Abstract

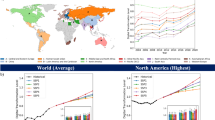

Developed democracies proliferated over the past two centuries during an unprecedented era of economic growth, which may be ending. Macroeconomic forecasts predict slowing growth throughout the twenty-first century for structural reasons such as ageing populations, shifts from goods to services, slowing innovation, and debt. Long-run effects of COVID-19 and climate change could further slow growth. Some sustainability scientists assert that slower growth, stagnation or de-growth is an environmental imperative, especially in developed countries. Whether slow growth is inevitable or planned, we argue that developed democracies should prepare for additional fiscal and social stress, some of which is already apparent. We call for a ‘guided civic revival’, including government and civic efforts aimed at reducing inequality, socially integrating diverse populations and building shared identities, increasing economic opportunity for youth, improving return on investment in taxation and public spending, strengthening formal democratic institutions and investing to improve non-economic drivers of subjective well-being.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Galor, O. & Weil, D. N. Population, technology, and growth: from Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 806–828 (2000).

World development indicators. World Bank https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (2020).

Roser, M. Democracy. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/democracy (2013).

Barro, R. J. Democracy and growth. J. Econ. Growth 1, 1–27 (1996).

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J.A. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (Currency, 2012).

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P. & Robinson, J. A. Democracy does cause growth. J. Polit. Econ. 127, 47–100 (2019).

Feng, Y. Democracy, political stability and economic growth. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 27, 391–418 (1997).

Barro, R. J. Determinants of democracy. J. Polit. Econ. 107, S158–S183 (1999).

Christensen, P., Gillingham, K. & Nordhaus, W. Uncertainty in forecasts of long-run economic growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5409–5414 (2018).

Kallis, G., Paulson, S., D’Alisa, G. & Demaria, F. The Case for Degrowth (Wiley, 2020).

Van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. Environment versus growth—a criticism of ‘degrowth’ and a plea for ‘a-growth’. Ecol. Econ. 70, 881–890 (2011).

2021 best global universities rankings. US News https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/rankings (2020).

Benjamin, D. J., Heffetz, O., Kimball, M. S. & Szembrot, N. Beyond happiness and satisfaction: toward well-being indices based on stated preference. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 2698–2735 (2014).

Putnam, R.D. Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004).

Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future (WW Norton, 2012).

Schenkkan, N. & Repucci, S. The freedom house survey for 2018: democracy in retreat. J. Democr. 30, 100–114 (2019).

Mounk, Y. The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom is in Danger and How to Save It (Harvard Univ. Press, 2018).

Hyde, S. D. Democracy’s backsliding in the international environment. Science 369, 1192–1196 (2020).

Hetherington, M.J. Why Trust Matters: Declining Political Trust and the Demise of American Liberalism (Princeton Univ. Press, 2005).

Vollrath, D. Fully Grown (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2020).

Gilding, P. The Great Disruption: Why the Climate Crisis Will Bring on the End of Shopping and the Birth of a New World (Bloomsbury, 2011).

Jackson, T. The post-growth challenge: secular stagnation, inequality and the limits to growth. Ecol. Econ. 156, 236–246 (2019).

Max Roser, H.R. & Ortiz-Ospina, E. World population growth. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/world-population-growth (2019).

World population prospects 2019. United Nations Population Division https://population.un.org/wpp/ (2019).

Vollset, S. E. et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet 396, 17–23 (2020).

Muto, I., Oda, T. & Sudo, N. Macroeconomic impact of population aging in Japan: a perspective from an overlapping generations model. IMF Econ. Rev. 64, 408–442 (2016).

Romer, P. M. The origins of endogenous growth. J. Econ. Perspect. 8, 3–22 (1994).

Jones, C.I. The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population, Technical Report (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Gordon, R.J. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living since the Civil War (Princeton Univ. Press, 2016).

Reinhart, C. M., Reinhart, V. R. & Rogoff, K. S. Public debt overhangs: advanced-economy episodes since 1800. J. Econ. Perspect. 26, 69–86 (2012).

Brynjolfsson, E. & McAfee, A. Race against the Machine: How the Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy (Digital Frontier, 2011).

Acemoglu, D. & Restrepo, P. Secular stagnation? The effect of aging on economic growth in the age of automation. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 174–179 (2017).

Brynjolfsson, E., Rock, D. & Syverson, C. The productivity J-curve: how intangibles complement general purpose technologies. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 13, 333–372 (2021).

Solow, R. M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 70, 65–94 (1956).

Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D. & Weil, D. N. A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 107, 407–437 (1992).

Baumol, W. J. Productivity growth, convergence, and welfare: what the long-run data show. Am. Econ. Rev. 76, 1072–1085 (1986).

Tilman, D., Balzer, C., Hill, J. & Befort, B. L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20260–20264 (2011).

Riahi, K. et al. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Chang 42, 153–168 (2017).

Dellink, R., Chateau, J., Lanzi, E. & Magné, B. Long-term economic growth projections in the shared socioeconomic pathways. Glob. Environ. Chang 42, 200–214 (2017).

Müller, U.K., Stock, J.H. & Watson, M.W. An Econometric Model of International Long-Run Growth Dynamics, Technical Report (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019).

Startz, R. The next hundred years of growth and convergence. J. Appl. Econ. 35, 99–113 (2020).

De Resende, C. An Assessment of IMF Medium-Term Forecasts of GDP Growth, IEO Background Paper No. BP/14/01 (IMF, 2014).

Frankel, J. Over-optimism in forecasts by official budget agencies and its implications. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 27, 536–562 (2011).

Frankel, J. & Schreger, J. Over-optimistic official forecasts and fiscal rules in the Eurozone. Rev. World Econ. 149, 247–272 (2013).

Burgess, M.G., Langendorf, R.E., Ippolito, T. & Pielke Jr, R. Optimistically biased economic growth forecasts and negatively skewed annual variation. Preprint at https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/vndqr (2020).

Burgess, M. G., Ritchie, J., Shapland, J. & Pielke, R. Jr IPCC baseline scenarios have over-projected CO2 emissions and economic growth. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 014016 (2021).

Baldwin, R. & di Mauro, B.W. Economics in the Time of COVID-19. A VoxEU.org Book (Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2020).

Timmermann, A. An evaluation of the world economic outlook forecasts. IMF Staff. Pap. 54, 1–33 (2007).

Bricker, D. & Ibbitson, J. Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline (Hachette, 2019).

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235–239 (2015).

Woodard, D. L., Davis, S. J. & Randerson, J. T. Economic carbon cycle feedbacks may offset additional warming from natural feedbacks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 759–764 (2019).

Brown, P. T., Moreno-Cruz, J. & Caldeira, K. Break-even year: a concept for understanding intergenerational trade-offs in climate change mitigation policy. Environ. Res. Commun. 2, 095002 (2020).

Kolstad, C. D. & Moore, F. C. Estimating the economic impacts of climate change using weather observations. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 14, 1–24 (2020).

Burgess, S. & Sievertsen, H.H. Schools, skills, and learning: the impact of COVID-19 on education. VoxEU https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education (2020).

Maliszewska, M., Mattoo, A. & Van Der Mensbrugghe, D. The potential impact of COVID-19 on GDP and trade: a preliminary assessment. World Bank https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33605 (2020).

Ranald, P. COVID-19 pandemic slows global trade and exposes flaws in neoliberal trade policy. J. Aust. Polit. Econ. 85, 108–114 (2020).

Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow (Taylor & Francis, 2016).

Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecol. Econ. 70, 873–880 (2011).

Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist (Chelsea Green, 2017).

Kallis, G. Radical dematerialization and degrowth. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 375, 20160383 (2017).

Ayres, R.U. & Warr, B. The Economic Growth Engine: How Energy and Work Drive Material Prosperity (Edward Elgar, 2010).

Furman, J. & Summers, L.A. Reconsideration of fiscal policy in the era of low interest rates. Brookings https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/furman-summers-fiscal-reconsideration-discussion-draft.pdf (2020).

General government deficit (indicator). OECD https://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-deficit.htm (2020).

Krugman, P. Financing vs. forgiving a debt overhang. J. Dev. Econ. 29, 253–268 (1988).

Cole, H. L. & Kehoe, T. J. Self-fulfilling debt crises. Rev. Econ. Stud. 67, 91–116 (2000).

De Santis, R.A. The Euro area sovereign debt crisis: safe haven, credit rating agencies and the spread of the fever from Greece, Ireland and Portugal, ECB working paper. European Central Bank https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1419.pdf (2012).

Blanchard, O. J. & Leigh, D. Growth forecast errors and fiscal multipliers. Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 117–120 (2013).

Blanchard, O. Public debt and low interest rates. Am. Econ. Rev. 109, 1197–1229 (2019).

General government debt (indicator). OECD https://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-debt.htm#indicator-chart (2020).

Patinkin, D. Money, Interest, and Prices: An Integration of Monetary and Value Theory (Harper & Row, 1965).

Ball, L. & Romer, D. Real rigidities and the non-neutrality of money. Rev. Econ. Stud. 57, 183–203 (1990).

Tymoigne, E. & Wray, L. R. Modern money theory 101: a reply to critics, working paper series. Levy Institute https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_778.pdf (2013).

Mankiw, N. G. A skeptic’s guide to Modern Monetary Theory. AEA Pap. Proc. 110, 141–144 (2020).

Webb, S.B. Hyperinflation and Stabilization in Weimar Germany (Oxford Univ. Press, 1989).

Pittaluga, G. B., Seghezza, E. & Morelli, P. The political economy of hyperinflation in Venezuela. Public Choice 186, 337–350 (2021).

Fabricant, M. & Brier, S. Austerity Blues: Fighting for the Soul of Public Higher Education (JHU Press, 2016).

Li, D., Richards, M. R. & Wing, C. Economic downturns and nurse attachment to federal employment. Heal. Econ. 28, 808–814 (2019).

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. & Borra, C. Retirement decisions in recessionary times: evidence from Spain. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 17, 20160201 (2017).

Hoynes, H., Miller, D. L. & Schaller, J. Who suffers during recessions? J. Econ. Perspect. 26, 27–48 (2012).

Turchin, P. & Nefedov, S.A. Secular Cycles (Princeton Univ. Press, 2009).

Shin, D. & Alam, M. S. Lean management strategy and innovation: moderation effects of collective voluntary turnover and layoffs. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell.–https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2020.1826923 (2020).

Ono, H. Why do the Japanese work long hours? Sociololgical perspectives on long working hours Japan. Jpn. Labor Issues 2, 35–49 (2018).

Manacorda, M. & Moretti, E. Why do most Italian youths live with their parents? Intergenerational transfers and household structure. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 4, 800–829 (2006).

Ponzellini, A. M. Work–life balance and industrial relations in Italy. Eur. Soc. 8, 273–294 (2006).

Pastore, F. Why is youth unemployment so high and different across countries? IZA World Labor https://wol.iza.org/articles/why-is-youth-unemployment-so-high-and-different-across-countries/long (2018).

Marelli, E. & Vakulenko, E. Youth unemployment in Italy and Russia: aggregate trends and individual determinants. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 27, 387–405 (2016).

Lyken-Segosebe, D. & Hinz, S. E. The politics of parental involvement: how opportunity hoarding and prying shape educational opportunity. Peabody J. Educ. 90, 93–112 (2015).

Reeves, R.V. Dream Hoarders: How the American Upper Middle Class Is Leaving Everyone Else in the Dust, Why That Is a Problem, and What to Do about It (Brookings Institution Press, 2018).

Gutiérrez, G. & Philippon, T. Declining competition and investment in the US, technical report. National Bureau of Economic Research https://www.nber.org/papers/w23583 (2017).

Putnam, R. D. & Romney Garrett, S. The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again (Simon & Schuster, 2020).

Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard Univ. Press, 2014).

Krusell, P. & Smith, A. A. Jr Is Piketty’s ‘second law of capitalism’ fundamental? J. Polit. Econ. 123, 725–748 (2015).

Jackson, T. & Victor, P. Confronting inequality in the new normal: basic income, factor substitution and the future of work, technical report, CUSP working paper. Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity https://cusp.ac.uk/themes/s2/wp11/ (2018).

Roser, M. & Ortiz-Ospina, E. Income inequality. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/income-inequality (2013).

Brady, D. & Finnigan, R. Does immigration undermine public support for social policy? Am. Sociol. Rev. 79, 17–42 (2014).

Rueda, D. Food comes first, then morals: redistribution preferences, parochial altruism, and immigration in Western Europe. J. Polit. 80, 225–239 (2018).

Alesina, A., Baqir, R. & Easterly, W. Public goods and ethnic divisions. Q. J. Econ. 114, 1243–1284 (1999).

Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S. & Wacziarg, R. Fractionalization. J. Econ. Growth 8, 155–194 (2003).

Alesina, A. & Ferrara, E. L. Ethnic diversity and economic performance. J. Econ. Lit. 43, 762–800 (2005).

Putnam, R. D. E pluribus unum: diversity and community in the twenty-first century: the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize lecture. Scand. Polit. Stud. 30, 137–174 (2007).

McGhee, H. The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together (One World, 2021).

Debelle, G. Macroeconomic implications of rising household debt. Preprint at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=786385 (2007).

Barba, A. & Pivetti, M. Rising household debt: its causes and macroeconomic implications—a long-period analysis. Camb. J. Econ. 33, 113–137 (2009).

Bernardini, M. & Peersman, G. Private debt overhang and the government spending multiplier: evidence for the United States. J. Appl. Econ. 33, 485–508 (2018).

Hirayama, Y. & Izuhara, M. Housing in Post-growth Society: Japan on the Edge of Social Transition (Routledge, 2018).

Ananat, E. O., Gassman-Pines, A., Francis, D. V. & Gibson-Davis, C. M. Linking job loss, inequality, mental health, and education. Science 356, 1127–1128 (2017).

Kurz, C.J., Li, G. & Vine, D.J. in Handbook of US Consumer Economics (Haughwout, A., & Mandel, B. eds.) 193–232 (Academic, 2019).

Case, A. & Deaton, A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15078–15083 (2015).

Davies, J. C. Toward a theory of revolution. Am. Sociol. Rev. 27, 5–19 (1962).

Twenge, J.M. IGen: Why Today’s Super-connected Kids Are Growing up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy–and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood–and What That Means for the Rest of Us (Simon and Schuster, 2017).

Fertility rates (indicator). OECD https://data.oecd.org/pop/fertility-rates.htm (2020).

Koo, J. & Cox, W. M. An economic interpretation of suicide cycles in Japan. Contemp. Econ. Policy 26, 162–174 (2008).

Suwa, M. & Suzuki, K. The phenomenon of ‘hikikomori’ (social withdrawal) and the socio-cultural situation in Japan today. J. Psychopathol. 19, 191–198 (2013).

Harper, S., Charters, T. J., Strumpf, E. C., Galea, S. & Nandi, A. Economic downturns and suicide mortality in the USA, 1980–2010: observational study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 956–966 (2015).

Durkheim, E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology (Routledge, 1952).

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I. & Seeman, T. E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51, 843–857 (2000).

Pfeti, A. & Miotto, P. Social and economic influence on suicide: a study of the situation in Italy. Arch. Suicide Res. 5, 141–156 (1999).

Detotto, C. et al. The role of family in suicide rate in Italy. Econ. Bull. 31, 1509–1519 (2011).

Deisenhammer, E. Weather and suicide: the present state of knowledge on the association of meteorological factors with suicidal behaviour. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 108, 402–409 (2003).

Autor, D., Dorn, D. & Hanson, G. When work disappears: manufacturing decline and the falling marriage market value of young men. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 1, 161–178 (2019).

Blau, J. R. & Blau, P. M. The cost of inequality: metropolitan structure and violent crime. Am. Sociol. Rev. 47, 114–129 (1982).

AEI-Brookings Working Group on Poverty and Opportunity. Opportunity, responsibility, and security: a consensus plan for reducing poverty and restoring the American dream. Brookings https://www.brookings.edu/research/opportunity-responsibility-and-security-a-consensus-plan-for-reducing-poverty-and-restoring-the-american-dream/ (2015).

Stoet, G. & Geary, D. C. A simplified approach to measuring national gender inequality. PloS ONE 14, e0205349 (2019).

Wall, H.J. The ‘man-cession’ of 2008–2009: It’s big, but it’s not great. The Reg. Econ. https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/october-2009/the-mancession-of-20082009-its-big-but-its-not-great (2009).

Hobijn, B., Sahin, A. & Song, J. The unemployment gender gap during the 2007 recession. Curr. Issues Econ. Financ. 16, 1–7 (2010).

Alon, T. M., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J. & Tertilt, M. The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality, technical report. National Bureau of Economic Research https://www.nber.org/papers/w26947 (2020).

Evertsson, M. & Duvander, A.-Z. Parental leave—possibility or trap? Does family leave length effect Swedish women’s labour market opportunities? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 27, 435–450 (2011).

Bansak, C., Graham, M. E. & Zebedee, A. A. Business cycles and gender diversification: an analysis of establishment-level gender dissimilarity. Am. Econ. Rev. 102, 561–565 (2012).

Castrillo, C., Martín, M. P., Arnal, M. & Serrano, A. in Poverty, Crisis and Resilience (eds Boost, M. et al.) 143–160 (Edward Elgar, 2020).

Mutz, D. C. Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E4330–E4339 (2018).

Mikucka, M., Sarracino, F. & Dubrow, J. K. When does economic growth improve life satisfaction? Multilevel analysis of the roles of social trust and income inequality in 46 countries, 1981–2012. World Dev. 93, 447–459 (2017).

Chaves, C., Castellanos, T., Abrams, M. & Vazquez, C. The impact of economic recessions on depression and individual and social well-being: the case of Spain (2006–2013). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 53, 977–986 (2018).

Searing, E. A. Love thy neighbor? Recessions and interpersonal trust in Latin America. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 94, 68–79 (2013).

Gurr, T. R. On the political consequences of scarcity and economic decline. Int. Stud. Q. 29, 51–75 (1985).

Miguel, E., Satyanath, S. & Sergenti, E. Economic shocks and civil conflict: an instrumental variables approach. J. Polit. Econ. 112, 725–753 (2004).

Miguel, E. & Satyanath, S. Re-examining economic shocks and civil conflict. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 3, 228–232 (2011).

Blattman, C. & Miguel, E. Civil war. J. Econ. Lit. 48, 3–57 (2010).

Bjørnskov, C. in The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust (ed. Uslaner, E.M.) Ch. 22 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2018).

Public trust in government: 1958–2021. Pew Research https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/05/17/public-trust-in-government-1958-2021/ (2021).

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., Lochner, K. & Prothrow-Stith, D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am. J. Public Health 87, 1491–1498 (1997).

Winters, J. A. & Page, B. I. Oligarchy in the United States? Perspect. Polit. 7, 731–751 (2009).

Piketty, T. Brahmin left vs merchant right: rising inequality and the changing structure of political conflict, WID world working paper 7. L’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/Piketty2018.pdf (2018).

Gilens, M. & Page, B. I. Testing theories of American politics: elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect. Polit. 12, 564–581 (2014).

Montalvo, J. G. & Reynal-Querol, M. Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. Am. Econ. Rev. 95, 796–816 (2005).

Chua, A. Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations (Penguin Books, 2019).

Brown, D. E. Human Universals (McGraw Hill, 1991).

Brewer, M. B. Ingroup identification and intergroup conflict. Soc. Identity Intergroup Confl. Confl. Reduct. 3, 17–41 (2001).

Fiske, S. T. What we know now about bias and intergroup conflict, the problem of the century. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 11, 123–128 (2002).

Allport, G. W. The Nature of Prejudice (Addison-Wesley, 1954).

Pettigrew, T. F. Intergroup contact theory. Annu. Rev. Psych. 49, 65–85 (1998).

Stolle, D. & Harell, A. Social capital and ethno-racial diversity: learning to trust in an immigrant society. Polit. Stud. 61, 42–66 (2013).

Sigelman, L. & Welch, S. The contact hypothesis revisited: black–white interaction and positive racial attitudes. Soc. Forces 71, 781–795 (1993).

Boisjoly, J., Duncan, G. J., Kremer, M., Levy, D. M. & Eccles, J. Empathy or antipathy? The impact of diversity. Am. Econ. Rev. 96, 1890–1905 (2006).

Merlino, L. P., Steinhardt, M. F. & Wren-Lewis, L. More than just friends? School peers and adult interracial relationships. J. Labor Econ. 37, 663–713 (2019).

Dixon, J., Durrheim, K. & Tredoux, C. Beyond the optimal contact strategy: a reality check for the contact hypothesis. Am. Psychol. 60, 697–711 (2005).

Herrmann, M. Population aging and economic development: anxieties and policy responses. J. Popul. Ageing 5, 23–46 (2012).

Musterd, S. & Ostendorf, W. Urban Segregation and the Welfare State: Inequality and Exclusion in Western Cities (Routledge, 2013).

Kumlin, S. & Rothstein, B. Making and breaking social capital: the impact of welfare-state institutions. Comp. Polit. Stud. 38, 339–365 (2005).

Hamilton, D. & Darity, W. Jr. Can ‘baby bonds’ eliminate the racial wealth gap in putative post-racial America? Rev. Black Polit. Econ. 37, 207–216 (2010).

Chetty, R. Improving equality of opportunity: new insights from big data. Contemp. Econ. Policy 39, 7–41 (2021).

Western, B. & Rosenfeld, J. Unions, norms, and the rise in US wage inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 76, 513–537 (2011).

Ortiz-Ospina, E., Beltekian, D. & Roser, M. Trade and globalization. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization (2018).

Fallows, J. & Fallows, D. Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America (Vintage, 2018).

McChrystal, S. How a national service year can repair America. The Washington Post (14 November 2014).

Collier, P. Exodus: How Migration Is Changing Our World (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Ager, P. & Brückner, M. Cultural diversity and economic growth: evidence from the US during the age of mass migration. Eur. Econ. Rev. 64, 76–97 (2013).

Bove, V. & Elia, L. Migration, diversity, and economic growth. World Dev. 89, 227–239 (2017).

Klein, E. Why We’re Polarized (Simon and Schuster, 2020).

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P. & Zingales, L. Does culture affect economic outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 20, 23–48 (2006).

Schulz, J. F., Bahrami-Rad, D., Beauchamp, J. P. & Henrich, J. The church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science 366, aau5141 (2019).

Henrich, J. The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020).

Baker, J. O., Martí, G., Braunstein, R., Whitehead, A. L. & Yukich, G. Religion in the age of social distancing: how COVID-19 presents new directions for research. Soc. Relig. 81, 357–370 (2020).

Mitchell, J. American Awakening: Identity Politics and Other Afflictions of Our Time (Encounter Books, 2020).

McWhorter, J. The elect: the threat to a progressive America from anti-Black antiracists. Substack https://johnmcwhorter.substack.com/p/the-elect-neoracists-posing-as-antiracists (2021).

Bellah, R. N. Civil religion in America. Daedalus 96, 1–21 (1967).

Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K. & Gaertner, S. L. in Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination (ed. Oskamp, S.) 137–163 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 2000).

Richeson, J. A. & Nussbaum, R. J. The impact of multiculturalism versus color-blindness on racial bias. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40, 417–423 (2004).

Krugman, P. End This Depression Now! (WW Norton, 2012).

Papanicolas, I., Woskie, L. R. & Jha, A. K. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319, 1024–1039 (2018).

Akitoby, B., Clements, B., Gupta, S. & Inchauste, G. Public spending, voracity, and Wagner’s law in developing countries. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 22, 908–924 (2006).

Lamartina, S. & Zaghini, A. Increasing public expenditure: Wagner’s law in OECD countries. Ger. Econ. Rev. 12, 149–164 (2011).

Rodrik, D. Why do more open economies have bigger governments? J. Polit. Econ. 106, 997–1032 (1998).

Saez, E. & Zucman, G. Progressive wealth taxation. Brookings https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Saez-Zuchman-final-draft.pdf (2019).

Hauser, W. K. There’s no escaping Hauser’s law. The Wall Street Journal (26 November 2010).

Value added tax in Denmark: a guide for non-resident businesses. Price Waterhouse Coopers https://www.pwc.dk/da/publikationer/2017/pwc-value-added-tax-in-denmark.pdf (2017).

Metcalf, G. E. Value-added taxation: a tax whose time has come? J. Econ. Perspect. 9, 121–140 (1995).

Kallis, G., Kerschner, C. & Martinez-Alier, J. The economics of degrowth. Ecol. Econ. 84, 172–180 (2012).

Van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. & Kallis, G. Growth, a-growth or degrowth to stay within planetary boundaries? J. Econ. Issues 46, 909–920 (2012).

Stevenson, B. & Wolfers, J. Subjective well-being and income: is there any evidence of satiation? Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 598–604 (2013).

Ortiz-Ospina, E. Happiness and life satisfaction. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-lifesatisfaction (2013).

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. D. World happiness report 2018. World Happiness Report https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2018/ (2018).

Hendriks, M. Does migration increase happiness? It depends. Migration Policy Institute https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/does-migration-increase-happiness-it-depends (2018).

Jebb, A. T., Tay, L., Diener, E. & Oishi, S. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 33–38 (2018).

Layard, P. R. G. & Layard, R. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science (Penguin, 2011).

Kahneman, D. & Deaton, A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16489–16493 (2010).

Kaufman, S. B. Transcend: The New Science of Self-actualization (JP Tarcher/Perigee Books, 2020).

Yang, A. The War on Normal People: The Truth about America’s Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future (Hachette, 2018).

Cowen, T. The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All the Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better: A Penguin eSpecial from Dutton (Penguin, 2011).

Roser, M. Economic growth. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/economic-growth (2020).

World Economic Outlook, April 2020: The Great Lockdown, Technical Report (International Monetary Fund, 2020).

Real GDP forecast (indicator). OECD https://data.oecd.org/gdp/real-gdp-forecast.htm (2020).

Budget and economic data. US CBO https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data (2020).

CBO. An evaluation of CBO’s past deficit and debt projections, technical report. Congress of the United States https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55234 (2019).

Atkinson, A.B., Hasell, J., Morelli, S. & Roser, M. The chartbook of economic inequality. The chartbook of economic inequality https://www.chartbookofeconomicinequality.com/ (2017).

IMF. Household debt, loans and debt securities. IMF https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/HH_LS@GDD/ (2020).

Roser, M. Fertility rate. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/fertility-rate (2014).

Hannah Ritchie, M.R. & Ortiz-Ospina, E. Suicide. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/suicide (2015).

OECD. Trust in government. OECD https://www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm (2020)

Ortiz-Ospina, E. Trust. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/trust (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Boileau, M. Kimball, R. Langendorf, W. Eichhorst, T. Ippolito, M. Hegwood, R. Marshall, two anonymous reviewers, and participants in several classes and seminars for helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This work was funded by the University of Colorado Boulder and the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (start-up grant to M.G.B.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.B. conceived the study and analysed the data. M.G.B., A.P., A.R.C., S.D.G. and S.V. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Human Behaviour thanks Giorgos Kallis and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Regression coefficients, 95% confidence intervals, and P values from Fig. 2e,f.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burgess, M.G., Carrico, A.R., Gaines, S.D. et al. Prepare developed democracies for long-run economic slowdowns. Nat Hum Behav 5, 1608–1621 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01229-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01229-y

This article is cited by

-

From Security to Freedom— The Meaning of Financial Well-being Changes with Age

Journal of Family and Economic Issues (2024)

-

Multidecadal dynamics project slow 21st-century economic growth and income convergence

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)