Abstract

Driven by access to large volumes of movement data, the study of human mobility has grown rapidly over the past few decades. The field has shown that human mobility is scale-free, proposed models to generate scale-free moving distance distributions and explained how the scale-free distribution arises. It has not, however, explicitly addressed how mobility is structured by geographical constraints, such as how mobility relates to the outlines of landmasses, lakes and rivers and the placement of buildings, roadways and cities. On the basis of millions of moves, we show how separating the effect of geography from mobility choices reveals a power law spanning five orders of magnitude. To do so, we incorporate geography via the pair distribution function, which encapsulates the structure of locations on which mobility occurs. By showing how the spatial distribution of human settlements shapes human mobility, our approach bridges the gap between distance- and opportunity-based models of human mobility.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data for Denmark used in this study are not publicly available due to Danish Data Protection regulations. However, access to the data is possible for research purposes. The data can be obtained via Statistics Denmark for Researchers in accordance with Statistics Denmark’s Research Scheme: https://www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice/. The location data for France are publicly available at https://adresse.data.gouv.fr/donnees-nationales and https://www.data.gouv.fr. The residential mobility data were obtained from https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques. The Foursquare data are publicly available at https://sites.google.com/site/yangdingqi/home/foursquare-dataset. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The geography model and estimation code are available via GitHub at https://github.com/benmaier/ljhouses. The code for the figures, data and statistical analysis is available via GitHub at https://github.com/LCB0B/role-of-geo. The code is also available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14329837 (ref. 68).

References

Fujita, M. et al. The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions, and International Trade (MIT Press, 2001).

Colizza, V., Barrat, A., Barthélemy, M. & Vespignani, A. The role of the airline transportation network in the prediction and predictability of global epidemics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2015–2020 (2006).

Brockmann, D. & Helbing, D. The hidden geometry of complex, network-driven contagion phenomena. Science 342, 1337–1342 (2013).

Setton, E. et al. The impact of daily mobility on exposure to traffic-related air pollution and health effect estimates. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 21, 42–48 (2011).

Coutrot, A. et al. Entropy of city street networks linked to future spatial navigation ability. Nature 604, 104–110 (2022).

Pumain, D. Pour une théorie évolutive des villes. Espace Géogr. 26, 119–134 (1997).

Arcaute, E. Hierarchies defined through human mobility. Nature 587, 372–373 (2020).

Arcaute, E. & Ramasco, J. J. Recent advances in urban system science: models and data. PLoS ONE 17, e0263200 (2022).

Brockmann, D., Hufnagel, L. & Geisel, T. The scaling laws of human travel. Nature 439, 462–465 (2006).

Gonzalez, M. C., Hidalgo, C. A. & Barabasi, A.-L. Understanding individual human mobility patterns. Nature 453, 779–782 (2008).

Schläpfer, M. et al. The universal visitation law of human mobility. Nature 593, 522–527 (2021).

Zipf, G. K. The p1p2/d hypothesis: on the intercity movement of persons. Am. Sociol. Rev. 11, 677–686 (1946).

Simini, F., González, M. C., Maritan, A. & Barabási, A.-L. A universal model for mobility and migration patterns. Nature 484, 96–100 (2012).

Alessandretti, L., Sapiezynski, P., Sekara, V., Lehmann, S. & Baronchelli, A. Evidence for a conserved quantity in human mobility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 485–491 (2018).

Alessandretti, L., Aslak, U. & Lehmann, S. The scales of human mobility. Nature 587, 402–407 (2020).

Pumain, D. (ed.) Hierarchy in Natural and Social Sciences (Springer, 2006).

Arcaute, E. et al. Cities and regions in Britain through hierarchical percolation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 3, 150691 (2016).

Wilson, A. G. Entropy in Urban and Regional Modelling (Pion, 1970).

Ripley, B. D. Modelling spatial patterns. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 39, 172–212 (1977).

Samaniego, H. & Moses, M. E. Cities as organisms: allometric scaling of urban road networks. J. Transp. Land Use 1, 21–39 (2008).

Lee, M., Barbosa, H., Youn, H., Holme, P. & Ghoshal, G. Morphology of travel routes and the organization of cities. Nat. Commun. 8, 2229 (2017).

Batty, M. & Longley, P. Fractal Cities: A Geometry of Form and Function (Academic Press, 1994).

Frankhauser, P. The fractal approach: a new tool for the spatial analysis of urban agglomerations. Popul. Engl. Sel. 10, 205–240 (1998).

Barbosa, H. et al. Human mobility: models and applications. Phys. Rep. 734, 1–74 (2018).

Carrothers, V. A historical review of the gravity and potential concepts of human interaction. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 22, 94–102 (1956).

Wilson, A. G. A statistical theory of spatial distribution models. Transp. Res. 1, 253–269 (1967).

Stouffer, S. Intervening opportunities: a theory relating mobility and distance. Am. Sociol. Rev. 5, 845–867 (1940).

Noulas, A., Scellato, S., Lambiotte, R., Pontil, M. & Mascolo, C. A tale of many cities: universal patterns in human urban mobility. PLoS ONE 7, e40692 (2012).

Mazzoli, M. et al. Field theory for recurrent mobility. Nat. Commun. 10, 3895 (2019).

Yan, X.-Y., Wang, W.-X., Gao, Z.-Y. & Lai, Y.-C. Universal model of individual and population mobility on diverse spatial scales. Nat. Commun. 8, 1639 (2017).

Han, X.-P., Hao, Q., Wang, B.-H. & Zhou, T. Origin of the scaling law in human mobility: hierarchy of traffic systems. Phys. Rev. E 83, 036117 (2011).

Hong, I., Jung, W.-S. & Jo, H.-H. Gravity model explained by the radiation model on a population landscape. PLoS ONE 14, e0218028 (2019).

Cohen, J. E. & Courgeau, D. Modeling distances between humans using Taylor’s law and geometric probability. Math. Popul. Stud. 24, 197–218 (2017).

Gao, Q. et al. Identifying human mobility via trajectory embeddings. In Proc. 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ed. Sierra, C.) 1689–1695 (International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence, 2017).

Murray, D. et al. Unsupervised embedding of trajectories captures the latent structure of scientific migration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2305414120 (2023).

Hansen, J.-P. & McDonald, I. R. Theory of Simple Liquids: with Applications to Soft Matter 2nd edn (Academic Press, 1986).

Nijkamp, P. & Reggiani, A. A Synthesis Between Macro and Micro Models in Spatial Interaction Analysis, with Special Reference to Dynamics Tech. Rep. (VU Univ. Amsterdam, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, 1986).

Clark, C. Urban population densities. J. R. Stat. Soc. A 114, 490–496 (1951).

Newling, B. E. The spatial variation of urban population densities. Geogr. Rev. 59, 242–252 (1969).

Bertaud, A. & Malpezzi, S. The Spatial Distribution of Population in 48 World Cities: Implications for Economies in Transition Working Paper (Center for Urban Land Economics Research, Univ. Wisconsin, 2003).

Duranton, G. & Puga, D. in Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics Vol. 4 (eds Henderson, J. V. & Thisse, J.-F.) 2063–2117 (Elsevier, 2004).

Lennard-Jones, J. E. Cohesion. Proc. Phys. Soc. 43, 461–482 (1931).

Ornstein, L. S. & Zernike, F. Accidental deviations of density and opalescence at the critical point of a single substance. Proc. R. Netherlands Acad. Arts Sci. 17, 793–806 (1914).

Christaller, W. Die Zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland (Gustav Fischer, 1933).

Soneira, R. M. & Peebles, P. J. E. A computer model universe: simulation of the nature of the galaxy distribution in the Lick catalog. Astron. J. 83, 845–860 (1978).

Makse, H. A., Havlin, S. & Stanley, H. E. Modelling urban growth patterns. Nature 377, 608–612 (1995).

Cadwallader, M. Migration and Residential Mobility: Macro and Micro Approaches (Univ. Wisconsin Press, 1992).

Pappalardo, L., Manley, E., Sekara, V. & Alessandretti, L. Future directions in human mobility science. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 7 (2023).

Clark, W. A., Huang, Y. & Withers, S. Does commuting distance matter? Commuting tolerance and residential change. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 33, 199–221 (2003).

Weber, A. & Friedrich, C. J. Alfred Weber’s Theory of the Location of Industries (Univ. Chicago Press, 1929).

Moduldata for Befolkning og Valg (Danmarks Statistik, 2024); https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/dokumentation/Times/moduldata-for-befolkning-og-valg

Api Documentation for Adgangsadresse (Dataforsyningen, 2023); https://dawadocs.dataforsyningen.dk/dok/api/adgangsadresse

Schlosser, F., Sekara, V., Brockmann, D. & Garcia-Herranz, M. Biases in human mobility data impact epidemic modeling. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.12521 (2021).

Wesolowski, A., Eagle, N., Noor, A. M., Snow, R. W. & Buckee, C. O. The impact of biases in mobile phone ownership on estimates of human mobility. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20120986 (2013).

Jacobsen, R., Møller, H. & Mouritsen, A. Natural variation in the human sex ratio. Hum. Reprod. 14, 3120–3125 (1999).

Births (Statistics Denmark, 2024); https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/emner/borgere/befolkning/foedsler

Campello, R. J., Moulavi, D. & Sander, J. Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In Proc. Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (PAKDD) (eds Pei, J. et al.) 160–172 (Springer, 2013).

Yang, D., Zhang, D. & Qu, B. Participatory cultural mapping based on collective behavior data in location-based social networks. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 7, 30:1–30:23 (2015).

Runfola, D. et al. geoBoundaries: a global database of political administrative boundaries. PLoS ONE 15, e0231866 (2020).

Liang, X., Zhao, J., Dong, L. & Xu, K. Unraveling the origin of exponential law in intra-urban human mobility. Sci. Rep. 3, 2983 (2013).

Maier, B. F. Generalization of the small-world effect on a model approaching the Erdős–Rényi random graph. Sci. Rep. 9, 9268 (2019).

Verlet, L. Computer experiments on classical fluids. I. Thermodynamical properties of Lennard–Jones molecules. Phys. Rev. 159, 98 (1967).

Berendsen, H. J., Postma, J. V., Van Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Clauset, A., Shalizi, C. R. & Newman, M. E. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM Rev. 51, 661–703 (2009).

Hanel, R., Corominas-Murtra, B., Liu, B. & Thurner, S. Fitting power-laws in empirical data with estimators that work for all exponents. PLoS ONE 12, e0170920 (2017).

Bauke, H. Parameter estimation for power-law distributions by maximum likelihood methods. Eur. Phys. J. B 58, 167–173 (2007).

Maier, B. F. Maximum-likelihood fits of piece-wise Pareto distributions with finite and non-zero core. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.09589 (2023).

Boucherie, L., Maier, B. & Lehmann, S. Decomposing geographical and universal aspects of human mobility. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14329837 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Dzubiella and Y. Ahn for helpful comments in the early development of this study, as well as L. Alessandretti and S. De Sojo for providing insightful comments on the manuscript. The work was supported in part by the Villum Foundation Grant Nation-Scale Social Networks (grant no. 00034288) (S.L.) and the Danish Council for Independent Research (grant no. 0136-00315B) (S.L.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B., B.F.M. and S.L. designed the study and the model. L.B. and B.F.M. performed the analyses and implemented the model. L.B., B.F.M. and S.L. analysed the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Ed Manley, Tao Zhou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

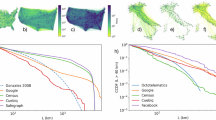

Extended Data Fig. 1 Pair distribution of buildings and addresses in France.

Pair distribution of buildings and addresses in France shows three scales: (I) Immediate neighborhood-scale with linear onset and oscillating modulation, (II) city-scale with power-law growth (α = 0.67, for addresses), and (III) country-scale with slower growth and rapid decay (see Supplementary Section 1.6).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Demographic characteristics of the Danish Residential Mobility dataset.

The gender imbalance is the first panel due to the 1.07 male/female ratio rate at birth55. Indeed, we study the total population, not the currently alive population, that is balanced for gender due higher death rate for men. Therefore, although there is an imbalance in gender, the dataset is not biased. The second panel shows the birth year of every individual in the dataset, it closely follows the birth rate of Denmark, and the differences are due to migrations56.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Age Distribution.

Distribution of Age at the time of moving in the Danish residential mobility data (see Methods: Data).

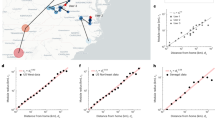

Extended Data Fig. 4

Comparison between our framework, the gravity model and the radiation model for cities.

Extended Data Fig. 5

A continuous gravity law.

(a) This framework can be represented as a continuous gravity law, if we take a toy model of two distant cities, (b) the pair distribution at the distance d between the two cities collapses into a Dirac distribution, with the height equal to the product of cities population, N1N2. (c) The toy intrinsic distance cost of the simulation model. For a comparison with a continuous radiation model, see Supplementary Section 3.1.2.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Distribution values for fitting the power laws.

Source Data Fig. 4

Distribution values for fitting the piecewise power laws.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Boucherie, L., Maier, B.F. & Lehmann, S. Decoupling geographical constraints from human mobility. Nat Hum Behav (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02282-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02282-7