Abstract

Extensive ecosystem restoration is increasingly seen as being central to conserving biodiversity1 and stabilizing the climate of the Earth2. Although ambitious national and global targets have been set, global priority areas that account for spatial variation in benefits and costs have yet to be identified. Here we develop and apply a multicriteria optimization approach that identifies priority areas for restoration across all terrestrial biomes, and estimates their benefits and costs. We find that restoring 15% of converted lands in priority areas could avoid 60% of expected extinctions while sequestering 299 gigatonnes of CO2—30% of the total CO2 increase in the atmosphere, or 14% of total emissions, since the Industrial Revolution. The inclusion of several biomes is key to achieving multiple benefits. Cost effectiveness can increase up to 13-fold when spatial allocation is optimized using our multicriteria approach, which highlights the importance of spatial planning. Our results confirm the vast potential contributions of restoration to addressing global challenges, while underscoring the necessity of pursuing these goals synergistically.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All input datasets are available from the references cited. All output datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

R codes developed for and used in this analysis are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Change history

30 August 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05178-y

References

IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES Secretariat, 2019).

IPCC. An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes In Terrestrial Ecosystems (SRCCL) (World Meteorological Organization, 2019).

Di Marco, M., Ferrier, S., Harwood, T. D., Hoskins, A. J. & Watson, J. E. M. Wilderness areas halve the extinction risk of terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 573, 582–585 (2019).

Maron, M., Simmonds, J. S. & Watson, J. E. M. Bold nature retention targets are essential for the global environment agenda. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1194–1195 (2018).

IPBES. The IPBES Assessment Report on Land Degradation and Restoration (IPBES Secretariat, 2018).

Bastin, J. F. et al. The global tree restoration potential. Science 365, 76–79 (2019).

Chazdon, R. & Brancalion, P. Restoring forests as a means to many ends. Science 365, 24–25 (2019).

Temperton, V. M. et al. Step back from the forest and step up to the Bonn challenge: how a broad ecological perspective can promote successful landscape restoration. Restor. Ecol. 27, 705–719 (2019).

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Strategic approaches to restoring ecosystems can triple conservation gains and halve costs. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 62–70 (2019).

Brancalion, P. H. S. et al. Global restoration opportunities in tropical rainforest landscapes. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav3223 (2019).

Mappin, B. et al. Restoration priorities to achieve the global protected area target. Conserv. Lett. 12, e12646 (2019).

Brooks, T. M. et al. Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 313, 58–61 (2006).

Joppa, L. N., Visconti, P., Jenkins, C. N. & Pimm, S. L. Achieving the convention on biological diversity’s goals for plant conservation. Science 341, 1100–1103 (2013).

Montesino Pouzols, F. et al. Global protected area expansion is compromised by projected land-use and parochialism. Nature 516, 383–386 (2014).

Ando, A., Camm, J., Polasky, S. & Solow, A. Species distributions, land values, and efficient conservation. Science 279, 2126–2128 (1998).

Naidoo, R. et al. Global mapping of ecosystem services and conservation priorities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9495–9500 (2008).

Beyer, H. L., Dujardin, Y., Watts, M. E. & Possingham, H. P. Solving conservation planning problems with integer linear programming. Ecol. Modell. 328, 14–22 (2016).

Cabeza, M. & Moilanen, A. Design of reserve networks and the persistence of biodiversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 242–248 (2001).

European Space Agency. Climate Change Initiative (ESA CCI). https://www.esa-landcover-cci.org/?q=node/158 (accessed May 2018).

Veldman, J. W. et al. Where tree planting and forest expansion are bad for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bioscience 65, 1011–1018 (2015).

Thomas, C. D. et al. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427, 145–148 (2004).

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Impacts of incentives to reduce emissions from deforestation on global species extinctions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 350–355 (2012).

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Moment of truth for the Cerrado hotspot. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0099 (2017).

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2019-3 http://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed 10 December 2019).

Brooks, T. M. et al. Measuring terrestrial area of habitat (AOH) and its utility for the IUCN Red List. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 977–986 (2019).

Erb, K.-H. et al. Unexpectedly large impact of forest management and grazing on global vegetation biomass. Nature 553, 73–76 (2018).

Sanderman, J., Hengl, T. & Fiske, G. J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9575–9580 (2017).

IPCC. in Global Warming of 1.5°C (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 3–24 (World Meteorological Organization, 2018).

Poorter, L. et al. Biomass resilience of Neotropical secondary forests. Nature 530, 211–214 (2016).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000).

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Increasing Agricultural Output While Avoiding Deforestation—A Case Study for Mato Grosso, Brazil (International Institute for Sustainability, 2012).

Latawiec, A. E., Strassburg, B. B. N., Brancalion, P. H. S., Rodrigues, R. R. & Gardner, T. Creating space for large-scale restoration in tropical agricultural landscapes. Front. Ecol. Environ. 13, 211–218 (2015).

Anderson, C. B. et al. Determining nature’s contributions to achieve the sustainable development goals. Sustain. Sci. 14, 543–547 (2019).

Martín-López, B. et al. Nature’s contributions to people in mountains: a review. PLoS ONE 14, e0217847 (2019).

Latawiec, A. E., Strassburg, B. B. N., Valentim, J. F., Ramos, F. & Alves-Pinto, H. N. Intensification of cattle ranching production systems: socioeconomic and environmental synergies and risks in Brazil. Animal 8, 1255–1263 (2014).

Newbold, T. et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45–50 (2015).

Balmford, A. et al. The environmental costs and benefits of high-yield farming. Nat. Sustain. 1, 477–485 (2018).

Garnett, T. et al. Sustainable intensification in agriculture: premises and policies. Science 341, 33–34 (2013).

Erb, K.-H. et al. Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation. Nat. Commun. 7, 11382 (2016).

Reyes-García, V. et al. The contributions of Indigenous Peoples and local communities to ecological restoration. Restor. Ecol. 27, 3–8 (2019).

Possingham, H. P., Bode, M. & Klein, C. J. Optimal conservation outcomes require both restoration and protection. PLoS Biol. 13, e1002052 (2015).

Beresford, A. et al. Minding the protection gap: estimates of species’ range sizes and holes in the protected area network. Anim. Conserv. 14, 114–116 (2011).

Rondinini, C. et al. Global habitat suitability models of terrestrial mammals. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 366, 2633–2641 (2011).

Di Marco, M. et al. Synergies and trade-offs in achieving global biodiversity targets. Conserv. Biol. 30, 189–195 (2016).

Betts, M. G. et al. Global forest loss disproportionately erodes biodiversity in intact landscapes. Nature 547, 441–444 (2017).

Venter, O. et al. Targeting global protected area expansion for imperiled biodiversity. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001891 (2014).

Joppa, L. N. et al. Filling in biodiversity threat gaps. Science 352, 416–418 (2016).

Knight, A. T., Cowling, R. M. & Campbell, B. M. An operational model for implementing conservation action. Conserv. Biol. 20, 408–419 (2006).

Ban, N. C. et al. A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: embedding social considerations. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 194–202 (2013).

Halpern, B. S. et al. Achieving the triple bottom line in the face of inherent trade-offs among social equity, economic return, and conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 6229–6234 (2013).

Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. Bioscience 67, 534–545 (2017).

Robinson, T. P. et al. Mapping the global distribution of livestock. PLoS ONE 9, e96084 (2014).

Gibbs, H. K., Brown, S., Niles, J. O. & Foley, J. A. Monitoring and estimating tropical forest carbon stocks: making REDD a reality. Environ. Res. Lett. 2, 045023 (2007).

Baccini, A. et al. Estimated carbon dioxide emissions from tropical deforestation improved by carbon-density maps. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 182–185 (2012).

Saatchi, S. S. et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9899–9904 (2011).

Erb, K.-H. et al. A comprehensive global 5 min resolution land-use data set for the year 2000 consistent with national census data. J. Land Use Sci. 2, 191–224 (2007).

IPCC. Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, 2006).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on earth: a new global map of terrestrial ecoregions provides an innovative tool for conserving biodiversity. Bioscience 51, 933–938 (2001).

Harrell, F. E. Jr et al. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. R package version 4.1-1. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Hmisc/Hmisc.pdf (2018).

Goldewijk, K. K., Beusen, A., Van Drecht, G. & De Vos, M. The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human-induced global land-use change over the past 12,000 years. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 20, 73–86 (2011).

Fonseca, W. et al. Carbon accumulation in the biomass and soil of different aged secondary forests in the humid tropics of Costa Rica. For. Ecol. Manage. 262, 1400–1408 (2011).

Guo, L. B. & Gifford, R. M. Soil carbon stocks and land use change: a meta analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 8, 345–360 (2002).

Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Furey, G. & Lehman, C. Soil carbon sequestration accelerated by restoration of grassland biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 10, 718 (2019).

Mitchard, E. T. et al. Uncertainty in the spatial distribution of tropical forest biomass: a comparison of pan-tropical maps. Carbon Balance Manag. 8, 10 (2013).

Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids250m: global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12, e0169748 (2017).

BirdLife International & NatureServe. Bird Species Distribution Maps of the World. Version 2018.1 http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/requestdis (BirdLife International and Handbook of the Birds of the World, 2018).

Beresford, A. et al. Poor overlap between the distribution of protected areas and globally threatened birds in Africa. Anim. Conserv. 14, 99–107 (2011).

Staude, I. R. et al. Range size predicts the risk of local extinction from habitat loss. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 16–25 (2020).

Carrasco, L. R., Webb, E. L., Symes, W. S., Koh, L. P. & Sodhi, N. S. Global economic trade-offs between wild nature and tropical agriculture. PLoS Biol. 15, e2001657 (2017).

Naidoo, R & Iwamura, T. Global-scale mapping of economic benefits from agricultural lands: implications for conservation priorities. Biol. Conserv. 140, 40–49 (2007).

Polasky, S. et al. Where to put things? Spatial land management to sustain biodiversity and economic returns. Biol. Conserv. 141, 1505–1524 (2008).

Sulser, T. B. et al. in Beyond a Middle Income Africa: Transforming African Economies for Sustained Growth with Rising Employment and Incomes (ReSAKSS Annual Trends and Outlook Report 2014 (eds. Badiane, O. et al.) Ch. 2 (International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), 2014).

Robinson, S. et al. The International Model for Policy Analysis of Agricultural Commodities and Trade (IMPACT): Model Description for Version 3 (IFPRI Discussion Paper 1483) (International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), (2015).

IIASA & FAO. Global Agro-ecological Zones (GAEZ v.3.0) (IIASA & FAO, 2012).

Hoppe, R. A. Structure and Finances of U.S. Farms: Family Farm Report (EIB-132) (US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2014).

Baležentis, T. et al. Decomposing dynamics in the farm profitability: an application of index decomposition analysis to Lithuanian FADN sample. Sustainability 11, 2861 (2019).

Statistic Canada. Table 32-10-0136-01, Farm Operating Revenues and Expenses, Annual. https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/59ca6332-391b-4fdf-bb3a-31e5e45f6bb7 (2008).

De Groot, R. S. et al. Benefits of investing in ecosystem restoration. Conserv. Biol. 27, 1286–1293 (2013).

International Labour Organization. ILOSTAT database. https://ilostat.ilo.org/data (accessed March 2020).

United Nations Statistics Division. UN Comtrade Database. https://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed March 2020).

Brancalion, P. H. S. et al. What makes ecosystem restoration expensive? A systematic cost assessment of projects in Brazil. Biol. Conserv. 240, 108274 (2019).

Mueller, N. D. et al. Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nature 490, 254–257 (2012).

Mueller, N. D. et al. Declining spatial efficiency of global cropland nitrogen allocation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 245–257 (2017).

Foley, J. A. et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 478, 337–342 (2011).

Hornik, K. et al. SYMPHONY in R, an R interface to the SYMPHONY solver for mixed-integer linear programs. http://R-Forge.R-project.org/projects/rsymphony/ (2019).

Popp, A. et al. Land-use futures in the shared socio-economic pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 331–345 (2017).

Acknowledgements

B.B.N.S. acknowledges that this work was supported by the Serrapilheira Institute (grant number Serra-1709-19329). We acknowledge inputs from the Secretariat of the Convention of Biological Diversity and experts from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. We are very grateful for the support provided by F. Gomes, J. Krieger, I. Leite, R. Capellão, G. Duarte, L. Martinez, L. Oliveira and D. Rocha in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B.N.S. conceived the study, coordinated the development of the multicriteria approach, led the analyses and wrote the first version of the paper. A.I., H.L.B. and B.B.N.S. led the multicriteria modelling. T.M.B., R.C., R.L.C. and S.H.M.B. helped with the development of the multicriteria approach. A.I., H.L.B., C.L.C., E.L., C.C.J., A.B.J., R.C., K.-H.E. and B.B.N.S. developed input datasets. S.H.M.B., G.B., P.F.D., K.-H.E. and C.P. contributed data. D.C., C.A.d.M.S. and F.R.S. helped with the interface with policy applications. B.B.N.S., A.I., H.L.B., C.L.C., R.C., C.C.J., A.B.J., E.L., A.E.L., A.B., T.M.B., S.H.M.B., R.L.C., P.B., D.C., S.D., V.K., L.M., D.L., M.O. and P.V. analysed the results. All authors provided input into subsequent versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Simon Ferrier and Robin Naidoo for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

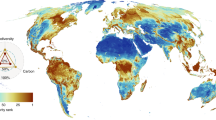

Extended Data Fig. 1 Converted lands and their estimated original ecosystem type.

a, Percentages of converted areas in each planning unit; current croplands and pasturelands are included as potentially restorable areas. b–f, Percentages of converted lands within each original ecosystem type: forests (b), natural grasslands (c), shrublands (d), wetlands (e) and arid areas (f). Areas in darker grey in b–f represent the current extent of each ecosystem type.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Benefits of ecosystem restoration for biodiversity conservation, the mitigation of climate change and associated costs.

a, Benefits for biodiversity were calculated as the number of avoided extinctions per hectare for all species combined. The map represents the starting situation with current vegetation cover before any restoration takes place. b, Benefits for climate change are calculated as the difference between the potential carbon stored after ecosystem restoration and the carbon currently stored in the agricultural lands. ‘Stock’ refers to carbon in the above- and belowground biomass and down to 30 cm in the soil, include above and belowground biomass and soil carbon sequestration. c, Costs consist of opportunity costs, based on the foregone agricultural benefits of areas allocated for restoration, and restoration implementation costs.

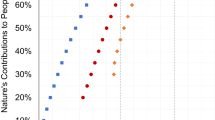

Extended Data Fig. 3 Areas potentially available for restoration and their relative priority across subregions.

a–f, For each of the 17 subregions of IPBES, the horizontal bars show their relative priority percentile for the main scenarios focused on biodiversity (a), climate change mitigation (b), minimizing costs (c), biodiversity and climate change mitigation (d) and all three criteria (e); the last panel (f) shows absolute areas. South America has the greatest extent of converted lands that are relatively evenly distributed in the top 50% of global priorities, whereas the Caribbean has the smallest extent of areas potentially available for restoration—but almost all of them are in the top 10% of global priorities. The patterns in relative priority for restoration for each subregion change substantially across the different restoration scenarios, which further highlights the importance of using multicriteria optimizations that take into account several benefits of restoration simultaneously.

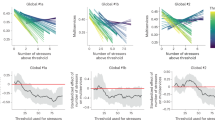

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cost-efficiency of climate change mitigation for main scenarios.

The curves show, for the 5 main scenarios and across 20 targets ranging from 5% to 100%, the carbon value required to cover both opportunity and restoration costs. These results underscore the cost effectiveness of restoration as a climate mitigation option, as carbon values are in the lower range of low and medium mitigation costs according to the IPCC1.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Distribution of major ecosystem types that could be restored.

Dominant estimated predisturbance ecosystem type in each cell; for the fraction of each ecosystem type per cell, see Extended Data Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Accuracy of original ecosystem-cover predictions.

a–f, The accuracy of the predictions of the original proportion of each ecosystem type in each planning unit was quantified using the root mean square error (r.m.s.e.). To better understand any heterogeneity in prediction accuracy, we calculated the r.m.s.e. separately for each of the five land-cover classes (forest, grassland, shrubland, wetland and desert) in addition to the overall r.m.s.e. Overall, predictive accuracy was excellent (total r.m.s.e 6.73%, f) with relatively little variation among the five land-cover types: forests, 4.0% (a); grasslands, 1.7% (b); shrublands, 4.3% (c); wetlands, 1.2% (d); and arid areas, 2.6% (e).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Fraction of converted lands available for restoration after closing yield gaps.

Combining yield gaps for croplands and pasturelands, the map indicates the fraction of a planning unit that could be spared if 75% of its yield gap were to be closed.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Global and national priority areas for restoration.

For the multiple benefits scenario and 15% restoration target, areas in green are selected both in the globally unconstrained scenario and in a scenario constrained by national boundaries; areas in red are selected only in the global scenario and areas in blue are selected only in the national version of the scenario. A substantial fraction (69%) of global priority areas would not be restored using uniform national targets. As most of these areas are in lower-income countries, the results reinforce the role that international cooperation mechanisms such as REDD+ can have in achieving cost-effective global outcomes through restoration.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Sensitivity analysis with future land-use change.

a, b, In the pessimistic regional rivalries SSP3 scenario83, substantial conversion would happen until 2050 (a), and—as a consequence—some priority areas would shift towards newly converted areas of high endemic and threatened biodiversity that are also rich in carbon, in particular in Africa (b). c–f, Despite this, the restored fraction in each planning unit would be very similar to those based on 2015 land-use (c) (r.m.s.e. = 13%), and 2050 outcomes for biodiversity (d), climate (e) and costs (f) would be within the uncertainty range of 2015 estimates. Although the reduction in extinction debt would be slightly lower in 2050 (55% versus 60%), the extinction debt itself would be 25% higher (10% versus 8% in 2015), so absolute extinctions avoided would be higher.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Comparisons between potential biomass carbon stocks calculated in this study and other estimates.

Comparisons between our estimates of potential carbon stocks in biomass (above and below-ground) and estimates from ref. 24: Forest Resources Assessment (FRA)-related map (FAO) and remote-sensing based map. Box plots are based on pixel-level estimates of carbon stocks per ha in each biome, have the same sample size (pixels) across maps, and show the median (vertical lines), the interquartile range (bounding boxes) minimum and maximum values (whiskers).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Strassburg, B.B.N., Iribarrem, A., Beyer, H.L. et al. Global priority areas for ecosystem restoration. Nature 586, 724–729 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2784-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2784-9

This article is cited by

-

A new perspective for enhancing social and ecological systems coordination in ecological restoration

Ecological Processes (2025)

-

Meeting European Union biodiversity targets under future land-use demands

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025)

-

Integrating hydrological impacts for cost-effective dryland ecological restoration

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Global blind spots in soil health research overlap with environmental vulnerability hotspots

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Overlooked discrepancies in protocols undermine coastal restoration practices in China

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

Karen Holl

Numerous recent global mapping efforts [1, 2], including this paper, have attempted to prioritize where to restore ecosystems and to estimate how much carbon restoration can sequester. These efforts have forwarded general principles for restoration planning, such as the importance of considering land opportunity costs, and identified where better data are needed. But the gross assumptions inherent to these global mapping efforts carry huge risks in misprioritizing locations for restoration, with unintended consequences for both humans and ecosystems [3, 4]. Although benefits of restoration are often well-quantified, these studies do not properly account for marked variation in restoration costs, socioeconomic risks, and restoration approaches (e.g., ranging from natural regeneration to intensive vegetation planting and maintenance) across ecosystems and regions. Thus, their detailed global restoration maps suggest a misleading level of confidence.

As we embark on the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration, there is enormous pressure to determine where to get the most bang for the buck in restoring ecosystems to sequester carbon and achieve conservation and sustainable development co-benefits. Strassburg and colleagues [5] claim that one advance of their prioritization scheme is including spatial variation in restoration costs. However, they used restoration cost values from a single ecosystem, the Brazilian Atlantic forest, and extrapolated those values across the globe, adjusting only for relative differences in labor and supply costs, despite the growing number of articles showing that restoration costs can vary by orders of magnitude depending on the ecosystem and method used [6, 7]. They draw on this analysis to offer general guidance, such as that grasslands are cheaper to restore than forests. But restoring grassland ecosystems can be quite expensive, ranging from hundreds to millions of USD per hectare, depending on the establishment method and the degree of ongoing invasive plant management that is often required [8]. Hence, Strassburg and colleagues’ cost generalizations could potentially lead to misguided choices by the growing number of governments, investors, and conservation groups who are looking to most cost effectively sequester carbon and conserve biodiversity.

Strassburg and colleagues include a one-sentence caveat that their models do not include social and cultural factors. Nonetheless, we question the applicability of models that do not include social factors that have been repeatedly demonstrated to strongly affect long-term restoration success, namely land tenure and the buy-in of stakeholders at different jurisdictional levels [4, 9]. In particular, local communities are fungible in these global prioritization models. Yet, innumerable restoration projects have failed from the absence of meaningful participation of local stakeholders in the planning process and lack of consideration of their long-term need to derive benefits from the land [10].

We recognize that it is challenging to map socioeconomic variables meaningfully at the global scale, which is why we advocate focusing on setting restoration priorities at the scale of the biome or region. For example, Strassburg et al. [11] provide important insights on where to restore in the Brazilian Atlantic forest, a region in which several of the authors have extensive experience and knowledge of regional socio-political constraints that are likely to determine project success. Likewise, Cook-Patton et al. [12] draw on various spatial datasets, economics analyses, and interviews with land managers to prioritize locations to restore forest for climate mitigation in the continental United States. At smaller scales, local and regional stakeholders can provide input on the prioritization efforts to identify key social priorities and tradeoffs [13]. Regional models do not provide a simple global map that color codes where governments or investors should choose to restore, but we contend that they better predict where restoration is more likely to succeed in delivering the desired benefits, as they draw on more diverse and nuanced data and expert opinion.

Karen D. Holl (University of California, Santa Cruz), J. Leighton Reid (Virginia Tech),

Matthew E. Fagan (University of Maryland Baltimore County)

References

1.Mappin B., Chauvenet A.L.M., Adams V.M., Di Marco M., Beyer H.L., Venter O., Halpern B.S., Possingham H.P., Watson J.E.M. 2019. Restoration priorities to achieve the global protected area target. Conservation Letters 12, e12646. (doi:10.1111/conl.12646).

2.Bastin J.-F., Finegold Y., Garcia C., Mollicone D., Rezende M., Routh D., Zohner C.M., Crowther T.W. 2019. The global tree restoration potential. Science 365, 76-79. (doi:10.1126/science.aax0848).

3.Fagan M.E. 2020. A lesson unlearned? Underestimating tree cover in drylands biases global restoration maps. Global Change Biology 26, 4679-4690. (doi:10.1111/gcb.15187).

4.Brancalion P.H.S., Holl K.D. 2020. Guidance for successful tree planting initiatives. J Appl Ecol 57, 2349-2361. (doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13725).

5.Strassburg B.B.N., Iribarrem A., Beyer H.L., Cordeiro C.L., Crouzeilles R., Jakovac C.C., Braga Junqueira A., Lacerda E., Latawiec A.E., Balmford A., et al. 2020. Global priority areas for ecosystem restoration. Nature 586, 724-729. (doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2784-9).

6.Brancalion P.H.S., Meli P., Tymus J.R.C., Lenti F.E.B., M. Benini R., Silva A.P.M., Isernhagen I., Holl K.D. 2019. What makes ecosystem restoration expensive? A systematic cost assessment of projects in Brazil. Biol Conserv 240, 108274. (doi:j.biocon.2019.108274).

7.Bayraktarov E., Saunders M.I., Abdullah S., Mills M., Beher J., Possingham H.P., Mumby P.J., Lovelock C.E. 2016. The cost and feasibility of marine coastal restoration. Ecol Appl 26, 1055-1074. (doi:10.1890/15-1077).

8.Török P., Vida E., Deák B., Lengyel S., Tóthmérész B. 2011. Grassland restoration on former croplands in Europe: an assessment of applicability of techniques and costs. Biodivers Conserv 20, 2311-2332. (doi:10.1007/s10531-011-9992-4).

9.Mansourian S., Vallauri D. 2014. Restoring forest landscapes: important lessons learnt. Environ Manag 53, 241-251. (doi:10.1007/s00267-013-0213-7).

10.Reid J.L., Wilson S.J., Bloomfield G.S., Cattau M.E., Fagan M.E., Holl K.D., Zahawi R.A. 2017. How long do restored ecosystems persist? Ann Mo Bot Gard 102, 258-265. (doi:10.3417/2017002).

11.Strassburg B.B.N., Beyer H.L., Crouzeilles R., Iribarrem A., Barros F., de Siqueira M.F., Sánchez-Tapia A., Balmford A., Sansevero J.B.B., Brancalion P.H.S., et al. 2019. Strategic approaches to restoring ecosystems can triple conservation gains and halve costs. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3, 62-70. (doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0743-8).

12.Cook-Patton S.C., Gopalakrishna T., Daigneault A., Leavitt S.M., Platt J., Scull S.M., Amarjagal O., Ellis P.W., Griscom B.W., McGuire J.L., et al. 2020. Lower cost and more feasible options to restore forest cover in the contiguous United States for climate mitigation. One Earth 3. (doi:doi.org/10.1016/j.oneea....

13.Guerrero A.M., Shoo L., Iacona G., Standish R.J., Catterall C.P., Rumpff L., de Bie K., White Z., Matzek V., Wilson K.A. 2017. Using structured decision-making to set restoration objectives when multiple values and preferences exist. Restor Ecol 25, 858-865. (doi:10.1111/rec.12591).

J. Leighton Reid

Southeastern US Grasslands are a globally-relevant restoration priority

We commend Strassburg et al. (see Nature 586, 724: 2020) for a first attempt at a multi-biome prioritization for terrestrial ecological restoration. However, we disagree with their assertion that agricultural lands in the US Southeast should be restored to forest (their Extended Data Fig. 5), and that restoration in this region is not a global priority. By failing to recognize the restoration potential of Southeastern grasslands, savannas, and open woodlands, this paper sends an inaccurate message to restoration funders at the start of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Longleaf pine savanna and other native grasslands in the Southeastern mountains, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain once covered more than 36 million hectares from Virginia to Texas. Afforestation – including misguided restoration – is a primary threat to grasslands throughout the world, including the US Southeast (J. W. Veldman et al. Science 347, 484; 2015). For example, the Coastal Plain alone contains >1800 endemic plant species and has lost >85% of its original habitat, much of that to short-rotation timber plantations and suppression of fire. This level of biodiversity and threat places the North American Coastal Plain among the world’s biodiversity hotspots (R. F. Noss, et al. Div. & Dist. 21, 236; 2015).

The misrepresentation of native grasslands, savannas, and open woodlands as forests highlights that these communities still face an uphill battle for recognition, appreciation, and funding. To fail to restore grass-dominated ecosystems is to miss a key opportunity to conserve endemic species, improve groundwater recharge, and sequester carbon in ecosystems that are more resilient than forests to increasingly common fires, droughts, and heatwaves. Restoring these native communities is a global priority.

J. Leighton Reid, School of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Virginia Tech

Dwayne Estes, Southeastern Grasslands Initiative, Center for Field Biology, Austin Peay State University

Reed F. Noss, Southeastern Grasslands Initiative

Frank Holzman

Restoring habitats and creating balanced ecosystems as a way to grow food is an important part of becoming good stewards of the planet. A Radiant Earth, offers ideas on using agroecology, agroforestry, remediation, reforestation, mycology and much more, not only to develop balanced ecosystems but also to develop good stewards of the land.