Abstract

Accurately assessing future precipitation changes presents one of the greatest challenges of climate change. In the tropics, changes in the Hadley circulation are expected to considerably affect precipitation in dry subtropical and wet equatorial regions. However, while climate models project a robust weakening of the Northern Hemisphere circulation in the coming decades, currently, there is low confidence in the magnitude of such weakening and its impact on regional precipitation patterns. Here we use emergent constraint analyses and observation-based Hadley circulation strength changes to show that the projected circulation weakening will probably be larger than in current predictions. The more pronounced weakening of the flow results in a doubling of the subtropical precipitation increase compared with current forecasts, specifically over Asia, Africa and the Pacific Ocean. Our findings provide more accurate tropical circulation and precipitation projections and have considerable societal impacts, given the scarcity of water in subtropical regions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used in the manuscript are publicly available: CMIP6 data at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/ and CMIP5 data at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip5/.

Code availability

Codes used to calculate the meridional mass streamfunction and meridional gradient are available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7529584 (ref. 47), and the KE equation at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6434337 (ref. 48).

References

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Seager, R., Naik, N. & Vecchi, G. A. Thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms for large-scale changes in the hydrological cycle in response to global warming. J. Clim. 23, 4651–4668 (2010).

IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Allen, M. R. & Ingram, W. J. Constraints on future changes in climate and the hydrologic cycle. Nature 419, 224–232 (2002).

Muller, C. J. & O’Gorman, P. A. An energetic perspective on the regional response of precipitation to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 266–271 (2011).

He, J. & Soden, B. J. A re-examination of the projected subtropical precipitation decline. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 53–57 (2017).

Durack, P. J., Wijffels, S. E. & Matear, R. J. Ocean salinities reveal strong global water cycle intensification during 1950 to 2000. Science 336, 455–458 (2012).

Schurer, A. P., Ballinger, A. P., Friedman, A. R. & Hegerl, G. C. Human influence strengthens the contrast between tropical wet and dry regions. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104026 (2020).

Chou, C., Neelin, J. D., Chen, C. & Tu, J. Evaluating the ‘rich-get-richer’ mechanism in tropical precipitation change under global warming. J. Clim. 22, 1982–2005 (2009).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. The response of precipitation minus evapotranspiration to climate warming: why the ‘wet-get-wetter, dry-get-drier’ scaling does not hold over land. J. Clim. 28, 8078–8092 (2015).

Lu, J., Vecchi, G. A. & Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06805 (2007).

Bony, S. et al. Robust direct effect of carbon dioxide on tropical circulation and regional precipitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 447–451 (2013).

Chemke, R. & Polvani, L. M. Exploiting the abrupt 4 × CO2 scenario to elucidate tropical expansion mechanisms. J. Clim. 32, 859–875 (2019).

Kent, C., Chadwick, R. & Rowell, D. P. Understanding uncertainties in future projections of seasonal tropical precipitation. J. Clim. 28, 4390–4413 (2015).

Elbaum, E. et al. Uncertainty in projected changes in precipitation minus evaporation: dominant role of dynamic circulation changes and weak role for thermodynamic changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL097725 (2022).

Shepherd, T. G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nat. Geosci. 7, 703–708 (2014).

D’Agostino, R. & Lionello, P. Evidence of global warming impact on the evolution of the Hadley circulation in ECMWF centennial reanalyses. Clim. Dyn. 48, 3047–3060 (2017).

Chemke, R. & Polvani, L. M. Opposite tropical circulation trends in climate models and in reanalyses. Nat. Geosci. 12, 528–532 (2019).

Chemke, R. & Yuval, J. Human-induced weakening of the Northern Hemisphere tropical circulation. Nature 617, 529–532 (2023).

Vallis, G. K., Zurita-Gotor, P., Cairns, C. & Kidston, J. Response of the large-scale structure of the atmosphere to global warming. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 1479–1501 (2015).

Chemke, R. & Polvani, L. M. Elucidating the mechanisms responsible for Hadley cell weakening under 4 × CO2 forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090348 (2021).

Cox, P. M. et al. Sensitivity of tropical carbon to climate change constrained by carbon dioxide variability. Nature 494, 341–344 (2013).

Cox, P. M., Huntingford, C. & Williamson, M. S. Emergent constraint on equilibrium climate sensitivity from global temperature variability. Nature 553, 319–322 (2018).

Hall, A., Cox, P., Huntingford, C. & Klein, S. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 269–278 (2019).

Eyring, V. et al. Taking climate model evaluation to the next level. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 102–110 (2019).

Tokarska, K. B. et al. Past warming trend constrains future warming in CMIP6 models. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz9549 (2020).

Shiogama, H., Watanabe, M., Kim, H. & Hirota, N. Emergent constraints on future precipitation changes. Nature 602, 612–616 (2022).

Deser, C., Phillips, A., Bourdette, V. & Teng, H. Uncertainty in climate change projections: the role of internal variability. Clim. Dyn. 38, 527–546 (2012).

Grise, K. M. & Polvani, L. M. Understanding the time scales of the tropospheric circulation response to abrupt CO2 forcing in the Southern Hemisphere: seasonality and the role of the stratosphere. J. Clim. 30, 8497–8515 (2017).

Schwendike, J. et al. Local partitioning of the overturning circulation in the tropics and the connection to the Hadley and Walker circulations. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 1322–1339 (2014).

Staten, P. W., Grise, K. M., Davis, S. M., Karnauskas, K. & Davis, N. Regional widening of tropical overturning: forced change, natural variability, and recent trends. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 6104–6119 (2019).

Raiter, D., Galanti, E. & Kaspi, Y. The tropical atmospheric conveyor belt: a coupled Eulerian-Lagrangian analysis of the large-scale tropical circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086437 (2020).

Simpson, I. R. et al. Emergent constraints on the large-scale atmospheric circulation and regional hydroclimate: do they still work in CMIP6 and how much can they actually constrain the future? J. Clim. 34, 6355–6377 (2021).

O’Gorman, P. A. Sensitivity of tropical precipitation extremes to climate change. Nat. Geosci. 5, 697–700 (2012).

DeAngelis, A. M., Qu, X., Zelinka, M. D. & Hall, A. An observational radiative constraint on hydrologic cycle intensification. Nature 528, 249–253 (2015).

Li, G., Xie, S., He, C. & Chen, Z. Western Pacific emergent constraint lowers projected increase in Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 708–712 (2017).

Thackeray, C. W., DeAngelis, A. M., Hall, A., Swain, D. L. & Qu, X. On the connection between global hydrologic sensitivity and regional wet extremes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 11343–11351 (2018).

Thackeray, C. W., Hall, A., Norris, J. & Chen, D. Constraining the increased frequency of global precipitation extremes under warming. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 441–448 (2022).

Zhang, W., Furtado, K., Zhou, T., Wu, P. & Chen, X. Constraining extreme precipitation projections using past precipitation variability. Nat. Commun. 13, 6319 (2022).

Mitas, C. M. & Clement, A. Recent behavior of the Hadley cell and tropical thermodynamics in climate models and reanalyses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L01810 (2006).

Chemke, R. Future changes in the Hadley circulation: the role of ocean heat transport. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091372 (2021).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Trenberth, K. E. & Guillemot, C. J. Evaluation of the global atmospheric moisture budget as seen from analyses. J. Clim. 8, 2255–2280 (1995).

Peixoto, J. P. & Oort, A. H. Physics of Climate (American Institute of Physics, 1992).

Vallis, G. K. Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006).

Chemke, R. Streamfunction and meridional gradient calculations. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7529584 (2023).

Chemke, R. KE equation solution. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6434337 (2022).

Acknowledgements

R.C. acknowledges support from the Willner Family Leadership Institute for the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C. and J.Y. equally contributed to this work. R.C. analysed the data and together with J.Y. discussed and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Minghua Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Zonal mean projected precipitation changes.

The future changes in zonal mean precipitation (ΔP, black) and the relative contribution from changes in evaporation (ΔE, gray), mean moisture (vΔq, purple), mean circulation (qΔv, red) and eddy moisture flux (\(\Delta {v}^{{\prime} }{q}^{{\prime} }\), blue) as a function of latitude. The solid lines show the CMIP6 mean and shadings the ± standard deviation across models.

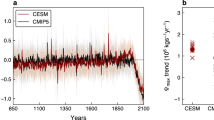

Extended Data Fig. 3 The lack of an emergent constraint in large ensembles.

The future changes in the Northern Hemisphere Hadley circulation strength (ΔΨmax) plotted against the 1960-2014 trends in Ψmax across the different members in a, ACCESS-ESM5, b, CanESM5, c, MIROC6 and d, MPI-ESM1-LR. The correlations appear in the upper left corners.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Linking future Hadley circulation strength changes.

The correlation coefficient across CMIP6 models of future changes in the Northern Hemisphere Hadley circulation strength (ΔΨmax) and 55-year trends in Ψmax starting at different years.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The role of internal variability.

a, The future changes in the Northern Hemisphere Hadley circulation strength (ΔΨmax) plotted against the 1960-2014 trends in Ψmax across CMIP6 models (blue dots). Blue line shows the linear regression. The green, black and purple lines respectively show the mean ΔΨmax in models, the observation-based 1960-2014 trend in Ψmax and the constrained ΔΨmax. The gray shading around the observation-based trend shows possible variations in the Hadley cell trend that arise from variations in the trend’s position within the models’ trend distribution (Methods). Purple shading around the constrained ΔΨmax shows the resulting uncertainty in the constrained ΔΨmax. b, The probability distributions of the observation-based 1960-2014 trend in Northern Hemisphere Ψmax (black) and of the 55-year Ψmax trends from preindustrial control runs, centered around the mean observation-based trend.

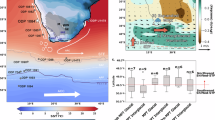

Extended Data Fig. 6 Constraining precipitation with historic flow trends.

The future changes (upper row) and 1960-2014 trends (bottom row) in zonal mean subtropical precipitation plotted against the 1960-2014 trends in a, d, Hadley circulation strength (Ψmax), b, e, sea-level pressure proxy (PSLy) and c, f, dynamically induced precipitation changes (qΔv) across CMIP6 models (blue dots). Blue lines show the linear regression and shadings the ± two standard deviations of the linear regressions (Methods). The black, purple and red lines respectively show the probability distributions of the observations, ΔP across models, and the constrained ΔP.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Projected precipitation changes.

The future changes in surface precipitation (mm day−1) in CMIP6 mean. Stippling shows regions where at least two thirds of the models agree on the sign of change. Gray rectangles show the areas of the regional analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Subtropical precipitation changes.

The future changes in subtropical precipitation (ΔPsubtropics, averaged over 15° − 30°N) plotted against the 1960-2014 trends in subtropical precipitation across CMIP6 models; their correlation appears in the upper left corner.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Future subtropical precipitation and circulation changes in CMIP5 models.

The future changes in Northern Hemisphere subtropical precipitation (ΔPsubtropics) plotted against the future changes in the Hadley circulation strength across CMIP5 models (blue dots); their correlation appears in the upper right corner. Blue line shows the linear regression and shading the ± two standard deviations of the linear regressions (Methods). The standard deviation across the models is used for the uncertainty in the regression coefficients.

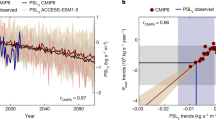

Extended Data Fig. 10 Hadley circulation strength changes in CMIP5.

a, The future changes in the Hadley circulation strength (ΔΨmax) plotted against the 1980-2034 trends in Ψmax across CMIP5 (blue dots) and CMIP6 (red dots) models; their correlations appear in the lower right corner. The blue and red lines show the linear regression in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models, respectively. b, The evolution of the Hadley cell strength (Ψmax) in the CMIP5 (blue line) and CMIP6 (red line) means.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–8 and Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chemke, R., Yuval, J. Atmospheric circulation to constrain subtropical precipitation projections. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 287–292 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02266-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02266-5

This article is cited by

-

Climate change shifts the North Pacific storm track polewards

Nature (2026)

-

Logarithmic CO2 warming reverses North Atlantic winter atmospheric circulation changes

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2026)

-

Seasonal emergence of human-caused expansion of the boreal tropical hydrological cycle

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Summer PM2.5 concentrations in the northern subtropics modulated by the Hadley circulation edge location

Climate Dynamics (2025)