Abstract

Solids subjected to repeated cycles of stress or deformation can fail after several cycles, a phenomenon termed fatigue failure. Although intensely investigated for a wide range of materials owing to its obvious practical importance, a microscopic understanding of the initiation of fatigue failure continues to be actively pursued, in particular for soft and amorphous materials. Employing computer simulations, here we show that upon approaching the so-called fatigue limit, the failure times of glasses subjected to cyclic shear deformation display a power-law divergence, which is at variance with commonly used functional forms, and exhibit a strong dependence on the degree of annealing of the glasses. Our simulations explore measures of damage based on a quantification of plastic rearrangements and on energy dissipated. The fraction of particles that undergo plastic rearrangements and the percolation transition they undergo are both predictive of failure. We also find a robust power law between the accumulated damage, which is quantified by the energy dissipated or the non-affine displacements, and the failure times, which permits prediction of failure times based on the behaviour in the initial cycles. These observations reveal salient new microscopic features of fatigue failure and indicate approaches for developing a full microscopic picture of fatigue failure in amorphous solids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The mechanical response of a solid to applied stress or deformation is a material property of obvious importance. This response for large enough applied stresses involves plastic rearrangements and eventually leads to yielding and failure. Of particular importance is fatigue failure, wherein a solid, subjected to repeated cycles of stress or deformation, eventually fails1,2. The number of cycles to failure, known as the failure time, increases upon a reduction of the stress or deformation towards a threshold value termed the fatigue or endurance limit. Below the fatigue limit, a solid can be subjected to an indefinite number of cycles of loading without failing. Several empirical forms have been used to describe the variation of failure times upon approaching the fatigue limit. Descriptions of fatigue failure, developed over decades for metallic, crystalline materials, are expressed in terms of the formation and growth of microcracks3 and, correspondingly, the accumulation of damage, which is quantified by several measurable properties4,5,6. The initiation of failure at the microscopic level occurs before macroscopic signatures are detectable but is essential to understand when developing a theoretical explanation of the fatigue failure process. The characterization of such initiation, especially for soft and amorphous solids, is elusive5,6,7,8,9,10 and is closely related to an understanding of yielding and the creep behaviour in these materials. The disorder inherent to amorphous materials and the corresponding heterogeneity of response exhibit a rich diversity and pose challenges to understanding their mechanical response, which have been investigated actively in recent years11,12,13,14.

In particular, theoretical and computational investigations of yielding behaviour under cyclic shear deformation have been actively pursued recently15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Upon cyclic shear, with increasing applied strain amplitude, glasses undergo a transition (in the steady states reached after repeated cyclic deformation) from non-diffusive to diffusive changes in particle (cycle-to-cycle) positions15,16,18,19,20,21,22 with shear banding above the transition. The nature of the transition also displays a striking dependence on the degree of annealing of the glasses, with a qualitative change in behaviour across a threshold degree of annealing, which intriguingly seems to be related to the mode coupling crossover of glassy dynamics22. The number of cycles needed to reach a steady state seems to diverge as the transition point is approached from either side. The dependence on the distance from the transition (which we identify as the fatigue limit) of the number of cycles to failure is an important characteristic of fatigue failure, which we investigate in detail for a model glass in the present work.

We perform simulations of cyclic shear at a constant shear rate and at a very low temperature for a large number of samples of different classes of glasses, for different system sizes, for a wide range of degrees of annealing and for a range of shear deformation amplitudes, including amplitudes for which the glasses exhibit failure. The details of the simulations are provided in Methods and in Supplementary Information. Our results show that failure times diverge in a power-law fashion at the fatigue limit and show a strong dependence on the degree of annealing of the glasses. We explore the relation between different cumulative measures of plasticity and find striking correlations with failure times. Particles undergoing plastic rearrangements accumulate in a spatially heterogeneous manner, reach a nearly fixed fraction at the time of failure and percolate as a precursor to shear band formation. The dissipation of the accumulated energy, as an alternative measure of plasticity, exhibits a power-law relation with failure times. The near constancy of energy dissipation per cycle permits prediction of failure times from the energy dissipated in the initial cycles. We present these results below and close with a discussion of their implications.

Identification of the yield strain amplitude and fatigue limit

Previous work has shown that upon application of repeated cycles of strain, glasses approach limits states wherein the cycle-to-cycle displacements of particles either vanish (for small strain amplitude \({\gamma }_{\max }\)) or reach finite steady-state values (for large enough strain \({\gamma }_{\max } > {\gamma }_{\max }^{{\rm{Y}}}\), \({\gamma }_{\max }^{{\rm{Y}}}\) being the yield strain amplitude) and exhibit diffusive behaviour15,19. We use the average per cycle displacements of particles (Δr) or equivalently the mean squared displacements to identify the yield strain \({\gamma }_{\max }^{{\rm{Y}}}\), as shown in Supplementary Section 1.

Identification of failure events

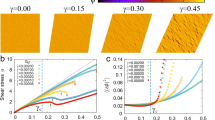

For \({\gamma }_{\max } > {\gamma }_{\max }^{{\rm{Y}}}\), the sheared glasses transition to a diffusive steady state after a finite number of strain cycles, which we refer to as the failure time tf (we use the number of cycles ncyc as the time variable, and refer to it interchangeably as time, t). To identify the failure time, we monitor the per particle potential energy U/N, the structural change through the bond-orientational order parameter q6 (ref. 30) and the plasticity using the per particle non-affine displacement \({D}_{\min }^{2}\) (ref. 31) from the previous cycle to the present. Details of the calculation of these metrics are given in Methods. As shown in Fig. 1a for a well-annealed sample, U/N changes sharply when the system fails (a similar sharp change is also observed for q6 and \({D}_{\min }^{2}\)). The failure time tf is estimated to be the midpoint of the transformation, based on a fit to a sigmoid function (Supplementary Section 2). We define the failure initiation time tfi = tf − w/2, where the width w is the time interval over which the transformation happens. Further details regarding the fitting procedure and illustrative results for several samples using different metrics across different strain amplitudes, different system sizes and different degrees of annealing are given in Supplementary Section 2.

a, Potential energy per particle U/N as a function of number of strain cycles ncyc for \({\gamma }_{\max }=0.068\) and N = 64,000 for the KA-BMLJ system. The solid line is a fit to a sigmoid function, whose inflection point is identified as the failure time (tf = 1,361 for the case shown), as indicated by the vertical dashed red line. Dotted vertical lines indicate the width w of the time interval over which failure occurs, along with the time of initiation of failure tfi = tf − w/2. Inset: a snapshot of the system after failure at ncyc = 1,670 (marked by the cross in the main panel). b–d, Sample-averaged failure times 〈tf〉 as a function of \({\gamma }_{\max }-{\gamma }_{\max }^{{\rm{Y}}}\) exhibit a power-law divergence with exponent −2 for different system sizes for three different degrees of annealing of the KA-BMLJ model: inherent structure energy eIS = −6.96 (parent temperature Tp = 0.5) (b), eIS = −7.00 (Tp = 0.435) (c) and eIS = −7.05 (Tp = 0.373) (d). e,f, Failure time divergence for the CP model (e) and BKS silica (f) for well-annealed cases. The yield strain amplitudes for different models, degrees of annealing and system sizes are indicated in the legends. Lines indicate the power law with exponent −2.

Strain amplitude dependence of failure time

We study the dependence of the sample-averaged failure time 〈tf〉 on the strain amplitude \({\gamma }_{\max }\). Several forms of the dependence of the fatigue failure times under different loading conditions and settings are discussed in the literature1,5,7,32, not all of which correspond to a divergence of the failure time, notwithstanding the possibility of a fatigue limit. We find that the failure time tf does indeed diverge in a power-law fashion as the yield strain amplitude \({\gamma }_{\max }^{{\rm{Y}}}\) is approached from above. As shown in Fig. 1b, the failure times (obtained here from energy evolution; results obtained from other metrics are shown in Supplementary Section 2) can be described well by the diverging power-law behaviour, with a divergence exponent −2:

The robustness of this power law is verified across three different system sizes and different degrees of annealing, as shown in Fig. 1b–d. We further demonstrate that the same exponent holds for other types of glasses as well by investigating two models of silica (a different class of glass with an open network structure), Coslovish–Pastore (CP) model and van Beest–Kramer–van Santen (BKS) model (from athermal quasistatic shear simulations), as shown in Fig. 1e,f, respectively.

The apparent power-law divergence of the number of cycles needed to reach a steady state has previously been observed in simulations15,16,19,29,33 and theoretical estimates27 but with various estimates for the exponent16,29,33. The estimated exponent value reported here is more reliable, we believe, given the substantially better sampling and given the robustness with respect to the estimated yield strain amplitude (Supplementary Section 4), system size and degree of annealing. We confirm these results by estimating the mean failure times from sample-to-sample fluctuations of energy34, as shown in Supplementary Information Section 5. Although recent theoretical work has addressed fatigue failure27,35,36,37 and creep38,39, the exponents predicted for the power-law divergence of failure times (−1 for poorly annealed glasses36, also observed in a simulated elastoplastic model37, and −1/2 for well-annealed glasses27,36) do not agree with those seen in simulations. The origins of this discrepancy need to be investigated in future work.

Dependence of failure time on the degree of annealing

The nature of the yielding transition strongly depends on the degree of annealing of the glass19,22,23,27,40, which prompts us to investigate how the degree of annealing influences the failure times. Even though the power-law exponent for the divergence of failure times is the same for the two cases of annealing described above, the failure time at a given strain amplitude increases with increasing annealing. We, thus, consider glasses obtained from a wide range of parent temperatures Tp (Methods) that straddle the Tp corresponding to the threshold degree of annealing previously identified22, the mode coupling temperature TMCT. For a fixed strain amplitude \({\gamma }_{\max }=0.1\), the cycle-dependent evolution energy for a single sample and sample-averaged energy for different degrees of annealing is shown in Fig. 2a,b, respectively. The failure times tf extracted as described earlier exhibit an Arrhenius dependence on Tp for moderate annealing (higher Tp), like observations in ref. 28 for an elastoplastic model, as shown in Fig. 2c. However, the dependence becomes super-Arrhenius at low Tp. Interestingly, the crossover occurs around Tp = TMCT. For Tp < TMCT, the yield strain \({\gamma }_{\max }^{Y}\) increases rapidly, making the distance to the yield point smaller for a fixed \({\gamma }_{\max }\), which appears to cause the super-Arrhenius increase of tf. The origin and implications of this crossover degree of annealing (discussed in ref. 22) need to be further investigated.

a,b, Potential energy U/N versus number of cycles ncyc for N = 4,000 and \({\gamma }_{\max }=0.1\) for different degrees of annealing, expressed in terms of initial inherent structure energy eIS for a single sample (a) and sample-averaged data (b). Solid lines are fits with a sigmoid function. a and b have the same colour code. c, Blue circles represent \({T}_{{\rm{p}}}{\rm{ln}}({t}_{{\rm{f}}})\) and green squares represent \({\rm{ln}}({t}_{{\rm{f}}})\), with the corresponding y axes on the left and right, respectively. The dashed vertical magenta line denotes Tp = TMCT. The solid horizontal blue line is a guide to the eye and represents a constant value of \({T}_{{\rm{p}}}{\rm{ln}}({t}_{{\rm{f}}})\) across different values of Tp above TMCT. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. See Supplementary Section 2 for details. Below the mode coupling temperature TMCT = 0.435, tf increases in a super-Arrhenius fashion with decreasing Tp.

We also compute the distribution of failure times, whose analysis will be pursued elsewhere. Finally, we also investigate the width (in cycles) of the failure event and present the results in Supplementary Section 6.

Mechanism of failure

Having characterized the behaviour of failure times, we next focus on possible ways to comprehend the systematic variation as well as the variability of failure times. A notion that has often been discussed in this context is that of damage accumulation1,4,5,6,7,32,41,42, which is meant to encapsulate irreversible changes in a solid that eventually lead to failure. However, what property can actually be termed as damage for an amorphous system and how such accumulated damage may account for failure and failure times are not entirely clear, although the extent of plastic activity is an obvious quantity to consider as a quantifier of damage, and several works (for example, refs. 4,5) have considered dissipated work as another. We consider now the correlation of failure times and quantifications of plasticity and dissipated work, computing them up to the failure initiation time tfi = tf − w/2. Accumulating quantities up to tf rather than tfi (the latter being a less ambiguous choice) affects some details of the results, but the overall picture remains unchanged, as shown in Supplementary Section 7.

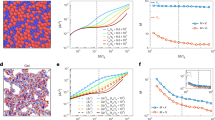

Plastic rearrangements

Non-affine displacements have been extensively used for studying plastic rearrangements in glasses. We first compute the non-affine displacement between the initial configuration and the configuration after ncyc cycles of shear, \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}\). The evolution of \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}\) with ncyc is shown in Fig. 3a(i) and the energy U/N in Fig. 3a(ii), both of which show a rapid rise across the failure time tf. Although enhanced plasticity upon failure is not surprising, we wish to know if the accumulated plastic activity leading up to failure bears any correlation with failure times. To this end, we plot in Fig. 3b the accumulated plasticity until the failure initiation time, quantified by \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}({t}_{\mathrm{fi}})\), as a function of the failure initiation time tfi for a range of strain amplitudes. Notably, the data for each case broadly fall on the same master curve, which is described well by a power law with exponent 0.4. Results for poorly annealed, deeply annealed ultra-stable and network-forming silica glasses are very similar, as shown in Supplementary Sections 8, 10 and 12.

a, Non-affine displacements are used to quantify the plasticity and correlations with failure times. The non-affine displacement with respect to the initial configuration \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}\), averaged over particles for a single sample, is shown in (i), and the corresponding variation of the energy per particle U/N is shown in (ii), both as functions of the number of cycles ncyc for several \({\gamma }_{\max }\). The failure times are indicated with vertical dotted lines across which both the quantities increase sharply. b, Accumulated damage until failure initiation, \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}({t}_{\mathrm{fi}})\), as a function of the failure initiation time tfi for different \({\gamma }_{\max }\). The solid line is a fit to a power law with exponent 0.4. c, Distribution of cycle-to-cycle non-affine displacement \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}\equiv {D}_{\min }^{2}(\Delta t=10\,\mathrm{cycles})\), computed at different numbers of cycles of strain. A threshold of \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}=1.2\) is chosen beyond which the particles are identified as mobile particles. d, Accumulation of mobile particles (for \({\gamma }_{\max }=0.069\)) along the gradient (y) direction, showing that plasticity accumulates in a spatially heterogeneous way well before failure and is concentrated around the eventual location of the shear band that forms at failure. e, Total number of mobile particles accumulated up to the failure initiation time tfi plotted against tfi for runs starting with different configurations and different \({\gamma }_{\max }\). e has the same colour code as b. The fraction of mobile particles reaches a nearly constant value at failure as tfi varies over more than two orders of magnitude. f, The cycle at which instantaneous or accumulated mobile particles percolate in one or two directions of the system, compared with the failure time (tf), showing that percolation occurs close to the time of failure for instantaneous mobile particles and before tf for accumulated mobile particles. Data points for each case were collected for different samples across several \({\gamma }_{\max }\). The solid line through the data points corresponds to tperco = tf as a guide to the eye. All data presented here are for N = 64,000 and eIS = −7.00 (Tp = 0.435). 1D, one-dimensional; 2D, two-dimensional.

Although the accumulated damage as measured by \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}\) does not reach a constant value at failure, as previously argued in other cases4,5, the power law observed across several different samples and strain amplitudes indicates a close relation. As \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}\) contains contributions from plastic activity (however, potentially occurring several times in the same regions in space before failure) and non-affine displacements that may arise away from the centres of plastic activity, we consider a different measure that seeks to quantify the fraction of a sample in which plastic activity has taken place. Thus, we calculate damage as the accumulation of mobile particles that undergo plastic rearrangements. Mobile particles are identified through cycle-to-cycle non-affine displacements. In practice we compute \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}\) between two stroboscopic configurations that are ten cycles apart. The distribution of \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}\) for a given amplitude \({\gamma }_{\max }=0.069\) and for different numbers of strain cycles ncyc is shown in Fig. 3c for a sample with tf ≈ 1,322. The distributions exhibit power-law behaviour, followed by a cutoff, when ncyc is small. For large ncyc, beyond the failure time tf ≈ 1,322, substantial deviations are apparent beyond \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}\approx 1.0\), stemming from very high plastic activity after failure.

As in past work, for example, refs. 19,43, it is necessary to employ a cutoff to identify mobile particles, in the absence, however, of a clear bimodality. We consider cutoffs in the range 0.5 to 2.0, which provide consistent but numerically different results depending on the choice (note that the nearest-neighbour separation distances at the first minima of the radial distribution functions are \({r}_{\min }^{\mathrm{AA}}=1.42\), \({r}_{\min }^{\mathrm{AB}}=1.26\) and \({r}_{\min }^{\mathrm{BB}}=1.1\)). There is a need to develop better methods of detecting and quantifying, let alone predicting44, plasticity. Recent work investigating localized modes and topological characterization are promising directions but need further elaboration45,46,47,48.

Results are shown in Fig. 3d–f for a cutoff \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}=1.2\). Particles with \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}\) greater than the cutoff are labelled as mobile particles, and we consider the cumulative set of mobile particles as a function of the number of cycles. To understand the manner in which plastic activity may cumulatively lead to failure, we consider the fraction of particles that are mobile in slabs indexed by their position y along the gradient direction. Figure 3d shows the fraction of mobile particles \({n}_{\mathrm{Mobile}}^{(\mathrm{slab})}\) versus y for different numbers of cycles. Although the cycle-to-cycle activity shows no clear spatial pattern before failure, strikingly, we see that there is a heterogeneous accumulation of plastic activity around the eventual position of shear band formation upon failure (shifted to be centred at y = 0 for visualization), well before failure occurs. We consider next the fraction of particles in the entire system nMobile, up to the failure initiation time tfi. This fraction is plotted against tfi in Fig. 3e, for several strain amplitudes and samples. Interestingly, nMobile(tfi) is independent of the failure time, as the glasses fail when a (nearly) fixed fraction of particles undergo plastic rearrangement!

Several works have considered the possible relation between yielding or failure and the percolation of regions of plastic activity19,49,50,51,52,53, but the results so far could be characterized as tentative. In general, these investigations have studied uniform shear and have considered the percolation of particles that are mobile upon yielding or failure. For cyclically sheared glasses, it was shown in ref. 19 that particles that are mobile above the yielding point percolate but do so discontinuously. In the present context, what is of interest is to know whether the percolation of accumulated plasticity may act as a precursor to failure. We, thus, perform a percolation analysis for the accumulated mobile particles (as described in ref. 19) after different numbers of cycles. Figure 3f shows the time at which the percolation of accumulated mobile particles tperco occurs as a function of the failure time along with the time at which percolation occurs for particles that are mobile at a given cycle. The data clearly show that for all samples and strain amplitudes studied, the percolation of accumulated mobile particles closely tracks failure and precedes the percolation of the current subset of mobile particles. The latter observation clearly distinguishes the percolation observed previously19 upon failure from the percolation of activity that serves as a precursor to failure. Corresponding results for poorly annealed glasses, shown in Supplementary Section 8, indicate a poorer correlation.

To explore more robust methods for identifying mobile particles, we investigate the procedure recently proposed in ref. 54. The results described in Supplementary Section 9 indicate that both methods produce comparably satisfactory results but with limitations that emphasize the need for improved methods to identify regions of plasticity.

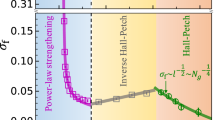

Dissipated work

As another measure of accumulated damage, we consider dissipated work, which has been studied in several previous works. We define the damage in each cycle Dcyc in terms of dissipated work in a mechanical system, that is the stress–strain loop area. The variation of Dcyc with strain cycle is shown in Fig. 4a. Before failure, Dcyc is small and nearly constant as the stress–strain curve encloses a small area, as shown in the left-hand inset of Fig. 4a. After a sufficient number of strain cycles, when the system fails, Dcyc increases suddenly owing to the enhanced plasticity in the yielded system, and the stress–strain curve encloses a large loop area (right-hand inset). Figure 4b shows the evolution of accumulated damage until a cycle t, defined as \({D}^{\mathrm{acc}}(t)={\sum }_{t{\prime} =1}^{t}{D}^{\mathrm{cyc}}(t{\prime} )\). For each sample, we collected the accumulated damage until the failure initiation time \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}={D}^{\mathrm{acc}}(t={t}_{\mathrm{fi}})\), which are shown for well-annealed and poorly annealed systems in Fig. 4c,d, respectively. We find \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}\) increases with tfi following a power-law scaling behaviour:

where β = 0.8, which was found to be the same for well-annealed and poorly annealed glasses. Importantly, as the exponent is non-zero, there is a positive correlation between \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}\) and tfi, and so there is no level of critical damage that a system needs to achieve before it fails.

a, Damage in each cycle Dcyc, defined as the stress (σ) versus strain (γ) loop area, as a function of strain cycle ncyc. Insets: stress–strain loops at two different cycles across the failure. b, Accumulated damage Dacc against ncyc for different \({\gamma }_{\max }\). The solid line for a representative \({\gamma }_{\max }\) indicates that Dacc increases roughly linearly with ncyc until the failure initiation time tfi. The crosses indicate the failure initiation time tfi. The dashed line shows that the accumulated damage until the failure initiation time \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}=A{t}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{0.8}\). c,d, \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}\) grows with tfi with a power of 0.8 for two different degrees of annealing: eIS = − 7.00 (Tp = 0.435) (c) and eIS = −6.96 (Tp = 0.5) (d). Symbols with the same colour indicate sample-to-sample data for a given \({\gamma }_{\max }\). e, Failure initiation time tfi versus average damage per cycle \(\langle {D}_{{\rm{fi}}}^{\mathrm{cyc}}\rangle\) (computed up to tfi) fitted as a power law for a subset (50%) of samples to estimate the parameter A = 0.036 for eIS = −7.00. f, Predicted failure initiation time \({t}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{pred}}\) based on the estimated value of parameter A compared with the observed times \({t}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{real}}\) (for the remaining 50% of samples) for different \({\gamma }_{\max }\).

Nevertheless, the striking power law we observe in Fig. 4c,d, between \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}\) and tfi, together with the nearly linear increase of Dacc observed in Fig. 4b, permits the prediction of failure times from the behaviour of the damage in the initial cycles, as we now demonstrate. (In passing, we note that whereas Dacc(t) ∝ t, \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}(t)\propto {t}^{1/2}\) before failure, and thus, we expect \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{init}}({t}_{\mathrm{fi}})\propto {D}^{\mathrm{acc}}{({t}_{\mathrm{fi}})}^{1/2}\propto {t}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\beta /2}\), which we indeed observe.) First, Fig. 4c,d permits the evaluation of the (annealing-dependent) prefactor in \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}=A{t}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\beta }\). A detailed discussion of how the prefactor varies with the degree of annealing is provided in Supplementary Section 11. Knowing the prefactor A, the failure time can be predicted from the cycle-dependent value of Dacc. Assuming that the damage per cycle 〈Dcyc〉 is nearly constant until failure, we have \(\langle {D}^{\mathrm{cyc}}\rangle =A{t}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\beta -1}\), so that we can predict tfi from the observed 〈Dcyc〉 in the initial cycles. To verify this, first, we took half of the samples from our whole ensemble that failed at different times across different \({\gamma }_{\max }\). We computed the slope of the accumulated damage against ncyc up to the failure initiation time tfi of these training samples. As shown in Fig. 4e, we found that tfi decreases with the rate of accumulated damage \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{cyc}}\) (computed up to tfi) as

with A ≈ 0.036 and \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=5\). Note that the value of \({\beta }^{{\prime} }=1/(1-\beta )\) is in excellent agreement with independent measure of β from the analysis of \({D}_{\mathrm{fi}}^{\mathrm{acc}}\). After determing the prefactor from the training samples, we then tested the other half of the samples to predict tfi. For each test sample, we computed the rate of accumulated damage \({D}_{n}^{\mathrm{cyc}}\) for the first n cycles and predicted the failure initiation time from equation (3). The data presented in Fig. 4f for n = 20 show that the predicted failure initiation times are in excellent agreement with the actual values. (Results for other annealing cases and for silica are shown in Supplementary Sections 8, 10 and 12.)

Strikingly, our analysis demonstrates that the failure time of a sample can be predicted using information from only the first few strain cycles, an observation that could be useful in predicting the failure time of actual materials.

Conclusions

In summary, we studied fatigue failure in different classes of glass subject to a finite rate of cyclic shear. Failure is identified through a sigmoidal and rapid change in energy, measures of structural change and plasticity. The number of cycles to failure, calculated from these metrics, shows a power-law dependence on the distance from the yield strain amplitude from above, with a power-law exponent of −2. The exponent is robust across different degrees of annealing, different system sizes and the types of glasses we investigated. For a constant strain amplitude, the failure time increased as we increased the degree of annealing, with an initial Arrhenius dependence on the parent temperature, followed by a super-Arrhenius dependence at low parent temperatures. The crossover corresponds to the threshold degree of annealing identified earlier, across which the nature of yielding changed qualitatively.

Finally, we investigated whether damage accumulated over cycles is related to failure. Using two metrics based on plasticity and dissipated energy, we found striking relations between accumulated damage and failure times. We found that failure occurs when the accumulated subset of (mobile) particles that have undergone plastic rearrangement reaches a fixed fraction, for which we observed the percolation of such accumulated particles. Considering dissipated energy as the measure of damage, although we found no critical level of damage at which failure occurs, we found a robust power law between energy dissipated until failure and the failure time. Such a relation permits a prediction of failure times based on the response of the solid to the initial cycles of shear.

Together, these results present an appealing picture of how accumulated damage leads to fatigue failure. These results should also contribute considerably in developing a full-fledged elastoplastic model microscopic picture and a theoretical explanation of fatigue failure in amorphous solids.

Methods

Models and simulation details

KA-BMLJ model

We simulated the three-dimensional 80:20 Kob–Anderson binary mixture of Lennard–Jones particles (KA-BMLJ model) interacting via the potential19

where α, β ∈ {A, B} are particle types with the parameters ϵAB/ϵAA = 1.5, ϵBB/ϵAA = 0.5, σAB/σAA = 0.8, σBB/σAA = 0.88 and rc,αβ = 2.5σαβ. Here c0αβ and c2αβ are chosen such that both the potential and the force go to zero at rc,αβ: \({c}_{0\alpha \beta }=-7{(\frac{{\sigma }_{\alpha \beta }}{{r}_{c,\alpha \beta }})}^{12}+4{(\frac{{\sigma }_{\alpha \beta }}{{r}_{c,\alpha \beta }})}^{6}\) and \({c}_{2\alpha \beta }=6{(\frac{{\sigma }_{\alpha \beta }}{{r}_{c,\alpha \beta }})}^{14}-3{(\frac{{\sigma }_{\alpha \beta }}{{r}_{c,\alpha \beta }})}^{8}\). The units of length, energy and time were chosen to be σAA, ϵAA and \(\sqrt{\frac{{\sigma }_{\mathrm{AA}}^{2}}{{\epsilon }_{\mathrm{AA}}}}\), respectively. We use an integration time step of 0.005 for equilibration.

BKS silica model

We simulated the BKS potential55 of silica in three dimensions, with modifications56, given by

where α, β ∈ {Si, O}, and the short-range term \({\phi }_{\alpha \beta }(r)\)\(=4{\epsilon }_{\alpha \beta }\left[{\left({\sigma }_{\alpha \beta }/r\right)}^{30}\right.\)\(\left.-{\left({\sigma }_{\alpha \beta }/r\right)}^{6}\right]\) is added to prevent the divergence of the Coulomb interaction. We applied an Ewald summation to evaluate the Coulomb term. All the parameter values are the same as in ref. 22.

CP model

We also consider a three-dimensional binary mixture of a short-range model with network-forming ability, namely the CP model57. The interaction potential between particle type α, β ∈ {A, B} is given by

for r < rc,αβ and zero otherwise (δαβ is the Kronecker delta). The term Us,αβ(r), which has a quadratic dependence on r, was chosen based on the conditions that the potential and its derivative at rc,αβ must vanish at the cutoff. All the parameter values are the same as in ref. 57. As in the KA-BMLJ model, we use reduced units for this model.

Initial glass preparation

We performed constant volume and temperature molecular dynamics simulations using the Nosé–Hoover thermostat. For the KA-BMLJ, we chose a wide range of parent temperatures Tp ∈ [0.435, 1] and reduced density 1.2. For BKS silica, we considered Tp = 2,500 K and ρ = 2.8 g cm−3. The corresponding choice of CP model has TP = 0.36 and ρ = 1.93. Configurations sampled from equilibrated trajectories underwent local energy minimization so that we could obtain the so-called inherent structures, which we employed as the glass configurations at zero temperature. Lower parent temperatures correspond to better annealed glasses. The energies of the inherent structures of the KA-BMLJ model corresponding to the range Tp ∈ [0.435, 1] are eIS ∈ [−7.00, −6.89].

We obtained the lower energy inherent structures for the KA-BMLJ model (those with eIS < −7.00 or Tp < 0.435) using mechanical annealing, a method reported in ref. 58. Glasses obtained through both constant volume and temperature molecular dynamics simulations and mechanical annealing exhibit a range of properties that are indistinguishable. In particular, both sets of configurations exhibit negligible stress anisotropies, as shown in ref. 58. Most of the results for KA-BMLJ reported here are for eIS = −6.96, −7.00 or −7.05, which we refer to as poorly annealed, well-annealed and deeply annealed ultra-stable glasses, respectively22. The choice of TP for the BKS silica and for the CP model corresponds to a well-annealed case.

Cyclic shear simulations

We performed non-equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations to implement the strain-controlled cyclic shear at finite temperatures and strain rates for the KA-BMLJ and CP models. We solved the Nosé–Hoover thermostat SLLOD59 equations of motion:

Here, ri and pi are the coordinate and momentum of particle i, and Fi are the forces on particle i. The strain γxy of the system was varied as \({\gamma }_{xy}(t)={\gamma }_{\max }\sin (\omega t)\), where \({\gamma }_{\max }\) is the maximum strain amplitude of the cycles. The shear rate at the start of the cycles was taken to be \({\dot{\gamma }}_{xy}(t=0)={\gamma }_{\max }\omega =0.001\). We chose the thermostat temperature to be T = 0.001. For cyclic shear, we chose an integration time step of 0.01. The damping coefficient α(t) for the Nosé–Hoover thermostat is α(t) = pη(t)/Q, where pη is the momentum for thermostat coordinate η, which evolves as:

where Nf is the number of degrees of freedom and kB is the Boltzmann constant. Q is the mass of the thermostat, which is associated with thermostat relaxation time τ: Q = NfkBTτ2. We chose τ = 1.0.

For BKS silica, we applied an athermal quasistatic cyclic shear, as mentioned in ref. 22. This protocol involves two elementary steps: (1) affine deformation through a small strain increment dγ = 2 × 10−4 in the x–z plane and (2) energy minimization. On repeating this procedure, the strain γ varies cyclically as: \(0\to {\gamma }_{\max }\to 0\to -{\gamma }_{\max }\to 0\).

For KA-BMLJ with a small system of size N = 4,000, at least 60 independent samples were studied for each \({\gamma }_{\max }\) ranging from 0.05 to 0.14 and for eIS = −6.96 (Tp = 0.5) and eIS = −7.00 (Tp = 0.435). For a single strain amplitude \({\gamma }_{\max }=0.1\), 100 samples were studied for more degrees of annealing in the range −7.07 < eIS < −6.92 (equivalently, 0.351 < Tp < 0.66). For larger systems with N = 64,000 or N = 128,000, 32 samples were studied for each strain amplitude and each degree of annealing mentioned in the text.

For the BKS silica, we considered N = 5,832 and one or two samples for several values of \({\gamma }_{\max }\). For the CP model, we considered 16–32 samples for a system of size N = 46,656.

All the numerical simulations, including molecular dynamics, cyclic shear and energy minimization using the conjugate gradient algorithm, were performed using our in-house modified version of LAMMPS60.

Definition of metrics for identifying failure

To estimate the failure time, we considered various structural and mechanical properties of the system, namely the per particle potential energy (U/N), bond-orientational order parameter q6 and non-affine displacement \({D}_{\min }^{2}\). All these metrics are per particle quantities, and we report averages over all particles. In the following, we provide a detailed definition of them.

Bond-orientational order parameter

The bond-orientational order parameter ql is calculated following30:

where Ylm are spherical harmonics and Nb(i) is the number of neighbours of reference particle i. We considered l = 6. For the KA-BMLJ model, we computed the quantity for type A particles, where the neighbour distance was taken to be 1.42 and 1.26 for the AA and AB types of interactions, respectively. These cutoffs correspond to the first minima in the pair correlation function.

Non-affine displacement

The non-affine displacement \({D}_{\min }^{2}\) of a particle i from time t − Δt to t is calculated as31:

where the indices α and β denote spatial coordinates and the index j runs over the neighbouring atoms of the reference atom i. Here the neighbour of an atom is defined as a particle that is within a particular distance from the reference particle. For the KA-BMLJ and CP models, the distance was taken as the pairwise interaction cutoff rc,αβ. For BKS silica, the distance was taken to be 2.05 Å, the first coordination shell.

The local strain ϵαβ that minimizes \({D}_{\min }^{2}\) was calculated as

where

Identification of mobile particles

To identify plastically rearranged mobile particles, we computed the cycle-to-cycle non-affine displacement \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}\) of each particle between two stroboscopic configurations that are ten strain cycles apart. The distribution of \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}\) is a power law with an exponential tail. We set a cutoff at \({D}_{\min }^{2,\mathrm{cyc}}=1.2\), where the exponential tail begins, and considered particles beyond this threshold to be mobile particles. This is not yet a very robust procedure, as discussed in the main text, and there is a need for improved criteria.

Percolation analysis

We performed a percolation analysis of accumulated mobile particles19 up to a certain number of strain cycles for the KA-BMLJ model. In this analysis, we considered that two mobile particles belonged to the same cluster if they were within a distance of 1.4, the first coordination shell of the particles. We extracted the largest cluster \({S}_{\max }\) and checked whether it spans the system. To identify that, we replicated the simulation box three times in all spatial directions so that the replicated system had 27 copies of the original simulation box. We then computed the clusters for this new replicated system. The largest cluster in the replicated system was 3, 9 or 27 times \({S}_{\max }\) of the original box if \({S}_{\max }\) in the original box percolates in one, two or three spatial directions, respectively.

Data availability

The dataset for this study is available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30945050 (ref. 61). Further data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

The minimal code needed to reproduce the data described in this article is available in the following repository: https://gitlab.com/sastry_lab/codes/fatiguefailuresimulation. Further code is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Suresh, S. Fatigue of Materials 2nd edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998).

Christensen, R. M. The Theory of Materials Failure 1st edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Weiss, J., Ben Rhouma, W., Deschanel, S. & Truskinovsky, L. Plastic intermittency during cyclic loading: from dislocation patterning to microcrack initiation. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 023603 (2019).

Naderi, M., Amiri, M. & Khonsari, M. M. On the thermodynamic entropy of fatigue fracture. Proc. R. Soc. A 466, 423–438 (2010).

Bhowmik, B. P., Hentchel, H. G. E. & Procaccia, I. Fatigue and collapse of cyclically bent strip of amorphous solid. Europhys. Lett. 137, 46002 (2022).

Bhowmik, B. P., Hentschel, H. G. E. & Procaccia, I. Scaling theory for Wöhler plots in amorphous solids under cyclic forcing. Phys. Rev. E 105, 015001 (2022).

Kun, F. et al. Fatigue failure of disordered materials. J. Stat. Mech. 2007, P02003 (2007).

Leocmach, M., Perge, C., Divoux, T. & Manneville, S. Creep and fracture of a protein gel under stress. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 038303 (2014).

Aime, S., Ramos, L. & Cipelletti, L. Microscopic dynamics and failure precursors of a gel under mechanical load. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 3587–3592 (2018).

Cipelletti, L., Martens, K. & Ramos, L. Microscopic precursors of failure in soft matter. Soft Matter 16, 82–93 (2020).

Bonn, D., Denn, M. M., Berthier, L., Divoux, T. & Manneville, S. Yield stress materials in soft condensed matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035005 (2017).

Nicolas, A., Ferrero, E. E., Martens, K. & Barrat, J.-L. Deformation and flow of amorphous solids: insights from elastoplastic models. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 045006 (2018).

Kumar, A. & Procaccia, I. Elasticity, plasticity and screening in amorphous solids: a short review. Europhys. Lett. 145, 26002 (2024).

Sollich, P. Challenges in the rheology of glasses. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.16409 (2024).

Fiocco, D., Foffi, G. & Sastry, S. Oscillatory athermal quasistatic deformation of a model glass. Phys. Rev. E 88, 020301 (2013).

Regev, I., Lookman, T. & Reichhardt, C. Onset of irreversibility and chaos in amorphous solids under periodic shear. Phys. Rev. E 88, 062401 (2013).

Priezjev, N. V. Heterogeneous relaxation dynamics in amorphous materials under cyclic loading. Phys. Rev. E 87, 052302 (2013).

Fiocco, D., Foffi, G. & Sastry, S. Memory effects in schematic models of glasses subjected to oscillatory deformation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27, 194130 (2015).

Leishangthem, P., Parmar, A. & Sastry, S. The yielding transition in amorphous solids under oscillatory shear deformation. Nat. Commun. 8, 14653 (2017).

Kawasaki, T. & Berthier, L. Macroscopic yielding in jammed solids is accompanied by a nonequilibrium first-order transition in particle trajectories. Phys. Rev. E 94, 022615 (2016).

Parmar, A. D. S., Kumar, S. & Sastry, S. Strain localization above the yielding point in cyclically deformed glasses. Phys. Rev. X 9, 021018 (2019).

Bhaumik, H., Foffi, G. & Sastry, S. The role of annealing in determining the yielding behavior of glasses under cyclic shear deformation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2100227118 (2021).

Yeh, W.-T., Ozawa, M., Miyazaki, K., Kawasaki, T. & Berthier, L. Glass stability changes the nature of yielding under oscillatory shear. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 225502 (2020).

Sastry, S. Models for the yielding behavior of amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 255501 (2021).

Mungan, M. & Sastry, S. Metastability as a mechanism for yielding in amorphous solids under cyclic shear. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 248002 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. The fate of shear-oscillated amorphous solids. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 104902 (2022).

Parley, J. T., Sastry, S. & Sollich, P. Mean-field theory of yielding under oscillatory shear. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 198001 (2022).

Cochran, J. O., Callaghan, G. L., Caven, M. J. G. & Fielding, S. M. Slow fatigue and highly delayed yielding via shear banding in oscillatory shear. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 168202 (2024).

Priezjev, N. V. Fatigue failure of amorphous alloys under cyclic shear deformation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 226, 112230 (2023).

Steinhardt, P. J., Nelson, D. R. & Ronchetti, M. Bond-orientational order in liquids and glasses. Phys. Rev. B 28, 784–805 (1983).

Falk, M. L. & Langer, J. S. Dynamics of viscoplastic deformation in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. E 57, 7192–7205 (1998).

Kun, F., Carmona, H. A., Andrade, J. S. & Herrmann, H. J. Universality behind Basquin’s law of fatigue. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 094301 (2008).

Kurotani, Y. & Tanaka, H. Fatigue fracture mechanism of amorphous materials from a density-based coarse-grained model. Commun. Mater. 3, 67 (2022).

Cabriolu, R., Horbach, J., Chaudhuri, P. & Martens, K. Precursors of fluidisation in the creep response of a soft glass. Soft Matter 15, 415–423 (2019).

Benzi, R. et al. Unified theoretical and experimental view on transient shear banding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 248001 (2019).

Sarkar, D. et al. Coarse grained descriptions of the dynamics of yielding of amorphous solids under cyclic shear. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2505.14912 (2025).

Khandare, P. & Sastry, S. Elastoplastic modelling of cyclic shear deformation of amorphous solids. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2602.06174 (2026).

Liu, C., Martens, K. & Barrat, J.-L. Mean-field scenario for the athermal creep dynamics of yield-stress fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 028004 (2018).

Popović, M., de Geus, T. W. J., Ji, W., Rosso, A. & Wyart, M. Scaling description of creep flow in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 208001 (2022).

Bhaumik, H., Foffi, G. & Sastry, S. Yielding transition of a two dimensional glass former under athermal cyclic shear deformation. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 064502 (2022).

Sethna, J. P. et al. Deformation of crystals: connections with statistical physics. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 47, 217–246 (2017).

Mangalath Shine, A. et al. Quantification of viscous and damage dissipation of bituminous binder and mastic using White–Metzner model. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 24, 2238112 (2023).

Bhaumik, H., Foffi, G. & Sastry, S. Avalanches, clusters, and structural change in cyclically sheared silica glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 098001 (2022).

Richard, D. et al. Predicting plasticity in disordered solids from structural indicators. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 113609 (2020).

Lerner, E. & Bouchbinder, E. Low-energy quasilocalized excitations in structural glasses. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 200901 (2021).

Baggioli, M., Kriuchevskyi, I., Sirk, T. W. & Zaccone, A. Plasticity in amorphous solids is mediated by topological defects in the displacement field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 015501 (2021).

Wu, Z. W., Chen, Y., Wang, W.-H., Kob, W. & Xu, L. Topology of vibrational modes predicts plastic events in glasses. Nat. Commun. 14, 2955 (2023).

Desmarchelier, P., Fajardo, S. & Falk, M. L. Topological characterization of rearrangements in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. E 109, L053002 (2024).

Dasgupta, R., Hentschel, H. G. E. & Procaccia, I. Microscopic mechanism of shear bands in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 255502 (2012).

Chikkadi, V. et al. Spreading plastic failure as a mechanism for the shear modulus reduction in amorphous solids. Europhys. Lett. 110, 48001 (2015).

Shrivastav, G. P., Chaudhuri, P. & Horbach, J. Yielding of glass under shear: a directed percolation transition precedes shear-band formation. Phys. Rev. E 94, 042605 (2016).

Ghosh, A. et al. Direct observation of percolation in the yielding transition of colloidal glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 148001 (2017).

Hieronymus-Schmidt, V., Rösner, H., Wilde, G. & Zaccone, A. Shear banding in metallic glasses described by alignments of Eshelby quadrupoles. Phys. Rev. B 95, 134111 (2017).

Barbot, A., Lerbinger, M., Lemaítre, A., Vandembroucq, D. & Patinet, S. Rejuvenation and shear banding in model amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. E 101, 033001 (2020).

van Beest, B. W. H., Kramer, G. J. & van Santen, R. A. Force fields for silicas and aluminophosphates based on ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1955–1958 (1990).

Saika-Voivod, I., Sciortino, F. & Poole, P. H. Free energy and configurational entropy of liquid silica: fragile-to-strong crossover and polyamorphism. Phys. Rev. E 69, 041503 (2004).

Coslovich, D. & Pastore, G. Dynamics and energy landscape in a tetrahedral network glass-former: direct comparison with models of fragile liquids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 285107 (2009).

Das, P., Parmar, A. D. S. & Sastry, S. Annealing glasses by cyclic shear deformation. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 044501 (2022).

Evans, D. J. & Morriss, G. P. Nonlinear-response theory for steady planar Couette flow. Phys. Rev. A 30, 1528–1530 (1984).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Maity, S. Data for figures of the article with title: ‘Fatigue failure in glasses under cyclic shear deformation’. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30945050 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Adhikari, V. Chikkadi, A. L. Greer, J. Horbach, P. Khandare, E. Lerner, I. Procaccia, D. Sarkar, P. Sollich, L. Truskinovsky and A. Zaconne for useful discussions and comments on the paper. We acknowledge the National Supercomputing Mission facility (Param Yukti) at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research for computational resources. H.B. acknowledges EPSRC for support (Grant No. EP/T031247/1) during a part of the period when this work was performed. S.S. acknowledges support from the Science and Engineering Research Board (Anusandhan National Research Foundation) (India) through the JC Bose Fellowship (Grant No. JBR/2020/000015) and a grant under Scientific and Useful Profound Research Advancement (SUPRA) (Grant No. SPR/2021/000382).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. conceived the research. S.M., H.B. and S.A. performed the research. S.M., H.B., S.A. and S.S. analysed the data. S.M., H.B. and S.S. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–12, including details of the procedure for estimating the yield strain amplitude; the method for computing the mean failure time and the error analysis of the estimated divergence exponent; the results on the duration of the failure process or the transformation width; the correlation between plasticity and failure time for a poorly annealed glass and a deeply annealed (ultra-stable) glass; measuring damage using an alternative approach to identify mobile particles and the generality of our results by investigating the network-forming glass, silica.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maity, S., Bhaumik, H., Athani, S. et al. Fatigue failure in glasses under cyclic shear deformation. Nat. Phys. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-026-03174-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-026-03174-x