Abstract

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), one of the world’s most valuable vegetable crops, has suffered from diminished genetic diversity and stress resistance. Wild tomatoes serve as an invaluable genetic reservoir, yet their potential for stress resilience remains largely unexploited in tomato breeding. Here we report a genus-wide super-pangenome across 16 tomato species by integrating 20 telomere-to-telomere genomes and 27 published chromosome-scale genomes. Genus-wide population analysis demonstrates broad genetic diversity with limited gene flows among principal clades. Pan-centromere analysis reveals a diverse landscape and dynamic evolution of the mysterious tomato centromeres involving rapid diversification, satellite emergence and repositioning. A comprehensive catalog of structural variants uncovers extensive rearrangements, especially from wild tomatoes, and discovers key molecular markers associated with salinity resistance. Structural-variant-based genome-wide association studies identified a leucine-rich repeat receptor gene SlGMAK conferring gray mold resistance. Our telomere-to-telomere super-pangenome will accelerate exploiting the untapped potential of wild relatives to improve modern tomatoes for stress resilience.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All raw sequencing data and genome assemblies generated in this study have been deposited in the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/, BioProject accession PRJCA030093). Whole-genome resequencing, CENH3 ChIP–seq, ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data have also been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, BioProject accession PRJNA1201608). The genome assemblies and annotations are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17878268 (ref. 101). Tomato whole-genome resequencing data used in this study were downloaded from NCBI under BioProject PRJEB5235. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The scripts used in this study are available via GitHub at https://github.com/ChunmeiShi02/TomatoT2Tsuperpangenome and via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17935735 (ref. 102).

References

Lin, T. et al. Genomic analyses provide insights into the history of tomato breeding. Nat. Genet. 46, 1220–1226 (2014).

Knapp, S. & Peralta, I. E. in The Tomato Genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes (eds Causse, M. et al.) 7–21 (Springer, 2016).

Ercolano, M. R., Di Matteo, A., Andolfo, G. & Frusciante, L. in The Wild Solanums Genomes (eds Carputo, D. et al.) 35–49 (Springer, 2021).

Martin, G. B. et al. Map-based cloning of a protein kinase gene conferring disease resistance in tomato. Science 262, 1432–1436 (1993).

Yang, H. et al. The Sm gene conferring resistance to gray leaf spot disease encodes an NBS-LRR (nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat) plant resistance protein in tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 135, 1467–1476 (2022).

Powell, A. F. et al. A Solanum lycopersicoides reference genome facilitates insights into tomato specialized metabolism and immunity. Plant J. 110, 1791–1810 (2022).

van Rengs, W. M. J. et al. A chromosome scale tomato genome built from complementary PacBio and Nanopore sequences alone reveals extensive linkage drag during breeding. Plant J. 110, 572–588 (2022).

Yu, X. et al. Chromosome-scale genome assemblies of wild tomato relatives Solanum habrochaites and Solanum galapagense reveal structural variants associated with stress tolerance and terpene biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac139 (2022).

The Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485, 635–641 (2012).

Zhou, Y. et al. Graph pangenome captures missing heritability and empowers tomato breeding. Nature 606, 527–534 (2022).

Chen, Y., Tian, J., Zhao, Y., Zhang, J. & Liang, C. A telomere-to-telomere reference genome assembly of tomato cultivar ‘Heinz 1706’. Plant Commun. 6, 101618 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Telomere-to-telomere Citrullus super-pangenome provides direction for watermelon breeding. Nat. Genet. 56, 1750–1761 (2024).

Shang, L. et al. A super pan-genomic landscape of rice. Cell Res. 32, 878–896 (2022).

Jayakodi, M. et al. Structural variation in the pangenome of wild and domesticated barley. Nature 636, 654–662 (2024).

Tong, X. et al. High-resolution silkworm pan-genome provides genetic insights into artificial selection and ecological adaptation. Nat. Commun. 13, 5619 (2022).

Gao, L. et al. The tomato pan-genome uncovers new genes and a rare allele regulating fruit flavor. Nat. Genet. 51, 1044–1051 (2019).

Alonge, M. et al. Major impacts of widespread structural variation on gene expression and crop improvement in tomato. Cell 182, 145–161.e23 (2020).

Li, N. et al. Super-pangenome analyses highlight genomic diversity and structural variation across wild and cultivated tomato species. Nat. Genet. 55, 852–860 (2023).

Aflitos, S. et al. Exploring genetic variation in the tomato (Solanum section Lycopersicon) clade by whole-genome sequencing. Plant J. 80, 136–148 (2014).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. J. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Benoit, M. et al. Solanum pan-genetics reveals paralogues as contingencies in crop engineering. Nature 640, 135–145 (2025).

Henikoff, S., Ahmad, K. & Malik, H. S. The centromere paradox: stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science 293, 1098–1102 (2001).

Chen, W. et al. Two telomere-to-telomere gapless genomes reveal insights into Capsicum evolution and capsaicinoid biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 15, 4295 (2024).

Chen, W. et al. The complete genome assembly of Nicotiana benthamiana reveals the genetic and epigenetic landscape of centromeres. Nat. Plants 10, 1928–1943 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Boom-bust turnovers of megabase-sized centromeric DNA in Solanum species: rapid evolution of DNA sequences associated with centromeres. Plant Cell 26, 1436–1447 (2014).

Chang, S. B. et al. FISH mapping and molecular organization of the major repetitive sequences of tomato. Chromosome Res. 16, 919–933 (2008).

Kasinathan, S. & Henikoff, S. Non-B-form DNA is enriched at centromeres. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 949–962 (2018).

Mandáková, T., Hloušková, P., Koch, M. A. & Lysak, M. A. Genome evolution in Arabideae was marked by frequent centromere repositioning. Plant Cell 32, 650–665 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Pan-centromere reveals widespread centromere repositioning of soybean genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2310177120 (2023).

Pedley, K. F. & Martin, G. B. Molecular basis of Pto-mediated resistance to bacterial speck disease in tomato. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41, 215–243 (2003).

Goel, M., Sun, H., Jiao, W. B. & Schneeberger, K. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 20, 277 (2019).

Hickey, G. et al. Genotyping structural variants in pangenome graphs using the vg toolkit. Genome Biol. 21, 35 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Loss of salt tolerance during tomato domestication conferred by variation in a Na+/K+ transporter. EMBO J. 39, e103256 (2020).

Guo, M. et al. Loss of cold tolerance is conferred by absence of the WRKY34 promoter fragment during tomato evolution. Nat. Commun. 15, 6667 (2024).

Mu, Q. et al. Fruit weight is controlled by cell size regulator encoding a novel protein that is expressed in maturing tomato fruits. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006930 (2017).

Williamson, B. et al. Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 561–580 (2007).

Khan, A. W. et al. Super-pangenome by integrating the wild side of a species for accelerated crop improvement. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 148–158 (2020).

Davis, J. et al. Mapping of loci from Solanum lycopersicoides conferring resistance or susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea in tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119, 305–314 (2009).

Finkers, R. et al. Three QTLs for Botrytis cinerea resistance in tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 585–593 (2007).

Finkers, R. et al. Quantitative resistance to Botrytis cinerea from Solanum neorickii. Euphytica 159, 83–92 (2008).

Strickler, S. R. et al. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic discordance of cultivated tomato and close wild relatives. PeerJ 3, e793 (2015).

Darwin, S. C., Knapp, S. & Peralta, I. E. J. Taxonomy of tomatoes in the Galápagos Islands: native and introduced species of Solanum section Lycopersicon (Solanaceae). Syst. Biodivers. 1, 29–53 (2003).

Lim, K. B. et al. Characterization of rDNAs and tandem repeats in the heterochromatin of Brassica rapa. Mol. Cells 19, 436–444 (2005).

Hu, J. et al. NextDenovo: an efficient error correction and accurate assembly tool for noisy long reads. Genome Biol. 25, 107 (2024).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Alonge, M. et al. Automated assembly scaffolding using RagTag elevates a new tomato system for high-throughput genome editing. Genome Biol. 23, 258 (2022).

Xu, M. et al. TGS-GapCloser: a fast and accurate gap closer for large genomes with low coverage of error-prone long reads. GigaScience 9, giaa094 (2020).

Jain, C., Rhie, A., Hansen, N. F., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Long-read mapping to repetitive reference sequences using Winnowmap2. Nat. Methods 19, 705–710 (2022).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Huang, N. & Li, H. Compleasm: a faster and more accurate reimplementation of BUSCO. Bioinformatics 39, btad595 (2023).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. J. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob. DNA 6, 11 (2015).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 25, 4.10.1–4.10.14 (2009).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 18, 188–196 (2008).

Slater, G. S. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 31 (2005).

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 59 (2004).

Hoff, K. J., Lomsadze, A., Borodovsky, M. & Stanke, M. Whole-genome annotation with BRAKER. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962, 65–95 (2019).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Nevers, Y. et al. Quality assessment of gene repertoire annotations with OMArk. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 124–133 (2025).

Wlodzimierz, P. et al. Cycles of satellite and transposon evolution in Arabidopsis centromeres. Nature 618, 557–565 (2023).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Ramírez, F., Dündar, F., Diehl, S., Grüning, B. A. & Manke, T. DeepTools: a flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W187–W191 (2014).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18 (2008).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Vollger, M. R., Kerpedjiev, P., Phillippy, A. M. & Eichler, E. E. StainedGlass: interactive visualization of massive tandem repeat structures with identity heatmaps. Bioinformatics 38, 2049–2051 (2022).

Tarasov, A., Vilella, A. J., Cuppen, E., Nijman, I. J. & Prins, P. Sambamba: fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics 31, 2032–2034 (2015).

Yu, H., Shi, C., He, W., Li, F. & Ouyang, B. PanDepth, an ultrafast and efficient genomic tool for coverage calculation. Brief Bioinform. 25, bbae197 (2024).

Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 43, 11.10.1–11.10.33 (2013).

Li, H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27, 2987–2993 (2011).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80–92 (2012).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Kozlov, A. M., Darriba, D., Flouri, T., Morel, B. & Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 35, 4453–4455 (2019).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Särkinen, T., Bohs, L., Olmstead, R. G. & Knapp, S. A phylogenetic framework for evolutionary study of the nightshades (Solanaceae): a dated 1000-tip tree. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 214 (2013).

Chen, H. & Zwaenepoel, A. Inference of ancient polyploidy from genomic data. Methods Mol. Biol. 2545, 3–18 (2023).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Steuernagel, B. et al. The NLR-annotator tool enables annotation of the intracellular immune receptor repertoire. Plant Physiol. 183, 468–482 (2020).

Smith, M., Jones, J. T. & Hein, I. Resistify: a novel NLR classifier that reveals Helitron-associated NLR expansion in Solanaceae. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 19, 11779322241308944 (2025).

Ngou, B. P. M., Heal, R., Wyler, M., Schmid, M. W. & Jones, J. D. G. Concerted expansion and contraction of immune receptor gene repertoires in plant genomes. Nat. Plants 8, 1146–1152 (2022).

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195 (2011).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Jeffares, D. C. et al. Transient structural variations have strong effects on quantitative traits and reproductive isolation in fission yeast. Nat. Commun. 8, 14061 (2017).

Kang, H. M. et al. Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 42, 348–354 (2010).

Li, M. X., Yeung, J. M., Cherny, S. S. & Sham, P. C. Evaluating the effective numbers of independent tests and significant p-value thresholds in commercial genotyping arrays and public imputation reference datasets. Hum. Genet. 131, 747–756 (2012).

Fu, J. et al. Resistance to RNA interference by plant-derived double-stranded RNAs but not plant-derived short interfering RNAs in Helicoverpa armigera. Plant Cell Environ. 45, 1930–1941 (2022).

Shi, C., Chen, S. & Wang, J. Tomato telomere-to-telomere super pangenome empowers stress resilience breeding. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17878268 (2025).

Shi, C., Chen, S. & Wang, J. Codes for a tomato telomere-to-telomere super pangenome. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17935735 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Huang for constructive suggestions on the paper, and the Tomato Genetics Resource Center at the University of California, Davis, for providing seeds for wild tomato accessions. We thank the Bioinformatics Platform at Peking University Institute of Advanced Agricultural Sciences for providing the high-performance computing resources. This work was supported by the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (project 2025CXPT174 and 2025CXPT160 to C.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32500545 to W.C.), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (project SYS202206), the Yuandu Scholars Program, and the Taishan Scholars Program and Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (ZR2023JQ010 to L.G.) of Shandong Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y. and L.G. conceived and supervised the project. Q.G. collected material phenotypes. D.M. and X.S. prepared the biological materials for sequencing. C. Shi, S.C., J.W. and W.C. performed bioinformatic analyses and prepared tables and figures. C. Sun conducted gene functional analysis. S.L., H.W., Y.M., X.S., J.Z. and L.D. carried out molecular experiments. C. Shi, L.G., C.Y. and W.C. wrote and revised the paper. L.Z. and S.H. participated in discussion and result interpretation. All authors read and approve the final paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Genetics thanks Michael Bevan and Xingtan Zhang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

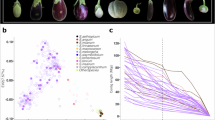

Extended Data Fig. 1 An overview of the tomato graph super-pangenome in this study.

a, The SL6.0 T2T genome enables comprehensive population analysis across 294 wild and cultivated tomato accessions. b, Construction of the super-pangenome and investigation of pan-centromere evolution. c, A graph-based super-pangenome facilitates discovering genetic variations associated with salt tolerance and grey mold resistance. d, Editing and establishing new editing systems in wild species or cultivated varieties for de novo crop domestication.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Genome assembly and annotation of S. lycopersicum T2T gap-free genome.

a, Whole-genome coverage of HiFi reads across the SL6.0 assembly. Regions with read depth below 100 or above 250 were marked by black shades. The GC content was shown as a blue curve. 5S rDNA was marked by blue boxes. Satellites were marked by red boxes. b, Examples of gap-closures on Chr04 and Chr05 for SL6.0 genome assembly. c. Comparison of the annotated proteomes from SL6.0 and SL5.0 genome.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Genome statistics and correlation with transposons in 20 wild and cultivated tomato genomes.

a, Genome size and N50 length statistics for the genomes analyzed in the study. b, Correlation between the size genomes and the length of TE across the 20 newly assembled genomes. c-f, Correlation between genome size and the length of different TE types, including Gypsy (c), DNA (d), LINE (e), and Copia (f) elements. Pearson correlation coeficients, the 95% confdence interval are shown for each comparison.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Evolution of centromeres in wild and cultivated tomatoes.

a-b, Distribution of Gypsy and specific satellites as well as CENH3 enrichment on chromosomes Chr02 (a) and Chr03 (b). Six species from five clades are taken as representatives. The Clade5 includes a closely related wild species and a widely-used domesticated tomato. The centromeres are marked with grey background boxes.

Extended Data Fig. 5 A proposed evolutionary model of satellite-based centromeres in tomatoes.

a, Evolution of specific satellites in wild and cultivated tomatoes. The boxes represent the type of specific 24-bp (Sat24) or 53-bp (Sat53) repeats. The circles showing presence of specific satellite for each chromosome (column) and accession (row). b, Comparison of two 45S rDNA monomers from S. lycopersicum and N. benthamiana illustrating the origin of specific Sat53 and centromere-specific CEN33/43 satellites, respectively. c, A proposed evolutionary pathway for formation of satellite-type centromeres in cultivated tomatoes. The centromere of Solanum ancestor was probably dominated by Gypsy retrotransposons; then Sat24 emerged in ancient wild tomatoes (for example JUG) and acted as centromeres. After that, the Sat24 degenerated while the Sat53 emerged in LYC, probably originated from the subrepeat of 45S rDNA; then Sat53 expanded approaching to original centromeres, which then employed CENH3 protein in wild tomatoes (for example PER). After that, the satellite-type centromeres (most exclusively dominated by Sat53) formed and matured in cultivated tomatoes, although there were only one or two.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Pan-NLRome analysis of 20 wild and cultivated tomatoes.

a, Statistics of pan- and core-NLR size across 20 tomato genomes, classified using OrthoFinder. The x-axis indicates the number of tomato accessions, while the y-axis indicates the number of gene families. The central line denotes the median, and the edges of the box define the first and third quartiles. The whiskers extend to the range of datapoints within 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) (the same for all subsequent boxplots) b, Core, softcore, dispensable and private NLR genes from 20 tomato genomes. Core NLR genes (present in 20 accessions), soft core NLR genes (present in 18-19 accessions), Dispensable NLR genes (present in 2-17 accessions) and private NLR genes (present in only one accession). c, Presence and absence information of NLR genes in 20 tomato genomes. d, Pan-NLRome landscape of tomato species from different clades. e, The microsyntenic relationships of one NLR gene clusters on Chr05 in three tomato accessions. SLL A, M82; SLL B, Heinz 1706; SLL C, TS-60; SLL D, AC.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Structural variation landscape and Pan-SV analysis of wild and cultivated tomatoes.

a, SV size distribution. TRA: translocation. INV: inversion. DEL: deletion. INS: insertion. b, Variation of SV count in the pan- and core-SV along as additional tomato genomes are incorporated. c, Compositions of the pan-SV and individual genomes. The histogram shows the number of SVs in the 46 genomes with different frequencies. The pie shows the proportion of the SVs marked by each composition. d, Presence and absence information of pan SV across the 46 genomes. Red pentagrams represent published genomes. e, Number of private SVs in wild and cultivated tomatoes, showing a higher abundance of private SVs in wild tomatoes. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Landscape and functional effects of structural variants.

a, Genomic distribution of the SV in relation to the gene. b, SV distribution with respect to transposable elements (TE). c, Frequency distribution of two SVs (upper panel) and three haplotypes (lower panel) on SlHAK gene across 294 wild and cultivated accessions. n indicates the number of individuals per species; d, Na⁺ and K⁺ contents in roots and leaves under salt stress. From left to right panel, Na⁺ and K⁺ contents in roots, Na⁺ and K⁺ contents in leaves for 56 accessions carrying three haplotypes under salt stress. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of accessions per haplotype. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed Student’s t-test. e, Frequency distribution of SVs on known genes across 294 wild and cultivated accessions. n indicates the number of individuals per species.

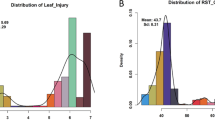

Extended Data Fig. 9 Pangenome assisted gene discovery and functional analysis for grey mold resistance in tomatoes.

a, Phenotype of tomato leaves after B. cinerea infection. The scale bar = 1 cm. b, Frequency distribution of lesion area on leaves of 209 accession after B. cinerea infection. c, Comparison of lesion area on leaves of 209 tomato accessions after B. cinerea inoculation. Scattered colors represent tomato species including 16 wild and one cultivated (SLC and SLL) species. n represent the number of accessions each clade. d, PCR validation of a 937-bp deletion in 24 tomato accessions. Numbers 1-24 correspond to accessions in Supplementary Table 21. Three independent experiments were conducted with similar results. e, Functional domains of SlGMAK were determined using Interpro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) and SMART (https://smart.embl.de/) (upper panel). The putative transmembrane (TM) region was predicted with DeeTMHMM (https://dtu.biolib.com/DeepTMHMM/) (lower panel). f, Expression pattern of SlGMAK gene in various tomato tissues using RNA-seq and RT-qPCR. 20 critical developmental stages (roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits) of MicroTom accession RNA-seq download from NCBI under the BioProject PRJCA001514 (n = 3). Upper right panel, quantitative of SlGMAK gene expression using RT-qPCR (n = 3). g-h, Transient overexpression of SlGMAK in tomato (g) and N. benthamiana (h) leaves. In g, leaves phenotype (left panel), relative expression levels of SlGMAK (middle panel) (n = 3) and lesion area (right panel) (n = 8) on leaves of tomato after B. cinerea infection. In h, leaves phenotype (left panel), relative expression levels of SlGMAK (middle panel) (n = 3) and lesion area (right panel) (n = 7) on leaves of N. benthamiana after B. cinerea infection. Scale bar = 1 cm. i, VIGS of SlGMAK in tomato plants. Phenotype of leaves (left panel), relative expression levels of SlGMAK (right upper panel) (n = 3) and lesion area (right lower panel) (n = 4) on leaves after B. cinerea infection in empty vector (EV) and VIGS-treated tomato plants. The scale bar = 1 cm. In f, g, h and i, all data are presented as mean ± SD with n for the number of biological repeats. Statistical significance was determined by two-sided Student’s t-tests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–3, methods, Figs. 1–23, references and figures.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–25.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 5 and 6 and Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data for Figs. 5 and 6 and Extended Data Fig. 9.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Unprocessed gels for Extended Data Fig. 9d.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, C., Chen, S., Wang, J. et al. A tomato telomere-to-telomere super-pangenome empowers stress resilience breeding. Nat Genet (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-026-02508-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-026-02508-y