Abstract

Understanding how species interact within ecological networks is essential for predicting the consequences of environmental change, from trophic cascades to broader changes in species distributions and ecosystem functioning across large spatial scales. To facilitate such explorations, we constructed trophiCH: a country-level trophic meta-food web (henceforth “metaweb”) that includes vertebrates, invertebrates, and vascular plants within Switzerland, based on literature published between 1862 and 2023. Our comprehensive dataset catalogues 1,112,073 trophic interactions involving 23,151 species and 125 feeding guilds (e.g., fungivores). Thirty percent of species-level interactions were empirically documented. Additional species-level interactions were inferred by resolving coarser taxonomic records (e.g., inferring links from “species A feeds on genus B”) based on habitat co-occurrences. While explorations of large-scale food webs have often relied on modelling approaches due to data gaps, this empirically based metaweb paves the way for data-driven studies of real-world food webs across space and time. By integrating the metaweb with local species assemblages knowledge, future studies can gain insights into broad patterns of food web structure across spatial scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Species responses to perturbations have often led to a modification of their geographical distribution1 and abundance2. Moreover, species are interacting with each other through complex ecological networks in multi-species systems3 and are thus additionally exposed to biotic filters that determine the overall response of an ecosystem to perturbations. Consequently, to study the distribution of biodiversity in space and time and flux-associated ecosystem functions (e.g., pollination, herbivore regulation)4, a food web approach is a powerful way to describe complex biological communities, taking into account species richness, composition and the fluxes of biomass and energy between them5. Yet, the diversity of these biological communities, their associated ecosystem functions, and the efforts to maintain them operate at different spatial (local, regional and global)6,7,8,9 and temporal10,11,12,13,14,15 scales.

Recent work has demonstrated that the structure and function of food webs vary across environmental gradients at large spatial scales, e.g. along latitudinal, climatic and resource availability gradients16,17,18,19,20,21. Additionally, the dynamics of network structure in mutualistic plant-animal interactions has been demonstrated to vary depending on the temporal scale22. Nevertheless, our understanding of how and why ecological networks vary in space and time remains in its infancy, partially due to a shortage of existing interaction datasets and the challenges of comparing differently built food webs16. One of the primary hurdles in expanding our understanding of food webs beyond the local scale is the inherent difficulty in collecting empirical data on trophic interactions. The collection of occurrence data alone is costly, time-consuming, and requires taxonomic expertise. The added complexity of observing species in their natural habitats and waiting for trophic interactions to occur—possibly across multiple seasons and life stages—complicates the challenge. Designing and implementing a standardised procedure across habitats and regions to document spatial and temporal variability is unrealistic, given the prohibitive requirements for effort and financial costs. This underscores the necessity for innovative methodologies in the study of ecological networks beyond the local scale.

A meta-food web (henceforth “metaweb”) aggregates all potential trophic interactions between all species that co-occur within a region23,24,25. Local food webs inferred from the metaweb can be considered subsets, similar to how local communities are assembled from a regional species pool24. The metaweb approach presents an efficient tool to standardise the comparison of food webs across spatial and temporal scales, and exponential growth in computational power and data collection has popularised the approach in the last five years26. Metawebs represent a major step towards understanding complex food web patterns that go beyond the local and the contemporary context26. Yet, this larger scale returns the ecologist to the original problem: data gaps are much more evident when regional pools include potentially thousands of species.

In the face of these large gaps, predictive models based on phylogenetic27 or morphological28 traits may provide an alternative approach. It has long been demonstrated that models based on simple parameters can build complex food webs which are comparable to empirical food webs29. For instance, in aquatic systems, body size can be a strong predictor of feeding interactions, and this relationship has been exploited to create the global marine fish metaweb28. While such models are useful tools to simplify complex ecological systems, they must be calibrated against empirical data26, which can be difficult for already data-deficient regions, taxonomic groups, or interaction types. Additionally, they may not fully capture the complexity, idiosyncrasies, and emergent properties of real-world ecosystems30, presenting a need for an empirically based understanding of food webs across space and time.

Empirical metawebs have been constructed across large scales in Europe20,24,31,32,33 and elsewhere34,35, demonstrating spatial variations in network structure across elevational20, climatic36 and anthropogenic31 gradients. These metawebs have been generally limited to bitrophic networks (those including two trophic levels of species, such as plants and their pollinators, or parasitic wasps and their hosts) or well-studied guilds, such as tetrapods, which only account for a small fraction of trophic links in the web of life. Plant-animal trophic interactions are one of the primary ways taxa are interconnected in ecosystems37, but remain unaccounted for in large-scale studies in Europe—except for some specific taxonomic groups31,38. A metaweb that connects the multiple taxonomic groups co-existing in a region by their trophic interactions enables us to integrate species-habitat dependencies with the additional species-species dependencies. Building such a metaweb requires extensive knowledge of species occurrences and their interactions in a defined geographic region.

Historical records of species occurrences are extensive and well-archived for Switzerland, a small country located in central Europe with an area of approximately 41,000 km2. Of the nearly 86,000 multicellular species estimated to occur within the country, around 56,000 have been identified39, with the spatial distribution of around 10,000 of these species being well-documented40. Combining these observations with a method for inferring interaction networks based on geography41 can allow for the compilation of a comprehensive food web for Switzerland. This approach has already been implemented for some guilds (birds, orthopterans, lepidopterans and plants)20 by making the following assumption: if two species have been observed to interact elsewhere, the interaction may also be realised if they co-occur within a spatially confined unit. The assumption fixes the diet breadth of a species across the entire metaweb without accounting for intraspecific diet variation driven by biotic42,43,44,45,46 and abiotic47,48 factors. We emphasise that the nature of the metaweb approach creates a network of all potential links between the target species. This is, in fact, an overestimation of any species’ diet breadth at any one point in space and time. We refine this inference approach41 by only including potential links for documented interactions with known co-occurrence within the region (Switzerland) and by further trimming inferred interactions based on species’ habitat associations. Additionally, local food web structure has been demonstrated to be influenced more by the assembly process than local dynamical processes49. Thus, by restraining interactions by species ecology (habitat associations), distribution, and the assembly process, local food webs inferred from the trophiCH database remain within a “realistic boundary” of potential interactions20 while forming comparable local food webs built from the same metaweb.

Here, we provide the trophiCH dataset, an empirically based species-level metaweb for 26,243 taxa (including vertebrates, invertebrates, and vascular plants) in Switzerland and 1,188,063 links between them. Of these, 1,107,253 interactions between 23,002 taxa are resolved to the species–species level (Fig. 1a,b). This metaweb is based on data extracted from 732 sources of scientific and grey literature (published papers, books, voluntary websites, etc.). For some taxa, we additionally used a spatial model based on simple parameters (co-occurrence in the same habitats and vertical strata) to infer trophic information from the genus and family levels to the species level. We provide the species list used in this study along with information on the associations of these species with habitats and their vertical strata in those habitats. We provide a dataset including reference metadata, such as the full citation, publication date, location, accession, and data collection methods for each reference.

Distribution of species, interactions and data gaps within the metaweb. (a) The distribution of taxa covered by the empirical and full metawebs, (b) the distribution of interactions in the empirical and full metaweb, separated by interactions between plants, invertebrates and vertebrates, and interaction types (herbivory, pollination, parasitism, predation and other interactions missing information on interaction types). (c) the distribution of data gaps in the metaweb by broad taxonomic groups, separated by species missing diets and species missing predators. Icon attribution: Flaticon.com.

Our multi-taxa metaweb is an archive of potential interactions that may occur between species, if they co-occur within the confines of our region: Switzerland. When combined with high-resolution occurrence data, it can infer more localised networks, which can be used to facilitate comprehensive large-scale explorations across Switzerland40. As such, structural and topological properties of food webs (such as connectance50, modularity51, nestedness52, etc.) can be compared across environmental gradients (such as precipitation, land-use intensity, temperature, etc.)16,25. For example, the trophiCH metaweb was combined with existing classifications of species’ associations with biogeographic regions to predict twelve regional multi-habitat biogeographic food webs53. By additionally utilising the habitat-associations presented in this present data descriptor, the robustness of these twelve food webs to different types of sequential species extinctions due to habitat loss were assessed, demonstrating elevational differences53. In another example, aquatic and terrestrial communities were first sampled using environmental DNA along an urbanisation gradient in the city of Zurich, Switzerland. By combining the trophiCH metaweb with the sampling results, 54 local site-level food webs were inferred, and used to demonstrate that combined aquatic and terrestrial food webs become decoupled and more homogeneous along an urbanisation gradient54. In yet another case, the trophiCH metaweb was combined with species distribution models (SDMs) to build nearly 18,000 catchment-scale food webs across Switzerland55, each representing a spatial resolution of ca. 2 km2. Local species assemblages for river sub-catchments were first inferred using SDM-based catchment-scale presence-absences, and food webs were built by inferring that species co-occurring within the catchments and sharing trophic interactions within the trophiCH metaweb would inherit the interactions at the catchment scale55. This study not only demonstrated that catchment-level food web properties were shaped by land use and elevation, but also combined SDM outputs and trophic interaction data to develop a metric of habitat connectivity accounting for species’ resource availability55. Other such potential large-scale, high-resolution studies of environmental gradients are especially relevant in the face of a recent publication of a 25-m resolution multi-raster dataset at the country-scale for Switzerland, covering environmental variables across topographic, bioclimatic, edaphic, land use and vegetation categories, among others56.

While most existing metawebs have only been used to study spatial variation20,25,28,31,32,34,47,57,58,59,60 (with some exceptions21,33), by incorporating temporally explicit data as such available in Switzerland61, it may be possible to study the temporal dynamics of these local networks. In the face of gaps in data needed to infer local networks, the metaweb itself can still provide crucial information on the topography of the regional food web. For example, robustness analyses simulating real-world perturbations (such as the loss of species or of interactions)18,62 on threatened habitats across the multi-habitat metaweb could provide an understanding of how habitat-specific losses could influence food web structure and stability. Utilising the entire metaweb could enable us to also consider variations in dietary preferences within species to identify the potential of rewiring the food web, which could lead to new interactions that may only occur in the future as species distributions shift. Metawebs have also been used to predict not only local networks, but also entire metawebs in similar biomes63, and the Swiss metaweb may be a first step towards a multi-trophic food web for other European countries, or even the whole of Europe. Finally, the metaweb can be used for Swiss-scale conservation measures. For example, graph-theoretic topological metrics, such as betweenness or closeness centrality64, can be used to identify key species for conservation.

Methods

Checklist of species

We compiled a checklist of animal species based on existing literature for Arachnida40,65,66, Diplopoda67, Entognatha (Diplura68). Insecta (Coleoptera69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88, Dermaptera68, Diptera89,90, Ephemeroptera91, Hemiptera92,93,94,95, Hymenoptera68,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105, Lepidoptera40,106, Mecoptera68, Megaloptera107, Mantodea107, Neuroptera68, Odonata108, Orthoptera109, Plecoptera91, Raphidioptera68, Strepsiptera68, Thysanoptera68, Trichoptera91 and Zygentoma110), Crustacea (Amphipoda111,112,113,114,115 and Decapoda116), Mollusca117 and Vertebrata (Hyperoartia118, Actinopterygii118, Amphibia40, Aves119, Mammalia120, Reptilia40). For plants, we used the Tracheophyta121 checklist of Switzerland. We predominantly used federal checklists, supplemented by continental checklists where data were lacking, as follows. For a checklist of Swiss aphid parasitoids, we selected a subset of the checklist of the Aphidiinae of the Czech Republic104, which was validated by a local expert (see: Acknowledgements). The existing Chrysididae103 checklist was similarly validated, as significant changes had been made since the publication of the previous list in 1997. In total, this checklist consisted of 24,039 species. We emphasise that this checklist is not meant to be used as a comprehensive checklist for each family presented here but includes all the species for which trophic and/or occurrence information was available. For example, for some families, such as Chrysomelidae (Coleoptera), we only include an incomplete set of species known to occur in Switzerland (334, in comparison to 399 species according to GBIF records122, or potentially 86%). Our aim was to include as many well-documented species as possible, especially for groups, such as Chrysomelidae, where validated checklists may be missing, but trophic information is readily available.

Literature-based data search and extraction

We systematically searched for primary literature and datasets using the Google Scholar123 and Google Dataset Search124 engines, respectively, and for books using swisscovery, the Swiss platform for sharing scientific information between around 500 libraries125. We used every combination of the following search queries: taxonomic names at the order, family, and genus level (for animals), the ecological terms “trophic”, “diet”, “prey”, “predator”, “host”, and “interaction”, and the spatial terms “Switzerland”, “France”, “Germany”, “Austria”, “Italy” and “Europe” (the regions surrounding Switzerland). We included 305 unique sources from books66,94,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,108,109,111,116,118,120,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262, primary literature18,24,25,92,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331,332,333,334,335,336,337,338,339,340,341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375,376,377,378,379,380,381,382,383,384,385,386,387,388,389,390,391,392,393,394,395,396,397,398,399, and existing databases400,401,402,403,404,405,406,407,408,409. Pairwise species interactions between the resource and consumer taxa were additionally filtered to include only taxa present in our Swiss checklist.

For larger databases, specific approaches were needed for further extraction. For birds, we directly consulted the institutional website of the Swiss Ornithological Institute410 by searching species names and manually extracting diet information from the “food” section of each species page. For the GloBI database, we downloaded stable version 0.3411. We included only the rows in the taxonomic names in the columns “sourceTaxonName” and “targetTaxonName” which matched the taxonomic names in our checklist of taxa. We additionally only included interactions from the “interactionTypeName” columns which matched the following terms: “visitsFlowersOf”, “parasiteOf”, “parasitoidOf”, “eats”, “visits”, “pollinators”, “hasHost”, “mutualistOf”, “preysOn”, “ectoparasiteOf”, “kleptoparasiteOf”, and “endoparasiteOf”. For the Animal Diversity Web405, we used the associated Quaardvark tool412 to extract the data. With regards to the query “What groups of animals are you interested in searching?”, we chose for the “Animal Group” selection the kingdom “Animalia” and for the “Geographic Range > Biogeographic Regions” selection the term “Palearctic”. For the report on “What do you want to know about them”, we choose the taxonomic rank of “Species”. In the “Habitat” selection, the following terms were included: “Terrestrial Biomes”, “Aquatic Biomes”, “Wetlands”, and “Other Habitat Features”. For the “Food Habits” selection, the following terms were included: “Primary Diet”, “Animal Foods”, “Plant Foods”, “Other Foods”, “Foraging Behavior”. Additionally, from the “Predation” selection, we chose the “Known Predators” option. From the resulting dataset, we excluded all interactions with taxonomic terms which were not present in our checklist. For the “freshwaterecology.info” database403, we searched under the “Macro-invertebrates” sub-section as follows: First, we selected all taxa listed in the “Taxagroup” section and searched for all information on the ecological parameter “feeding type”413, based on the Moog (1995) classification414. Of the ten terms, the term “other feeding type” was discarded. For “grazers/scrapers” we translated this to include the feeding guilds “Algae”, “Detritus” and “POM” (particulate organic matter), “miners” were translated to include “Algae” and “Plantae”, “xylophagous taxa” (feeding on woody debris) were translated to the term “Detritus”, “shredders” were translated to include “Plantae”, “POM” and “Detritus”, “gatherers/collectors” were translated to “POM”, “active” and “passive” filter feeders were translated to “POM” and “Microprey”, while “predators” and “parasites” were translated to “Animalia”, while the Interaction_Type column specified whether this referred to “Predation” or “Parasitism”.

Following an initial validation of data completeness (see: Technical Validation), we conducted a secondary search for additional interaction information, focusing on species with no data identified in the preliminary search. This involved targeted Google searches using the species name in combination with the following terms: “diet,” “food,” “prey,” and “host”, and limiting our search to the first search page. These searches led us to 53 additional sources, including naturalist websites, species fact sheets, and voluntary science platforms.

For many invertebrates, we used BugGuide415, by searching the missing species names and manually extracting diet information from the “Diet” section of each species page. For other taxa, additional sources were accessed directly through the targeted Google searches, including websites from Wikipedia416, the Woodland Trust417, the National Wildlife Federation418, the Australian Faunal Directory419, the Aquatic Insects Key420, Natura Bohemica421, Lepidoptera and other life forms422, Pyrgus423, the UK leaf and stem mines of British flies and related insects424, Animalia425, Encyclopedia of Life426, Artsdatabanken427, the Plecoptera Species File428, the UK Beetle Recording429, the Penn State Agronomy Guide430, the University of California Case Histories Biological Control Project431, Project Hypersoil432, Influential Points: Statistics and Aphids, things that bite and suck433, Lepidoptera Mundi434, LepiWiki435, the Moths and Butterflies of Europe and North Africa436, info fauna437, Microlepidoptera: Atlas van de kleine vlinders in Nederland438, Association Papillons de France439, The Reptile Database440, Soil Ecology Wiki441, ThripsWiki442, Trichoptera Ireland: the distribution and autecology of caddisflies (Trichoptera) in Ireland443, UK Beetles444, Wiki der Arachnologischen Gesellschaft445, the Online Database of Afrotropical Moth Species446, Bee-Finder447, British Bugs: an online identification guide to UK Hemiptera448, the Bees, Wasps & Ants Recording Society449, Chrysis.net450, Butterflies & Moths of Palaearctic Regions451, Beetle Fauna of Germany452, Lepi’Net: Les Carnets du Lépidoptériste Français453, The Atlas of Common Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Eastern North America454, Heuschrecken-Wiki455, Schmetterlinge der Schweiz - Butterflies & Moths of Switzerland456, The Sawflies (Symphyta) of Britain and Ireland457, Spektrum458, Thrips-iD459, UKmoths460, Wildbienen461, Faszination Wildbienen462, Insektenbox463, Life in Freshwater464, Meadowia465, and Naturspaziergang466. As individual species pages and content authors varied across these platforms, we recorded the specific URL for each source page directly within the references meta-dataset (see: Data Records). Each interaction derived from one of these websites is therefore linked to its exact source page in the dataset, even though only the main website URLs are cited in this data descriptor. Data collection, extraction and archival occurred between January 2021 and October 2023. The temporal range of the covered resources were from 1862–2023.

We extracted digital data, when possible, using an automated pipeline in R467 (version 4.3.2) and RStudio468 (version 2023.12.1) and saved them as comma-separated files. Books and other analogue data were extracted through manual input into comma-separated files. We primarily recorded resource and consumer names and their taxonomic ranks, then we translated German and English names into scientific names, where applicable. Where available, we gathered additional information on associations to a species’ habitat and to a position in the vertical stratification of the ecosystem, on their life stages, and interaction type. Broad non-taxonomic diet information (e.g., detritivory) and diet information on non-focal taxa (e.g., fungi) were recorded and standardised into 125 specific feeding guilds. These also included some arthropod families (mostly ill-studied dipterans and beetles) for which higher-resolution data were unavailable. All datasets were merged into one large comma-separated file (henceforth raw dataset)469. The raw dataset consisted of 442,599 interactions between 22,862 taxa, based on 655 unique references. Of these, 364,136 interactions were documented between 16,907 species (Fig. 1a,b). All detailed references for the interactions are provided as a meta-dataset.

Taxonomy-based inference of interactions

While the raw dataset included many species-species interactions, many other interactions were recorded with the consumer taxa at higher taxonomic levels. However, it has been demonstrated that varying node resolution within observational ecological networks can modify network topology metrics470. Additionally, our raw dataset included many hierarchically nested interactions, such as genus A and species B eating species C, wherein species B is within the genus A, creating artificial interaction redundancies. Thus, to retain metric reliability in future analyses of the metaweb without losing potential trophic data (as some species only had low-resolution resource information) and to reduce some redundancy of interactions, we implemented further strategies to increase the taxonomic resolution of the metaweb (Fig. 2, see below).

Construction and expansion of the metaweb. (a) Initial compilation of a species checklist, as well as their upstream taxonomic information for genera and families, and creation of feeding guilds, such as fungi. (b) Empirical data collection process, focusing on information at the species, genus and family level. (c) We expanded links where species were known to consume an organism at the genus level to include all species within the genus (link 1). We additionally inferred links where species were known to consume an organism at the family level, for generalist predators, and filtered by their associations to habitat and vertical stratum within the environment (link 2). Links were also inferred where it was explicitly known that a family of organisms were generalist feeders on feeding guilds, such as fungi (link 3). (d) A final metaweb is assembled using all empirical and inferred links. Icon attribution: Flaticon.com.

We initially followed the approach used by Maiorano et al.24: if a species was described as consuming species from the family level or higher, all species within the described families were considered as potential prey. While a valid approach for tetrapods, this approach can be problematic when considering interactions between insects and plants. Phenotypic variation within families of insects, which at times include hundreds, if not thousands of species, is higher than within tetrapod families. Thus, we restricted such taxonomy-based inferences to the genus level (Fig. 2, link 1). Some family-level inferences were allowed for pollinators, but only if empirical records explicitly confirmed the species to be polylectic. The remaining genus-level information was retained in the metaweb at the lower taxonomic resolution.

The species-level trophic interactions within the raw dataset contained a strong bias towards well-studied specialist taxa, especially for primary consumers such as lepidopteran larvae. In contrast, the diets of generalist consumers such as spiders were often only classified to the family level or higher. To better account for the generalist predators in the metaweb, we implemented an empirically based interaction inference strategy based on co-occurrence in the habitat and vertical stratum within ecosystems (see: Habitat and stratum associations). Firstly, all families within the checklist containing only generalist predator species were identified. For species within these families, documented information on their prey at the family level was first used to infer interactions from the predator species to all species within the family. Subsequently, we removed interactions in which the resource and consumer species do not potentially share habitats and vertical strata within the habitats (see: Habitat and stratum-associations and Fig. 2, link 2).

In cases where families have been documented to be generalised consumers of taxonomic groups that are absent from the metaweb but present in the form of feeding guilds, we inferred links between all species within the family and the feeding guilds. For example, all larvae of the Platypezidae fly family feed on fungi403. Since we grouped all fungi into the basal feeding guilds “Fungi” within the metaweb, all Platypezidae species known to occur within Switzerland were thus connected to the node “Fungi” (Fig. 2, link 3). In this way, information on the predators of Platypezidae species did not have to be aggregated to the family level.

Habitat-association and position in the vertical stratification of the habitat

We define the habitat associations of each species according to nine classes in the broadest of the TypoCH471 habitat classifications. The habitat information was collected in two different ways. Firstly, we collected it along with interaction data where available. Secondly, we inferred habitat associations by intersecting species occurrence data40 with the Habitat Map of Switzerland472. We used the st_intersection() function from the sf package473,474 (version 1.0–15) to intersect the point data with the polygonal habitat map. The output provided occurrence counts per species and habitat. We retained all habitat associations with at least 100 counts, as well as associations that had also been documented in the literature survey. Then, we classified all species with three or more habitat associations as habitat generalists and all species with less than three as habitat specialists. We justify this as species with two habitat associations may still be specialists, where different life stages may have high habitat specificity. For habitat generalists, only habitat associations with occurrences above the median of total occurrences were retained, others were dropped. For habitat specialists, habitat associations were only retained if the species was documented at least five times within that habitat. We obtained 6,818 habitat associations based on the Habitat Map and 3,062 based on observational data. For the remaining species, we inferred habitat associations. Firstly, for species where habitat associations were missing, we first combined all known habitat associations of all species within the same genus. We only retained the habitats shared by the median number of species within the genus or higher and assigned these to the species where habitat data were missing. Thus, we were able to infer habitat associations for all species; 18% of plant species habitat associations were inferred at the genus level. For animals, this genus-level inference created habitat associations for 16% of all animal species. A similar inference was made for another 51% of the animal species habitat associations, but using aggregated family-level habitat associations, as genus-level inferences were not possible due to gaps in data.

We defined the incidence of each species according to the following strata within a habitat: on ground or in leaf litter, on vegetation, in ground, in water, on host, in dwellings, in air, in host nest, in vegetation, on fungi, in caves. While most of these classes refer to the position in the vertical stratification, some, such as “in vegetation” were included to separate free-living species which can feed on multiple organisms, from species which living within a plant, and thus would not be available as a potential resource for an organism only feeding on the outside of the vegetation. This information was collected along with interaction data for 10,360 animal species (as well as for relevant genera and families if species-level information was not available). All 3,775 plant species were classified according to the Raunkiær plant life-form classifications in Flora Indicativa475. Plants classified as hydrophytes or pleustophytes were classified as “in water”, epiphytes were classified as “on vegetation”, and all others were classified as “on ground or in leaf litter”, “in ground” and “on vegetation”, the latter such that inferences could be correctly made between animals classified as “on vegetation” and vegetation. Where information was unavailable, species-level characteristics were inferred using the same methods as for the habitats, first at the genus level (3,886 species) and then at the family level (6,119 species). Thus, 49% of animal associations to vertical strata in their habitats were inferred from family or genus-level information.

Data Records

We provide all data and scripts469 on Envidat, the Swiss data portal for environmental monitoring and research data. We provide six datasets: 1) the metaweb, 2) the taxa checklist, 3) the data source meta-dataset, 4) the list of generalist basal and predator families and polylectic species with citations and 5) a dataset with citations for the inferences of missing predators and 6) a dataset with citations for the parallel inference of diets from similar species (see: Data completeness). The metaweb is a pairwise interaction dataset, with each row representing a potential interaction (see Table 1 for all column information). This dataset includes the taxonomic names, ranks and life stages (where available) of each species in the interaction. Moreover, we provide a numerical identification (Citation) column for the citation, which relates to the full citation information provided in the resource metadataset. We additionally include information on the level of inference by taxonomic expansion (see: Taxonomy-based inference of interactions), as well as information on further details on the type of interaction, such as predation, parasitism, or pollination, where available. The taxa checklist provides our list of species and feeding guilds, upstream taxonomic information, and their associations with habitats and vertical strata within habitats (Table 2). For each citation number, the resource meta-dataset contains a full APA-style citation, information about the data source and the methods used to collect the datasets, a stable accession, as well spatial and temporal information about the data collection (Table 3). Additionally, we include a dataset listing the taxa for which the diet breadth was broad, for families of predators and those using feeding guilds as resources, and for polylectic species, along with a citation ID for the relevant citations (Table 4). We provide a dataset listing the families for which predators were missing, and inferred based on broad data, with accompanying citations (the structure of this dataset is identical to Table 1, except it is missing the column named “Inference”). Lastly, we provide a list of species for which diet information was inferred based on taxonomically similar species, with references validating their similarities in diet (Table 5).

Technical Validation

Data collection

We aimed to estimate the human error arising from manual and automated data extraction (Fig. 3). We first classified the data as originating from either analogue or digital sources. Analogue sources include data which were manually transcribed into comma separated values. Digital sources include data which were received as data tables or matrices, where the transformation to the standard data table format was automated through scripts in R. Since we processed digital sources automatically, we assumed the error rate to be either very high or close to zero. Thus, five random samples (or the maximal possible number if the data sources included fewer than five samples) were validated for each digital dataset (Fig. 3). One error was discovered due to an error in the script, which was corrected, such that the error rate was refactored to be 0 for the digital sources.

Validation of the data extraction process. The diagram outlines the sequential steps, beginning with the division of raw datasets into analogue and digital data, then random sampling, error checking, and consolidation across multiple data sources, culminating in the Wilson Score Confidence Interval computation.

For analog sources, we aimed to estimate a (Wilson score) confidence interval of the error rate. To achieve a 95% confidence level (z = 1.96), with a margin of error e = 0.01, and an estimated error rate p = 7%, the required size of the random sample was of n = 2501, based on the following approach: \(n=\,\frac{{z}^{2}p(1-p)}{{e}^{2}}\). The estimated error rate was based on the validation approach of the European tetrapod metaweb24, which estimated a base error rate of 6%. We then randomly sampled 2501 data points and validated them as follows: if the data point had been further confirmed by at least one other data source in the metaweb, it was assumed to be correct (Fig. 3). For all other data points in the sample, we manually checked each source and discovered three errors in total, all of them single-entry errors. The error rate for the analogue data sources was thus computed to be between 0.04% and 0.35% (95% CI). This validation was conducted in Python (v. 3.11.4)476 using numPy (v. 1.25.1)477, and pandas (v. 2.0.3)478.

Data completeness

To assess the extent of data gaps, we checked whether trophic chains were truncated by comparing true basal and apex taxa to those appearing as such within the metaweb. True basal taxa were identified as vascular plants and non-animal groups (such as detritus) within the feeding guild classes (3,903 taxa). True apex taxa were classified as apex predators and parasitic arthropods of apex predators (1,018 taxa). We additionally identified taxa for which the only trophic information was a self-loop, in essence, obligate cannibals. The raw network topology revealed that 2,170 species were improperly in an apex predator position (due to missing outgoing links), while another 5,581 species were improperly in a basal position (due to missing incoming links).

We focused on filling these gaps for species for which spatial data are readily available, as many other species for which information is lacking are less well-studied. Moreover, we aimed to cover generally well-studied groups completely, such as tetrapods. To this extent, we conducted broader internet searches to obtain information from secondary and grey literature sources, such as voluntary scientists and insect enthusiasts (see: Literature-based data search and extraction). For seven species (the slow worm, five orthopterans and one caddisfly), predator information was present while diets were missing. Their diets were inferred based on the diets of ecologically similar species, after confirmation in the literature with regards to the similarities in diets. Additionally, for one species of spider, the predators were inferred based on the predators of an ecologically similar species. Many families of arthropods were additionally missing information on predators. In a few cases, such as with wood beetles, we inferred the predators of the species in these families to generalist predator families such as woodpeckers, or inferred predators of diplopods based on broad information such as, “hedgehogs feed on diplopods”, to hedgehog species being connected to all diplopod species within the same shared habitat. Some trichopteran predators were inferred based on the fish predators most commonly shared by other trichopterans. This approach was also applied to amphipods missing predators based on amphipod-eating fishes and birds, as well as decapods based on decapod-eating fishes and birds. In these cases, the interactions were further trimmed by habitat and vertical stratum. Each case is documented by an accompanying citation and classification in the “Inference” column such that this uncertainty can be accounted for in future usage (see also, Code Availability: 02_inferring_interactions_special_cases.R for more detail on all such special cases). After this correction, we recovered diet information for 1,221 species and predator information for 574 species. Nonetheless, 4,298 species do not have any diet information, while 1,594 species have no predator information. These gaps shine a light towards potential future lines of research. We additionally view the identification of these gaps as a starting point for future contributions to the trophiCH database. While the current version of the metaweb is static, we welcome researchers with interaction data—particularly for understudied taxa or ecological groups like beetles and dipterans (Fig. 1c)—to contact the corresponding authors if they are interested in contributing to future updates or extensions of the dataset, or to correct/validate the modelled interactions.

Comparison to other empirical metawebs

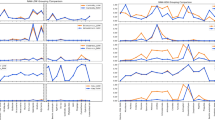

We compiled a list of eighteen existing empirical metawebs31,32,33,479,480,481,482,483,484,485,486,487,488,489 to facilitate a relative comparison to the data coverage of our metaweb (Supplementary Information Table S1). We focus on total degree, which considers the sum of each species’ in and out links in a network. We calculated the mean of the sum of all species’ total degrees to consider the data coverage, and the standard deviation of the mean. These metrics are likely to depend on the spatial range of the network (some metawebs were limited to one city while others were global) and species richness, as well as random or sampling effects, and therefore cannot be robustly compared across networks16. To control for these spurious effects, we modelled the co-variation of network properties with linear regression and compared residuals of the metrics16,50. We fit linear mixed effects models to predict relative mean total degree and its standard deviation based on relative species richness, treating the type of network (bitrophic or multitrophic) as a random effect. We used the lmer() function from the lme4 package (v. 1.1–35.1)474,490 in R. We then compared the mean of residuals to the values of our metaweb to determine whether our residual values were outliers (values outside two standard deviations of the mean). For both metrics, our metaweb remained within two standard deviations (Fig. 4). The European tetrapod metaweb was the only outlier for both metrics. Thus, for its size, this metaweb contained relatively more interactions between the species, and a relatively larger variation in the number of links per species. This result is understandable, as this metaweb has a strong bias towards well-studied organisms (tetrapods)491, in a geographic region where biodiversity had historically been relatively better-studied (Europe) than other parts of the globe492. Although data gaps remain (see Technical Validation: Data completeness), we argue that our trophic data coverage for species is on par with other existing empirical metawebs. To our knowledge, trophiCH represents the largest empirically based metaweb in existence, both in terms of species richness and trophic levels. In comparison, the next largest metaweb (see Supplementary Information Table S1) contains a fifth of the species richness and only includes plant-frugivore interactions.

Comparison of trophiCH to other metawebs. The scatterplots compare log species richness to the residual variation from mixed linear effects models predicting mean degree (left) and standard deviation of degree (right), treating the type of network as a random effect. The colours of the data points represent the type of ecosystem (aquatic: purple, marine: blue, terrestrial: green and terrestrial, aquatic, semiaquatic: orange). The shapes represent the type of network (circle: bitrophic, triangle: multi-trophic). The dark beige rectangles represent the first(±σ) and the light beige rectangles represent the second (±2σ) standard deviations from the mean(x̄).

Usage Notes

This work compiles a large empirically based dataset of species interactions along with species-species interactions inferred based on empirical interactions known at lower taxonomic resolution. The temporal span of our sources (1862–2023) reflects the accumulation of ecological knowledge over time. Indeed, over 95% of the interactions documented within our empirical metaweb were published after the year 2000. It should be noted, however, that the publication year does not necessarily correspond to the date of observation, which is often not reported in books. This additionally introduces a methodological bias: older sources often document only a few observed interactions per taxon, while modern approaches—particularly metabarcoding and database aggregations—can yield hundreds or thousands of interactions in a single dataset. As our metaweb documents potential interactions filtered by present-day species occurrence in Switzerland, the original publication year does not imply that the interaction still occurs today, but rather that it is ecologically plausible. We emphasise again that this is a metaweb, including many interactions that may not be realised at any singular point in space and time. Users should be aware of these methodological and temporal heterogeneities when interpreting the data.

Additionally, when existing metawebs were incorporated into our metaweb, some of the data had already been inferred based on empirical knowledge. For example, the bird-plant interactions in the Swiss bird-lepidoptera-plant metaweb20 were inferred based on expert knowledge of broad diet preferences and habitat-associations. The metaweb serves as an archive that ecologists can use, for example, to create their own local networks – using local occurrence data or simulations. The complete transparency of our metaweb with regard to the derivation of the individual interactions and their data sources enables customization to the individual needs and requirements of the users. Future studies should check the quality of each data point with regards to their research aims before using the dataset in its complete form. Moreover, we note that our metaweb approach does not provide quantitative information about the importance or abundance of each interaction (i.e. weighted interactions). Hence, the derived food webs provide qualitative and not quantitative insights on ecological networks. Finally, a metaweb approach is, by definition, dependent on the assumption that species that interact in the metaweb will always interact at the local scale if they are found to co-occur16,23. This collapses local scale variation due to abiotic and biotic variation, and only accounts for variation in interactions due to shifting species distributions. Future work should aim to incorporate spatial variation in both the occurrence and strength of interactions, which will require new data and methodological advances.

For the rapid visualisation and exploration of the dataset, we additionally host an R Shiny application, available at: https://webapps.wsl.ch/trophiCH.

Code availability

We provide five scripts, accompanying functions, and the raw data required to run these scripts to reproduce the taxonomic expansion and validation of the datasets469. In the first script (01_inferring_interactions.R), we infer interactions using genus and family level interactions and for basal feeding guilds (see Methods: Taxonomic expansion). In the second script (02_inferring_interactions_special_cases.R), we infer further interactions for a few special cases with detailed explanations. In the third script (03_metaweb_comparisons.Rmd), we provide the statistical comparisons between our metaweb and other empirical metawebs as an R Markdown document (see Technical Validation: Comparison to other empirical metawebs), reproducing Fig. 4. We additionally provide a Python Jupyter Notebook document, outlining the error validation of the data extraction process (04_error_validation.ipynb and an accompanying.html file). Finally, we provide a script to reproduce Fig. 1 (05_metaweb_summary_figure_1.R).

References

Chen, I.-C., Hill, J. K., Ohlemüller, R., Roy, D. B. & Thomas, C. D. Rapid Range Shifts of Species Associated with High Levels of Climate Warming. Science 333, 1024–1026 (2011).

Stephens, P. A. et al. Consistent response of bird populations to climate change on two continents. Science 352, 84–87 (2016).

Montoya, J. M., Pimm, S. L. & Solé, R. V. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature 442, 259–264 (2006).

Bascompte, J. Disentangling the web of life. Science 325, 416–419 (2009).

Thompson, R. M. et al. Food webs: reconciling the structure and function of biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 27, 689–697 (2012).

Araújo, M. B. & Luoto, M. The importance of biotic interactions for modelling species distributions under climate change. Global Ecology and Biogeography 16, 743–753 (2007).

Harvey, E., Gounand, I., Ward, C. L. & Altermatt, F. Bridging ecology and conservation: from ecological networks to ecosystem function. Journal of Applied Ecology 54, 371–379 (2016).

Oehri, J., Schmid, B., Schaepman-Strub, G. & Niklaus, P. A. Terrestrial land-cover type richness is positively linked to landscape-level functioning. Nature Communications 11, 154 (2020).

Mayor, S. et al. Diversity–functioning relationships across hierarchies of biological organization. Oikos 2024, e10225 (2024).

Buckley, L. B. et al. Phylogeny, niche conservatism and the latitudinal diversity gradient in mammals. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277, 2131–2138 (2010).

Davies, T. J. & Buckley, L. B. Phylogenetic diversity as a window into the evolutionary and biogeographic histories of present-day richness gradients for mammals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366, 2414–2425 (2011).

Benton, M. J. The origins of modern biodiversity on land. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365, 3667–3679 (2010).

Theodoridis, S. et al. Evolutionary history and past climate change shape the distribution of genetic diversity in terrestrial mammals. Nat Commun 11, 2557 (2020).

Jetz, W., Thomas, G. H., Joy, J. B., Hartmann, K. & Mooers, A. O. The global diversity of birds in space and time. Nature 491, 444–448 (2012).

Thompson, J. N. The Evolution of Species Interactions. Science 284, 2116–2118 (1999).

Pellissier, L. et al. Comparing species interaction networks along environmental gradients. Biological Reviews 93, 785–800 (2018).

Paquette, A. & Hargreaves, A. L. Biotic interactions are more often important at species’ warm versus cool range edges. Ecology Letters 24 (2021).

Pearse, I. S. & Altermatt, F. Extinction cascades partially estimate herbivore losses in a complete Lepidoptera-plant food web. Ecology 94, 1785–1794 (2013).

Visser, M. E. & Both, C. Shifts in phenology due to global climate change: The need for a yardstick. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272, 2561–2569 (2005).

Ho, H.-C. et al. Blue and green food webs respond differently to elevation and land use. Nat Commun 13, 6415 (2022).

Blackman, R. C., Ho, H. C., Walser, J. C. & Altermatt, F. Spatio-temporal patterns of multi-trophic biodiversity and food-web characteristics uncovered across a river catchment using environmental DNA. Communications Biology 2022 5:1 5, 1–11 (2022).

CaraDonna, P. J. et al. Seeing through the static: the temporal dimension of plant–animal mutualistic interactions. Ecology Letters 24, 149–161 (2021).

Dunne, J. A. The network structure of food webs. in Ecological Networks: Linking Structure to Dynamics in Food Webs (eds. Pascual, M. & Dunne, J.) 25–76 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006).

Maiorano, L., Montemaggiori, A., Ficetola, G. F., O’Connor, L. & Thuiller, W. TETRA-EU 1.0: A species-level trophic metaweb of European tetrapods. Global Ecology and Biogeography 29, 1452–1457 (2020).

Neff, F. et al. Changes in plant-herbivore network structure and robustness along land-use intensity gradients in grasslands and forests. Science Advances 7, 18 (2021).

Adhurya, S., Agasti, N. & Park, Y. Metaweb and its applications in understanding ecological interactions. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.32942/X2SW3V (2023).

Pellissier, L. et al. Combining food web and species distribution models for improved community projections. Ecology and Evolution 3, 4572–4583 (2013).

Albouy, C. et al. The marine fish food web is globally connected. Nature Ecology and Evolution 3, 1153–1161 (2019).

Williams, R. J. & Martinez, N. D. Simple rules yield complex food webs. Nature 404, 180–183 (2000).

Williams, R. J. & Martinez, N. D. Success and Its Limits among Structural Models of Complex Food Webs. Journal of Animal Ecology 77, 512–519 (2008).

Grünig, M., Mazzi, D., Calanca, P., Karger, D. N. & Pellissier, L. Crop and forest pest metawebs shift towards increased linkage and suitability overlap under climate change. Communications Biology 3 (2020).

Planque, B. et al. Who eats whom in the Barents Sea: a food web topology from plankton to whales. Ecology 95, 1430–1430 (2014).

Olivier, P. et al. Exploring the temporal variability of a food web using long-term biomonitoring data. Ecography 42, 2107–2121 (2019).

Dáttilo, W. & Vasconcelos, H. L. Macroecological patterns and correlates of ant–tree interaction networks in Neotropical savannas. Global Ecology and Biogeography 28, 1283–1294 (2019).

Adhurya, S., Lee, D.-Y. & Park, Y.-S. KF-metaweb: A trophic metaweb of freshwater ecosystems of South Korea. Global Ecology and Biogeography 33, e13845 (2024).

Braga, J. et al. Spatial analyses of multi-trophic terrestrial vertebrate assemblages in Europe. Global Ecology and Biogeography 28, 1636–1648 (2019).

Pacini, E., Viegi, L. & Franchi, G. G. Types, evolution and significance of plant – animal interactions. Rendiconti Lincei 19, 75–101 (2008).

Pitteloud, C. et al. The structure of plant–herbivore interaction networks varies along elevational gradients in the European Alps. Journal of Biogeography 48, 465–476 (2021).

BAFU. Artenvielfalt in der Schweiz. Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU https://www.bafu.admin.ch/bafu/de/home/themen/biodiversitaet/zustand-der-biodiversitaet-in-der-schweiz/zustand-der-artenvielfalt-in-der-schweiz.html (2023).

InfoSpecies. https://www.infospecies.ch/de/.

Morales-Castilla, I., Matias, M. G., Gravel, D. & Araújo, M. B. Inferring biotic interactions from proxies. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 30, 347–356 (2015).

Loeuille, N. Consequences of adaptive foraging in diverse communities. Functional Ecology 24, 18–27 (2010).

Bartley, T. J. et al. Food web rewiring in a changing world. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 345–354 (2019).

Ho, H.-C., Tylianakis, J. M., Zheng, J. X. & Pawar, S. Predation risk influences food-web structure by constraining species diet choice. Ecology Letters 22, 1734–1745 (2019).

Clegg, T., Ali, M. & Beckerman, A. P. The impact of intraspecific variation on food web structure. Ecology 99, 2712–2720 (2018).

Bolnick, D. I. et al. Why intraspecific trait variation matters in community ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 26, 183–192 (2011).

Kortsch, S. et al. Food-web structure varies along environmental gradients in a high-latitude marine ecosystem. Ecography 42, 295–308 (2019).

O’Connor, M. I., Piehler, M. F., Leech, D. M., Anton, A. & Bruno, J. F. Warming and Resource Availability Shift Food Web Structure and Metabolism. PLOS Biology 7, e1000178 (2009).

Saravia, L. A., Marina, T. I., Kristensen, N. P., De Troch, M. & Momo, F. R. Ecological network assembly: How the regional metaweb influences local food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology 91, 630–642 (2022).

Dunne, J. A., Williams, R. J. & Martinez, N. D. Food-web structure and network theory: The role of connectance and size. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99, 12917–12922 (2002).

Olesen, J. M., Bascompte, J., Dupont, Y. L. & Jordano, P. The modularity of pollination networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 19891–19896 (2007).

Bascompte, J., Jordano, P., Melián, C. J. & Olesen, J. M. The nested assembly of plant-animal mutualistic networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 9383–9387 (2003).

Reji Chacko, M., Albouy, C., Altermatt, F. et al. Species loss in key habitats accelerates regional food web disruption. Commun Biol 8, 988 https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08396-y (2025).

Perrelet, K., Cook, L., Reji Chacko, M., Altermatt, F. & Moretti, M. Urbanization drives the decoupling, simplification, and homogenization of aquatic and terrestrial food webs. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.22541/au.174559004.40925248/v1 (2025).

Reji Chacko, M. et al. Elevation and land use gradients drive food web structure and trophic connectivity. in Unveiling spatial patterns of multi-trophic biodiversity using the metaweb approach. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000710558 (ETH Zurich, Zurich, 2024).

Külling, N. et al. SWECO25: a cross-thematic raster database for ecological research in Switzerland. Sci Data 11, 21 (2024).

Galiana, N. et al. The spatial scaling of food web structure across European biogeographical regions. Ecography 44, 653–664 (2021).

O’Connor, L. M. J. et al. Unveiling the food webs of tetrapods across Europe through the prism of the Eltonian niche. Journal of Biogeography 47, 181–192 (2020).

Poisot, T., Guéveneux‐Julien, C., Fortin, M., Gravel, D. & Legendre, P. Hosts, parasites and their interactions respond to different climatic variables. Global Ecol Biogeogr 26, 942–951 (2017).

Ho, H.-C. & Altermatt, F. Associating the structure of Lepidoptera-plant interaction networks across clades and life stages to environmental gradients. Journal of Biogeography 51, 725–738 (2024).

CSCF. info fauna | Data Server. info fauna Nationales Daten- und Informationszentrum der Schweizer Fauna https://lepus.infofauna.ch/tab/ (2017).

Song, C., Altermatt, F., Pearse, I. & Saavedra, S. Structural changes within trophic levels are constrained by within-family assembly rules at lower trophic levels. Ecology Letters 21, 1221–1228 (2018).

Strydom, T. et al. Food web reconstruction through phylogenetic transfer of low-rank network representation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 13, 2838–2849 (2022).

Cagua, E. F., Wootton, K. L. & Stouffer, D. B. Keystoneness, centrality, and the structural controllability of ecological networks. Journal of Ecology 107, 1779–1790 (2019).

Blick, T., Muster, C. & Ducháč, V. Checkliste Der Pseudoskorpione Mitteleuropas Checklist of the Pseudoscorpions of Central Europe (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones). Version 1. Oktober 2004. https://arages.de/fileadmin/Pdf/checklist2004_pseudoscorpiones.pdf (2004).

Braunwalder, M. E. Scorpiones (Arachnida). (Centre suisse de Cartographie de la Faune, Schweizerische Entomologische Gesellschaft, 2005).

Pedroli-Christen, A., Geiger, W. & Christen, V. Faunistique des mille-pattes de Suisse (Diplopoda) = Faunistik der Tausendfüssler der Schweiz (Diplopoda). (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 1993).

de Jong, Y. et al. Fauna Europaea – all European animal species on the web. Biodiversity Data Journal 2, e4034 (2014).

Reibnitz, J., Graf, R. & Coray, A. Verzeichnis der Ciidae (Coleoptera) der Schweiz mit Angaben zur Nomenklatur und Ökologie = Checklist of the Ciidae (Coleoptera) of Switzerland, with comments on nomenclature and ecology. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen entomologischen Gesellschaft 86, 63 (2013).

Breitenmoser, S. & Chittaro, Y. & Sanchez, A. Liste commentée des Oedemeridae (Coleoptera) de Suisse = Commented checklist of Swiss Oedemeridae (Coleoptera). Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen entomologischen Gesellschaft 89, 73 (2016).

Chittaro, Y. & Sanchez, A. Liste commentée des Tenebrionoidea (Coleoptera) de Suisse: Partie 1 = Commented checklist of Swiss Tenebrionoidea (Coleoptera): Part 1. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen entomologischen Gesellschaft 89, 183 (2016).

Cosandey, V., Sanchez, A. & Chittaro, Y. Liste commentée des Scarabaeoidea (Coleoptera) de Suisse. Alpine Entomology 1, 57–90 (2017).

Gurcel, K., Chittaro, Y. & Sanchez, A. Contribution à la connaissance des lucioles et lampyres de Suisse et observation de Luciola lusitanica Charpentier, 1825 à Genève (Coleoptera, Lampyridae). 13/2020, 81–96 (2020).

Chittaro, Y. & Sanchez, A. Ampedus tristis (Linnaeus, 1758): une espèce nouvelle pour la faune de Suisse (Coleoptera, Elateridae). Entomo Helvetica 9/2016, 115–122 (2016).

Chittaro, Y. & Blanc, M. Liste commentée des Cerophytidae, Elateridae, Eucnemidae et Throscidae (Coleoptera) de Suisse = Annotated checklist of the Cerophytidae, Elateridae, Eucnemidae and Throscidae (Coleoptera) of Switzerland. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen entomologischen Gesellschaft 85, 91 (2012).

Chittaro, Y., Sanchez, A. & Geiser, M. An updated checklist of the Cantharidae and Lycidae of Switzerland (Coleoptera, Elateroidea). Alpine Entomology 5, 77–94 (2021).

Sanchez, A., Chittaro, Y., Germann, C. & Knížek, M. Annotated checklist of Scolytinae and Platypodinae (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) of Switzerland. Alpine Entomology 4, 81–97 (2020).

Germann, C. Erster Nachtrag zur Checkliste der Rüsselkäfer der Schweiz (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) = First additions to the Checklist of the Swiss weevil fauna (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea). Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen entomologischen Gesellschaft 86, 151 (2013).

Germann, C. Supplement zur Checkliste der Rüsselkäfer der Schweiz (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) = Supplement to the checklist of the weevils (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) of Switzerland. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen entomologischen Gesellschaft 84, 155 (2011).

Germann, C. Die Rüsselkäfer (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) der Schweiz mit Verbreitungsangaben nach biogeografischen Regionen. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen entomologischen Gesellschaft 83, 41 (2010).

Sanchez, A. & Chittaro, Y. Annotated checklist of the Coccinellidae (Coleoptera, Coccinelloidea) of Switzerland. Alpine Entomology 6, 111–127 (2022).

Chittaro, Y. & Sanchez, A. Liste commentée des Cleroidea (Coleoptera) de Suisse. Alpine Entomology 3, 141–167 (2019).

Carron, G. Checklist des coléoptères aquatiques de Suisse: deuxième partie: Gyrinidae, Haliplidae, Paelobiidae, Sphaeriusidae. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft 81, 53–60 (2008).

Luka, H., Marggi, W., Huber, C., Gonseth, Y. & Nagel, P. Coleoptera, Carabidae: ecology - atlas. Coleoptera, Carabidae ecology - atlas (Centre Suisse de Cartographie de la Faune, Neuchâtel, 2009).

Carron, G. Kommentierte Checkliste der Dytiscidae und Noteridae (Coleoptera) der Schweiz. Kommentierte Checkliste der Dytiscidae und Noteridae (Coleoptera) der Schweiz 55, 93–114 (2005).

Monnerat, C., Chittaro, Y. & Sanchez, A. Liste commentée des Lucanidae, Cetoniidae, Buprestidae et Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) de Suisse = Annotated checklist of the Lucanidae, Cetoniidae, Buprestidae and Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) of Switzerland. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft 88, 173 (2015).

Chittaro, Y. & Sanchez, A. Liste commentée des Bostrichoidea et Derodontoidea de Suisse (Coleoptera: Bostrichiformia, Derodontiformia). Alpine Entomology 3, 175–205 (2019).

GBIF.org. Occurrence Download (12 April 2022). The Global Biodiversity Information Facility https://doi.org/10.15468/DL.TD2FUQ (2022).

Bächli, G., Merz, B. & Haenni, J.-P. Dritter Nachtrag zur Checkliste der Diptera der Schweiz. Entomo Helvetica 7, 119–140 (2014).

Bächli, G., Merz, B., Geiger, W., Gonseth, Y. & Haenni, J.-P. Diptera: Checklist. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 1998).

GBIF.org. Occurrence Download (15 March 2022): Swiss National Databank of Mayflies, Stoneflies and Caddiesflies. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility https://doi.org/10.15468/DL.3W327M (2022).

Kozár, F., Guignard, E. & Bachmann, F. The scale insect and whitefly species of Switzerland (Homoptera: Coccoidea and Aleyrodoidea). Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft 67, 151–161 (1994).

Aukema, B. Catalogue of Palaearctic Heteroptera: Introduction (2013).

Lampel, G. & Meier, W. Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha - Aphidina. Hemiptera Sternorrhyncha - Aphidina (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2003).

Mühlethaler, R., Trivellone, V., Van Klink, R., Niedringhaus, R. & Nickel, H. Kritische Artenliste der Zikaden der Schweiz (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha). Cicadina 16, 49–87 (2016).

Amiet, F., Herrmann, M., Müller, A. & Neumeyer, R. Andrena, Melitturga, Panurginus, Panurgus. (Centre Suisse de Cartographie de la Faune, Neuchâtel, 2010).

Amiet, F., Herrmann, M., Müller, A. & Neumeyer, R. Ammobates, Ammobatoides, Anthophora, Biastes, Ceratina, Dasypoda, Epeoloides, Epeolus, Eucera, Macropis, Melecta, Melitta, Nomada, Pasites, Tetralonia, Thyreus, Xylocopa. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2007).

Amiet, F., Herrmann, M., Müller, A. & Neumeyer, R. Anthidium, Chelostoma, Coelioxys, Dioxys, Heriades, Lithurgus, Megachile, Osmia, Stelis. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2004).

Amiet, F., Herrmann, M., Müller, A. & Neumeyer, R. Halictus, Lasioglossum. (Schweizerische Entomologische Gesellschaft, Neuchâtel, 2001).

Amiet, F. Hymenoptera Apidae. 1. Teil, Allgemeiner Teil, Gattungsschlüssel, die Gattungen Apis, Bombus und Psithyrus. Insecta Helvetica. Fauna 12 (1996).

Amiet, F., Müller, A. & Neumeyer, R. Colletes, Dufourea, Hylaeus, Nomia, Nomioides, Rhophitoides, Rophites, Sphecodes, Systropha. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2014).

Amiet, F., Burckhardt, D. & Gonseth, Y. Mutillidae, Sapygidae, Scoliidae, Tiphiidae: (Hymenoptera, Vespoidea). Mutillidae, Sapygidae, Scoliidae, Tiphiidae (Hymenoptera, Vespoidea) (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2008).

Linsenmaier, W. Die Goldwespen Der Schweiz. (Natur-Museum, Lucerne, 1997).

Starý, P. Aphid Parasitoids of the Czech Republic (Hymenoptera: Braconidae, Aphidiinae). (Academia, Praha, 2006).

Noyes, J. S. Universal Chalcidoidea Database (2024).

Bryner, R. Die Schmetterlinge (Lepidoptera) der Schweiz: eine kommentierte, systematisch-faunistische Liste. (Centre Suisse de Cartographie de la Faune, Neuchâtel, 2010).

Merz, B. Liste annotée des insectes (Insecta) du canton de Genève. (MHN, Genève, 2012).

Maibach, A., Gonseth, Y., Wildermuth, H. & Robert, P.-A. Odonata: die Libellen der Schweiz. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2005).

Baur, B., Nadig, A., Baur, H., Roesti, C. & Roesti, D. Die Heuschrecken der Schweiz. (Haupt Verlag, Bern, 2006).

BAFU. Rote Listen Eintagsfliegen, Steinfliegen, Köcherfliegen: gefährdete Arten der Schweiz, Stand 2010. (Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU, Bern, 2012).

Altermatt, F. et al. Amphipoda (Flohkrebse) Der Schweiz: Checkliste, Bestimmung Und Atlas. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2019).

Fišer, C., Konec, M., Alther, R., Švara, V. & Altermatt, F. Taxonomic, phylogenetic and ecological diversity of Niphargus (Amphipoda: Crustacea) in the Hölloch cave system (Switzerland). Systematics and Biodiversity 15, 218–237 (2017).

Fišer, C. et al. Translating Niphargus barcodes from Switzerland into taxonomy with a description of two new species (Amphipoda, Niphargidae). ZK 760, 113–141 (2018).

Altermatt, F. et al. Diversity and Distribution of Freshwater Amphipod Species in Switzerland (Crustacea: Amphipoda). PLoS ONE 9, e110328 (2014).

Alther, R., Bongni, N., Borko, Š., Fišer, C. & Altermatt, F. Citizen science approach reveals groundwater fauna in Switzerland and a new species of Niphargus (Amphipoda, Niphargidae). SB 39, 1–31 (2021).

Stucki, P. & Zaugg, B. Decapoda: Atlas. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la Faune, Neuchâtel, 2005).

Burckhardt, D., Baer, T., Gonseth, Y., Thew, N. & Turner, H. Atlas Der Mollusken Der Schweiz Und Liechtensteins. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 1998).

Stucki, P., Pedroli, J.-C. & Zaugg, B. Pisces: Atlas. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2003).

Knaus, P., Sattler, T., Schmid, H., Strebel, N. & Volet, B. Birds of Switzerland. https://www.vogelwarte.ch/en/birds/birds-of-switzerland/ (2023).

Graf, R. F., Fischer, C. & Niehaus, M. Atlas Der Säugetiere: Schweiz Und Liechtenstein. (Haupt Verlag, Bern, 2021).

InfoFlora. Checklist 2017. https://www.infoflora.ch/en/flora/taxonomy.html#checklist (2017).

GBIF.org. Occurrence Download (07 May 2024). The Global Biodiversity Information Facility https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.t7rrhw (2024).

Google. Google Scholar. Google Scholar https://scholar.google.com/.

Google. Dataset Search. Google Dataset Search https://datasetsearch.research.google.com/.

SLSP AG. swisscovery. https://swisscovery.slsp.ch.

Hölzel, H., Weißmair, W. & Speidel, W. Süßwasserfauna von Mitteleuropa. Bd. 15, 16, 17: Insecta: Megaloptera, Neuroptera, Lepidoptera: (Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 2002).

Kaltenbach, A., Helmcke, J. G., Starck, D., Wermuth, H. & Kükenthal, W. Mecoptera (Schnabelhafte, Schnabelfliegen). (De Gruyter, Berlin and New York, 1978).

Rozkosny, R. & Kniepert, F. W. Süßwasserfauna von Mitteleuropa, Bd. 21/18+19: Insecta: Diptera: Stratiomyidae Und Tabanidae. (Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 2000).

Haupt, J. & Haupt, H. Fliegen Und Mücken: Beobachtung, Lebensweise. (Naturbuch-Verlag, 1998).

Graf, W., Murphy, J., Dahl, J., Zamora-Muñoz, C. & López-Rodríguez, M. J. Vol. 1. Trichoptera. Distribution and Ecological Preferences of European Freshwater Organisms. Pensoft Publishers, Sofia, Moscow (2008).

Ulmer, G. Trichoptera. (G. Fischer, 1909).

Smit, F. G. A. M. Siphonaptera. Insecta Helvetica. Catalogus 1 (1966).

White, M. Insecta 2. Blattodea, Mantodea, Isoptera, Grylloblattodea, Phasmatodea, Dermaptera and Embioptera. (Schweizerbart Science Publishers, Stuttgart, Germany, 1976).

Holman, J. Host Plant Catalog of Aphids: Palaearctic Region. (Springer Netherlands, 2008).

Röösli, T., Steffen, M., Berner, D., Schweiz, S. V. S. & Schweizer Vogelschutz, V. für V. N. Heuschrecken Der Schweiz. (SVS, 2004).

Weidner, H., Helmcke, J. G., Starck, D., Wermuth, H. & Kükenthal, W. Copeognatha (Psocodea). (De Gruyter, Berlin and New York, 1972).

Székessy, V. Strepsiptera. (Springer, Wien, 1970).

Rosenberg, J. & Voigtländer, K. Die Hundertfüsser: Chilopoda. (Westarp Wissenschaften, Hohenwarsleben, 2009).

Jean-Richard, P., Keller, H. & Naturschutz, S. B. für. Krebse in der Schweiz: erleben, beobachten, bestimmen, hegen. (Schweiz. Bund für Naturschutz, Basel, 1994).

Steinmann, P. & Krämer, W. Die Fische der Schweiz. (Sauerländer, Aarau, 1936).

Willner, W. Taschenlexikon der Käfer Mitteleuropas: die wichtigsten Arten im Porträt. (Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim, 2013).

Boschi, C. Die Schneckenfauna der Schweiz: ein umfassendes Bild- und Bestimmungsbuch. (Haupt Verl, Bern, 2011).

Studemann, D., Landolt, P. & Sartori, M. Ephemeroptera. vol. 9 (Schweizerische entomologische Gesellschaft = Société entomologique suisse, 1992).

Lubini, V. et al. Die Steinfliegen der Schweiz: Bestimmung und Verbreitung = Les plécoptères de Suisse: identification et distribution. (Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2012).

Neumeyer, R. Vespidae. (Info fauna - Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune, Neuchâtel, 2019).

Daly, H. V. et al. Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1998).

Brunel, E. Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera (with Special Reference to Flies of Economic Importance). vol. 3: Higher Brachycera (Science Herald, Budapest, 1998).

Borror, D. J., Triplehorn, C. A. & Johnson, N. F. An Introduction to the Study of Insects. (Saunders College, Philadelphia [etc, 1989).

Loew, H. Monographs Of The Diptera Of North America. (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1862).

Vaillant, H. F. J. O. T. F. Die Fliegen Der Palaearktischen Region. Familie 9 (a-d): Psychodidae: Bruchomyiinae, Trichomyiinae, Phlebotominae, Psychodinae. (Schweizerbart Science Publishers, Stuttgart, Germany, 1958).

Gordh, G. & Headrick, D. A Dictionary of Entomology. (CABI Pub., 2001).

Lukešová, A. & Frouz, J. Soil and Freshwater Micro-Algae as a Food Source for Invertebrates in Extreme Environments. in Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Environments (ed. Seckbach, J.) 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6112-7_14 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2007).

Arnett, R. H. American Insects: A Handbook of the Insects of America North of Mexico. (Sandhill Crane Press, Gainesville, Fla, 1993).

Hull, F. M. Robber Flies of the World: The Genera of the Family Asilidae. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 224, 1–907 (1962).

McAlpine, J. F. et al. Manual of Nearctic Diptera. Volume 1. (Agriculture Canada, Ottawa, 1981).

Smith, K. G. V. An Introduction to the Immature Stages of British Flies: Diptera Larvae, with Notes on Eggs, Puparia and Pupae., (1989).

Ingrisch, S. & Köhler, G. Die Heuschrecken Mitteleuropas. (Westarp Wissenschaften, Magdeburg, 1998).

Maas, S., Detzel, P. & Staudt, A. Gefährdungsanalyse der Heuschrecken Deutschlands: Verbreitungsatlas, Gefährdungseinstufung und Schutzkonzepte. (Bundesamt für Naturschutz, Bonn-Bad Godesberg, 2002).

Detzel, P., Baden-Württemberg, A. & Baden-Württemberg, L. für U. Die Heuschrecken Baden-Württembergs. (Ulmer, Stuttgart (Hohenheim), 1998).

Kottelat, M. & Freyhof, J. Handbook of European Freshwater Fishes. (Kottelat, Cornol, 2007).

White, D. S. Coleoptera (Beetles) in Aquatic Ecosystems. in Encyclopedia of Inland Waters 144–156 (Elsevier, 2009).

Arnett, R. H. & Thomas, M. C. (Michael C. Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga: Staphyliniformia. Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga: Staphyliniformia (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla, 2001).

Aspöck, U. Megaloptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 1995).

Aspöck, U., Weißmair, W. & Waringer, J. Neuroptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 1995).

Bauernfeind, E., Weichselbaumer, P., Leitner, P. & Moog, O. Ephemeroptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Bauernfeind, E., Weichselbaumer, P., Leitner, P. & Moog, O. Ephemeroptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 1995).

Brojer, M., Jäch, M. A., Kodada, J. & Moog, O. Coleoptera: Water beetles. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2017).

Buffagni, A., Cazzola, M., López-Rodríguez, M. J., Alba-Tercedor, J. & Armanini, D. G. Schmidt-Kloiber, A. & Hering, D. (Eds.): Distribution and Ecological Preferences of European Freshwater Organisms. Ephemeroptera. vol. 3 (2009).

Zwick, P. et al. Diptera (except Chironomidae). in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Chovanec, A., Holzinger, W. E., Janecek, B. F. U. & Moog, O. Odonata. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2017).

Gaviria, S. et al. Crustacea. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Graf, W., Murphy, J., Dahl, J., Zamora-Munoz, C. & Lopez-Rodriguez, M. J. Distribution and Ecological Preferences of European Freshwater Organisms. Volume 1. Trichoptera. vol. 1 (Pensoft Publishing, Sofia-Moscow, 2008).

Graf, W., Grasser, U. & Waringer, J. Trichoptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 1995).

Graf, W., Grasser, U. & Waringer, J. Trichoptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Graf, W., Grasser, U. & Weinzierl, A. Plecoptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Graf, W., Grasser, U. & Weinzierl, A. Plecoptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 1995).

Huemer, P. & Tarmann, G. Lepidoptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Brojer, M., Jäch, M. A., Kodada, J. & Moog, O. Coleoptera: Water beetles. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Janecek, B. F. U. et al. Diptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2017).

Bauernfeind, E., Weichselbaumer, P., Leitner, P. & Moog, O. Ephemeroptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2017).

Pöckl, M., Borza, P., Nesemann, N. & Moog, O. Crustacea: Amphipoda, Isopoda, Decapoda. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2017).

Reischütz, A., Reischütz, P. L., Nesemann, N. & Moog, O. Mollusca. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Reischütz, A., Reischütz, P. L., Nesemann, N. & Moog, O. Gastropoda. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Schmedtje, U. & Colling, M. Ökologische Typisierung Der Aquatischen Makrofauna. (Bayerisches Landesamt für Wasserwirtschaft, 1996).

Zettel, H. & Rabitsch, W. Heteroptera. in Moog, O. & A. Hartmann (Eds.): Fauna Aquatica Austriaca (BMLFUW, Wien, 2002).

Minelli, A. Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda, Volume 2. (Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015).

James, M T. The Flies That Cause Myiasis in Man. vol. no. 631 (United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C, 1947).

Matheson, R. Medical Entomology. (Comstock Publishing Company Inc, Cornell University, 1932).

Remane, R. & Wachmann, E. Zikaden: kennenlernen - beobachten. Zikaden kennenlernen - beobachten (Naturbuch Verlag, Augsburg, 1993).

Blösch, M. Die Grabwespen Deutschlands: Sphecidae s.str., Crabronidae: Lebensweise, Verhalten, Verbreitung. (Goecke & Evers, Keltern, 2000).