Abstract

Topological Kondo insulators are a topologically protected insulating state induced by Kondo exchange interactions between itinerant electrons and local magnetic moments, as opposed to single-particle band inversion. They are characterized by an insulating bulk with Dirac surface states in three dimensions and helical edge states in two dimensions. Although experiments have supported the emergence of these insulators in the rare-earth compound SmB6, their observation in two-dimensional systems has not been demonstrated. Here we report the experimental evidence of a two-dimensional topological Kondo insulator in MoTe2/WSe2 moiré bilayers. Using dual-gated devices, we prepare a triangular lattice of local moments in the MoTe2 layer and a half-filled dispersive band in the WSe2 layer with a chiral Kondo coupling. Using transport and compressibility measurements, we show that the state supports metallic transport at high temperature and an insulating bulk with helical edge conduction protected by spin-Sz conservation at low temperature. Under high magnetic fields, the insulating state at low temperature becomes metallic. Our results demonstrate a highly tunable platform based on moiré materials for studying the interplay of strong interactions and topological order.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

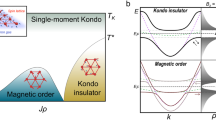

A topological Kondo insulator (TKI) arises from the interplay of strong electronic correlations and topology1,2,3. Its physics could be captured by the Anderson lattice model4,5,6, in which conduction electrons (c-electrons) support a dispersive energy band, localized electrons (f-electrons) support a flat band, and the two are coupled by a hybridization term (\(V\)). We start with a fully filled f-band. As the on-site Coulomb repulsion (\(U\)) for the f-electrons is adiabatically turned on, electrons are transferred from the f-band to the c-band3 (Fig. 1a–c). If the hybridization is topologically trivial, the system crosses over from a band insulator in the small-\(U\) limit to a Kondo insulator (KI) in the large-\(U\) limit with a half-filled f-band and c-band. However, if the hybridization is topologically non-trivial, a topological phase transition is expected from a band insulator to a TKI. Although the experimental evidence of a three-dimensional TKI7,8,9,10,11,12,13 has been reported, two-dimensional (2D) TKIs have remained elusive. The emergence of moiré materials14,15,16,17,18 provides an opportunity not only to realize a 2D TKI but also to control the state.

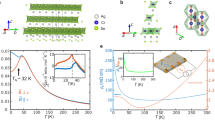

a, Schematic of a bilayer Anderson lattice model. Itinerant c-electrons and localized f-electrons with on-site Coulomb repulsion \(U\) are coupled by hybridization \(V.\) b, Schematic of the cross-section of dual-gated MoTe2/WSe2 moiré bilayers. Holes in the W layer and Mo layer play the role of c-electrons and f-electrons, respectively. c, Evolution from a band insulator (with a filled f-band and empty c-band) to a KI for non-topological \(V\) or TKI for topological \(V\) as \(U\) is adiabatically turned on. d, Electric-field-tuned phases in MoTe2/WSe2 moiré bilayers at a total hole filling of 2, from a band insulator (\({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}=2\) and \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=0\)) to a mixed-valence TI (\({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}} > 1\) and \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}} < 1\)) with a topological phase transition, to a TKI (\({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx {\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\approx 1\)) with a crossover. UHB, upper Hubbard band; LHB, lower Hubbard band. The dashed lines in c and d denote the Fermi levels. e–g, Local (e), non-local (f) and bulk (g) geometries for transport measurements. Connections of electrodes 0–9 to bias excitations, voltage probes and ground are illustrated.

In this study, we report the experimental evidence of a 2D TKI in angle-aligned MoTe2/WSe2 (referred to as Mo and W hereafter, respectively) moiré bilayers19,20,21. The 7% lattice mismatch between the transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers creates a honeycomb moiré lattice with a period of about 5 nm. The electronic states of interest are the (time-reversal conjugate) K- and K′-valley states near the valence band maxima in each layer, which are spin split by a large Ising spin–orbit coupling18,22. Density functional theory calculations23 have established that the Wannier orbitals of the Mo and W layers occupy the two sublattice sites of the honeycomb, respectively, and are coupled by a chiral interlayer hopping term. The topmost moiré valence bands of the Mo and W layers play the role of f-electrons and c-electrons, respectively, because the Mo band is substantially flatter than the W band due to its heavier hole mass and stronger moiré potential23,24. The large \(U\) in the Mo layer splits the doubly valley-degenerate band into the lower and upper Hubbard bands25 (Fig. 1d). Further, the W band can be continuously shifted up relative to the Mo Hubbard bands by varying an electric field (\(E\)) perpendicular to the sample plane to tune the interlayer potential difference19,20,21. The system, thus, realizes a tunable Anderson lattice model26,27,28,29,30,31,32.

Recent experiments have demonstrated both non-trivial band topology19,21 and a Kondo lattice20,33 in MoTe2/WSe2 moiré bilayers. A quantum anomalous Hall insulator was observed at total hole filling factor \(\nu =1\) (one hole per moiré unit cell) when the W band inverts with the lower Mo Hubbard band19; furthermore, a quantum spin Hall insulator (or topological insulator (TI)) was observed at \(\nu =2\) when the W band inverts with the upper Hubbard band19. In addition, a heavy Fermi liquid was demonstrated in the Kondo lattice regime when the Mo layer is kept in the Mott insulator state with filling factor \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}=1\) and the W layer is doped with filling factor \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) up to 0.35 (ref. 20). The topological nature of the interlayer (or Kondo exchange) coupling suggests the possibility of stabilizing a 2D TKI if one could achieve \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx {\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\approx 1\) in the Kondo lattice regime.

We fabricated dual-gated Hall bar devices of angle-aligned MoTe2/WSe2 moiré bilayers (Fig. 1b). The top and bottom gates allow independent control of \(\nu\) and \(E\). Crucially, we used a substantially thinner (about 3 nm) hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) top-gate dielectric than in previous studies19,20,21. It enabled us to access higher electric fields (>1 V nm−1, limited by dielectric breakdown) to study the Kondo lattice regime with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx 1\) and \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) ranging from zero to above one. The angle-aligned bilayers yield the longest moiré period to maximize the electronic correlations.

We carried out electrical transport measurements in the local, bulk and non-local geometries (Fig. 1e–g). The local and non-local geometries34,35 are dominated by edge conduction; the bulk geometry, in which edge conduction is substantially suppressed36, provides a proxy for the bulk resistivity measurement. The latter was supplemented by the compressibility measurement, from which we estimated the bulk charge gap. We studied five devices and observed consistent results in all devices. The results from devices 1 and 2 are presented (Extended Data Fig. 1 shows the device images). All the measurements were performed at a temperature of T = 1.6 K unless otherwise specified. Methods provides details on device fabrication, electrical transport and compressibility measurements.

Kondo lattice

Figure 2a,b shows the four-terminal longitudinal resistance \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) measured using the local geometry as a function of \(\nu\) and \(E\) under an out-of-plane magnetic field \({B}_{\perp }=0\) T and 14 T, respectively. The grey-shaded regions are inaccessible due to dielectric breakdown at high electric fields and poor electrical contacts at low electric fields. We also show the electrostatic phase diagram constructed from the data in Fig. 2c and the corresponding energy band diagrams in Fig. 2d. They are fully consistent with earlier studies19,20,21, including the prominent insulating states at \(\nu\) = 1, which are a Mott insulator at lower electric fields with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) = 1 and \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) = 0 and a quantum anomalous Hall insulator near \(E=0.75\) V nm−1 with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}+{\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\).

a,b, Local longitudinal resistance \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) at \(T=1.6\) K as a function of \(\nu\) and \(E\) under \({B}_{\perp }=0\) T (a) and 14 T (b). c,d, Electrostatic phase diagram extracted from experiment (c) and band alignment for the representative phase regions (d). Band hybridization is not shown for simplicity. Holes are shared in both layers inside the region bounded by the orange dashed lines. The Kondo lattice regime is bounded by the blue lines. The black line in a denotes the linecut for \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) dependence studies in this experiment. In d, the red and purple lines denote the Mo Hubbard bands and dispersive W band, respectively; the dashed lines denote the Fermi levels (the results are from device 1).

We focus on the Kondo lattice regime with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) = 1 and variable \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (Fig. 2c, shaded area bounded by the two blue dashed lines). Figure 2b shows that under 14 T, for which the itinerant hole spins and the local moments are fully polarized, the Kondo singlets cannot form. The resistance is dominated by Shubnikov–de Haas (SdH) oscillations due to the formation of spin–valley-polarized Landau levels in the W layer (the Mo layer has a much lower mobility and weaker SdH oscillations). The SdH oscillations in the Kondo lattice regime manifest vertical stripes because for a given \(\nu\), the Fermi level remains inside the Mo Mott gap and the doping density in the W layer is independent of the electric field (Fig. 2d, top right). The electric-field span reveals the Mott gap size20, which decreases with increasing \(\nu\) due to the free-carrier screening of \(U\). From the temperature dependence of the SdH oscillations, we determined the hole effective mass to be around \(0.5{m}_{0}\) (\({m}_{0}\) denotes the free electron mass), which agrees with the value for W monolayers (Extended Data Fig. 2). We also observed a doubling of the Landau level degeneracy at \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\gtrsim 0.5\) when the Fermi energy exceeds the spin–valley-Zeeman splitting37,38.

Earlier works have reported a heavy Fermi liquid behaviour in the Kondo lattice regime for \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) up to 0.35 (ref. 20). With current devices, we were able to verify the behaviour for \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) approaching 1 (Methods and Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4). Specifically, at zero magnetic field and below the Kondo coherence temperature \({T}^{* }\), the resistance depends quadratically on temperature: \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}={R}_{0}+A{T}^{2}\), where \({R}_{0}\) is the disorder-limited residual resistance and the Kadowaki–Woods coefficient \(A\) scales with the quasiparticle mass \({m}^{* }\propto {A}^{0.5}\) (ref. 39). Above a critical magnetic field \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), the spins are fully polarized, Kondo singlets can no longer form, the effective mass drops to a value comparable with that in a W monolayer and SdH oscillations emerge. This is accompanied by a sign change in the Hall resistance and an abrupt jump in the Hall density. The effective Kondo exchange interaction, which is expressed in \({T}^{* }\), \({A}^{-0.5}\) and \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), increases with the itinerant hole density29,32,40. In the \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\to 1\) limit, we observed \({T}^{* }\) ≈ 30 K and \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\) ≈ 11 T.

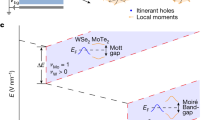

Evidence of TKI

We examine the state at \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx {\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\approx 1\) in the Kondo lattice regime by combining transport measurements using different geometries and demonstrate that it is a TI with protected helical edge states. We display \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) as a function of temperature under a zero magnetic field (Fig. 3a, filled symbols). Distinct from the Fermi liquid behaviour for \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}} < 1\), \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) shows a metallic behaviour only above about 20 K. Below 20 K, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) increases with decreasing temperature and saturates at about 16 kΩ (which is close to \(\frac{h}{2{e}^{2}}\), where \(h\) and \(e\) denote the Planck constant and electron charge, respectively). By contrast, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) exhibits a metallic temperature dependence over the entire temperature range when a magnetic field above \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\) is applied or when the local moments are depleted (\({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) = 0, \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) = 1; Fig. 3a, lines). The filling-factor-dependent resistance at 1.6 K also exhibits a broad peak around \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) = 1 (Fig. 3b, filled symbols) as \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) increases, whereas \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) is fixed at 1. Again, by contrast, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) has a weak dependence on \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) under a high magnetic field or in the absence of local moments.

a,b, Local or bulk resistance as a function of temperature (a) and W-layer hole filling factor \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (b) at 1.6 K. c, Penetration capacitance normalized by geometrical gate capacitances in a series combination (\({C}_{{\rm{p}}}/{C}_{{\rm{series}}}\)) at 1.6 K as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) near \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) = 1. The charge gap of the TKI is determined by the blue-shaded area. d, Non-local resistance \({R}_{{ij},{kl}}\) with source and drain electrode (k, l) and voltage probe pair (i, j) as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) at 1.6 K (\({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) = 1). Inset: equivalent circuit diagram, with each resistor carrying a resistance quantum. e, Dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) on \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) under varying \({B}_{\parallel }\) (top) and \({B}_{\perp }\) (bottom) at \(1.6\) K. f, Magnetic-field dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}(0\,\text{T})/{R}_{\mathrm{xx}}(B)\) at \(1.6\) K. Strong magnetoresistance is observed only for the TKI under an in-plane field. The dashed lines in a, b and d denote the expected quantized values (the results are shown from device 1, except for d, which are from device 2).

We measured the ‘bulk’ resistance \({R}_{{\rm{bulk}}}\) in the Kondo lattice regime using the bulk geometry (Fig. 3a,b, empty symbols). The bulk resistance shows a similar \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) dependence as \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) at 1.6 K, but with a substantially higher peak value. At \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\), \({R}_{{\rm{bulk}}}\) increases exponentially with decreasing temperature, demonstrating an insulating behaviour. To further exclude any potential edge contributions, we performed the compressibility measurement. Figure 3c shows the normalized penetration capacitance, or equivalently, the incompressibility as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\). It exhibits a pronounced peak at \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\). We determined the bulk charge gap from the peak area (shaded) to be about 1 meV. Consistent with the metallic transport behaviour shown in Fig. 3a, the system is compressible under 14 T or in the absence of local moments.

We also performed non-local transport measurements in the Kondo lattice regime. Figure 3d shows the non-local resistance, \({R}_{{ij},{kl}}\equiv \frac{{V}_{{ij}}}{{I}_{{kl}}}\), as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) for several electrode configurations (Extended Data Fig. 5a shows additional configurations). Here \({I}_{{kl}}\) is the bias current between the source and drain electrodes (k, l) and \({V}_{{ij}}\) is the voltage drop across the electrode pairs (i, j). Non-local resistances show pronounced peaks at \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\) and the peak size depends on the electrode configuration. For instance, the \({R}_{\mathrm{19,46}}\) peak (close to \(\frac{2h}{5{e}^{2}}\)) is about twice the \({R}_{\mathrm{98,46}}\) peak, which is about the same size but of opposite sign as the \({R}_{\mathrm{12,46}}\) peak. Non-local resistances are negligible away from \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\) for the metallic states.

We further probed transport in the Kondo lattice regime under \({B}_{\perp }\) or \({B}_{\parallel }\) (in-plane magnetic field) well below the value of \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\). Figure 3e shows \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) under varying magnetic fields. At \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\), \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) increases with increasing \({B}_{\parallel }\) and the normalized magnetoconductance \(\frac{{R}_{\mathrm{xx}}({B}_{\parallel }=0\,{\rm{T}})}{{R}_{\mathrm{xx}}({B}_{\parallel })}\) exhibits a cusp shape (Fig. 3f). The non-local resistance has a similar dependence on \({B}_{\parallel }\) (Extended Data Fig. 6b). As the temperature increases, the magnetoresistance decreases and disappears above about 20 K (Extended Data Fig. 6a). By contrast, the in-plane magnetoresistance is negligible away from \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\) for the metallic states; the out-of-plane magnetoresistance is negligible for any \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) in the entire range.

The results shown in Fig. 3 support a 2D TKI at \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx {\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\approx 1\) in the Kondo lattice regime. First, both bulk resistance and compressibility data indicate that the bulk is an insulator. Second, the nearly quantized \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) (about 20% higher than \(\frac{h}{2{e}^{2}}\)) at low temperatures suggests helical edge conduction. The imperfect quantization could originate from the coherence length of the helical edge states being comparable with or shorter than the electrode separation (about 2 µm). Better quantization was observed in device 2, with an electrode separation of 1 µm (Extended Data Fig. 7e). The observed non-local transport further supports edge conduction because non-local transport is exponentially suppressed for bulk conduction. We derived an equivalent circuit for helical edge transport using the Landauer–Büttiker formalism34 (Fig. 3d (inset) and Methods). It predicts \({R}_{\mathrm{19,46}}=2{R}_{\mathrm{98,46}}=\frac{2h}{5{e}^{2}}\) and \({R}_{\mathrm{98,46}}=-{R}_{\mathrm{12,46}}\), with which our experiment is consistent. In particular, the observation of \({R}_{\mathrm{98,46}}\approx -{R}_{\mathrm{12,46}}\) highlights the dominance of edge conduction because the resistances would be of the same sign if transport were dominated by bulk conduction. The imperfect quantization presumably arises from remnant bulk contributions and/or backscattering of the edge states (for instance, from magnetic impurities, thermal excitations and electron–electron interactions41,42,43,44,45,46). The former (latter) lowers (raises) the non-local resistances from the expected values.

Third, the anisotropic magnetoresistance is consistent with helical edge states being protected by spin-Sz conservation47,48. Since spin Sz remains a good quantum number under \({B}_{\perp }\), helical edge states persist and the magnetoresistance is negligible below \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\) (above \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), both itinerant hole spins and local moments are fully polarized and cannot form the TKI). On the other hand, even a small \({B}_{\parallel }\) destroys spin-Sz conservation (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 6); it induces backscattering of the edge states, resulting in a large positive magnetoresistance36,47,48. By contrast, the in-plane magnetoresistance is negligible for bulk states (away from \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}=1\)) because transition metal dichalcogenides possess a strong Ising spin–orbit coupling18.

Fourth, our experiment supports the fact that the TI in the Kondo lattice regime emerges due to hybridization between the iterant holes in the W layer and the local moments in the Mo layer via Kondo exchange interactions (Fig. 1b). The state is destroyed at temperatures above the Kondo temperature scale, for \({B}_{\perp }\) > \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), and on the depletion of the local moments. It is continuously connected to the heavy fermion liquid at \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}} < 1\) (refs. 3,49).

Kondo-lattice-to-mixed-valence crossover

Last, we comment on the high-resistance state at \(\nu =2\) that connects to the TKI at lower electric fields. Figure 4 shows the transport data as a function of \(\nu\) (near 2) and \(E\) from device 2. Two electric fields, \({E}_{1}\approx\) 0.52 V nm−1 and \({E}_{2}\approx\) 0.7 V nm−1, divide the \(\nu =2\) phase into three regimes from low to high fields: the regime with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) = 2, mixed valence with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}} > 1\) and \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}} < 1\), and Kondo lattice with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx {\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\approx 1\) (Fig. 4a). They were identified from the \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) map under 14 T (Fig. 4b), as discussed above. The \(\nu =2\) phase is a band insulator in the regime with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) = 2. This is supported by experiment, including comparable \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) and \({R}_{{\rm{bulk}}}\) (Fig. 4a,c), the insulating temperature dependence of the resistances and non-zero incompressibility (Extended Data Fig. 8). The \(\nu =2\) state in the mixed-valence regime is like the TKI in many aspects: \({R}_{{\rm{bulk}}}\) diverges at low temperatures, the state is incompressible, it shows non-local transport (Fig. 4d) with resistances that depend on the electrode configurations (Extended Data Fig. 5b) and it shows the same anisotropic magnetoresistance (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Yet, unlike the TKI, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) and non-local resistances at low temperatures far exceed \(\frac{h}{{e}^{2}}\) and the state is robust up to substantially higher magnetic fields (Fig. 4b).

a–d, Transport characteristics around total filling factor \(\nu =2\) as a function of \(\nu\) and \(E\): local resistance \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) under \({B}_{\perp }=0\) T (a) and 14 T (b), bulk resistance (c) and non-local resistance (d) under \({B}_{\perp }=0\) T. Resistances are shown in a log scale in a–c and a linear scale in d. Two electric fields (\({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\)) divide the \(\nu =2\) phase into three regimes from low to high fields: the regime with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\) = 2, mixed valence with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}} > 1\) and \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}} < 1\), and Kondo lattice with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx {\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\approx 1\) (between the two blue dashed lines; a). The results are shown from device 2 at 1.6 K.

The \(\nu =2\) state in the mixed-valence regime could also be a TI. It turns into a band insulator at \({E}_{1}\), where the charge gap closes. The behaviour is compatible with a topological phase transition induced by an electric-field-tuned inversion of the W band and the Mo upper Hubbard band19 (Fig. 1d). On the high-field end at \({E}_{2}\), the state smoothly evolves into the TKI with no discontinuity in the gap size and other observables (Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9). Such an adiabatic crossover is consistent with theoretical predictions26. The robustness of the state against higher \({B}_{\perp }\) could arise from its topological order induced by a band inversion rather than Kondo exchange interactions for the TKI. The high resistances (far exceeding the quantized values) of the state could arise from a short coherence length44,45,50, which may originate from enhanced backscattering of the helical edge states from strong electron–electron interactions. We observed a strong bias dependence for \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\), whose scaling shows a one-dimensional Luttinger liquid behaviour, indicating strong electron–electron interactions46,51,52,53 (Extended Data Fig. 10). We did not observe such a behaviour for the TKI. Future experiments are required to verify the mixed-valence TI. Our results pave the path for the further exploration of tunable topological Kondo physics in moiré materials.

Methods

Device fabrication

We fabricated dual-gated Hall bar devices of angle-aligned MoTe2/WSe2 bilayers using the layer-by-layer dry transfer method54,55. The constituent atomically thin flakes were exfoliated from bulk crystals onto Si substrates with a 285-nm SiO2 layer and identified by their optical reflection contrast. The flakes were picked up sequentially using a polycarbonate stamp to form heterostructures (Fig. 1b). The crystallographic orientations of the MoTe2 and WSe2 monolayers and their relative twist angles were determined by angle-resolved optical second-harmonic generation56,57 with about ±0.5° uncertainty. Before encapsulation by hBN, MoTe2 was handled in a nitrogen-filled glovebox to minimize sample oxidation.

To produce high-quality devices for transport studies, we divided the stacking process into several steps. We first released the bottom gate of few-layer graphite and hBN (about 10 nm) onto a Si/SiO2 substrate. Thin Pt electrodes (8 nm) were patterned into a Hall bar geometry on the hBN surface by electron-beam lithography and evaporation. Polymer residues were cleaned by atomic force microscopy in the contact mode with a typical force of 500 nN. The remaining stack, consisting of the MoTe2/WSe2 bilayer and the hBN/graphite top gate, was released onto the prepatterned Pt electrodes at 200 °C. The top graphite gate is narrower than the bottom graphite gate, and defines the device channel. This geometry allows us to study the electrical transport properties of the device channel without contributions from other parallel channels. Compared with earlier studies19,20, a thinner hBN top-gate dielectric (<4 nm) was used to achieve larger breakdown electric fields (about 1.4 V nm−1). We studied a total of five devices. All devices showed similar results.

Electrical measurements

The electrical transport measurements were performed in a closed-cycle 4He cryostat equipped with a 14-T superconducting magnet (Oxford TeslatronPT). Standard low-frequency (13.77 Hz) lock-in techniques were used to measure the four-terminal resistances with a 1-mV bias excitation at the source electrode. The voltage drop at the probe electrodes and the source–drain current (below 100 nA) were recorded. Different measurement geometries were used for the longitudinal and Hall resistances (Fig. 1e), the non-local resistances (Fig. 1f) and the bulk resistance (Fig. 1g). Voltage amplifiers with a large input impedance (100 MΩ) were used to measure the sample resistance up to about 10 MΩ. All data were taken at 1.6 K, unless otherwise specified.

Compressibility measurements

The compressibility measurements were performed using the same Hall bar devices and the same cryostat as the electrical transport measurements. Details have been reported in previous studies19,58. For the penetration capacitance \({C}_{{\rm{p}}}\), a 5-mV excitation was applied to the top gate, and a displacement current was collected from the bottom gate through a high-electron-mobility transistor with the MoTe2/WSe2 bilayer grounded. A commercial high-electron-mobility transistor (FHX35X) was mounted vertically on the same chip near the sample as the first-stage amplifier59,60 to eliminate parasitic capacitances. Standard lock-in techniques with a modulation frequency of 437.77 Hz were used for the differential capacitance measurement.

On the basis of a lumped circuit model, the penetration capacitance can be written as

Here \({C}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) is the quantum capacitance, \({C}_{{\rm{series}}}\equiv {C}_{{\rm{t}}}{C}_{{\rm{b}}}/({C}_{{\rm{t}}}{+C}_{{\rm{b}}})\) and \({C}_{{\rm{parallel}}}\equiv {C}_{{\rm{t}}}{+C}_{{\rm{b}}}\) are the series and parallel combinations of the geometrical top-gate capacitance (\({C}_{{\rm{t}}}\)) and bottom-gate capacitance (\({C}_{{\rm{b}}}\)), respectively. The thermodynamic gap of an insulating state can be obtained as \(\Delta \mu =e\int ({C}_{{\rm{p}}}/{C}_{{\rm{b}}}){\rm{d}}{V}_{\mathrm{tg}}\), where \({V}_{{\rm{tg}}}\) is the top-gate voltage.

Heavy Fermi liquid

Earlier studies have reported a heavy Fermi liquid behaviour in the Kondo lattice regime for \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) up to 0.35 (ref. 20). We were able to verify the behaviour for \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) approaching 1 in the current devices (Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4). The Kondo temperature \({T}^{* }\) is the energy scale below which the Kondo singlets form. It separates coherent and incoherent transport61. Above \({T}^{* }\), the unscreened local moments provide perturbative Kondo scattering to the itinerant holes, resulting in a weakly temperature-dependent resistance. Below \({T}^{* }\), the lattice of local moments is coherently screened, resulting in a quick drop in resistivity and the emergence of a coherent Landau Fermi liquid. We estimated \({T}^{* }\) as the temperature scale for a bump (or a change in the slope) in \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\left(T\right)\). Specifically, we extracted \({T}^{* }\) by identifying the intersection of two fitted lines representing the resistance in the coherent and incoherent transport regimes (Extended Data Fig. 4d). The low-temperature part of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\left(T\right)\) can be fitted with \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\left(T\right)={R}_{0}+A{T}^{2}\) (Extended Data Fig. 4c). The coefficient \(A\) provides a measure for the quasiparticle effective mass39, which is expected to scale with \({T}^{* }\) since \({m}^{* }\propto {A}^{0.5}\propto \frac{1}{{T}^{* }}\) (ref. 39). With increasing \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\), \({T}^{* }\) increases and approaches 30 K in the \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\to 1\) limit. This is consistent with the predicted strengthening of the effective Kondo exchange interaction with increasing itinerant hole density29,32,40.

We also examined \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) and \({R}_{\mathrm{xy}}\) (Hall resistance) or \({n}_{{\rm{H}}}=\frac{{B}_{\perp }}{e{R}_{\mathrm{xy}}}\) (Hall density) as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) and \({B}_{\perp }\) (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Linecuts at selected \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3c,d. As \({B}_{\perp }\) increases, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) first increases and reaches a maximum near a characteristic field \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\). Above \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) drops substantially and SdH oscillations emerge. Simultaneously, \({R}_{\mathrm{xy}}\) (\({n}_{{\rm{H}}}\)) changes sign at \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\) and \({n}_{{\rm{H}}}\) jumps by a step approximately of the moiré density \({n}_{{\rm{M}}}\). Here \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\) is the field required to fully polarize the itinerant hole spins and the local moments, which can no longer hybridize. Above \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), the Hall density reveals the hole density \(({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}})\) of the decoupled W band. At small fields, the Hall density reveals the density of the heavy Fermi liquid, which is \(\sim {1-\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) and electron like. Note that when \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\to 1\), a TKI emerges, and under low fields, \({n}_{{\rm{H}}}\) primarily probes the unbalanced Hall response. It is not related to the carrier density. Like \({T}^{* }\), \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\) increases with \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) and saturates at about 11 T in the \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\to 1\) limit (Extended Data Fig. 3).

Analysis of non-local transport

Non-local transport was measured following the scheme shown in Fig. 1f. The source–drain pair and the voltage probe pair are widely separated to minimize the bulk contribution34,35. In device 2, the channel is \(9\times 1\,{{\rm{\mu }}{\rm{m}}}^{2}\); the separation between the adjacent electrodes is \(1\,{\rm{\mu }}{\rm{m}}\). The diffusive bulk transport (probed away from \(\nu =2\)) leads to negligible non-local resistances, and non-local transport is dominated by edge conduction (Fig. 3d).

The non-local edge transport is well described by the Landauer–Büttiker formula62. In contrast to chiral edge states in the quantum Hall regime, the non-local resistance for a quantum spin Hall insulator is finite despite the non-dissipative nature of the helical edge states. There are two counterpropagating edge channels. They propagate at different chemical potentials inherited from the respective outlet contacts to form a net current flow. Quantum phase coherence is lost at the contacts, where the counterpropagating edge channels are forced to equilibrate. This results in a resistance quantum \(h/{e}^{2}\). Consequently, the non-local measurement circuit can be simplified to an equivalent resistance network (Fig. 3d, inset), with each resistor carrying a resistance quantum.

Figure 3d shows three different measurement configurations. Using the equivalent circuit model, we predict \({R}_{\mathrm{19,46}}=2h/5{e}^{2}\approx 10.3\,{\rm{k}}\Omega\) and \({R}_{\mathrm{98,46}}\approx -{R}_{\mathrm{12,46}}=h/5{e}^{2}\approx 5.2\,{\rm{k}}\Omega\). The measured values at \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}\approx {\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\approx 1\) agree reasonably well with these predictions. Additional phase decoherence for the edge states may also occur, for instance, at charge puddles induced by sample inhomogeneity near the edges. This will lead to an imperfect quantization of the resistances42,43,44.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Dzero, M., Sun, K., Galitski, V. & Coleman, P. Topological Kondo insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 106408 (2010).

Dzero, M., Sun, K., Coleman, P. & Galitski, V. Theory of topological Kondo insulators. Phys. Rev. B 85, 045130 (2012).

Dzero, M., Xia, J., Galitski, V. & Coleman, P. Topological Kondo insulators. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 7, 249–280 (2016).

Anderson, P. W. Localized magnetic states in metals. Phys. Rev. 124, 41 (1961).

Martin, R. M. & Allen, J. Theory of mixed valence: metals or small gap insulators. J. Appl. Phys. 50, 7561–7566 (1979).

Varma, C. Mixed-valence compounds. Rev. Mod. Phys. 48, 219 (1976).

Kim, D., Grant, T. & Fisk, Z. Limit cycle and anomalous capacitance in the Kondo insulator SmB6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 096601 (2012).

Wolgast, S. et al. Low-temperature surface conduction in the Kondo insulator SmB6. Phys. Rev. B 88, 180405 (2013).

Kim, D. et al. Surface Hall effect and nonlocal transport in SmB6: evidence for surface conduction. Sci. Rep. 3, 3150 (2013).

Zhang, X. et al. Hybridization, inter-ion correlation, and surface states in the Kondo insulator SmB6. Phys. Rev. 3, 011011 (2013).

Neupane, M. et al. Surface electronic structure of the topological Kondo-insulator candidate correlated electron system SmB6. Nat. Commun. 4, 2991 (2013).

Xu, N. et al. Direct observation of the spin texture in SmB6 as evidence of the topological Kondo insulator. Nat. Commun. 5, 4566 (2014).

Kim, D.-J., Xia, J. & Fisk, Z. Topological surface state in the Kondo insulator samarium hexaboride. Nat. Mater. 13, 466–470 (2014).

Andrei, E. Y. et al. The marvels of moiré materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 201–206 (2021).

Andrei, E. Y. & MacDonald, A. H. Graphene bilayers with a twist. Nat. Mater. 19, 1265–1275 (2020).

Balents, L., Dean, C. R., Efetov, D. K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity and strong correlations in moiré flat bands. Nat. Phys. 16, 725–733 (2020).

Kennes, D. M. et al. Moiré heterostructures as a condensed-matter quantum simulator. Nat. Phys. 17, 155–163 (2021).

Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Semiconductor moiré materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 686–695 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Quantum anomalous Hall effect from intertwined moiré bands. Nature 600, 641–646 (2021).

Zhao, W. et al. Gate-tunable heavy fermions in a moiré Kondo lattice. Nature 616, 61–65 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. Realization of the Haldane Chern insulator in a moiré lattice. Nat. Phys. 20, 275–280 (2024).

Xiao, D., Liu, G.-B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Zhang, Y., Devakul, T. & Fu, L. Spin-textured Chern bands in AB-stacked transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2112673118 (2021).

Rademaker, L. Spin-orbit coupling in transition metal dichalcogenide heterobilayer flat bands. Phys. Rev. B 105, 195428 (2022).

Devakul, T. & Fu, L. Quantum anomalous Hall effect from inverted charge transfer gap. Phys. Rev. 12, 021031 (2022).

Mendez-Valderrama, J. F., Kim, S. & Chowdhury, D. Correlated topological mixed-valence insulators in moiré heterobilayers. Phys. Rev. B 110, L201105 (2024).

Xie, F., Chen, L., Fang, Y. & Si, Q. Topological Kondo semimetals emulated in heterobilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Res. 7, 033093 (2025).

Guerci, D. et al. Topological Kondo semimetal and insulator in AB-stacked heterobilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 110, 165128 (2024).

Guerci, D. et al. Chiral Kondo lattice in doped MoTe2/WSe2 bilayers. Sci. Adv. 9, eade7701 (2023).

Xie, F., Chen, L. & Si, Q. Kondo effect and its destruction in heterobilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 013219 (2024).

Dalal, A. & Ruhman, J. Orbitally selective Mott phase in electron-doped twisted transition metal-dichalcogenides: a possible realization of the Kondo lattice model. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043173 (2021).

Kumar, A., Hu, N. C., MacDonald, A. H. & Potter, A. C. Gate-tunable heavy fermion quantum criticality in a moiré Kondo lattice. Phys. Rev. B 106, L041116 (2022).

Zhao, W. et al. Emergence of ferromagnetism at the onset of moiré Kondo breakdown. Nat. Phys. 20, 1772–1777 (2024).

Roth, A. et al. Nonlocal transport in the quantum spin Hall state. Science 325, 294–297 (2009).

Du, L., Knez, I., Sullivan, G. & Du, R.-R. Robust helical edge transport in gated InAs/GaSb bilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 096802 (2015).

Fei, Z. et al. Edge conduction in monolayer WTe2. Nat. Phys. 13, 677–682 (2017).

Gustafsson, M. V. et al. Ambipolar Landau levels and strong band-selective carrier interactions in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 411–415 (2018).

Han, Z. et al. Quantum oscillations between excitonic and quantum spin Hall insulators in moiré WSe2. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.19287 (2025).

Kadowaki, K. & Woods, S. Universal relationship of the resistivity and specific heat in heavy-fermion compounds. Solid State Commun. 58, 507–509 (1986).

Burdin, S., Georges, A. & Grempel, D. Coherence scale of the Kondo lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1048 (2000).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Väyrynen, J. I., Goldstein, M. & Glazman, L. I. Helical edge resistance introduced by charge puddles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 216402 (2013).

Väyrynen, J. I., Goldstein, M., Gefen, Y. & Glazman, L. I. Resistance of helical edges formed in a semiconductor heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B 90, 115309 (2014).

Maciejko, J. et al. Kondo effect in the helical edge liquid of the quantum spin Hall state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 256803 (2009).

Knez, I., Du, R.-R. & Sullivan, G. Evidence for helical edge modes in inverted InAs/GaSb quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 136603 (2011).

Li, T. et al. Observation of a helical Luttinger liquid in InAs/GaSb quantum spin Hall edges. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 136804 (2015).

Kang, K. et al. Evidence of the fractional quantum spin Hall effect in moiré MoTe2. Nature 628, 522–526 (2024).

Kang, K. et al. Double quantum spin hall phase in moiré WSe2. Nano Lett. 24, 14901–14907 (2024).

Coleman, P. Heavy Fermions: Electrons at the Edge of Magnetism (Wiley, 2007).

König, M. Spin-Related Transport Phenomena in HgTe-based Quantum Well Structures. PhD thesis, Universität Würzburg (2007).

Haldane, F. D. M. ‘Luttinger liquid theory’ of one-dimensional quantum fluids. I. Properties of the Luttinger model and their extension to the general 1D interacting spinless Fermi gas. J. Phys. C 14, 2585 (1981).

Kane, C. & Fisher, M. P. Transport in a one-channel Luttinger liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 1220 (1992).

Li, T., Wang, P., Sullivan, G., Lin, X. & Du, R.-R. Low-temperature conductivity of weakly interacting quantum spin Hall edges in strained-layer InAs/GaInSb. Phys. Rev. B 96, 241406 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Li, T. et al. Continuous Mott transition in semiconductor moiré superlattices. Nature 597, 350–354 (2021).

Tang, Y. et al. Simulation of Hubbard model physics in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 353–358 (2020).

Regan, E. C. et al. Mott and generalized Wigner crystal states in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 359–363 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Charge-order-enhanced capacitance in semiconductor moiré superlattices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1068–1072 (2021).

Ashoori, R. et al. Single-electron capacitance spectroscopy of discrete quantum levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 3088 (1992).

Zibrov, A. A. et al. Tunable interacting composite fermion phases in a half-filled bilayer-graphene Landau level. Nature 549, 360–364 (2017).

Pavarini, E., Coleman, P. & Koch, E. Many-Body Physics: From Kondo to Hubbard. Report No. 3958060749 (Theoretische Nanoelektronik, 2015).

Büttiker, M. Four-terminal phase-coherent conductance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 1761 (1986).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Chowdhury, D. Guerci, A. Millis, J. H. Pixley and Q. Si for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (grant DOI 10.37807/GBMF11563; transport measurements) and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award number FA9550-20-1-0219 (compressibility measurement). We used the Cornell NanoScale Facility, an NNCI member supported by NSF Grant NNCI-2025233, for sample fabrication. The growth of the hBN crystals was supported by the Elemental Strategy Initiative of MEXT, Japan, and CREST (JPMJCR15F3), JST. We also acknowledge support from the David and Lucile Packard Fellowship (K.F.M.).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. and Y.X. fabricated the devices. They performed the measurements and analysed the data with the help of Z.X., W.Z. and Y.Z. K.W. and T.T. grew the bulk hBN crystals. J.S. and K.F.M. designed the scientific objectives and oversaw the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Qinghai Tan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Optical images of the devices.

a, b, Optical micrographs of MoTe2/WSe2 device 1 (a) and device 2 (b). The top gate (TG, black dashed line) and bottom gate (BG, blue dashed line) are outlined. The channel is defined by the overlap of the two gates. Scale bars, 5 µm. The separation between adjacent electrodes is about 2 µm for device 1 (a) and is about 1 µm for device 2 (b).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Determination of the quasiparticle effective mass in the W-layer.

a, b, Doping dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\left(T\right)-{R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\left(T=10\,{\rm{K}}\right)\) at \({B}_{\perp }=14\) T at varying temperatures for \(\nu =1+{\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (a) and \(\nu =0+{\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (b). Insets show the corresponding Dingle plots of the SdH amplitude (divided by T) versus T at selected fillings. The slope of the linear fit (solid line) yields the quasiparticle effective mass \({m}_{{\rm{c}}}^{* }\) of the W-layer. c, Filling-factor dependence of the extracted quasiparticle effective mass (in units of the free electron mass \({m}_{0}\)) for both \(\nu =1+{\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (blue) and \(\nu =0+{\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (black). Error bars denote the standard deviation from data fitting. (The results are from device 1.).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Kondo lattice physics at v = 1 + vc.

a, b, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) (a) and \({R}_{\mathrm{xy}}\) (b) as a function of \(\nu =1+{\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) and \({B}_{\perp }\) with νc varying along the arrow direction shown in Fig. 2a (\(T=1.6\) K). The dashed lines mark the critical field \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\) to fully polarize the iterant hole spins and the local moments. SdH oscillations emerge above \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), at which \({R}_{\mathrm{xy}}\) changes sign. c, d, Dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) (c) and the normalized Hall density \({n}_{{\rm{Hall}}}/{n}_{{\rm{M}}}\) (d) on \({B}_{\perp }\) at varying \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}=1\) (\(T=1.6\) K). The arrows in c denote the critical field \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\). Above \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), the Hall density in d reveals the carrier density of the decoupled W-band. (The results are from device 1.).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Temperature-induced Kondo breakdown at v = 1 + vc.

a, Temperature dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) at varying \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) along the arrow direction shown in Fig. 2a (\({B}_{\perp }=0\) T). The arrows mark the Kondo temperature \({T}^{* }\) (see Methods for its determination). The dashed line denotes the expected quantized value for a TI. b, Extracted \({T}^{* }\) (red), critical Zeeman energy \(g{\mu }_{{\rm{B}}}{B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}\) (black, estimated using g = 10) and coefficient A (blue) as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}=1\). Error bars denote the standard deviation from data fitting. c, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) versus \({T}^{2}\) at varying \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) in the Kondo lattice region (\({B}_{\perp }=0\) T). The solid lines show the linear fits to the low-temperature part of the data using \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}={R}_{0}+A{T}^{2}\), from which \(A\) was extracted. d, \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) versus \(T\) at varying \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) (same as in a), illustrating the determination of \({T}^{* }\). (The results are from device 1.).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Nonlocal measurements at v = 2.

a, b, Additional nonlocal measurements in the TKI (a) and mixed-valence (b) regimes. Left: \({R}_{{ij},{kl}}\) at 1.6 K as a function of \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) measured with source and drain electrode (k, l) and voltage probe pair (i, j). The dashed lines denote the expected quantized values. Right: schematic measurement configurations. Although the resistance values in the mixed-valence regime are not quantized, they scale consistently with each other. (The results are from device 2.).

Extended Data Fig. 6 In-plane magnetoconductance at v = 1 + 1.

a, In-plane magnetoconductance \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}(0\,{\rm{T}})/{R}_{\mathrm{xx}}({B}_{\parallel })\) at varying temperatures. Suppression is observed up to about 20 K. b, Nonlocal resistance \({R}_{\mathrm{64,91}}\) as a function of \({B}_{\parallel }\) in the TKI state. \({R}_{\mathrm{64,91}}\) is measured with source and drain electrode (9, 1) and voltage probe pair (6, 4). c, d, Schematic of the band structure and spin texture of the helical edge states under zero and finite \({B}_{\parallel }\) for the \(\Gamma\)-point (a) and K-point (b) quantum spin Hall insulators. In the \(\Gamma\)-point system (for example, HgTe, InAs/GaSb quantum wells and monolayer Td-WTe2), an in-plane magnetic field mixes spin-up and spin-down channels, opening a hybridization gap at the Dirac point. In the K-point system (for example, transition metal dichalcogenide moiré materials), an in-plane magnetic field partially mixes spins and induces a weak in-plane component due to Ising spin protection. (The results in a, b are from devices 1 and 2, respectively.).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Main results from device 2.

a, b, Local longitudinal resistance \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) at \(T=1.6\) K as a function of \(\nu\) and \(E\) at \({B}_{\perp }=0\) T (a) and 14 T (b). Holes are shared in both layers inside the region bounded by the orange dashed lines. The Kondo lattice regime is bounded by the blue lines. c, d, Dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) (c) and normalized Hall density \({n}_{{\rm{Hall}}}/{n}_{{\rm{M}}}\) (d) on \({B}_{\perp }\) at varying \({\nu }_{{\rm{c}}}\) with \({\nu }_{{\rm{f}}}=1\) (\(T=1.6\) K). Arrows in c denote the critical field \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\). Above \({B}_{\perp {\rm{C}}}\), the Hall density in d reveals the carrier density of the decoupled W-band. e, Local or bulk resistance as a function of temperature. The dashed line denotes the expected quantized value. f, Magnetic-field dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}(0\,{\rm{T}})/{R}_{\mathrm{xx}}(B)\) at 1.6 K. Strong magnetoresistance is observed only for the TKI under an in-plane field.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Gap size at v = 2.

a, Normalized penetration capacitance \({C}_{{\rm{p}}}/{C}_{{\rm{series}}}\) as a function of \(\nu\) and \(E\) at \(T=1.6\) K and \({B}_{\perp }=0\) T. The Kondo lattice regime is marked by the blue dashed line. An incompressible state is observed at \(\nu =2\). b, Electric-field dependence of the thermodynamic gap size \(\varDelta\) at \(\nu =2\), obtained by integrating the normalized penetration capacitance \({C}_{{\rm{p}}}/{C}_{{\rm{series}}}\) (see Methods). c, Electric-field dependence of the estimated thermal activation gap from the temperature dependence of \({R}_{{\rm{bulk}}}\). Error bars denote the standard deviation from data fitting. The dashed lines in b, c indicate the phase boundaries (\({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\), see main text) separating three regimes: a band insulator, mixed-valence insulator and TKI. d, Arrhenius fits (solid lines) for the temperature dependence of \({R}_{{\rm{bulk}}}\) at two representative electric fields (\(E=0.63\,{\rm{V}}/{\rm{nm}}\) and \(E=0.75\,{\rm{V}}/{\rm{nm}}\)). (The results in a, b, and c, d are from devices 1 and 2, respectively.).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Kondo-lattice to mixed-valence crossover at v = 2.

a, Electric-field dependence of \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) at varying temperatures (\({B}_{\perp }=0\) T) at \(\nu =2\). The dashed lines indicate the phase boundaries (\({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\), see main text) separating three regimes: a band insulator, mixed-valence insulator and TKI. b, In-plane (solid) and out-of-plane (dashed) magnetoconductance \({R}_{\mathrm{xx}}(0\,{\rm{T}})/{R}_{\mathrm{xx}}(B)\) in the TKI (filled symbols) and mixed-valence (empty symbols) regimes at \(\nu =2\) (\(T=1.6\) K). (The results are from device 1.).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Luttinger-liquid behavior of the mixed-valence insulator.

a, b Scaled differential conductance \({G}_{\mathrm{xx}}\equiv ({dI}/{dV})/{T}^{\alpha }\) as a function of \(e{V}_{{\rm{dc}}}/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\) (where \({V}_{{\rm{dc}}}\) is the measured dc value of \({V}_{\mathrm{xx}}\) in Fig. 1e) at varying temperatures in the mixed-valence (a) and TKI (b) regimes at \(\nu =2\). In a, all data collapse into a single curve, consistent with the Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid theory, which describes the universal behavior of one-dimensional interacting fermions. In b, the edge conductance shows a negligible dependence on bias voltage. (The results are from device 1.).

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Z., Xia, Y., Xia, Z. et al. Topological Kondo insulator in MoTe2/WSe2 moiré bilayers. Nat. Phys. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-026-03170-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-026-03170-1