Abstract

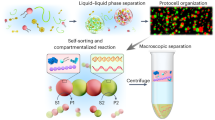

The bottom-up construction of cell-like entities or protocells is essential for emulating cytomimetic behaviours within artificial cell consortia. Complex coacervate microdroplets are promising candidates for primordial cells; however, replicating the complex cellular organization and cell–cell interactions using membraneless coacervates remains a major challenge. To address this, we developed membrane-bound coacervate protocells by interfacial assembly of metal–organic framework nanoparticles around coacervate microdroplets. By leveraging the inherently porous structure and surface chemistry of metal–organic frameworks, we demonstrated the ability to regulate biomolecular organization within the protocells and integrate proteins into the membrane, thereby imitating both integral and peripheral membrane proteins. These membranized coacervates were further engineered into artificial-organelle-incorporated protocells and tissue-like assemblies capable of signal processing and protocell-to-protocell communication. Our findings highlight the potential of designing artificial systems with spatially controlled biomolecular organization to mimic natural cellular functions, paving the way for the assembly of membranized coacervates into prototissues.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mann, S. Systems of creation: the emergence of life from nonliving matter. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 2131–2141 (2012).

Guindani, C., Brunsveld, L. C., Cao, S., Ivanov, T. & Landfester, K. Synthetic cells: from simple bio-inspired modules to sophisticated integrated systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202110855 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Enzyme-free synthesis of natural phospholipids in water. Nat. Chem. 12, 1029–1034 (2020).

Elani, Y., Law, R. V. & Ces, O. Vesicle-based artificial cells as chemical microreactors with spatially segregated reaction pathways. Nat. Commun. 5, 5305 (2014).

Rifaie-Graham, O. et al. Photoswitchable gating of non-equilibrium enzymatic feedback in chemically communicating polymersome nanoreactors. Nat. Chem. 15, 110–118 (2023).

Sun, J. et al. Morphogenesis of starfish polymersomes. Nat. Commun. 14, 3612 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. Oscillating the local milieu of polymersome interiors via single input-regulated bilayer crosslinking and permeability tuning. Nat. Commun. 13, 585 (2022).

Gobbo, P. et al. Programmed assembly of synthetic protocells into thermoresponsive prototissues. Nat. Mater. 17, 1145–1153 (2018).

Huang, X. et al. Interfacial assembly of protein–polymer nano-conjugates into stimulus-responsive biomimetic protocells. Nat. Commun. 4, 2239 (2013).

Rodriguez-Arco, L., Li, M. & Mann, S. Phagocytosis-inspired behaviour in synthetic protocell communities of compartmentalized colloidal objects. Nat. Mater. 16, 857–863 (2017).

Li, M., Harbron, R. L., Weaver, J. V., Binks, B. P. & Mann, S. Electrostatically gated membrane permeability in inorganic protocells. Nat. Chem. 5, 529–536 (2013).

Wu, H., Du, X., Meng, X., Qiu, D. & Qiao, Y. A three-tiered colloidosomal microreactor for continuous flow catalysis. Nat. Commun. 12, 6113 (2021).

Dupin, A. & Simmel, F. C. Signalling and differentiation in emulsion-based multi-compartmentalized in vitro gene circuits. Nat. Chem. 11, 32–39 (2019).

Tian, D. et al. Multi-compartmental MOF microreactors derived from Pickering double emulsions for chemo-enzymatic cascade catalysis. Nat. Commun. 14, 3226 (2023).

Dupin, A. et al. Synthetic cell-based materials extract positional information from morphogen gradients. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9228 (2022).

Yang, Z., Wei, J., Sobolev, Y. I. & Grzybowski, B. A. Systems of mechanized and reactive droplets powered by multi-responsive surfactants. Nature 553, 313–318 (2018).

Kumar, B., Patil, A. J. & Mann, S. Enzyme-powered motility in buoyant organoclay/DNA protocells. Nat. Chem. 10, 1154–1163 (2018).

Xu, Z., Hueckel, T., Irvine, W. T. M. & Sacanna, S. Transmembrane transport in inorganic colloidal cell-mimics. Nature 597, 220–224 (2021).

Kurihara, K. et al. A recursive vesicle-based model protocell with a primitive model cell cycle. Nat. Commun. 6, 8352 (2015).

Adamala, K. & Szostak, J. W. Competition between model protocells driven by an encapsulated catalyst. Nat. Chem. 5, 495–501 (2013).

Kurihara, K. et al. Self-reproduction of supramolecular giant vesicles combined with the amplification of encapsulated DNA. Nat. Chem. 3, 775–781 (2011).

De Franceschi, N., Barth, R., Meindlhumer, S., Fragasso, A. & Dekker, C. Dynamin A as a one-component division machinery for synthetic cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 70–76 (2024).

Zhan, P., Jahnke, K., Liu, N. & Gopfrich, K. Functional DNA-based cytoskeletons for synthetic cells. Nat. Chem. 14, 958–963 (2022).

Lee, K. Y. et al. Photosynthetic artificial organelles sustain and control ATP-dependent reactions in a protocellular system. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 530–535 (2018).

Gao, N. et al. Chemical-mediated translocation in protocell-based microactuators. Nat. Chem. 13, 868–879 (2021).

Qiao, Y., Li, M., Booth, R. & Mann, S. Predatory behaviour in synthetic protocell communities. Nat. Chem. 9, 110–119 (2016).

Joesaar, A. et al. DNA-based communication in populations of synthetic protocells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 369–378 (2019).

Mansy, S. S. et al. Template-directed synthesis of a genetic polymer in a model protocell. Nature 454, 122–125 (2008).

Bhattacharya, A., Cho, C. J., Brea, R. J. & Devaraj, N. K. Expression of fatty acyl-CoA ligase drives one-pot de novo synthesis of membrane-bound vesicles in a cell-free transcription–translation system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11235–11242 (2021).

Koga, S., Williams, D. S., Perriman, A. W. & Mann, S. Peptide–nucleotide microdroplets as a step towards a membrane-free protocell model. Nat. Chem. 3, 720–724 (2011).

Fares, H. M., Marras, A. E., Ting, J. M., Tirrell, M. V. & Keating, C. D. Impact of wet–dry cycling on the phase behavior and compartmentalization properties of complex coacervates. Nat. Commun. 11, 5423 (2020).

Nakashima, K. K., van Haren, M. H. I., Andre, A. A. M., Robu, I. & Spruijt, E. Active coacervate droplets are protocells that grow and resist Ostwald ripening. Nat. Commun. 12, 3819 (2021).

Donau, C. et al. Active coacervate droplets as a model for membraneless organelles and protocells. Nat. Commun. 11, 5167 (2020).

Abbas, M., Lipinski, W. P., Nakashima, K. K., Huck, W. T. S. & Spruijt, E. A short peptide synthon for liquid–liquid phase separation. Nat. Chem. 13, 1046–1054 (2021).

Mashima, T. et al. DNA-mediated protein shuttling between coacervate-based artificial cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115041 (2022).

Tian, L. et al. Spontaneous assembly of chemically encoded two-dimensional coacervate droplet arrays by acoustic wave patterning. Nat. Commun. 7, 13068 (2016).

Deng, J. & Walther, A. Programmable and chemically fueled DNA coacervates by transient liquid–liquid phase separation. Chem 6, 3329–3343 (2020).

Deng, N. N. et al. Macromolecularly crowded protocells from reversibly shrinking monodisperse liposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7399–7402 (2018).

Xu, C., Martin, N., Li, M. & Mann, S. Living material assembly of bacteriogenic protocells. Nature 609, 1029–1037 (2022).

Cao, S. et al. Dipeptide coacervates as artificial membraneless organelles for bioorthogonal catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 39 (2024).

Choi, S., Meyer, M. O., Bevilacqua, P. C. & Keating, C. D. Phase-specific RNA accumulation and duplex thermodynamics in multiphase coacervate models for membraneless organelles. Nat. Chem. 14, 1110–1117 (2022).

Mu, W. et al. Superstructural ordering in self-sorting coacervate-based protocell networks. Nat. Chem. 16, 158–167 (2024).

Wu, H. & Qiao, Y. Engineering coacervate droplets towards the building of multiplex biomimetic protocells. Supramol. Mater. 1, 100019 (2022).

Dora Tang, T. Y. et al. Fatty acid membrane assembly on coacervate microdroplets as a step towards a hybrid protocell model. Nat. Chem. 6, 527–533 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Giant coacervate vesicles as an integrated approach to cytomimetic modeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2866–2874 (2021).

Mason, A. F., Buddingh’, B. C., Williams, D. S. & van Hest, J. C. M. Hierarchical self-assembly of a copolymer-stabilized coacervate protocell. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17309–17312 (2017).

Li, J., Liu, X., Abdelmohsen, L., Williams, D. S. & Huang, X. Spatial organization in proteinaceous membrane-stabilized coacervate protocells. Small 15, e1902893 (2019).

Kelley, F. M., Favetta, B., Regy, R. M., Mittal, J. & Schuster, B. S. Amphiphilic proteins coassemble into multiphasic condensates and act as biomolecular surfactants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2109967118 (2021).

Ji, Y., Lin, Y. & Qiao, Y. Plant cell-inspired membranization of coacervate protocells with a structured polysaccharide layer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12576–12585 (2023).

Gao, N., Xu, C., Yin, Z., Li, M. & Mann, S. Triggerable protocell capture in nanoparticle-caged coacervate microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3855–3862 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Enzyme-mediated nitric oxide production in vasoactive erythrocyte membrane-enclosed coacervate protocells. Nat. Chem. 12, 1165–1173 (2020).

Zhao, C. et al. Membranization of coacervates into artificial phagocytes with predation toward bacteria. ACS Nano 15, 10048–10057 (2021).

Levental, I. & Lyman, E. Regulation of membrane protein structure and function by their lipid nano-environment. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 107–122 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. Fabrication of fibrillosomes from droplets stabilized by protein nanofibrils at all-aqueous interfaces. Nat. Commun. 7, 12934 (2016).

Bergmann, A. M. et al. Evolution and single-droplet analysis of fuel-driven compartments by droplet-based microfluidics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203928 (2022).

Rothe G. Technical Background and Methodological Principles of Flow Cytometry (Basel, Karger, 2009).

Liang, W. et al. Metal–organic framework-based enzyme biocomposites. Chem. Rev. 121, 1077–1129 (2021).

Lyu, F., Zhang, Y., Zare, R. N., Ge, J. & Liu, Z. One-pot synthesis of protein-embedded metal–organic frameworks with enhanced biological activities. Nano Lett. 14, 5761–5765 (2014).

Liang, W. et al. Enhanced activity of enzymes encapsulated in hydrophilic metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2348–2355 (2019).

Towne, V., Will, M., Oswald, B. & Zhao, Q. Complexities in horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of dihydroxyphenoxazine derivatives: appropriate ranges for pH values and hydrogen peroxide concentrations in quantitative analysis. Anal. Biochem. 334, 290–296 (2004).

Yin, Z., Tian, L., Patil, A. J., Li, M. & Mann, S. Spontaneous membranization in a silk‐based coacervate protocell model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202302 (2022).

Garenne, D. et al. Sequestration of proteins by fatty acid coacervates for their encapsulation within vesicles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13475–13479 (2016).

Mason, A. F. et al. Mimicking cellular compartmentalization in a hierarchical protocell through spontaneous spatial organization. ACS Central Science 5, 1360–1365 (2019).

Tanner, P. et al. Polymeric vesicles: from drug carriers to nanoreactors and artificial organelles. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 1039–1049 (2011).

Bryant, D. M. & Mostov, K. E. From cells to organs: building polarized tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 887–901 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (T2425001 and 22172007), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0480000 and XDB0960000), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (JQ24008), the CAS Youth Interdisciplinary Team, the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2507000), the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52221006) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (buctrc202015) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. led the project. Y.J. performed the experiments. Y.J. and Y.Q. conceived the experiments. Y.J., Y.L. and Y.Q. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks Lucas Caire da Silva, Alexander Mason and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Videos, Materials and methods, Figures 1–31, Tables 1–4 and references.

Supplementary Video 1

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the assembly of RhB@ZIF-8 nanoparticles (NPs) on the DL405-PAA-doped coacervate surface to form a continuous membrane. The movie was shown at ×40 of real-time speed at 5 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 10 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 2

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the oxidation of Amplex red mediated by GOx and HRP (doped with 10% FITC-HRP) in FITC-HRP@MOF-coated coacervates. The systems showed transient red fluorescence after adding glucose to initiate the reaction. The video was shown at ×50 of real-time speed at 5 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 12 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 3

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the oxidation of Amplex red mediated by GOx and HRP (doped with 10% FITC-HRP) in membraneless coacervates. The systems showed persistent red fluorescence after adding glucose to initiate the reaction. The video was shown at ×50 of real-time speed at 5 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 12 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 4

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the lipase-catalysed lysis of FDA to fluorescein in membraneless RITC-lipase-doped coacervates. The systems showed no production of green fluorescence. The video was shown at ×30 of real-time speed at 3 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 3 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 5

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the lipase-catalysed lysis of FDA to fluorescein in RhB@MOF-coated coacervates. The systems showed fast generation of green fluorescence. The video was shown at ×30 of real-time speed at 3 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 3 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 6

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the production of resorufin (red fluorescence) in RhB@MOF-coated hierarchical coacervates. With the addition of amylose, resorufin (red fluorescence) was produced. The video was shown at ×50 of real-time speed at 5 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 10 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 7

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the production of resorufin (red fluorescence) in the binary populations of RhB@MOF-coated PDDA/PAA coacervates and membraneless Prot/FA coacervates. With the addition of amylose, resorufin (red fluorescence) was produced, which was faster in MOF-coated hierarchical coacervates than in the mixed binary coacervate populations. The video was shown at ×50 of real-time speed at 5 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 10 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 8

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the assembly of RhB@MOF-coated FITC-PEI-doped coacervates into tissue-like structures. The video was shown at ×15 of real-time speed at 3 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 90 s, real time was shown at the top right. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Supplementary Video 9

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the production of resorufin (red fluorescence) in prototissues with enzyme-containing artificial organelles. With the addition of lactose, resorufin (red fluorescence) was produced in prototissues. β-gal, GOx and HRP were labelled with FITC-β-gal, RITC-GOx and Cy5-HRP, respectively. MOF membranes were labelled with RhB. The video was shown at ×50 of real-time speed at 5 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 16.5 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Supplementary Video 10

Fluorescence microscopy video showing the production of resorufin (red fluorescence) in prototissues with relocated enzymes on membrane. With the addition of lactose, resorufin (red fluorescence) was produced in prototissues. β-gal, GOx and HRP were labelled with FITC-β-gal, RITC-GOx and DL405-HRP, respectively. MOF membranes were labelled with fluorescein. The video was shown at ×50 of real-time speed at 5 frames per second. The total duration of recording was 16.5 min; real time was shown at the top right. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical Source Data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, Y., Lin, Y. & Qiao, Y. Interfacial assembly of biomimetic MOF-based porous membranes on coacervates to build complex protocells and prototissues. Nat. Chem. 17, 986–996 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01827-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01827-7

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in coacervate protocells from passive catalysts to chemically programmable systems

Communications Chemistry (2026)