Abstract

The gut microbiome of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) has been characterized, but its role in influencing host immunity and associated clinical features are unclear. Here we used shotgun metagenomics to characterize the faecal microbiome of two geographically distinct cohorts of PLWH and healthy controls in Israel and Ethiopia. We uncovered disease-specific, geographically divergent microbial patterns including a shift from Bacteroides to Prevotella species in an Israeli cohort and multiple Enterobacteriaceae species including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella quasivariicola in an Ethiopian cohort. We identified correlations between human immunodeficiency virus-related dysbiosis and the extent of systemic immunodeficiency, as proxied by peripheral CD4+ T cell counts. Faecal microbiome transplantation from PLWH with high peripheral CD4+ T cell counts induced colonic epithelium-associated CD4+ T cells in germ-free or antibiotic-treated recipient mice. Impaired epithelium-associated lymphocyte induction in recipients of faecal microbiome transplantation from severely immunodeficient PLWH donors was associated with altered protection from Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Collectively, our results suggest a link between systemic immunodeficiency and associated intestinal dysbiosis in PLWH, resulting in impaired gut mucosal immunity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All shotgun metagenomic and transcriptomic sequencing data analysed in this study are available via the European Nucleotide Archive at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home under accession number PRJEB81733.

The source data underlying this study are available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30834287 (ref. 65).

References

Brenchley, J. M. et al. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200, 749–759 (2004).

Marcus, J. L. et al. Comparison of overall and comorbidity-free life expectancy between insured adults with and without HIV infection, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e207954 (2020).

Cohn, L. B., Chomont, N. & Deeks, S. G. The biology of the HIV-1 latent reservoir and implications for cure strategies. Cell Host Microbe 27, 519–530 (2020).

Wang, H. & Kotler, D. P. HIV enteropathy and aging: gastrointestinal immunity, mucosal epithelial barrier, and microbial translocation. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 9, 309–316 (2014).

Thompson, C. G. et al. Heterogeneous antiretroviral drug distribution and HIV/SHIV detection in the gut of three species. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaap8758 (2019).

Sandler, N. G. & Douek, D. C. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 655–666 (2012).

Hsue, P. Y. & Waters, D. D. HIV infection and coronary heart disease: mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 745–759 (2019).

Leng, S. X. & Margolick, J. B. Understanding frailty, aging, and inflammation in HIV infection. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 12, 25–32 (2015).

Hepworth, M. R. et al. Innate lymphoid cells regulate CD4+ T-cell responses to intestinal commensal bacteria. Nature 498, 113–117 (2013).

Mazmanian, S. K., Liu, C. H., Tzianabos, A. O. & Kasper, D. L. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell 122, 107–118 (2005).

Dillon, S. M. et al. An altered intestinal mucosal microbiome in HIV-1 infection is associated with mucosal and systemic immune activation and endotoxemia. Mucosal Immunol. 7, 983–994 (2014).

Dinh, D. M. et al. Intestinal microbiota, microbial translocation, and systemic inflammation in chronic HIV infection. J. Infect. Dis. 211, 19–27 (2015).

Monaco, C. L. et al. Altered virome and bacterial microbiome in human immunodeficiency virus-associated acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cell Host Microbe 19, 311–322 (2016).

Zheng, D., Liwinski, T. & Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 30, 492–506 (2020).

Lozupone, C. A. Unraveling interactions between the microbiome and the host immune system to decipher mechanisms of disease. mSystems 3, e00183-17 (2018).

Neff, C. P. et al. Fecal microbiota composition drives immune activation in HIV-infected individuals. EBioMedicine 30, 192–202 (2018).

Finzi, D. et al. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 5, 512–517 (1999).

Guillén, Y. et al. Low nadir CD4+ T-cell counts predict gut dysbiosis in HIV-1 infection. Mucosal Immunol. 12, 232–246 (2019).

Tuddenham, S., Koay, W. L. & Sears, C. HIV, sexual orientation, and gut microbiome interactions. Dig. Dis. Sci. 65, 800–817 (2020).

Ling, Z. et al. Alterations in the fecal microbiota of patients with HIV-1 infection: an observational study in a Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 6, 30673 (2016).

Lozupone, C. A. et al. Alterations in the gut microbiota associated with HIV-1 infection. Cell Host Microbe 14, 329–339 (2013).

Ishizaka, A. et al. Unique gut microbiome in HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) suggests association with chronic inflammation. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e0070821 (2021).

Caniglia, E. C. et al. When to monitor CD4 cell count and HIV RNA to reduce mortality and AIDS-defining illness in virologically suppressed HIV-positive persons on antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a prospective observational study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 72, 214–221 (2016).

Pacheco, Y. M. et al. Increased risk of non-AIDS-related events in HIV subjects with persistent low CD4 counts despite cART in the CoRIS cohort. Antiviral Res. 117, 69–74 (2015).

Kaufmann, G. R. et al. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41, 361–372 (2005).

Jabbar, K. S. et al. Human immunodeficiency virus and antiretroviral therapies exert distinct influences across diverse gut microbiomes. Nat. Microbiol. 10, 2720–2735 (2025).

Peltenburg, N. C. et al. Persistent metabolic changes in HIV-infected patients during the first year of combination antiretroviral therapy. Sci. Rep. 8, 16947 (2018).

Zaongo, S. D. et al. Candida albicans can foster gut dysbiosis and systemic inflammation during HIV infection. Gut Microbes 15, 2167171 (2023).

Vujkovic-Cvijin, I. et al. HIV-associated gut dysbiosis is independent of sexual practice and correlates with noncommunicable diseases. Nat. Commun. 11, 2448 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. The altered metabolites contributed by dysbiosis of gut microbiota are associated with microbial translocation and immune activation during HIV infection. Front. Immunol. 13, 1020822 (2022).

Hamad, I. et al. Metabarcoding analysis of eukaryotic microbiota in the gut of HIV-infected patients. PLoS ONE 13, e0191913 (2018).

Zhao, Q. & Elson, C. O. Adaptive immune education by gut microbiota antigens. Immunology 154, 28–37 (2018).

Chakrabarti, A. K. et al. Detection of HIV-1 RNA/DNA and CD4 mRNA in feces and urine from chronic HIV-1 infected subjects with and without anti-retroviral therapy. AIDS Res. Ther. 6, 20 (2009).

Bieniasz, P. D. & Cullen, B. R. Multiple blocks to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in rodent cells. J. Virol. 74, 9868–9877 (2000).

Victor Garcia, J. Humanized mice for HIV and AIDS research. Curr. Opin. Virol. 19, 56–64 (2016).

Whitney, J. B. & Brad Jones, R. In vitro and in vivo models of HIV latency. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1075, 241–263 (2018).

Wang, R. J., Li, J. Q., Chen, Y. C., Zhang, L. X. & Xiao, L. H. Widespread occurrence of Cryptosporidium infections in patients with HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, clinical feature, diagnosis, and therapy. Acta Trop. 187, 257–263 (2018).

Kaur, U. S. et al. High abundance of genus Prevotella in the gut of perinatally HIV-infected children is associated with IP-10 levels despite therapy. Sci. Rep. 8, 17679 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. HIV infection and microbial diversity in saliva. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 1400–1411 (2014).

Sperk, M. et al. Fecal metabolome signature in the HIV-1 elite control phenotype: enrichment of dipeptides acts as an HIV-1 antagonist but a Prevotella agonist. J. Virol. 95, e0047921 (2021).

Dillon, S. M. et al. Gut dendritic cell activation links an altered colonic microbiome to mucosal and systemic T-cell activation in untreated HIV-1 infection. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 24–37 (2016).

O’Connor, J. B. et al. Agrarian diet improves metabolic health in HIV-positive men with Prevotella-rich microbiomes: results from a randomized trial. mSystems 10, e0118525 (2025).

Paulo, L. S. et al. Urbanization gradient, diet, and gut microbiota in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Front. Microbiomes 2, 1–17 (2023).

Nordling, L. Homophobia and HIV research: under siege. Nature 509, 274–275 (2014).

Eribo, O. A., du Plessis, N. & Chegou, N. N. The intestinal commensal, Bacteroides fragilis, modulates host responses to viral infection and therapy: lessons for exploration during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 90, e0032121 (2022).

Johnson, J. L., Jones, M. B. & Cobb, B. A. Polysaccharide A from the capsule of Bacteroides fragilis induces clonal CD4+ T cell expansion. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 5007–5014 (2015).

Ramakrishna, C. et al. Bacteroides fragilis polysaccharide A induces IL-10 secreting B and T cells that prevent viral encephalitis. Nat. Commun. 10, 2153 (2019).

Mazmanian, S. K., Round, J. L. & Kasper, D. L. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature 453, 620–625 (2008).

Deng, H. et al. Bacteroides fragilis prevents Clostridium difficile infection in a mouse model by restoring gut barrier and microbiome regulation. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2976 (2018).

Veazey, R. S. Intestinal CD4 depletion in HIV/SIV infection. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 15, 76–91 (2019).

Costiniuk, C. T. & Angel, J. B. Human immunodeficiency virus and the gastrointestinal immune system: does highly active antiretroviral therapy restore gut immunity?. Mucosal Immunol. 5, 596–604 (2012).

Hada, A. & Xiao, Z. Ligands for intestinal intraepithelial T lymphocytes in health and disease. Pathogens 14, 109 (2025).

McDonald, B. D., Jabri, B. & Bendelac, A. Diverse developmental pathways of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 514–525 (2018).

Suez, J. et al. Post-antibiotic gut mucosal microbiome reconstitution is impaired by probiotics and improved by autologous FMT. Cell 174, 1406–1423.e16 (2018).

Zmora, N. et al. Personalized gut mucosal colonization resistance to empiric probiotics is associated with unique host and microbiome features. Cell 174, 1388–1405.e21 (2018).

Furuichi, M. et al. Commensal consortia decolonize Enterobacteriaceae via ecological control. Nature 633, 878–886 (2024).

Zeevi, D. et al. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell 163, 1079–1094 (2015).

Blacher, E. et al. Potential roles of gut microbiome and metabolites in modulating ALS in mice. Nature 572, 474–480 (2019).

Manohar, P., Loh, B., Nachimuthu, R. & Leptihn, S. Phage-antibiotic combinations to control Pseudomonas aeruginosa–Candida two-species biofilms. Sci. Rep. 14, 9354 (2024).

Thaiss, C. A. et al. Hyperglycemia drives intestinal barrier dysfunction and risk for enteric infection. Science 359, 1376–1383 (2018).

Huang, K. D. et al. Establishment of a non-Westernized gut microbiota in men who have sex with men is associated with sexual practices. Cell Rep. Med. 5, 101426 (2024).

Adiconis, X. et al. Comparative analysis of RNA sequencing methods for degraded or low-input samples. Nat. Methods 10, 623–629 (2013).

Li, X. et al. A comparison of per sample global scaling and per gene normalization methods for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. PLoS ONE 12, e0176185 (2017).

Fontaine, M. & Guillot, E. Development of a TaqMan quantitative PCR assay specific for Cryptosporidium parvum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 214, 13–17 (2002).

Bashiardes, S., Valdes-Mas, R., Heinemann, M. & Elinav, E. source data_NMICROBIOL-24124010E. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30834287.v3 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Elinav laboratory, Weizmann Institute of Science, and Microbiome and Cancer Division, DKFZ, for insightful discussions; C. Bar-Nathan for dedicated GF mouse husbandry; and D. Kviatcovsky for help with experiments. We thank R. Nir-Paz and J. Strahilevitz of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel, for key help and advice. M. Heinemann was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation, 438122637). L.A. received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement Number 842203. R.V.-M. was a recipient of a senior postdoctoral fellowship from the Weizmann Institute of Science. H.S. is the incumbent of the Vera Rosenberg Schwartz Research Fellow Chair. J.P. is supported by the Helmholtz Foundation and the DKFZ Hector Cancer Institute at the University Medical Center Mannheim, Germany. E.E. is supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, European Research Council, Israel Science Foundation, Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, Israel Ministry of Health, Helmholtz Foundation, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization, Kenneth Rainin Foundation, Rising Tide Foundation, Lupus Research Alliance, Jose Carreras Foundation, Human Frontiers Science Program, Deutsch-Israelische Projektkooperation, IDSA Foundation, European Union THRIVE consortium (J.P. and E.E., HORIZON-MISS-2023-CANCER) and the Nutriome consortium. E.E. is the incumbent of the Sir Marc and Lady Tania Feldmann Professorial Chair, a Kimmel researcher, a CIFAR fellow and a partner of the Novo Nordisk Foundation Microbiome Health Initiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., M. Heinemann, L.A. and R.V.-M. designed, performed, analysed and interpreted the experiments and wrote the paper. J.A.M. headed, coordinated and analysed human trials and experiments. S.B., M. Heinemann, L.A., R.V.-M. and J.A.M. equally contributed to the work. Y.C. and U.M. helped with the computational aspects and provided critical insights. S.P.N., T.T., T.Y., M. Heinemann, M.D.A., S.F., N.A., Z.B., A.D., J.P., I.A. and N.Z. provided critical insights or helped with the experiments. N.S. and H.S. coordinated the key animal experimentation. M.Z., A.B. and S.E.-M. coordinated human trials and handled human data and sample collection. S.I., M.K., Y.O., K.O.-P., E.O.-H., D.E., R.C.-P., D.T., T.H., H.G., Y.K. and E.V. headed the clinical trials, shared samples and metadata, and provided key experimental insights. M.D.-B., S.M. and S.S. performed sample processing and next-generation DNA sequencing. A.H. performed histopathological scoring. H.E. and E.E. conceived the study, supervised the participants, interpreted the experiments and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.E. is an advisor to Purposebio and Zoe in topics unrelated to this work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks Namita Rout and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

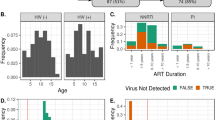

Extended Data Fig. 1 Table summarizing the characteristics of the Israeli study cohort living with HIV.

aIf more than one sample was provided before initiation of ART, only the first sample was chosen and numeric parameters are related to the time the first sample was collected. bIf more than one sample was provided during ART, only the last sample was chosen, and numeric parameters are related to the time the last sample was collected. cViral load was undetectable in 2 samples from untreated individuals and in 48 samples from individuals on ART. Data are given as median (IQR) or n (%). ART, antiretroviral treatment; HC, healthy control; MSM, men who have sex with men; PLWH, people living with human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; F, female; M, male.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Characterization of the gut microbiome in an Israeli cohort of PLWH by shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

(a) Differential species abundance between untreated PLWH and HC, controlling for mode of transmission. Wald test with FDR correction (DESeq2). Dashed lines: p adjusted of 0.05. Differentially abundant species are shown in color according to disease status; black, non-differentially abundant species. (b) Differential species abundance between PLWH on ART and HC, controlling for mode of transmission. Wald test with FDR correction (DESeq2). Dashed lines: p adjusted of 0.05. Differentially abundant species are shown in color according to disease status; black, non-differentially abundant species. (c–d) Alpha diversity analysis comparing untreated PLWH, PLWH on ART, and HC, as shown in Fig. 2a and Fig. 2c, was repeated after excluding individuals with MSM behavior. Two-sided Mann-Whitney test (p = 0.0165). (c) Simpson’s diversity index comparing untreated PLWH (n = 46) and HC (n = 20); values are plotted as mean ± SEM. (d) Simpson’s diversity index comparing PLWH on ART (n = 42) and HC (n = 20); values are plotted as mean ± SEM. (e) Linear model showing the association between CD4⁺ T cell counts and blood CRP levels in PLWH (simple linear regression, p < 0.019). (f) Pairwise comparison of the Simpson’s index between untreated PLWH and PLWH on ART (n = 55/group). Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Plotted values represent mean ± SEM. (g) PCoA of pairwise comparison between untreated PLWH and PLWH on ART. PERMANOVA. (h) Pairwise comparison of differential species abundance between untreated PLWH and PLWH on ART, controlling for patientID. Wald test with FDR correction (DESeq2). Dashed lines: p adjusted of 0.05. Differentially abundant species are shown in color according to the group of PLWH; black, non-differentially abundant species. For pairwise comparisons, the first blood and stool sample collected before initiation of ART and the last blood and stool sample collected during ART were compared. (i–j) Differential viral species abundance between (i) untreated PLWH and (j) PLWH on ART compared to HC, controlling for mode of transmission. Wald test with FDR correction (DESeq2). Differentially abundant viral species are colored according to disease status; non-significant species are shown in black. * p < 0.05; ART, antiretroviral treatment; HC, healthy controls; PCoA, principal coordinate analysis; PC, principal component; PLWH, people living with human immunodeficiency virus; Padj, adjusted P value.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Table summarizing the characteristics of the Ethiopian study cohort living with HIV.

ART, antiretroviral treatment; HC, healthy controls; PLWH, people living with human immunodeficiency virus.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterization of the gut microbiome in an Ethiopian cohort of PLWH by shotgun metagenomic sequencing and gating strategy for IEL CD4+ T cells after FMT to recipient mice.

(a) Heatmap of microbial species enriched or decreased in PLWH and healthy household controls from Ethiopia. (b) Gating strategy for IEL CD4 + T cells. TCRb, T Cell Receptor Beta chain; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HC, healthy controls; PLWH, people living with human immunodeficiency virus.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Fecal microbiome transplantation from PLWH to recipient mice.

(a-e) FMT experiments including different human donors (related to Fig. 5). Fecal samples from PLWH with low ( < 200 µl−1) or high ( ≥ 500 µl−1) peripheral blood CD4+ T cells and HC were transplanted into mice. As control, PBS was gavaged. (a) Frequency of intestinal epithelium-associated CD4⁺ T cells among all live epithelium-associated cells in two pooled experiments (Low, n = 12; High, n = 11). Data are presented as mean values +/- SEM. (p = 0.0439). (b-e) Measured fractions of CD4+ T cells in different compartments were normalized to the PBS group: colonic Lamina propria (p = 0.0005; PBS, n = 3; Low, n = 5; High, n = 3; b), small intestine Lamina propria (PBS, n = 3; Low, n = 5; High, n = 3; c), spleen (p = 0.0247; PBS, n = 3; Low, n = 5; High, n = 3; d) and blood (PBS, n = 4; Low, n = 3; High, n = 4, HC, n = 4; e). Data are presented as median values +/- IQR. (f-h) Measurement of the small intestinal length (Low, n = 8; High, n = 7; f), transit time by the fraction of Evans blue 30 minutes after gavage of Evans blue Low, n = 8; High, n = 7; g) and gut permeability by the amount of FITC-dextran detected in the peripheral blood three hours upon oral gavage of FITC dextran (Low, n = 16; High, n = 16; h). Box plots show the median, interquartile range, and minimum/maximum values. Two-sided unpaired t-test. ns, not significant; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001. HC, healthy controls; FITC, Fluorescein isothiocyanate; ns, not significant; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; SI, small intestine; high, PLWH with high peripheral blood CD4+ T cells ( ≥ 500 µl−1); low, PLWH with low peripheral blood CD4+ T cells ( < 200 µl−1).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Characterization of gene expression profiles in rectal biopsies in an Israeli cohort of PLWH and microbial profiles from stool samples of FMT- and PBS-treated mice.

(a) Study design. PLWH with low ( < 200 µl−1) and high ( ≥ 500 µl−1) peripheral blood CD4+ T cells and HC underwent endoscopy. A rectal biopsy for bulk RNA sequencing was collected. (b) Principal component analysis (PC) of transcriptomic profiles between the three groups. (c) Differentially expressed genes between the low and high group. Wald test with FDR correction (DESeq2). Dashed lines: p adjusted of 0.05. Differentially abundant genes are shown in color; black, non-differentially abundant genes. (d) PC analysis of microbial profiles from stool samples of FMT-treated mice and PBS-treated controls from two independent experiments. HC, healthy controls; high, PLWH with high peripheral blood CD4+ T cells ( ≥ 500 µl−1); low, PLWH with low peripheral blood CD4+ T cells ( < 200 µl−1); ns, not significant; PC, principal component; FC, fold change; PLWH, people living with human immunodeficiency virus; FMT, fecal microbiome transplantation; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Padj, adjusted P value.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bashiardes, S., Heinemann, M., Adlung, L. et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated gut microbiome impacts systemic immunodeficiency and susceptibility to opportunistic gut infection. Nat Microbiol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02253-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02253-8