Abstract

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have shown to be effective in reducing the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), serving as a crucial barrier to the transmission of ARGs through wastewater. However, the risk of those ARGs remaining in the effluent requires further investigation. In this study, influent and effluent samples from WWTPs with different process configurations were collected for metagenomic sequencing. A total of 1331 ARG subtypes were detected in influent, with total abundance ranged from 0.46 to 3.89 copies/cell, which was higher than global level. The total abundance of ARGs was effectively reduced in effluent with removal efficiency 63.2–94.2%, resulting in a relatively low level when compared with other cities worldwide. Despite the effectiveness in reducing the abundance of ARGs, 4.38% ARGs remaining in effluent were identified as Rank I by arg_ranker with APH(3”)-Ib, ere(A), and sul1 as the most abundant subtypes. Further, metagenomic assembly showed that these high-risky ARGs co-occurred with mobile genetic elements (transposase, recombinase, relaxase, and integrase) and were primarily carried by WHO priority pathogens (Salmonella enterica and Pseudomonas aeruginosa), indicating their high-risky potentials. Taken together, these results indicated that even though WWTPs effectively reduced the abundance of ARGs, the potential risks of remaining ARGs still cannot be neglected. These results might be helpful for controlling the spread of ARGs from WWTPs into neighboring ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) rapidly accumulate and spread in the environment due to the abuse of antibiotics1,2. In 2021, 4.71 million deaths were related to ARB globally GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance3 and this might increase to 10 million by 20504. The threats posed by ARB to public health are due to their ability to carry antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) that can withstand the effects of antibiotics and spread into other bacteria by mobile genetic elements (MGEs). In recent years, ARGs have been widely detected across diverse environments, attracting the attention of both scientists and governments5.

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are considered a crucial barrier to prevent the entry of ARGs into natural ecosystems6,7,8,9. The anaerobic/anoxic/aerobic (AAO) process is widely used in current WWTPs and it has been found to effectively reduce the abundance of ARGs10,11. As the standards for effluent became increasingly stringent, process configurations in WWTPs underwent technical improvement, such as modified AAO, cyclic activated system (CAST), and modified sequencing batch reactor (MSBR). These processes involved adding reaction tanks to the original reactors and adjusting operational parameters to enhance nitrogen and phosphorus removal12,13,14, while the effectiveness of these processes in ARGs removal is not clear. In addition to technological developments, further treatment was also utilized after the AAO process. Membrane bioreactor (MBR) could enhance biological treatment to reduce antibiotics in effluent15 and disinfection (e.g., chlorination, ultraviolet (UV)), on the other hand, could inactivate ARB through oxidation16. Alternatively, some classic process configurations are still being used in current WWTPs, such as Unitank and anoxic/aerobic (AO) process. The behaviors of ARGs within these processes have yet to be assessed, which needs a comprehensive investigation.

Even though the abundance of ARGs have been reduced in WWTPs, more and more researchers are realizing that the abundance of ARGs is not equal to their potential risks17,18. Considerable ARGs are not hosted by pathogenic bacteria or co-occurred with MGEs, and therefore, they are not necessarily regarded as potential risks to human health17,19. Recently, a practical risk ranking framework was developed that considered the existing environment, mobility, and host pathogenicity20. Therefore, despite the effectiveness in reducing the total abundance of ARGs, the risks of the ARGs remaining in effluent require evaluation to better understanding their potential threats to neighboring ecosystems.

In this study, influent and effluent samples were collected from WWTPs with different process configurations in a large city of China. The main research aims of this study were to: (1) compare the removal efficiency of ARGs and high-risky ARGs in WWTPs with different process configurations, (2) identify the high-risky ARGs remaining in effluent, and (3) reveal the co-occurrence of high-risky ARGs with MGEs and their bacterial hosts. Results of this study will enhance the understanding of ARG dynamics in WWTPs and highlight the potential risks of ARGs remaining in effluent.

Results

Diversity and abundance of ARGs in the WWTPs

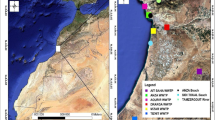

In this study, influent and effluent samples were collected from seven municipal WWTPs with different process configurations (Fig. S1). A total of 25 types of ARGs were detected, with 1331 subtypes in influent and 373 subtypes in effluent. There was significant seasonal variation in the ARG subtypes both in influent (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05) and effluent (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.01) (Fig. S2) with a greater number of ARG subtypes in winter. The dominant types of ARGs were observed to be distinct in influent and effluent (Fig. 1a). Beta-lactam resistance gene (abundance 17.1%) and aminoglycoside resistance gene (abundance 16.4%) were the dominant types in influent while in effluent, most abundant ARG type belonged to multidrug resistance gene (abundance 18.7%), bacitracin resistance gene (abundance 17.9%), and sulfonamide resistance gene (abundance 14.0%) (Fig. 1a). To assess the abundance of ARGs at global scale, influent (n = 137, Table S1) and effluent (n = 76, Table S2) samples from worldwide WWTPs were selected for comparison. In this study, the abundance of ARGs in influent was 0.46–3.89 copies/cell (average 2.59 copies/cell) (Fig. 1b), which was higher than selected influent samples worldwide (average 1.63 copies/cell, Fig. 1c). After treatment, the abundance of ARGs was significantly reduced to 0.17–0.63 copies/cell (average 0.30 copies/cell) in effluent (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.01, Fig. 1b), which was lower than global average level (average 0.52 copies/cell, Fig. 1d). These results indicated that a relatively low level of ARGs were released by these WWTPs to neighboring ecosystems.

Removal of ARGs in WWTPs with different process configurations

In this study, the abundance of ARGs in influent decreased substantially by 88.4% (63.2–94.2% in each WWTP, Fig. 2a, Table S3) and significant reductions in the major types of ARGs also occurred from influent to effluent (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05, Fig. 2b). The AAO process was widely used in current WWTPs and it achieved a removal efficiency of 87.7% (WWTP BJ and WWTP KG_AAO). The removal efficiency of modified AAO (WWTP BG and WWTP KX, 91.3%) was higher than that of AAO while the AAO coupled with MBR (AAO-MBR) process showed no obvious improvement (WWTP DY, 87.9%) (Fig. 2a, Table S3). The CAST and MSBR parallel (CAST/MSBR) process (WWTP ZJ 88.1%) and AO (WWTP KG_AO 87.6%) processes also showed similar removal efficiencies with that of AAO process. Notably, the classic process configuration (Unitank, WWTP CB) exhibited the lowest efficiency (81.4%) and achieved only 63.2% in summer (Fig. 2a, Table S3). In addition, different disinfection processes were used for advanced treatment in some WWTPs. The removal efficiency of modified AAO process with UV (WWTP KX, 87.7%) was lower than that without UV (WWTP BG, 93.8%) while chlorination (WWTP KG_AAO, 87.7%) did not exhibit higher efficiency compared to that without chlorination (WWTP BJ, 87.8%) (Fig. 2a, Table S3).

Redundancy analysis (RDA) followed by hierarchical partitioning analysis was used to identify the major environmental drivers influencing the profiles of ARGs (Fig. S3). In influent, antibiotics was the most significant factor (oxolinic acid, 35.3%; sulfamethoxazole, 20.3%; ofloxacin, 19.5%) while in effluent, ammonia-nitrogen (NH4+-N) was the most important contributor (41.9%), followed by total phosphorus (TP) (28.1%). These results indicated that antibiotics posed more effects on profiles of ARGs in influent than effluent.

Risks of ARGs remaining in effluent

An omics-based framework (arg_ranker) was used to evaluate the risk of each ARG20. Among all the ARG subtypes detected in the samples, 116 were classified as Rank I, and 98 as Rank II, representing 7.93% and 8.47% of the total abundance of ARGs, respectively. The largest proportion of the ARGs, however, fell into Rank IV, which accounted for 62.16% of the total abundance of ARGs. The aminoglycoside resistance gene was the most abundant ARG type in Rank I, making up nearly half (43.5%) of the total abundance of Rank I ARGs. In Rank II, the aminoglycoside resistance gene (27.5%) and the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin resistance gene (32.7%) contributed similar proportions to the total abundance of Rank II ARGs, with both being the dominant ARG types in this rank (Figs. S4, S5). In the influent samples, 9.70% and 10.88% of the total abundance of ARGs were classified as Rank I and Rank II, respectively. Their abundances were obviously decreased in the effluent, with reductions of 80.5% for Rank I and 85.7% for Rank II ARGs (Fig. 3, Table S3). Consequently, only 4.38% and 3.61% of total ARGs were identified as Rank I and Rank II in the effluent, respectively. These results showed that the WWTPs were effective in reducing the abundances of Rank I and Rank II ARGs. However, the removal efficiency of Rank I ARGs was slightly lower than that of the total ARGs, especially in winter seasons (72.4%) (Figs. 2a, 3, Table S3), showing that Rank I ARGs might be more stable in WWTPs.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used to evaluate the profiles of ARGs (Figs. 4, S6). The profiles of ARGs in influent and effluent were distinct from each other despite the seasonality (Fig. S6). Moreover, samples from the same risky ranks were grouped together, while samples from different risky ranks were clearly separated. This tendency was observed for both influent and effluent in different seasons (Fig. 4), showing that the different risky ranks of ARGs exhibited distinct distribution patterns.

In this study, after the wastewater treatment processes, most of the ARGs in effluent were identified as relatively low abundances (<10−5 copies/cell). The top 10 most abundant ARG subtypes in effluent were selected to further evaluate their potential risks (Fig. 5a). Among them, three subtypes of ARGs (APH(3”)-Ib, ere(A), and sul1) were identified as Rank I, accounting to 25.5%, 25.8%, and 7.2% of their abundances, respectively (Fig. 5a). Metagenomic assembly revealed that these three high-risky ARG subtypes co-occurred with MGEs (transposase, recombinase, relaxase, integrase) and carried by two WHO priority pathogens (Salmonella enterica and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (Fig. 5b, Table S4), showing their high-risky potentials. Notably, in WWTP CB, the abundances of Rank I APH(3”)-Ib (123.6% in winter season) and Rank I sul1 (2.1% in summer season, 21.1% in winter season) were observed to be increased in effluent compared with influent. Similarly, Rank I APH(3”)-Ib was also enriched in WWTP BJ (13.7% in winter season) (Figs. S7, S8, Table S3). These results highlighted that the risks of these ARGs remaining in effluent cannot be neglected.

Discussion

In this study, sampling of influent and effluent samples from WWTPs with different process configurations was carried out and a total of 1331 subtypes and 373 subtypes were detected in influent and effluent respectively. The number of ARG subtypes was significantly higher in winter samples than in summer samples (Fig. S2). Similarly, the abundance of ARGs in winter influent (average 2.73 copies/cell) was also higher than that in summer influent (average 2.39 copies/cell). Similar observation was reported elsewhere21 and might be related to increased use of antibiotics for illness in winter.

The dominant types of ARGs were observed to be distinct in influent and effluent (Fig. 1a). The most abundant ARG types in influent were beta-lactam, and aminoglycoside resistance genes, while multidrug, bacitracin, and sulfonamide resistance genes were the most dominant ARG types in effluent. Beta-lactam, and aminoglycoside were widely used antibiotics in China and they were detected in diverse ecosystems22,23,24. In addition, diverse multidrug resistance genes (e.g., qacEdelta1, qacH, qacE, mexK) and bacitracin resistance (e.g., bacA) were reported to be resistant to disinfectants25,26, which might be responsible for their high abundances in effluent. Typical sulfonamide resistance genes (sul1) were found to be easily transferred among different bacteria with MGEs (intI1), probably resulting in its high abundance of effluent27.

According to a previous study, the total abundance of ARGs in effluent could be divided into four exposure levels which were Level 1 (>1 copies/cell), Level 2 (0.5–1 copies/cell), Level 3 (0.25–0.5 copies/cell) and Level 4 (<0.25 copies/cell)28. Most of the effluent samples belonged to Level 3 or Level 4 (Fig. 1d), indicating a relatively low level of ARGs released by WWTPs to neighboring ecosystems. A global view of ARGs in WWTPs was obtained by collecting the available data in NCBI (Tables S1, S2). The results confirmed that the abundances of ARGs in effluent were lower than the global average abundance (Fig. 1d) while the total abundance of ARGs in influent was higher (Fig. 1c).

The ARG profiles in influent and effluent were compared by PCoA and they were clearly separated despite the seasonal difference (Fig. S6). This finding was consistent with a previous study, which also observed differences in ARG profiles between influent and effluent29. RDA showed that antibiotics had a stronger influence on the ARG profiles of influent (78.6%) than effluent (24.5%) (Fig. S3). This might be due to the higher concentration of antibiotics in influent (266.26–671.72 ng/L) than in effluent (46.44–257.93 ng/L) (Tables S5, S6, S7), which exerted greater selective pressure on bacteria30,31. A previous study confirmed this by showing that antibiotics in wastewater acted as a selective driver to promote the proliferation of ARGs32.

The total abundance of ARGs was significantly reduced from influent to effluent in WWTPs (Fig. 1b), with an efficiency of 88.4% (Fig. 2a, Table S3). The removal efficiency was higher than that previously reported in Japan29, USA33 and Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (China)34, but slightly lower than a study collected samples from WWTPs in Shandong and Gansu Province (China)35. Meanwhile, the dominant types of ARGs were also observed to be reduced significantly (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b), which was in alignment with a previous study36. The removal efficiencies of Rank I (80.5%) and Rank II (85.7%) ARGs were slightly lower than that of the total ARGs (88.4%) (Figs. 2a, 3, Table S3), probably due to their abilities for horizontal gene transfer. Meanwhile, the removal efficiency of Rank I ARGs (80.5%) was lower than that of Rank II (85.7%). This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that most of the pathogenic bacteria were gram-negative with lipopolysaccharide in cell walls to combat against ultraviolet or chlorinated disinfection37.

In this study, the removal efficiency of ARGs in AAO and AO processes with the same influent (WWTP KG) was compared. No obvious differences in removal efficiency for total and Rank I ARGs were observed between the AAO process (87.7% for total ARGs, 83.0% for Rank I ARGs) and the AO process (87.6% for total ARGs, 84.5% for Rank I ARGs) (Figs. 2a, 3, Table S3). In WWTPs, reduction of ARGs mainly depended on activated sludge to capture ARGs38, and therefore, additional anaerobic tank might not enhance the removal efficiency for ARGs29. Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in the removal efficiency of ARGs between CAST/MSBR (WWTP ZJ, 88.1% for total ARGs, 75.7% for Rank I ARGs) and AAO (WWTP BJ, 87.8% for total ARGs, 77.0% for Rank I ARGs) (Figs. 2a, 3, Table S3), which may also be attributed to the similar activated sludge processes for capturing ARGs. On the contrary, the Unitank process (WWTP CB) showed the lowest removal efficiency on total abundance of ARGs (81.4%) as well as Rank I ARGs (50.2%) (Figs. 2a, 3, Table S3). The Unitank process was equipped with aeration facilities in each tank, which might hinder the adsorption of ARGs by activated sludge11. Furthermore, the removal efficiency of modified AAO (WWTP BG and KX) was compared with that of AAO (WWTP BJ and KG_AAO) and modified AAO (91.3%) process showed higher than that of AAO (87.7%) (Fig. 2a, Table S3). Similarly, the removal efficiency of modified AAO (88.4%) on the removal of Rank I ARGs was better than that of AAO (80.1%) (Fig. 3, Table S3). The modified AAO process was equipped with a pre-anoxic tank to enhance nitrogen removal, which was found to be beneficial for removal of ARGs11,12,39. In addition, there was no obvious difference between AAO-MBR (WWTP DY, 87.9%) and AAO (WWTP KG_AO 87.7%) on removal efficiency of total ARGs (Fig. 2a, Table S3). This was inconsistent with a previous study that showed that abundance of ARGs after AAO-MBR treatment were significantly lower than AAO without MBR27. The influent of WWTP DY was combined with domestic wastewater and the presence of hazardous chemicals (e.g., Pb) in industrial wastewater might affect the removal efficiency of ARGs40.

In addition to biological treatment processes, the disinfection process was also considered promising for the removal of ARGs for its ability to kill microorganisms. In this study, the removal efficiency of AAO process with UV (WWTP KX, 87.7%) was lower to that without UV (WWTP BG, 93.8%) (Fig. 2a, Table S3). Similarly, the WWTP with chlorination (WWTP KG_AAO, 87.7%) also showed no obviously improved efficiency than the WWTP without chlorination (WWTP BJ, 87.8%) (Fig. 2a, Table S3). This limitation might be due to insufficient disinfection doses and contact time. A previous study found that the removal efficiency of ARGs increased with higher doses of UV irradiation41. To achieve effective removal, UV irradiation doses typically needed to exceed 200 mJ/cm2 41, which was much higher than the national standard (20 mJ/cm²) in China. The insufficient irradiation time could kill the bacteria and release intracellular ARGs, thereby increasing the ARGs in effluent and reducing the removal efficiency. To achieve effective removal of ARGs, the chlorination dosage needed to exceed 15 mg/L, which is higher than current WWTPs in China42. In addition, in this WWTP with chlorination (WWTP KG_AAO), the removal efficiency of total ARGs (87.7%) was higher than that of Rank I (83.0%) and Rank II (84.2%) ARGs (Figs. 2a, 3, Table S3). This was reasonable since the chlorination disinfection could promote the horizontal gene transfer of ARGs43,44, resulting in a lower removal efficiency on reducing Rank I and II ARGs.

In this study, risky ranks of each ARG was identified using arg_ranker20. PCoA plot was employed to assess the profiles of ARGs (Fig. 4). Samples categorized within the same risk rank were clustered together, while samples from different risk ranks displayed clear separation (Fig. 4), indicating that the distribution variations of ARGs among the different risk ranks exhibited distinct patterns. In this study, 116 and 98 ARG subtypes were identified as Rank I and Rank II, respectively, with only 22 subtypes being shared between the two ranks. The relatively low proportion of shared ARG subtypes suggested that the profiles of Rank I and Rank II ARGs were distinct, which could explain the separation observed in the PCoA plot. A previous study also showed the composition and profiles of Rank I and Rank II ARGs in wastewater samples was different7.

In this study, three subtypes of ARGs (APH(3”)-Ib, ere(A), and sul1) were identified as the Rank I ARGs with relatively high abundances (among top 10) remaining in effluent (Fig. 5a). Among them, Rank I sul1 showed an increase in abundance in WWTP CB in summer (2.1%) and winter (21.1%) seasons, while Rank I APH(3”)-Ib was enriched in WWTP BJ (13.7%) and WWTP CB (123.6%) in winter season (Figs. S7, S8, Table S3). Similarly, a previous study observed that the abundances of sul1 doubled in influent after treatment27. Moreover, these ARGs were found to co-occur with multiple MGEs and hosted by WHO priority pathogens (Salmonella enterica, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (Fig. 5b). This indicated their high-risky potentials and might accumulate in receiving rivers of WWTPs, bringing long-term potential health risks. A previous study indicated WWTPs contributed 87.3% of ARGs to downstream river water, where co-occurrence of ARGs (ere(A), sul1) and MGEs (transposase) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa was observed in both effluent and receiving river9. Another study found a large number of pathogens (including Salmonella and Pseudomonas) in a WWTP harbored a variety of ARGs (including sul1) and MGEs (insert sequence, transposase) coexisting in the plasmids and chromosomes45. In addition, the abilities of horizontal gene transfer for these ARGs has been proved in several studies46,47,48,49. A previous study found that APH(3”)-Ib can be transferred horizontally to confer resistance to aminoglycoside46. A similar study in aquaculture environments revealed that sul1 and APH(3”)-Ib were transferred horizontally, resulting in antibiotic resistance in pathogens47. This suggested that although the abundance of ARGs can be significantly reduced in WWTPs, the risks in effluent were still not negligible. In future studies, special attentions need to be paid on these high-risky ARGs and explore their behaviors in receiving ecosystems.

In conclusion, this study analyzed the removal efficiency and potential risks of ARGs in WWTPs with different process configurations. Effective reductions (88.4%) in the total abundance of ARGs was observed and Rank I ARGs were removed with slightly lower efficiency (80.5%). Moreover, 4.38% ARGs remaining in effluent were identified as Rank I with APH(3”)-Ib, ere(A), and sul1 as the most abundant subtypes. Metagenomic assembly revealed that these ARGs coexisted with multiple MGEs (transposase, recombinase, relaxase, integrase) and harbored by two WHO priority pathogens (Salmonella enterica and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Together, these results indicated that although WWTPs reduced the abundance of ARGs, the potential risks of the residual ARGs in effluent still required further attentions.

Methods

Sample collection

Seven municipal WWTPs with different process configurations in Nanjing, China were selected as the sampling sites (Fig. S1), with the distances between the plants ranging from 10.7 km to 53.4 km. These WWTPs mainly received the domestic wastewater except WWTP DY, which collected both domestic wastewater and industrial wastewater from two adjacent industrial parks (Table S8). Influent (~1 L) and effluent (~2 L) samples were collected from these WWTPs during summer (temperature 23 to 31 °C) and winter (temperature −2 to 14 °C) seasons. After collection, all of the samples were transported to the laboratory within 6 h and processed for physiochemical analyses immediately upon arrival.

Physiochemical analyses

The pH was measured using a multiparameter analyzer (Mettler, Switzerland). The samples were digested with K2S2O8 before total nitrogen (TN) and TP analysis. TN, TP, and NH4+-N were determined colorimetrically using a multiparameter water quality tester (Luheng, China). Metal concentrations (Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Zn) were determined using ICP-MS (Perkin Elmer, USA). The physicochemical attributes were listed in Table S9.

For antibiotics analyses, 500 mL influent sample or 1 L effluent sample was filtered through a 0.22 μm polycarbonate membrane. After filtration, the pH of each sample was adjusted to about 3.050. Antibiotics were extracted using the solid-phase extraction (SPE) with Oasis HLB cartridges (Waters, USA). The cartridges were preconditioned by flushing them with 6 mL methanol, followed by 3 mL ultrapure water, and then 6 mL sodium dihydrogen phosphate solution (100 g/L). The samples passed through the preconditioned SPE cartridges at a flow rate of 5–10 mL/min. The analytes were eluted using 6 mL methanol and 6 mL ammonia (2%) in methanol. The extract was evaporated to <1 mL and the enriched samples were reconstituted in 1 mL methanol and finally analyzed on a UHPLC-MS/MS (Agilent Technologies, USA). The detection limits for antibiotics ranged from 0.05 to 1.51 ng/L and the quantitation limits ranged from 0.2 to 6.03 ng/L (Table S10). The antibiotic data were listed in Tables S5, S6, S7.

Genomic DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing

About 0.5 L influent sample or 1 L effluent sample was filtered through a 0.22 μm polycarbonate membrane. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was used for library construction with an insert size of 350 bp. Metagenomic sequencing was performed on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform at Novogene (Tianjin, China) using a paired-end 150 bp strategy.

Quantification, global comparison, and risk assessment of ARGs

The quality of raw data was assessed using FastQC (version 0.11.9)51. Low-quality reads and Illumina adapters were removed to obtain clean reads using Fastp (version 0.23.1)52. The ARGs-OAP pipeline (version 2.3) was utilized to annotate and quantify ARGs from the clean reads53. Potential ARG sequences were identified by comparing against the SARG database (version 2.3) using BLASTX with an e-value ≤ 10−7, a similarity ≥80%, and an alignment length percentage ≥75%54,55. The relative abundance of ARGs was normalized by the copy number of bacterial cells (copies/cell).

To compare the abundance of ARGs from WWTPs worldwide, the metagenomic sequencing data was collected from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), including 137 influent samples from Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America (Table S1) and 76 effluent samples from Asia, Europe, North America, and South America (Table S2). The abundances of ARGs in these samples were analyzed using the same method as described above.

The arg_ranker (version 3.0) was applied to assess the risks of ARGs20. This framework assigned the risk of ARGs into four ranks (Rank I, II, III, and IV) based on anthropogenic prevalence, gene mobility, and the potential pathogenicity of the host bacteria20.

Metagenomic assembly and identification of ARGs and MGEs

Metagenomic assembly was applied to reveal the co-occurrence of ARGs and MGEs. The clean reads were assembled into contigs using MEGAHIT with default parameters (version 1.2.9)56. Then the open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted from these contigs using Prodigal (version 2.6.3)57. To optimize computational efficiency, redundancy within the predicted ORFs was removed using MMseqs2 (version 15.6f452)58, applying stringent thresholds (≥ 95% sequence similarity and alignment length percentage ≥90%). The non-redundant ORFs were then used for annotation to identify ARGs and MGEs using ARGs-OAP pipeline (version 2.3) and mobileOG (version 1.1.3), respectively53,59.

Statistical analyses

All following analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.2). The abundances of ARGs in influent and effluent was compared by the Wilcoxon test using the ‘wilcoxmed’ package (version 0.0–1)60. PCoA based on ‘Bray-Curtis’ distance was conducted to reveal the profiles of total ARGs and risky ARGs using the ‘vegan’ package (version 2.6–4)61. RDA was performed to reveal the effects of environmental attributes on ARGs using the ‘vegan’ package (version 2.6–4)61. The individual contribution of each factor was determined by hierarchical partitioning analysis with the ‘rdacca.hp’ package (version 1.1-0)62.

Data availability

The metagenomic sequencing data have been submitted to the Genome Sequence Archive (https://www.cncb.ac.cn/) under the accession number CRA018575.

Code availability

The codes generated and/or used in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Borrow, R. et al. Global Meningococcal Initiative: Insights on antibiotic resistance, control strategies and advocacy efforts in Western Europe. J. Infect. 89, 106335 (2024).

Aslam, B. et al. AMR and sustainable development goals: at a crossroads. Glob. Health 20, 73 (2024).

GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborator. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 404, 1199–1226 (2024).

Arega Negatie, B., Ajulo, S. & Awosile, B. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS 2022): investigating the relationship between antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial consumption data across the participating countries. PLoS ONE 19, e0297921 (2024).

Bertagnolio, S. et al. WHO global research priorities for antimicrobial resistance in human health. Lancet Microbe 5, 100902 (2024).

Manoharan, R. K., Ishaque, F. & Ahn, Y.-H. Fate of antibiotic resistant genes in wastewater environments and treatment strategies - A review. Chemosphere 298, 134671 (2022).

Wu, Y., Gong, Z., Wang, S. & Song, L. Occurrence and prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes and pathogens in an industrial park wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 880, 163278 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Mass-immigration shapes the antibiotic resistome of wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168193 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Wastewater treatment plant effluents exert different impacts on antibiotic resistome in water and sediment of the receiving river: metagenomic analysis and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 460, 132528 (2023).

Mao, D. et al. Prevalence and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes in two municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 85, 458–466 (2015).

Ping, Q. et al. The prevalence and removal of antibiotic resistance genes in full-scale wastewater treatment plants: bacterial host, influencing factors and correlation with nitrogen metabolic pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 827, 154154 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Performance of a full-scale modified anaerobic/anoxic/oxic process: high-throughput sequence analysis of its microbial structures and their community functions. Bioresour. Technol. 220, 225–232 (2016).

Liu, C., Qian, K. & Li, Y. Diagnostic method for enhancing nitrogen and phosphorus removal in cyclic activated sludge technology (CAST) process wastewater treatment plant. Water 14, 2253 (2022).

Askari, S. S. et al. Enhancing sequencing batch reactors for efficient wastewater treatment across diverse applications: a comprehensive review. Environ. Res. 260, 119656 (2024).

Zheng, W., Wen, X., Zhang, B. & Qiu, Y. Selective effect and elimination of antibiotics in membrane bioreactor of urban wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 646, 1293–1303 (2019).

Xu, L., Zhang, C., Xu, P. & Wang, X. C. Mechanisms of ultraviolet disinfection and chlorination of Escherichia coli: Culturability, membrane permeability, metabolism, and genetic damage. J. Environ. Sci. 65, 356–366 (2018).

Martínez, J. L., Coque, T. M. & Baquero, F. What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 116–123 (2014).

Qian, H., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Q., Lu, T. & Zhu, Y.-G. Abundance cannot represent antibiotic resistance risk. Soil Ecol. Lett. 4, 291–292 (2022).

D’Costa, V. M. et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 477, 457–461 (2011).

Zhang, A.-N. et al. An omics-based framework for assessing the health risk of antimicrobial resistance genes. Nat. Commun. 12, 4765 (2021).

Bonanno Ferraro, G. et al. Characterisation of microbial communities and quantification of antibiotic resistance genes in Italian wastewater treatment plants using 16S rRNA sequencing and digital PCR. Sci. Total Environ. 933, 173217 (2024).

Song, Y., Han, Z., Song, K. & Zhen, T. Antibiotic consumption trends in China: evidence from six-year surveillance sales records in Shandong Province. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 491 (2020).

Lambert, H. et al. Prevalence, drivers and surveillance of antibiotic resistance and antibiotic use in rural China: Interdisciplinary study. PLOS Glob. Public Health 3, e0001232 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. Antibiotics: an overview on the environmental occurrence, toxicity, degradation, and removal methods. Bioengineered 12, 7376–7416 (2021).

Alcock, B. P. et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D690–D699 (2022).

Jia, S. et al. Bacterial community shift drives antibiotic resistance promotion during drinking water chlorination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 12271–12279 (2015).

Wang, F. et al. Fates of antibiotic resistance genes during upgrading process of a municipal wastewater treatment plant in southwest China. Chem. Eng. J. 437, 135187 (2022).

Yin, X. et al. An assessment of resistome and mobilome in wastewater treatment plants through temporal and spatial metagenomic analysis. Water Res. 209, 117885 (2022).

Honda, R. et al. Transition of antimicrobial resistome in wastewater treatment plants: impact of process configuration, geographical location and season. npj Clean. Water 6, 46 (2023).

Rodriguez-Mozaz, S. et al. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hospital and urban wastewaters and their impact on the receiving river. Water Res. 69, 234–242 (2015).

Wang, P. et al. Triclosan facilitates the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes during anaerobic digestion: focusing on horizontal transfer and microbial response. Bioresour. Technol. 413, 131522 (2024).

Garner, E. et al. Metagenomic profiling of internationally sourced sewage influents and effluents yields insight into selecting targets for antibiotic resistance monitoring. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 16547–16559 (2024).

Majeed, H. J. et al. Evaluation of metagenomic-enabled antibiotic resistance surveillance at a conventional wastewater treatment plant. Front. Microbiol. 12, 657954 (2021).

Shi, B. et al. Metagenomic surveillance of antibiotic resistome in influent and effluent of wastewater treatment plants located on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 870, 162031 (2023).

Sun, H. et al. Deciphering the antibiotic resistome and microbial community in municipal wastewater treatment plants at different elevations in eastern and western China. Water Res. 229, 119461 (2023).

Tavares, R. D. S., Fidalgo, C., Rodrigues, E. T., Tacão, M. & Henriques, I. Integron-associated genes are reliable indicators of antibiotic resistance in wastewater despite treatment- and seasonality-driven fluctuations. Water Res. 258, 121784 (2024).

Livermore, D. M. Current epidemiology and growing resistance of gram-negative pathogens. Korean J. Intern. Med. 27, 128 (2012).

Xu, Y.-B. et al. Distribution of tetracycline resistance genes and AmpC β-lactamase genes in representative non-urban sewage plants and correlations with treatment processes and heavy metals. Chemosphere 170, 274–281 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. Evaluation of various carbon sources on ammonium assimilation and denitrifying phosphorus removal in a modified anaerobic-anoxic-oxic process from low-strength wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 171890 (2024).

Ding, H. et al. Characterization of antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial community in selected municipal and industrial sewage treatment plants beside Poyang Lake. Water Res. 174, 115603 (2020).

McKinney, C. W. & Pruden, A. Ultraviolet disinfection of antibiotic resistant bacteria and their antibiotic resistance genes in water and wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 13393–13400 (2012).

Yuan, Q. B., Guo, M. T. & Yang, J. Fate of antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes during wastewater chlorination: implication for antibiotic resistance control. PLoS ONE 10, e0119403 (2015).

Jin, M. et al. Chlorine disinfection promotes the exchange of antibiotic resistance genes across bacterial genera by natural transformation. ISME J. 14, 1847–1856 (2020).

Liu, S.-S. et al. Chlorine disinfection increases both intracellular and extracellular antibiotic resistance genes in a full-scale wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 136, 131–136 (2018).

Shi, L., Zhang, J., Lu, T. & Zhang, K. Metagenomics revealed the mobility and hosts of antibiotic resistance genes in typical pesticide wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 817, 153033 (2022).

Opazo-Capurro, A. et al. Co-occurrence of two plasmids encoding transferable blaNDM-1 and tet(Y) genes in carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter bereziniae. Genes 15, 1213 (2024).

Zhuang, M. et al. Horizontal plasmid transfer promotes antibiotic resistance in selected bacteria in Chinese frog farms. Environ. Int. 190, 108905 (2024).

Bonardi, S. et al. Emerging of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O177:H11 and O177:H25 from cattle at slaughter in Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 423, 110846 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Metagenomic survey reveals more diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater than hospital wastewater. Front. Microbiol. 12, 712843 (2021).

Osinska, A. et al. Small-scale wastewater treatment plants as a source of the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes in the aquatic environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 381, 121221 (2020).

Brown, J., Pirrung, M. & McCue, L. A. FQC Dashboard: integrates FastQC results into a web-based, interactive, and extensible FASTQ quality control tool. Bioinformatics 33, 3137–3139 (2017).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Yin, X. et al. ARGs-OAP v3.0: antibiotic-resistance gene database curation and analysis pipeline optimization. Engineering 32, 2346–2351 (2022).

Yin, X. et al. ARGs-OAP v2.0 with an expanded SARG database and Hidden Markov Models for enhancement characterization and quantification of antibiotic resistance genes in environmental metagenomes. Bioinformatics 34, 2263–2270 (2018).

Cock, P. J, Chilton, J. M, Grüning, B, Johnson, J. E & Soranzo, N NCBI BLAST+ integrated into Galaxy. GigaScience 4, s13742-13015-10080-13747 (2015).

Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinf. 11, 1–11 (2010).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1026–1028 (2017).

Brown, C. L. et al. mobileOG-db: a manually curated database of protein families mediating the life cycle of bacterial mobile genetic elements. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 88, e00991–00922 (2022).

Divine, G., Norton, H. J., Hunt, R. & Dienemann, J. A review of analysis and sample size calculation considerations for Wilcoxon tests. Anesthesia Analgesia 117, 699–710 (2013).

Oksanen, J. et al. Package ‘vegan’. Community ecology package. version 2, 1–295 (2013).

Lai, J., Zou, Y., Zhang, J. & Peres-Neto, P. R. Generalizing hierarchical and variation partitioning in multiple regression and canonical analyses using the rdacca. hp R package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 13, 782–788 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. James Walter Voordeckers for careful language editing. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U21A20179, 42307121, 42007302), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M742042), and Shandong Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. SDCX-ZG-2024001763).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.: Methodology, data analysis, investigation and writing—original draft. T.Z.: Investigation, supervision, and funding acquisition. M.M.: Review & editing. M.L.: Methodology and data analysis. S.X.: Conceptualization, supervision, validation, writing—review & editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, C., Zhang, T., Mustafa, M.F. et al. Removal efficiency of ARGs in different wastewater treatment plants and their potential risks in effluent. npj Clean Water 8, 45 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00456-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00456-4

This article is cited by

-

A Review of the Prevalence and Resistance Profiles of Bacteria in Hospital Wastewater in Iran: Implications for Public Health

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2025)