august 2021. Front. Public Health 9, 747787, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.747787 (2021).

Zhang, V., Zhu, P. & Wagner, A. L. Spillover of vaccine hesitancy into adult COVID-19 and influenza: the role of race, religion, and political affiliation in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 3376 (2023).

Holder, J. Tracking coronavirus vaccinations around the world. The New York Times (29 January 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html.

Ning, C. et al. The COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine inequity worldwide: An empirical study based on global data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 5267 (2022).

Azami, M., Nasirkandy, M. P., Ghaleh, H. E. G. & Ranjbar, R. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 17, e0272273 (2022).

Badell, M. L., Dude, C. M., Rasmussen, S. A. & Jamieson, D. J. Covid-19 vaccination in pregnancy. BMJ 378, e069741 (2022).

COMIT. Public Health Authority Pregnancy Policy Explorer. https://www.comitglobal.org/explore/public-health-authorities/pregnancy (2023).

Klein, S. L., Creisher, P. S., & Burd, I. COVID-19 vaccine testing in pregnant females is necessary. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e147553 (2021).

Thiele, L., Thompson, J., Pruszynski, J. & Spong, C. Y. Gaps in evidence-based medicine: underrepresented populations still excluded from research trials following 2018 recommendations from the Health and Human Services Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 227, 908–909 (2022).

Rubin, R. Pregnant people’s Paradox—Excluded from vaccine trials despite having a higher risk of COVID-19 complications. JAMA 325, 1027–1028 (2021).

Firouzbakht, M., Sharif Nia, H., Kazeminavaei, F. & Rashidian, P. Hesitancy about COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study based on the health belief model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 611 (2022).

Levy, A. T., Singh, S., Riley, L. E. & Prabhu, M. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy: a survey study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 3, 100399 (2021).

Tefera, Z. & Assefaw, M. A mixed-methods study of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its determinants among pregnant women in Northeast Ethiopia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 16, 2287–2299 (2022).

Aynalem, B. Y., Melesse, M. F. & Zeleke, L. B. COVID-19 vaccine acceptability and determinants among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care services at Debre Markos town public health institutions, Debre Markos Northwest Ethiopia: mixed study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 41, 293 (2022).

Rikard-Bell, M. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and the reasons for hesitancy. A multi-centre cross-sectional survey. J. Paediatr. Child Health 58, 28–29 (2022).

Mose, A. & Yeshaneh, A. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in southwest Ethiopia: Institutional-based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 2385–2395 (2021).

Goncu Ayhan, S. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in pregnant women. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Organ. Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 154, 291–296 (2021).

Ercan, A., Şenol, E. & Firat, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 32, 7–12 (2022).

Qasrawi, H. et al. Perceived barriers to Palestinian pregnant women’s acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination using the Health Believe Model: a cross-sectional study. Women Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2022.2108194 (2022).

Egloff, C. et al. Pregnant women’s perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine: A French survey. PloS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263512 (2022).

Sutanto, M. Y. et al. Sociodemographic predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and leading concerns with COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women at a South Texas clinic. J. Matern-Fetal Neonatal. Med. 35, 10368–10374 (2022).

Geoghegan, S. et al. “This choice does not just affect me.” Attitudes of pregnant women toward COVID-19 vaccines: a mixed-methods study; BioNTech; Pfizer. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 17, 3371–3376 (2021).

Colciago, E., Capitoli, G., Vergani, P., & Ornaghi, S. Women’s attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy: a survey study in Northern Italy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 62, 139–146 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14506 (2022).

Pairat, K. & Phaloprakarn, C. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy among Thai pregnant women and their spouses: a prospective survey. Reprod. Health 19, 74–0 (2022).

Nguyen, L. H. et al. Acceptance and willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women in Vietnam. Trop. Med. Int. Health TM IH 26, 1303–1313 (2021).

Nowacka, U. et al. COVID-19 vaccination status among pregnant and postpartum women-a cross-sectional study on more than 1000 individuals. Vaccines. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081179 (2022).

Husain, F. et al. COVID-19 vaccination uptake in 441 socially and ethnically diverse pregnant women. PloS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271834 (2022).

Sutton, D. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant, breastfeeding, and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 3, 100403 (2021).

Nemat, A. et al. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine refusal among Afghan pregnant women: a cross sectional study. Sci. Rep. 12, 14057–1405 (2022).

Januszek, S. et al. Approach of pregnant women from Poland and the Ukraine to COVID-19 vaccination-the role of medical consultation. Vaccines. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10020255 (2022).

Battarbee, A. N. et al. Attitudes toward COVID-19 illness and COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women: A cross-sectional multicenter study during august-december 2020. Am. J. Perinatol. 39, 75–83 (2022).

Ward, C., Megaw, L., White, S., & Bradfield Z. COVID-19 vaccination rates in an antenatal population: A survey of women’s perceptions, factors influencing vaccine uptake and potential contributors to vaccine hesitancy. Aust. N Z J. Obstet. Gynaecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13532 (2022).

Reifferscheid, L. et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and intention during pregnancy in Canada. Can. J. Public Health Rev. Can. Sante Publique 113, 547–558 (2022).

Mattocks, K. M. et al. Examining pregnant veterans’ acceptance and beliefs regarding the COVID-19 vaccine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 37, 671–678 (2022).

Tatarević, T., Tkalčec, I., Stranić, D., Tešović G., & Matijević R. Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant women on maternal immunization against COVID-19 in Croatia. J. Perinat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2022-0171 (2022).

Tao, L. et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum. Vacc. Immunother. 17, 2378–2388 (2021).

Uludağ, E., Serçekuş, P., Yıldırım, D. F. & Özkan, S. A qualitative study of pregnant women’s opinions on COVID-19 vaccines in Turkey. Midwifery 114, 103459 (2022).

Razzaghi, H. et al. COVID-19 vaccination and intent among pregnant women, United States, april 2021. Public Health Rep. Wash. DC 1974 137, 988–999 (2022).

Huang, L., Riggan, K. A., Ashby, G. B., Rivera-Chiauzzi, E. & Allyse, M. A. Pregnant and Postpartum patients’ views of COVID-19 vaccination. J. Commun. Health 47, 871–878 (2022).

Ghamri, R. A. et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer Adherence 16, 861–873 (2022).

Citu, C. et al. Appraisal of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance in the Romanian pregnant population. Vaccines. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10060952 (2022).

DesJardin, M., Raff, E., Baranco, N. & Mastrogiannis, D. Cross-sectional survey of high-risk pregnant women’s opinions on COVID-19 vaccination. Women’s Health Rep. N. Rochelle N. 3, 608–616 (2022).

Redmond, M. L. et al. Learning from maternal voices on COVID-19 vaccine uptake: Perspectives from pregnant women living in the Midwest on the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine. J. Commun. Psychol. 50, 2630–2643 (2022).

Schaal, N. K., Zöllkau, J., Hepp, P., Fehm, T. & Hagenbeck, C. Pregnant and breastfeeding women’s attitudes and fears regarding the COVID-19 vaccination. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 306, 365–372 (2022).

Skjefte, M. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36, 197–211 (2021).

Perrotta, K. et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among pregnant people contacting a teratogen information service. J. Genet. Couns. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1608 (2022).

Kebede, F., Kebede, B. & Kebede, T. Covid-19 vaccine acceptance and predictors of hesitance among antenatal care booked pregnant in North West Ethiopia 2021: Implications for intervention and cues to action. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 11, 49–59 (2022).

Citu, I. M. et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among Romanian pregnant women. Vaccines. 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10020275 (2022).

Simmons, L. A., Whipps, M. D. M., Phipps, J. E., Satish, N. S. & Swamy, G. K. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine uptake during pregnancy: “Hesitance”, knowledge, and evidence-based decision-making. Vaccine 40, 2755–2760 (2022).

Naqvi, S. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pregnant women regarding COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy in 7 low- and middle-income countries: An observational trial from the Global Network for Women and Children’s Health Research. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17226 (2022).

Hosokawa, Y. et al. The prevalence of COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine hesitancy in pregnant women: An internet-based cross-sectional study in Japan. J. Epidemiol. 32, 188–194 (2022).

Abuhammad, S. Attitude of pregnant and lactating women toward COVID-19 vaccination in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. J. Perinat. Med. 50, 896–903 (2022).

Davies, D., McDougall, A., Prophete, A., Sivashanmugarajan, V. & Yoong, W. Covid-19 vaccination: uptake and patient perspectives in a multi-ethnic North-London maternity unit. BJOG Int J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 129, 150–151 (2022).

Ekmez, M. & Ekmez, F. Assessment of factors affecting attitudes and knowledge of pregnant women about COVID-19 vaccination. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. J. Inst. Obstet. Gynaecol. 42, 1984–1990 (2022).

Lis‐Kuberka, J., Berghausen‐Mazur, M., & Orczyk‐Pawiłowicz, M. Attitude and level of COVID‐19 vaccination among women in reproductive age during the fourth pandemic wave: a cross‐sectional study in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116872 (2022).

Takahashi, Y. et al. COVID-19 vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women and mothers of young children in Japan. Vaccine 40, 6849–6856 (2022).

Schmid, P., Rauber, D., Betsch, C., Lidolt, G. & Denker, M. L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior – A systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 – 2016. PLOS ONE 12, e0170550 (2017).

Taylor, M. M. et al. Inclusion of pregnant women in COVID-19 treatment trials: a review and global call to action. Lancet Glob. Health 9, e366–e371 (2021).

Marbán-Castro, E. et al. Acceptability of clinical trials on COVID-19 during pregnancy among pregnant women and healthcare providers: a qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 10717 (2021).

Rubin, R. Addressing barriers to inclusion of pregnant women in clinical trials. JAMA 320, 742–744 (2018).

NICHD. List of Recommendations from the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women (PRGLAC). (2019). https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/advisory/PRGLAC/recommendations.

Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. PREVENT (Pregnancy Research Ethics for Vaccines, Epidemics, and New Technologies). (n.d.). https://bioethics.jhu.edu/research-and-outreach/projects/prevent/.

CDC. Healthcare Providers: RSV Vaccination for Pregnant People. (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/rsv/hcp/pregnant-people.html.

Zaçe, D., La Gatta, E., Petrella, L. & Di Pietro, M. L. The impact of COVID-19 vaccines on fertility-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 40, 6023–6034 (2022).

ACOG. Effective Patient–Physician Communication. https://www.acog.org/en/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/02/effective-patient-physician-communication (2014).

Betsch, C. et al. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLOS ONE 13, e0208601 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health grant, U54AG062333, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award [Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation grant to Johns Hopkins University, U01FD005942, awarded to SLK] funded by the Office of Women’s Health/FDA/HHS

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IC, AK, HT, LSC, HG, SLB, CP, LB, AP, HHM, ALC, IB, SLK, RM: made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data, assisted in drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the completed version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casubhoy, I., Kretz, A., Tan, HL. et al. A scoping review of global COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among pregnant persons. npj Vaccines 9, 131 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00913-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00913-0

This article is cited by

-

Cultural-Social-Economic Background and Community Engagement Impacting COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake Among Pregnant and Lactating Refugee Women

Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health (2026)

-

Vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women in the U.S. and its implication for maternal and child health

Discover Public Health (2025)

-

Understanding the rise of vaccine refusal: perceptions, fears, and influences

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Pregnancy reduces COVID-19 vaccine immunity against novel variants

npj Vaccines (2025)

-

Comparison of Adverse Events in Pregnant Persons Receiving COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccines: A Disproportionality Analysis Using Combined Data from US VAERS and EudraVigilance Spontaneous Report Databases

Drug Safety (2025)