Abstract

We present a comprehensive dataset of absorption and reduced scattering spectra collected via time-domain diffuse optical spectroscopy in the 610-1110 nm range, across 10 subjects and on 5 different body locations – the upper arm, the radius-ulna region, the abdomen, the forehead, and the calcaneus. The ultrasound images acquired in the same location are included as well, and along with the demographic information shed useful insights on the inter-subject variability. The dataset, openly available in Zenodo, contains the raw data, the meta data, the tools to operate on them, and can be exploited to devise light-based diagnostics or therapeutic techniques, to appreciate biological variability, and also to test different models of photon migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

“In God we trust, all others must bring data”. Indeed, as W. Edwards Deming put it, in today’s scientific world the importance of data cannot be undermined. Keeping up with the rapid progression of science requires an exchange of complex knowledge backed by the presence of accessible data.

Large compiled databases of ex-vivo optical interaction properties of several biological tissues already exist and are a key resource for researchers. Yet, there are several factors and limitations which confound the appropriate application of the data within the research community. Significant amongst these factors are differences between ex-vivo and in-vivo properties, differences between human and animal specimens, lack of standardization and inconsistencies amongst various studies, frequent limitation of measurements to a few discrete wavelengths, a limited number of subjects that do not permit to account for biological variability, and in general not easy access to the underlying data. Furthermore, on the side of in-vivo optical properties of humans, few studies report bulk properties over a wide continuous spectral range, and definitely the availability of open datasets, including the underlying raw data and metadata, is largely insufficient. In the recent times, there have been many publications of ‘Data descriptor articles’ describing complete datasets (including raw data) pertaining to in-vivo spectra and diffuse optics, and some examples are provided below. Some of these describe diffuse optical tomographic datasets monitoring brain function during a task (58 subjects)1, or in resting state (28 subjects)2; while others contain broadband spectra obtained using CW diffuse optical techniques for in-vivo campaigns (20 subjects)3 and ex-vivo animal tissues4; or similar spectroscopic techniques such as spectral imaging (10 subjects5, autofluorescence (131 subjects)6 or hyperspectral imaging (193 subjects)7. Furthermore, dedicated repositories for fNIRS and diffusive-light, neuro-imaging experimental campaigns are available, providing numerous datasets collected from human subjects.8,9,10. With the push for OPEN SCIENCE, and to strengthen the spirit of international scientific collaboration, in the recent times researchers from our group have also been adding the complete raw data along with their publications on the open repository of ZENODO in the format that will be explained in this article. This effort also pioneers the addition of time-domain raw data to the online diffuse optics databases.11,12,13,14.

In this context, this work describes an experimental campaign in the field of diffuse optics, where light in the so-called <<therapeutic window>> (roughly 600–1300 nm) is increasingly being used both for diagnostics and therapeutics due to the deep (≈cm) penetration of photons, possibly due to the low absorption in this spectral range. One drawback is that in biological tissues the absorption (μa) and reduced scattering (\({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\)) coefficients are effectively coupled, and it is not trivial to retrieve them separately. On the other hand, knowledge of in-vivo tissue optical properties is crucial to devise and optimize light-based approaches for diagnostics and therapy.

Time-domain diffuse optical spectroscopy enables to disentangle the absorption from the scattering contributions,15 since the two parameters have quite distinctive effects on the shape of the distribution of the times-of-flight (DTOF): the former affects the decay tail, while the latter mostly acts on the position and the width of the temporal peak.16,17 The optical estimate is not affected by skin pigmentation or by the optical contact in general, and does not require any external calibration. Furthermore, the photon arrival time encodes the depth visiting probability and can be exploited, for instance, for multi-layered reconstructions.

In this study, we measure the absorption and reduced scattering coefficients of in-vivo tissues from 10 subjects with a some variability in gender, age, and skin color, and from 5 body locations: the upper arm, the forearm, the abdomen, the forehead, and the calcaneus in the spectral range of 610-1110 nm. Further, we also present ultrasound images taken at the same locations to better understand the photons localization in the tissues.

In practical terms, this dataset can have many applications. To name just a few: i) as input optical properties for simulations of photon migration; ii) to estimate the penetration depth of photons in tissues, enriched with biological variability; iii) to test theoretical models of photon migration, both homogeneous and heterogeneous; iv) to explore the contribution of key tissue absorbers in the 600-1100 nm range, as well as spectral scattering models; v) to train artificial intelligence networks on physiological and accurate in-vivo data. All these potential uses allow a better understanding of light-tissue interactions and are preliminary to real-life applications. In this light, the data presented here can be of service not only to the community of time-resolved diffuse optical spectroscopy, but also other mainstream techniques - such as photoacoustics, laser speckle imaging, and optical coherence tomography - can benefit from a reliable in-vivo characterization of optical properties. Some examples of applications in the study of photon migration in diffusive media are: retrieving bio-markers of pathological transformation (e.g. cancerous breast lesions),18,19,20,21 monitoring of vital signs (e.g. brain oxygenation),22,23 and in-vivo24,25,26,27,28 and ex-vivo29 tissue characterization. Furthermore, the knowledge of tissue properties and of the depth distribution of photons are relevant for light-based therapeutics, such as photodynamic therapy30 or laser thermal treatment31.

This paper is complemented with an open dataset32 deployed on Zenodo for easy download of our preliminary analysis to recover the spectra, the underlying raw data, and the relevant metadata. We also present the general strategy and template we adopted to streamline the deployment of open data: in fact, seeing a working example of an optimized process could be helpful to other researchers as well, wishing to perform this task in the spirit of Open Science.

Methods

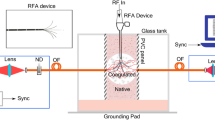

The extended dataset was acquired with a systematic approach, with particular regard for data consistency and reproducibility. The spectra are obtained from time-domain diffuse reflectance data in the 610-1110 nm range at steps of 10 nm, based on the acquisition of the DTOFs of photons propagating into the tissue and collected at a distance of 2 cm from the injection point. For each wavelength we fitted the DTOFs using the diffusion approximation to the radiative transport equation (RTE), which describes the propagation of photons in scattering media, hence reconstructing the optical properties of the tissues across the intended spectral range. Figure 1 exemplifies the design of the experiment. These spectra are then paired with ultrasound (US) images, expanding the informative content of the study. In the following subsections we report the details of the procedures and protocols we observed, from data collection through data analysis, and data representation.

Workflow of the present study. From left to right: schematic representation of the measurement, with light injection/collection in/from the sample highlighted by arrows, and light propagation inside the sample depicted as the typical banana shape of the photon paths; DTOFs are recorded and saved as ‘.DAT’ files - the reported DTOF is for 710 nm from the upper arm of one of the subjects; these curves are fitted to an analytical model of photon propagation through diffusive media and absorption and reduced scattering spectra are recovered.

Optical Setup

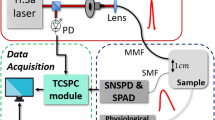

The setup for Time-domain diffuse optical spectroscopy, shown in Fig. 2. uses a supercontinuum fiber laser (SuperK EXTREME EXW-12, NKT Photonics, Denmark) emitting pulsed radiation (picosecond range) in the visible and near-infrared spectral range (450-1750 nm) at a repetition rate of 40 MHz. Maximum available power is 5 W over the full spectral range. Wavelength selection is achieved through the rotation of a Pellin-Broca prism (spectral resolution in the range 2-10 nm); light is then coupled by a lens to an optical fiber which is used to inject the light into the sample. Before the injection into the sample, there is an attenuation stage (variable neutral density filter), completely automated and capable of regulating the amount of light delivered to the sample. The maximum power that can be delivered is in the range 0.5-6 mW. A second optical fiber collects the light emerging from the sample in reflectance geometry, and couples it to a homemade silicon PhotoMultiplier (SiPM) detector33 (S13362-1350DG, Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Japan, 600-1100 nm sensitivity range, temporal jitter ≈ 75 ps). The electrical signal coming from the detector is sent to a time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) board (SPC-130, Becker & Hickl, Germany) to record the arrival time-of-flight of the photons which have propagated through the sample with respect to the trigger signal coming from the laser. Finally, the reconstructed histogram of the time-of-flights over the acquisition time provides a distribution of time-of-flight (DTOF) curve. A scheme of the optical set-up is reported in Fig. 2.

Subjects and ethical approvals

10 subjects were measured in total, with some variability in age, gender, colour of skintone and body habitus. The subjects were informed on the goal of the study and explained the experimental tools to be used for performing the measurements, in the presence of the operator and the leader of the study. Volunteers then signed an informed consent form, along with submitting basic demographic data such as age, gender and the body mass index (BMI). The cohort was composed of 7 male and 3 female subjects with 8 of them in the age group of 20–30 years, while 2 were in between 55–60 years, and 1 of them had a darker skin tone. The major variability was in the BMI, spreading from 18–25. Since this was a study on healthy volunteers, there was no particular inclusion/exclusion criteria applied during selection. Table 1 summarizes the details of each subject, including BMI which gives a rough idea of the body type of an individual.

This study received approval from the ‘Research ethical committee’ of Politecnico di Milano (Approval opinion No. - 22/2023), and was conducted according to the ethical standards established by the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Written informed consent was obtained, which included authorization to publish the data in a pseudo-anonymised form in an open data repository.

Measurement Protocol

First, the Instrument Response Function (IRF) of the system was acquired by connecting the injection and collection fibers together with a thin layer of diffuser between them. This thin layer of diffuser (common teflon tape) is necessary to fill the full numerical aperture of the collection fiber which otherwise would remain under-filled, in contrast to what happens during a measurement: in fact, the scattering of the sample increases the emission angles of photons. The injection and collection fibers were inserted into a 3D-printed hand-held (by the subject) probe with 2 cm interfiber distance, and was placed on the body part of interest. The spectral range spanned from 610 nm to 1110 nm in steps of 10 nm and the acquisition time per wavelength was set to 1 s. We first performed three consecutive spectral scans. These scans are saved in a single custom binary .DAT file (Python and Matlab conversion tools provided). Then, the probe was removed and re-positioned on the same body part, and the operation was repeated once again to account for probe repositioning. No talking was allowed during the measurements, room lights were switched off, and no special measures were used to shield the probe from residual ambient light. Body parts investigated are the upper arm (on the muscle), the radius-ulna area (on the superficial bone structure of the radius and ulna), the abdomen, the forehead, and the calcaneus. The choice of measurement positions was determined based on the idea to measure locations with different chromophore composition such as water (muscle), lipid (fat), collagen (bone) and to compare with standard measurements in the TD-DOS field (forehead). For the measurements on the abdomen, the subjects were lying down on a bed, whereas they remained in a seated position for the rest of the measurements. Then, a standard ultrasound (US) portable system (E2 Exp., Sonoscape Medical Corp., China) was used, with a linear US probe to acquire the US images.

DTOFs Analysis

Light propagation in diffusive or scattering media is described by the RTE, which models the rate of variation of the radiance \(I(\overrightarrow{r},\overrightarrow{s},t)\) due to absorption and scattering processes:

where v is the speed of light in the medium, μa and μs are the absorption and scattering coefficients, \(p(\overrightarrow{s},\overrightarrow{{s}^{{\prime} }})\) is the scattering phase function and \(Q(\overrightarrow{r},\overrightarrow{s},t)\) represents the source term.

For highly diffusive media, where many scattering events occur before a photon can get absorbed, we can approximate the radiance with an isotropic term corrected by a small non-isotropic contribution:

where \(\overrightarrow{J}\) is a small directional flux. For particular geometries and under the diffusion approximation, the RTE can be analytically solved. For a semi-infinite homogeneous medium, the analytical solution of the fluence for a delta source in time and space and under Partial Current Boundary Conditions is a Green’s function:34

where ρ is the radial distance from the source, z is the distance normal to the boundary, \({z}_{s}={({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} })}^{-1}\), \(D=1/[3({\mu }_{a}+{\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} })]\) is the diffusion constant, and \({z}_{e}=2AD\), with A depending on the mismatch at the boundary of the refractive index of the medium. The expression for the reflectance DTOFs, our physical observable, can be recovered as:

For our analysis, we used the above described solution of the diffusion equation in the hypothesis of a homogenous semi-infinite model, where we employed the partial current boundary conditions with an assumption of 1.45 for the refractive index for our medium. A theoretical DTOF under these conditions, with initial guess values for the μa and \({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\) was simulated and was convolved with experimental IRF. We then used a nonlinear Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm to fit this curve to the experimental DTOF by modifying the μa and \({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\), and thus find the absorption and scattering coefficients of the sample. For the fitting procedure, we exploited only a portion of the curve to avoid noise and fitting artifacts: we considered from the 80% on the peak on the rising edge of the DTOF to the 3% on the falling edge. We also performed a background subtraction before data analysis. In Fig. 3 we report as an example the experimental DTOF in black, the IRF in red, and the fitted curve in yellow. The initial guess for the absorption and reduced scattering parameters was 0.1 cm−1 and 10 cm−1, respectively.

It is worth underlining that, instead of the scattering coefficient, the reduced scattering coefficient was used for all calculations, defined as:

with \(g= < \cos \,(\theta ) > =2\pi {\int }_{0}^{\pi }\cos \,(\theta )p(\theta )\sin \,(\theta )d\theta \) being the anisotropy coefficient, i.e. the average cosine of the scattering angle.

Data Representation

By plotting the absorption and reduced scattering coefficients retrieved as a function of the selected input wavelength, we build the spectra of the optical properties of a tissue as shown in Fig. 1.

Data Records

Data Management Plan

The dataset is available with open access on Zenodo at the following reference32. It follows an organised structure as shown in Fig. 4, based on a general template we adopted to streamline the publication of highly structured data in open repositories, and which is detailed below. All of our datasets (including this one) are arranged in four numbered folders, namely:

-

1.

OVERVIEW: A folder which acts as a guide to the dataset containing the link to the published paper (if any), general information on the dataset in a ReadMe.PDF file, and a commented index of the content (in .json format);

-

2.

DATA: It groups all the relevant data acquired during the experiment and is divided into subfolders. The RAW DATA folder contains all the raw data in different formats, while the META DATA contains the relevant metadata, subdivided in a structured description of the experimental conditions (.json file) and in a set of tables (.csv files) that act as lookup tables for the experiments and make it easy to programmatically upload the information in any database/analysis software. Finally, it could also include PRE-PROCESSED DATA, in case a standardly used manipulation (such as background subtraction) of the immutable raw data is needed for the analysis.

-

3.

TOOLS: This folder contains relevant codes (written in Python and/or Matlab) to open proprietary or non-standard raw data formats, with an example of test data; or for data analysis and visualization, along with a description of analysis methods and relevant manuals. These are then divided into ‘Data Reading’ and ‘Data Analysis’ tools appropriately.

-

4.

RESULTS: This folder contains the final processed output in case of a publication, or could even contain the various versions of analysis in case of an ongoing project.

This scheme is quite versatile and well adapts to different types of measurements, experiments, and simulations. In our opinion, its main advantage resides in the fact that, simply by following the structure shown in Fig. 4, data are automatically generated as structured and are readable from the very beginning of the experiment. It is worth highlighting the distinction between (raw) DATA and RESULTS: while raw data is immutable and objective, reflecting the chosen experimental conditions, results are dynamic and can evolve and adapt across different versions, either to suit a user’s specific application or in response to new analytical methods

Data Description

The formats and content of the data vary depending on the folder where they are located. The OVERVIEW folder contains descriptive information in either .PDF or .JSON formats. On the other hand, the RAW DATA contains the DTOFs that are acquired by a home-built acquisition software and are stored in a binary encoded .DAT format. Each ‘.DAT’ file begins with a header of 764 characters and a sub-header of 204 characters, both of which provide information on the measurements such as the number of wavelengths (51), the number of temporal channels (4096), and the binning size (3 ps/bin). The file then contains the 4096 short integers representing the photon counts in each channel. The histogram of these values yields a DTOF. The different DTOFs pertaining to consequent wavelengths and repetitions are then encoded in a similar way, with the aformentioned subheader functioning as a separator. The ‘Data Reading’ folder in TOOLS contains a MATLAB and a Python code to help decode these binary data and store the DTOFs in matrices or arrays. The META DATA contains a Table.csv file that provides information to cross-reference the SUBJECT ID, location and repositioning measurements with the particular .DAT file. It also contains a Info .JSON file containing general information about the experimental system and measurement protocol. Data are then analyzed by a second, proprietary, home-built software (not included) and the output files are plain ‘.txt’. Data plotting is achieved through a simple sorting of the output data to select the relevant data using a pivot table either in a spreadsheet or python, and an example is provided in the form of a excel sheet with the pivot tables.

In Fig. 5 we report the complete dataset for the absorption coefficient, where columns cycle over body parts while the rows cycle over the subjects. Figure 6 on the other hand depicts the corresponding reduced scattering spectra in the above mentioned format. The ultrasound images related to the 10 different subjects and the 5 body locations are reported in Fig. 7. These data are saved as images in ‘.jpg’ format. As stated in Section: Background and Summary, all data presented here are uploaded in Zenodo32.

Absorption spectra catalogued according to subjects (rows) and part of the body investigated (columns). Red and blue curves are the two repetitions of the measurements, after repositioning the probe. The shaded regions display the standard deviation for each of the re-positioning measurements, across the three spectral repetitions.

Reduced scattering spectra catalogued according to subjects (rows) and part of the body investigated (rows). Red and blue curves are the two repetitions of the measurements, after repositioning the probe. The shaded regions display the standard deviation for each of the re-positioning measurements, across the three spectral repetitions.

Technical Validation

System Validation

Throughout the years, the system validation was performed following established international protocols for performance assessments of diffuse optics instruments. Namely, we followed the BIP (basic instrument performance) protocol for assessing the basic hardware performances35, the MEDPHOT protocol for characterisation of homogeneous diffusive media36, and the NEUROPT protocol for probing heterogeneous tissues37. The system used in this paper was also engaged in the BITMAP exercise, where the 3 mentioned protocols were applied to test a total of 28 instruments in 12 institutions involving 53 researchers, and the cumulative and specific results for the exercise, as well as the definition and implementation of the specific tests can be found in the BITMAP paper38, where the system used in the present study is identified by the code #25. The exercise was performed using the very same kit of diffuse optical phantoms circulated in a round-robin scheme around the different laboratories.

Table 2 reports the final synthetic indicators for our system compared to the mean value and standard deviation for the instruments involved in the BITMAP exercise. The table reports the synthetic indicators (FOM = Figure of Merit) related to 10 different tests belonging to the 3 protocols (not all the tests are included). In most of the tests, the FOM is related to μa or \({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\) separately (column Opt). Count indicates the number of instruments for which the test was applicable. It is necessary to note that the instruments involved in the exercise are different both in terms of technique (time-domain, frequency-domain, continuous-wave) and application (spectroscopy, oximetry, mammography, blood flow, imaging), and therefore are optimised towards a specific subsets of parameters. Our system is a time-domain spectrometer, and therefore aims at accurate retrieval of the absorption and scattering spectra rather then – for instance – at detection of buried inhomogeneities as in the case of optical mammographs.

Going into detail of specific FOMs, the FWHM of the IRF is 124 ps which compares well with an average of 293 ps. This is required for a spectroscopy system aiming at coping with high μa in biological tissues around the water absorption peak ~970–975 nm at body temperature. The Responsivity is rather poor (about 2 orders of magnitude lower than the mean) as a consequence of the optimisation of the temporal response and reduction of noise (dark counts), at the expense of overall light harvesting. The assessment of the accuracy in the retrieval of optical properties is rather subtle, since so far there is no accepted reference standard for bulky diffusive media. Table 2 reports only the discrepancy with respect to the median among all instruments, which is a poor substitute for the conventional true value. The Linearity with respect to μa and \({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\) in the 0–0.4 and 3–15 cm−1, respectively, is very good as well as the absorption-to-scattering and scattering-to-absorption uncoupling. To reach 1% precision (standard deviation) on a single-site acquisition, around 320–590 kilo counts per second (kcps) are needed, well achieved in current in-vivo measurements at most wavelengths. The temporal stability is optimal, with negligible Drift (<0.1%, tested for 10 hours of consecutive measurement) and a minimal Range of fluctuation over 1 h (<0.1%). Finally, the Reproducibility is better then 2% for measurements repeated over 3 different days. The final two FOMs – CNR and Contrast – are rather poor. Yet these indicators are relevant for imagers aiming to detect deep buried inhomogeneities, which is not the scope of the present study. All these figures are reported in the BITMAP campaign38 at 830 nm, where a significant number of instruments were available. For broadband spectral measurements, no discrepancy data can be reported since only two systems covered a wide spectral range. Conversely, it is possible to extract over the whole 600-1100 nm range the Noise (μa: mean 1.4%, max 3.1%; \({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\): mean 1.1%, max 2.9%, for 500,000 counts) and the Reproducibility values (μa: mean 1.2%, max 4.9%; \({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\): mean 0.9%, max 2.2%).

To cope with the lack of reference standards with solid phantoms for the estimation of the accuracy, as discussed above, we validated the system using liquid phantoms made of commercial Intralipid and water, where a general consensus is now established39. Figure 8 shows the absorption and reduced scattering spectra obtained on a 5.54% dilution of Intralipid 20% in water (dashed line), overlapped to the reference spectra (solid lines) derived from literature.39 Data were acquired in reflectance geometry, with an interfiber distance of 2 cm. For the absorption spectrum (Figure 8a) there is a good agreement with published data40, with a discrepancy below 700 nm where the absorption is lower than 0.01 cm−1. This discrepancy is possibly due to the residual absorption of the solid fraction of Intralipid or by the failure of the semi-infinite medium approximation for such low μa values, which can be due to the loss of photons at the boundary of the phantom container (black in colour). Note that this occurrence is never encountered in biological tissues. The scattering spectrum (Figure 8b) was compared with the Mie-derived power law41\({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }(\lambda )=a{(\lambda /{\lambda }_{0})}^{-b}\) interpolated over the data presented in the multi-laboratory exercise for Intralipid characterization42, leading to a = 28.10 cm−1 and b = −1.245, using λ0 = 600 nm. Overall, there is a good agreement in the spectral trend, with an overestimation of around 1 cm−1, possibly ascribed to the diffusion model43, as observed elsewhere, and a bump around 980 nm due to the failure of the diffusion approximation caused by the high water absorption. This scattering-to-absorption coupling effect is well documented and is visible also in the in-vivo spectra.44

Qualitative Spectra Description

Figures 5 and 6 show the absorption and reduced scattering spectra of the 10 subjects across 5 body locations. The blue and red curves differentiate between the average values of the measurements performed with different probe positioning, while the shaded regions depict the standard deviation (SD) across the 3 repetitions at the same position. As evidenced by the data, there exists a lot of variability across the subjects and across the body locations, giving us insights into the various chromophores in play. For example, comparing between Subject 1 and 2 from Table 1, we notice that the former has a BMI of 18, while the latter has 24.7, and hence we expect Subject 2 to have a higher lipid content. This is noticeable in the μa spectra on the abdomen. Since we are measuring at ρ = 2 cm, with 500 kcps, we detect photons from the upper layers which contain more lipids in the case of a person with a higher BMI, which is the case of Subject 2. We observe a higher conspicuous peak at the lipid absorption peak of 920 nm for subject 2, whereas for Subject 1, the absorption is dominated by that of the water peak at 980 nm. Subject 3 on the other hand has a similar BMI to Subject 2 and hence also have similar spectra. This can also be verified using the ultrasound images. It is possible to similarly cross-reference the spectra of other subjects with the US images and their demographic information.

Figure 9 summarises this variability between the subjects. The solid lines in the first row represents the mean absorption while the shaded regions are the standard deviation (SD) across the subjects. The change in the shape of the spectra immediately appears evident. Examining the spectra with the region beyond 700 nm, we notice the upper arm is characterized by the highest absorption on an average and this is due to the higher concentration of muscles for on this location, leading to a higher water absorption. Similarly, the radius-ulna, the calcaneus and the forehead show a major contribution from the water absorption as expected, with a shoulder peak at 920 nm arising due to lipid absorption. However, the average spectra of the radius-ulna and the calcaneus share more similarities in shape and values than the others due the fact that we are also measuring the bone at these sites. Indeed, this can be observed from a subtle shoulder on the peak around 1030 nm, which we believe could be due the collagen in the bone. The forehead, as expected, shows only a strong water absorption and no peak due to lipids since humans do not store fat there, while the abdomen shows the peak of the lipids to be the major component rather than water. The region below 700 nm gives us insights into the hemoglobin absorption. While the upper arm and the radius-ulna region are rich with blood vessels and have a high absorption in this region, the abdomen region we are probing does not, similarly to the calcaneus. The SD further gives us valuable information on the variability between subjects. The highest SD among subjects is on the abdomen and the upper arm, as the composition of fat-to-muscle ratio in these regions is affected by BMI and fitness level among other factors, and can vary greatly. The forehead on the other hand has the least SD as it is not affected by these factors. The calcaneus and the radius-ulna have SD ranges in between, accordingly.

Variability in the optical properties across the subjects at the different measured locations. The solid lines in the top two rows depict the mean absorption and scattering spectra respectively across all the subjects, while the shaded region represents the standard deviation (SD) across means for individual subjects. The bottom row compares intra-subject versus inter-subject variability. The red lines stand for the coefficient of variation (CV) across measurements per site on a single subject, whereas the black lines show the CV across all the subjects. In both the cases, the solid lines represent the CV for absorption while the dotted ones correspond to scattering.

The scattering in the middle row follows similar trends with regards to the SD. The forehead has the least variability while the abdomen has the highest, due to the different layers underneath the skin that are made of varying microstructure. The bottom row instead displays the intra-subject versus inter-subject variability. All the lines measure the coefficient of variation (CV). The CV among the different subjects at the same location is much higher that the CV within the measurements on a single subject. This difference in CV again depends on body location with the abdomen showing the highest, and in general is much lower for scattering as it is not dependent on the chemical composition.

However, it is worth noting that there do exist certain discrepancies to be addressed too. The probe repositioning indeed makes a difference for some of the absorption spectra, especially on the upper arm, the radius-ulna and the calcaneus. This is consistence with the fact that the abdomen and the forehead, while still multilayered, are less sensitive to the probe positioning, whereas the others have variation due the muscle or bone presence. Further, the coupling at the water absorption peak adds uncertainty to the μa and \({\mu }_{s}^{{\prime} }\) and can be corrected using the Mie theory to smoothen the scattering. While BMI can be a useful parameter to understand inter-subject variation, it is to not be taken at face value as it is not a direct indicator of presence of lipids and the US images should also be considered. The age of the subjects could also be another factor in general. However, in this study, since 80% of the subjects fall in the same age group, it was not found to add any new information, and has been left out for anonymity purposes. In general, the age, BMI and the fitness levels of the subjects need to be kept in mind while considering the mean spectra in Fig. 9.

Usage Notes

The general outline and content of the folders uploaded to Zenodo have already been discussed previously. To visualize a particular data, e.g. - ‘The DTOF at λ = 800 nm for Subject 1, obtained from the measurement on the Abdomen’ the user needs to load the file ‘Table InVivo.CSV’ from the META DATA subfolder, use the relevant filters (Subject 1, Abdomen) to retrieve the appropriate .DAT file names (two re-position repetitions) and their corresponding IRF files. Then, by using the ‘Data reading’ codes in the ‘TOOLS’ on the filename, the user will obtain from the .DAT file, a matrix containing the DTOF number in the rows and the counts in each of the 4096 channels in the columns. Each row can be then be converted into a histogram to obtain a DTOF, and depending on the initial λ and the step-size, one can obtain the DTOF at 800 nm as the 19th DTOF.

This study involves research on human volunteer subjects, who are identified with unique codes. Data usage is free, but personal data and all information not included in this paper (included identities) will not be provided. The dataset is uploaded with a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, permitting the reuse of the data provided proper attribution is given.

Data availability

The complete dataset32 with the raw data, the metadata, the tools for reading and visualization, along with the final results, as described in the article, is available with open access on ZENODO at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15828014.

Code availability

The code to decode the raw data from .DAT files into matrix arrays and visualize the data is provided in the ‘Tools: Data reading’ folder of the dataset32. The tools and methods to analyze the DTOFs is provided in the DTOFs analysis section, with a brief description of the analysis process also given in the ‘Tools: Data analysis’ folder of the dataset.

References

Sherafati, A. et al. A high-density diffuse optical tomography dataset of naturalistic viewing. Scientific Data 12, 1762 (2025).

von Lühmann, A., Li, X., Gilmore, N., Boas, D. A. & Yücel, M. A. Open access multimodal fnirs resting state dataset with and without synthetic hemodynamic responses. Frontiers in Neuroscience 14, 579353 (2020).

Currà, A. et al. A dataset of visible–short wave infrared reflectance spectra collected in–vivo on the dorsal and ventral aspect of arms. Data in Brief 33, 106480 (2020).

Li, C. L. et al. Extended-wavelength diffuse reflectance spectroscopy dataset of animal tissues for bone-related biomedical applications. Scientific Data 11, 136 (2024).

Ayala, L. et al. The spectral perfusion arm clamping dataset (spectralpaca) for video-rate functional imaging of the skin. Scientific Data 11, 536 (2024).

Elsen, T. et al. A dataset of optical spectra and clinical features acquired on human healthy skin and on skin carcinomas. Data in Brief 53, 110163 (2024).

Martín-Pérez, A. et al. Slimbrain database: A multimodal image database of in vivo human brains for tumour detection. Scientific Data 12, 836 (2025).

Nitrc: fnirs data repository. https://www.nitrc.org/frs/?group_id=1071. Accessed: 2025-02-14.

Openfnirs: Open functional near-infrared spectroscopy resource hub. https://openfnirs.org/. Accessed: 2025-02-14.

Openneuro: Open access neuroimaging data repository. https://openneuro.org/. Accessed: 2025-02-14.

Mule, N. et al. Monitoring of neoadjuvant chemotherapy through time domain diffuse optics: Breast tissue composition changes and collagen discriminative potential. Data set, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11047706 (2024).

Serra, N. et al. In vivo optimization of the experimental conditions for the non-invasive optical assessment of breast density. Data set, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10955509 (2024).

Damagatla, V. Dataset: Use of bioresorbable fibers for short-wave infrared spectroscopy using time-domain diffuse optics. Data set, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12667650 (2024).

Bossi, A., Bianchi, L., Saccomandi, P. & Pifferi, A. Dataset of “optical signatures of thermal damage on ex-vivo brain, lung and heart tissues using time-domain diffuse optical spectroscopy”. Data set, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10685455In Biomedical Optics Express 15(4), 2481–2497 (2024).

Bassani, M., Martelli, F., Zaccanti, G. & Contini, D. Independence of the diffusion coefficient from absorption: experimental and numerical evidence. Opt. Lett. 22, 853–855, https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.22.000853 (1997).

Pifferi, A. et al. New frontiers in time-domain diffuse optics, a review. Journal of Biomedical Optics 21, 091310, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.21.9.091310 (2016).

Yaroslavsky, I. V., Yaroslavsky, A. N., Tuchin, V. V. & Schwarzmaier, H.-J. Effect of the scattering delay on time-dependent photon migration in turbid media. Appl. Opt. 36, 6529–6538, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.36.006529 (1997).

Taroni, P., Comelli, D., Pifferi, A., Torricelli, A. & Cubeddu, R. Absorption of collagen: effects on the estimate of breast composition and related diagnostic implications. Journal of Biomedical Optics 12, 014021, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.2699170 (2007).

Taroni, P. Diffuse optical imaging and spectroscopy of the breast: A brief outline of history and perspectives. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 11, 241–250, https://doi.org/10.1039/C1PP05230F (2012).

Üncü, Y. A. et al. Differentiation of tumoral and non-tumoral breast lesions using back reflection diffuse optical tomography: A pilot clinical study. International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology 31, 2023–2031 (2021).

Mule, N. et al. Monitoring of neoadjuvant chemotherapy through time domain diffuse optics: breast tissue composition changes and collagen discriminative potential. Biomedical Optics Express 15, 4842–4858 (2024).

Kacprzak, M. et al. Application of a time-resolved optical brain imager for monitoring cerebral oxygenation during carotid surgery. Journal of Biomedical Optics 17, 016002, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.17.1.016002 (2012).

Lacerenza, M. et al. Challenging the skin pigmentation bias in tissue oximetry via time-domain near-infrared spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 16, 690–708 (2025).

Doornbos, R. M. P., Lang, R., Aalders, M. C., Cross, F. W. & Sterenborg, H. J. C. M. The determination of in vivo human tissue optical properties and absolute chromophore concentrations using spatially resolved steady-state diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Physics in Medicine & Biology 44, 967, https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/44/4/012 (1999).

Lanka, P. et al. Non-invasive investigation of adipose tissue by time domain diffuse optical spectroscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 11, 2779–2793, https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.391028 (2020).

Kim, J. A., Wales, D. J. & Yang, G.-Z. Optical spectroscopy for in vivo medical diagnosis-a review of the state of the art and future perspectives. Progress in Biomedical Engineering 2, 042001, https://doi.org/10.1088/2516-1091/abaaa3 (2020).

Pifferi, A. et al. Initial non-invasive in vivo sensing of the lung using time domain diffuse optics. Scientific Reports 14, 6343 (2024).

Serra, N. et al. In vivo optimization of the experimental conditions for the non-invasive optical assessment of breast density. Scientific Reports 14, 19154 (2024).

Kothuri, S. K. et al. Broadband time domain diffuse optical characterization of human cadaver bone from 500 to 1100 nm. Scientific Reports 15, 25931 (2025).

Correia, J. H., Rodrigues, J. A., Pimenta, S., Dong, T. & Yang, Z. Photodynamic therapy review: Principles, photosensitizers, applications, and future directions. Pharmaceutics 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13091332 (2021).

Bossi, A., Bianchi, L., Saccomandi, P. & Pifferi, A. Optical signatures of thermal damage on ex-vivo brain, lung and heart tissues using time-domain diffuse optical spectroscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 15, 2481–2497 (2024).

Bargigia, I. et al. Dataset for in-vivo absorption and reduced scattering spectra across five body locations on ten subjects using time-domain diffuse optics, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15828014 (2025).

Martinenghi, E. et al. Time-resolved single-photon detection module based on silicon photomultiplier: A novel building block for time-correlated measurement systems. Review of Scientific Instruments 87 (2016).

Martelli, F., Del Bianco, S., Ismaelli, A. & Zaccanti, G. Light Propagation through Biological Tissue and Other Diffusive Media: Theory, Solutions, and Validation. SPIE Press, Bellingham, WA (2022). https://doi.org/10.1117/3.2624517 (2022).

Wabnitz, H. et al. Performance assessment of time-domain optical brain imagers, part 1: basic instrumental performance protocol. Journal of Biomedical Optics 19, 086010, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.19.8.086010 (2014).

Pifferi, A. et al. Performance assessment of photon migration instruments: the medphot protocol. Appl. Opt. 44, 2104–2114, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.44.002104 (2005).

Wabnitz, H. et al. Performance assessment of time-domain optical brain imagers, part 2: nEUROPt protocol. Journal of Biomedical Optics 19, 086012, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.19.8.086012 (2014).

Lanka, P. et al. Multi-laboratory performance assessment of diffuse optics instruments: the BitMap exercise. Journal of Biomedical Optics 27, 074716, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.27.7.074716 (2022).

Spinelli, L. et al. Determination of reference values for optical properties of liquid phantoms based on intralipid and india ink. Biomed. Opt. Express 5, 2037–2053, https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.5.002037 (2014).

Kou, L., Labrie, D. & Chylek, P. Refractive indices of water and ice in the 0.65- to 2.5-μm spectral range. Appl. Opt. 32, 3531–3540, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.32.003531 (1993).

Mourant, J. R., Fuselier, T., Boyer, J., Johnson, T. M. & Bigio, I. J. Predictions and measurements of scattering and absorption over broadwavelength ranges in tissue phantoms. Appl. Opt. 36, 949–957, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.36.000949 (1997).

Spinelli, L. et al. Inter-laboratory comparison of optical properties performed on intralipid and india ink. In Biomedical Optics and 3-D Imaging, BW1A.6, https://doi.org/10.1364/BIOMED.2012.BW1A.6 (Optica Publishing Group, 2012).

Bargigia, I. et al. Time-resolved diffuse optical spectroscopy up to 1700 nm by means of a time-gated ingaas/inp single-photon avalanche diode. Appl. Spectrosc. 66, 944–950 (2012).

Farina, A., Bargigia, I., Taroni, P. & Pifferi, A. Note: Comparison between a prism-based and an acousto-optic tunable filter-based spectrometer for diffusive media. Review of Scientific Instruments 84, 016109, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4789312 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial and infrastructural support by - (i) European Union’s NextGenerationEU Programme with the I-PHOQS Infrastructure [IR0000016, ID D2B8D520, CUP B53C22001750006] “Integrated infrastructure initiative in Photonic and Quantum Sciences”. - (ii) European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme: PHAST-ETN project under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie; grant agreement No. 860185

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P. and P.T. conceived and planned the experiments. S.K., V.D., A.B., and A.P. carried out the experiments. S.K. and I.B. analyzed the data. I.B., A.P. and V.D. took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Damagatla, V., Karremans, S., Bossi, A. et al. In-vivo optical properties spectra across five body locations on ten subjects using time-domain diffuse optics. Sci Data 13, 261 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-026-06586-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-026-06586-9