Abstract

Progress in understanding the impact of mesoscale variability, including gravity waves (GWs), on atmospheric circulation is often limited by the availability of global fine-resolution observations and simulated data. This study presents momentum fluxes due to atmospheric GWs extracted from four months of an experimental “nature run", integrated at a 1 km resolution (XNR1K) using the Integrated Forecast System (IFS) model. Helmholtz decomposition is used to compute zonal and meridional flux of vertical momentum from ~1.5 petabytes of data; quantities often emulated by climate model parameterization of GWs. The fluxes are validated using ERA5 reanalysis, both during the first week after initialization and over the boreal winter period from November 2018 to February 2019. The agreement between reanalysis and IFS demonstrates its capability to generate reliable flux distributions and capture mesoscale dynamic variability in the atmosphere. The dataset could be valuable in advancing our understanding of GW-planetary wave interactions, GW evolution around atmospheric extremes, and as high-quality training data for machine learning (ML) simulation of GWs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Atmospheric GWs are fast-evolving atmospheric perturbations that dynamically couple the different layers of the atmosphere as they propagate from near the Earth’s surface to high altitudes. GWs are among the key drivers of the meridional overturning circulation in the mesosphere and stratosphere1,2. In the mesosphere, they provide a leading order contribution towards driving the pole-to-pole circulation1,3,4. In the stratosphere, they influence the quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO) of tropical winds5, and the springtime breakdown of the Antarctic polar vortex6. GWs can also contribute to triggering rapid breakdowns of the wintertime polar vortex, i.e., sudden stratospheric warmings (SSWs)7,8, which eventually influence tropospheric storm tracks9,10.

GWs are generated by a myriad of sources (e.g., convection, orography, jets, and fronts) and manifest over spatial scales ranging from \({\mathcal{O}}\)(100) m to \({\mathcal{O}}\)(1000) km. They evolve over temporal scales ranging from few minutes to over a day1. The true impact of GWs on the atmospheric circulation, and how it changes in a changing climate, is not fully understood because of limited global observations and inadequate GW representation in climate models11,12,13,14,15. As a result, most available datasets are believed to underestimate the magnitude of GW momentum fluxes (GWMFs) in the atmosphere, leading to a potential underestimation of their effects on the resolved flow and global circulation.

High-resolution numerical weather prediction (NWP) models and high-resolution climate models, which are computationally prohibitive to run, are increasingly used to simulate GWs at finer-scales and periods not typically captured by observations and reanalyses. As is the case for atmospheric convection, even NWP models typically operating at a horizontal resolution of 5-10 km do not resolve the whole mesoscale GW spectrum. In fact, the optimal model resolution to resolve the complete spectrum of GW interactions is currently unknown, motivating climate modelers to integrate NWP models at increasingly high resolution to generate higher-quality data. In the same spirit, we use the recently generated IFS Experimental Nature Runs at 1 km (XNR1K)16 from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) and compute the GW momentum fluxes. The model, hereafter referred to as “IFS-1km”, simulates global atmospheric evolution at a horizontal resolution of ~1 km for Boreal Winter 2018-2019. The model resolution is at least a factor of 2 higher than any previous global high-resolution simulations conducted to study GWs17,18,19,20,21 or otherwise (2 km global)22, and provides a glimpse into global GW activity in unprecedented detail.

Different modeling studies adopt different approaches to extract GW momentum fluxes from model output. These approaches include applying globally fixed-cutoff high-pass filtering15,23,24,25,26 or a spectrum-based modal decomposition20,27 to separate the planetary and synoptic-scales from the divergent mesoscales and submesoscales. Each approach has its strengths and limitations. The varied methods provide a practical balance between scientific accuracy and computational costs. Here, we employ a Helmholtz decomposition-based approach28,29 to separate the atmospheric flow into rotational and divergent components to obtain small-scale (mesoscale and sub-mesoscale) GW momentum fluxes. The Helmholtz approach, rooted in geophysical fluid dynamics, is believed to be more accurate than fixed-wavenumber high-pass filtering. The approach, however, is computationally demanding. As a rough estimate, the initial cost of computing the GW fluxes using Helmholtz decomposition with existing Python wrappers on the Andes analytics cluster at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF) (olcf.ornl.gov/olcf-resources/compute-systems/andes/) was roughly 500 calendar days. As explained later, we were able to optimize and reduce this cost to a mere 12 calendar days.

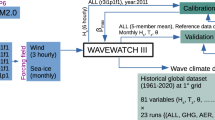

We assess the 1 km model’s capability to resolve the previously unresolved mesoscale GWs using the modern reanalysis ERA530. While ERA5 resolves only part of the mesoscale spectrum, its constrained large-scale dynamics and commendable representation of GW sources and sinks have been leveraged by past studies to advance understanding of atmospheric GWs, their climatology, and compare GW representation in climate models of varying complexity6,15,31,32,33,34,35. We first compare the two datasets for the first week of November 2018, when the model-simulated flow is almost identical to the observed atmospheric flow (reanalysis). We then compare the Boreal winter-averaged momentum fluxes and their distributions in the upper troposphere, lower stratosphere, and middle stratosphere. Finally, we briefly demonstrate how the dataset can be applied to study the tropospheric and stratospheric evolution of GW momentum fluxes around a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event.

The high-resolution flux dataset can be used to study GW evolution in the troposphere and the stratosphere, and more generally, to study interactions between the small-scale and planetary-scale variability in the atmosphere. It could also serve as high-quality training data for ML-based simulators for predicting and representing subgrid-scale GW momentum fluxes in coarser resolution models.

Methodology

The IFS-1km run, used to compute the global GW fluxes using Helmholtz decomposition, is exactly the same as one of the two climate model simulations described and first introduced in Wedi et al.16 and Polichtchouk et al.25,26.

Description of IFS-1km run

The simulation was initialized on 1 Nov 2018 00 UTC from the ECMWF operational analysis and integrated with a time-step size of 60 s at approximately a 1.4 km global grid-spacing using 7999 spherical harmonics. The unprecedented TCo7999 horizontal resolution simulation was performed on the Summit supercomputer, accessed through an Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment (INCITE) award16. The free-running simulation was integrated for four months: November 2018 to February 2019.

The simulation was performed with the full-complexity global semi-implicit semi-Lagrangian spectral ECMWF IFS atmosphere model (based on cycle 45r1; IFS 2018) and forced by the 0.05° OSTIA sea surface temperature and sea-ice data36. The IFS-1km is discretized in the horizontal using a spherical harmonic expansion and a cubic-octahedral grid.

Both deep convection and gravity wave parameterizations are switched off for the 1.4 km simulation; all contributions to the GW forcing, i.e., the wave drag, come exclusively from resolved waves. Grid-scale hyperdiffusion and other numerical method choices in the model reduce its effective resolution from Δx = 1.4 km to about 6Δx–8Δx37,38. Thus, the model resolves the complete mesoscale GW spectrum (wavelengths ≥ 10 km). We use 3-hourly instantaneous fields on model levels to calculate the small-scale momentum flux due to resolved GWs.

Helmholtz decomposition to compute momentum fluxes

The momentum fluxes were computed from the raw model output using Helmholtz Decomposition (HD). Helmholtz decomposition can be used to decompose the horizontal flow into a purely rotational and a purely divergent part. The rotational part is associated with the large-scale balanced flow whereas the divergent part is associated with small-scale GWs. Mathematically, the decomposition can be expressed as:

where (u, v) is the full horizontal flow, ϕ is the potential function such that ∇ ϕ is irrotational, i.e. the curl of ∇ ϕ is 0. Similarly, ψ is the rotational streamfunction function such that ∇ × ψ is non-divergent, i.e., the divergence of ∇ × ψ is zero. Thus, Helmholtz decomposition provides ϕ and ψ which, by applying inverse spectral transforms, could be used to obtain the divergent and rotational parts of the horizontal flow as:

Next, to ensure that the large-scale background is completely removed from the divergent flow, an additional fixed-wavenumber high-pass filter is applied by removing the T21 truncated divergent velocity, (udiv,T21, vdiv,T21), from the divergent flow. This operation is expressed as:

Finally, the high-pass filtered divergent velocities were used to compute the fluxes by multiplying with the eddy vertical velocity (\({\omega }^{{\prime} }\)). \({\omega }^{{\prime} }\) was obtained by removing the zonal mean \(\overline{\omega }\) of the full velocity (ω), i.e. \({\omega }^{{\prime} }=\omega -\overline{\omega }\). The zonal and meridional components of the vertical momentum flux were then computed as:

Here, g = −9.81 m/s2 is the acceleration due to gravity.

Computing momentum fluxes efficiently in Python

Applying Helmholtz decomposition to high-resolution climate model output is computationally prohibitive as it involves applying higher-order spectral operators, like the inverse Laplacian operator, to the spectrally transformed data on a sphere. The time complexity of these operations scales as the cube of the largest resolved wavenumber. For IFS-1km, the largest resolved wavenumber (7999) is unprecedentedly high.

Latency issues

Existing publicly available Python packages, including WindSpharm, can perform the Helmholtz decomposition of low-resolution data quite effectively. Performing the decomposition involves the creation of a WindSpharm object using horizontal velocities. The creation of this Python object then allows performing an array of spectral operations on the data, including Helmholtz decomposition. The spectral operations in Windspharm itself leverage the existing Pyspharm Python package which in turn calls compiled Fortran code to achieve spectral manipulation of the spherical harmonics. As a rough estimate, for a single pressure level for a given timeframe, the WindSpharm library took ~ 14 hours to perform Helmholtz decomposition of the horizontal velocities. Out of the 14 hours, the initial object creation required 7 hours, and the spectral transform of the fields required an additional 4 hours. Therefore, performing the decomposition for the full data (137 levels for 961 timeframes) using out-of-the-box WindSpharm would have required more than 500 calendar days of compute time on 64-nodes job allocations on the Andes supercomputer, making the problem intractable.

Optimizing the momentum flux computations: from intractable to tractable

Making the problem computationally tractable and optimizing for computational resources required heavy optimization of the PySpharm code and the computational workflow. In particular, this involved:

-

1.

Eliminating WindSpharm objection creation altogether and relying on a (much faster) generalized object creation in PySpharm, which does not require horizontal velocities as an input; only the input grid resolution. As a result, the PySpharm object once created can be stored in a file on disk, and simply called separately by each parallel process. Practically eliminating object creation thus led to a massive reduction in compute time.

-

2.

To eliminate computing the spherical transform of the raw gridded data for individual pressure levels in PySpharm before computing the Helmholtz decomposition, the T7999 spherical harmonics were first truncated to T3999 using ECMWF’s software tools, and were directly used to compute the fluxes. Eliminating redundant spherical transforms provided a further boost to the computations.

-

3.

Identifying redundancies in the existing PySpharm function definitions, particularly repeated spectral-to-grid and grid-to-spectral transforms when passing data from one function to another. Removing these redundancies provided a further boost to the overall compute times.

-

4.

Wherever possible, the Python scripts were parallelized (using MPI) for maximum node and CPU resource utilization.

Implementing these four strategies reduced the total time to compute the momentum fluxes in IFS-1km from over 500 days to a mere 12 days. The optimized code was also used to compute momentum fluxes for ERA5 for validation.

Conservative coarsegraining of momentum fluxes

Momentum fluxes carried by atmospheric waves are defined by averaging over single/multiple wave cycles. This removes any phase dependency in flux computations. Thus, the fluxes computed on the native 0.01° reduced Gaussian grid were conservatively coarsegrained to a ~ 2.8° T42 Gaussian grid by averaging the fluxes over wavenumbers 42 and above. The coarsegraining was achieved using the first-order conservative regridding function provided by the xESMF Python library.

Data Records

The data files for the coarse grained momentum fluxes, in netCDF format, can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GX32S39. The high-resolution gravity wave momentum fluxes in netCDF4 format can be accessed at : https://doi.ccs.ornl.gov/ui/doi/475. As shown in Table 1, each file comprises the following variables at 3-hourly temporal resolution: zonal wind (u), meridional wind (v), vertical velocity in pressure coordinates (ω), temperature (T), stratification frequency squared (N2), vertical flux of zonal momentum (\({u}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }/g\)), and vertical flux of meridional momentum (\({v}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }/g\)). The variables have been conservatively coarsegrained from the native 0.01° degree grid to a ~ 2.8° resolution (T42 Gaussian grid). The conservative coarsegraining ensures that the GW momentum fluxes are averaged over multiple wave cycles. The conservative coarsegraining was accomplished using the xESMF regridding package.

A total of 961 records corresponding to the 120 simulated days from 1 Nov 00 UTC 2018 to 1 Mar 00 UTC 2019 period are sequentially stored at 3-hourly resolution in the ten netCDF files, with the first nine files containing 100 records each and the final file containing 61 records. The files are named as: cg_ifs_3hourly_gwmf_helmholtz_ndjf_[01-10].nc.

ERA5 data40 which was used for validation can be freely accessed from the Copernicus data server: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels

Validation by Past Studies

A couple of recent studies15,16,25,26 have tested the realism of an array of atmospheric features in IFS-1km.

Intermodel comparison

Wedi et al.16, who created the model runs, also compared prominent atmospheric features like the zonal mean zonal wind, zonal mean temperature, precipitation, specific humidity profile, outgoing long-wave radiation associated with the Madden-Julian Oscillation, convective storm activity, and the kinetic energy spectrum in IFS-1km, with a well-tested and well-tuned 9 km IFS model control run and an assimilation-constrained ERA5. Their analysis found a strong agreement in the large-scale features among models with varying resolution and parameterizations, and an improved resolution of smaller-scale features including convective storm activity and GW absolute momentum fluxes in IFS-1km. A more rigorous analysis of the mesoscale GW spectrum and their contribution to the zonal mean momentum budget in the tropical and midlatitude atmosphere was the focus of Polichtchouk et al.25 and Polichtchouk et al.26 respectively.

Validation with ground-based observations

Gupta et al.15 conducted a systematic validation of GWs structure and fluxes in IFS-1km across a broad range of datasets, for the 1-15 August 2019 period. The study validated GWs excited over and around the Andes, in both IFS-1km and ERA5, with ground-based observations from an autonomous middle-atmosphere lidar (CORAL). In the vicinity of the Andes, the vertical structure of GWs in both IFS-1km and ERA5 were qualitatively very similar to the GWs observed by CORAL. The horizontal structure of the excited GW packet too was found to be very similar between IFS-1km and ERA5, with IFS-1km resolving an enhanced amount of variability over the 10 km to 300 km spatial scales. Eventually, the model and reanalysis agreed closely with observations for the whole week after IFS-1km initialization. Signs of model divergence appeared only 10-12 days after initialization. With the South American Andes being one of the most prominent GW hotspots for orographic GWs, a strong agreement between IFS-1km and CORAL bears testament to the capabilities of the high-resolution model to skillfully resolve GWs and their lateral propagation in the atmosphere.

It should be noted that, even though increases in model resolution generally improve the GW representation in the model, some biases may still exist among different high-resolution models with different underlying numerics21. These biases, however, tend to become less prominent with increasing resolution.

Lastly, we refrain from any comparisons in the mesosphere, since both IFS-1km and ERA5 include strong artificial damping in the region (above 1 hPa), which leads to scale- and altitude-dependent attenuation of GW amplitudes and structure in the region6,15,21.

Technical Validation

Longer-term GW flux climatology derived from ERA533,41 strongly resemble the climatology derived from AIRS instruments aboard the Aqua satellite in the upper stratosphere42, indicating that an ERA5-based validation of IFS-1km could be informative and insightful. Therefore, here, the GW momentum fluxes from IFS-1km are further validated for the boreal winter 2018 using ERA5. Satellite observations of large-scale winds and temperature are assimilated throughout the troposphere and much of the stratosphere (up to 5 hPa) in ERA5, and thus, the large-scale winds in ERA5 can be treated as close to “observations”. Moreover, both ERA5 and IFS-1km have the same underlying dynamical core ensuring similar numerical representation of the fluid flow equations. While this could mean that both IFS-1km and ERA5 could potentially suffer from the same set of numerical biases, their successful validation using CORAL provides a strong foundation for the technical validation conducted here.

Validation around IFS-1km model initialization: 1-7 November 2018

For the first week of November 2018, the resolved dynamics in IFS-1km model are nearly identical to the assimilated dynamics in ERA5. Therefore, IFS-1km provides an ultra-fine scale account of the GW momentum fluxes in the atmosphere during this period.

The vertical flux of zonal momentum from IFS-1km and ERA5 at four altitudes in the atmosphere is shown in Fig. 1. The zonal winds are very similar between the two models for the four distinct heights (Fig. 1 left vs. right columns; green). The resolved fluxes in ERA5 are significantly weaker than those in IFS-1km, on account of the nearly 30 times coarser resolution. Nevertheless, the momentum flux in ERA5 peaks at the same locations as for IFS-1km. At 10 hPa and 30 hPa, notable hotspots include East Asia, the Andes, the Antarctic Peninsula, and patches over the Southern Ocean. In the upper troposphere-lower stratosphere (100 hPa) and the upper troposphere (200 hPa), the hotspots additionally include the Himalayas, the North American Rockies, and the tropical precipitation systems. This both validates the simulated small-scales in IFS-1km and demonstrates the capability of the dataset to resolve mesoscale fluxes in great detail, significantly more so than ERA515, allowing a more detailed analysis of mesoscale atmospheric variability and its interaction with the large-scale circulation, and around mountains, jet cores, and convective sources.

1-7 November 2018 averaged small-scale vertical flux of zonal momentum, 1000 \({u}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }/g\), for (left column) IFS-1km and (right column) ERA5 reanalysis at three different heights: 10 hPa ~ 30 km, (second row) 30 hPa ~ 25 km, (third row) 100 hPa ~ 15 km, and (fourth row) 200 hPa ~ 12 km. The colors represent the zonal flux 1000 \({u}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }/g\) (units mPa) conservatively interpolated to a T42 Gaussian grid (approx. 2.8° × 2.8°), and the green curves represent the zonal wind with a contour interval of 15 m/s. IFS and ERA5 share the same colorbar for each height. The fluxes in ERA5 are weaker than IFS-1km but have a very similar spatial distribution, demonstrating IFS-1km’s capacity to resolve the waves unresolved by ERA5. The fluxes comprise of contributions from both stationary GWs excited over mountains, and non-stationary GWs excited over other sources including convective systems, jet, fronts, etc. For instance, the South American Amazon rainforest and Southeast Asia are prominent hotspots for convective GW generation in the tropics. The fluxes in this study have not been decomposed into stationary and nonstationary components.

Similar results are obtained from validation of the vertical flux of meridional momentum, as shown in Fig. 2. The degree to which IFS-1km resolves the meridional mesoscale momentum fluxes far surpasses that from ERA5. Yet, the strongest hotspots identified in IFS-1km at all heights match with the strongest hotspots identified in ERA5. We note that some differences in the meridional wind strength exist between the two datasets. These differences become increasingly prominent in the upper stratosphere. At 10 hPa and 30 hPa, these include the southward fluxes (green) over the Andes and the northward fluxes over the Antarctic Peninsula and Ural Mountains. At 100 hPa and 200 hPa, these also include the northward fluxes over the Rockies and Northern Pacific Ocean, and the southward fluxes over the Himalayas.

Same as Fig. 1, but for the meridional flux of vertical momentum, 1000 \({v}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }/g\) (units mPa). The colors represent the flux conservatively interpolated to a T42 Gaussian grid, and the green curves represent the zonal wind with contour intervals of 5 m/s.

Focusing on the troposphere, the zonal mean zonal and meridional fluxes around the tropospheric jet are shown in Fig 3. The zonal fluxes maximize around the jet core. A bulk of these contributions (in the northern hemisphere) can be traced back to storm tracks and convective systems over the Pacific and around the meandering jet over North America (Fig. 1; 200 hPa), which are resolved in more detail in the IFS-1km model than in ERA5. The meridional fluxes, while they do not maximize around the jet, have dispersed sources throughout the longitudinal circle (Fig. 1; 200 hPa) which are resolved with greater clarity in the IFS-1km model.

(a,c) Latitude-pressure profile of the zonal mean zonal component of the vertical momentum flux for IFS-1km and ERA5 respectively, in the troposphere, averaged over 1-7 November 2018. (b,d) Latitude-pressure profile of the zonal mean meridional component of the vertical momentum flux for IFS-1km and ERA5 respectively, in the troposphere, averaged over 1-7 November 2018.

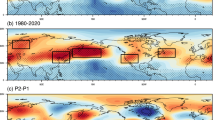

Validation for the whole period: 1 November 2018 - 1 March 2019

We extend the validation to span the whole Boreal winter season. The validation holds even when the time averaging is extended to the whole NDJF Boreal winter season for which the IFS-1km data is available. The spatial distribution of small-scale variability of both zonal and meridional momentum transport in IFS-1km matches that in ERA5 over the ocean, the land, and the maritime continent (comparing the left vs. right column in Figs. 4 and 5). Even for the seasonal average, we note that the meridional wind strength in IFS-1km is found to be weaker than the wind strength in ERA5, likely owing to a weaker-than-observed polar vortex in IFS-1km.

Same as Fig. 1, but averaged over the whole winter season from November 2018 to February 2019. Colorbar limits are different for each subplot.

Same as Fig. 2, but averaged over the whole winter season from November 2018 to February 2019. Colorbar limits are different for each subplot.

Validation of statistical distribution of momentum fluxes

Since the resolved winds and temperature in IFS-1km diverge from the assimilated dynamics in ERA5 ~15 days after initialization in November, comparing the density of the fluxes presents a more stringent validation of the two datasets over seasonal timescales. This is because the GW generation and propagation can be sensitive to the background winds. Since the two models diverge 15 days after initialization, the two models do not resolve identical GWs throughout the winter season. Thus, the distribution of fluxes generated over the whole season from multiple GWs more effectively codifies the small-scale variability in the model.

The global flux density in IFS-1km and ERA5, compared at three different levels in the atmosphere, is shown in Fig. 6. For all three levels, similar distribution shapes are obtained for both the zonal and meridional GW fluxes. However, the magnitudes are different. As would be expected, due to improved resolution, both the eastward and westward fluxes in IFS exhibit a fatter-tailed distribution than ERA5. Moreover, the fluxes in ERA5 are skewed closer to zero, due to which their maximum appears at a slightly lower flux value than in IFS. This is likely due to a combination of two factors: (a) IFS-1km resolves a richer spectrum of GWs than does ERA5, owing to an improved resolution of GW sources (explaining the fatter tail), and (b) for the wave packets resolved by both IFS-1km and ERA5, the fluxes generated in IFS-1km are stronger than those in ERA5 (explaining the systematic shift in maximum). The distribution width gradually shrinks from troposphere (200 hPa) to the upper stratosphere (10 hPa) as the GWs progressively get filtered with altitude.

Histogram illustrating the flux density for cube root of the (left column) zonal momentum flux, 1000 \({u}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }/g\) (mPa), and (right column) meridional momentum flux, 1000 \({v}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }/g\) (mPa), at three different heights: (a)-(b) 10 hPa (~30 km), (c)-(d) 100 hPa (~15 km), and (e) 500 hPa (~5 km). The blue and red histograms in (a,c,e) show IFS-1km and ERA5 fluxes respectively. Likewise, the orange and green histograms in (b,d,f) show IFS-1km and ERA5 fluxes respectively.

Usage Notes

The ultra-high resolution dataset presented here can be valuable for exploring multiple avenues in atmospheric research. We propose some of these avenues in this section.

First, the fluxes from IFS-1km, though limited in time, can be validated with other high-resolution datasets to assess the representation of mesoscale variability across a broad range of convection-permitting models. Recent research has shown key differences in mesoscale representation among a range of sub-10 km resolution global high-resolution models21,43. The root cause of these differences, however, is not fully understood. A more detailed understanding of these differences would also facilitate the development of parameterizations to better represent these processes in coarser-resolution climate models44,45,46,47.

Second, the resolved fluxes provide validated, high-quality data for conducting ML-related research which, for instance, focuses on the development of data-driven subgrid-scale parameterizations for climate models48,49,50. Such ML explorations can benefit from realistic resolved momentum fluxes, as the resolved fluxes (much more so than parameterized fluxes) inherently represent the accurate evolution of GWs in the atmosphere, including the effects of lateral propagation, transient evolution, and refraction of GWs14,41,51. Given the dearth of high-fidelity subgrid-scale data from high-resolution models and observations, our dataset provides an excellent source of model training data to facilitate, for instance, transfer learning experiments using multiple data streams52.

Lastly, inadequate parameterization of subgrid-scale processes prohibits explorations into multi-scale interactions in the atmosphere. That is, how does strong small-scale dynamical interactions influence the large-scale dynamical interactions in the atmosphere and vice versa. This includes mesoscale variability over the Southern Ocean, variability in the vicinity of steep orography, secondary wave generation, among other factors. As a particular example, recent studies have hinted at the potential role of GWs in triggering extreme warming events in the stratosphere by facilitating a rapid breakdown of the strong vortex in the stratosphere, a.k.a., sudden stratospheric warmings (SSWs), and in stratospheric recovery following the breakdown7,8,53. The full extent of the GW interactions with planetary waves in the atmosphere is still not fully understood due to limited high-resolution data. Our data attempts to fill this gap and hopes to inspire more targeted studies. A preliminary analysis, such as shown in Fig. 7 can allow studying the evolution of GW fluxes around stratospheric extremes captured by our dataset (Fig. 7b,c) and allow an in-depth study into the anomalous evolution of GWs around atmospheric extremes (Fig. 7d).

Resolved GW forcing evolution around SSWs. (a) Zonal mean zonal wind evolution at 60°N and 10 hPa for the period 1 Dec 2018 to 28 Feb 2019. (b) Latitude-pressure profile of zonal mean GW forcing due to convergence of vertical momentum, i.e. \({\partial }_{p}\overline{{u}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }}\) (units m/s/day) before the SSW, i.e., averaged over the period highlighted in green in (a). (c) Latitude-pressure profile of zonal mean GW forcing, \({\partial }_{p}\overline{{u}^{{\prime} }{\omega }^{{\prime} }}\), during the major SSW, i.e. averaged over the period highlighted in red in (b). The solid black curves in (b) and (c) show the zonal mean zonal wind using contour intervals 5 m/s during the respective periods. (d) The difference in forcing between strong vortex days (days highlighted in blue and green in (a)) and SSW days (days highlighted in red in (a)).

Code availability

The code to compute the GW momentum fluxes and to conservatively coarsegrain the fluxes, along with the modified PySpharm functions can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GX32S in the python_scripts folder. Raw climate model output from XNR1K at native grid resolution is available at https://doi.ccs.ornl.gov/ui/doi/475. A Stanford Redivis project that allows users to work with the data interactively in a Jupyter notebook environment has been staged at: https://doi.org/10.57761/rc6v-hf22. The default WindSpharm Python package is publicly available at https://ajdawson.github.io/windspharm/latest/, and the PySpharm Python package is publicly available at: https://pypi.org/project/pyspharm/. The xESMF package used for conservative coarsegraining is publicly available at: https://xesmf.readthedocs.io/en/stable/.

References

Fritts, D. C. & Alexander, M. J. Gravity wave dynamics and effects in the middle atmosphere. Reviews of Geophysics 41, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001RG000106 (2003).

Achatz, U. et al. Atmospheric Gravity Waves: Processes and Parameterization. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-23-0210.1 (2023).

Holton, J. R. The Role of Gravity Wave Induced Drag and Diffusion in the Momentum Budget of the Mesosphere. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 39, 791–799 (1982).

Becker, E. Dynamical Control of the Middle Atmosphere. Space Sci Rev 168, 283–314, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-011-9841-5 (2012).

Giorgetta, M. A., Manzini, E. & Roeckner, E. Forcing of the quasi-biennial oscillation from a broad spectrum of atmospheric waves. Geophysical Research Letters 29, 86–1–86–4, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014756 (2002).

Gupta, A., Birner, T., Dörnbrack, A. & Polichtchouk, I. Importance of Gravity Wave Forcing for Springtime Southern Polar Vortex Breakdown as Revealed by ERA5. Geophysical Research Letters 48, e2021GL092762, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL092762 (2021).

Albers, J. R. & Birner, T. Vortex Preconditioning due to Planetary and Gravity Waves prior to Sudden Stratospheric Warmings. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 4028–4054, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-14-0026.1 (2014).

Song, B.-G., Chun, H.-Y. & Song, I.-S. Role of Gravity Waves in a Vortex-Split Sudden Stratospheric Warming in January 2009. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 77, 3321–3342, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-20-0039.1 (2020).

Kidston, J. et al. Stratospheric influence on tropospheric jet streams, storm tracks and surface weather. Nature Geosci 8, 433–440, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2424 (2015).

Domeisen, D. I. V. & Butler, A. H. Stratospheric drivers of extreme events at the Earth’s surface. Commun Earth Environ 1, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00060-z (2020).

Kim, Y.-J., Eckermann, S. D. & Chun, H.-Y. An overview of the past, present and future of gravity-wave drag parametrization for numerical climate and weather prediction models. Atmosphere-Ocean 41(1), 65–98, https://doi.org/10.3137/ao.410105 (2003).

Alexander, M. J. et al. Recent developments in gravity-wave effects in climate models and the global distribution of gravity-wave momentum flux from observations and models. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 136, 1103–1124, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.637 (2010).

Geller, M. A. et al. A Comparison between Gravity Wave Momentum Fluxes in Observations and Climate Models. Journal of Climate 26, 6383–6405, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00545.1 (2013).

Plougonven, R., de la Cámara, A., Hertzog, A. & Lott, F. How does knowledge of atmospheric gravity waves guide their parameterizations? Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 1529–1543, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3732 (2020).

Gupta, A. et al. Estimates of Southern Hemispheric Gravity Wave Momentum Fluxes Across Observations, Reanalyses, and Kilometer-scale Numerical Weather Prediction Model. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-23-0095.1 (2024).

Wedi, N. P. et al. A Baseline for Global Weather and Climate Simulations at 1 km Resolution. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 12, e2020MS002192, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020MS002192 (2020).

Holt, L. A. et al. Tropical Waves and the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation in a 7-km Global Climate Simulation. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 73, 3771–3783, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-15-0350.1 (2016).

Hindley, N. P., Wright, C. J., Hoffmann, L., Moffat-Griffin, T. & Mitchell, N. J. An 18-Year Climatology of Directional Stratospheric Gravity Wave Momentum Flux From 3-D Satellite Observations. Geophysical Research Letters 47, e2020GL089557, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089557 (2020).

Gisinger, S. et al. Gravity-Wave-Driven Seasonal Variability of Temperature Differences Between ECMWF IFS and Rayleigh Lidar Measurements in the Lee of the Southern Andes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 127, e2021JD036270, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD036270 (2022).

Stephan, C. C. et al. Atmospheric Energy Spectra in Global Kilometre-Scale Models 74, 280–299 https://doi.org/10.16993/tellusa.26 (2022).

Kruse, C. G. et al. Observed and Modeled Mountain Waves from the Surface to the Mesosphere near the Drake Passage. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 79, 909–932, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-21-0252.1 (2022).

Fuhrer, O. et al. Near-global climate simulation at 1 km resolution: Establishing a performance baseline on 4888 GPUs with COSMO 5.0. Geoscientific Model Development 11, 1665–1681, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-1665-2018 (2018).

Kruse, C. G. & Smith, R. B. Gravity Wave Diagnostics and Characteristics in Mesoscale Fields. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 72, 4372–4392, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-15-0079.1 (2015).

Kaifler, N. et al. Lidar observations of large-amplitude mountain waves in the stratosphere above Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Scientific Reports 10, 14529, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71443-7 (2020).

Polichtchouk, I., Wedi, N. & Kim, Y.-H. Resolved gravity waves in the tropical stratosphere: Impact of horizontal resolution and deep convection parametrization. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 148, 233–251, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.4202 (2022).

Polichtchouk, I., van Niekerk, A. & Wedi, N. Resolved Gravity Waves in the Extratropical Stratosphere: Effect of Horizontal Resolution Increase from O(10) to O(1) km. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 80, 473–486, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-22-0138.1 (2023).

Žagar, N., Jelić, D., Alexander, M. J. & Manzini, E. Estimating Subseasonal Variability and Trends in Global Atmosphere Using Reanalysis Data. Geophysical Research Letters 45, 12,999–13,007, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL080051 (2018).

Lindborg, E. A Helmholtz decomposition of structure functions and spectra calculated from aircraft data. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 762, R4, https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2014.685 (2015).

Köhler, L., Green, B. & Stephan, C. C. Comparing Loon Superpressure Balloon Observations of Gravity Waves in the Tropics With Global Storm-Resolving Models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 128, e2023JD038549, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JD038549 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Pahlavan, H. A., Fu, Q., Wallace, J. M. & Kiladis, G. N. Revisiting the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation as Seen in ERA5. Part I: Description and Momentum Budget. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 78, 673–691, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-20-0248.1 (2021).

Pahlavan, H. A., Wallace, J. M. & Fu, Q. Characteristics of Tropical Convective Gravity Waves Resolved by ERA5 Reanalysis. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 80, 777–795, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-22-0057.1 (2023).

Wei, J., Zhang, F., Richter, J. H., Alexander, M. J. & Sun, Y. Q. Global Distributions of Tropospheric and Stratospheric Gravity Wave Momentum Fluxes Resolved by the 9-km ECMWF Experiments. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 79, 2621–2644, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-21-0173.1 (2022).

Yang, S., He, X. & Zhu, B. Learning Physical Constraints with Neural Projections. arXiv:2006.12745 [cs] (2020).

Lear, E. J., Wright, C. J., Hindley, N. P., Polichtchouk, I. & Hoffmann, L. Comparing Gravity Waves in a Kilometer-Scale Run of the IFS to AIRS Satellite Observations and ERA5. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 129, e2023JD040097, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JD040097 (2024).

Donlon, C. J. et al. The Operational Sea Surface Temperature and Sea Ice Analysis (OSTIA) system. Remote Sensing of Environment 116, 140–158, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2010.10.017 (2012).

Skamarock, W. C. Evaluating Mesoscale NWP Models Using Kinetic Energy Spectra https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR2830.1 (2004).

Klaver, R., Haarsma, R., Vidale, P. L. & Hazeleger, W. Effective resolution in high resolution global atmospheric models for climate studies. Atmos Sci Lett 21, https://doi.org/10.1002/asl.952 (2020).

Gupta, A. Data for “Gravity Wave Momentum Fluxes from 1.4 km Global ECMWF Integrated Forecast System”. OSF https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GX32S (2024).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present https://doi.org/10.24381/CDS.BD0915C6 (2023).

Gupta, A., Sheshadri, A., Alexander, M. J. & Birner, T. Insights on Lateral Gravity Wave Propagation in the Extratropical Stratosphere from 44 Years of ERA5 Data. Geophysical Research Letters https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL108541 (2024).

Hindley, N. P. et al. Stratospheric gravity waves over the mountainous island of South Georgia: Testing a high-resolution dynamical model with 3-D satellite observations and radiosondes. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 21, 7695–7722, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-7695-2021 (2021).

Stephan, C. C. et al. Intercomparison of Gravity Waves in Global Convection-Permitting Models. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 76, 2739–2759, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-19-0040.1 (2019).

Amemiya, A. & Sato, K. A New Gravity Wave Parameterization Including Three-Dimensional Propagation. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. Ser. II 94, 237–256, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2016-013 (2016).

Eichinger, R. et al. Emulating lateral gravity wave propagation in a global chemistry–climate model (EMAC v2.55.2) through horizontal flux redistribution. Geoscientific Model Development 16, 5561–5583, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-16-5561-2023 (2023).

Kim, Y.-H., Voelker, G. S., Bölöni, G., Zängl, G. & Achatz, U. Crucial role of obliquely propagating gravity waves in the quasi-biennial oscillation dynamics. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 24, 3297–3308, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-3297-2024 (2024).

Voelker, G. S., Bölöni, G., Kim, Y.-H., Zängl, G. & Achatz, U. MS-GWaM: A 3-dimensional transient gravity wave parametrization for atmospheric models (2023).

Espinosa, Z. I., Sheshadri, A., Cain, G. R., Gerber, E. P. & DallaSanta, K. J. Machine Learning Gravity Wave Parameterization Generalizes to Capture the QBO and Response to Increased CO2. Geophysical Research Letters 49, e2022GL098174, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL098174 (2022).

Wang, P., Yuval, J. & O’Gorman, P. A. Non-Local Parameterization of Atmospheric Subgrid Processes With Neural Networks. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 14, e2022MS002984, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022MS002984 (2022).

Mansfield, L. A. et al. Updates on Model Hierarchies for Understanding and Simulating the Climate System: A Focus on Data-Informed Methods and Climate Change Impacts. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 15, e2023MS003715, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023MS003715 (2023).

Sato, K., Tateno, S., Watanabe, S. & Kawatani, Y. Gravity Wave Characteristics in the Southern Hemisphere Revealed by a High-Resolution Middle-Atmosphere General Circulation Model. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences 69, 1378–1396, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-11-0101.1 (2012).

Parthipan, R. & Wischik, D. J. Don’t Waste Data: Transfer Learning to Leverage All Data for Machine-Learnt Climate Model Emulation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.04001v2 (2022).

Wicker, W., Polichtchouk, I. & Domeisen, D. I. V. Increased vertical resolution in the stratosphere reveals role of gravity waves after sudden stratospheric warmings. Weather and Climate Dynamics 4, 81–93, https://doi.org/10.5194/wcd-4-81-2023 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by Schmidt Sciences, LLC., a philanthropic initiative founded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt, as part of the Virtual Earth System Research Institute (VESRI). AS acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation through grant OAC-2004492. The 1.4 km IFS runs were performed using resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF), which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725. The authors thank Brian Chivers at Stanford's Doerr School of Sustainability for building the Redivis project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The nature run experiment(s) were performed by Inna Polichtchouk and Nils Wedi (ECMWF) on the Summit Supercomputer at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. A.S. and A.G. conceived the computation methodology, V.A. provided the data and the computing resources, and provided valuable contributions towards optimizing the momentum flux computations. A.G. performed the computations on the model output. A.S. and A.G. analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, A., Sheshadri, A. & Anantharaj, V. Gravity Wave Momentum Fluxes from 1 km Global ECMWF Integrated Forecast System. Sci Data 11, 903 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03699-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03699-x