Abstract

Systemic candidiasis inflicts ~1.2 million deaths annually worldwide. Despite its severity, an approved antifungal vaccine remains an unmet human need. In a quest to design a live-whole cell vaccine, we characterized and demonstrated the vaccine potential of two dual DNA polymerase-defective strains of Candida albicans. While the deletion of POL32 in a hyper-virulent rad30ΔΔ strain attenuated the virulence, the deletion of RAD30 in an avirulent pol32ΔΔ did not revert to a hypervirulence phenotype. Both the dual polymerase-defective strains replicate transiently in the host and trigger immune responses to prevent reinfections in mice by employing a concerted involvement of innate, adaptive, and trained immunity. The cellular and molecular depletion in immunized mice suggested the role of B- and T-cells, neutrophils, and macrophages in antifungal immunity. Altogether, our results confirmed that Pol32 is a true virulence factor and intravenous vaccination with these attenuated strains could prevent systemic candidiasis in the preclinical models without evident safety concerns; thus, these candidate strains have enormous translational potential to fully develop as antifungal vaccines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Candida albicans, along with non-albicans Candida species like C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. auris, etc., constitute a notorious group of fungal pathogens in humans as they colonize both external and internal organs, leading to candidiasis1,2. More importantly, some of these even co-exist and co-evolve with the human host as commensals, and regulate host physiology and immunity3. While their overgrowth on mucosal layers causes treatable superficial candidiasis, systemic candidiasis is more prevalent in immunocompromised hosts and is accountable for a higher rate of morbidity and mortality. Relating to disease incidence, suffering, fatalities, and economic burden, the impact of candidiasis is alarmingly high, making it an unrelenting global healthcare challenge4. The global prevalence of invasive candidiasis is close to 1.7 million individuals per year, while the mortality rate approximates 60% which is more than the deaths due to malaria or breast or prostate cancer, and is very similar to those caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or HIV4,5. The current treatment modalities mostly depend on antifungal drugs from the classes azoles, polyenes, and echinocandins6. However, they are prescribed cautiously due to associated cytotoxicity, adverse side effects, and emergence of resistance. Moreover, anti-fungal vaccines remain an unmet human need so far. Realizing the threats, WHO enlisted a catalog of 19 fungi, including species from Candida, as “critical pathogens” and emphasized the urgent need for early diagnostics, potent antifungal drugs, and effective immunotherapeutics and prophylactics7.

Designing and developing vaccines against fungal pathogens has primacy. Several studies on host-fungal interactions led to the identification of several experimental vaccines, and those were shown to prevent different types of candidiasis in animal models, albeit with varying efficacies. Two of the subunit vaccines, NDV-3A (Als3) and PEV7 (Sap2), are in different phases of clinical trials and reported to protect against recurrent superficial vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) with different effectiveness. Not a single vaccine candidate has been explored in clinical trials yet against systemic candidiasis. Our approach has been to design live whole cell vaccines by targeting DNA replication machinery2,8,9,10,11,12. All pathogens need to replicate in the host to survive and cause infections. Therefore, essential biological processes like DNA replication are suitable targets for designing drugs and vaccines against a pathogen. A recent study revealed that by sequestering divalent metals that are essential cofactors of various critical enzymes, including DNA polymerases, by EDTA, the growth and virulence of C. albicans can be suppressed both in vitro and in vivo11,13. The Candida genome database suggests that there are seven DNA polymerases (Pol) in C. albicans, and few of them have only been verified8,9,10,14,15. Three essential replicative DNA polymerases, Polα, Polδ, and Polε, coordinately complete DNA synthesis during genome replication16,17. While Polε synthesizes leading strand DNA, Polδ is engaged in both lagging and leading strands of DNA replication18. Both Polδ and Polε subunits of C. albicans have been verified6,9,10. Deletion of the nonessential subunits in these DNA polymerases led to the attenuation of the virulence of C. albicans. While the C. albicans strain deficient in the Pol32 subunit of Polδ exhibits temperature sensitivity at 42 °C, deletion of individual and both of the DPB3 and DPB4 of Polε caused growth defects at 37 °C. Immunization and pathogenic re-challenge experiments in pre-clinical models revealed that Polδ defective strains prevent fungal re-infections but not the Polε defective attenuated strain10,12. This result confirmed that a whole-cell attenuated strain that can replicate in the host can only boost immune responses and protect mice from re-infection. To strengthen our observations and to establish Pol32 as a virulence factor, we decided to delete POL32 in a hyper-virulent C. albicans strain and to determine its vaccine efficacy and mechanism of protective immunity.

DNA polymerase eta (Polη), encoded by RAD30, is involved in translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) of cyclobutane-pyrimidine dimers and other DNA lesions, and its absence in C. albicans cells results in sensitivity to various DNA-damaging agents15. TLS is a process by which DNA with lesions can be bypassed, involving specialized DNA polymerases. DNA replication by Polδ/Polε and TLS by Polη are parallel pathways that coordinately operate to stabilize the cell’s genome. In our earlier study, we found that the C. albicans strain without Polη (rad30ΔΔ) is relatively more virulent than its isogenic parental strain8. We generated two double-DNA polymerase knockout strains where both RAD30 and POL32 genes were deleted in different orders, and their safety and vaccine efficacy were determined. Here, we showed that both the dual DNA polymerase defective strains (rad30ΔΔpol32ΔΔ and pol32ΔΔrad30ΔΔ) were avirulent, attributing to POL32’s function and activating cell-mediated and trained immunity to protect against re-infections.

Results

Double-deletion of RAD30 and POL32 genes sensitizes C. albicans cells to genotoxic agents

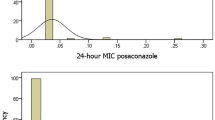

During TLS, Polη incorporates nucleotide opposite DNA lesions at the site of stalled replication, and then Polζ and (/or) Polδ extend to complete the DNA synthesis process19. Accordingly, loss of Polη and (/or) Pol32 enhances cytotoxicity caused by various DNA-damaging agents like UV, cisplatin, Methyl methane sulfonate (MMS), and tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP)9,15. In addition, the deletion of Pol32, being a component of replicative DNA polymerase Polδ, causes sensitivity to hydroxyurea (HU) and an elevated temperature, like 42 °C. To generate strains that are defective in both DNA replication and translesion DNA synthesis, POL32 and RAD30 genes were deleted from rad30ΔΔ (CNA7) and pol32ΔΔ (CNA25) backgrounds, respectively, and characterized (Supp. Fig. 1Ai–ii). The resultant dual DNA polymerase defective strains rad30ΔΔpol32ΔΔ (CNA24) and pol32ΔΔrad30ΔΔ (CNA298) shared phenotypes with the individual knockout strains (Fig. 1A, B). Although the dual-Pol deletion strains did not show any growth defect at normal physiological conditions, similar to CNA25, they were temperature sensitive at 42 °C and showed retarded growth in the presence of HU (Fig. 1Bi–ii). Moreover, the double-deletion strains were hypersensitive to MMS, TBHP, Cisplatin, and UV, which suggests that defective parallel pathways of genome stability in C. albicans exhibited synergistic phenotypes (Fig. 1Biii–vi). Both CNA24 and CNA298 replicate normally, but only under stress conditions, their growth is affected.

A A liquid growth curve was carried out from the overnight grown cultures of WT (Pink), rad30ΔΔ (purple), pol32ΔΔ (green), rad30ΔΔpol32ΔΔ (blue), and pol32ΔΔrad30ΔΔ (orange) in 10 mL YPD broth. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm wavelength for 14 h at an interval of 2 h. The experiments were performed twice with technical triplicates and the result was represented as mean ± SEM. The OD values were plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0. B Susceptibility of the above-mentioned strains to (i) temperature (16 °C, 30 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C), (ii) HU, (iii) MMS, (iv) TBHP, (v) Cisplatin and (vi) UV by spot dilution assay. The well-grown culture plates were photographed in the ChemiDoc image system.

CNA24 and CNA298 exhibit altered colony morphology and reduced filamentation with modified cell wall architecture

C. albicans is a multimorphic fungus that alters its shape from round to pseudohyphae to hyphae in response to stress conditions, and in the presence of serum, it develops a germ tube. The morphological transition of C. albicans is associated with virulence20. Both RAD30 and POL32 deficient strains of C. albicans exhibit reduced filamentation in the presence of serum8,9. To check any alteration in the morphology of CNA24 and CNA298 due to the loss of both RAD30 and POL32 genes, cells were grown in the YPD + 10%FBS at 37 °C and after 1 h, observed under the microscope. While WT cells produced longer germ tubes, similar to CNA7 and CNA25, the germ tubes of CNA24 and CNA298 were stunted (Fig. 2Ai–ii). For further confirmation, WT and CNA24 cells were spotted on a solid YPD plate containing 10% FBS and a plate with only 10% FBS, and incubated for 48 and 96 hours (hrs), respectively. While the WT colony was wrinkle-shaped, the colony of CNA24 was relatively smooth and round-shaped due to a lack of filamentation and an inability to show invasive growth. Cells were picked up from the plate, and the filamentation status was confirmed by microscopic observations (Supp. Figure 1Bi–ii). Next, to check the cell wall architecture, cells were imaged under transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Interestingly, the cell wall of CNA24 was relatively thicker than WT and CNA7 cells (Fig. 2B). The average thickness of the cell wall of WT and CNA7 cells was ~100–120 nm, whereas it was almost doubled in CNA24 ( ~ 200–225 nm). Interestingly, the cell wall thickness in CNA24 was due to a higher content of β-glucan. The β-glucan layer is juxtaposed between the upper layer of mannan and the chitin-rich inner layer, and these molecules are critical for immune cell recognition21. More chitin in the cell wall of CNA7 was observed (Fig. 2C and Supp. Figure 1C iii). Since these dual DNA polymerase-defective mutants exhibited compromised filamentation and altered cell wall architecture, it was intriguing to determine their virulence potential.

A C. albicans strains WT, CNA7, CNA25, CNA24, and CNA298 were grown in YPD liquid media + 10% FBS for 1 h at 37 °C and morphology was captured under the Leica DM 500 microscope with scale bar-10µm (i). The length of germ tubes was measured using ImageJ software and represented as mean ± SEM in dot plots in Graph Pad Prism 8.0. The statistical significance of knockout strains in comparison to WT was determined by one-way ANOVA (ii). B Ultrastructure of the WT, CNA7, and CNA24 were determined using TEM. Images depicting a group of cells, scale bar = 2 μm (2500X) (i), an individual cell, scale bar = 1 μm (5000X) (ii), and the thickness of individual cell wall, scale bar = 500 nm (10000X) (iii) are given. The arrow marks the zoom-in image of the cell to be examined. The box indicates the zoom-in image of the fraction of the cell wall to calculate the actual thickness. The graph was plotted using mean ± SEM in Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software. Statistical significance of knockout strains in comparison to WT was determined by using by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. C The chitin, β-glucan, and mannan contents of the cell wall were estimated by staining with CFW, aniline blue, and Con A, respectively, using flow cytometry. The graph was plotted using mean fluorescence intensity and statistical significance was determined between WT and mutant strains using a two-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. The results are presented as mean ± SEM from triplicate data using Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software. Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, and ****p ≤ 0.0001).

CNA24 and CNA298 are attenuated strains and protect mice from C. albicans reinfection

While the RAD30 deletant was hyper-virulent, the POL32 null strain was avirulent in the mice model of systemic candidiasis. We argued that the different order of deletion of these genes might impact Candida pathogenesis differently. First, to check the virulence potential of CNA24, fungal interaction with macrophages in a co-culture experiment was carried out to measure the efficiency of phagocytosis, fungal killing by immune cells, and immune evasion ability of the pathogen (Fig. 3). The deep red-stained murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells and C. albicans cells stained with Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) were co-cultured in a 1:1 ratio, and cells were recovered for flow cytometry at the mentioned periods. Applying proper gating strategy, macrophage up-taking fungal cells (double stain-positives in Q2 as opposed to Q1 and Q4 as single dye stained, and Q3 as unstained cells) were sorted and estimated (Fig. 3A). We observed that about 90% of WT fungal cells were up taken by the RAW 264.7 cells within 1 h of co-culturing that was subsequently reduced to ~82% in 3 h of incubation. However, the efficiency of phagocytosis was found to be ~86–65% when CNA24 was mixed with macrophages. This indicated that the rate of phagocytosis is almost similar for both WT and CNA24, although the reduced population of double-stained positive cells in later time points in such co-culture experiments could be due to the clearance of fungal cells by macrophages and vice versa. To verify, the C. albicans colony-forming unit (CFU) efficiency of the co-cultures was determined, and a faster clearance of CNA24 than the WT cells was quite evident (Fig. 3B). Conversely, a higher population of macrophage cells was PI positive, indicative of macrophage death, when RAW 264.7 cells were co-cultured with WT than with CNA24 (Fig. 3Ci–ii). Altogether, this data indicated that CNA24 could be attenuated of virulence and it cannot evade the host’s immune system. Next, we used systemic candidiasis mouse models to confirm the virulence potential of these strains by infecting BALB/c mice (n = 8) intravenously with fungal cells (5 × 105 CFU/mouse). Hematogenously disseminated candidiasis leads to multi-organ sepsis and death in animals, a condition very similar to systemic candidiasis in humans. Mice showing humane endpoints due to fungal infections were euthanized, and that period was considered the death time. While upon intravenous (IV) challenge with wild type C. albicans, mice succumbed to infection within 7 days of inoculation, the CNA24 and CNA298 challenged mice groups did not show any morbidity and noticeable symptoms (p = 0.0001), and thus they survived similarly to the saline control group (pink vs blue, orange, and cyan lines, Fig. 3D). This result further confirmed that irrespective of order of genes deletion, both CNA24 and CNA298 strains are avirulent. While the deletion of POL32 could alter the phenotype of a hyper-virulent strain like rad30ΔΔ (CNA7) to avirulent, the deletion of RAD30 could not modify the characteristics of pol32ΔΔ. It seems that the Pol32’s function is predominant over Rad30 even in fungal pathogenesis.

A Deep red-stained RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells were co-cultured with CFSE labeled WT and CNA24 strains of C. albicans in a 1:1 ratio for consecutive 3 h to determine macrophage-fungal cell interaction. At a regular interval of 1 h, cells were pooled and acquired, and double-positive cells (Deep Red-APC channel and CFSE-FITC channel; Q2, P3) were acquired by flow cytometry using proper gating strategy and analyzed by FlowJo software. B The phagocytosed WT (Pink) and CAN24 (blue) cells were lysed out of the macrophages from the co-culture experiment after 1 h intervals and lived C. albicans cells were estimated by CFU counts. The graph was plotted using mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was determined by using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests. C To determine the macrophage death, PI staining microscopy images of macrophages from the co-culture experiment using an EVOS imaging system (10X) with a 300 μm scale bar are shown (i). The graph was plotted using mean ± SEM of PI-stained macrophages from five biological replicates of WT (Pink) and CNA24 (blue) independent co-cultures. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test (ii). Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (**p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, and ns- not significant). D Male BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks, n = 8) were subjected to primary injection with WT along with saline control. Survivability was monitored for 30 days. A similar set of mice was injected with saline and 5 × 105 CFU/mice of CNA24 and CNA298 intravenously (1°), and after 30 days they were reinjected with WT (5 × 105 CFU/mice) as a secondary challenge (2°). Survivability was monitored for 30 days. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve was plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software using the Mantel–Cox test and comparative p values were mentioned in the graph. E PAS staining images of kidneys from each mice group (n = 2) that succumbed to infections (WT, 1°Saline-2°WT, 1°CNA24-2°WT, 1°CNA298-2°WT) were captured under a light microscope (Leica DM 500) using LAS EZ 2.1.0 software at 40X with 10 μm scale bar. The arrow indicates the fungal cells in respective kidney sections. F CFU counts of C. albicans in the kidney, liver, and spleen were determined to measure fungal burden. The graph was plotted by taking mean ± SEM using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

To check the vaccine efficacy of CNA24 and CNA298 strains, groups of BALB/c mice (n = 8) were immunized intravenously with these (5 × 105 cells per mouse) or 100 μl of saline per mouse as a control, and after 30 days, they were re-challenged with WT C. albicans (5 × 105 cells per mouse), and their survivability was monitored. Interestingly, while the sham immunized mice succumbed to infections by WT C. albicans within 8 days (1°Saline-2°WT), 60% of re-challenged CNA24 and CNA298 immunized mice were protected (1°CNA24-2°WT and 1°CNA298-2°WT). This result suggested that CNA24 and CNA298 strains being avirulent provide considerable protection against reinfection (p = 0.0003 to 0.001). To confirm the vaccine efficacy result, the experiment was repeated using CNA25 as a positive control, and an almost similar result was obtained (Supp. Figure 2A–B). Although we observed IV immunization to be safe, we wanted to verify the vaccine efficacy of CNA24 by the subcutaneous (SC) route as well. After 30 days of SC immunization either with a single or a double dose of CNA24 (5 × 105 cells per mouse), mice were re-infected with wild type C. albicans (IV, 5 × 105 cells per mouse). The survival curve suggested that SC immunization of CNA24 did not prevent candidiasis, and mice succumbed to re-infection, although a delay in death time was noticed upon double-dose vaccination (Supp. 2C i). The organ pathology was checked for the deceased mice of all groups, and fungal sepsis in the kidneys was confirmed by CFU and PAS staining of kidney tissues (Fig. 3E–F; Supp. 2Cii–iii). Thus, the IV route of immunization was followed henceforth. The mice that survived from the saline and immunized groups were allowed to live for another 6 months, and then the experiment was terminated. Since CNA24 and CNA298 behaved similarly, to minimize animal usage, only CNA24 was further characterized.

Reduced fungal burden and enhanced expression of pattern recognition receptors in infected organs of CNA24-challenged mice

Since WT and the dual DNA polymerase defective strains replicate similarly under normal physiological conditions, to compare their in vivo proliferation status, a time kinetics experiment was conducted to measure the fungal load in vital organs as depicted in Fig. 4A. Various tissues were collected after sacrificing the mice (n = 8) in each mentioned time points and fungal CFU with respect to time among the mice groups was determined (Fig. 4B). Within 3 h of inoculation, the fungal load in the kidney, lungs, and brain tissues was very high in WT infected mice (pink line) than in the CNA24 challenged mice group (blue line). While the load further increased to a maximum in 7 days of infected kidneys with WT C. albicans, it subsided to almost negligible counts in all the tissues within 15 days in the CNA24-challenged mice group. There was a marginal reduction in fungal load in infected lungs and brains from 3 h to 7 days of WT inoculation. Since no or minimal number of mice survived upon WT C. albicans infections from 7 days to the next sacrifice period of 15 days, we considered this fungal burden as a threshold load to cause sepsis leading to death (Fig. 4B i). However, the CNA24 cells were less proliferative than WT in mice, and they were cleared from the system, allowing mice to survive. Interestingly, in the WT re-challenged CNA24-vaccinated mice group (1°CNA24-2°WT, maroon line), the fungal load in essential organs gradually reduced to a negligible level from 3 h to 30 days, while no fungal cells in lungs and brains were detected post 15 days (Fig. 4Bii–iii). This result suggested that a slower proliferation of CNA24 cells is good enough to activate robust protective immune responses for efficient clearance of pathogenic fungal cells, leading to mice survival. Saline control groups did not show any fungal load at any given time. CFU analyses of kidneys of various groups of animals were further authenticated by PAS staining, and only the primary WT-challenged group mice kidneys showed the presence of C. albicans cells, and due to low or negligible fungal load in other groups of mice, C. albicans cells were not detected (Supp. Figure 2D).

A A schematic presentation depicts the experimental design of kinetic analyses. As shown pool of primary and secondary challenged mice groups were generated. Mice euthanization (8 mice per time point) at indicated time points (3 h, 3 d, 7 d, 15 d, and 30 d) in both pre- and post-immunization groups was carried out. The blood and tissues like the brain, spleen, lungs, and kidneys were collected for various analyses at each time point from all the mice after euthanization. The image was generated using BioRender. B Fungal burden was determined at the mentioned time points from different vital organs like kidney (i), lungs (ii), and brain (iii) by spreading a specific dilution of the tissue homogenate on YPD agar + chloramphenicol plates. The multi-colored line graph was plotted using Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software depicting the CFU of each group (WT-Pink, CNA24-blue, Saline-cyan, 1°Saline-2°Saline- purple and 1°CNA24-2°WT-maroon) at mentioned time point. The statistical significance of WT and CNA24 injected mice group was calculated in comparison to saline. For 1°CNA24-2°WT, a comparison was made with 1°Saline-2°Saline using two-way ANOVA (Dunett’s multiple comparisons test). C Expression of Dectin 1 (i), TLR2 (ii), and TLR4 (iii) in renal tissue of pre-immunized mice groups WT (pink), CNA24 (blue), Saline (cyan) were analyzed by RT-PCR. Expression of the genes were normalized with HPRT1 and 2−ΔΔCT values were determined to calculate fold change. The mean ± SEM of 8 mice was shown in the multicolored interleaved bar graph using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (**p ≤ 0.01 and ***p ≤ 0.001).

Since we observed a differential fungal load of various C. albicans strains in the infected organs, they might have been recognized and cleared by the immune cells differently. In addition, the composition of the cell wall of fungi, which is the first recognition site by the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of myeloid cells like macrophages and dendritic cells, also varies in these strains. TLR2, TLR4, and Dectin-2 recognize mannan, whereas Dectin-1 binds β-glucans of the cell wall22. We estimated the expression of PRRs of infiltrated innate cells in infected kidneys to associate their involvement in fungal recognition, immune activation, and clearance (Fig. 4C). Renal cells also express some of these receptors, like TLR2. Transcription analyses revealed that the expression of these receptors (Dectin1, TLR2, and TLR4) increased in fungal-infected organs only. While the level of Dectin-1 remained steady from 3 h to 7 days, the levels of TLRs gradually subsided at later time points following an initial spike within 3 h post-infection due to the WT strain. It suggested that although immune recognition and possibly downstream activation of signaling take place very early in WT-challenged mice, later on, they get suppressed. Contrarily, the expression of these receptors showed a delayed increase in the CNA24-infected group, and they were very high at later time points (7 d and 15 d). A basal level of expression of these PRRs was observed in 30 days, associated with a complete clearance of fungal cells from the vital organs and survival.

Altered immune cell profiling in mice due to the differential virulence of C. albicans strains

The dynamics of tissue-resident immune cells in infected organs determine the strength of pathogen-immune system interaction, the specific immune cells in immunity, and disease progression. Therefore, to determine the immune cell’s kinetics, white blood cells (WBC) from splenocytes of the various mouse groups, as depicted in Fig. 4A, were isolated and profiled by immune-phenotyping using specific fluorescent-tagged antibodies and flow cytometry (Fig. 5A). The Spleen was selected for immune-phenotyping as it is a critical immune organ, as well as it gets infected during fungal infections. An increase in most of the immune cells in CNA24-challenged groups started within 3 h of infection and persisted up to 7 days, but they came down nearly to the basal level on the 30th day (blue and maroon lines). However, in the WT primary challenged mice, a clear decline of most of these cells was observed from 3 h to 7 days, suggesting an onset of immune suppression associated with increased fungal load and disease severity, leading to death within 10 days of infection (pink line). Cells like macrophages + DCs, neutrophils (CD11b+/Gr-1+/hi/SSC(hi)), NK, and B cells (CD11b-/CD19+/CD5+/-) levels spiked to a maximum at 7 days of CNA24 challenged, whereas T cells (CD11b-/CD19-/CD5+), CD43+ NK cells, and CD5+ B cells population showed an early trend increase (3 h to 3 days). In addition, a higher population of CD5+ B cells was also noticed at 30 days of CNA24-challenged mice. Altogether, these results suggested that WT C. albicans induces immune suppression by lowering most of the immune cell count, whereas an early and longer activation of certain innate and adaptive immune cells, followed by their reduction to a basal level in CNA24-infected mice, is most likely involved in fungal clearance and protective immunity.

A The multicolored line graphs show the kinetic alteration of splenic-resident macrophage + DCs (i), neutrophils (ii), B cells (iii), T cells (iv), CD5 + B cells (v), NK cells (vi), and CD43 + NK cells (vii) population in various mice groups (WT-Pink, CNA24-blue, Saline-cyan,1°Saline-2°Saline-purple and 1°CNA24-2°WT-maroon) at various time points after staining the splenocytes with specific antibodies and acquisition of data using flow cytometry. B The multicolored line graphs depict the kinetic alteration of splenic-resident CD4+ T cells (i), CD8+ T cells (ii), TNFα+ CD4+ T cells (iii), IL-17+ CD4+ T cells (iv), IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells (v) population in various mice groups at mentioned time points. The lines join the mean ± SEM (n = 8) for each group and each time point. Statistical significance of WT and CNA24 injected groups were calculated in comparison to saline and 1°CNA24-2°WT was compared with 1°Saline-2°Saline. Data were representative of two separate experiments and analyzed using the two-way ANOVA test (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) using Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software. Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001).

Next, to determine the subset of the T cell population involved in fungal immunity, T cells were sorted and analyzed using specific antibodies (Fig. 5B). A consistently increased population of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was observed in fungal-challenged mice from 3 h to 7 days. It suggested a possible role of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in fungal clearance. Among the CD4+ T cells, IL17 and IFNγ positive populations remained high in CNA24-infected mice, whereas TNFα+ CD4+ T cells were more in CNA24 vaccinated WT re-challenged mice (1°CNA24-2°WT, maroon line). In the WT-infected group, after an initial increase in CD4 + T cell subtypes, they gradually decreased at the 7th day. This data suggested that IFNγ, TNFα, and IL17 producing T cells are likely to be involved in preventing fungal infection in CNA24 immunized mice.

Differential induction of systemic cytokines upon fungal infections

Immune cells in response to a pathogen interaction produce various cytokines and chemokines. Proinflammatory cytokines are primarily involved in initiating a counteractive defense against pathogens; however, overproduction of these is deleterious as they lead to shock, multiple organ failure, and death. Anti-inflammatory cytokines downregulate the exacerbated inflammatory process to maintain cell homeostasis22. An excessive release of anti-inflammatory mediators often results in the suppression of immune function. Chemokines are the chemotactic factors critical for the effective recruitment of leukocytes to the site of infection23. Since we observed differential induction of immune cells in the spleen of various mouse groups, we estimated a panel of serum cytokine and chemokines using a Bio-plex analyzer (Fig. 6). We observed an induction of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in fungal-infected mice irrespective of their virulence status. Maximum cytokine levels were estimated at 7 days post-infection, which reduced gradually in CNA24-challenged groups, albeit with a slower kinetic decline in WT re-challenged mice (1°CNA24-2°WT). A substantial elevation of these cytokines and chemokines was observed even after 15 days of WT reinfection in vaccinated mice. The kinetics of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-5, IL-6, IL-17, INFγ, and TNFα followed a typical protective immune response to fungal burden in CNA24 challenged mice. A very high level of IL-1α, IL-2, and TNFα in WT C. albicans infected mice might have led to high inflammation and shock leading to death in 7 days (Fig. 6A). The kinetic profiles of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-3, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12, and IL-13 also followed a similar pattern as in the case of pro-inflammatory cytokines, except IL-4 (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, IL-4 was elevated only in re-infected vaccinated mice group, whereas IL-9 level remains high in CNA24 primary challenged mice even at 30 days. IL-9, a pleiotropic cytokine, is known to promote both inflammation and tolerance during C. albicans infection24. A very high level of IL-3 and IL-10 at 7 days post-challenge with WT suggested a high degree of immune suppression. Basically, immunosuppression and high inflammation on the 7th day led to a proliferation of fungal infection and death in WT-infected mice. However, a balanced level of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the CNA24-challenged group caused efficient fungal clearance and survival. The concentrations of chemokines such as MCP-1, MIP-1 (α and β), KC, and RANTES were also elevated in the serum of CNA24-infected mice from 3 h to 7 days post-infection periods, and gradually they reduced (Fig. 6C). In the WT-infected group, the chemokine levels were high at 3 days and then started reducing, indicative of immune suppression. Altogether, our data suggested that while a critical balance of the pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines is maintained for a longer duration in mice, which is associated with a gradual decline of fungal burden in the CNA24-challenged group as opposed to high inflammation and immune suppression in WT C. albicans infected mice due to a very high level of these messenger molecules causing fugal proliferation and disease severity.

A The multicolored line graphs show the kinetic alteration of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-17, IFNγ, and TNFα levels in picogram/mL in the serum of various mice groups (WT-Pink, CNA24-blue, saline-cyan, 1°saline-2°saline-purple and 1°CNA24-2°WT-maroon) at defined time points (3 h, 3 d, 7 d, 15 d and 30 d). B The multicolored line graphs depicting the kinetic alteration of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-3, IL-4, IL-9, IL-12(p40), IL-10, IL-12(p70) and IL-13 levels in picogram/mL in the serum of various mice groups at different time points were plotted. C Chemokines like KC, MCP-1, MIP-1β, RANTES, and MIP-1α levels in picogram/mL in the serum of the mentioned mice groups were determined at different time points and represented in multicolor line graphs. The lines join the mean ± SEM of eight mice data for each group and each time point. Data are representative of two separate experiments and were analyzed using the two-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test using Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software. Asterisks indicate the statistically significant differences (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001).

Cell-mediated and trained immunities are pivotal in preventing reinfection

To demonstrate the roles of B cells, T cells, and innate immune cells, along with their receptors and cytokines in protective immunity induced by CNA24, selective cellular depletion and molecular blockade experiments were conducted by administering specific monoclonal antibody to mice (n = 6) after 15 days of post-immunization and the response to virulent re-challenge was monitored (Fig. 7). A schematic diagram to depict depletion strategy has been shown (Fig. 7A). Flow cytometry confirmed significant depletion (>50% of each marker) of these cells and blocking of molecules in splenocytes and blood (Supp. Fig. 3). Anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 for T cells and anti-CD19 for B cells along with respective isotype control antibodies were injected into the CNA24-immunized mice and susceptibility to lethal C. albicans challenge was monitored (Fig. 7B). Upon cellular ablation, 70-100% mice succumbed to infections within 15 days whereas the control antibodies administered mice were mostly resistant to a lethal dose of WT C. albicans (p = 0.0005-0.02). It suggested that B- and T-cells dependent adaptive immunity plays a critical role in immunological memory response, and their depletion is detrimental to re-infection. The expression levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, as well as CD4+ T cells expressing such cytokines, were also very high in vaccinated mice. To find out the significance of these cytokines in antifungal resistance, IFNγ, TNFα, and IL17 were blocked by specific monoclonal antibodies in CNA24-immunized mice, and survivability was monitored upon WT re-challenged (Fig. 7C). All the mice with reduced level of TNFα and IL17 succumbed to re-infection (p = 0.0007–0.0012), whereas about 70% mice dead by IFNγ depletion (p = 0.019) and no mice were affected due to isotype antibodies administration during the 15 days study period. However, the median death time was about the same 6-8 days for the cytokines-depleted mice.

A An illustrative depiction of in vivo cellular and molecular blocking assay of immune cells and markers by specific monoclonal antibodies or a drug. BALB/c mice (n = 6/group) were immunized with CNA24 on 0th day. For respective target depletion on the 15th day, mice were intraperitoneally (IP) injected with the required antibodies/drug or respective isotypes/PBS control. Mice were then rechallenged with a lethal dose of WT on the 17th day. After 2 h of rechallenge, 2nd round of depletion was carried out. Three more such depletions were performed on day 19th, 21st, and 23rd. Survival was monitored for all mice up to the 30th day. The image was generated using BioRender. B A Kaplan–Meier survival curve depicting survival rates of mice depleted for lymphoid cells. CD4-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-CD4)-2°WT), CD8-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-CD8)-2°WT), CD19-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-CD19)-2°WT) groups of mice (n = 6/group) with their respective isotype control 1°CNA24-(IgG2b)-2°WT, 1°CNA24-(IgG2a-AF488)-2°WT, 1°CNA24-(IgG2a-PCCy5.5)-2°WT were monitored for survival. C A Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing survival rates of mice depleted for cytokines secreting CD4 + T cell subsets. IFNγ-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anit-IFNγ)-2°WT), IL-17-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-IL-17)-2°WT), and TNFα-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-TNFα)-2°WT) group of mice (n = 6/group) with their respective isotype control 1°CNA24-(IgG1-AF488)-2°WT, 1°CNA24-(IgG2a-PCCy5.5)-2°WT and 1°CNA24-(IgG1-AF700)-2°WT were monitored for survival. D A Kaplan–Meier survival curve of mice depleted for innate immune cells and PRRs. Macrophage-depleted (1°CNA24-(Clodronate)-2°WT), neutrophils-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-Gr-1)-2°WT), Dectin-1 depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-Dectin-1)-2°WT) and TLR2-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-TLR2)-2°WT), and TLR4-depleted (1°CNA24-(Anti-TLR4)-2°WT) groups of mice (n = 6/group) with their respective PBS and isotype control 1°CNA24-(PBS)-2°WT, 1°CNA24-(IgG2b-AF700)-2°WT, 1°CNA24-(PBS)-2°WT, 1°CNA24-(IgG2a-AF488)-2°WT and 1°CNA24-(IgG2a-FITC)-2°WT were monitored for survival. (E) A Kaplan–Meier survival curve of CPM-induced immunocompromised mice to fungal strains. CPM-treated mice (n = 6/group) were injected intravenously with WT and CNA24 (1 × 104 CFU/mouse) and saline. Survivability was monitored for 30 days. The workflow image was generated using BioRender. Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test using Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software. The P values are mentioned beside the corresponding comparison groups.

Trained innate cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, were shown to recall infection and be involved in memory immune response12,22. Anti-Gr1 antibody and clodronate were injected to deplete the cellular level of neutrophils and macrophages, respectively (Fig. 7D). While the neutrophil and macrophage depleted CNA24-immunized mice (yellowish green and dark blue lines) succumbed to WT re-infection (p = 0.0005–0.0008), isotype controlled immunized mice were protected (pink and black lines). Dectin-1, encoded by the CLEC7A gene, is widely expressed in neutrophils, monocytes, and DCs. Its interaction with β-glucan is known to induce metabolic and epigenetic changes in neutrophils to enhance memory response. TLR2 and TLR4, which recognize mannan-containing structures of the C. albicans cell wall, are expressed in monocytes and macrophages, DCs, polymorphonuclear cells, endothelial, epithelial cells, etc25. Similar to Dectin-1, reports also suggest the involvement of TLR2 and TLR4 in trained immunity26,27. To strengthen the role of innate immune cells in long-term memory response, we neutralized these PRRs by specific monoclonal antibodies to the CNA24-vaccinated mice, re-infected with WT C. albicans, and survivability was monitored (Fig. 7D). While 100% of the immunized mice blocked with anti-Dectin-1 antibody succumbed to re-infection (p = 0.0005), 70% mice did not get protected from re-infection due to TLR2 and TLR4 blocking. In this experiment also the isotype antibody-mediated control did not alter the survival of immunized mice significantly to lethal re-challenge. Fungal sepsis in the killed mice was confirmed by PAS staining and CFU score (Supp. Figures 4 and 5). This result suggested that neutrophils and macrophages, and their PRRs like Dectin-1, TLR2, and TLR4, are critical in long-term memory immune response in the CNA24-vaccinated mice, which confirmed the involvement of trained immunity in preventing re-infections. Altogether, the molecular blocking and cellular neutralization of B- and T-cells, and innate immune cells, suggested that innate immunity functions both in early and late immune responses, while B and T cells mediated adaptive immunity functions to substantiate memory response against fungal infection.

Candidiasis is usually a disease of immunocompromised ailment. Our earlier study suggested that CNA25 was safe but did not develop protective immunity to fungal reinfection in SCID mice. To check the safety of CNA24 strain, the mice with reduced immunity were generated by cyclophosphamide (CPM) treatment, after 3 days they were challenged with WT and CNA24 strains, and survivability was monitored (Fig. 7E). Since 5 × 105 WT cells per mouse inoculum size was very toxic to these mice, the inoculum size was were reduced to 1 × 104 cells per mouse. As CPM induces neutropenia, a reduced level of neutrophil population was seen in spleens than the untreated samples (Supp. Figure 3D). The survival analysis suggested that while all such immunosuppressed mice succumbed to WT infection, similar to saline control, the CNA24-administered mice were healthy and survived. PAS-stained kidney sections and fungal burden by CFU analyses further ascertained the fungal sepsis in succumbed mice (Supp. Figures 4D and 5D). Thus, this data suggested that CNA24 could be avirulent and safe for immunization even in immunocompromised conditions.

Discussion

Systemic candidiasis or candidemia poses a serious threat to human health globally due to the lack of early diagnostics, effective chemotherapeutics, and vaccines. Although all the approaches that were used for developing successful vaccines against viruses and bacteria have been attempted for fungal pathogens, antifungal vaccines remain an unmet medical need2. The live whole-cell vaccine strategy against viruses and bacterial pathogens is widely employed28. Such vaccines are nothing but the whole pathogens that were fully attenuated of virulence by genetic ablation. They are multi-antigenic and highly immunogenic to boost memory immune responses without costing much to the host’s health, but prevent re-infection. Essential processes like DNA replication, transcription, and protein translational machinery are the usual targets to design and develop drugs and vaccines against pathogens. In a quest to design an antifungal vaccine, we have generated a repertoire of DNA polymerase knockout strains of C. albicans that are being explored. In our earlier reports, we found that targeting different DNA polymerases involved in the synthesis of different strands led to distinct protective efficacies. The defective Polε strains due to the loss of Dpb3 and/or Dpb4 subunits are avirulent; however, upon vaccination, they do not protect against C. albicans re-challenge10. Contrarily, CNA25, where the Pol32 subunit of Polδ was deleted, protects against pan-fungal re-infection effectively12. This discrepancy in vaccine efficacy of these two strains is mostly due to their differential growth sensitivity at the ambient temperature of the host, as while CNA25 grows normally, the dpb3ΔΔdpb4ΔΔ strain exhibits temperature sensitivity at 37 °C. These studies thus suggested that the transient replication of the attenuated strain in the host seems to be critical to elicit robust protective immune responses, and the live attenuated strain is a better option to develop an effective vaccine than the non-replicative strain. At the same time, the deletion of a TLS DNA polymerase Polη has a detrimental effect as the null strain (CNA7/rad30ΔΔ) enhances the virulence attributes of C. albicans8. Here, we characterized two dual-DNA polymerase knockout strains (rad30ΔΔpol32ΔΔ and pol32ΔΔrad30ΔΔ) with vaccine potential to determine the possible impacts of two polymerases on each other’s contributions to genome stability, cell wall remodeling, macrophage evasion, pathogenesis, immunogenicity, and protective immunity.

Since Pol32 is a dispensable component of replicative DNA polymerase Polδ, and Polη is involved in TLS, as expected, the double-deletion of both genes did not affect the survivability and growth of C. albicans at normal physiological conditions. However, as both Polδ and Polη are critical enzymes required for DNA damage response, upon DNA damage induction, the strains exhibited retarded growth, more severe than even individual null strains. The reversible morphological transition from blastopore to pseudo-hyphal to hyphal forms is a critical determinant of virulence29. Deletion of the RAD30 or POL32 gene reduced germ tube length induced by serum at 37 °C and showed altered cell wall structure and composition8,9. The cell wall thickness and β-glucan enrichment in these strains were very similar to CNA25. As shown earlier, CNA7 possessed a thicker innermost chitin layer than other strains used in this study8. Whether the replication stress due to the deletion of various DNA polymerases induces different signaling cascades to alter cell wall structure and composition requires further investigation. Irrespective of the order of deletions, both rad30ΔΔpol32ΔΔ (CNA24) and pol32ΔΔrad30ΔΔ (CNA298) strains showed similar stress-induced growth and filamentation defects, and these phenotypes seem to be governed by Pol32’s function, as CNA25 also showed similar characteristics. Therefore, it was intriguing to determine and compare the virulence, immunogenicity, and vaccine competence of these strains in cellular and pre-clinical models. The macrophage - C. albicans co-culture experiment revealed that CNA24 is relatively less virulent and cannot evade the immune system as efficiently as CNA7 and WT. As opposed to CNA7, which is a hyper-virulent strain, using the systemic candidiasis mice model, further we confirmed that both CNA24 and CNA298 strains are attenuated due to the deletion of POL32, as all the mice administered systemically with these strains survived and did not show any symptoms of morbidity. The fungal burdens in vital organs were significantly reduced to a negligible level from 3 h to 15 days post-infection, leading to survival of CNA24 primary challenged mice. Since we observed CNA24 cells in the essential organs of mice, although in very low counts, it suggested that CNA24 replicates transiently in the host and eventually immune cells clear it, unlike the WT C. albicans strain. Like CNA25, CNA24 is also highly immunogenic as its administration caused immune activation and a balanced induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (Figs. 4–6, blue lines). More importantly, the deletion of RAD30 in pol32ΔΔ genetic background did not revert the strain to the virulent phenotype. Thus, this study further strengthened that POL32 is critical for the normal progression of systemic infection by C. albicans in animals and is a true virulence factor, and its deletion in any genetic background could lead to the attenuation of virulence.

Then, do CNA24 and CNA298 represent true replicates of CNA25? To compare the vaccine potential of these strains, survival rates upon re-infection, fungal burdens, organ pathology, immune cell profiling, cytokine production, and protective immunity were assessed. The survival rate of CNA24 and CNA298-vaccinated mice upon pathogenic re-challenge varied from 50-60%, while the survival time of all the mice was significantly longer as opposed to sham-immunized mice. However, as reported earlier also all the mice vaccinated with CNA25 were protected from pathogenic WT C. albicans re-challenge. In this study as well, we observed that vaccine efficacy is better through intravenous route of immunization. Since the protective efficacy in CNA25 was better than CNA24 and CNA298, it implies that the resistance to re-infection was compromised due to the loss of Polη. Detailed transcriptomics and proteomics analyses may reveal the exact reason for the differential efficacy of protection. Nevertheless, the surviving re-challenged mice due to CNA24 immunization showed a gradual lessening of fungal burden, a balanced level of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, and activation of innate immune, B, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells quite similar to those in CNA25 vaccinated mice. Cell-mediated adaptive immune responses involving CD4+ T helper cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells are critical for mitigating Candida infection. While CD4+ T-cell immune responses that include Th1 and Th17 are protective against Candida infection, CD8+ T-cells because of their cytotoxic activity and cytokine secretion ability to arbitrate resistance to systemic fungal infections30,31. While the T cell involvement in protective immunity is well established, the role of B cells remains paradoxical5,32,33. While some studies suggested that B-cell deficiency did not alter the susceptibility of the animals to candidiasis, few others reported the contrary results32,33,34,35,36. Recently, we found that the SCID mice are susceptible to systemic candidiasis and even after immunization with CNA25, did not develop immunity to reinfections12. In this study, we demonstrated the importance of B and T cells in memory responses by depleting these cells with anti-CD19, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8 antibodies in CNA24-vaccinated mice. Although B cells may be involved in cell-mediated immunity by secreting cytokines, humoral immune responses driven by B cells may not be critical. A report suggested that the IgA levels are found to be the same in healthy controls and patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis37. Cytokines and chemokines produced by immune cells serve as the key mediators of host-pathogen interaction. A gradual induction of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL3, IL10, and IL13 in the WT-challenged group led to immunosuppression that is associated with increased fungal burden and death of mice within 10 days of post-infections. Whereas higher expression of cytokines like IL1, IL17, TNFα, etc will cause hyperinflammation and tissue damage. Thus, the combination of hyper-inflammation, immunosuppression, and proliferation of fungal cells caused death in mice with WT primary infection. However, bell-shaped immune responses led to fungal clearance and survival in the CNA24-immunized re-infected mice group. Also, the molecular blockade in immunized mice suggested that IL17, IFNγ, and TNFα play critical roles in protective immunity by CNA24.

Upon primary challenge with CNA24 and CNA298, these cells are encountered by the first line of defense immune cells like neutrophils and macrophages. The pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) on the cell wall of fungal cells get recognized by the PRRs expressed on the innate cells and as these strains are avirulent, they get cleared. Further, the cell-mediated adaptive immunity gets activated to prevent reinfections in CNA24 and CNA298 vaccinated mice. In addition to innate and adaptive immunity, recent trends suggest that trained immunity is also involved in long-term memory response against fungal pathogens. Trained immunity is induced through the interaction of the β‑glucans of C. albicans with Dectin-1 of innate immune cells followed by activation of the non-canonical RAF1-cAMP signaling pathway causing epigenetic imprinting through histone methylation and acetylation, and metabolic reprogramming, thereby, it boosts pro-inflammatory cytokines production in trained monocytes and macrophages. Similar to Dectin-1, reports also suggest the involvement of TLR2 and TLR4 receptors in trained immunity26,27. Molecular blockade of Dectin-1, TLR2, and TLR4 caused the CNA24-vaccinated mice to be susceptible to C. albicans pathogenic challenge, while the no-depleted mice showed resistance to re-challenge.

In conclusion, this study identified two dual DNA polymerase defective strains as attenuated strains for live whole-cell vaccine development. More importantly, it suggested that irrespective of genetic backgrounds, deletion of POL32 in C. albicans and probably in other non-albicans species as well could lead to attenuation of virulence and such strain can induce cell-mediated adaptive and trained immunity to prevent reinfections. Depletion or neutralization of any cells (CD4+, CD8+, CD19+, neutrophil, and macrophages) or molecules (IL17, IFNγ, TNFα, Dectin-1, TLR2, and TLR4) showed reduced memory responses and increased susceptibility drastically to reinfections suggesting that a concerted action of both adaptive and trained immunity responses is critical for long-term memory. As these strains are multi-antigenic, adjuvants may not be needed to improve immunogenicity and vaccine efficacy. Since similar to CNA25, these strains prevent re-infection effectively via intravenous route, a suitable and safer mode of immunization is yet to be figured out. However, recent several reports of vaccines against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and malaria in mice, primates, and human suggested that intravenous immunization is also safe and more effective than the other routes38,39,40. Nevertheless, as CNA25, CNA24, and CNA298 strains protect the mice from fungal re-challenge via IV route without evident safety concerns, these candidate strains have enormous translation potentials to fully develop as vaccines.

Methods

Mice, Cell lines, fungal strains, reagents, and oligonucleotides

In-house breed BALB/c male mice of 6 to 8 weeks were housed in individually tagged well-ventilated cages at a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C, relative humidity of 55 ± 10%, and a light/dark cycle of 12 h/12 h, with free access to food and water. The RAW 264.7 (murine macrophages) cell line was procured from the stock center of NCCS, Pune, India. The wild type strain C. albicans SC5314 and various derived knockouts are enlisted in Supplementary Table 1. The strains were grown in YPD media and if required 2% of maltose was added to Yeast extract + Peptone liquid media for curing of the NAT-cassette during knockout generations. YPD media (Cat# 4001032), Maltose (Cat#102241), Hydroxyurea (Cat#102023), Cisplatin (Cat#198872), and MMS (Cat#205518) were procured from MP Biomedicals, USA. Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) Stain Kit (Cat# ab150680) was obtained from Abcam, Cambridge, USA. The LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit (Cat# 2089943) was brought from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, MA, USA, and the Zombie Yellow™ Fixable Viability Kit (Cat# 423103) was purchased from BioLegend. While the RPMI 1640 media (Cat# 11875093) was provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific, the Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Salt Solution without Ca and Mg (Cat# P04-36500) and Fetal Bovine Serum-South American Origin (Cat# P30-3302) were bought from PAN Biotech. The Ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) (Cat# 60114505001730), Na2EDTA (Cat# 1.93312.1021), Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) (Cat# S6014-5009), Aniline Blue solution (Cat# B8563), cyclophosphamide monohydrate (Cat# C0768), and Fluorescent Brightener Calcofluor White (Cat# F3543) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Concanavalin A (Con A) tetramethylrhodamine (Cat# C860) was purchased from Invitrogen. The oligonucleotides used in this study were procured from Integrated DNA Technologies and Eurofins. The antibodies and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3, respectively.

Generation of knockout C. albicans strains

To generate knockout of the POL32 gene in CNA7 (rad30ΔΔ) and RAD30 gene in CNA25 (pol32ΔΔ), a modified SAT1 flipper strategy was used15. The deletion constructs share a common downstream sequence of the desired gene while they differ by lengths of upstream sequences. The already available deletion cassette pair pNA1554, pNA1559, and pNA1389, pNA1451 were used to delete POL32 and RAD30 genes, respectively. Two rounds of transformations of these cassettes and curing of NAT led to the generation of homozygous deletion strains CNA24 (rad30ΔΔpol32ΔΔ) and CNA298 (pol32ΔΔrad30ΔΔ).

Growth curve

Various C. albicans strains (WT, rad30ΔΔ, pol32ΔΔ, rad30ΔΔpol32ΔΔ, and pol32ΔΔrad30ΔΔ) were grown overnight in YPD broth. The pre-cultures were diluted to an OD600 = 0.01 with fresh 10 mL YPD media and allowed to grow at 30 °C and 200 rpm. Absorbance was measured at OD600 nm up to 14 h with an interval of 2 h. The OD values were plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0. The experiment was performed twice with technical triplicates.

Genotoxic agents and temperature sensitivity

Spot dilution-based sensitivity assay was carried out as described before41. Briefly, for evaluating temperature sensitivity, the cultures of various strains were serially diluted and spotted on YPD agar plates followed by incubation at 16 °C, 30 °C, 37 °C, and 42 °C for 24–48 h. To check the effect of genotoxic reagents, the serially diluted cultures were spotted without or with varied concentrations of HU (10 mM, 20 mM, and 30 mM), MMS (0.004%, 0.006%, and 0.008%), TBHP (0.016%, 0.024%, and 0.032%) and Cisplatin (0.5 mM, 0.75 mM, and 1.0 mM). For UV sensitivity, the plates were exposed to different doses of UV (16 j/m2, 32 j/m2, and 48 j/m2) and wrapped with aluminum foil. Spotted plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. Images of the plates were captured in the ChemiDoc imaging system.

Morphology of C. albicans

For colony morphology, about 200 µL of diluted pre-cultures of WT and CNA24 were spread on YPD-FBS agar media (1% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 4% dextrose, and 10% FBS) and complete FBS agar media (10% FBS). Plates were incubated at 37 °C, and images were taken after the mentioned duration of incubation. For germ tube development, an equal number of C. albicans cells of WT, CNA7, CNA25, CNA24, and CNA298 were cultured in a YPD medium containing 10% FBS at 37 °C and 200 rpm for 1 h and observed under the microscope. Images were captured and lengths of germ tubes (n = 100) for each strain were measured using Image J software and represented in a graph using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The ultrastructure of WT, CNA7, and CNA24 cells was visualized by TEM using a procedure described before11. Briefly, cells were harvested and washed with 1 mL of 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. Fixation was done with 1 mL of glutaraldehyde (2.5%) for 1 h at room temperature. The fixed cells were subsequently washed using cacodylate buffer followed by post-fixation using 200 μL of 2% osmium tetroxide for 2 h. The dehydration process was carried out with an increasing concentration of alcohol and 10 min of each incubation. Next, the pellet was incubated with propylene oxide (500 μL/treatment) for 10 min twice and then resuspended in a 1 mL mixture of propylene oxide and Spurr’s resin (1:1 ratio) for 3 h. To infiltrate the samples, they were kept in pure resin at room temperature overnight, followed by centrifugation, and the resin was discarded. To carry out embedment, the pellet was resuspended in resin mixed with hardening reagent DMAE (Ted Pella, Inc.). The mixture was incubated at 60 °C for 48 h leading to polymerization. The hardened sample was sectioned carefully using Leica EM UC7 microtome to obtain ultrathin sections of 70 nm. The sections were collected on the copper grid with the help of a loop, then dried and stained with uranyl acetate for 30 min, followed by 3 washings with distilled water, and allowed to dry for 2 h. Samples on the grid were visualized under the JEM-2100Plus JEOL TEM imaging machine with various magnifications. Cell wall thickness values for each strain were represented in a graph using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

Estimation of cell wall content by flow cytometry

The cell wall content of C. albicans WT, CNA7, and CNA24 was measured using a methodology described previously with a minor modification11. The overnight-grown cultures of WT, CNA7, and CNA24 were diluted to OD600 to 0.5. Cells from 1 mL of the diluted cultures were harvested, washed thrice, and resuspended in 1 mL PBS. CFW (2.5 µg/mL), aniline blue (2.5%), and ConA tetramethyl rhodamine (1 mg/mL) were used to estimate the chitin, β 1,3-glucan, and mannan content, respectively. Staining was done for 30 min at 30 °C in the dark. After staining, cells were washed with PBS to remove the extra stain, resuspended in 500 µL PBS, and transferred to FACS tubes for flow cytometry in BD LSR FortessaTM cell analyzer. UV laser was used for CFW and aniline blue, with an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and a bandpass filter (450/50 nm), while yellow-green laser was used for Con A that had an excitation wavelength of 561 nm with a bandpass filter (586/15 nm). The experiment was performed out in triplicates and an average of mean florescence intensity was calculated. The mean fluorescence intensity obtained was analyzed and processed in the FlowJo software, which was represented as a graph using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

Phagocytosis, fungal clearance, and macrophage killing assay

C. albicans and macrophage interaction was assessed via the following assays42. About 50% confluent RAW 264.7 murine macrophage were counted and approximately 5 × 105 cells were seeded in each well of 12-well plates with complete DMEM and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator. After 24 h of incubation, seeded RAW 264.7 cells were washed with DMEM, stained with cell tracker deep red dye (1 µM), and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min, followed by washing with DMEM. Likewise, freshly streaked isolated colonies of WT and CAN24 C. albicans strains were inoculated in 5 ml YPD and cultured at 30 °C, 200 rpm for 24 h. The C. albicans cells were properly washed with PBS and counted, and about 5 × 105 cells were stained with CFSE dye (20 nM). The stained fungal cells were added to each well containing stained RAW 264.7 cells in a ratio of 1:1 and co-cultured for 3 h (3 time points with an interval of 1 h). After each hour, the supernatant was discarded from the well to get rid of non-phagocytosed fungal cells, whereas the adhered cells were scraped and collected in the FACS tube. The FACS tubes containing stained cells were centrifuged at 380 g for 5 min at 4 °C in an upright rotor, supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in FACS buffer (0.1% BSA + PBS) for acquisition in a flow cytometer. Cells were acquired in BD LSR Fortessa and populations were sorted by the FITC channel (CFSE) and APC channel (deep red). After the acquisition, data was exported as FCS files and analyzed using FlowJo Software. The phagocytosis efficiency was calculated by gating the cells and determining the percentage of double-positive cells (FITC + APC + ). To perform a fungal clearance assay, a similar kind of experiment was carried out by taking RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells (unstained) and C. albicans cells (unstained). After each time interval, co-cultures were gently washed to remove the non-adhered cells and 1 mL of warm water (50–60 °C) was added into each well for release of phagocytosed C. albicans form macrophages. The cells from the wells were collected via scraping and diluted to a desired dilution for spreading in YPD agar plates. After incubation of plates at 30 °C for 2 days, colonies were counted and represented in a bar graph using GraphPad Prism 8.0. For macrophage killing assay, propidium iodide was used to stain a mixture of RAW 264.7 cells and C. albicans strains (1:1), and covered in aluminum foil followed by incubation at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator for 2.5 h. After the incubation, images were captured using EVOS imaging system to analyze lysed macrophages. Dead macrophage cells were plotted in a bar graph using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Systemic candidiasis development in mice model

Male BALB/c mice of 6 to 8 weeks (n = 6–8 in each group) were acclimatized, and WT, CNA24, CNA25, and CNA298 strains were administered intravenously along with the saline control. For preparation of inoculum, the overnight grown C. albicans strains were washed thoroughly with sterile distilled water to remove residual YPD media, followed by washing with Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (dPBS) and finally resuspended in dPBS. The cells were counted using the Neubauer chamber slide in the central area (5 × 5 small squares) and 5 × 106 cells/mL cell suspension in dPBS was prepared. Mice groups were injected via lateral tail vein with a dose of 5 × 105 CFU per mouse (100 µL from a stock of 5 × 106). To check the efficacy of vaccination, mice were vaccinated with one dose of 5 × 105 cells of CNA24, CNA25, and CNA298 per mouse. Sham immunization was done with saline control. Post 30 days of immunization, the surviving mice were rechallenged with 5 × 105 CFU of WT C. albicans intravenously. To determine the vaccine efficacy through alternate route of immunization, groups of BALB/c mice (n = 8/group) were infected with the same CFU of CNA24 via subcutaneous administration along with the saline control, and after 15 days one of the groups was again immunized with a booster dose of CNA24. After 30 days, a secondary lethal challenge via lateral tail vein with WT C. albicans was carried out and survival was monitored. All the mice were monitored for the next 30 days. Mice were observed daily to check for any kind of moribund state. This time point was noted and taken into consideration as the death of that particular mouse. Mice were euthanatized, dissected, and vital organs (spleen, liver, and kidney) were collected for further analyses. Mice were first anesthetized via isoflurane inhalation (2%) and euthanized by cervical dislocation. The survival curve was plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software for each group of mice. In some experiments, mice were allowed to survive for 6 months and then handed over to animal care for necessary disposal.

CFU assay

To calculate the fungal burden in various organs such as the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidney; organs were homogenized separately with a tissue homogenizer. After homogenization, serial dilutions of homogenates were made with 1x PBS up to 10-3 and spread on YPD+ chloramphenicol (34 μg/mL) plates to get an accurate count of fungal cells. Plates were kept at 30 °C for 48 h. Colonies were counted, back-calculated based on the dilution factor, and represented in graphs using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Kidney PAS staining

Formalin fixed paraffin embedded kidney samples were sectioned in LEICA RM2125 RTS microtome having a thickness of 5 µm and collected on a slide. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene, and gradually rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100%, 95%, and 75%) and distilled water. Kidney sections were oxidized with 0.5% periodic acid solution (PAS) for 5 min and then rinsed with distilled water. After that sections were dipped in Schiff reagent for 15 min followed by washing with lukewarm tap water. Mayer’s hematoxylin was used for counter staining for a minute followed by washing with running tap water. The slides were dehydrated with increasing concentration of ethanol (75%, 95%, and 100%), then mounted with D.P.X. mounting liquid and allowed for drying. Images were captured using a LEICA MD500 microscope with 40X magnification.

Kinetic analyses of immune response in pre and post-immunized mice

To examine fungal burden and immune response of mice towards various infections under different conditions, a kinetic experiment was planned. The complete experiment was segregated into two sets pre-immunization (1°) and post-immunization (1° and 2°) groups. In the pre-immunization set, 3 groups of mice were intravenously injected with saline, WT, and CNA24 C. albicans (5 × 105 CFU/mice). In the second set, a group of BALB/c mice was intravenously immunized with the same dose of CNA24 along with a similar group of sham immunization with saline. After 30 days of immunization, sham immunized mice were again injected with saline while the CNA24 immunized mice were rechallenged with a lethal dose (5 × 105 CFU/mice) of WT. At different time points (3 h, 3 d, 7 d, 15 d, and 30 d), mice (n = 8) from each group were euthanatized and organs like spleen, kidney, lungs, and brain were collected for various analyses. In the WT C. albicans primary challenged group, rarely any mice survived beyond 7 days, therefore, the kinetic analysis was not followed beyond this period. Just before the sacrifice of each mouse, about 300 µL of blood was collected by cardiac puncture and kept without anticoagulant to isolate serum by centrifuging at 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The collected serums were stored at -80°C in individually labeled cryovials until further analysis. Spleens were collected in complete RPMI media for splenic cell isolation and kept in ice. Out of 16 kidneys from each mice group, 8 kidneys were kept in 1x PBS for CFU assay along with lungs and brains, the remaining 8 kidneys were divided into longitudinal halves, one half was kept in 4% Formalin for tissue histology, and the other half was kept at −80 °C with 300 µL TRIzol reagent for RNA isolation.

Gene expression analysis by RT-PCR

Kidneys stored with TRIzol were gently homogenized with the help of a sterile micro-homogenizer and RNA was isolated using the Gene JET RNA purification kit (Cat# K0731, ThermoFisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized by taking approximately 2 µg of RNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Cat# A48571, ThermoFisher Scientific). Diluted cDNA was subjected to quantitative RT-PCR using the required sets of gene primers mentioned in the supplementary Table 3. For 20 μL of the PCR reaction, 10 pmol primers, 10 μl of SYBR Green master mix, and 100 ng of cDNA were used with a reaction condition having initial denaturation (95 °C, 2 min), final denaturation (95 °C, 5 s), annealing and extension (60 °C, 30 s) for 40 cycles were deployed. The PCR was performed using Quant Studio 3 with fast cycle conditions. The expression of genes was normalized with HPRT1. The data obtained were analyzed for fold change in expression using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The graphs were plotted for individual genes using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

Murine splenocytes isolation and Immunophenotyping

The complete procedure of splenocyte isolation was carried out in a cell culture biosafety cabinet as described previously12,43. Briefly, after removing fats with repeated washing with PBS, spleens were put into a cell strainer that was already kept on a sterilized petri dish containing 2 mL PBS + 0.1% BSA and mashed gently using the plunge end of sterilized syringes. Homogenized cells were collected carefully using a pipette from each Petri dish in sterilized 15 mL falcon tubes. Subsequently, 3 mL of PBS + 0.1%BSA was used to properly wash the strainer and petri dish, collected in the same falcon tubes. The mashed cells were pellet down at 380*g for 5 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 2 mL of 1x RBC lysis buffer (NH4Cl, Na2EDTA, and NaHCO3), mixed thoroughly by gentle inversion, and allowed to incubate for 5–10 min in ice. After incubation, the volume was adjusted to 5 ml with the same RBC Lysis buffer and again pelleted down. This lysis of RBC was continued 2–3 times until RBC ghosts, fats, and debris were removed properly. After proper lysis of splenocytes, cells were centrifuged in 1 mL of PBS containing 0.1%BSA, and the cell pellets were properly resuspended in 1 mL PBS + 0.1%BSA. Approximately 10 μL of single-cell suspension was used for cell counting in the hemocytometer by mixing with trypan blue and kept in ice to carry out further experiments.

Immunophenotyping of splenocytes

Splenic cells were transferred to sterilized and properly labeled FACS tubes for antibody staining. About 1.5 million cells were taken for antibody staining. The cells were first proceeded with live-dead staining using the Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit or Zombie Yellow Fixable Viability Kit. One set of staining was carried out with APC-Cy7 anti-mouse CD11b, Alexa flour 700 anti-mouse Gr-1 (Ly6G/Ly6C), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD19, Alexa flour 488 anti-mouse CD5, Brilliant violet 510 anti-mouse CD43, and APC anti-mouse CD161 antibodies to determine the Myeloid (Macrophages +DCs, Neutrophils) and Lymphoid Population (B cells, T cells, CD43 + NK cells and NK cells). Alexa Fluor700 anti-mouse CD44, Alexa Fluor488 anti-mouse CD8a, and PE anti-mouse CD4 to discriminate T cells subpopulations (CD8+ and CD4+ T cells) antibodies were used for 2nd set of cell staining. The unstained control, single-colored control, and antibody-stained samples were incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature for proper staining. Further, cells were cleaned with PBS containing 0.1% BSA. The samples were then acquired using BD LSRFortessa Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) using a proper gating strategy. To prevent spectral overlap, fluorescent compensation was done. FCS files were exported for data analysis by FlowJo 8.0 software. The graph was plotted using the percentage of cells using GraphPad Prism 8.

CD4+ T cells isolation and determination of various subpopulations

About 5 x 107 splenocytes were taken for isolating CD4+ T cells by using Dynabeads™ Untouched™ Mouse CD4 Cells Kit (Cat# 11416D, Invitrogen). PMA (10 ng/mL) and Ionomycin (1 μg/mL) were used to activate CD4+ T cells. After 4 h of incubation in RPMI 1640 complete medium under the standard aseptic cell culture condition CD4+ T cells get activated. 1 µL of brefeldin A (3 ng/mL) was added to stop the reaction during 3rd hour of this incubation. The activated cells were collected, washed, and resuspended in 2% FBS, 2 mM EDTA in PBS pH 7.4. This step was followed by live dead blue staining. Further cells were washed properly and fixed using 150 µL BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution for 30 min. The fixed cells were again resuspended, washed and permeabilized using 400 µL of Perm/Wash Buffer for 20 min followed by staining with fluorescently tagged antibodies such as Alexa flour 700 anti-mouse tumor necrosis factor-alpha, PerCPcy5.5 Interleukin-17A and Alexa flour 488 anti-mouse Interferon-gamma antibodies for the determination of TNFα, IL17, and IFNγ positive population respectively for 45 min at room temperature. After washing twice with PBS + 0.1%BSA, the stained cells were acquired in BD LSRFortessa, and Flowjo 8 Software was used for analysis. Multicolored line graphs were plotted for each immune cell with individual groups at different time points using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

Serum cytokine estimation

A total of 23 (20 of them shown in data) different pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and other chemokines namely IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-3, IL-4, IL-9, IL-12 (p40), IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, KC, MCP-1 (MCAF), MIP-1β, RANTES, MIP-1α were estimated by using the Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine 23-plex Assay kit (Cat# M60009RDPD). The serum samples were first diluted with sample diluent provided in the kit in the ratio of 1:4 and further by using standard diluent which is also provided in the kit, eight standards (S1 to S8) were prepared by 4-fold dilution. By taking a 96-well transparent flat bottom black plate, a mouse cytokine 1x assay bead was added in each well and subjected to washing using 100 µL wash buffer. In the 96-well transparent flat bottom black plate, standards and blank control (Only assay buffer), along with about 50 µL of each sample were added in the respective wells and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min in a plate shaker with 850 + /− 50 rpm followed by washing in 100 µL wash buffer. Further, to each well 25 µL of 1x detection antibody was added and incubated in the dark for 30 min by covering with aluminum foil and again subjected to washing in 100 µL of wash buffer. Finally, 50 µL of 1x SA-PE (streptavidin-phycoerythrin) was added to each well and allowed to incubate in the dark for 20 min. This step was followed by washing and resuspension using 100 µL of assay buffer provided in the kit. The plate was covered with aluminum foil and allowed to mix in a plate shaker with 850 + /− 50 rpm for 1 min at 25 °C and the plate was analyzed in Bio-Plex® 200 System (Bio-Rad). Multicolored line graphs were plotted for each cytokine expressed in picogram/mL with individual groups at different time points using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

In vivo molecular blocking and cellular depletion assay

For selective depletion of specific molecules and cell types, monoclonal antibodies were used which target the desired populations as described before12. For the depletion experiment, BALB/c mice of 6–8 weeks (n = 6/group) were intravenously (IV) administered with CNA24 (5 × 105 CFU) depicted as 1°CNA24 0th day. On the 15th day of post-immunization, the mice were injected with 100 µL of antibodies like anti-mouse TLR2 (1 mg/kg for TLR2 blocking), anti-mouse TLR4 (1 mg/kg for TLR4 blocking), Fc hDectin-1a (25 µg/kg for Dectin-1 blocking), anti-mouse IL17 (0.5 mg/kg for IL-17 blocking), anti-mouse IFNγ (1 mg/kg XMG1.2 for IFNγ blocking), anti-mouse TNFα (1 mg/kg for TNFα blocking), anti-mouse CD19 (1 mg/kg for B lymphocytes depletion), anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5) (10 mg/kg for CD4 + T lymphocytes depletion), anti-mouse CD8 (1 mg/kg for CD8 + T lymphocytes depletion), anti-mouse Gr-1 (1 mg/kg Ly6G/Ly6C for neutrophils depletion), and PBS or respective isotype controls with specific fluorochrome conjugation (rat IgG2b anti-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (10 mg/kg), rat IgG2a (0.5–1 mg/kg), rat IgG1 (1 mg/kg), rat IgG2b (1 mg/ kg) intraperitoneally (IP). For macrophage depletion, 100 µL of clodronate (50 mg/kg) or PBS as respective isotype was administered. PBS was used as a diluent to get the exact concentration of antibodies. After 2 days of post-antibody injection, WT (5 × 105 CFU/mice) and 100 µL saline were given by lateral tail vein injection. After 2 h of WT lethal challenge, 2nd dose of respective antibodies or isotypes were injected intraperitoneally. With an interval of 2 days three more doses of respective antibodies or isotypes were injected. Survivability was observed for the next 15 days. The mice were euthanatized according to the humane endpoint. After sacrificing the mice, blood in K2EDTA and vital organs such as the spleen in RPMI and kidney in PBS and formalin were collected. The kidneys in PBS were proceeded for CFU determination and the kidneys in formalin were used for PAS staining. Spleen and blood cells were processed to confirm the depletion of specific targets via flow cytometry.

Depletion confirmation by flow cytometry