Abstract

The recently deployed RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine induces a strong antibody response to the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) on the surface of the Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite which is associated with protection. The anti-CSP antibody titre falls rapidly after primary vaccination, associated with a decline in efficacy, but the antibody titre and the protective response can be partially restored by a booster dose of vaccine, but this response is also transitory. In many malaria- endemic areas of Africa, children are at risk of malaria, including severe malaria, until they are five years of age or older and to sustain protection from malaria for this period by vaccination with RTS,S/AS01E, repeated booster doses of vaccine may be required. However, there is little information about the immune response to repeated booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E. In many malaria-endemic areas of Africa, the burden of malaria is largely restricted to the rainy season and, therefore, a recent trial conducted in Burkina Faso and Mali explored the impact of repeated annual booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E given immediately prior to the malaria transmission season until children reached the age of five years. Anti-CSP antibody titres were measured in sera obtained from a randomly selected subset of children enrolled in this trial collected before and one month after three priming and four annual booster doses of vaccine using the GSK ELISA developed at the University of Ghent and, in a subset of these samples, by a multiplex assay developed at the University of Oxford. Three priming doses of RTS,S/AS01E induced a strong anti-CSP antibody response (GMT 368.9 IU/mL). Subsequent annual, seasonal booster doses induced a strong, but lower, antibody response; the GMT after the fourth booster was 128.5 IU/mL. Children whose antibody response was in the upper and middle terciles post vaccination had a lower incidence of malaria during the following year than children in the lowest tercile. Results obtained with GSK ELISA and the Oxford Multiplex assay were strongly correlated (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.93–0.95). Although anti-CSP antibody titres declined after repeated booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E a high, although declining, level of efficacy was sustained suggesting that there may have been changes in the characteristics of the anti-CSP antibody following repeated booster doses.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT03143218.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two malaria vaccines, RTS,S/AS01E and R21/Matrix-M, have recently been approved for deployment in malaria endemic areas by the World Health Organisation (WHO)1,2. The recommended dosing schedule for each vaccine is three priming doses administered one month apart, followed by a booster dose administered 12 months later. WHO has recommended that a further, seasonal booster dose may be considered in areas where malaria transmission is highly seasonal as a high level of protection is provided for only a first few months after the administration of three priming doses or a subsequent booster dose of RTS,S/AS01E3,4. In many of the areas in sub-Saharan Africa with seasonal malaria transmission, the risk of malaria, including severe malaria, remains high throughout the first five years of life. Hence, repeated booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E are likely to be required to achieve a high level of protection throughout this period of high risk. The effectiveness of this approach has been demonstrated in a trial conducted over a five-year period (2017–2021) in Burkina Faso and Mali in which children who had received three priming doses, were given three or four annual seasonal booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E with or without Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention SMC5,6. Repeated seasonal booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E were non-inferior to SMC given alone, an intervention which provides 70–80% protection against uncomplicated and severe malaria when given under trial conditions7, and the protective efficacy of the combination as compared with chemoprevention alone was 57.7% (95% CI, 53.3 to 61.7) against clinical episodes of malaria, 66.8% (95% CI, 40.3 to 81.5) against hospital admission with severe malaria, and 66.8% (95% CI, −2.7 to 89.3) against death from malaria6.

Three priming doses of RTS,S/AS01E vaccine induce a strong antibody response to the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) of Plasmodium falciparum but this wanes rapidly. A booster dose partially restores the anti-CSP antibody response but not to the level seen after the priming doses3,4. Thus, there has been concern that repeated booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E might lead to a progressive decline in antibody response and declining efficacy. In the trial of seasonal booster vaccination with the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine conducted in Burkina Faso and Mali, lower anti-CSP antibody responses were seen after first and second booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E than after the three priming doses8. Measurement of the anti-CSP antibody response to additional booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E has been undertaken to help in determination of how frequently booster doses of the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine should be given, an important issue currently being considered by the WHO and other policy making organisations and this is described in this paper.

Now that two malaria vaccines RTS,S/AS01E and R21/Matrix-M have been shown to provide an important degree of protection against clinical malaria9,10, and both have been approved by WHO1,2, malaria endemic countries are faced with a decision as to which vaccine to choose for their national programme. No head-to-head efficacy trial of the two vaccines has been conducted, and comparisons of the antibody response to the two vaccines are difficult to make because different anti-CSP antibody assays have been used in evaluation of the response to each vaccine. Most serological evaluations of the anti-CSP antibody response undertaken in clinical trials of the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine have employed an ELISA developed at the Centre for Vaccinology at Ghent University, Belgium (CEVAC) for GSK11. In contrast, a novel multiplex MSD assay developed at Oxford has been used to assess the immune response in a Phase 3 R21 clinical trial12,13. In this paper, anti-CSP antibody responses to repeated booster doses of the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine as measured using the GSK ELISA and the MSD assay are presented and compared.

Results

Study children

Children for inclusion in the serology study were selected at random by an independent statistician using systematic random sampling after sorting to give implicit stratification by age and gender as described in the methods section of the paper. On average, 150 children in the RTS,S/AS01E alone group (range per year 99–192) and 147 (range 99–193 per year) in the RTS,S/AS01E + SMC combined group were recruited to the serological sub-study each year. In each year, a small number of children in the SMC alone group (mean 30; range 19–38 between years) were recruited to determine the background titre of anti-CSP antibody resulting from natural exposure to malaria infection. Table 1 shows the number of pre- and post-vaccination paired blood samples obtained from study children by treatment arm in each year of the trial. Gender was well balanced with 50.2% of children being male and 49.8% female. Both gender and age were distributed similarly when stratified by country (Supplementary Table 1). The mean age and gender of children who were included in the sub-sample of children whose samples were tested with the Oxford MSD assay in each study year are shown by study group in Supplementary Table 2.

IgG anti-CSP antibodies titres measured by GSK ELISA following priming and booster doses and their relationship to protection against malaria infection

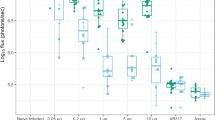

Anti-CSP ELISA IgG antibody titres measured at the CEVAC laboratory at the University of Ghent before and after priming and booster doses of the RTS,S.AS01E vaccine are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1; results stratified by country are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Geometric Mean Titres (GMTs) obtained one month after each booster dose were lower than that obtained one month after the third priming dose and declined substantially year by year; the GMT after the third priming dose was 368.9 EU/ml (95%CI, 318–428), the GMT after the first booster dose 257.5 EU/ml (95%CI, 234.6–282.7) and the GMT after the fourth booster dose 128.5 EU/ml (95%CI, 118.4–139.6). The fold ratio increase in titre after three priming doses and four subsequent booster doses (the geometric mean ratio of post – pre vaccination titre) was 446.46 (362.07 to 550.51) after the three priming doses and 5.81 (4.92–6.86), 3.87 (3.39 to 4,42), 3.47(3,14 to 3,83) and 3.18 (2.92 to 3.46) after each subsequent booster dose. A Pearson correlation analysis of the correlation between the pre- and post-vaccination log10 transformed titres was undertaken. The correlation coefficients and 95% CI for the first and successive booster doses were 0.82 (0.78 to 0.86), 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87), 0.86 (0.83 to 0.89) and 0.90 (0.88 to 0.92) respectively. It was not possible to calculate the correlation coefficient for the response to the priming dose as the standard deviation was zero. There was no difference in the pattern of antibody response between children who had received RTS,S/AS01E with or without SMC at any timepoint (Supplementary Fig. 1) and consequently these groups are combined in subsequent analyses. Responses to priming and booster doses were similar in Burkina Faso and Mali (Fig. 1), between male and female children, and between younger and older children at the time of recruitment (Fig. 2). Children in the SMC alone group had very low anti-CSP antibody titres at any timepoint and consequently are not included in the correlate of protection analyses. Comparison of the rise in anti-CSP antibody titre following vaccination as measured by the GSK ELISA across the years and by country is presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Anti-CSP IgG antibody titres as measured by the GSK ELISA in individual children pre- and post-priming vaccination (2017) and pre and post first (2018), second (2019), third (2020) and fourth (2021) booster seasonal vaccination doses shown by country. Results from Burkina Faso are shown in red, those from Mali in blue. CSP circumsporozoite, EU enzyme linked immunosorbent assay unit.

Anti-CSP antibody titres measured by the GSK ELISA in individual children pre- and post-priming vaccination (2017) and pre and post first (2018), second (2019), third (2020) and fourth (2021) booster seasonal vaccination doses are shown by country. Results from children in the Burkina Faso study are shown in red, children in the Mali study are shown in blue. The top panels show titres of male and female children, and the lower panels show titres of younger and older children (age at first vaccination). CSP circumsporozoite, EU enzyme linked immunosorbent assay unit. Only a few children who had been aged 11 months of age at the time of first vaccination were eligible for vaccination in 2021, having reached the age of five years when they were no longer eligible to receive RTS,S/AS01E or SMC in 2021. Consequently, there were only a few vaccinated children in the randomly selected group of children for the immunology serology sub-study in 2021 who had been 11 months old or older at the time of first vaccination.

The risk of clinical episodes of malaria in the year following priming and each booster dose of vaccine in relation to the anti-CSP titre at the start of the malaria transmission season is shown in Table 3 in which antibody titres are shown by tercile. Over the five years of the study, the incidence of clinical malaria was lower in children with an anti-CSP IgG antibody titre in the highest tercile compared to that in children with a titre in the lowest tercile (Incidence rate per 1000 person years at risk (PYAR), 191.6 [95%CI, 154.1–235.6] and 354 [95% CI, 301.3–413.3]) respectively. The hazard ratio of clinical malaria among children in the highest terciles versus lowest terciles of anti-CSP IgG antibody titers was 0.49 [95%CI, 0.37–0.66] (p-value <0.001). Severe malaria requiring hospital admission was infrequent in the sub-set of children in the serology sub-study (15 children) so that it was not possible to measure the potential impact of anti-CSP titre on the risk of severe malaria. Supplementary Table 5 shows the relationship between post-vaccination anti-CSP IgG antibody titre one month after priming vaccination and after each of the four booster vaccinations and the prevalence of asymptomatic malaria parasitaemia approximately five months later, at the end of the malaria transmission season. No protective effect was seen.

Reverse cumulative plots of antibody responses to primary and booster doses of vaccine are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Comparison of the incidence of clinical malaria between children with titres (as measured by GSK ELISA) above and below a putative threshold protective titre, estimated from the reverse cumulative plots as described in the methods section, were 266.8 EU/ml in 2017, 207.2 EU/ml in 2018, 157.8 EU/ml in 2019, 148.2 EU/ml in 2020 and 139.8 EU/ml in 2021 (Supplementary Table 6). Over the five years of the trial, the risk of clinical episodes of malaria was substantially less in children whose antibody titre was above the threshold than in children in whom it was below this threshold (HR 0.65 [95% C1 0,51, 0.83]).

Antibody responses in sera measured by the ELISA-based and by the Oxford MSD assay

GMTs measured by the Oxford MSD assay one month after each booster dose were lower than those obtained one month after the third priming dose and declined substantially year on year, as seen when antibody titres were measured with the GSK ELISA (Table 4). The impact of boosting on antibody response fell over time, in both Burkina Faso and Mali (Supplementary Table 7) in a similar way to that seen with the GSK ELISA (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 8).

Correlation between the results obtained with the GSK ELISA and the OXFORD MSD assay

Correlations between the GSK ELISA and the Oxford MSD assay were strong and significant at all timepoints (Fig. 3). The Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the two assays for all timepoints combined was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.93–0.95). Correlations varied from a low of r = 0.78 (95% CI, 0.72–0.83) in 2021 for the response to the fourth booster dose to a high of r = 0.98 (95% CI; 0.97–0.98) in 2017 following priming vaccination. Supplementary Table 9 presents the correlations between the two ELISA assays pre- and post- priming and pre- and post-booster vaccination by study year and country. Bland-Altman plots on log-transformed data show that the assays are generally in good agreement with most values within the agreement intervals. The mean differences were close to zero (−0.11 (95%CI, −0.13 to −0.09), with limits of agreement ranging from −0.78 to 0.56 (Fig. 4). There were very few outliers. The two assays showed more agreement on the post-priming or booster titres than on the pre-priming or booster titres, with limits of agreement ranging from −0.66 to 0.54 and −0.96 to 0.51 respectively.

Discussion

Children living in the areas of sub-Saharan Africa where malaria transmission is highly seasonal need protection against malaria until they are at least five years old and, ideally, until they are even older. SMC, now widely deployed in these areas, provides substantial protection in the region of 70–80% when given under trial conditions but SMC is demanding to deliver. Vaccination provides an alternative, or complementary approach, but because of the relatively short period of high efficacy provided by the four-dose regimen of RTS,S/AS01E3,4 subsequent booster doses will be required to provide children with a high degree of protection throughout their first decade. A high level of efficacy in the first 12 months after a first booster dose of the R21-MatrixM vaccine has been observed in a phase2 trial conducted in Burkina Faso13 and a recent modelling paper suggests that booster doses of R21-Matrix M may provide a longer period of protection than booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E14 but it is not yet known if this protection will persist until children reach the age of five years or older or whether further booster doses may be needed with this vaccine to achieve a high, sustained level of protection.

The recent study conducted in Burkina Faso and Mali has shown that a high level of protection against clinical episodes of malaria, similar to that provided by SMC, can be achieved by annual seasonal booster doses of vaccination with the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine up to the age of five years5,6. The sustained protection achieved over a five-year period was accompanied by increases in anti-CSP antibody titre following each annual booster dose, although the increase in titre post vaccination was substantially less than that seen after the three priming or first booster dose and showed a trend towards a lower response after each repeated booster dose. Despite declining post booster titres, efficacy against clinical malaria was sustained throughout the five-year period of the trial6. These findings suggest that the quality of the anti-CSP antibody may have been altered following the repeated booster doses. This may have been achieved through changes in antibody avidity and/or isotype, induction of protective antibodies binding the C terminal of the CSP molecule, antibodies binding to Fc gamma receptor promoting phagocytosis and activation of natural killer cells, or to an increase in antibodies to blood stage antigens as described in previous studies15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Some of these possibilities are currently being investigated in samples obtained during the RTS,S/AS01E + SMC trial. The RTS,S/AS01E vaccine also induces strong cell mediated immune response24,25,26,27,28,29, and interactions between antibody and cell mediated immune response have been reported30,31,32,33,34; repeated boosting with RTS,S/AS01E might enhance these interactive protective responses. Unfortunately, it was not possible to investigate this possibility in the recently completed RTS,S/SAS01E plus SMC trial but this should be explored. Because of the complexity of the immune response to malaria it is likely that no one response to the vaccine will provide a strong correlation of protection and that a combination of responses may be more powerful.

Why the antibody response to successive booster doses of RTS,S/AS01E declines is not known. The characteristics of the antibody response to a booster dose of vaccine may be influenced by a range of variables, including the age of the recipient, the construct of the vaccine, the antigen concentration of booster vaccine, the gap between priming and booster and many other variables. Why booster doses of the RTS,S/AS01E induce a lower rather than enhanced antibody response than the priming doses is not fully understood. Administration of three doses of the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine with a powerful adjuvant provides a high level of stimulation to the immune and a very high concentration of anti-CSP antibody. This may have a suppressive effect on the subsequent response to re-exposure to the same antigen, but this has not been established. Establishing the mechanism for the progressive decline in antibody response to booster doses of the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine, and possible ways in which this might be overcome, could enhance the potential of this and related vaccines to provide a longer period of protection.

Comparing serological results of trials of the RTS,S/AS01E and R21/Matrix-M vaccines has been challenging because of differences in the assays used to assess the immune response to each vaccine as well as differences in the epidemiological situations in which the trials were conducted. This study has shown that the Oxford MSD assay used to assess the anti-NANP antibody response to the R21/Matrix-M vaccine in a phase 3 trial, shows a very similar pattern in the anti-CSP antibody response to priming and boosting with RTS,S/AS01E to that observed with the GSK ELISA and a high degree of correlation was found between the two assays, as noted recently in another study35. Demonstration that this is the case will facilitate serological comparison between previous and future studies of the RTS,S/AS01E and the R21/Matrix-M vaccines. In addition, the multiplex approach allows simultaneous measurements of antibody response against the individual components of the RTS,S/AS01E and R21 antigens (central repeat region, C-terminus and HBsAg), facilitating a broader evaluation of the humoral immune response to vaccination from a small sample of serum.

As the R21/Matrix-M and RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccines become increasingly available, their use may be expanded beyond young children to other at-risk populations and in elimination campaigns. Standardisation of the methods of measurement of the antibody response to the vaccines in these different situations will be important in interpretation of the findings across these studies.

Methods

Details of the trial during which the blood samples for the serological assays described in this paper were collected have been described previously5,6 and serological results obtained during the first three years of the study have also been reported8.

Overall trial design, study sites and study populations

The RTS,S/AS01E + SMC trial was designed to determine whether seasonal vaccination with the RTS,S/AS01E malaria vaccine was non-inferior to SMC in preventing clinical episodes of malaria and/or whether the combination was superior to either intervention given alone. The primary trial endpoint was the incidence of uncomplicated clinical malaria, defined as an episode of fever (temperature ≥ 37.5 °C or a history of fever within the past 48 h), and microscopically confirmed P. falciparum parasitaemia at a density of 5000 parasites per µl or more in a child who presented to a health centre for treatment5,6 .

The trial was conducted in Bougouni and Ouélessébougou districts, Mali and in Houndé district, Burkina Faso. All households within the study areas with children aged 5–17 months on April 1st, 2017, were enumerated in February-March 2017. Eligible children whose parent or guardian provided written, informed consent for their child to join the trial were allocated randomly to an SMC alone, RTS,S/AS01E alone, or to a combined SMC + RTS,S/AS01E group by an independent statistician using permuted blocks after assorting according to age, sex, area of residence and previous receipt of chemoprevention5,6.

Children in the RTS,S/AS01E alone or RTS,S/AS01E + SMC group received three doses of RTS,S/AS01E vaccine (GSK, Rixensart, Belgium) at monthly intervals in April - June 2017 followed by seasonal booster doses in June 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, prior to the malaria transmission season (Fig. 5). Children in the SMC alone group received three doses of rabies vaccine (RabipurR) (Bavarian Nordic A/S, Denmark) in 2017, a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine (HAVRIXR)) (GSK, Rixensart, Belgium) in 2018 and 2019 and booster doses of tetanus or tetanus-diphtheria toxoid vaccine in 2020 and 2021. The RTS,S/AS01E + SMC and the SMC alone groups received four cycles of SMC with sulphadoxine pyrimethamine and amodiaquine (SPAQ) at monthly intervals each year until they reached the age of five years; children in Burkina Faso received an additional round of SMC in the last year of the study in line with national guidelines. Children in the RTS,S/AS01E alone group received matching SMC placebo (Supplementary Table 10). All study children were given a piperonyl butoxide long lasting insecticide treated bednet at enrolment in 2017 and again in 2020.

Project staff based in study health facilities identified and treated all cases of malaria who presented at these facilities, using a Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT), and obtained a blood film for subsequent microscopy. All admissions of study children to hospital were documented by trial staff. A cross-sectional survey for malaria prevalence was undertaken in all study children one month after the last round of SMC administration each year. Blood films were read by two independent microscopists and, in instances of a discrepancy in positivity or density, by a third reader with discrepancies resolved as described previously36.

Serology

Children for inclusion in the serology study were selected at random by an independent statistician using systematic random sampling after sorting to give implicit stratification by age and gender. The same children were sampled pre- and post-vaccination within a study year, but different children were selected each year to avoid repeat venous blood sampling of the same child over successive years.

GSK ELISA standardised ELISA

Anti-CSP IgG antibody titres were measured by a standardised ELISA at the CEVAC laboratory Ghent University, Belgium11. This assay measures IgG responses to the R32LR protein which comprises two NVDP oligopeptides and thirty NANP repeats linked to the dipeptide Leu-Arg (NVDP[NANP]152LR). The lower limit of quantification for this assay is 1.9 EU/ml and samples with a titre below this lower limit (i.e., titre with a value of 0) were assigned a titre of 0.95 EU/ml, half the lower limit of detection.

NANP multiplexed ASSAY (Oxford MSD assay)

A multiplexed assay (Oxford MSD assay) was developed by Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) and validated at the Jenner Institute, Oxford (manuscript under review). The assay simultaneously measures antibody responses to six repeats of the four-amino acid central repeat region of CSP (NANP6) in addition to the C-terminus of CSP, the full-length R21 vaccine antigen including NANP6, the C-terminus and Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), which is present in both RTS,S and R2112. The lower limit of quantification for this assay was 319 AU/ml and samples with a titre below this lower limit (i.e. titre with a value of 0) assigned a titre of 159.5 AU/ml, half the lower limit of detection. Staff undertaking the serological assays were blinded to the study group from which a sample came.

Sample size and statistical analyses

The RTS,S/AS01E + SMC trial recruited 6863 children (approximately 2000 in each group). Based on findings in previous RTS,S/AS01E trials, it was estimated that inclusion of approximately 150 children in each country at each time point would give a study with 80% power to detect a difference of 25% in GMT between two comparison groups. For comparison of the GSK ELISA with NANP6 IgG measured by the Oxford MSD ELISA, a random sample of approximately 50 serum samples was selected from within each of the groups of children who had received the RTS,S/AS01E vaccine and whose samples had been tested with the GSK ELISA.

Descriptive statistics means (standard deviations) and proportions were used to summarise demographic characteristics of children in each treatment group by year. Pre-vaccination and post-vaccination titres in each year of the study among children who received RTS,S/AS01E were calculated, and geometric means and 95% confidence intervals determined. Ratios of geometric means and 95% confidence intervals were used to compare pre- and post-vaccination titres and the rise in titre after each booster dose, adjusting for SMC treatment in the combined RTS,S/AS01E + SMC group.

Cox regression models were used to compare the incidence of morbidity outcomes in relation to antibody response, measured using the GSK ELISA assay, defined by terciles of the anti-CSP titres using a robust standard error to account for multiple episodes per child37. Reverse cumulative plots were used to define a potential cut-off titre associated with protection against episodes of clinical malaria38. The threshold titre was defined as the minimum titre measured in X% of children who received RTS,S/AS01E, where X% was the efficacy of RTS,S/AS01E against clinical malaria in that year of the study. Based on these thresholds, incidence rates of clinical malaria in children with antibody titres below and above the threshold were compared in each of the study years. Poisson regression models using robust standard errors39 were used to estimate and compare the prevalence of P. falciparum infection at the end of the malaria transmission season in relation to antibody response defined by terciles of the anti-CSP titres, measured using the GSK ELISA. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and 95% Confidence intervals were used to compare the two ELISA assays. To assess agreement between assays, the limits of agreement method of Bland and Altman was used40. As the units were arbitrary, each assay was first standardised by subtracting its mean and dividing by the standard deviation before applying the Bland and Altman method. There was no prespecified criteria for acceptable limit of agreement for the two assays.

Ethics and trial oversight

The trial protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the Ministry of Health, Burkina Faso, the University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako, Mali and the trial approved by the national regulatory authorities of Burkina Faso and Mali. The trial’s Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed serious adverse events, approved the statistical analysis plan and archived the locked databases prior to unblinding. A steering committee gave scientific advice and monitored progress of the trial. Written, informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all children in the trial at the start of the trial and at the start of the two-year extension period. The trial is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03143218).

Data availability

Individual de-identified data on trial participants that were used to produce this paper, the data dictionary, protocol and the statistical analysis plan will be made available to qualified investigators following a request for use of these data which will be held at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (https://datacompass.lshtm.ac.uk/). Data will be available from twelve months following the date of publication. Requests for access to trial data and request should be addressed to the corresponding author (brian.greenwood@lshtm.ac.uk).

References

WHO. WHO recommends ground breaking malaria vaccine for children at risk; Historic RTS, S/AS01 recommendation can reinvigorate the fight against malaria. https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2021-who-recommends-groundbreaking-malaria-vaccine-for-children-at-risk (2021).

WHO. WHO recommends R21/Matrix-M vaccine for malaria prevention in updated advice on immunization. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-10-2023-who-recommends-r21-matrix-m-vaccine-for-malaria-prevention-in-updated-advice-on-immunization (2023).

White, M. T. et al. A combined analysis of immunogenicity, antibody kinetics and vaccine efficacy from phase 2 trials of the RTS, S malaria vaccine. BMC Med 12, 1–11 (2014).

White, M. T. et al. Immunogenicity of the RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine and implications for duration of vaccine efficacy: secondary analysis of data from a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 15, 1450–1458 (2015).

Chandramohan, D. et al. Seasonal malaria vaccination with or without seasonal malaria chemoprevention. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1005–1017 (2021).

Dicko, A. et al. Seasonal vaccination with RTS, S/AS01E vaccine with or without seasonal malaria chemoprevention in children up to the age of 5 years in Burkina Faso and Mali: a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, 75–86 (2024).

ACCESS-SMC Partnership. Effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention at scale in west and central Africa: an observational study. Lancet 396, 1829–18440 (2020).

Sagara, I. et al. The anti-circumsporozoite antibody response of children to seasonal vaccination with the Rts, S/As01e malaria vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, 613–622 (2022).

Asante, K. P. et al. Feasibility, safety, and impact of the RTS, S/AS01E malaria vaccine when implemented through national immunisation programmes: evaluation of cluster-randomised introduction of the vaccine in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi. Lancet 403, 1660–1670 (2024).

Datoo, M. S. et al. Safety and efficacy of malaria vaccine candidate R21/Matrix-M in African children: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 403, 533–544 (2024).

Clement, F. et al. Validation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the quantification of human IgG directed against the repeat region of the circumsporozoite protein of the parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Malar. J. 11, 1–15 (2012).

Venkatraman, N. et al. Phase I assessments of first-in-human administration of a novel malaria anti-sporozoite vaccine candidate, R21 in matrix-M adjuvant, in UK and Burkinabe volunteers. medRxiv. 19009282, https://doi.org/10.1101/19009282 (2019).

Datoo, M. S. et al. Efficacy and immunogenicity of R21/Matrix-M vaccine against clinical malaria after 2 years’ follow-up in children in Burkina Faso: a phase 1/2b randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1728–1736 (2022).

Schmit, N. et al. The public health impact and cost-effectiveness of the R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, 465–475 (2024).

Olotu, A. et al. Avidity of anti-circumsporozoite antibodies following vaccination with RTS, S/AS01E in young children. PLoS One 9, 115126, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115126 (2014).

Chaudhury, S. et al. The biological function of antibodies induced by the RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine candidate is determined by their fine specificity. Malar. J. 15, 1–12 (2016).

Dennison, S. M. et al. Qualified biolayer interferometry avidity measurements distinguish the heterogeneity of antibody interactions with Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein antigens. J. Immunol. 201, 1315–1326 (2018).

Dobano, C. et al. Concentration and avidity of antibodies to different circumsporozoite epitopes correlate with RTS, S/AS01E malaria vaccine efficacy. Nat. Commun. 10, 2174, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10195-z (2019).

Thompson, H. A. et al. Modelling the roles of antibody titre and avidity in protection from Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection following RTS, S/AS01 vaccination. Vaccine 38, 7498–74507 (2020).

Suscovich, T. J. et al. Mapping functional humoral correlates of protection against malaria challenge following RTS, S/AS01 vaccination. Sci. Transl. Med 12, abb4757, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abb4757 (2020).

Kurtovic, L. et al. Multifunctional antibodies are induced by the RTS, S malaria vaccine and associated with protection in a phase 1/2a trial. J. Infect. Dis. 224, 1128–1138 (2021).

Seaton, K. E. et al. Subclass and avidity of circumsporozoite protein specific antibodies associate with protection status against malaria infection. NPJ Vaccines 6, 110 (2021).

Dobaño, C. et al. RTS, S/AS01E immunization increases antibody responses to vaccine-unrelated Plasmodium falciparum antigens associated with protection against clinical malaria in African children: a case-control study. BMC Med 17, 1–19 (2019).

Lalvani, A. et al. Potent induction of focused Th1-type cellular and humoral immune responses by RTS, S/SBAS2, a recombinant Plasmodium falciparum malaria vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 1656–1664 (1999).

Sun, P. et al. Protective immunity induced with malaria vaccine, RTS, S, is linked to Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 171, 6961–6967 (2003).

Pinder, M. et al. Cellular immunity induced by the recombinant Plasmodium falciparum malaria vaccine, RTS, S/AS02, in semi-immune adults in The Gambia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 135, 286–293 (2004).

Barbosa, A. et al. Plasmodium falciparum-specific cellular immune responses after immunization with the RTS, S/AS02D candidate malaria vaccine in infants living in an area of high endemicity in Mozambique. Infect. Immun. 77, 4502–4509 (2009).

Olotu, A. et al. Circumsporozoite-specific T cell responses in children vaccinated with RTS, S/AS01E and protection against P falciparum clinical malaria. PLoS One 6, e25786, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025786 (2011).

Moncunill, G. et al. RTS, S/AS01E malaria vaccine induces memory and polyfunctional T cell responses in a pediatric African phase III trial. Front Immunol. 8, 1008, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01008 (2017).

Ndungu, F. M. et al. A statistical interaction between circumsporozoite protein-specific T cell and antibody responses and risk of clinical malaria episodes following vaccination with RTS, S/AS01E. PLoS One 7, 52870, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052870 (2012).

White, M. T. et al. The relationship between RTS, S vaccine-induced antibodies, CD4+ T cell responses and protection against Plasmodium falciparum infection. PLoS One 8, 61395, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061395 (2013).

Pallikkuth, S. et al. A delayed fractionated dose RTS, S AS01 vaccine regimen mediates protection via improved T follicular helper and B cell responses. Elife 9, 51889, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.51889 (2020).

Kazmin, D. et al. Systems analysis of protective immune responses to RTS, S malaria vaccination in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2425–2430 (2017).

Young, W. C. et al. Comprehensive data integration approach to assess immune responses and correlates of RTS, S/AS01-mediated protection from malaria infection in controlled human malaria infection trials. Front. Big Data. 4, 672460, https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2021.672460 (2021).

Mugo, R. M. et al. Correlations between three ELISA protocols measurements of RTS, S/AS01-induced anti-CSP IgG antibodies. PLOS One 18, 0286117, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286117 (2023).

Swysen, C. et al. Development of standardized laboratory methods and quality processes for a phase III study of the RTS, S/AS01 candidate malaria vaccine. Malar. J. 10, 1–8 (2011).

Xu, Y., Cheung, Y., Lam, K., Tan, S. & Milligan, P. A simple approach to the estimation of incidence rate difference. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172, 334–343 (2010).

Siber, G. R. et al. Estimating the protective concentration of anti-pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide antibodies. Vaccine 25, 3816–3826 (2007).

Zou, G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159, 702–706 (2004).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1, 307–310 (1986).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the Trial Steering Committee (Feiko ter Kuile [chair], Kwadwo Koram, Mahamadou Ali Thera, Joaniter Nankabirwa, Morven Roberts and Caroline Harris) and the members of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (Blaise Genton [chair], Sheick Coulibaly, Umberto D’Alessandro, Francesca Little, Jean Louis Ndiaye and the late Malcolm Molyneux) for their support and advice which led to the successful conclusion of this study. They thank Sibyl Couvent, Sofie Librecht, Peter Vander Linden, and Gwenn Waerlop at Center for Vaccinology (CEVAC), the University of Ghent, for performing the GSK assay in Belgium, Aurelio Di Pasquale, Swiss Tropical Public Health Institute for helping in the design of the electronic CRFs in ODK and hosting the database and Karen Slater for supporting the trial in many ways, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA for donating the RTS,S/AS01E and HAVRIX vaccines, Birkhäuser + GBC AG, Switzerland for supplying identity cards and labels, Guilin Pharmaceuticals for supplying the drugs for Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention, the Ministry of Health staff in the Bougouni, Ouélessébougou, and Houndé districts for their assistance with running the trial, and all of the caretakers and children for their participation. The overall trial on which this serology study was based was funded by the UK Joint Global Health Trials (Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Wellcome Trust (WT) (grant MR/V005642/1). This UK funded award was part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union. The trial was also funded by PATH’s Malaria Vaccine Initiative (CVIA 083-MAL99) through a grant to PATH (INV-007217) from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Research grants were made to the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, with sub-contracts to the Malaria Research and Training Center (MRTC), Mali, the Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé (IRSS) and to the University of Oxford.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. and S.P.M. were responsible for the serological analyses conducted at Oxford. S.A. and L.S. undertook the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. P.S. was responsible for the overall data management programme. In Burkina Faso, J.B.O., H.T. and I.Z. were responsible for overall management and oversight of the trial, R.S.Y. was responsible for data and laboratory sample collection and management, F.N., and F.S.C.Z. were responsible for data collection and A.H., and A.A.S., were responsible for data management. In Mali IS, A Djimde and A Dicko were responsible for overall management and oversight of the trial, A.M., and A.T., were responsible for data and sample collection, M.D., D.I., K.S., M.K., S.T., O.M.D., Y.K., H.Y., and K.D. were responsible for data collection and IT for data management. D.C., B.G., C.L., C.O., K.E. and O.O. contributed to the overall trial oversight and management. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. No paid support was employed in writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

O.O. and K.E. are employees of the GSK group of companies and have restricted shares in the GSK group of companies. K.E. is a named inventor on patents relating to the R21/matrix M vaccine. A Dicko. reports a research grant from Grand Challenges Canada to test safety and efficacy of the PfSPZ vaccine for pregnant women and unborn children and a research contract with Oxford University to conduct a phase 3 randomized, controlled multicentre trial to evaluate the efficacy of the R21/Matrix-M vaccine in African children against clinical malaria outside of the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, M.S., Stockdale, L., Sagara, I. et al. The anti-circumsporozoite antibody response to repeated, seasonal booster doses of the malaria vaccine RTS,S/AS01E. npj Vaccines 10, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01078-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01078-0