Abstract

This retrospective cohort study evaluated the risk of maternal safety outcomes, including preterm birth, following prefusion F protein (RSVpreF) during pregnancy compared with an unvaccinated cohort using large-scale real-world data. Propensity score matching was performed to compare the risks of preterm delivery, hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP), gestational diabetes (GDM), oligohydramnios, placental abruption, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and intrauterine fetal death (IUFD) to calculate the odds ratio (OR). Following the propensity score matching, 11,265 and 11,265 pregnant women with and without RSVpreF vaccination were included, respectively. After matching, the ORs in the vaccinated group compared with the unvaccinated group were 0.98 [0.84–1.14], p = 0.789; 1.01 [0.96–1.08], p = 0.644; 0.98 [0.90–1.06], p = 0.570; 0.77 [0.63–0.95], p = 0.015; 0.99 [0.77–1.27], p = 0.949; 0.94 [0.86–1.03], p = 0.189; and 0.68 [0.38–1.22], p = 0.189 for pre-term delivery, HDP, GDM, oligohydramnios, placental abruption, IUGR, and IUFD, respectively. Maternal RSV vaccination did not increase the risk of selected maternal outcome events. However, further safety monitoring with larger sample size is required to detect rare events or small risk differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global disease burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is substantial among young children, especially infants younger than 6 months of age1. Recently, maternal RSV vaccination and infantile long-acting monoclonal antibodies (e.g., nirsevimab and clesrovimab) have been developed to prevent severe outcomes associated with RSV infection among infants and are used in high-income countries2,3,4. While the clinical data of nirsevimab have shown its safety and effectiveness, the cost of long-acting antibodies for infants is a concern for its widespread introduction in low- and middle-income countries5,6.

A non-adjuvanted bivalent recombinant RSV prefusion F protein vaccine (RSVpreF) for pregnant women was shown to be effective to protect their infants from severe RSV infection in a clinical trial2 and was approved for use in the US as a maternal vaccination in September 20237. In the phase III trial with approximately 3600 participants in each RSVpreF and placebo arm, the risk ratio of preterm birth (<37 gestational weeks) in the RSVpreF group was 1.20 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.98–1.46), compared with the placebo group. In this trial, 68 (1.8%) and 53 (1.4%) patients in the RSVpreF and placebo groups, respectively, had preeclampsia. Further investigations using large-scale real-world data are needed, given the rarity of these maternal outcomes8.

Real-world evidence regarding the maternal safety outcomes of RSVpreF remains limited. A recent US study from two medical centers with approximately 1000 vaccinated participants reported that maternal RSVpreF at 32–36 weeks of gestation was not associated with an increased risk of preterm birth9. However, this retrospective study showed that the hazard ratio of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) was 1.43 (95% CI 1.16–1.77). Generally, to investigate the risk of a rare outcome event between two cohorts, a large sample size is required to ensure enough power10,11. Therefore, a real-world data investigation with a larger sample size may strengthen the evidence regarding maternal safety outcomes following RSVpreF vaccination. This study aimed to evaluate the risk of maternal safety outcomes, including preterm birth, following RSVpreF vaccination during pregnancy compared with an unvaccinated cohort using large-scale real-world data.

Results

Participant characteristics

The search identified 11,265 and 363,263 pregnant women with and without RSVpreF vaccination, respectively, who had a healthcare encounter at 32–36 weeks of gestation. The participant characteristics before propensity score matching are presented in Table 1.

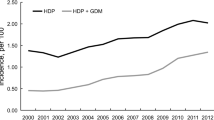

Before the matching, the mean age was 30.3 and 29.9 years in the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. The vaccinated group was more likely to be white (66.1% and 59.9% in the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, respectively) or Asian (12.7% and 5.5% in the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, respectively), whereas the unvaccinated group was more likely to be black or African–American (8.2% and 14.7% in the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, respectively). A higher prevalence of the following pre-existing underlying conditions was observed in the vaccinated group: obesity, multiparity, gestational diabetes (GDM), pregestational hypertension, edema, proteinuria or HDP, hemorrhage in early pregnancy, multiparity, infertility, kidney disease, migraine, cystitis, sexually transmitted infection, inflammation of vagina and vulva, placenta previa, history of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), high-risk pregnancy, tobacco and alcohol dependance, and immunocompromising conditions.

Base-case analysis

After matching, 11,265 participants remained in each cohort with a residual standard difference of <0.1 across all investigated covariates (Table 2). Each outcome event was observed in 351 (3.1%) and 358 (3.2%) for preterm delivery, 3130 (27.8%) and 3099 (27.5%) for HDP, 158 (1.4%) and 204 (1.8%) for oligohydramnios, 125 (1.1%) and 126 (1.1%) for placental abruption, 930 (8.3%) and 985 (8.7%) for IUGR, and 19 (0.2%) and 28 (0.2%) for intrauterine fetal death (IUFD) in the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, respectively (Table 3). The odds ratios (ORs) of primary outcomes in the vaccinated group compared with the unvaccinated group were 0.98 [0.84–1.142]; p = 0.789 for preterm delivery, 1.01 [0.96–1.08]; p = 0.644 for HDP, 0.98 [0.90–1.06]; p = 0.570 for GDM, 0.77 [0.63–0.95]; p = 0.015 for placental abruption, 0.94 [0.86–1.03]; p = 0.189 for IUGR, and 0.68 [0.38–1.22]; p = 0.189 for IUFD, respectively. The ORs of the secondary outcomes were 1.30 [0.73–2.33]; p = 0.376 for neurological diseases, 1.59 [0.87–2.92]; p = 0.131 for ITP, 0.60 [0.32–1.14]; p = 0.114 for myocarditis or pericarditis, 0.81 [0.62–1.05]; p = 0.110 for venous thrombosis. The outcomes of maternal death, eclampsia, and anaphylaxis could not be evaluated due to their small number of outcome event (<=10) in either arm.

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Tables 1–7), the risks of primary outcomes were not statistically increased, except for HDP. The OR of HDP was significantly high in some scenarios (OR 1.09 [1.03–1.15]; p = 0.005 by changing the gestational week period to 28–36, OR 1.08 [1.01–1.16]; p = 0.030, by limiting the study period between September 2024 and January 2025, and OR 1.16 [1.11–1.20]; p < 0.001 by limiting the definition of the RSV vaccination to the procedure code only).

Discussions

This study compared the maternal safety outcomes following RSVpreF using real-world data. The lack of increased risk of the defined maternal outcomes following RSVpreF vaccination compared with the unvaccinated group in the base-case scenario further strengthened the safety evidence of maternal RSV vaccination. On the other hand, the increased risk of HDP was observed following RSV vaccination in some scenarios in the sensitivity analyses.

A systematic review indicated that the risk of preterm birth may increase following the maternal RSV vaccination (RR 1.16 [95% CI 0.99–1.36]) with uncertain evidence12. In a recently published study using real-world data from the US, preterm birth was reported in 5.9 and 6.7% of vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts, respectively9. The lower rates of preterm delivery in both the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts in our study may have been due to the difference in the study population (i.e., two centers in New York in the recently published study vs. 27 healthcare organizations in our study for the vaccinated cohort). The preterm birth rate among mothers with RSV vaccination in relevant literature ranged from 2.2% in a systematic review to 8.5% in a single-center study (a university hospital)2,9,12,13,14,15,16. Unpublished data from the Vaccine Safety Datalink in the US also showed that the maternal RSV vaccination at 32–36 weeks of gestation did not increase the risk of preterm birth (OR 0.90 (95%CI 0.80–1.00))13. Our study provides further evidence that nonadjuvanted bivalent recombinant RSV vaccination during pregnancy may not be associated with preterm delivery.

In our study, the nonadjuvanted bivalent recombinant RSV vaccination was not associated with HDP, including preeclampsia in our base-case analysis. While the trend of reduction in preeclampsia was observed in the vaccinated group, the increased OR of HDP was observed in some sensitivity analyses. The evaluation of these outcomes is particularly important because, in a clinical trial, preeclampsia was reported in 1.8% of the vaccinated group and 1.4% of the unvaccinated group2. In addition, a recent US study showed an increased hazard ratio of HDP in their vaccinated group9. This study suggested that the association of HDP may have been due to insurance type and study site. Unfortunately, our study could not evaluate the impact of study site or insurance type, both of which could have been critical factors for the observed HDP results. We could not evaluate all potential confounders in this study. Therefore, a potential of residual confounders remained. This is particularly important because participant characteristics, including race and comorbidities, were significantly different between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups in our study. Although the observed OR of HDP in the vaccinated group of our sensitivity analyses was not very high (i.e., point estimates ranging approximately 1.0–1.1), our study and these relevant studies indicated the need to further investigate the association (e.g., different databases and populations outside of the US).

Our study showed a decreasing trend in oligohydramnios in the vaccinated group. While some well-known factors associated with the outcomes were adjusted using propensity score matching, as in other relevant studies9,14, we could not remove the possibility of unadjusted confounders, including socioeconomic factors and insurance type, in this study. Another potential reason that could partly explain the reduction in oligohydramnios following RSVpreF vaccination is the reduced maternal RSV infection through the protection of the vaccination. Some studies indicated that maternal viral infection was associated with oligohydramnios17,18. Although the infantile protective impact of the maternal RSVpreF vaccination has been reported2, the maternal protective impact of the maternal RSVpreF vaccination has not been evaluated yet. Future studies should evaluate the impact of maternal RSVpreF vaccination on maternal RSV infection and its associated outcomes, which could be a unique benefit of maternal vaccination compared to infantile monoclonal antibody administration.

In our sensitivity analysis that limited participants with an index event between September 2024 and January 2025, participants outside of the maternal RSV vaccination season in the US were excluded. This sensitivity analysis removed the potential impact of zero or few probabilities of exposure by season on the outcome events. This was particularly important if the outcome events were affected by season.

This study has important implications for RSV prevention strategies in infants. In the US, all infants are recommended to be immunized with either maternal vaccination or infantile monoclonal antibodies19. The selection of maternal RSV vaccination and/or infantile monoclonal antibody immunization in each country is highly dependent on its effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness20,21,22. Reassuring maternal safety outcomes using real-world data can be important in devising a national strategy for RSV prevention in young infants.

This study had some limitations. First, we could not evaluate neonatal outcomes because of the inability to tether maternal data with their neonates, as well as the inability to review neonatal outcomes, given the restrictive regulations of TriNetX. Although the study was solely limited to maternal safety outcomes, it provides additional evidence regarding the safety outcomes of RSVpreF using a large-scale real-world database. Second, although our study was one of the largest to date on this topic, we could not investigate the risk of rare events following vaccination. Some outcomes investigated in our study were observed in <5% of participants in both arms. To further evaluate the risk of very rare events (e.g., stillbirth and eclampsia), a much larger sample size is required23. Third, we could not evaluate any countries outside of the United States because of the much smaller doses of maternal RSV vaccines and the lack of documentation of vaccination with corresponding gestational week codes within the TriNetX database. Given that the clinical trial data suggest that the risk of preterm birth following RSVpreF may be lower in higher-income countries (e.g., the United States) than in lower-income countries (e.g., South Africa), real-world data regarding the safety outcomes of RSVpreF during pregnancy in lower-income countries further strengthen its global evidence and widespread use worldwide24. Fourth, within the TriNetX platform, only one statistical analysis (i.e., propensity score matching with a 1:1 greedy nearest-neighbor method) was available without individual patient-level data access. Therefore, the robustness of the statistical findings in this study could not be confirmed by other statistical methods. Fifth, we needed to rely on ICD-10 codes to identify medical comorbidities and outcomes, which could lead to misclassifications in some participants. For example, relying on ICD-10 codes only could lead to under-ascertainment of preterm delivery. This needs to be considered to appropriately interpret our study results.

In summary, using a large-scale global database, our study demonstrated that maternal RSV pre-vaccination did not increase the risk of selected maternal outcome events, except for HDP. While there was no statistical association between HDP and the vaccination in the base-case analysis, the sensitivity analyses indicated a small but increased risk of HDP following vaccination in some scenarios. Because we could not evaluate some potentially important factors, including insurance type and study site, the results need to be interpreted with caution. This added safety evidence for maternal RSV vaccination, potentially contributing to the widespread global use of the RSVpreF vaccine during pregnancy. Future studies should include post-licensure effectiveness and safety assessments in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

Study design and setting

This retrospective cohort study evaluated the maternal safety outcomes of the RSVpreF vaccine during pregnancy using TriNetX, a large-scale global database with electronic health records of more than 180,000,000 patients as of June 2025, with the US as a major contributor to the global database25. TriNetX is a population-based database funded by a ranged of investors. TriNetX allows patient-level data analysis, whereas access to population-level aggregated data is permitted for researchers. TriNetX contains de-identified data from electronic health records, including patient demographics, diagnoses based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes, procedures, medication, and healthcare visits. Using TriNetX, researchers can generate two cohorts and conduct propensity score matching to compare outcomes. In the TriNetX global database, approximately 1.69 million patients received any antenatal or delivery care as of November 2025. The distribution of participants by region is presented in Supplementary Table 8. Because all vaccinated participants with the corresponding gestational week code were from the United States, all of the following evaluations were conducted for the US participants.

Cohort building

The study participants were pregnant women who had a healthcare encounter at 32 0/7–36 6/7 weeks of gestation (when the maternal RSVpreF vaccine was recommended in the US) between September 1st 2023, and July 15th, 2025. Two cohorts were generated to compare maternal safety outcomes after propensity score matching. Details of the cohort-building strategy are provided in Supplementary Table 9 and Supplementary Table 10. The RSVpreF-vaccinated cohort consisted of pregnant women who received the RSVpreF vaccine at 32–36 weeks of gestation, whereas the unvaccinated group included pregnant women who had a healthcare encounter at 32–36 weeks of gestation but did not receive the RSVpreF vaccine at any time.

Outcomes

Maternal safety outcomes investigated in this study were selected based on relevant studies2,9,12,13,14,15. Primary (obstetric) outcomes included maternal death, preterm delivery, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, HDP (a composite of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and eclampsia), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), oligohydramnios, placental abruption, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and intrauterine fetal death (IUFD). Secondary non-obstetric outcomes included anaphylaxis, neuroinflammatory or demyelinating disorders (i.e., encephalitis, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome), immune thrombocytopenic purpura, myocarditis or pericarditis, and venous thrombosis13. The follow-up period was from the following day to 120 days after the index event. The index event was defined as RSVpreF vaccination (prescription and administration) and the first health encounter between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation for the vaccinated cohort and the first health encounter between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation for the unvaccinated cohort. The first health encounter between 32 and 36 weeks referred to their first healthcare visit to a TriNetX-participating organization with a corresponding gestational week code for both groups. All outcome events and patient comorbidities were extracted based on ICD-10 codes (Supplementary Table 11).

Ethics

The TriNetX’s database is compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and General Data Protection Regulation26, While de-identified TriNetX studies do not need Institutional Review Board approval according to the HIPAA privacy rule27. The Institutional Review Board of Nara Prefecture General Medical Center approved the publication of this study, and informed consent was not required (approval No. 1029).

Statistical analysis

A sample size calculation was then performed. The required minimal sample size to detect a statistical significance of an outcome event with an OR of 1.2 in the RSVpreF group compared with the unvaccinated group, 5% of outcome events in the unvaccinated group, case:control ratio of 1:1, alpha 0.05, and power 0.8, was estimated as 9157 in each arm for the two-sided test.

In the TriNetX platform, propensity score matching was implemented using a 1:1 greedy nearest-neighbor method and a caliper with 0.1 pooled standard deviations, aiming for differences between propensity scores <0.1. The matching order was determined by randomizing the order of participants before matching28. Covariates for propensity score matching included age group, race, obesity, multiple gestations (e.g., twin pregnancy), and nulliparity, as well as a history of preterm labor, IUGR, high-risk pregnancy, infertility, hemorrhage in early pregnancy, placenta previa, psychoactive substance use, sexually transmitted infections, genital infection, diabetes, hypertensive disorders and associated conditions, and migraine and kidney diseases, given the reported risk factors of preterm labor, preeclampsia, and eclampsia in published literature13,29,30,31,32. The window period for counting these comorbidity diagnoses was between 5 years and 1 day before the index event. Following propensity score matching, the two cohorts were compared for the risk of each outcome event to calculate the OR with a 95% CI. Cohort building, data extraction, and data analysis were implemented on the TriNetX platform, and sample size estimation was conducted using Stata MP 18.0.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted as follows;

-

by expanding the exposure window period from 32 to 36 weeks to 28–36 weeks, and to 34–36 weeks of gestation to explore the impact of a potential difference in the timing of the index event.

-

by limiting participants with an index event between September 2024 and January 2025 to evaluate the impact of vaccination year and seasonality

-

by extending the outcome follow-up period to include the same day as the index event (i.e., between the same day and 120 days after the index event),

-

by excluding those who already had events associated with outcomes (i.e., preterm labor, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, IUGR, and IUFD) before 32 weeks of gestation during their current pregnancy,

-

by including pre-existed four comorbidities (preterm labor, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, IUGR, and IUFD) in the factors of propensity score matching

-

by redefining the RSV vaccination as the procedure code only (excluding the prescription code).

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article or supplementary material. Individual-level data were not available because of TriNetX regulations. Searching terms to build cohorts are presented in Supplementary Tables. Individual-level data are not available due to the regulation of TriNetX. Additional analyses are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Li, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 2047–2064 (2022).

Kampmann, B. et al. Bivalent prefusion F vaccine in pregnancy to prevent RSV illness in infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1451–1464 (2023).

Hammitt, L. L. et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in healthy late-preterm and term infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 837–846 (2022).

Madhi, S. A. et al. A Phase 1b/2a trial of a half-life extended respiratory syncytial virus neutralizing antibody, Clesrovimab, in healthy preterm and full-term infants. J. Infect. Dis. 231, e478–e487 (2025).

Terstappen, J. et al. The respiratory syncytial virus vaccine and monoclonal antibody landscape: the road to global access. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, e747–e761 (2024).

Pecenka, C. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination and immunoprophylaxis: realising the potential for protection of young children. Lancet 404, 1157–1170 (2024).

Fleming-Dutra, K. E. et al. Use of the Pfizer respiratory syncytial virus vaccine during pregnancy for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus-associated lower respiratory tract disease in infants: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 72, 1115–1122 (2023).

Dodd, C. et al. Methodological frontiers in vaccine safety: qualifying available evidence for rare events, use of distributed data networks to monitor vaccine safety issues, and monitoring the safety of pregnancy interventions. BMJ Glob. Health 6, e003540 (2021).

Son, M. et al. Nonadjuvanted bivalent respiratory syncytial virus vaccination and perinatal outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2419268 (2024).

Sagar, A. S., Bashoura, L., Nasim, F. & Grosu, H. B. Assessing the safety of rare events: the importance of sample size. J. Bronchol. Inter. Pulmonol. 26, e30 (2019).

Godolphin, P. J. et al. Outcome assessment by central adjudicators in randomised stroke trials: simulation of differential and non-differential misclassification. Eur. Stroke J. 5, 174–183 (2020).

Phijffer, E. W. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination during pregnancy for improving infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5, CD015134 (2024).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). RSVpreF vaccine, preterm birth, and small for gestational age at birth preliminary results from the vaccine safety Datalink. https://www.cdc.gov/acip/downloads/slides-2024-10-23-24/03-RSV-Mat-Peds-DeSilva-508.pdf (2024).

Hsieh, T. Y. J., Wei, J. C. & Collier, A. R. Investigation of maternal outcomes following respiratory syncytial virus vaccination in the third trimester: insights from a real-world United States electronic health records database. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 233, e181–e190 (2025).

Blauvelt, C. A. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccine and nirsevimab uptake among pregnant people and their neonates. JAMA Netw. Open 8, e2460735 (2025.

Torres-Torres, J. et al. Maternal RSV vaccination for infant protection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of phase 3 trials with an integrated economic evaluation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.70641 (2025).

Kurmanova, G. et al. Post COVID-19 impact on perinatal outcomes. Diagnostics 15, 57 (2024).

Rahman, J. & Pervin, S. Maternal complications and neonatal outcomes in oligohydramnios. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 11, 310–314 (2022).

Kemp, M., Capriola, A. & Schauer, S. RSV immunization uptake among infants and pregnant persons—Wisconsin, October 1, 2023-March 31, 2024. Vaccine 47, 126674 (2025).

Boundy, E. O. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus immunization coverage among infants through receipt of nirsevimab monoclonal antibody or maternal vaccination—United States, October 2023-March 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 74, 484–489 (2025).

Dugdale, C., Santos, E. & Ciaranello, A. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination in pregnancy: safety, efficacy, and global implications. Obstet. Gynecol. 145, 144–146 (2025).

Hodgson, D. et al. Protecting infants against RSV disease: an impact and cost-effectiveness comparison of long-acting monoclonal antibodies and maternal vaccination. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 38, 100829 (2024).

Biau, D. J., Kernéis, S. & Porcher, R. Statistics in brief: the importance of sample size in the planning and interpretation of medical research. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466, 2282–2288 (2008).

Madhi, S. A. et al. Preterm birth frequency and associated outcomes from the MATISSE (maternal immunization study for safety and efficacy) maternal trial of the bivalent respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine. Obstet. Gynecol. 145, 147–156 (2025).

Palchuk, M. B. et al. A global federated real-world data and analytics platform for research. JAMIA Open 6, ooad035 (2023).

Stein, E., Hüser, M., Amirian, E. S., Palchuk, M. B. & Brown, J. S. TriNetX dataworks-USA: overview of a multi-purpose, de-identified, federated electronic health record real-world data and analytics network and comparison to the US census. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 34, e70198 (2025).

Olaker, V. R. et al. With big data comes big responsibility: strategies for utilizing aggregated, standardized, de-identified electronic health record data for research. Clin. Transl. Sci. 18, e70093 (2025).

Ludwig, R. J. et al. A comprehensive review of methodologies and application to use the real-world data and analytics platform TriNetX. Front. Pharm. 16, 1516126 (2025).

Crowe, H. M., Wesselink, A. K., Hatch, E. E., Wise, L. A. & Jick, S. S. Migraine and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a population-based cohort study. Cephalalgia 43, 3331024231161746 (2023).

Fox, R., Kitt, J., Leeson, P., Aye, C. Y. L. & Lewandowski, A. J. Preeclampsia: risk factors, diagnosis, management, and the cardiovascular impact on the offspring. J. Clin. Med. 8, 1625 (2019).

Elawad, T. et al. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia in clinical practice guidelines: comparison with the evidence. BJOG 131, 46–62 (2024).

US Department of Health and Human Services and National Institutes of Health. What are the risk factors for preterm labor and birth? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/preterm/conditioninfo/who_risk (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank TriNetX for their technical assistance. This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP23K27865 and JP23KK0298 and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) JP24fk0108709.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. designed the study, and extracted and analyzed data, T.S., S.T., H.F., and S.Y. contributed to the data interpretation and visualization. The manuscript was written by T.K., with intellectual oversight and guidance from T.S., S.T., H.F., and S.Y. The manuscript was submitted on behalf of all authors by T.K. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Kitano has received grants from the Japan Foundation for Pediatric Research, Public Promoting Association, and BioMérieux. Dr. Tsuzuki received grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the Japan Institute for Health Security, and Honoraria from Gilead Sciences. Dr. Fukuda received a grant from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). Dr. Yoshida received grants from Tauns Laboratories and Mizuho Medy. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kitano, T., Sado, T., Tsuzuki, S. et al. Maternal safety outcomes of respiratory syncytial vaccination during pregnancy with a large-scale database. npj Vaccines 11, 53 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-026-01373-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-026-01373-4