Abstract

Escalating flood risks from climate change cause economic losses and alter migration patterns, although their impacts across socioeconomic groups remain underexplored. Here we investigate flood-induced inter-county migration in the United States between 2006 and 2019, and find that floods increase outflow and inflow migration by 2.7% and 1.9%, respectively. Younger, better-educated and employed residents leave, while older, less-educated and unemployed individuals move into affected counties. Such patterns can be amplified by media sentiment on flood risks. Selective migration lowers housing prices but raises rent, suggesting structural changes in flood-prone housing markets. Flood-induced selective migration also has salient impacts on the local labour markets, with net annual income losses estimated to be US$9.3 million and $1.98 million, conditional on education and age profiles, respectively. Our results shed light on how natural disasters influence selective migration conditional on socioeconomic profiles and how information provision interacts with migration incentives.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The migration data were obtained from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series of the Annual American Community Survey (https://usa.ipums.org/usa/acs.shtml). The flood data are available from the public website of the National Center for Environmental Information (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/). The housing market data are publicly available from the Zillow website (https://www.zillow.com/research/data/). The data on GDP, population size, unemployment rate and personal income data are publicly available from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (https://www.bea.gov/data). The public firm entry and exit data were obtained from the Augmented 10-X Header Database (https://sraf.nd.edu/sec-edgar-data/10-x-header-data/), which is publicly available. The information on government subsidies provided for post-flood economic recoveries is publicly available from the OpenFEMA Dataset (https://www.fema.gov/about/openfema/data-sets). The data on flood-related news articles were downloaded from the Dow Jones Factiva database (https://www.dowjones.com/professional/factiva/), which requires private subscription for access. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used for this analysis is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15254509 (ref. 53).

References

Dangendorf, S. et al. Acceleration of US Southeast and Gulf coast sea-level rise amplified by internal climate variability. Nat. Commun. 14, 1935 (2023).

Wing, O. E. et al. Inequitable patterns of US flood risk in the Anthropocene. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 156–162 (2022).

Marsooli, R., Lin, N., Emanuel, K. & Feng, K. Climate change exacerbates hurricane flood hazards along US Atlantic and Gulf Coasts in spatially varying patterns. Nat. Commun. 10, 3875 (2019).

Huang, X. & Swain, D. L. Climate change is increasing the risk of a California megaflood. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq0995 (2022).

Deryugina, T., Kawano, L. & Levitt, S. The economic impact of Hurricane Katrina on its victims: evidence from individual tax returns. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 10, 202–233 (2018).

Groen, J. A., Kutzbach, M. J. & Polivka, A. E. Storms and jobs: the effect of hurricanes on individuals’ employment and earnings over the long term. J. Labor Econ. 38, 653–685 (2020).

Billings, S. B., Gallagher, E. A. & Ricketts, L. Let the rich be flooded: the distribution of financial aid and distress after Hurricane Harvey. J. Financ. Econ. 146, 797–819 (2022).

Sajid, O. & Bevis, L. E. M. Flooding and child health: evidence from Pakistan. World Dev. 146, 105477 (2021).

Khanna, M. & Kochhar, N. Do marriage markets respond to a natural disaster? The impact of flooding of the Kosi river in India. J. Popul. Econ. 36, 2241 – 2276 (2023).

He, C. et al. Flood exposure and pregnancy loss in 33 developing countries. Nat. Commun. 15, 20 (2024).

Dessaint, O. & Matray, A. Do managers overreact to salient risks? Evidence from hurricane strikes. J. Financ. Econ. 126, 97–121 (2017).

Basker, E. & Miranda, J. Taken by storm: business financing and survival in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. J. Econ. Geogr. 18, 1285–1313 (2018).

Pankratz, N. M. & Schiller, C. M. Climate change and adaptation in global supply-chain networks. Rev. Financ. Stud. 37, 1729–1777 (2024).

Huynh, T. D. & Xia, Y. Panic selling when disaster strikes: evidence in the bond and stock markets. Manage. Sci. 69, 7448–7467 (2023).

Fleming, E. et al. in Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment Vol. II (eds Reidmiller, D.R. et al.) Ch. 8 (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2018).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

Devitt, L., Neal, J., Coxon, G., Savage, J. & Wagener, T. Flood hazard potential reveals global floodplain settlement patterns. Nat. Commun. 14, 2801 (2023).

Rigaud, K. K. et al. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration Tech. Rep. (World Bank, 2018).

Kocornik-Mina, A., McDermott, T. K., Michaels, G. & Rauch, F. Flooded cities. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 12, 35–66 (2020).

Dahl, K. et al. Underwater: rising seas, chronic floods, and the implications for US coastal real estate. Union of Concerned Scientists www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2018/06/underwater-analysis-full-report.pdf (2018).

Bohra-Mishra, P., Oppenheimer, M. & Hsiang, S. M. Nonlinear permanent migration response to climatic variations but minimal response to disasters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9780–9785 (2014).

Hornbeck, R. & Naidu, S. When the levee breaks: black migration and economic development in the American South. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 963–90 (2014).

Chen, J. J., Mueller, V., Jia, Y. & Tseng, S. K.-H. Validating migration responses to flooding using satellite and vital registration data. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 441–445 (2017).

Bernstein, A., Gustafson, M. T. & Lewis, R. Disaster on the horizon: the price effect of sea level rise. J. Financ. Econ. 134, 253–272 (2019).

Bernstein, A., Billings, S. B., Gustafson, M. T. & Lewis, R. Partisan residential sorting on climate change risk. J. Financ. Econ. 146, 989–1015 (2022).

Bakkensen, L. A. & Ma, L. Sorting over flood risk and implications for policy reform. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 104, 102362 (2020).

Drabo, A. & Mbaye, L. M. Natural disasters, migration and education: an empirical analysis in developing countries. Environ. Dev. Econ. 20, 767–796 (2015).

Sheldon, T. L. & Zhan, C. The impact of hurricanes and floods on domestic migration. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 115, 102726 (2022).

Richler, J. Nudge to flood insurance. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 906 (2019).

Niu, D., Eichholtz, P. & Kok, N. Asymmetric information provision and flood risk salience. J. Hous. Econ. 68, 102060 (2023).

Hino, M. & Burke, M. The effect of information about climate risk on property values. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2003374118 (2021).

Gourevitch, J. D. et al. Unpriced climate risk and the potential consequences of overvaluation in US housing markets. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 250–257 (2023).

Heger, M. P. & Neumayer, E. The impact of the Indian Ocean tsunami on Aceh’s long-term economic growth. J. Dev. Econ. 141, 102365 (2019).

Lee, S. Adapting to Natural Disasters Through Better Information: Evidence from the Home Seller Disclosure Requirement Research Paper No. 21/17 (MIT Center for Real Estate, 2023).

Callaway, B. & Sant’Anna, P. H. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J. Econom. 225, 200–230 (2021).

Baerlocher, D., Cortes, G. & Vinicios, S. Finding Home When Disaster Strikes: Dust Bowl Migration and Housing in Los Angeles Research Paper No. 24/13 (MIT Center for Real Estate, 2024).

Sisson, P. The other housing crisis: too many sick, aging homes. Bloomberg https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-11-27/america-s-aging-housing-stock-takes-toll-on-public-health?re_source=postr_story_2 (2023).

Lindersson, S. et al. The wider the gap between rich and poor the higher the flood mortality. Nat. Sustain. 6, 995–1005 (2023).

Fagan, B. M.The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations (Bloomsbury Press, 2008).

Daepp, M. I., Bunten, D. M. & Hsu, J. W. The effect of racial composition on neighborhood housing prices: evidence from Hurricane Katrina-induced migration. J. Urban Econ. 134, 103515 (2023).

Boustan, L. P., Kahn, M. E., Rhode, P. W. & Yanguas, M. L. The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in US counties: a century of data. J. Urban Econ. 118, 103257 (2020).

Vigdor, J. The economic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. J. Econ. Perspect. 22, 135–154 (2008).

Ellen, I. G. & Meltzer, R. Heterogeneity in the recovery of local real estate markets after extreme events: the case of Hurricane Sandy. Real Estate Econ. 52, 714–752 (2024).

Cheng, D. Climate influencers on social media. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 309 (2024).

Hu, Z. Social interactions and households’ flood insurance decisions. J. Financ. Econ. 144, 414–432 (2022).

Vilone, D. & Polizzi, E. Modeling opinion misperception and the emergence of silence in online social system. PLoS ONE 19, e0296075 (2024).

Mahrukh, R., Shakil, S. & Malik, A. S. Sentiments analysis of fMRI using automatically generated stimuli labels under naturalistic paradigm. Sci. Rep. 13, 7267 (2023).

Baker, A. C., Larcker, D. F. & Wang, C. C. How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? J. Financ. Econ. 144, 370–395 (2022).

Sun, L. & Abraham, S. Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J. Econom. 225, 175–199 (2021).

Marcus, M. & Sant’Anna, P. H. The role of parallel trends in event study settings: an application to environmental economics. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 8, 235–275 (2021).

Cengiz, D., Dube, A., Lindner, A. & Zipperer, B. The effect of minimum wages on low-wage jobs. Q. J. Econ. 134, 1405–1454 (2019).

Rambachan, A. & Roth, J. A more credible approach to parallel trends. Rev. Econ. Stud. 90, 2555–2591 (2023).

Fan, Y., Gao, Q., Sioh, Y. E. & Wan, W. X. Data and code for reproduction of ‘Post-flood selective migration interacts with media sentiment and income effects’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15254509 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank seminar participants at the National University of Singapore, Monash University, Deakin University, Queensland University of Technology, Asian Real Estate Society (AsRES) Annual Meeting 2023, Asian Bureau of Finance and Economics Research (ABFER) Annual Meeting 2024, SMU-Jinan Conference on Urban and Regional Economics 2024, and other conferences where authors presented this paper. This paper was previously circulated with the title ‘Gone with the Flood: Natural Disasters, Selective Migration, and Media Sentiment’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F., Q.G. and W.X.W. conceived the research question and developed the methodology. Q.G. and Y.E.S. contributed to the data curation. Q.G., Y.E.S. and W.X.W. performed the data analysis under the supervision of Y.F. and W.X.W. Y.E.S. wrote the first draft. Y.F. and W.X.W. led the revisions of the paper. Y.F., Q.G. and W.X.W. rewrote the paper. Y.F., Q.G., Y.E.S. and W.X.W. contributed to the refinement, interpretation and discussion of the analysis. All authors contributed equally to this article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Linguere Mbaye, Jianghao Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Correlation between Net Migration and Flood Risk in the US.

This figure shows (a) the net migration in the U.S. at the state level between 2006 and 2019 and (b) the average flood risk in the same period at the county level. Data on state-to-state migration flows is obtained from the United States Census Bureau; the National Flood Risk Index is obtained from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Both figures are generated using QGIS, keeping the same coordinate projection, and the base map is obtained from ESRI (https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=f16090f6d3da48ec8f144a0771c8fec4).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Conceptual Framework: Relationships among Flood Disasters, Media Sentiment, and Selective Migration.

This figure presents the conceptual framework in our study, illustrating the relationships of flood disasters, media sentiment, and selective migration.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Impact of Floods on Migration: Placebo Test Results.

This figure shows the distribution of the placebo-test estimates for the impacts of floods on (a) outflow migration and (b) inflow migration, respectively. For each flood event in a county, we randomly assign an event year as a placebo treatment, and we repeat this process 1,000 times to get the distribution. The y-axis in the figures represents the p-values of the estimates, and the horizontal dashed line refers to the 5% significance level. Statistical significance is determined using two-sided tests without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Event Study Results: Robustness Checks Using the Synthetic Control Approach.

This figure plots the estimated coefficients of the impact of flood events on outflow and inflow migration from the event study using Equation (1), with the synthetic control approach. Data are presented as mean values ± 95% confidence intervals. For both regressions, the total number of observations is 12824. Statistical significance is determined using two-sided tests without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

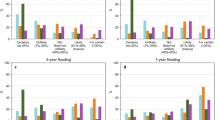

Extended Data Fig. 5 Selective Migration Patterns after Floods: Robustness Checks Using the Synthetic Control Approach.

This figure plots the estimated coefficients of the impact of flood events on (a) outflow migration and (b) inflow migration of different sociodemographic subgroups, using the synthetic control approach. Each estimate indicates the average change in outflow (or inflow) migration in the unit of log (number of migrants per year) in three years after the flood event, relative to the 3-year period before the flood event. High (low) education refers to migrants with degrees at or above (below) the college level. Employed (unemployed) individuals are classified by their employment status in 1 year before the flood. Young (old) individuals are those under (in or above) the age of 40. Data are presented as mean values ± 95% confidence intervals. For all regressions, the total number of observations is 12824. Statistical significance is determined using two-sided tests without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Correlation between Google Search Index of Flood and Number of News Articles.

This figure shows the correlation between the weekly Google search index (GSI) of the keyword ‘flood’ in the U.S. and the number of flood-related news articles in the Factiva database between 2005 and 2019. The GSI is obtained from https://trends.google.com/trends/.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Conceptual framework and hypothesis, robustness checks and Supplementary Tables 1–15.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Fig. 1a (Fig1_A_Pretrend_twfe) and 1b (Fig1_B_Pretrend_csdid).

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for Fig. 2a (Fig2_A_Selective_outmigration) and 2b (Fig2_B_Selective_inmigration).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 1a (ExtendedData_Fig1_A_State_to_state_migration) and 1b (ExtendedData_Fig1_B_Flood_risk).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 3a (ExtendedData_Fig3_A_PlaceboTest_out) and 3b (ExtendedData_Fig3_B_PlaceboTest_in).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 5a (ExtendedData_Fig5_A_SCM_outflow) and 5b (ExtendedData_Fig5_B_SCM_inflow).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Y., Gao, Q., Sitoh, Y.E. et al. Post-flood selective migration interacts with media sentiment and income effects. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 619–626 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02345-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02345-7