Abstract

Changes in the stability, hydrogen diffusion, and mechanical properties of the NbH phases from Ni-doping was studied by using first-principles methods. The calculation results reveal that the single H atom adsorption is energetically favorable at the tetrahedral interstitial site (TIS) and octahedral interstitial site (OIS). The preferred path of H diffusion is TIS-to-TIS, followed by TIS-to-OIS in both Nb16H and Nb15NiH. Ni-doping in the Nb15NiH alloy lowers the energy barrier of H diffusion, enhances the H-diffusion coefficient (D) and mechanical properties of the Nb16H phase. The value of D increases with increasing temperature, and this trend due to Ni doping clearly becomes weaker at higher temperatures. At the typical operating temperature of 400 K, the D value of Nb15NiH (TIS) is about 1.90 × 10−8 m2/s, which is about 80 times higher than that of Nb16H (TIS) (2.15 × 10−10 m2/s). Our calculations indicated that Ni-doping can greatly improve the diffusion of H in Nb.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Membrane reactors, used for the separation and purification of dense hydrogen, are one of the most important components in industrial hydrogen production by the steam reforming of natural gas1, 2. Currently, although Pd and its alloys have been widely used for hydrogen separation and purification, their disadvantages such as high price and scarcity are also obvious. Over the last few decades, researchers have gradually shifted their attention to group VB transitional metals (V, Nb, and Ta) due to their potential of hydrogen permeability and relatively lower price3. Among them, niobium (Nb) has been well regarded as one of the most promising hydrogen separation materials, since Peterson et al. reported that it possesses excellent high-temperature mechanical properties as well as corrosion resistance4,5,6. Furthermore, Nb and its alloys also have been extensively used in hydrogen-related high-temperature structural applications, such as the diverter and nuclear material at the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), due to their strong resistance to corrosion, high melting point, excellent mechanical properties, and small cross section of neutron absorption4,5,6,7,8. However, Nb alloys often have poor resistance to hydrogen embrittlement and therefore are limited in their practical applications9,10,11,12.

Further exploring Nb-based alloys with other elements is one solution to the above problem. Watanabe et al. revealed that the addition of W and Ru decreases the hydrogen solubility in Nb and therefore improves its resistance to hydrogen embrittlement9, 11. Hu et al. reported that the addition of W can improve the mechanical properties of the Nb16H phase, decrease the structural stability of the Nb15WH (TIS) phase, lower the diffusion barrier of H, and enhance diffusion paths for H13, 14. In addition, Ni is an effective catalytic component and widely used in metal-based alloy compounds for hydrogen storage. Doping with Ni can decrease the sensitivity to impurity gas on the surface, thereby reducing the pollution caused by impurities. To the best of our knowledge, however, the fundamental work of Nb alloying with Ni has not been reported in the literature. It is necessary to study the structural and diffusion properties of Ni in the NbH phase by theoretical methods. Such calculations will contribute to the in-depth study of new Ni-based hydrogen permeation materials.

In this paper, we employ highly accurate first-principles method to investigate the effects of Ni doping on the structural stability, electronic structure, mechanical property, and H-diffusion behavior of the Nb16H phase. To compare with the experimental composition of 5 at% of Ni in Nb16H15,16,17, we purposively selected the composition of Nb16H in this work, and one Ni atom is added to Nb16H. Our calculated results revealed that the addition of Ni can greatly improve the diffusion properties of H and the mechanical property of Nb. At the same time, our results also provide a theoretical basis for further work on Nb-Ni-based alloys.

Results and Discussion

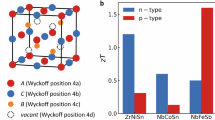

In order to compare to the experimental results15,16,17, a 2 × 2 × 2 super cell containing 16 Nb atoms was built, and one of the Nb atoms was substituted by Ni. To study the diffusion behavior of H atom between the nearest sites, one H atom was placed at the tetrahedral interstitial site (TIS) and octahedral interstitial site (OIS) of Nb and Nb15Ni, respectively. In Nb15NiH (TIS), the Nb-H and Ni-H bond lengths are about 1.96 and 1.65 Å, respectively. After the doping of Ni atoms, the structure was changed from bcc to simple cubic due to the smaller atomic radius of Ni compared to Nb. However, the structure remained as the cubic type. As a typical example, Fig. 1(a) shows the schematic illustrations of Nb15NiH with H atom in TIS and OIS. For clarity, the corresponding atomic configurations of TIS and OIS are displayed in Fig. 1(b) and (c).

Structural stability of Nb16H and Nb15NiH

To examine the effect of Ni-doping on the structural stability of Nb16H and Nb15NiH, the solution energy (E s) of interstitial H atom in Nb16H and Nb15NiH was investigated by means of the following formula:

where \(E{{\rm{Nb}}}_{{\rm{16}}-{\rm{x}}}{{\rm{Ni}}}_{{\rm{x}}}{\rm{H}}\), \(E{{\rm{Nb}}}_{{\rm{16}}-{\rm{x}}}{{\rm{Ni}}}_{{\rm{x}}}\) and \(E{{\rm{H}}}_{{\rm{2}}}\) are the total energies obtained from first principles calculations. The calculated E s values of H-TIS and H-OIS in Nb and Nb15Ni are summarized in Table 1. The TIS and OIS models of Nb16H and Nb15NiH are all thermodynamically stable with negative solution energy. Moreover, the E s of Nb16H (TIS) is obviously lower than that of Nb16H (OIS), which indicates that TIS is more energetically favorable than OIS for H in the bcc Nb. However, it must be pointed out that the E s of TIS and OIS models in Nb15NiH alloys are very close to each other. It suggests that Ni-doping will increase the number of stable positions for H atom in the Nb16H phase.

Energy barrier of H diffusion in Nb16H and Nb15NiH

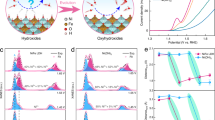

To investigate the effect of Ni-doping on H diffusion behavior, the climbing image nudged elastic band method (CI-NEB) is used to find out the minimum energy path and energy barrier for the H diffusion in Nb16H and Nb15NiH18,19,20,21. As shown in Figs 2 and 3, the possible paths of H diffusion in both samples are TIS → TIS and TIS → OIS. The energy barrier from TIS to TIS in Nb is 0.22 eV, which is lower than the corresponding value of 0.36 eV (at the saddle point) from TIS to OIS, suggesting that the diffusion path of H in bulk Nb should be mainly TIS → TIS rather than TIS → OIS. However, for H diffusion in Nb15Ni, a different trend is observed: the energy barriers of TIS → TIS and TIS → OIS are very close (0.0083 and 0.0054 eV, respectively). This indicates the preferred paths of H diffusion increase from single TIS → TIS to dual TIS → TIS and TIS → OIS. Namely, the additional diffusion paths and lower energy barrier will fundamentally lead to a higher H diffusion coefficient in Nb15NiH alloy. Therefore, the Ni-doping should have an important effect on the diffusion behavior of H in Nb.

Diffusion properties of H in Nb16H and Nb15NiH

The diffusion coefficient (D) is an important parameter for determining the diffusion velocity of H in Nb and Nb15Ni, providing quantitative information about the H diffusion22, 23. According to the Arrhenius diffusion equation, D can be expressed by

where D 0, E a, k, and T are the pre-exponential factor, diffusion energy barrier, Boltzmann constant, and absolute temperature, respectively. For a cubic metal, D 0 can be expressed as

where r and ν are the jump distance and vibration frequency, respectively. We can calculate the vibration frequency ν according to Zener and Wert’s theory24, which is approximately expressed by

where m is the mass of the impurity atom. The mass of the H atom is already known (1.67 × 10−27 kg), the jumping distance of the TIS H in Nb and Nb15Ni is \(a/2\sqrt{2}\), and that of the OIS H in Nb and Nb15Ni is a/4. Figure 4 shows the diffusion coefficient of H in Nb and Nb15Ni as a function of reciprocal temperature. The two phases exhibit different hydrogen diffusion behaviors depending on the operating temperature. In the case of Nb16H, the value of D clearly increases with increasing temperature. Meanwhile, our calculation results are consistent with the experimental data reported by Sakamoto and Yukawa25, 26. Note that the diffusion coefficient is greatly increased with the Ni doping, especially at low temperatures. At 400 K, the calculated D of Nb16H (TIS-TIS), Nb15NiH (TIS-TIS), Nb16H (TIS-OIS), and Nb15NiH (TIS-OIS) are 2.14 × 10−10, 1.90 × 10−8, 3.40 × 10−12, and 1.25 × 10−8 m2/s, respectively. Among the four paths, Nb15NiH (TIS-TIS) has the highest D value, which is about 80 times larger than that of the next one, namely Nb16H (TIS-TIS), followed by Nb15NiH (TIS-OIS). Moreover, for the TIS-TIS case, the effect from Ni-doping on D becomes weaker with increasing temperature. While in the TIS-OIS case, the D value of Nb15NiH remains higher in the full range of 400–1500 K.

Mechanical properties of Nb16H and Nb15NiH

Now we examine the effect of Ni-doping on the mechanical properties of Nb hydride. The elastic constants of Nb16H (TIS and OIS) and Nb15NiH (TIS and OIS) are calculated for comparison. This value could be obtained by analyzing the difference in total energy between the original cell and deformed cell under a series of small strains. The obtained elastic constants are then used to calculate the bulk modulus (B) and shear modulus (G) from the Voigt-Reuss-Hill approximations28, 29. The Young’s modulus (E) is determined by means of E = 9BG/(3B + G)29. After a series of calculations, the lattice constants (a), three independent elastic constants (C 11 , C 12 , and C 44 ), and elastic moduli (B, G, and E) of various Nb16H and Nb15NiH phases are obtained (Table 2). The calculated values of pure Nb are also listed and compared with experimental results. The consistency between the calculated and experimental values proved the reliability of our calculation method.

(i) We use the following criteria for mechanical stability: \({C}_{44} > 0,\,\frac{({C}_{11}-{C}_{12})}{2} > 0\), \(B=\frac{({C}_{11}+2{C}_{12})}{3} > 0,\) \({C}_{12} < B < {C}_{11}\) 30. Table 2 presents the computed values of C 11 , C 12 , and C 44 for the materials, showing that they are all mechanically stable. (ii) The shear modulus G represents the resistance to plastic deformation, while the bulk modulus B represents the resistance to fracture31. The Young’s modulus E can characterize the stiffness of a material, with a higher value in the stiffer material. The values of B, G, and E of Nb15NiH (TIS) and Nb15NiH (OIS) alloys are obviously larger than those of Nb16H (TIS) and Nb16H (OIS) phases. (iii) The values of B, G, and E of Nb15NiH (TIS) and Nb15NiH (OIS) alloys are also obviously larger than those of Nb16H (TIS) and Nb16H (OIS) phases. According to the empirical criterion proposed by Pugh32, if the value of B is about 1.75 times larger than G, the material will be ductile, otherwise fragile. The calculated B/G values listed in Table 2 show that all phases are ductile. These results suggest that the Ni-doping could help to improve the mechanical properties of Nb16H phase, and enhance the resistance to hydrogen embrittlement.

Electronic properties of Nb16H and Nb15NiH

The change of electronic properties in Nb16H and Nb15NiH due to Ni-doping was further investigated. Figure 5 shows the calculated total density of states (DOS) of pure Nb15Ni, Nb15NiH (TIS), and Nb15NiH (OIS). The highest DOS peak at about −2 eV is mainly contributed to the Ni-3d states, and it becomes lower with the addition of H. Similar results were obtained for hydrogen in vanadium by Luo and co-authors33. The partial density of states (PDOS) of Nb15NiH (TIS) and Nb15NiH (OIS) show obvious Ni-H and Nb-H hybridization interactions from the Ni-3d, Nb-4d, and H-1s states in the energy region from about −3.7 eV to the Fermi level (E F ). In the cases of Nb15NiH (TIS) and Nb15NiH (OIS), the stronger DOS peaks of Ni-3d states at energies close to E F imply that the Ni-H bond is stronger than Nb-H. These features of electronic structures signify that the Nb15NiH alloy should have stronger chemical bonding than Nb16H, which will result in improved structural stability and stronger mechanical properties.

Figure 6 shows the charge density of Nb and Nb15Ni with H atom at the TIS and OIS sites, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6(a) and (c), the charge density distribution between H and Nb is symmetrical. However, from Fig. 6(b) and (d), the charge density between H and Ni is obviously higher than that between H and Nb after substituting Ni for Nb. This suggests the Ni-H bond is stronger than Nb-H bond, which is also in agreement with the above DOS analysis.

Conclusions

We have investigated the structural stability, mechanical property, and hydrogen diffusion properties of H in pure Nb and Nb15Ni, using first-principles calculations in combination with empirical theory. The results show that Ni-doping can enhance the mechanical properties of Nb16H phase, decrease energy barrier of H diffusion, and improve H diffusivity in the Nb16H phase. The calculated density of states and charge density distribution reveal that the Ni-H chemical bond formed after Ni-doping is stronger than Nb-H in Nb15NiH, and this is directly responsible for the improved mechanical properties in Nb15NiH. The CI-NEB calculations indicate that the single H atom is energetically favorable for adsorption at the tetrahedral interstitial site (TIS) and octahedral interstitial site (OIS) in both Nb16H and Nb15NiH. The preferential path of H diffusion is from TIS-TIS, followed by TIS-OIS. The value of D increases, and the effect on D from Ni-doping clearly weakens at higher temperatures. At low temperatures, the value of D of Nb15NiH (TIS) is about 80 times larger than that of Nb16H (TIS) phase. The current results should help in future experimental investigations of the solubility, diffusion coefficients, and permeability of hydrogen in Nb hydrides.

Computational methods

Our calculations were carried out using the well-known Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)34, 35, in the framework of density functional theory (DFT). The core-electron interactions were described by projected augmented wave (PAW) method36, 37. The exchange-correlations term was approximated by Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) corrected generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functions38. The electronic configurations 4d4s1 and 3d84s2 were treated with the valences of Nb and Ni. The cutoff energy of plane wave was set to 360 eV, and the k-mesh of 5 × 5 × 5 was used in the Brillouin zone, which turns out to be sufficient to obtain convergence to less than 1.0 × 10−6 eV. Then, the atomic coordinates and crystal volume were relaxed with the conjugate gradient method, until the forces acting on all atoms are less than 0.01 eV/Å. These parameters ensured good convergence in the total energy. The migration barriers were calculated using the climbing image nudged elastic band method (CI-NEB)18. The calculation convergence and parameters stay the same for the ground state calculations.

References

Kikuchi, E. Membrane reactor application to hydrogen production. Catal. Today 56, 97–101 (2000).

Shirasaki, Y. et al. Development of membrane reformer system for highly efficient hydrogen production from natural gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 34, 4482–4487 (2009).

Nambu, T. et al. Enhanced hydrogen embrittlement of Pd-coated niobium metal membrane detected by in situ small punch test under hydrogen permeation. J. Alloys Compd. 446, 588–592 (2007).

Liu, Z. H. & Shang, J. X. Elastic properties of Nb-based alloys by using the density functional theory. Chin. Phys. B 21, 016202 (2012).

Khowash, P., Gowtham, S. & Pandey, R. Electronic structure calculations of substitutional and interstitial hydrogen in Nb. Solid State Commun 152, 788–790 (2012).

Peterson, D. T., Hull, A. B. & Loomis, B. A. Hydrogen embrittlement considerations in niobium-base alloys for application in the ITER divertor. J. Nucl. Mater. 191, 430–432 (1991).

Sakamoto, K., Hashizume, K. & Sugisaki, M. Hydrogen concentration dependence of tritium tracer diffusion coefficient in alpha phase of niobium. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 43, 811–815 (2006).

Cheng, Y., Yang, S. H., Lan, M. & Lee, C. H. Observations on the long-lived Mossbauer effects of 93mNb. Sci. Rep 6, 36144 (2016).

Watanabe, N. et al. Alloying effects of Ru and W on the resistance to hydrogen embrittlement and hydrogen permeability of niobium. J. Alloys Compd. 477, 851–854 (2009).

Zhang, G. X. et al. Alloying effects of Ru and W on hydrogen diffusivity during hydrogen permeation through Nb-based hydrogen permeable membranes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35, 1245–1249 (2010).

Yukawa, H. et al. Alloy design of Nb-based hydrogen permeable membrane with strong resistance to hydrogen embrittlement. Mater. Trans. 49, 2202–2207 (2008).

Nambu, T. et al. Enhanced hydrogen embrittlement of Pd-coated niobium metal membrane detected by in situ small punch test under hydrogen permeation. J. Alloys Compd. 446, 588–592 (2007).

Hu, Y. T., Gong, H. & Chen, L. Fundamental effects of W alloying on various properties of NbH phases, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 12745–12749 (2015).

Kong, X. S. et al. First-principles calculations of hydrogen solution and diffusion in tungsten: Temperature and defect-trapping effects. Acta. Mater. 84, 426–435 (2015).

Schober, T. & Wenzl, H. The systems NbH(D), Tall(D), VH(D): structures, phase diagrams, morphologies, methods of preparation. Hydrogen in Metals II. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 29, 11–71 (1978).

Jayalakshmi, S. et al. Characteristics of Ni–Nb-based metallic amorphous alloys for hydrogen-related energy applications. Appl. Energ. 90, 94–99 (2012).

Smith, J. F. The H-Nb (Hydrogen-Niobium) and D-Nb (Deuterium-Niobium) systems. Bull. Alloy. Ph. Diagrams 4, 39–46 (1983).

Henkelman, G. & Uberuaga, B. P. Jonsson H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Wang, J. W. & Gong, H. R. Effect of hydrogen concentration on various properties of gamma TiAl. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39, 1888–1896 (2014).

Wang, J. W., He, Y. H. & Gong, H. R. Various properties of Pd3Ag/TiAl membranes from density functional theory. J. Membr. Sci 475, 406–413 (2015).

Liu, Y. L. et al. Vacancy trapping mechanism for hydrogen bubble formation in metal. Phys. Rev. B 79, 172103 (2009).

Mantina, M. et al. First principles impurity diffusion coefficients. Acta. Mater. 57, 144102–4108 (2009).

Duan, C. et al. First-principles study on dissolution and diffusion properties of hydrogen in molybdenum. J. Nucl. Mater. 404, 109–115 (2010).

Frauenfelder, R. Solution and Diffusion of Hydrogen in Tungsten. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 6, 388–397 (1969).

Sakamoto, K., Hashizume, K. & Sugisaki, M. Hydrogen concentration dependence of tritium tracer diffusion coefficient in alpha phase of niobium. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 43, 811–815 (2006).

Yukawa, H. et al. Analysis of hydrogen diffusion coefficient during hydrogen permeation through niobium and its alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 476, 102–106 (2009).

Lässer, R. & Bickmann, K. Phase diagram of the Nb-T system. J. Nucl. Mater. 132, 244–248 (1985).

Murnaghan, F. D. The compressibility of media under extreme pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 30, 244–227 (1944).

Westbrook, J. H. & Fleischer, R. L. Intermetallic compounds: principles practice. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (1995).

Born, M. & Huang, K. Dynamical theory of crystal lattices. Clarendon press (1954).

Wang, B. T., Li, W. D. & Zhang, P. First-principles calculations of phase transition and elasticity for tizr alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 420, 501–507 (2010).

Pugh, S. F. Relations between the elastic moduli and the plastic properties of polycrystalline pure metals. Philos. Mag. 45, 823–843 (1954).

Luo, J. et al. Dissolution, diffusion and permeation behavior of hydrogen in vanadium: a first-principles investigation. J. Phys-Condense. Mat. 23, 135501–135507 (2011).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab-initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 45, 13244–13249 (1992).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector agmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51471055, 11464008 and 51401060), the Natural Foundations of Guangxi Province (Nos. 2014GXNSFGA118001 and 2016GXNSFGA380001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.M.W. and C.H.H. conceived the study. Y.W. and D.H.W. carried out the numerical calculations. Z.Z.W. and Y.Z. gave some comments. Y.W. wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the analysis and discussion of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, D. et al. Effects of Ni doping on various properties of NbH phases: A first-principles investigation. Sci Rep 7, 6535 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06658-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06658-2

This article is cited by

-

First-Principles Investigation on the Surface Adsorption and Bulk Diffusion of Boron Atom with La-Doped Alpha-Titanium and Beta-Titanium

Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion (2025)

-

Boron Diffusion in Cerium Doped Alpha Titanium and Beta Titanium: First-principles Calculation

Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion (2025)

-

Effect of High Undercooling on Dendritic Morphology and Mechanical Properties of Rapidly Solidified Inconel X750 Alloy

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2020)