Abstract

This study introduces FOWCUS, a novel dataset detailing the composition of about 280 food commodities, categorized into various groups including vegetables, fruits, nuts, eggs, livestock, seafood, cereals, sugar, vegetable oils, stimulants, pulses, and root vegetables. Unlike previous works focusing on the chemical composition of food products, this dataset extends to quantitatively capture the amounts of products and by-products that could potentially contribute to the generation of avoidable, potentially avoidable, and unavoidable food waste across the food supply chain. By providing a detailed breakdown of the different components of food products, this dataset aids in identifying potential revalorization opportunities for unavoidable food waste via, for instance, feedstocks for biochemical, biomaterial, and bioenergy applications. It also supports the quantification of food waste generation across the food supply chain, which is crucial for food waste studies and the monitoring of food waste reduction targets at the national and international levels. Indexed according to the FAOSTAT commodity typology, it serves as a valuable resource for researchers and policymakers in managing food waste and valorizing by-products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Globally, food waste represents a significant loss of resources in terms of energy, labor, and economic value. On an annual basis, about a third of global food production, or 1.3 Gt, is thrown away across the value chain from the farm to consumers’ plates1. Food waste is composed of both avoidable and unavoidable food waste. Avoidable food waste (AFW) is the discarded edible (parts of) food products, intended for human food consumption while unavoidable food waste (UFW) is the expected, non-consumable waste stream2. This dataset follows Yussof et al.’s approach2, offering a classification of “waste avoidability” for each food product’s components based on the concepts of avoidable, potentially avoidable, and unavoidable food waste.

Avoidable food waste has been found to create needless environmental impacts across the world. AFW generated at the consumer stage has been found to emit 396 Mt CO2 eq (100 GWP), use 61 billion m3 (Gm3) of water and 198 million hectares of land (for food crops, feed crops, and grazing)3. Unavoidable food waste, by definition, cannot be readily reduced, yet its management as waste remains critical. The vast majority of these two waste streams currently ends up in landfills and open dumps, generating millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases every year4, especially due to their methane emissions5.

The most effective way to decrease the impacts of avoidable food waste is to reduce its generation at its source. As a result, in recent years researchers have conducted studies focused on reducing waste through consumer behavior and supply chain efficiencies. Studies have shown that plate size reduction6, promoting healthy food7, informational campaigns8, online food-sharing platforms9, and new legislations10 can help reduce AFW. Assessing the effectiveness of these solutions remains a challenge due to the difficulty of accurately measuring food waste flows11 and understanding their precise composition between avoidable food waste flows that can be reduced, and unavoidable food waste flows that are expected to remain stable, by definition.

While unavoidable food waste may not be reduced, it is critical to manage it to limit its environmental impacts at the waste treatment stage and explore valorization pathways to extract as much value as possible from these bio-resources12. As such, many studies have been conducted over the last decade to explore the valorization of food by-products - be it, for vegetable and fruit waste13, seafood14, nuts, cereals15,16, or meat waste17. By and large, these studies have explored both the nutritional content of many food by-products, as well as the generation of value-added products from these waste streams in the form of bio-fuels, bio-materials, value-added components, and bio-based adsorbents. A large majority of experimental studies operates at a lab scale, and therefore do not quantify or only superficially the available feedstock should these valorization solutions be scaled up to achieve industrial scale. Additionally, countries also elaborate their own food composition database (such as Japan18, France19, England20, Turkey21, and Norway22 however, similarly to food waste valorization studies, the vast majority focuses on the chemical and nutritional contents of food items. Some of these national tables may provide some indication of the mass share of the products that are edible or usually consumed, but they do not provide further details on the specific mass share of their different edible and inedible parts.

In this study, we present FOWCUS23, the first comprehensive analysis of the avoidable, potentially avoidable, and unavoidable components of 276 food commodities, post-harvest. The data is meticulously indexed according to FAOSTAT food commodities typology (incl. FAO FishStat typology for seafood products), enhancing its applicability for national-level quantification of food waste feedstock. This dataset not only fills a critical gap in existing literature but also empowers the development of strategies for the bio-chemical, bio-material, and bio-energy sectors. Thanks to its detailed accounting of the avoidable, potentially avoidable, and unavoidable parts of food commodities, this dataset also provides novel support in food waste quantification studies by helping predict the expected amounts of these different waste streams generated at the regional or national levels.

This dataset supports studies that use the ‘waste floor’ approach24,25 that is, those that aim to quantify the minimum amounts of food waste that may be generated in a specific geography, as well as national and global food waste monitoring studies26. This dataset can also be used as a tool to estimate the potential waste feedstock for bio-energy, bio-chemicals, bio-compounds, bio-absorbents, and nutrients, such as phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium. Additionally, FOWCUS can be leveraged for more, stage-specific, supply chain analysis. For example, it can support the quantification of unavoidable food waste (e.g., by-products, residues) in specific food processing industries (e.g., slaughtering, milling, processed seafood) at an aggregated level, which could then be valorized by other industries, locally.

FOWCUS not only supports academic and industrial research but also assists policymakers in crafting targeted waste reduction strategies at a national level.

Methods

Literature review and data compilation

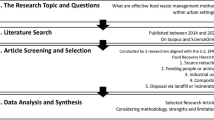

The list of commodities included in this study was retrieved from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) statistical database (FAOSTAT), detailing the global production of agricultural commodities in each country27. Additionally, the list of seafood commodities was retrieved from FAO’s FishStat database, which detailed the aquaculture production and wild capture of seafood commodities for each country28. This dataset is extensive and reports the landing or aquaculture production of more than 3500 seafood species. Due to the very large number, only the top 100 species by annual production volume were selected for this dataset. The top 100 species amounted to more than 80% of the global volume of seafood (2019 as base year) and therefore cover the majority of seafood items by volume. The remaining species were then grouped into different seafood categories. This process led to the inclusion of 276 commodities in this dataset, grouped into 12 food categories: vegetables, fruits, nuts, eggs, livestock, seafood, cereals, sugar, vegetable oils, stimulants, pulses, and root vegetables.

The methodology for developing the dataset began with an extensive literature review for each of the food commodities included in the final list. The goal was to collate exhaustive data on the mass of both edible and inedible components of each commodity, ensuring comprehensive coverage across all food categories. For this data collection process, the main key search terms used in combination with each of the names of FAO commodities were: ‘mass composition’, ‘mass share’, ‘mass balance’, ‘residues’, ‘valorization’, ‘yield’, ‘waste’, and ‘weight’. The main bibliographic sources were Google Scholar, Google Search Engine, and SCOPUS. More specific words were also utilized related to the specific morphologies of the commodities (e.g., endocarp, exocarp, etc.).

The data sources acquired and reviewed were peer-reviewed articles, guidelines, and reports from national agricultural ministries or departments (e.g., USDA, Australian Department of Agriculture, Italian Agricultural Ministry), international datasets from international organizations (e.g., FAO), and in some cases, industry reports. The data sources are compiled in the FOWCUS dataset for each food commodity and listed next to the relevant specific food commodities’ parts (see Data Records).

Setting mass balance boundaries

To accurately represent the mass composition of food products post-harvest, mass balance equations were employed for each commodity. These calculations were crucial in determining how the total mass of each harvested food commodity was distributed among its various components. This approach ensured that the summed mass percentages of all components, accounted for at the post-harvest stage, equaled 100%. This was essential to maintain the integrity and usability of the data, particularly for research applications in waste management and by-product valorization. The boundaries were set by first reviewing FAO commodity definitions and the Food Balance Sheet handbook prepared by the FAO Statistics Division detailing what is included in the production volumes. The description of the boundaries of the food products of each commodity group is compiled in Table 1.

Each food commodity has a wide diversity of parts. We aimed to harmonize these parts to the greatest extent possible without losing too much granularity in the specificities of each food commodity. Figure 1 illustrates a general sketch of the main food commodities parts included within FOWCUS for each of the 12 food groups. A majority of food commodities in each food group are composed of these parts, although some specific commodities within the same food group may still differ significantly due to their anatomy (e.g., olive and palm fruits in the Vegetable Oils group, artichoke in the Vegetables group). We highlighted which parts are not usually included in FAO production statistics (dashed boxes in Fig. 1).

Mass balance calculations

Once the boundaries and the inventory of parts composing each food commodity were set, the mass balance equations could be established. The mass balance equation was balanced based on the different data sources collected for each commodity, such that the total sum of the mass of each part equaled 100% of the mass of the food commodity (Eq. 1).

Data standardization and verification

Following the data collection and calculation phases, the resulting data were standardized to ensure consistency across all entries. This process involved 1) harmonizing to the greatest extent the parts' names; and 2) reviewing the mass composition of each food commodity within the same food group to ensure consistency in the boundaries set and in the definitions of the different parts (e.g., husk vs. hull). During this step, each part (e.g., hull, shell) was assessed against the FAOSTAT commodity definition to highlight whether or not it was accounted for in FAOSTAT production datasets (see Data records for description).

This distinction is critical for the utilization of this dataset to quantify the amounts of unavoidable food waste generated during the production of these commodities. Indeed, for tree nuts commodities, such as almonds, the hull is not included in FAO production statistics. In the case of almonds, this dataset describes the composition of almonds, such as the hull, the shell, the skin, and the kernel amounting to 100% of the volume of this commodity. In the almond example, to quantify the volume of these four parts using FAOSTAT production data for a given country, the production amount was adjusted to include the almonds’ hulls. The adjustment is described in Eq. 2.

Where \({Food\; commodity}\,{X}_{{Adjusted\; production\; volume}}\) is the adjusted production volume (tonnes) of food commodity X, \({Food\; commodity}\,{X}_{{FAO\; production\; volume}}\) is the volume (in tonnes) retrieved from FAOSTAT production datasets, and \(\sum {mass\; share\; part}\,{x}_{{not\; accounted\; in\; FAO}}\) is the sum of the mass share of the parts not included in the FAOSTAT production datasets.

Once the production volume is adjusted to account for parts (e.g. almonds’ hull) not included in FAO production, the mass of each part can be readily computed by using the mass share estimate from the FOWCUS dataset.

Where \({Part}\) \({x}_{{Commodity\; X}}\) is the mass (tonnes) of Part x of food commodity X and \({mass\; shar}{e}_{{part\; x}}\) is the percentage mass share of this part.

These calculation steps were performed for each food commodity to ensure that the dataset and its mass share estimates were in full alignment with the production data from FAOSTAT and to avoid any quantitative distortion in the underlying FAO production data. Using the example of almonds, these verification steps ensured that the quantities of almond shells, skins, and kernels, summed together, amounted to the FAO production data for Almonds, in shell, in addition to providing the mass of almond hulls produced.

Finally, the estimates gathered in this dataset were cross-referenced with data points from multiple sources where available and iteratively validated. This validation is further described in the Technical Validation section.

Unavoidable and avoidable food waste typology

Every part of each food commodity was classified as avoidable, potentially avoidable, and unavoidable. This classification has been used extensively by many researchers in the field of household food waste assessment29,30,31. This was done following the approach developed by Yusoff et al. (2024) where the main edible components of food products, considered safe to eat, are assigned as avoidable. Potentially Avoidable Food Waste (PAFW) is another category often added for ambiguous food components that depend on individuals’ preferences32 and is shaped by cultural norms33. Certain foods, like chicken feet, may be commonly eaten in some regions but are not widely consumed in others. However, in most instances, local experts can determine what is generally considered avoidable food waste and potentially avoidable food waste in their country. As such, food components, whose consumption depends on individual and cultural preferences are assigned potentially avoidable food waste, similar to Nicholes et al.34 and Okayama et al.31approaches. Finally, food components that have never been and will never be consumed by humans under normal circumstances were classified as unavoidable.

Data Records

This dataset is available on Figshare23 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27203688). The detailed mass compositions of food commodities are archived as a structured spreadsheet, and as such, are presented in a format that supports wide-ranging research activities from waste management to by-product valorization studies. FOWCUS is systematically arranged across several sheets within a single spreadsheet, one for each of the food group, enabling a straightforward navigation for researchers and practitioners.

-

General Information (1 sheet)

This section provides metadata on the dataset, including the scope and a concise description of the approach employed for FOWCUS data assembly as well as an index briefly describing the content of each sheet of the dataset.

-

Commodity Composition Data (12 sheets)

Each sheet presents a detailed tabulation of each food commodity with the mass percentages of all its components, as well as their waste qualification as avoidable, potentially avoidable, or unavoidable food waste. There is a sheet for each of the 12 food groups. All the relevant data sources and references are directly compiled alongside the mass share estimates.

-

Classification Notes (1 sheet)

This sheet details the classification and any grouping (e.g. seafood species) made during the data compilation.

To better illustrate the organization of the FOWCUS dataset, Table 2 provides an overview of the fields included in the Commodity Composition sheets, along with their descriptions.

Table 2 Food Commodity Mass Composition Data Fields.

Technical Validation

In order to validate our dataset, we collected data from additional sources to verify that the order of magnitude of the different parts composing a food commodity was similar to those reported in other sources.

The edibility percentage of food commodities was of special importance and was meticulously reviewed, since a key purpose of this dataset is to understand the share of the food that should (avoidable) or may (potentially avoidable) be consumed by humans, and the share that may be discarded as unavoidable food waste. Since our dataset describes in detail the different components of food commodities and whether they are usually consumed by humans, we compared the sum of the edible parts estimated in FOWCUS for each food item to the edibility or yield share estimates provided by various sources.

Specifically, we collected data from national (Japan19, United Kingdom20) and regional (West Africa35) food composition tables for fruits, vegetables, root vegetables, and nuts. For seafood, we collected additional data on fish processing from FAO’s own seafood food composition table36. For some food groups, the edibility percentage was not the most apt metric to validate our estimate, as it was not the way the literature assessed these food groups. For livestock, we collected additional data sources on dressing yields for key animals (i.e., cattle37,38, pig39, chicken40, horse41, sheep42) as it is one of the key metrics (closely linked to edibility) to determine yield from livestock slaughtering. For nuts43,44 and stimulants45, additional data on kernel/nut ratio were used, which is another ratio closely linked to the edibility percentage of nuts. For sugar crops (sugar cane46 and sugar beet47,48, the sugar content, the edible portion of the plant, was the metric used to validate the mass share estimates (Table 3). For cereals49,50,51, the kernel share relative to the seed grain was the key metric analyzed.

Where available, we listed the minimum and maximum edibility values (or another associated metric) found in the literature and compared the mid-point value of the range to the values present in our dataset (Eqs. 4 and 5).

This process was done iteratively, using a flag system to highlight any food commodity in the dataset with an edibility value above or below the ±20% range from the mid-point value. Whenever a food commodity in our dataset was flagged, the sources were reviewed and amended if necessary to refine the estimate in the dataset. This process was performed for all food commodities for which additional data could be collected.

Figure 2 describes the workflow followed to validate the data compiled in FOWCUS.

The validation process and the subsequent iterations in refining and adjusting the mass composition estimates led to the vast majority of the estimate points being within ±20% of the midpoint value. A few outliers remain, mostly due to the novel boundaries set for certain food items by this dataset to offer a more comprehensive view of the mass compositions of food items than most studies. Validation results are illustrated in Fig. 3. Figure 3 visualizes the validation results by showing the deviation of each food commodity’s estimate from the midpoint of the corresponding validation range. Commodities falling within ±20% of the midpoint value were considered validated, while those outside this range are flagged for further review.

We acknowledge that even with this validation process, inherent variations, and therefore uncertainties, remain due to the variety of species within a specific food item and the lack of repeated measurements for certain food commodities, which may make it difficult to fully validate the estimate of the mass share of their parts. It is the intention of this dataset to be updated as new data become available that can further validate or refine the data compiled.

Usage Notes

This dataset, accessible on FigShare, provides a comprehensive spreadsheet format suited for researchers and practitioners in food science, waste management, and bio-waste valorization. For optimal use, it is advised to familiarize oneself with its structure via the initial metadata sheet. Users can employ analysis tools like R, Python, or any spreadsheet-based software for data manipulation and are encouraged to integrate this dataset with other data sources for enriched insights.

To utilize the dataset at the national, regional, or global levels, the users may readily use FAOSTAT production datasets since our dataset is aligned with FAO food commodities typologies. To quantify animal parts, we advise the use of the Domestic Animal Diversity Information System (DAD-IS)52 to extract live-weight estimates of specific livestock raised within the national boundaries. This data should then be combined with the respective FAOSTAT estimate on the number of livestock slaughtered in this country to yield the total national live-weight production of livestock.

For food commodities belonging to the Cereals, Nuts, Legumes/Pulses, and Stimulants, this dataset includes parts (e.g., husk/hull/pod) that are not included in FAOSTAT production datasets. This is highlighted in the dataset (see Data Record section). To quantify the correct amounts of avoidable, potentially avoidable, and unavoidable food waste quantities for these commodities based on FAOSTAT production data, users must follow the quantification protocol described in the Methods section, which first adjusts the total production volumes from FAOSTAT to account for parts not included in its estimate (e.g., husk) and then apply the mass share percentage from this dataset.

While the data is robust and careful attention has been spent on validating the estimate whenever data allowed, we acknowledge inherent variability and measurement uncertainties in interpretations due to the variety of products covered in this dataset. As such, contributions to enhance dataset accuracy are welcome, adhering to our transparency and reproducibility standards to continuously improve FOWCUS and its accuracy.

Code availability

The code describing how to use this dataset is open-source and available at the GitHub repository: https://github.com/ACoudard/FOWCUS.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO, FAO: Rome, (2019).

Yusoff, N., Godsell, J., Woolley, E. Towards zero waste: A comprehensive framework for categorizing household food waste. Sustainable Production and Consumption. 48, ISSN 2352–5509, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2024.05.002 (2024).

Coudard, A., Sun, Z., Behrens, P. & Mogollón, J. M. The Global Environmental Benefits of Halving Avoidable Consumer Food Waste. Environmental Science & Technology. 58(31), 13707–13716, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c04140 (2024).

Kaza, S., Yao, L., Bhada-Tata, P. & Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. Urban Development Series; License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO World Bank: Washington, DC (2018).

Crippa, M. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2, 198–209, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9 (2021).

Wansink, B. & van Ittersum, K. Portion size me: plate-size induced consumption norms and win-win solutions for reducing food intake and waste. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 19(4), 320–332, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035053 (2013).

Schwartz, M. B., Henderson, K. E., Read, M., Danna, N. & Ickovics, J. R. New School Meal Regulations Increase Fruit Consumption and Do Not Increase Total Plate Waste. Childhood Obesity. 11(3), 242–247, https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2015.0019 (2015).

Reynolds, C. et al Review: Consumption-stage food waste reduction interventions – What works and how to design better interventions. Food Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.01.009 (2015).

Harvey, J., Smith, A., Goulding, J. & Branco Illodo, I. Food sharing, redistribution, and waste reduction via mobile applications: A social network analysis. Industrial Marketing Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.02.019 (2019).

Vaqué, L. G. F. and Italian Food Waste Legislation: An Example for other EU Member States to Follow? European Food and Feed Law Review 12(3), 224–233, https://www.jstor.org/stable/90010366 (2017).

Xue, L. et al. Missing food, missing data? A critical review of global food losses and food waste data. Environmental Science & Technology 51(12), 6618–6633, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b00401 (2017).

Nayak, A. & Bhushan, B. An overview of the recent trends on the waste valorization techniques for food wastes. Journal of Environmental Management. 233, 352–370, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.12.041 (2019).

Râpă, M., Darie-Niță, R. N. & Coman, G. Valorization of Fruit and Vegetable Waste into Sustainable and Value-Added Materials. Waste. 2(3), 258–278, https://doi.org/10.3390/waste2030015 (2024).

Zhan, Z., Feng, Y., Zhao, J., Qiao, M. & Jin, Q. Valorization of Seafood Waste for Food Packaging Development. Foods. 13(13), 2122, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13132122 (2024).

Plakantonaki, S., Roussis, I., Bilalis, D. & Priniotakis, G. Dietary Fiber from Plant-Based Food Wastes: A Comprehensive Approach to Cereal, Fruit, and Vegetable Waste Valorization. Processes. 11(5), 1580, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11051580 (2023).

Fărcaș, A. C. et al. Cereal Waste Valorization through Conventional and Current Extraction Techniques—An Up-to-Date Overview. Foods. 11(16), 2454, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11162454 (2022).

Boboua, S. Y. et al. Valorization of animal waste proteins for agricultural, food production, and medicinal applications. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1366333 (2024).

Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Standard tables of food composition in Japan (Seventh Revised Version). 2015. https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/science_technology/policy/title01/detail01/1374030.htm

Anses. Ciqual French food composition table. https://ciqual.anses.fr/ (2020).

Public Health England. McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset 2015. London. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/composition-of-foods-integrated-dataset-cofid

TürKomp. National Food Composition Database, version 1.0. www.turkomp.gov.tr (2015).

Norwegian Food Safety Authority. Norwegian Food Composition table. 2023. https://www.matvaretabellen.no/about-us/

Coudard, A., Szabo-Hemmings, T., Delval, M. H., Ravisandiran, S. M. & Mogollón, J. M. The FOod Commodity composition for Waste qUantification and valorization opportunitieS (FOWCUS) Dataset. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27203688 (2025).

De Laurentiis, V., Corrado, S. & Sala, S. Quantifying household waste of fresh fruit and vegetables in the EU. Waste Management. 77, 238–251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.04.001 (2018).

Caldeira, C., De Laurentiis, V., Corrado, S., van Holsteijn, F. & Sala, S. Quantification of food waste per product group along the food supply chain in the European Union: a mass flow analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 149, 479–488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.06.011 (2019).

United Nations Environment Programme, Food Waste Index Report 2024. Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste. Available: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/45230 (2024).

Food and Agriculture Organization. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; IGO, https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL. Dataset downloaded: “Crops and livestock products” (2024).

Food and Agriculture Organization. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture - Global Statistical Collections. 2024. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Division. Rome. https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/statistics/software/fishstatj. Dataset downloaded: “Global Production by production source 1950-2023”.

Cánovas Creus, A., Bernstad Saraiva, A. & Arruda, E. Structured evaluation of food loss and waste prevention and avoidable impacts: A simplified method. Waste Management & Research. 36(8), 698–707, https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242x18778779 (2018).

Herzberg, R., Schmidt, T. G. & Schneider, F. Characteristics and Determinants of Domestic Food Waste: A Representative Diary Study across Germany. Sustainability. 12(11), 4702, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114702 (2020).

Shaw, P. J., Smith, M. M. & Williams, I. D. On the Prevention of Avoidable Food Waste from Domestic Households. Recycling. 3(2), 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling3020024 (2018).

Okayama, T., Watanabe, K. & Yamakawa, H. Sorting Analysis of Household Food Waste—Development of a Methodology Compatible with the Aims of SDG12.3. Sustainability. 13(15), 8576, https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158576 (2021).

United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021. Nairobi. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (2021).

Nicholes, M. J., Quested, T. E., Reynolds, C., Gillick, S. & Parry, A. D. Surely you don’t eat parsnip skins? Categorising the edibility of food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 147, 179–188, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.004 (2019).

Vincent, A. et al. FAO/INFOODS Food Composition Table for Western Africa User Guide & Condensed Food Composition Table. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/ca7779b (2020).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO/INFOODS Global Food Composition Database for Fish and Shellfish Version 1.0 - uFiSh1.0. Rome, Italy. Available at https://www.fao.org/infoods/infoods/tables-and-databases/faoinfoods-databases/en/ (2016).

Holland, R., Loveday, D. & Ferguson, K. How much meat to expect from a beef carcass. University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture: Tennessee, TN, USA. Available at https://rutherford.tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/200/2022/05/PB1822-How-Much-Meat-to-Expect-from-a-Beef-Carcass.pdf (2014).

McKiernan, W. A., Gaden, B. & Sundstrom, B. Dressing percentages for cattle. Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/103992/dressing-percentages-for-cattle.pdf (2007).

Kuber, P. & Smith, S. M. From pig to pork chop: How much meat to expect from a butcher hog. Washington State University Extension. Available at https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/2049/2021/02/02.21PorkFabVideoDataFactSheet02.16.2021.pdf (2017).

Indumathi, J., Kumar, M. S., Gnanprakash, M., Babu, A. J. & Reddy, G. B. Comparative study on slaughter characteristics between spent broiler breeder hens and broilers. The Pharma Innovation Journal. 8(7), 153–158, https://www.thepharmajournal.com/archives/2019/vol8issue7/PartC/8-6-178-212.pdf (2019).

Stanisławczyk, R., Żurek, J., Rudy, M. & Gil, M. Influence of Horse Age on Carcass Tissue Composition and Horsemeat Quality: Exploring Nutritional and Health Benefits for Gourmets. Applied Sciences 13(20), 11293, https://doi.org/10.3390/app132011293 (2023).

Meat & Livestock Australia. Sheep assessment manual (January 2017). ISSN 1837-4690. https://www.mla.com.au/globalassets/mla-corporate/prices–markets/documents/minlrs-information-brochures-etc/mla_sheep-assessment-manual_jan-2017.pdf.

Contador, L. et al. Characterization of texture attributes of raw almond using a trained sensory panel. Fruits 70, 231–237, https://doi.org/10.1051/fruits/2015018 (2015).

Akça, Y., Mehmet Sen, S. Studies on selection of walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Gürün. In: Schmidt, H., Kellerhals, M. (eds) Progress in Temperate Fruit Breeding. Developments in Plant Breeding. vol 1. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0467-8_36 (1994).

Esquivel, P. & Jiménez, V. Functional properties of coffee and coffee by-products. Food Research International. 46, 488–495, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2011.05.028 (2012).

Food and Agriculture Organization, Sugar Cane. Land and Water. Available at https://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/en/ (2025).

Dohm, J. et al. The genome of the recently domesticated crop plant sugar beet (Beta vulgaris. Nature 505, 546–549, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12817 (2014).

Mubarak, M. U., Zahir, M., Ahmad, S. & Wakeel, A. Sugar beet yield and industrial sugar contents improved by potassium fertilization under scarce and adequate moisture conditions. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 15(11), 2620–2626, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2095-3119(15)61252-7 (2016).

Gwirtz, J. A. & Garcia‐Casal, M. N. Processing maize flour and corn meal food products. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1312(1), 66–75, https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12299 (2014).

Shafie, N. H. & Esa, N. M. The healing components of rice bran. Functional Foods: Wonder of the World. Evidence-Based Functional Foods in Health & Disease, 341–368, ISBN: 978-967-344-737-4 (2017).

Lebert, L., Buche, F., Sorin, A. & Aussenac, T. The wheat aleurone layer: optimisation of its benefits and application to bakery products. Foods 11(22), 3552, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11223552 (2022).

Food and Agriculture Organization. Domestic Animal Diversity Information System (DAD-IS). https://www.fao.org/dad-is/en/. “Dataset downloaded: Data export – breeds” (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for their comments that helped improve the manuscript and the quality of this dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C. led the methodological development of this study, the data collection process, as well as the writing of the manuscript. T.S.H. assisted in the data collection and data validation process. M.D. assisted in the data collection process. S.R. assisted in the data collection process. J.M.M. contributed to the writing of the manuscript, refining and polishing the narrative, and provided guidance during the project. All authors discussed the results, contributed to the final manuscript, and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coudard, A., Szabo-Hemmings, T., Honorine Delval, M. et al. The FOod Commodity composition for Waste qUantification and valorization opportunitieS (FOWCUS) Dataset. Sci Data 12, 1553 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05629-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05629-x