Abstract

Here we report on the nearly complete and uncrushed 14th specimen of Archaeopteryx. Exceptional preservation and preparation guided by micro-computed tomographic data make this one of the best exemplars of this iconic taxon, preserving important data regarding skeletal transformation and plumage evolution in relation to the acquisition of flight during early avian evolution. The ventrolaterally exposed skull reveals a palatal morphology intermediate between troodontids1 and crownward Cretaceous birds2,3. Modifications of the skull reflect the shift towards a less rigid cranial architecture in archaeopterygids from non-avian theropods. The complete vertebral column reveals paired proatlases and a tail longer than previously recognized. Skin traces on the right major digit of the hand suggest that the minor digit was free and mobile distally, contrary to previous interpretations4. The morphology of the foot pads indicates that they were adapted for non-raptorial terrestrial locomotion. Specialized inner secondary feathers called tertials5,6 are observed on both wings. Humeral tertials are absent in non-avian dinosaurs closely related to birds, suggesting that these feathers evolved for flight, creating a continuous aerodynamic surface. These new findings clarify the mosaic of traits present in Archaeopteryx, refine ecological predictions and elucidate the unique evolutionary history of the Archaeopterygidae, providing clues regarding the ancestral avian condition.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tsuihiji, T. et al. An exquisitely preserved troodontid theropod with new information on the palatal structure from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Naturwissenschaften 101, 131–142 (2014).

Wang, M., Stidham, T. A., Li, Z.-H., Xu, X. & Zhou, Z.-H. Cretaceous bird with dinosaur skull sheds light on avian cranial evolution. Nat. Commun. 12, 3890 (2021).

Hu, H. et al. Earliest evidence for fruit consumption and potential seed dispersal by birds. eLife 11, e74751 (2022).

Elzanowski, A. in Mesozoic Birds: above the Heads of Dinosaurs (eds Chiappe, L. M. & Witmer, L. M.) 129–159 (Univ. California Press, 2002).

Terrill, R. S. & Shultz, A. J. Feather function and the evolution of birds. Biol. Rev. 98, 540–566 (2023).

Hickman, S. The trouble with tertials. Auk 152, 493 (2008).

Sereno, P. C. The evolution of dinosaurs. Science 284, 2137–2147 (1999).

Foth, C., Tischlinger, H. & Rauhut, O. W. M. New specimen of Archaeopteryx provides insights into the evolution of pennaceous feathers. Nature 511, 79–82 (2014).

Voeten, D. F. A. E. et al. Wing bone geometry reveals active flight in Archaeopteryx. Nat. Commun. 9, 923 (2018).

Wellnhofer, P. Archaeopteryx, English Edition: The Icon Of Evolution (Pfeil, 2009).

Rauhut, O. W. M., Foth, C. & Tischlinger, H. The oldest Archaeopteryx (Theropoda: Avialiae): a new specimen from the Kimmeridgian/Tithonian boundary of Schamhaupten, Bavaria. PeerJ 6, e4191 (2018).

Elzanowski, A. A novel reconstruction of the skull of Archaeopteryx. Neth. J. Zool. 51, 207–215 (2001).

Mayr, G., Pohl, B., Hartman, S. & Peters, D. S. The tenth skeletal specimen of Archaeopteryx. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 149, 97–116 (2007).

Yin, Y.-L., Pei, R. & Zhou, C.-F. Cranial morphology of Sinovenator changii (Theropoda: Troodontidae) on the new material from the Yixian Formation of western Liaoning, China. PeerJ 6, e4977 (2018).

Currie, P. J. New information on the anatomy and relationships of Dromaeosaurus albertensis (Dinosaura: Theropoda). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 15, 576–591 (1995).

Hu, H. et al. Evolution of the vomer and its implications for cranial kinesis in Paraves. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19571–19578 (2019).

Wang, M., Stidham, T. A., O’Connor, J. K. & Zhou, Z.-H. Insight into the evolutionary assemblage of cranial kinesis from a Cretaceous bird. eLife 11, e81337 (2022).

Elzanowski, A. & Wellnhofer, P. Cranial morphology of Archaeopteryx: evidence from the seventh skeleton. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 16, 81–94 (1996).

Mayr, G., Pohl, B. & Peters, D. S. A well-preserved Archaeopteryx specimen with theropod features. Science 310, 1483–1486 (2005).

Wang, M., Wang, X.-L., Zheng, X.-T. & Zhou, Z.-H. Cranial anatomy of Anchiornis huxleyi (Theropoda: Paraves) sheds new light on bird skull evolution. Vertebr. Palasiat. 63, 20–42 (2025).

Wu, Y.-H., Chiappe, L. M., Bottjer, D. J., Nava, W. & Martinelli, A. G. Dental replacement in Mesozoic birds: evidence from newly discovered Brazilian enantiornithines. Sci. Rep. 11, 19349 (2021).

Zhou, Z. & Zhang, F. Two new ornithurine birds from the Early Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 46, 1258–1264 (2001).

Kundrát, M., Nudds, J., Kear, B. P., Lü, J.-C. & Ahlberg, P. E. The first specimen of Archaeopteryx from the Upper Jurassic Mörnsheim Formation of Germany. Hist. Biol. 31, 3–63 (2019).

Makovicky, P. J., Norell, M. A., Clark, J. M. & Rowe, T. Osteology and relationships of Byronosaurus jaffei (Theropoda: Troodontidae). Am. Mus. Novit. 3402, 1–32 (2003).

Pei, R. et al. Osteology of a new Late Cretaceous troodontid specimen from Ukaa Tolgod, Ömnögovi Aimag, Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit. 3889, 1–47 (2017).

Pei, R. et al. Potential for powered flight neared by most close avialan relatives, but few crossed its thresholds. Curr. Biol. 30, 4033–4046 (2020).

Godefroit, P. et al. A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds. Nature 498, 359–362 (2013).

O’Connor, J. & Chiappe, L. M. A revision of enantiornithine (Aves: Ornithothoraces) skull morphology. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 9, 135–157 (2011).

Clarke, J. A. Morphology, phylogenetic taxonomy, and systematics of Ichthyornis and Apatornis (Avialae: Ornithurae). Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 286, 1–179 (2004).

Sumida, S. S., Lombard, R. E. & Berman, D. S. The atlas-axis complex of the Late Paleozoic Diadectomorpha and basal amniotes: defining the primitive condition of the atlas-axis complex of amniotes. Paleontol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 6, 283 (2017).

Norell, M. A. et al. A new dromaeosaurid theropod from Ukhaa Tolgod (Ömnögov, Mongolia). Am. Mus. Novit. 3545, 1–51 (2006).

Chiappe, L. M., Ji, S., Ji, Q. & Norell, M. A. Anatomy and systematics of the Confuciusornithidae (Theropoda: Aves) from the Late Mesozoic of northeastern China. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 242, 1–89 (1999).

Liu, D. et al. Cranial and dental morphology in a bohaiornithid enantiornithine with information on its tooth replacement pattern. Cretaceous Res. 129, 105021 (2022).

Ostrom, J. H. Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an unusual theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana. Bull. Peabody Mus. Nat. Hist. 30, 1–165 (1969).

Wollin, D. G. The os odontoideum. Separate odontoid process. J. Bone Joint Surg. 45A, 1459–1471 (1963).

Baumel, J. J., King, A. S., Breazile, J. E., Evans, H. E. & Vanden Berge, J. C. in Publ. Nuttall Ornithol. Club Vol. 23 (ed. Baumel, J. J.) 779 (Nuttall Ornithological Club, 1993).

Turner, A. H., Pol, D. & Norell, M. A. Anatomy of Mahakala omnogovae (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae), Tögrögiin Shiree, Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit. 3722, 1–66 (2011).

Botelho, J. F. et al. New developmental evidence clarifies the evolution of wrist bones in the dinosaur–bird transition. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001957 (2014).

Hopson, J. A. in New Perspectives on the Origin and Early Evolution of Birds (eds Gauthier, J. & Gall, L. F.) 211–235 (Peabody Museum of Natural History, 2001).

Pittman, M. et al. Exceptional preservation and foot structure reveal ecological transitions and lifestyles of early theropod flyers. Nat. Commun. 13, 7684 (2022).

Lennerstedt, I. Pattern of pads and folds in the foot of European Oscines (Aves, Passeriformes). Zool. Scr. 4, 101–109 (1975).

Elzanowski, A. The life style of Archaeopteryx (Aves). In Proc. VII International Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems Vol. 7 Asociación Paleontológica Argentina Publicación Especial (ed. Leanza, H.A.) 91–99 (Asociación Paleontológica Argentina, 2001).

Yalden, D. W. What size was Archaeopteryx? Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 82, 177–188 (1984).

Wang, M., O’Connor, J., Xu, X. & Zhou, Z.-H. A new Jurassic scansoriopterygid and the loss of membranous wings in theropod dinosaurs. Nature 569, 256–259 (2019).

Hedenström, A. Effects of wing damage and moult gaps on vertebrate flight performance. J. Exp. Biol. 226, jeb227355 (2023).

Jenni, L. & Winkler, R. The Biology of Moult in Birds (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Ellis, D. H., Swengel, S. R., Archibald, G. W. & Kepler, C. B. A sociogram for the cranes of the world. Behav. Process. 43, 125–151 (1998).

Zheng, X.-T. et al. Hind wings in basal birds and the evolution of leg feathers. Science 339, 1309–1312 (2013).

Zhang, F. & Zhou, Z. Leg feathers in an Early Cretaceous bird. Nature 431, 925 (2004).

O’Connor, J. in The Evolution of Feathers (eds Foth, C. & Rauhut, O. W. M.) 147–172 (Springer, 2020).

Wang, X.-L. et al. Archaeorhynchus preserving significant soft tissue including probable fossilized lungs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 11555–11560 (2018).

Field, D. J. et al. Complete Ichthyornis skull illuminates mosaic assembly of the avian head. Nature 557, 96–100 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Lumbsch, B. Lauer and R. Lauer for facilitating the specimen acquisition; A. Stroup for assisting with figures; M. Colbert, J. Maisano and D. Edey for scanning the main slab; C. Wang and X. Zhang for segmentation assistance; S. Selzer for aiding preparation; D. Drummond and J. Stierberger for photographing the specimen; and B. Marks for access to extant bird specimens. M.W. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42225201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.O’C. led the research and wrote the manuscript; H.H. led the segmentation; M.F., P.-C.K. and J.L. assisted with segmentation; A.C., P.-C.K., M.F., H.H., Y.K. and M.W. assisted with research and manuscript preparation; A.S. and C.V.B. prepared the specimen.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Jessie Atterholt, Daniel Field, Johan Lindgren, Patrick O'Connor and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

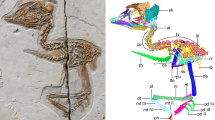

Extended Data Fig. 1 3D reconstructed models of cranial elements based on CT data of Archaeopteryx FMNH PA 830.

a-c, premaxillae in right lateral, ventral, and caudal view; d-f, vomer in dorsal, left lateral, and ventral view; g-i, right maxilla in lateral, medial and ventromedial view; j-l, right postorbital in medial, rostral, and medial view; m-p, left ectopterygoid in ventral, dorsal, lateral, and medial view; q-v, left pterygoid in ventral, dorsal, cranial, caudal, lateral, and medial view; w-aa, left palatine in rostral, dorsal, ventral, lateral, and medial view. Scale bar equals five millimeters. cf, caudal fork; cp, choanal process; fp, frontal process; jp, jugal process; lp, lateral process; mf, maxillary fenestra; mp, maxillary process; np, nasal process; pf, pterygoid flange; pr, promaxillary fenestra; pp, premaxillary process; pt, pterygoid process; qw, quadrate wing; rp, rostral process; sp, squamosal process.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Reconstructions of the palate.

a, modified from Elzanowski (2001); b, modified from Mayr et al.13; c, current reconstruction based on new data from the Chicago Archaeopteryx (FMNH PA 830). The palatal elements are color coded: orange, vomer; green, palatine; dark orange, ectopterygoid; pink, jugal; light blue, pterygoid; dark blue, quadrate; yellow, basicranium.

Extended Data Fig. 3 CT data of the proatlas and atlas in the Chicago Archaeopteryx and the comparative anatomy of the proatlas and atlas (atlas intercentrum and neurapophyses) in paravians.

Elements, all figured in right lateral view, are to scale relative to each other but not between taxa. The proatlas is colored olive green; the atlas neurapophysis is pink; the atlas intercentrum is light green. Sinovenator is based on PMOL (Paleontology Museum of Liaoning) -AD00102; Tsaagan is based on IGM, Institute of Geology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, 100/105; and Deinonychus is based on YPM, Yale Peabody Museum, 5210. Dashed lines indicate poor preservation. Fused atlas (only right neurapophysis could be reconstructed) in Archaeopteryx FMNH PA 830 in caudal (a) and cranial (b) view; right proatlas in lateral (c), medial (d), caudal (e), and cranial (f) view.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Close up photograph (a) and interpretative line drawing (b) of the left wrist in Archaeopteryx FMNH PA 830.

Scale bar equals 2 mm. Anatomical abbreviations not listed in Fig. 1 caption: sl, semilunate carpal. Grey indicates damaged bone. The carpals were identified based on 2D observations; the smallest carpals (scapholunare and distal carpal 3) could not be reconstructed from the CT data.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The plantar foot pads of terrestrial, arboreal, and raptorial birds in right lateral and plantar aspects.

Extant arboreal taxa Hylocichla mustelina (a) and Cyanocitta cristata (b); terrestrial taxon Coturnix coturnix (c-d); raptorial taxon Buteo jamaicensis (e-f). Fossil taxa represented by (g-h) enantiornithine indet. HPG-15-1 (Xing et al., 2017); (i-j) Archaeopteryx FMNH PA 830; and (k) Microraptor STM5-109 (Pittman et al. 40). All extant specimens represent recently deceased individuals being prepared for the skeletonization at the Field Museum and thus lack catalog numbers. All extant bird photos by A. D. Clark.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Preserved feather tracts in the Chicago Archaeopteryx FMNH PA 830.

Scale bar equals five centimeters.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Plumage details in Archaeopteryx FMNH PA 830.

a, scapulars and left humeral and ulnar tertials under UVABC; b, c, close up of the left tertials showing the preservation of barbs, rachises, and vane symmetry; d, open pennaceous body feathers preserved dorsal to the proximal caudal vertebrae and projecting off the left femur; e, close up of the open pennaceous feathers preserved in (d). Scale bar in (a) equals 2 cm, 5 mm in (b-c, e), and 1 cm in (d). Anatomical abbreviations not listed in Fig. 1 caption: ba, barbs; cv, wing coverts; op, open pennaceous body feathers; rh, rachis.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The function of tertial feathers.

In many modern birds, the tertial feathers (black arrows; red feathers, inset) are morphologically distinct. These feathers function as protection for the remiges from abrasion when the bird is not flying and are particularly developed in species that feed on the ground, such as (a) wagtails (Motacillidae; pictured, Eastern Yellow Wagtail Motacilla tschutschensis; photo by Y. Kiat), and (b) many shorebirds (Charadriiformes; pictured, Buff-breasted Sandpiper Calidris subruficollis; photo by I. Davies, ML110171881, adapted with permission from Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library). These feathers may also help close the gap between the secondary feathers and the bird’s body, thereby improving aerodynamic performance. Additionally, the tertials may be used for display and visual communication, as observed among some cranes (Gruiformes), such as the elongated tertials in the (c) Blue Crane (Anthropoides paradiseus; photo by M. McCloy, ML136331631, adapted with permission from Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library), or the prominent white tertials contrasting with the dark wing and body plumage in the (d) Pale-winged Trumpeter (Psophia leucoptera; photo by T. Palliser, ML62921801, adapted with permission from Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Reconstruction of the plumage of Archaeopteryx by Michael Rothman.

The black and white pattern of the feathers is based on previous research that indicates the isolated wing covert was black and white (Carney et al., 2012). This Chicago specimen reveals the presence of the enlarged tertial tract.

Supplementary information

Supplemental Information

Supplementary Methods, Discussion, Fig. 1, Tables 1–3 and References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Connor, J., Clark, A., Kuo, PC. et al. Chicago Archaeopteryx informs on the early evolution of the avian bauplan. Nature 641, 1201–1207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08912-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08912-4

This article is cited by

-

How did birds evolve? The answer is wilder than anyone thought

Nature (2026)

-

Wing morphology of Anchiornis huxleyi and the evolution of molt strategies in paravian dinosaurs

Communications Biology (2025)