Abstract

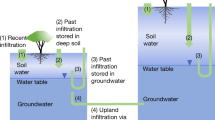

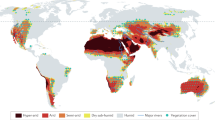

Water is indispensable for life on Earth. Plants use water either from recent precipitation (within a month) or from past precipitation stored in deeper soil (PP; at least a month ago) to maintain metabolism and growth. It is widely known that plants tend to rely more on PP to buffer against short-term rainfall deficits. However, how this reliance has changed in response to global change remains unclear. Here we develop a novel framework to estimate temporal changes in plant reliance on PP during the past four decades. Observational data reveal that 42% of tropical and subtropical natural ecosystems have experienced a significant increase in plant reliance on PP over the period 1982–2021 (P < 0.05). Such an increase is consistent with greening during the late growing season in drylands and drying during the wet-to-dry transitional period in non-drylands, when short-term precipitation fails to meet plant water demand. Adaptive changes in root depth and species composition may further facilitate this change in PP reliance, especially in drylands. Our study highlights the importance of PP in ecosystem functioning and implies an increasing ecosystem resilience to climate variability.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

GLEAM v3.8 can be requested from the GLEAM team (info@gleam.eu), GLEAM4 is available at https://www.gleam.eu/, the X-BASE data are available at https://doi.org/10.18160/5NZG-JMJE, the GLDAS-Noah data are available at https://doi.org/10.5067/9SQ1B3ZXP2C5, the in situ transpiration data are available from J. Nelson (jnelson@bgc-jena.mpg.de) upon reasonable request, the TRENDYv6 data are available from S. Sitch (s.a.sitch@exeter.ac.uk) upon reasonable request, both the isotope-based and the inverse modelling-based estimates are available at http://thredds-gfnl.usc.es/thredds/catalog/DATA_TRANSPSOURCES/catalog.html, the MSWEP precipitation is available at www.gloh2o.org, the CRU climate dataset is available at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/, the GPCC precipitation data are available at https://www.dwd.de/EN/ourservices/gpcc/gpcc.html, the PKU GIMMS NDVI dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8253971 (ref. 96), the ISLSCP II MODIS IGBP Land Cover is available at http://daac.ornl.gov, the tree cover data are available at https://doi.org/10.5067/MEASURES/VCF/VCF5KYR.001, the cropland area in 2019 is available at https://glad.umd.edu/dataset/croplands, the Global-AI_PET_v3 is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7504448.v5 (ref. 97), documented cases of woody encroachment are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3601454 (ref. 98) and the reconstructed TWSA are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7670849 (ref. 99). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Data analysis was performed in R 4.4.1 and Python 3.9.7, and all the figures were generated using R 4.1.1. All code used in the study is available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30919049 (ref. 100).

References

Jasechko, S. et al. Terrestrial water fluxes dominated by transpiration. Nature 496, 347–350 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. Evapotranspiration on a greening Earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 626–641 (2023).

Forzieri, G. et al. Increased control of vegetation on global terrestrial energy fluxes. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 356–362 (2020).

Smith, C., Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Tropical deforestation causes large reductions in observed precipitation. Nature 615, 270–275 (2023).

Spracklen, D. V., Arnold, S. R. & Taylor, C. M. Observations of increased tropical rainfall preceded by air passage over forests. Nature 489, 282–285 (2012).

Wright, J. S. et al. Rainforest-initiated wet season onset over the southern Amazon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 114, 8481–8486 (2017).

Chen, Z., Wang, W., Cescatti, A. & Forzieri, G. Climate-driven vegetation greening further reduces water availability in drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 1628–1647 (2023).

Ukkola, A. M. et al. Reduced streamflow in water-stressed climates consistent with CO2 effects on vegetation. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 75–78 (2016).

Zhao, M. et al. Ecological restoration impact on total terrestrial water storage. Nat. Sustain. 4, 56–62 (2021).

Liu, K., Li, X., Wang, S. & Zhou, G. Past and future adverse response of terrestrial water storages to increased vegetation growth in drylands. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 113 (2023).

Huxman, T. E. et al. Convergence across biomes to a common rain-use efficiency. Nature 429, 651–654 (2004).

Wang, L. et al. Dryland productivity under a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 981–994 (2022).

Jiao, W. et al. Observed increasing water constraint on vegetation growth over the last three decades. Nat. Commun. 12, 3777 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. Rising ecosystem water demand exacerbates the lengthening of tropical dry seasons. Nat. Commun. 13, 4093 (2022).

Feldman, A. F. et al. Large global-scale vegetation sensitivity to daily rainfall variability. Nature 636, 380–384 (2024).

Smith, T. & Boers, N. Global vegetation resilience linked to water availability and variability. Nat. Commun. 14, 498 (2023).

Miguez-Macho, G. & Fan, Y. Spatiotemporal origin of soil water taken up by vegetation. Nature 598, 624–628 (2021).

Bachofen, C. et al. Tree water uptake patterns across the globe. New Phytol. 242, 1891–1910 (2024).

Feldman, A. F. et al. Remotely sensed soil moisture can capture dynamics relevant to plant water uptake. Water Resour. Res. 59, e2022WR033814 (2023).

Jobbágy, E. G. & Jackson, R. B. The distribution of soil nutrients with depth: global patterns and the imprint of plants. Biogeochemistry 53, 51–77 (2001).

Lynch, J. P. in Nutrient Acquisition by Plants Vol. 181 (ed. BassiriRad, H.) Ch. 7 (Springer, 2005).

Lee, J.-E., Oliveira, R. S., Dawson, T. E. & Fung, I. Root functioning modifies seasonal climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 17576–17581 (2005).

Nepstad, D. et al. The role of deep roots in the hydrological and carbon cycles of Amazonian forests and pastures. Nature 372, 666–669 (1994).

Shi, P., Gai, H., Liu, W. & Li, Z. Links of apple tree water uptake strategies with precipitation and soil water dynamics in the deep loess deposits. J. Hydrol. 623, 129829 (2023).

Stocker, B. D. et al. Global patterns of water storage in the rooting zones of vegetation. Nat. Geosci. 16, 250–256 (2023).

Brunn, M. et al. Carbon allocation to root exudates is maintained in mature temperate tree species under drought. New Phytol. 235, 965–977 (2022).

Rowland, L., Ramírez-Valiente, J.-A., Hartley, I. P. & Mencuccini, M. How woody plants adjust above- and below-ground traits in response to sustained drought. New Phytol. 239, 1173–1189 (2023).

Eziz, A. et al. Drought effect on plant biomass allocation: a meta-analysis. Ecol. Evol. 7, 11002–11010 (2017).

Gessler, A. et al. Drought reduces water uptake in beech from the drying topsoil, but no compensatory uptake occurs from deeper soil layers. New Phytol. 233, 194–206 (2022).

Werner, C. et al. Ecosystem fluxes during drought and recovery in an experimental forest. Science 374, 1514–1518 (2021).

Yin, D. et al. Increasing deep soil water uptake during drought does not indicate higher drought resistance. J. Hydrol. 630, 130694 (2024).

Maxwell, R. M. & Condon, L. E. Connections between groundwater flow and transpiration partitioning. Science 353, 377–380 (2016).

Nelson, J. A. et al. Ecosystem transpiration and evaporation: insights from three water flux partitioning methods across FLUXNET sites. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 6916–6930 (2020).

Martens, B. et al. GLEAM v3: satellite-based land evaporation and root-zone soil moisture. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 1903–1925 (2017).

Miralles, D. G. et al. GLEAM4: global land evaporation and soil moisture dataset at 0.1° resolution from 1980 to near present. Sci. Data 12, 416 (2025).

Nelson, J. A. et al. X-BASE: the first terrestrial carbon and water flux products from an extended data-driven scaling framework, FLUXCOM-X. Biogeosciences 21, 5079–5115 (2024).

Sitch, S. et al. Recent trends and drivers of regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Biogeosciences 12, 653–679 (2015).

Rodell, M. et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 85, 381–394 (2004).

Aragão, L. E. O. C. The rainforest’s water pump. Nature 489, 217–218 (2012).

Metz, E.-M. et al. Soil respiration-driven CO2 pulses dominate Australia’s flux variability. Science 379, 1332–1335 (2023).

Zeng, N., Mariotti, A. & Wetzel, P. Terrestrial mechanisms of interannual CO2 variability. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19, GB1016 (2005).

Scott, R. The water use of two dominant vegetation communities in a semiarid riparian ecosystem. Agric. For. Meteorol. 105, 241–256 (2000).

Scott, R. L. et al. Multiyear riparian evapotranspiration and groundwater use for a semiarid watershed. J. Arid Environ. 72, 1232–1246 (2008).

Humphrey, V. & Gudmundsson, L. GRACE-REC: a reconstruction of climate-driven water storage changes over the last century. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1153–1170 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Amazon forest biogeography predicts resilience and vulnerability to drought. Nature 631, 111–117 (2024).

Moreno-Gutiérrez, C., Dawson, T. E., Nicolás, E. & Querejeta, J. I. Isotopes reveal contrasting water use strategies among coexisting plant species in a mediterranean ecosystem. New Phytol. 196, 489–496 (2012).

Currier, C. M. & Sala, O. E. Precipitation versus temperature as phenology controls in drylands. Ecology 103, e3793 (2022).

Tian, F. et al. Coupling of ecosystem-scale plant water storage and leaf phenology observed by satellite. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1428–1435 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Leaf development and demography explain photosynthetic seasonality in Amazon evergreen forests. Science 351, 972–976 (2016).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. The Community Land Model Version 5: description of new features, benchmarking, and impact of forcing uncertainty. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 4245–4287 (2019).

Medlyn, B. E. et al. Using ecosystem experiments to improve vegetation models. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 528–534 (2015).

Piao, S. et al. Plant phenology and global climate change: current progresses and challenges. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 1922–1940 (2019).

Smith, W. K. et al. Remote sensing of dryland ecosystem structure and function: progress, challenges, and opportunities. Remote Sens. Environ. 233, 111401 (2019).

Piao, S. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 1–14 (2019).

Huo, X. et al. Higher sensitivity of deep soil root productivity to precipitation changes. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 34, e70121 (2025).

Guswa, A. J. The influence of climate on root depth: a carbon cost–benefit analysis. Water Resour. Res. 44, 2007WR006384 (2008).

Gao, H. et al. Root zone in the Earth system. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 4477–4499 (2024).

Feldman, A. F. et al. Plant responses to changing rainfall frequency and intensity. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 276–294 (2024).

Lauenroth, W. K. & Bradford, J. B. Ecohydrology of dry regions of the United States: water balance consequences of small precipitation events. Ecohydrology 5, 46–53 (2012).

Huxman, T. E. et al. Precipitation pulses and carbon fluxes in semiarid and arid ecosystems. Oecologia 141, 254–268 (2004).

Lemordant, L., Gentine, P., Swann, A. S., Cook, B. I. & Scheff, J. Critical impact of vegetation physiology on the continental hydrologic cycle in response to increasing CO2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4093–4098 (2018).

Wang, L., Kaseke, K. F. & Seely, M. K. Effects of non-rainfall water inputs on ecosystem functions. WIREs Water 4, e1179 (2017).

Oki, T. & Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313, 1068–1072 (2006).

Carroll, R. W. H. et al. Declining groundwater storage expected to amplify mountain streamflow reductions in a warmer world. Nat. Water 2, 419–433 (2024).

Feng, X. et al. Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1019–1022 (2016).

Mastrotheodoros, T. et al. More green and less blue water in the Alps during warmer summers. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 155–161 (2020).

Pokhrel, Y. et al. Global terrestrial water storage and drought severity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 226–233 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. Water budgets control the resilience of large-scale ecological restoration. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL116914 (2025).

Ryan, C. M., Williams, M., Grace, J., Woollen, E. & Lehmann, C. E. R. Pre-rain green-up is ubiquitous across southern tropical Africa: implications for temporal niche separation and model representation. New Phytol. 213, 625–633 (2017).

Zhao, M., Aa, G., Liu, Y. & Konings, A. Evapotranspiration frequently increases during droughts. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1024–1030 (2022).

Miralles, D. G. et al. Global land-surface evaporation estimated from satellite-based observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 453–469 (2011).

Penman, H. L. Natural evaporation from open water, bare soil and grass. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 193, 120–145 (1948).

Koppa, A., Rains, D., Hulsman, P., Poyatos, R. & Miralles, D. G. A deep learning-based hybrid model of global terrestrial evaporation. Nat. Commun. 13, 1912 (2022).

Miralles, D. G., Gash, J. H., Holmes, T. R. H., De Jeu, R. A. M. & Dolman, A. J. Global canopy interception from satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, 2009JD013530 (2010).

Liu, Y. Y., De Jeu, R. A. M., McCabe, M. F., Evans, J. P. & Van Dijk, A. I. J. M. Global long-term passive microwave satellite-based retrievals of vegetation optical depth. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L18402 (2011).

Hansen, M. & Song, X.-P. Vegetation Continuous Fields (VCF) Yearly Global 0.05 Deg. NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/measures/vcf/vcf5kyr.001 (2018).

Beck, H. E. et al. MSWEP V2 global 3-hourly 0.1° precipitation: methodology and quantitative assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 473–500 (2019).

Humphrey, V., Rodell, M. & Eicker, A. Using satellite-based terrestrial water storage data: a review. Surv. Geophys. 44, 1489–1517 (2023).

Zhou, S., Yu, B., Zhang, Y., Huang, Y. & Wang, G. Partitioning evapotranspiration based on the concept of underlying water use efficiency. Water Resour. Res. 52, 1160–1175 (2016).

Pastorello, G. et al. The FLUXNET2015 dataset and the ONEFlux processing pipeline for eddy covariance data. Sci. Data 7, 225 (2020).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7, 109 (2020).

Zomer, R. J., Xu, J. & Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database. Sci. Data 9, 409 (2022).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC full data reanalysis v.7.0: monthly land-surface precipitation from rain gauges built on GTS based and historic data. NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research https://doi.org/10.5065/D6000072 (2016).

Friedl, M. A. et al. ISLSCP II MODIS (collection 4) IGBP land cover, 2000–2001 (v.1). ORNL Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/968 (2010).

Potapov, P. et al. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food 3, 19–28 (2021).

García Criado, M., Myers-Smith, I. H., Bjorkman, A. D., Lehmann, C. E. R. & Stevens, N. Woody plant encroachment intensifies under climate change across tundra and savanna biomes. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 925–943 (2020).

Li, M. et al. Spatiotemporally consistent global dataset of the GIMMS Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (PKU GIMMS NDVI) from 1982 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 4181–4203 (2023).

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 15, 259–263 (2006).

Good, S. P., Moore, G. W. & Miralles, D. G. A mesic maximum in biological water use demarcates biome sensitivity to aridity shifts. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1883–1888 (2017).

Porporato, A., Daly, E. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Soil water balance and ecosystem response to climate change. Am. Nat. 164, 625–632 (2004).

Rossi, B. Advances in Forecasting Under Instability. Economic Research Initiatives at Duke (ERID) Working Paper No. 111 https://ssrn.com/abstract=1934348 (2012).

Liu, Y., Kumar, M., Katul, G. G. & Porporato, A. Reduced resilience as an early warning signal of forest mortality. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 880–885 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Increasing sensitivity of dryland vegetation greenness to precipitation due to rising atmospheric CO2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4875 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Keenan, T. F. & Zhou, S. Exacerbated drought impacts on global ecosystems due to structural overshoot. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1490–1498 (2021).

Rohde, M. M. et al. Establishing ecological thresholds and targets for groundwater management. Nat. Water 2, 312–323 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Spatiotemporally consistent global dataset of the GIMMS Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (PKU GIMMS NDVI) from 1982 to 2022 (v.1.2). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8253971 (2023).

Trabucco, A. & Zomer, R. Global aridity index and potential evapotranspiration (ET0) database v.3. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7504448.v5 (2019).

Criado, M. G. marianagarciacriado/WoodyEncroachmentHub: first release of WoodyEncroachmentHub (v.1.0.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3601454 (2020).

Humphrey, V. & Gudmundsson, L. GRACE-REC: a reconstruction of climate-driven water storage changes over the last century. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7670849.v3 (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. Increase in plant reliance on past precipitation associated with greening and drying. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30919049 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42141005). D.G.M. acknowledges support from the European Research Council Consolidator Grant HEAT (101088405). X.T. acknowledges support from the US National Science Foundation grants 2442269 and 2106030. H.Y. acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42401104). This work is supported by the High-Performance Computing Platform of Peking University. We thank the TRENDY v12 project for providing model simulations to support our analysis. We appreciate J. Nelson for providing the transpiration estimates at flux tower sites.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. conceived the idea, Y.Z. and H.Z. designed the study, H.Z. performed the analysis, and Y.Z. and H.Z. wrote the first draft of the paper. All co-authors commented on the results and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Ying Fan, Taylor Smith and Yuting Yang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Spatial patterns of monthly \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{{{\bf{P}}}_{{\bf{P}}}}\).

Spatial patterns of \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\) in January (a), February (b), March (c), April (d), May (e), June (f), July (g), August (h), September (i), October (j), November (k), and December (l) during 2001–2015.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Temporal dynamics of monthly \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{{{\bf{P}}}_{{\bf{P}}}}\), PR, and EP.

Average monthly \({\beta }_{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{P}}}\), PR, and EP across Köppen–Geiger climate types (a‒i). Brown hollow squares, red lines, and blue bars represent \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\), \({E}_{P}\), and \({P}_{R}\), respectively, across 9 major climate types during 2001–2015. Brown error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation of \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\) within each climate regions. Data for the Southern Hemisphere are shifted by six months. The proportional area covered by each major climate type in the study regions is annotated above the corresponding subplot.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Seasonal changes of PR −EP and NDVI.

Monthly \({P}_{R}-{E}_{P}\) and NDVI during 1982 − 2021 in the two-dimensional space, with the reordered months of the year as x-axis and aridity index as y-axis. The months were reordered by starting with the wettest months indicated by \({P}_{R}-{E}_{P}\) (a), and the greenest months, indicated by NDVI (b). The late growing season is marked with white slashes, which starts with the month with maximum NDVI and ends when it decreases to half of the amplitude. The wet-to-dry transitional period is marked with white backslashes, which starts with the month with maximum cumulative \({P}_{R}-{E}_{P}\) and lasts for 3 months.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Hotspot regions of trends in annual \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{{{\bf{P}}}_{{\bf{P}}}}\), WDTP PR −EP, and LGS NDVI.

Trends of annual \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\) and WDTP \({P}_{R}-{E}_{P}\) in non-drylands (a, c), annual \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\) and LGS NDVI in drylands (b, d) from 1982 to 2021. Hotspots are defined as regions where the absolute values of \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\) trends exceed the 60th percentile, calculated separately for drylands and non-drylands.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Differences between NDVI and PR −EP in 2000‒2021 and 1982‒1999.

The results were presented in the two-dimensional space, with the reordered months of the year as x-axis and aridity levels as y-axis. The months were reordered by starting with the greenest months, indicated by NDVI (a‒b), and the wettest months indicated by \({P}_{R}-{E}_{P}\) (c‒d). The late growing season is marked with white slashes, while the wet-to-dry transitional period is marked with white backslashes.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison between \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{{{\bf{P}}}_{{\bf{P}}}}\) and its trend calculated from GLEAM4 and DGVMs outputs.

Dry and wet season mean \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\) during 2001‒2015, and trends in annual \({\beta }_{{P}_{P}}\) from 1982 to 2015 derived using 10-year moving windows. Dry and wet seasons were defined according to monthly mean \({P}_{R}\) and \({E}_{P}\) during 2001‒2015. Wet season is the period with monthly mean \({P}_{R}\) exceeding \({E}_{P}\); and the rest is dry season. For results based on GLEAM4, \({P}_{R}\) is from MSWEP, and \({E}_{P}\) is from GLEAM4; For results based on DGVMs outputs, both \({P}_{R}\) and \({E}_{P}\) are from CRU TS v4.07. Median values in drylands (marked as circles) and non-drylands (marked as rectangles) are illustrated with colors.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Vertical distribution of fine root biomass in response to climate change.

Climate change factors include elevated CO2 (a), warming (b), increased precipitation (c), and decreased precipitation (d). Each point represents the log response ratio (lnRR) for a specific soil layer in a single experiment: shallow (0–20 cm), median (20–50 cm), and deep (>50 cm). Red lines denote shifts toward deeper fine root distributions (higher lnRR in soils below 20 cm), whereas blue lines indicate shifts toward shallower distributions. Grey boxes show the distribution of lnRR values across soil layers.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–20, Supplementary Tables 1–3 and Supplementary Text 1–6.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., Miralles, D.G. et al. Increase in plant reliance on past precipitation associated with greening and drying. Nat Ecol Evol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-026-02997-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-026-02997-4