Abstract

The Southern Ocean mitigates global surface warming by taking up a large portion of the carbon released by human activities. While models suggest this carbon sink should weaken as climate change increases upwelling of carbon-rich deep water, such a decline has not been observed over the past decades. Here, using circumpolar hydrographic observations, we reveal that Southern Ocean freshening since the 1990s has enhanced density stratification, which prevents these CO2-enriched waters from reaching the surface. Meanwhile, the surface layer has become thinner, allowing the CO2-rich circumpolar deep water to get closer to the surface, replacing winter water between 100 m and 200 m. In this layer, the CO2 fugacity increased by ~10 µatm because of changing ocean dynamics since the 1990s. Our findings imply that the observed surface freshening temporarily buffered the model-predicted weakening of the Southern Ocean carbon sink, but that such a signal could potentially emerge if stratification weakened.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The Southern Ocean, south of 35° S, accounts for ~40% of the global oceanic uptake of anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2)1,2,3,4. Thus, it removes a disproportionally large share of anthropogenic CO2 from the atmosphere, making it a key ocean region for the mitigation of climate change3. The efficiency of this CO2sink is inherently linked to the Southern Ocean overturning circulation that allows exchanges of heat and carbon between the deep ocean and the surface5,6. As much as 80% of the global ocean’s deep water returns to the surface in this region7, carrying large amounts of pre-industrial dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) accumulated globally in the deep ocean over centuries8. This return pathway through the Southern Ocean is visible as a circumpolar band of high-CO2 waters at the subsurface9, reaching the surface south of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, where it induces a CO2 release to the atmosphere and controls the amount of anthropogenic CO2 entering the surface ocean while these waters are transported northwards10.

Previous studies have suggested that an intensification of the Southern Ocean overturning circulation would profoundly weaken the future carbon sink11,12. Model simulations indicate that increasing atmospheric CO2 and ozone depletion, with some contribution of natural variability, lead to a poleward intensification of westerly winds13,14,15, which is reflected in a more positive phase of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM)16,17. This strengthening of the winds leads to an intensification of the upper overturning circulation cell of the Southern Ocean, which has already been observed and attributed to human-induced changes in recent modelling and observational studies18,19. Subsequently, the enhanced wind-driven upwelling is expected to increase the vertical supply of carbon-rich deep waters to the surface and the CO2 outgassing of the region20,21, reducing its uptake capacity of anthropogenic CO2. Accordingly, biogeochemical models12, atmospheric inversions11,22 and ship-based observations23 detected a weakening of the carbon sink into the mid-2000s. Simulations of future climate consistently predict a trend towards stronger westerly winds24,25 and an expected further weakening or stagnation of the Southern Ocean carbon sink11.

On the other hand, observations of oceanic CO2 fugacity (fCO2) evidenced a reinvigoration of the Southern Ocean carbon sink since the 2000s26,27,28. The mechanisms behind this strengthening remain a topic of active research29, making the future evolution of this critical carbon sink highly uncertain. Atmospheric changes, such as regional wind variability, have been put forward to explain this trend26,30. However, these studies also emphasize that its evolution cannot be explained by local atmospheric conditions alone. Another potential explanation is the role of an increased salinity-driven stratification of the near-surface waters26,28,31,32. While the long-term freshening of the Southern Ocean has been partially attributed to anthropogenic forcings33, the evolution of upper-ocean stratification remains difficult to predict because it may also be influenced by natural variability. Moreover, its impact on CO2 fluxes remains a fundamental open question. Paleoclimate studies have linked increased Southern Ocean stratification to reductions in atmospheric CO2. On the one hand, enhanced stratification limits deep-water upwelling and ventilation, effectively isolating the CO2-rich deep-water masses from the surface and reducing outgassing34,35,36. On the other hand, some reconstructions suggest an enhanced efficiency of the biological pump under more stratified condition37, further contributing to carbon sequestration at depth. These insights highlight the critical role that stratification may have in controlling the carbon balance of the Southern Ocean, both in the past and, possibly, in a warming future.

In this study, we present a circumpolar analysis of repeat transects of long-term carbonate biogeochemistry sampling in the Southern Ocean. Our results reveal that the potential for CO2 outgassing increased by on average 10 µatm in the subsurface (100–200 m) layer since the 1990s, with regional values ranging from 2.4 to 17 µatm. An analysis of water mass distributions for each hydrographic section reveals that the anomalies are associated with circumpolar deep water (CDW) reaching shallower depth (on average 40 m shallower), a pattern consistent with enhanced upwelling under stronger westerly winds38. However, this anomaly remains trapped at depth because of a pronounced increase in upper-ocean stratification, which acts as a barrier to vertical exchange. A long-term freshening trend since the 1980s33,39,40, confirmed in this study with a subset of data that also contains biogeochemical observations since the 1990s (Methods), has strengthened the density stratification of the upper ocean, limiting the vertical exchange of carbon. Thus, the high-CO2 signal remains isolated below the surface, temporarily stalling an increase in CO2 outgassing from the subsurface and providing an explanation for the observed strengthening of the Southern Ocean carbon sink in this period.

Circumpolar increase in subsurface fCO2 since the 1990s

Since the 1990s, the subsurface (about 100–200 m) fCO2, without the contribution of anthropogenic fCO2, has consistently increased across all seven hydrographic sections of the Southern Ocean (south of 55° S) studied (Fig. 1). We calculated fCO2 from the observed DIC, which was adjusted to only reflect changes in ocean circulation and mixing (Methods), total alkalinity (TA), salinity and temperature. It shows an average subsurface (dashed box in Fig. 1b) increase of 10.0 µatm across all sections (ranging from 2.4 µatm to 17.0 µatm) between the 1972–2013 climatology41 and the most recent sections (after 2013)42. The average subsurface fCO2 increase ranges on average from 470 to 480 µatm, remaining well above current (2025) atmospheric levels (~420 µatm), which implies that these upwelled deep waters would lead to a CO2 release at the surface.

a, Left: schematic of the effects of enhanced westerly winds. Right: enhanced stratification on the distribution of the water masses in the Southern Ocean. b,Section-averaged fCO2 anomaly (recent years minus climatology) calculated for depth layers across each section with anthropogenic carbon removed (Methods). The dashed box highlights the depth layers located in the subsurface. The inset map shows the location and names of the repeated sections analysed in this study.

Interestingly, these positive fCO2 anomalies are of similar magnitude across the seven regions, but only found within a specific subsurface layer (dashed box in Fig. 1b). The value of Dref, the depth of the interface between deep and surface waters, varies according to region; however, the consistent positive anomalies are always located between Dref − 50 m and Dref + 100 m, roughly corresponding to depths between 70 and 200 m. The consistency of these subsurface anomalies across a wide range of geographical regions suggests that they reflect a robust, large-scale, long-term change. In contrast, closer to the surface (above Dref − 50 m), the signal is more variable and the fCO2 anomalies lack a distinct pattern (Fig. 1b). The top 100 m show greater variability, probably reflecting both seasonal differences between sections (sampled from late spring to early autumn; Extended Data Table 1) and increased regional heterogeneity in surface waters during summer. Although our method focuses on subsurface dynamic processes and excludes the influence of biological activity and air–sea gas exchange, these processes may still affect the surface layers. Such processes are particularly active in summer and strongly influence carbon cycling in the upper ocean43, probably contributing to the reduced coherence of the signal observed near the surface. In this study, we did not investigate potential effects of long-term changes in biological activities and air–sea gas exchange on the observed DIC changes.

The subsurface increase in fCO2 is consistent with an intensification of the overturning circulation and suggests a higher potential for CO2 outgassing if these waters were to reach the surface. Such an increase in outgassing potential south of 55° S would reduce the efficiency of the Southern Ocean CO2 sink. However, as of the last repeat section in this dataset from the year 2019 (section I06S; Fig. 1b), surface and subsurface anomalies remain mostly decoupled. Thus, the signal remains confined below 100 m in most sections. This decoupling between the subsurface and surface layers underscores the role of stratification in isolating these anomalies and temporarily stalling their propagation to the surface.

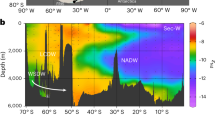

Upward displacement of deep water

The subsurface increase in fCO2 is directly linked to a change in water mass distribution over the past decades (water mass identification and fraction in Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1). In all seven sections analysed, we observed that upper CDW (uCDW), which is naturally enriched in DIC, is progressively replacing the overlaying winter water (WW) in the 100–200-m layer (Fig. 2). This shift results in a shoaling of uCDW, bringing higher DIC concentrations closer to the surface and causing a corresponding increase in fCO2.

a, Depth of the 80% uCDW layer (circles), depth of the layer where fCO2 exceeds 500 µatm (triangles) and depth of the layer where oxygen levels fall below 215 µmol kg−1 (squares) for each section presented on the map. b, Distribution of water masses along section A12 in the 1972–2013 climatology. c, Distribution of water masses along section A12 in the most recent section (December 2014). d, Changes in water mass distribution between the climatology and December 2014 section.

Each section reveals a shift in water mass properties between the 1972–2013 climatology and the recent (after 2013) measurements. The uCDW in the Atlantic sector, along the A12 section (Fig. 3), is characterized by high DIC concentrations (~2,260 µmol kg−1; Fig. 3b,d), low oxygen levels (<220 µmol kg−1) and elevated salinity and temperature. Its fCO2 is considerably higher than atmospheric levels (~570 µatm at depths greater than 500 m). In contrast, the WW is fresher (S < 34.5), colder (T < −1 °C) and contains less DIC (~2,210 µmol kg−1). It is a younger water mass, formed through deep mixing in winter44,45, resulting in higher oxygen concentrations (>300 µmol kg−1).

a, Temperature–salinity (TS) diagram for section A12 in the 1972–2013 climatology (diamonds) and the most recent section (December 2014, squares), colour-coded according to water mass fraction. The shaded areas define 100% WW and 100% uCDW (Methods, Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1). b, DIC versus TA diagram for section A12 in the 1972–2013 climatology (diamonds) and December 2014 (squares), colour-coded according to water mass fraction. c, Averaged TS values for 90% uCDW, 90% WW and the intermediate water mass (between 90% WW and 90% uCDW), colour-coded according to mean oxygen levels. The vertical and horizontal bars indicate the s.d. of the observed values, representing the variability within each water mass type. Mean and s.d. values are listed in Extended Data Table 2. d, Averaged DIC versus TA values for 90% uCDW, 90% WW and the intermediate water mass, with background fCO2. The vertical and horizontal bars indicate the s.d. of the observed values. c,d, The sample sizes used to derive the statistics are n = 20 for the WW, n = 15 for the uCDW and n = 32 for the intermediate water mass.

The recent sections since 2013 consistently show that the uCDW is reaching shallower depths compared to the 1990s (Fig. 2). The depth at which waters with fCO2 higher than 500 µatm are present is now shallower in these recent sections, matching the shallower occurrence of waters with oxygen levels below 215 µmol kg−1. On average, the depth limit below which water contains an 80% uCDW fraction has become shallower by 40 m. This shoaling ranges from 17.6 m in section 6 to 83.3 m in section 5 and explains the positive fCO2 anomalies observed at the subsurface, as carbon-rich uCDW replaces WW.

In addition to this vertical redistribution, the properties of the water masses have also evolved over time. The intermediate layer, between 90% WW and 90% uCDW, now exhibits properties more similar to uCDW, such as increased temperature and salinity, higher DIC levels, greater alkalinity and lower oxygen concentrations (for example, section A12; Fig. 3). However, this intermediate layer occupies a smaller volume, as it is progressively replaced by uCDW. Meanwhile, uCDW itself has become warmer (+0.2 °C in section A12; Fig. 3), in agreement with the current literature46,47, while WW has become colder (−0.17 °C) and fresher (−0.06). The increasing density gradient between these water masses strengthens the density stratification in the upper water column (distance between curved isopycnals in Fig. 3c). The consistent changes across all seven sections (Fig. 2a) reflect a widespread alteration in water mass composition and biogeochemistry in the Southern Ocean over recent decades.

Near-surface freshening

While the uCDW is shoaling, the WW is freshening, further differentiating its properties from the underlying deep water. The observed freshening of the WW core (up to −0.3 in Section A12, Fig. 4, with maximum anomalies across sections ranging from −0.17 to −0.37; Extended Data Fig. 2) reflects a circumpolar trend that leads to an increase in stratification and prevents the uCDW from mixing with the WW. Thus, while the uCDW moves closer to the surface, leading to positive fCO2 anomalies in the subsurface (Fig. 1), its direct exchange with the atmosphere is limited. Consequently, the freshening of the WW during this period prevented the outgassing associated with the upwelling of the uCDW.

a, Salinity anomalies between the 1972–2013 climatology and December 2014 along section A12. b, Oxygen anomalies between the 1972–2013 climatology and December 2014 along section A12. c, Map of all sections in the the Global Ocean Data Analysis Project (GLODAP) database (light grey; Methods) with repeat sections analysed in this study highlighted (dark grey).

While temperature changes in the WW vary between sections, the freshening of WW is a consistent circumpolar trend observed south of 55° S (all salinity sections shown in Extended Data Fig. 2), in agreement with previous observational and modelling studies33,39,48. This freshening affects the physical and biogeochemical characteristics of the water column: the WW is becoming less alkaline (Fig. 3d) and more oxygenated (up to −50 µmol kg−1 in section A12; Fig. 4), further increasing its biogeochemical distinction from the uCDW. Additionally, reduced WW density intensifies the stratification between WW and the shoaling uCDW. Long-term trends in uCDW, including increasing salinity and temperature (Fig. 3c), further reinforce this gradient, amplifying the contrast between these water masses.

Therefore, comparing the recent sections with the climatology reveals a salinity anomaly dipole, where the WW is fresher, and the layer below is saltier, as the WW is replaced by the uCDW (Fig. 4). While this cap currently mitigates surface outgassing, the ongoing shoaling of the uCDW and evolving properties of both water masses suggest that this balance may not persist indefinitely.

Discussion

Our findings reveal that the enhanced freshening of the surface Southern Ocean caps an increased subsurface fCO2 since the 1990s. This increase is linked to a vertical shift in water mass distribution, particularly the shoaling of uCDW. At the same time, stronger surface stratification has effectively isolated the high-CO2 uCDW from the atmosphere, temporarily preventing outgassing. However, as stratification strengthens and uCDW moves closer to the surface, the subsurface layer between 100 and 200 m is becoming warmer, more saline and richer in DIC, indicating a higher potential for CO2 outgassing if this water reaches the surface. The shoaling of uCDW and the increased subsurface fCO2 are consistent with an increased upwelling in the Southern Ocean, which is associated with stronger westerly winds in a changing climate11,12,13. Importantly, our reconstruction of the DIC from TA removes the influence of air–sea gas exchange (including intrusion of anthropogenic CO2) and biological productivity, two processes that can strongly influence the variability of the carbon cycle and are highly variable on seasonal and regional scales. This approach allowed us to isolate the role of long-term ocean circulation and mixing changes, revealing that uCDW and high-fCO2 waters are being trapped below the surface, preventing the anticipated weakening of the Southern Ocean carbon sink. This increased stratification is the key mechanism delaying the emergence of model-predicted outgassing in this region.

Our findings offer a mechanistic explanation that helps reconcile previously reported discrepancies between model projections and observational studies regarding the evolution of the Southern Ocean carbon sink. Early modelling efforts simulated a weakening of the sink because of increased upwelling driven by strengthening westerly winds11. Yet, observational studies reported a reinvigoration of the sink in the 2000s26,28. Meanwhile, more recent estimates, using biogeochemical Argo floats, revealed unexpected wintertime CO2 outgassing10,49, emphasizing the central role of subsurface carbon-rich waters in driving seasonal variability. Our study shows that this upwelling of carbon-rich waters has indeed strengthened over the past decades, but that the expected weakening of the sink has probably been delayed. The reason for this delay is a freshening-driven increased stratification, which is trapping high-DIC waters in the subsurface. These results suggest that models may underestimate the strength and persistence of surface stratification, which affects CO2 release from subsurface sources. By identifying the physical mechanisms behind this vertical decoupling, we provide a new framework for understanding current trends and for better anticipating future transitions in the ocean carbon sink.

As shown in prior studies33,48 and supported in this study, the stratification of the Southern Ocean has been increasing because of a circumpolar decrease of surface salinity for several decades. This freshening is the result of an increased precipitation over evaporation in this region50, an enhanced northward export of sea ice51 and, possibly, an increased export of glacial meltwater from the continental shelf39,52. The influence of an increased SAM on Southern Ocean freshening on decadal to multi-decadal timescales still remains uncertain53,54. While anthropogenic forcing contributes to this freshening33, it is difficult to predict the variability of the surface stratification of the Southern Ocean. In 2016, a strong change in sea-ice regime was observed55, as the period of growing sea-ice cover suddenly came to an end; low sea-ice extent years have been observed since then. This transition coincides with a recent reversal in surface salinity trends (from freshening to salinification), which has weakened upper-ocean stratification across the circumpolar Southern Ocean56. One proposed mechanism is increased upward mixing of relatively warm and salty uCDW57; however, changes in sea-ice formation and melt could also have affected changes in upper-ocean salinity. The increased surface salinity suggests a possible transition towards a less stratified upper ocean, which may have implications for CO2 ventilation. The biogeochemical implication of this transition could be elevated CO2 outgassing, as suggested by our results and in agreement with prior studies suggesting a weakening of the Southern Ocean carbon sink. CO2 would accumulate more at the surface of the ocean and, ultimately, the atmosphere, thus accelerating global warming. However, because of the limited amount of carbonate data after 2016, the biogeochemical impact of this shift remains uncertain.

This study relies on a limited number of repeated hydrographic sections, most of which were sampled during the summer months, which limits our ability to assess changes in surface air–sea CO2 fluxes. Wintertime sections would be particularly valuable for resolving carbon dynamics in the upper ocean and validating stratification-driven suppression of surface outgassing. While recent studies56 suggested profound changes in both surface and subsurface properties, further occupations of these hydrographic lines will be required to determine whether these changes represent sustained trends on biogeochemical parameters. Additionally, the spatial and temporal sparsity of carbonate system data limits our capacity to conduct formal attribution analyses. Nevertheless, the biogeochemical changes we observed (namely, enhanced upper-ocean stratification, freshening and the shoaling of CO2-rich uCDW) are consistent with mechanisms identified in modelling and observational studies attributing these shifts to anthropogenic forcing, including greenhouse gas emissions and stratospheric ozone depletion18,33. At the same time, internal variability in atmospheric and oceanic circulation (for example, shifts in the SAM) could also contribute to the observed patterns. Given the observational gaps, particularly in time series and winter coverage, we cannot fully disentangle the respective roles of natural variability and long-term forced trends in the upper 100 m of the ocean. This underscores the urgent need for sustained year-round observations to refine attribution and improve projections of the Southern Ocean carbon sink.

Our results align with paleoclimate studies, which suggest that lower atmospheric CO2 levels are expected when deep-water masses are isolated from the atmosphere34,35. This agreement highlights the importance of stratification changes in controlling carbon cycling in the Southern Ocean. Further research is essential to fully understand the mechanisms and feedbacks at play and to predict how ongoing climate change might alter this balance. By isolating the subsurface signal arising from ocean circulation changes, we provide evidence of how changes in ocean dynamics and stratification can both mask and drive considerable shifts in the ocean’s carbon cycle, having important consequences on the evolution of the Southern Ocean carbon sink with climate change.

Methods

Long-term biogeochemical anomalies

This study is based on the analysis of two versions of the GLODAP database. The 2023 v.2 of the data product42 entails 1,108 cruises with quality-controlled biogeochemical measurements covering the global ocean from 1972 to 2021. For the Southern Ocean, we identified sections that were sampled at least twice between 1972 and 2013, and with at least one additional sampling after 2013 (except for section S04I in 2013). The cruises after 2013 are referred to as ‘most recent cruises’ (Extended Data Table 1), and data were vertically linearly interpolated over 33 depth levels for homogeneity with the climatology. They were then compared to the climatology in the second version of the GLODAPv2 database41 that we used in this study, by selecting the closest grid point of the climatology for each vertical profile and taking the difference, which results in the computed anomalies. The 1972 to 2013 climatology is published on a 1° × 1° grid and on 33 depth levels. The climatology along the sections identified is representative of an average over the 1980s to 2000s as several cruises were conducted during this time. For simplicity, we refer to the climatology period as the ‘1990s’ throughout the article. Therefore, the salinity, temperature, oxygen, DIC and TA anomalies are the difference between the 1972–2013 climatology extracted along the identified repeated sections and the sections after 2013. Physical parameters such as salinity and temperature from GLODAP were used to ensure the accuracy of the comparison between physical and biogeochemical parameters, as recommended by the database guidelines41.

Water mass identification

Because of the local water mass properties of the regions in which each section is located, water masses are defined from the TS diagram (Fig. 3a) of each section (Extended Data Table 1). WW is located at the respective temperature and salinity minimum of the diagram (blue-shaded area in Fig. 3a). The core of the uCDW is located at the local temperature and salinity maximum (purple-shaded area in Fig. 3a); deeper points than this subsurface temperature maximum are not considered in the analysis. The TS thresholds defining the water masses are identified from the climatological values. They constitute the 100% WW and uCDW, respectively. To assess the water mass fraction, we orthogonally projected the TS diagram points onto the WW-uCDW mixing line. Data points with distances (H; Extended Data Fig. 2) in TS space greater than 0.25 from the mixing line are excluded from the analysis because they probably reflect mixing between surface waters and uCDW rather than the target water masses. This threshold value is consistently applied across all sections analysed in this study. Changing this value does not change the result significantly as long as not too many points from the surface waters are included in the analysis.

DIC from circulation

DIC anomalies are strongly affected by the anthropogenic increase of CO2 in the ocean. In this study, the focus is on the impact of long-term changes in circulation patterns on water mass properties that are related to exchanges between subsurface and deep-water masses, but not with the atmosphere. To isolate the DIC changes driven by ocean circulation, we estimated the DIC contribution resulting from mixing between WW and uCDW (DICm). We used TA, a measure of the ocean’s capacity to buffer acidification, as a conservative tracer as it is not affected by gas exchange and is minimally affected by biological processes (photosynthesis and respiration). In particular, the region south of the Polar Front is dominated by the production of heavily silicified diatoms (a phenomenon often referred to as the ‘silicate trap’); therefore, it is not prone to large-scale blooms of calcifying phytoplankton that would alter TA through calcium carbonate production or dissolution58. Any such biological influence on TA, and thus on DICₘ, is expected to be small in the subsurface layers studied here. Nevertheless, this assumption introduces some uncertainty and should be kept in mind when interpreting DICₘ estimates.

We assume that the changes in TA (\(\Delta {\rm{T}}{\rm{A}}\)) between the climatology and the recent section can be approximated by the climatological TA of the uCDW (\({{\rm{T}}{\rm{A}}}_{{\rm{u}}{\rm{C}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{W}}{\rm{c}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{m}}}\)) multiplied by a mixing ratio (\({M}_{{\rm{r}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{o}}}\)), as mixing with uCDW is the main source of change in TA. In this context, the mixing ratio represents the proportion of uCDW to a given water sample; therefore, it can be computed as \({M}_{{\rm{r}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{o}}}=\Delta {{\rm{T}}{\rm{A}}/{\rm{T}}{\rm{A}}}_{{\rm{u}}{\rm{C}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{W}}{\rm{c}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{m}}}\). The associated change in DIC due to mixing (ΔDICm) is then computed as \(\Delta {{\rm{D}}{\rm{I}}{{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{m}}}={\rm{D}}{\rm{I}}{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{u}}{\rm{C}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{W}}{\rm{c}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{m}}}\times {M}_{{\rm{r}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{o}}}\) and the DIC resulting from circulation (DICm) is \({\rm{D}}{\rm{I}}{{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{m}}}={{\rm{D}}{\rm{I}}{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{c}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{m}}}+\Delta {\rm{D}}{\rm{I}}{{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\).

Subsurface fCO2

fCO2 represents the effective pressure of CO2 in seawater and is used as a more accurate measure than the partial pressure of CO2 for describing gas exchange with the atmosphere for non-ideal behaviour gases. In the subsurface, it is derived with the MATLAB CO2SYS v.3.159 software from TA and DICm. We used potential temperature and surface pressure to compute a potential fCO2, meaning the fCO2 values that the water parcel would obtain if it was brought up to the surface. The nutrients required for the fCO2 calculation are provided by the GLODAP database; dissociation constants were taken as those of Lueker et al.60.

Data availability

The biogeochemical data from the GLODAP database41,42 are publicly available at https://glodap.info/index.php/merged-and-adjusted-data-product-v2-2023/; the climatology data are available at https://glodap.info/index.php/mapped-data-product/.

Code availability

The key codes needed to reproduce the results are available via Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16873426 (ref. 61). The Matlab codes for CO2SYS are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4023039 (ref. 59).

References

Sabine, C. L. et al. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Science 305, 367–371 (2004).

Gruber, N. et al. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science 363, 1193–1199 (2019).

Frölicher, T. L. et al. Dominance of the Southern Ocean in anthropogenic carbon and heat uptake in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 28, 862–886 (2015).

Caldeira, K. & Duffy, P. B. The role of the Southern Ocean in uptake and storage of anthropogenic carbon dioxide. Science 287, 620–622 (2000).

Morrison, A. K., Waugh, D. W., Hogg, A. M., Jones, D. C. & Abernathey, R. P. Ventilation of the Southern Ocean pycnocline. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 14, 405–430 (2022).

Marshall, J. & Speer, K. Closure of the meridional overturning circulation through Southern Ocean upwelling. Nat. Geosci. 5, 171–180 (2012).

Talley, L. Closure of the global overturning circulation through the Indian, Pacific, and Southern Oceans: schematics and transports. Oceanography 26, 80–97 (2013).

Murnane, R. J., Sarmiento, J. L. & Le Quéré, C. Spatial distribution of air-sea CO2 fluxes and the interhemispheric transport of carbon by the oceans. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 13, 287–305 (1999).

Chen, H., Haumann, F. A., Talley, L. D., Johnson, K. S. & Sarmiento, J. L. The deep ocean’s carbon exhaust. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 36, e2021GB007156 (2022).

Bushinsky, S. M. et al. Reassessing Southern Ocean air-sea CO2 flux estimates with the addition of biogeochemical float observations. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 1370–1388 (2019).

Le Quéré, C. et al. Saturation of the Southern Ocean CO2 sink due to recent climate change. Science 316, 1735–1738 (2007).

Lovenduski, N. S., Gruber, N. & Doney, S. C. Toward a mechanistic understanding of the decadal trends in the Southern Ocean carbon sink. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB003139 (2008).

Waugh, D. W., Primeau, F., DeVries, T. & Holzer, M. Recent changes in the ventilation of the southern oceans. Science 339, 568–570 (2013).

Miller, R. L., Schmidt, G. A. & Shindell, D. T. Forced annular variations in the 20th century Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment Report models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 111, D18101 (2006).

Gillett, N. P. & Thompson, D. W. J. Simulation of recent Southern Hemisphere climate change. Science 302, 273–275 (2003).

Marshall, G. J. Trends in the southern annular mode from observations and reanalyses. J. Clim. 16, 4134–4143 (2003).

Thompson, D. W. J. et al. Signatures of the Antarctic ozone hole in Southern Hemisphere surface climate change. Nat. Geosci. 4, 741–749 (2011).

Lee, S.-K. et al. Human-induced changes in the global meridional overturning circulation are emerging from the Southern Ocean. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 69 (2023).

Bronselaer, B. et al. Importance of wind and meltwater for observed chemical and physical changes in the Southern Ocean. Nat. Geosci. 13, 35–42 (2020).

Lovenduski, N. S., Gruber, N., Doney, S. C. & Lima, I. D. Enhanced CO2 outgassing in the Southern Ocean from a positive phase of the Southern Annular Mode. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GB002900 (2007).

Lenton, A. & Matear, R. J. Role of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) in Southern Ocean CO2 uptake. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GB002714 (2007).

Lenton, A. et al. Sea–air CO2 fluxes in the Southern Ocean for the period 1990–2009. Biogeosciences 10, 4037–4054 (2013).

Metzl, N. Decadal increase of oceanic carbon dioxide in Southern Indian Ocean surface waters (1991–2007). Deep-Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 607–619 (2009).

Zheng, F., Li, J., Clark, R. T. & Nnamchi, H. C. Simulation and projection of the Southern Hemisphere annular mode in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 26, 9860–9879 (2013).

Goyal, R., Sen Gupta, A., Jucker, M. & England, M. H. Historical and projected changes in the Southern Hemisphere surface westerlies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090849 (2021).

Landschützer, P. et al. The reinvigoration of the Southern Ocean carbon sink. Science 349, 1221–1224 (2015).

Gregor, L., Kok, S. & Monteiro, P. M. S. Interannual drivers of the seasonal cycle of CO2 in the Southern Ocean. Biogeosciences 15, 2361–2378 (2018).

Munro, D. R. et al. Recent evidence for a strengthening CO2 sink in the Southern Ocean from carbonate system measurements in the Drake Passage (2002–2015). Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7623–7630 (2015).

Gruber, N., Landschützer, P. & Lovenduski, N. S. The variable Southern Ocean carbon sink. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 11, 159–186 (2019).

Keppler, L. & Landschützer, P. Regional wind variability modulates the Southern Ocean carbon sink. Sci. Rep. 9, 7384 (2019).

Lovenduski, N. S. & Ito, T. The future evolution of the Southern Ocean CO2 sink. J. Mar. Res. 67, 597–617 (2009).

Terhaar, J., Frölicher, T. L. & Joos, F. Southern Ocean anthropogenic carbon sink constrained by sea surface salinity. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd5964 (2021).

Swart, N. C., Gille, S. T., Fyfe, J. C. & Gillett, N. P. Recent Southern Ocean warming and freshening driven by greenhouse gas emissions and ozone depletion. Nat. Geosci. 11, 836–841 (2018).

François, R. et al. Contribution of Southern Ocean surface-water stratification to low atmospheric CO2 concentrations during the last glacial period. Nature 389, 929–935 (1997).

Anderson, R. F. et al. Wind-driven upwelling in the Southern Ocean and the deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2. Science 323, 1443–1448 (2009).

Hasenfratz, A. P. et al. The residence time of Southern Ocean surface waters and the 100,000-year ice age cycle. Science 363, 1080–1084 (2019).

Anderson, R. F., Chase, Z., Fleisher, M. Q. & Sachs, J. The Southern Ocean’s biological pump during the Last Glacial Maximum. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 49, 1909–1938 (2002).

Hogg, A. M., Spence, P., Saenko, O. A. & Downes, S. M. The energetics of Southern Ocean upwelling. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 47, 135–153 (2017).

Haumann, F. A., Gruber, N. & Münnich, M. Sea-ice induced Southern Ocean subsurface warming and surface cooling in a warming climate. AGU Adv. 1, e2019AV000132 (2020).

IPCC IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Lauvset, S. K. et al. A new global interior ocean mapped climatology: the 1° × 1° GLODAP version 2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 325–340 (2016).

Lauvset, S. K. et al. The annual update GLODAPv2.2023: the global interior ocean biogeochemical data product. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 2047–2072 (2024).

Hauck, J. et al. The Southern Ocean carbon cycle 1985–2018: mean, seasonal cycle, trends, and storage. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2023GB007848 (2023).

Toole, J. M. Sea ice, winter convection, and the temperature minimum layer in the Southern Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 86, 8037–8047 (1981).

Spira, T., Swart, S., Giddy, I. & du Plessis, M. The observed spatiotemporal variability of Antarctic winter water. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 129, e2024JC021017 (2024).

Zu, Y., Gao, L., Guo, G. & Fang, Y. Changes of circumpolar deep water between 2006 and 2020 in the south-west Indian Ocean, East Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 197, 105043 (2022).

Schmidtko, S., Heywood, K. J., Thompson, A. F. & Aoki, S. Multidecadal warming of Antarctic waters. Science 346, 1227–1231 (2014).

Sallée, J.-B. et al. Summertime increases in upper-ocean stratification and mixed-layer depth. Nature 591, 592–598 (2021).

Gray, A. R. et al. Autonomous biogeochemical floats detect significant carbon dioxide outgassing in the high-latitude Southern Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 9049–9057 (2018).

Akhoudas, C. H. et al. Isotopic evidence for an intensified hydrological cycle in the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean. Nat. Commun. 14, 2763 (2023).

Haumann, F. A., Gruber, N., Münnich, M., Frenger, I. & Kern, S. Sea-ice transport driving Southern Ocean salinity and its recent trends. Nature 537, 89–92 (2016).

Roach, L. A. et al. Winds and meltwater together lead to Southern Ocean surface cooling and sea ice expansion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105948 (2023).

Ferreira, D., Marshall, J., Bitz, C. M., Solomon, S. & Plumb, A. Antarctic Ocean and sea ice response to ozone depletion: a two-time-scale problem. J. Clim. 28, 1206–1226 (2015).

Kostov, Y., Ferreira, D., Armour, K. C. & Marshall, J. Contributions of greenhouse gas forcing and the Southern Annular Mode to historical Southern Ocean surface temperature trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1086–1097 (2018).

Purich, A. & Doddridge, E. W. Record low Antarctic sea ice coverage indicates a new sea ice state. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 314 (2023).

Silvano, A. et al. Rising surface salinity and declining sea ice: a new Southern Ocean state revealed by satellites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2500440122 (2025).

Spira, T. et al. Wind-triggered Antarctic sea ice decline preconditioned by thinning winter water. Preprint at Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5919587/v1 (2025).

Krumhardt, K. M., Long, M. C., Lindsay, K. & Levy, M. N. Southern Ocean calcification controls the global distribution of alkalinity. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2020GB006727 (2020).

Sharp, J. D. et al. CO2SYSv3 for MATLAB. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4023039 (2020).

Lueker, T. J., Dickson, A. G. & Keeling, C. D. Ocean pCO2 calculated from dissolved inorganic carbon, alkalinity, and equations for K1 and K2: validation based on laboratory measurements of CO2 in gas and seawater at equilibrium. Mar. Chem. 70, 105–119 (2000).

Olivier, L. & Haumann, F. A. Scripts for the publication “Southern Ocean freshening stalls deep ocean CO2 release in a changing climate”. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16873426 (2025).

Acknowledgements

L.O. is supported by the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association (no. VH-NG-19-33). F.A.H. is supported by the European Union (European Research Council, VERTEXSO (VERTical EXchange in the Southern Ocean), no. 101041743) and the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association (no. VH-NG-19-33). We acknowledge the efforts of the GLODAP community in producing a uniformly calibrated and quality-controlled dataset of carbonate system and other biogeochemical variables. In part, data were collected and made publicly available by the International Global Ship-based Hydrographic Investigations Program (http://www.go-ship.org/) and the national programmes that contribute to it. We also acknowledge early data collection as part of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment and all other data collectors and contributors who have maintained the Southern Ocean sections for many decades, as well as the associated reference and best practice groups for their invaluable work. We thank M. Hoppema and O. Boebel for maintaining the Prime Meridian section as part of the Hybrid Antarctic Float Observing System, for the associated data collection and for their advice. We acknowledge support from the Open Access publication fund of the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung (AWI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.O. and F.A.H. conceptualized the study. L.O. wrote the paper with substantial input from F.A.H. Both authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and reviewed the paper. Funding for this project was acquired by F.A.H.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Laique Djeutchouang and Precious Mongwe for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Water mass fraction.

Temperature-salinity diagram for section A12. The core of the Winter Water and upper Circumpolar Deep Water is indicated by the dot. H indicates the distance from the WW-uCDW mixing line.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Salinity anomalies.

Salinity anomalies between the 1972-2013 climatology and the post-2013 sections.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olivier, L., Haumann, F.A. Southern Ocean freshening stalls deep ocean CO2 release in a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 1219–1225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02446-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02446-3