Abstract

The rapid decline in global biodiversity highlights the urgent need for conservation efforts, with botanical gardens playing a crucial role in ex situ plant preservation. Monumental plants, such as the 400-year-old Goethe’s Palm (Chamaerops humilis L.) at the Padua Botanical Garden serve as vital flagship species with significant ecological and cultural value. In this study, we present the first chromosome-level genome assembly of C. humilis, using PacBio HiFi and Arima Hi-C sequencing technologies. The assembled genome spans 4.41 Gbp with a scaffold N50 length of 195 Mbp and it includes 18 pseudo-chromosomes. Repetitive elements constituted approximately 88% of the genome, with Long Terminal Repeats (LTR) alone comprising 63%. A total of 28,321 protein-coding genes were predicted and annotated. The Goethe’s Palm genome assembly is a valuable resource for exploring both its cultural and historical significance, as well as the genetic basis of adaptive traits that allow this palm to thrive in Mediterranean environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Biodiversity is undergoing a rapid global decline, underscoring the urgent need for effective conservation measures to safeguard plant diversity. Botanical gardens worldwide are pivotal in this effort, conserving an estimated 100,000 plant species ex situ1. Beyond their roles in recreation, education, and public engagement, these institutions serve as critical hubs for conservation and research, advancing integrated programs aimed at preventing plant extinctions2.

Monumental trees—large, ancient, or historically significant plants that are notable for their size, age, rarity, or cultural importance3—, serve as powerful flagship species for conservation initiatives. These trees are not merely ecological relics; they are also invaluable cultural and educational resources3,4 and represent unique models for studying long-term adaptation responses.

In the field of conservation genomics, these ancient plants can play crucial roles in the new era of reference genomes5, bridging the gap between modern genomic techniques and traditional conservation efforts. This allows researchers to uncover how monumental trees have adapted to survive through centuries of environmental changes. For instance, the genome sequencing of the Napoleon Oak (Quercus robur L.) in Switzerland revealed remarkable genetic stability, with low levels of somatic mutations even in an ancient tree6. This suggests robust mechanisms for maintaining genetic integrity – a likely contributor to the oak’s long lifespan. Similarly, the Vouves Olive tree (Olea europaea L.) in Greece, estimated to be between 3,000 and 5,000 years old, provided critical genetic insights through genome sequencing7. Researchers identified different genetic origins in the tree’s rootstock and scion, indicating the use of ancient grafting techniques.

From a scientific and biogeographical perspective, the palm species Chamaerops humilis L. (Arecaceae) is crucial for understanding the adaptive traits that allow this palm to thrive in Mediterranean environments. The Mediterranean habitat in which it is endemic differs significantly from the tropical settings typically associated with palms. This makes C. humilis the northmost naturally thriving palm species8. Although currently listed as ‘Least Concern’ by the IUCN Red List9, C. humilis is increasingly under threat from habitat loss, urbanization, and agricultural expansion, contributing to population declines in the wild10,11. As a Pleistocene relict and a thermo-Mediterranean bioindicator12, conserving this species is essential for maintaining the genetic diversity and ecological legacy of Mediterranean ecosystems.

From a historical perspective, Goethe’s Palm represents both a cultural icon and a scientific landmark. During his visit to Padua in 1786, the polymath and writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was inspired by this palm to develop his foundational botanical concepts featured in his scientific book, The Metamorphosis of Plants13. Sequencing the genome of Goethe’s palm may help clarify its provenance, as the original source of the specimen cultivated in 1585 remains unknown.

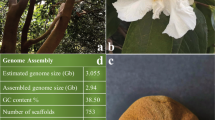

In this study, we present the first chromosome-level genome assembly of C. humilis, generated from Goethe’s Palm (Fig. 1), the oldest known individual of the species housed at the UNESCO Botanical Garden of the University of Padua (Italy)14. The assembled genome spans 4.41 Gbp, with a scaffold N50 of 195 Mbp, and BUSCO completeness of 99.3%. Mapping evaluation shows that 99.98% of HiFi reads aligned to the primary assembly, achieving a total coverage of 17x. The assembly has a quality value (QV) of 59 and an LTR Assembly Index (LAI) of 8.01. Approximately 88% of the genome is composed of repeats, with LTR retrotransposons being the most prevalent. A total of 28,321 protein-coding genes are predicted, 98.5% of which are functionally annotated. This genome provides a comprehensive resource for molecular research on C. humilis and offers novel insights into both the evolutionary history and cultural legacy of this emblematic specimen.

Methods and Results

PacBio and Hi-C sequencing

One fresh leaf of Goethe’s Palm was collected at the Botanical Garden of the University of Padua in September 2022. After 5 days in the dark, the DNA was extracted from approximately 30 mg of leaf tissue according to the CTAB-based protocol15. DNA concentration and DNA fragment length were assessed using the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay kit on the Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and the Genomic DNA Screen Tape on the Agilent 2200 TapeStation system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA), respectively. One SMRTbell library was constructed following the instructions of the SMRTbell Express Prep kit v.2.0 (Pacific Biosciences of California, Inc., Menlo Park, USA). The same library was loaded twice on the PacBio by performing two SMRT cell sequencing runs on the Sequel System IIe in CCS mode. This resulted in an output of 114 Gb of PacBio raw reads, with a read N50 of 14,450 bp and a mean length of 12,812 bp.

We then employed a Hi-C approach to obtain high-resolution data on the spatial organization of the genome, which is essential for precise genome scaffolding. The Hi-C library was prepared from approximately 250 mg of leaf tissue (from the same individual) using the Arima High Coverage Hi-C Kit v.01 (Arima Genomics, Carlsbad, USA) according to the Animal Tissue User Guide. This kit captures the organizational structure of chromatin in three dimensions by first fixing the chromatin structure using formaldehyde, then digesting the crosslinked chromatin using a restriction enzyme cocktail optimized for coverage uniformity across a wide range of genomic sequence compositions and finally ligating the ends of the molecules in close proximity using a biotin-labeled bridge. Library preparation of the proximally-ligated DNA was then performed according to the Swift Biosciences Accel-NGS 2S Plus DNA Library Kit protocol (Swift Biosciences, Ann Arbor, USA). Fragment size distribution and concentration of the Arima High Coverage Hi-C library were assessed using the TapeStation 2200 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) and the Qubit Fluorometer and Qubit dsDNA HS Reagents Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), respectively. The library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform at Novogene (Cambridge, UK) using a 150 bp paired-end sequencing strategy with an insert size of 350 bp, resulting in 97.4 Gb of data.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Four different tissues (young and old leaves, marrow, fruits, and roots) of C. humilis were collected for RNA extraction. Total RNA (including microRNA and mRNA) was extracted using CTAB extraction buffer16 and subsequently quantified with an Implen NanoPhotometer (Implen GmbH, Munich, Germany). Only the samples with 260/280 and 260/230 absorbance ratios above 1.8 were kept. For each sample, 10 µg of total RNA were treated with DNase I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, USA) to remove contaminant DNA and purified with an RNA Clean & Concentration-5 kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, USA).

The RNA extracts were then pooled, and the library preparation for both microRNAs and mRNA, as well as the sequencing, were performed at Novogene (Cambridge, UK). Sequencing was performed on the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, USA), generating 150 bp paired-end reads with an insert size of 350 bp. The sequencing generated 11 Gb of paired-end mRNA raw data, and 1.2 Gb of microRNA data.

Nuclear genome assembly and scaffolding

High-quality circular consensus sequences based on the PacBio subreads were generated using a workflow containing DeepConsensus (v 0.2.0)17. Briefly, all CCS reads were obtained from subreads using PacBio’s ccs tool (v 6.4.0, https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/ccs). Both the CCS reads and subreads were then aligned with actc (v 0.3.1, https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/actc). DeepConsensus was run using CCS reads and alignments. The long high-fidelity (HiFi) fragments generated were first trimmed from potential adapters with HiFiAdapterFilt (v 2.0.1)18 and subsequently assembled at the contig level with Hifiasm (v 0.18.7)19.

We scaffolded the primary and haplotype contig-level assemblies with Hi-C data to generate chromosome-level assemblies. This was carried out using the Arima Hi-C mapping pipeline20. In brief, the Hi-C reads were first aligned to the contigs using BWA-MEM (v 0.7.17)21. The 3′ ends of the reads identified as chimeric were then removed with Arima in-house perl script (part of the Arima Hi-C mapping pipeline). Next, duplicated reads were removed with Picard (v 3.0.0)22. Finally, the assembly was scaffolded to chromosome level using YaHS (v 1.1)23 and visualized for quality assessment with Juicebox (v 1.11.08)24. To fill gaps, TGS-GapCloser (v 1.0.1)25 was run with Racon (v 1.4.3)26 as a method for enhancing the base-level accuracy of merged sequences. The chromosome-level genome assembly and the HiFi reads were utilized as the input for TGS-GapCloser.

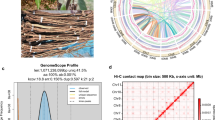

To enhance the quality of the genome assemblies, the Arima Hi-C mapping pipeline was run once more, using the output from the initial run as input. The subsequent steps involved gap closing and quality assessment of the assemblies obtained. After two iterations of the Arima Hi-C mapping pipeline, the assemblies of the primary and the two haplotypes decreased their total number of scaffolds, increased the scaffold N90 (Table S1, Table S2, Table S3), and converged into 18 main scaffolds. These 18 scaffolds displayed on the contact maps (Fig. S1) are consistent with the findings of Röser27, who identified 18 chromosome pairs in C. humilis. The GC content remained the same throughout all the iterations, being 43.8% in all the assemblies (Table S1, Table S2, Table S3). The primary assembly had a total length of 4.41 Gbp, with 1,986 scaffolds, scaffold N50 of 195 Mbp, and BUSCO completeness of 99.3% (Table 1, Table S1, Fig. 2). The statistics for both haplotypes can be found in Tables S2 and S3.

(a) Ideogram showing the telomeres (red), centromeres (black), and the microRNA annotated (orange, light blue, and dark blue). Chromosomes in the ideogram were sorted from the longest (chr 1) to the shortest one (chr 18). (b) Proteomap displaying the KEGG functional annotation groups. (c) SnailPlot showing the primary assembly statistics. (d) JupiterPlots showing the synteny between the primary and each haplotype assemblies, and between haplotypes.

We then used Blobtools (v 1.1.1)28 to identify potential contamination. To do so, the high-quality HiFi reads were mapped against each assembly using Minimap2 (v 2.26)29, and the scaffolds of the assembly were blasted against the NCBI Nucleotide database with Blastn (v 2.14.0)30. No evident contamination was found in any of the assemblies (Fig. S2). Finally, the statistics of the primary genome assembly were summarized in a snail plot (Fig. 2), which was obtained using Blobtoolkit (v 4.2.1)31.

We identified telomeres and centromeres of the primary assembly with quarTeT (v 1.2.5)32 and CentrIER (v 2.0)33, respectively. The default parameters were used for all functions except for telomere identification, where the ‘-m 10’ parameter was employed. The default motif for telomere identification established by quarTeT was TTTAGGG. The results were then visualized in an ideogram plot using the ggplot234 R package. In the primary assembly, all telomeres were identified (≥10 repeats), except for chromosome 7, which was missing one telomere. Likewise, all putative centromeres were detected, except for chromosome 10 (Fig. 2).

Transcriptome assembly and quality assessment

Raw reads from the RNA sequencing data (microRNA and mRNA) were first trimmed with Fastp (v 0.23.4)35. A total of 97.7% of the paired-end mRNA and 99.8% of microRNA passed length and quality filtering. They were subsequently aligned to the primary chromosome-level assembly with HISAT2 (v 2.2.1)36. Each type of RNA was assembled with StringTie (v 2.1.2)37.

Additionally, the microRNAs were aligned and annotated using ShortStack (v 4.0.3)38 with microRNAanno as a reference dataset39. The results were then plotted in an ideogram generated with the ggplot234 R package. The annotation identified 13 known miRNAs, 47 putative miRNAs, and 4 different siRNAs (Table S4). Identified miRNAs included miR156, miR159, miR160, miR164, miR166, miR167, miR168, miR172, miR395, miR396, miR528, miR535, and miR5179, and the siRNA were siRNA21, siRNA22, siRNA23, and siRNA24.

Repeat annotation of the primary assembly

To enhance the accuracy of gene prediction, repeat regions in the primary assembly were first masked using both the de novo Viridiplantae repeat library in RepeatModeler (v 2.0.5)40 and the Liliopsida repeat library from RepBase41 using RepeatMasker (v 4.1.6)42. The Liliopsida library was selected because C. humilis belongs to this taxonomic group, making it the closest available clade. Given the significant impact of masking on gene prediction, two different masking procedures were applied using RepeatMasker (v 4.1.6)42: (i) simple repeats were soft-masked while interspersed repeats were hard-masked, and (ii) all repeats were soft-masked.

Genome masking revealed that 88% of the genome assembly consists of repeats (Table S5). LTR retrotransposons represented most of the transposable elements in C. humilis (63%), primarily composed of two superfamilies: Ty1/Copia (38%) and Gypsy (25%). Other repeat classes, such as DNA transposons, small RNA, simple repeats, and others, collectively accounted for less than 10% (Table 1, Table S5).

Gene annotation of the primary assembly

Gene annotation was performed with both BRAKER343 and GeMoMa (v 1.9)44 using (i) the mRNA sequences mapped to the primary assembly, (ii) the reference genomes of Elaeis guineensis Jacq. (GCA_000442705.1, African oil palm) and Phoenix dactylifera L. (GCA_009389715.1, date palm), and (iii) the masked primary assembly. To run BRAKER3, we used the soft-masked genome, whereas for GeMoMA, we used the hard-masked genome, as required by each tool. The output of both tools was then combined with previously generated transcriptomic data to obtain a consensus gene annotation using EVidenceModeler (v 2.1.0)45. The primary genome assembly resulted in 28,321 annotated genes.

Additionally, the functional annotation of the predicted proteins was conducted by (i) Blastp (v 2.14.0)30 search using an E-value cutoff of 10−6 against the Swiss-Prot database, and (ii) InterProScan (v 5.64−96.0)46. A total of 24,116 (85%) proteins were identified in the Swiss-Prot database while 27,905 (98.5%) were identified by InterProScan, of which 21,386 (76%) had a gene ontology (GO) term associated.

To search for homology between the proteins, the sequence similarity between all protein-coding genes was compared using DIAMOND (v 0.9.30)47. For a protein sequence, the best five hits that met an E-value threshold of 10−5 were reported. The file generated was employed in conjunction with the annotation file to execute MCScanX (v 1.0)48 to generate pairwise synteny blocks of proteins. To identify the number and type of duplicated proteins, we ran the function ‘Duplicate_gene_classifier’ from MCScanX (v 1.0)48. This analysis provided the following classification of the duplicated proteins: 3,128 were singletons, 1,709 were proximal (located in nearby chromosomal regions but not adjacent), 3,986 were tandem (consecutive repeat), 12,330 were whole-genome or segmental (matching genes in synteny blocks), and 7,169 were dispersed (any mode other than segmental, tandem and proximal) duplications.

Additionally, the script ‘group_collinear_genes.pl’ from MCScanX (v 1.0)48 was applied to cluster the proteins by connecting collinear proteins until no protein in each group had any collinear proteins outside the group. A total of 4,017 collinear groups were found, which were visualized with SynVisio49 software (Fig. S3).

Organelle assembly and annotation

The most suitable reference genome for the assembly of the mitochondria and the chloroplast was identified using the script ‘findMitoReference.py’50. After assembling the genomes (as described above), all contigs belonging to the organelles were identified from the primary chromosome-level assembly using Blastn (v 2.14.0)30 and removed with Seqtk (v 1.3)51. Both organelle assemblies were annotated using GeSeq (v 2.03)52, setting the sequence identity for the proteins, rRNA, and tRNA to 95%. In addition, we utilized all NCBI Refseq assemblies from the Arecaceae family as references for the organelles GeSeq annotation. The results were visualized with OGDRAW (v 1.3.1)53.

Mitochondrial genome assembly

The mitochondrial genome was assembled with MitoHiFi (v 3.2)50, using the most closely related reference genome, Phoenix dactylifera L. (Arecaceae, NC_016740), and the primary chromosome-level assembly. We obtained a circular mitochondrial genome with a total length of 522.6 Kbp and GC content of 45.71% (Table S6). The mitochondrial assembly was annotated using MitoHiFi (v 3.2)50 and GeSeq (v 2.03)52. The annotation with the GeSeq (v 2.03)52 was performed using BLAT annotation engine (BLATX and BLATN). MitoHifi annotated 53 unique genes (Fig. S4), while GeSeq annotated between 37 and 41 genes (Table S7, Fig. S5). Due to the absence of other mitochondrial genomes for C. humilis in NCBI, the available ones from other members of the Arecaceae family were downloaded (Table S7). The statistics generated by Quast (v 5.0.2)54 showed that C. humilis has a GC content comparable to that of related species. In contrast, GeSeq (v 2.03)52 revealed notable differences in gene content across species (Table S7).

Chloroplast genome assembly

The chloroplast genome was assembled using ptGAUL (v 1.0.5)55, with C. humilis (Arecaceae, ON248747) as the most closely related reference genome, and PacBio HiFi reads as input. The GeSeq (v 2.03)52 with Chlöe engine was used for the gene annotation. We obtained a chloroplast assembly with a total length of 159 Kbp and a GC content of 37.17% (Table S8). It displays the typical quadripartite structure, comprising a large single-copy region (LSC; 86,302 bp), a small single-copy region (SSC; 17,924 bp) and two inverted repeats (IRs; 27,241 bp each). The genome contains 112 unique genes according to the GeSeq annotation (Fig. S5, Table S8). The statistics from Quast (v 5.0.2)54 indicate that both genome length and GC content are in line with other C. humilis plastome assemblies available in NCBI. The number of genes predicted using PGA (Plastid Genome Annotator)56 is likewise consistent across assemblies (Table S8).

Comparison to other published palm genomes

The genomes of 15 palm specimens belonging to eight different species were downloaded from NCBI, and statistics for each of them (assembly length, N50, and GC content) were calculated with Quast (v 5.0.2)54 (Table S9). BUSCO (v 5.2.2)57 with the ‘Liliopsida_odb10’ dataset was used to quantify complete and single-copy BUSCO genes of these palm genomes. Only genomes with more than 50% completeness were selected for the BUSCO-based phylogenomic analysis.

The phylogenomic position of C. humilis with respect to the other related palm species was determined with ‘BUSCO_phylogenomics.py’ (https://github.com/jamiemcg/BUSCO_phylogenomics). In short, this pipeline aligned the BUSCO sequences with MUSCLE (v 5.1)58, trimmed them with TrimAl (v 1.4.1)59, and constructed a maximum-likelihood consensus tree with IQ-TREE (v 2.2.6)60. The genomes of Aegilops tauschii subsp. strangulata (GCF_002575655.2) and Zea mays (GCF_902167145.1) were used as outgroups. All genomes from the same species were monophyletic with high clade support (bootstrap support of 100, Fig. S6). Chamaerops humilis (18 chromosomes) is sister to the genus Phoenix (with 18−19 chromosomes), which includes two species, P. dactylifera and P. roebelenii. There are two other clades: one comprising the genera Calamus and Metroxylon, and another comprising the genera Areca, Elaeis and Cocos (each with 16 chromosomes). The phylogenetic reconstruction showed a strong phylogenetic signal for chromosome number, but there was no correlation between assembly size and chromosome number61 (Table S9, Fig. S6).

To assess the transposable elements (TE) activity, we calculated the percentage of LTRs for each palm species. For species with multiple genome assemblies, the most complete assembly was selected based on BUSCO scores (Table S9). The proportion of LTR elements was determined by using RepeatMasker (v 4.1.6)42 as described above. This method involved the integration of the de novo Viridiplantae repeat library from RepeatModeler (v 2.0.5)40 and the Liliopsida repeat library from RepBase41. The proportion of LTR elements from the RepeatMasker-generated table was used to build a linear regression model to examine its linear relationship with the assembly length. Repeat divergence landscapes were then created following the methodology of Rodriguez and Arkhipova (2023)62, using TwoBit (v 2.0.9, weng-lab.github.io/TwoBit/), and two Perl scripts (calcDivergenceFromAlign.pl and createRepeatLandscape.pl) from RepeatMasker (v 4.1.6)42. The results were presented in the form of a histogram created using the ggplot234 R package. Small genomes such as those from Phoenix or Metroxylon have lower proportions of LTR elements than larger ones like those from Chamaerops or Areca (Table S9, Fig. 3). The repeat divergence landscape plots (Fig. 3, Fig. S7) show that the elevated proportion of TE sequences in C. humilis is associated with low sequence divergence, particularly within the LTR family.

(a) Linear regression between assembly length and proportion of LTR elements present in the genome. The linear regression shows an adjusted R2 of 0.74 (p-value = 1.08e-5), with a residual standard error of 0.54. (b) Repeat divergence landscapes of LTR elements in the main crops of the family Arecaceae.

Geographical origin of Goethe’s Palm

The ten highly polymorphic microsatellites identified by Giovino et al.11 were used in this study to investigate the geographic origin of Goethe’s Palm. Microsatellite loci were extracted from the haplotype 1 and haplotype 2 chromosome-level assemblies of C. humilis using SeqKit (v 0.10.2)63 and Blastn (v 2.14.0)30. Eight loci were detected in Goethe’s Palm (locus 15, locus 16, locus 19, locus 23, locus 25, locus 27, locus 37 and locus 44). Locus 25 was only found in haplotype 1, while locus 37 was only present in haplotype 2.

The identified loci were combined with the Giovino et al.11 dataset, which includes approximately 300 individuals spanning the native range of C. humilis. A genind object was constructed using the adegenet64 R package, and duplicate genotypes were removed with poppr65. The resulting dataset was analyzed using Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC), which explained 77% of the genetic variation and revealed a strong geographic structure, with axis 1 separating western and eastern Mediterranean populations (Fig. 4). The results were then visualized using the ‘compoplot’ function from adegenet64 and ggplot234. Goethe’s Palm grouped with the Western genetic lineage, predominantly found in Spain and Portugal (Fig. 4).

(a) DAPC showing population structure in populations of the Mediterranean dwarf palm and the potential geographic origin of Goethe’s Palm. All samples analyzed represented by filled circles are colored according to the country to which they belong. (b) Compoplot showing the most likely assignment of Goethe’s Palm to the evaluated countries. Both analyses indicate that Goethe’s Palm belongs to the Western genetic lineage of C. humilis.

Data Records

The C. humilis genome assembly was deposited in NCBI GenBank under accession number GCA_042465325.166 for haplotype 1, GCA_042465335.167 for haplotype 2, and GCA_042465385.168 for the primary assembly. The RNA sequencing data69 was submitted to the NCBI Genbank under the accession numbers SRR29081397 and SRR29081396 for mRNA and microRNA, respectively. The mitochondrial and plastid assemblies were deposited in the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14872859)70. The primary assembly annotation was deposited in the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15518854)71.

Technical Validation

The statistics for the nuclear (Table S1, Table S2, Table S3) and organelle (Table S6, Table S7, Table S8) assemblies were obtained using Quast (v 5.0.2)54 and Assemblathon272.

The completeness of the genome assemblies was analyzed using BUSCO (v 5.2.2)57 with the ‘Viridiplantae_odb10’ dataset. The primary assembly had a total BUSCO completeness of 99.3% (Table S1, Fig. 2). The BUSCO completeness of haplotype1 and haplotype 2 are shown in Table S2 and Table S3, respectively. The completeness of the predicted proteins was also evaluated with BUSCO, yielding 98.3% completeness (C: 98.3% [S: 88.7% and D: 9.6%], F: 0.7%, M: 1.0%). Finally, the BUSCO completeness of the transcripts obtained after assembling the mRNA data with StringTie (v 2.1.2)37 reached 91.8% (Table S10).

For the primary assembly, mapping rate and coverage depth were assessed using Qualimap (v 2.3)73. The analysis showed that 99.98% of HiFi reads mapped to the primary genome assembly with an average coverage of 17x. Furthermore, the LTR Assembly Index (LAI), calculated using LTR retriever (v 3.0.1)74, yielded a value of 8.01.

To evaluate annotation quality, mRNA reads were mapped to the primary genome using BBmap (v 39.06)75, resulting in a 98% mapping rate.

To evaluate synteny between the primary assembly and each haplotype, as well as between the two haplotypes, we ran JupiterPlot (v 3.8.1)76. The JupiterPlots showed high levels of synteny between the primary and haplotype 1 assemblies, and between the primary and haplotype 2 assemblies, as expected given the identical chromosome numbers (Fig. 2). However, the synteny between the two haplotypes revealed that scaffolds 17 and 18 were incomplete in haplotype 2.

In addition, the haplotype assemblies were assessed using Merqury (v 1.3)77. For this analysis, Meryl was first run with the HiFi reads using a k-mer size of 21. Subsequently, Merqury was executed with default parameters. The k-mer completeness corroborated the results obtained by the synteny analysis. Specifically, the k-mer completeness for haplotype 1 was higher, reaching 83%, while for haplotype 2, it reached 82%. For the primary assembly, k-mer completeness reached 87% and the quality value (QV) reached 59%.

Code availability

All commands used in data processing and analysis were performed according to the developers’ recommendations. No custom code was used in this study.

References

Mounce, R., Smith, P. & Brockington, S. Ex situ conservation of plant diversity in the world’s botanic gardens. Nature plants 3(10), 795–802, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-017-0019-3 (2017).

Antonelli, A. et al. Why plant diversity and distribution matter. The New phytologist 240(4), 1331–1336, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19282 (2023).

Cannizzaro, S. & Corinto, G. L. The Role of Monumental Trees in Defining Local Identity and in Tourism. A case study in the Marches region. Geoprogress Journal 1(1), 29–48 (2014).

Vannuccini, M., Giachini, M., Giorgi, D. & Ferretti R. Monumental trees inventories at different scales: objectives and perspectives. In: Urban Forestry: bridging cultures, disciplines old attitudes and new demands, 9th European Forum on Urban Forestry, Proceedings. 99 pp. (2006).

Formenti, G. et al. European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) Consortium. The era of reference genomes in conservation genomics. Trends in ecology and evolution, 37(3), 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.11.008 (2022).

Schmid-Siegert, E. et al. Low number of fixed somatic mutations in a long-lived oak tree. Nature plants 3(12), 926–929, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-017-0066-9 (2017).

Bombarely, A. et al. Elucidation of the origin of the monumental olive tree of Vouves in Crete, Greece. Plants 10(11), 2374, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10112374 (2021).

García-Castaño, J. L., Terrab, A., Ortiz, M. A., Stuessy, T. F. & Talavera, S. Patterns of phylogeography and vicariance of Chamaerops humilis L. (Palmae). Turkish Journal of Botany 38, 1132–1146, https://doi.org/10.3906/BOT-1404-38 (2014).

IUCN. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1. Second edition. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. iv + 32 pp. (2012).

Nekhla, H. et al. The ecological importance of Chamaerops humilis steppe for animal biodiversity in Northwest Africa (Morocco). Zoology and Ecology 32(1), 74–83, https://doi.org/10.35513/21658005.2022.1.9 (2022).

Giovino, A. et al. Genetic variability of Chamaerops humilis (Arecaceae) throughout its native range highlights two species movement pathways from its area of origin. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 201, 361–376, https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/boac053 (2023).

Herrera, J. On the reproductive biology of the dwarf palm, Chamaerops humilis in Southern Spain. Principes 33, 27–32 (1989).

von Goethe, J.W. The Metamorphosis of the Plants. Reprinted in 2009 (Cambridge: MIT Press) (1790).

Hodge, W. H. Goethe’s Palm. Principes 26(41), 194–199 (1982).

Murray, M. G. & Thompson, W. F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic acids research 8(19), 4321–4325, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/8.19.4321 (1980).

Chang, S., Puryear, J. D. & Cairney, J. W. A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 11, 113–116, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02670468 (1993).

Baid, G. et al. DeepConsensus improves the accuracy of sequences with a gap-aware sequence transformer. Nature Biotechnology 41, 232–238, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01435-7 (2023).

Sim, S. B., Corpuz, R. L., Simmonds, T. J. & Geib, S. M. HiFiAdapterFilt, a memory efficient read processing pipeline, prevents occurrence of adapter sequence in PacBio HiFi reads and their negative impacts on genome assembly. BMC Genomics 23, 157, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08375-1 (2022).

Cheng, H. et al. Haplotype-resolved assembly of diploid genomes without parental data. Nature Biotechnology 40, 1332–1335, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01261-x (2022).

Arima Genomics, Inc. Arima-HiC Mapping Pipeline. San Diego, GitHub. https://github.com/ArimaGenomics/mapping_pipeline/blob/master/Arima_Mapping_UserGuide_A160156_v03.pdf (2023)

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. ArXiv 3, 13033997, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997 (2013).

Picard Toolkit. Broad Institute, GitHub Repository. https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/; Broad Institute (2019).

Zhou, C., McCarthy, S. A. & Durbin, R. YaHS: yet another Hi-C scaffolding tool. Bioinformatics 39, btac808, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac808 (2023).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Juicebox.js provides a cloud-based visualization system for Hi-C data. Cell Systems 6, 256–258.e1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2018.01.001 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. TGS-GapCloser: A fast and accurate gap closer for large genomes with low coverage of error-prone long reads. GigaScience 9, giaa094, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa094 (2020).

Vaser, R., Sović, I., Nagarajan, N. & Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Research 27, 737–746, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.214270.116 (2017).

Röser, M. Variation and evolution of karyotype characters in palm subfamily Coryphoideae s.l. Acta Botanica 106, 170–182, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1438-8677.1993.tb00354.x (1993).

Laetsch, D. R. & Blaxter, M. L. BlobTools: Interrogation of genome assemblies. F1000Res 6, 1287, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.12232.1 (2017).

Li, H. New strategies to improve minimap2 alignment accuracy. Bioinformatics 37, 4572–4574, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btab705 (2021).

McGinnis, S. & Madden, T. L. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research 32, W20–W25, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh435 (2004).

Challis, R., Richards, E., Rajan, J., Cochrane, G. & Blaxter, M. BlobToolKit − Interactive quality assessment of genome assemblies. G3 10, 1361–1374, https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.119.400908 (2020).

Lin, Y. et al. QuarTeT: a telomere-to-telomere toolkit for gap-free genome assembly and centromeric repeat identification. Horticulture research 10(8), uhad127, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhad127 (2023).

Xu, D. et al. CentIER: Accurate centromere identification for plant genomes. Plant communications 5(10), 101046, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2024.101046 (2024).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4, https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (2016).

Chen, S. Ultrafast one‐pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. Imeta 2, e107, https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.107 (2023).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnology 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Shumate, A., Wong, B., Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. Improved transcriptome assembly using a hybrid of long and short reads with StringTie. PLoS Computational Biology 18, e1009730, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009730 (2022).

Axtell, M. J. ShortStack: comprehensive annotation and quantification of small RNA genes. RNA 19(6), 740–751, https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.035279.112 (2013).

Chen, C. et al. sRNAanno − A database repository of uniformly annotated small RNAs in plants. Horticulture Research 8, 45, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-021-00480-8 (2021).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenetic and genome research 110, 462–467, https://doi.org/10.1159/000084979 (2005).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current protocols in bioinformatics Chapter 4, 4.10.1–4.10.14, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Gabriel, L. et al. BRAKER3: Fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome research 34(5), 769–777, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.278090.123 (2024).

Keilwagen, J., Hartung, F., Paulini, M., Twardziok, S. O. & Grau, J. Combining RNA-seq data and homology-based gene prediction for plants, animals, and fungi. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 189, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-018-2203-5 (2018).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome biology 9(1), R7, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 (2014).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H. G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nature methods 18(4), 366–368, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic acids research 40(7), e49, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr1293 (2012).

Bandi, V., Gutwin, C. Interactive exploration of genomic conservation. In Proceedings of the 46th Graphics Interface Conference on Proceedings of Graphics Interface 2020 (GI’20). Canadian Human-Computer Communications Society, Waterloo, CAN (2020).

Uliano-Silva, M. et al. MitoHiFi: a python pipeline for mitochondrial genome assembly from PacBio high fidelity reads. BMC Bioinformatics 24, 288, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-023-05385-y (2023).

Li, H. (2012). Seqtk Toolkit for processing sequences in FASTA/Q formats. GitHub, 767−769.

Tillich, M. et al. GeSeq – versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 45, W6–W11, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx391 (2017).

Greiner, S., Lehwark, P. & Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic acids research 47(W1), W59–W64, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz238 (2019).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 (2013).

Zhou, W. et al. PlasTid Genome Assembly Using Long-read data. ptGAUL). BioRxiv 23, 1442–1457, https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13787 (2022).

Qu, X. J., Moore, M. J., Li, D. Z. & Yi, T. S. PGA: a software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods 15, 50, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-019-0435-7 (2019).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: Novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 4647–4654, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab199 (2021).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE 5: High-accuracy alignment ensembles enable unbiased assessments of sequence homology and phylogeny. Nature Communications 13, 6968, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34630-w (2022).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. TrimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348 (2009).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32, 268–274, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300 (2015).

Barrett, C. F. et al. Ancient polyploidy and genome evolution in palms. Genome biology and evolution 11, 1501–1511, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evz092 (2019).

Rodriguez, F. & Arkhipova, I. R. An overview of best practices for transposable element identification, classification, and annotation in eukaryotic genomes. Methods in Molecular Biology 2607, 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2883-6_1 (2023).

Shen, W., Le, S., Li, Y. & Hu, F. SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PloS one 11(10), e0163962, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163962 (2016).

Jombart, T. Adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24(11), 1403–1405, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn129 (2008).

Kamvar, Z. N., Tabima, J. F. & Grünwald, N. J. Poppr: An R package for genetic analysis of populations with clonal, partially clonal, and/or sexual reproduction. PeerJ 2, e281, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.281 (2014).

Botanical Garden of Padova. Genome assembly ASM4246532v1. Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_042465325.1 (2024).

Botanical Garden of Padova. Genome assembly ASM4246533v1. Genbank. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_042465335.1 (2024).

Botanical Garden of Padova. Genome assembly ASM4246538v1. Genbank. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_042465385.1 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP508617 (2024).

Beltran-Sanz, N. Sequencing a botanical monument: a chromosome-level assembly of the 400-year-old Goethe’s Palm (Chamaerops humilis L.) at the Botanical Garden of the University of Padua (Italy) [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14872859 (2025).

Beltran-Sanz, N. Sequencing a botanical monument: a chromosome-level assembly of the 400-year-old Goethe’s Palm (Chamaerops humilis L.) at the Botanical Garden of the University of Padua (Italy) [Data set], Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15518854 (2025).

Bradnam, K. R. et al. Assemblathon 2: evaluating de novo methods of genome assembly in three vertebrate species. GigaScience 2, 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-217X-2-10 (2013).

Okonechnikov, K., Conesa, A. & García-Alcalde, F. Qualimap 2: advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 32(2), 292–294, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv566 (2016).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR retriever: A highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant physiology 176(2), 1410–1422, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.01310 (2018).

Bushnell, B. BBMap: A Fast, Accurate, Splice-Aware Aligner (2014).

Chu, J. Jupiter Plot: a Circos-based tool to visualize genome assembly consistency. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1241235 (2018).

Rhie, A. et al. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biology 21, 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (LOEWE-TBG), especially Alexander Ben Hamadou and Charlotte Gerheim, for their wet lab support. We acknowledge the Genome Technology Center (RGTC) at Radboudumc for access to the Sequencing Core Facility (Nijmegen, Netherlands), where PacBio SMRT sequencing was performed on the Sequel IIe platform. We are grateful to Rhonda Struminger (Botanical Garden of Padua) for her comments on the manuscript and assistance with English language review. We also thank Carlo Calore and the Ufficio Eventi Permanenti (Botanical Garden of Padua) for providing palm images and the garden map. This project was made possible through the generous support of the University of Oulu and the Research Council of Finland’s Profi6 336449 program, titled ‘Biodiverse Anthropocenes’, the LOEWE-TBG (LOEWE/1/10/519/03/03.001(0014)/52), and the University of Padua (MORO_AFAS22_01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Núria Beltran-Sanz carried out the formal data analysis and drafted the manuscript under the supervision of Francesco Dal Grande and Stefan Prost. Francesco Dal Grande and Tomas Morosinotto developed the conceptual framework of the study. Veronica Malavasi, Silvia Moschin, and Carola Greve conducted the laboratory analyses. Tilman Schell and Stefan Prost provided support with the bioinformatics analyses. Núria Beltran-Sanz, Stefan Prost, and Francesco Dal Grande wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the review process and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beltran-Sanz, N., Prost, S., Malavasi, V. et al. Chromosome-level assembly of the 400-year-old Goethe’s Palm (Chamaerops humilis L.). Sci Data 12, 1542 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05673-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05673-7