Abstract

The quality of CVD-grown graphene is limited by the parallel nucleation of grains from surface impurities which leads to increased grain boundary densities. Currently employed cleaning methods cannot completely remove surface impurities since impurity diffusion from the bulk to the surface occurs during growth. We here introduce a new method to remove impurities not only on the surface but also from the bulk. By employing a solid cap during annealing that acts as a sink for impurities and leads to an enhancement of copper purity throughout the catalyst thickness. The high efficiency of the solid-diffusion-based transport pathway results in a drastic decrease in the surface particle concentration in a relatively short time, as evident in AFM and SIMS characterization of copper foils. Graphene grown on those substrates displays enhanced grain sizes and room-temperature, large-area carrier mobilities in excess of 5000 cm2/Vs which emphasizes the suitability of our approach for future graphene applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene is a two-dimensional carbon material that could revolutionize high-speed electronics and sensors1,2. Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) on copper foil stands as the most promising method for large-scale production of high quality, single layer graphene. Much effort has been invested on bringing CVD graphene quality to the level of pristine mechanically exfoliated sample3. The largest hurdle to this goal is the polycrystallinity of CVD graphene, for the grain boundaries are the main factor of electron scattering in graphene lattice, which affects carrier mobility4.

To limit the parallel growth of grains, the nucleation process has to be controlled. Several reports emphasize the role of surface impurities on the copper substrate in the nucleation of graphene5,6,7. It has been suggested that their curvature results in local supersaturation of carbon in the growth substrate and subsequent precipitation into a graphene seed8,9, and some impurities have lower nucleation barrier than Cu and serve as heteronuclei in early growth10.

Therefore, substantial work has been done to clean and smoothen copper substrate, ranging from annealing, wet etching to mechanical and electrochemical polishing3,5,11,12,13,14,15 with varying degrees of success. While such strategies can remove surface contamination, they cannot remove impurities in the bulk substrate that will precipitate to the surface throughout the growth process. Annealing can improve copper morphology due to the evaporation of impurities. However, the presence of impurities even after 3 hours of annealing6 suggests that the evaporation process is too slow to deplete the impurities close to the surface before new ones can diffuse from the bulk. Moreover, impurities can form refractory oxides or alloy with Cu, which are immune to evaporative removal.

We here introduce a solid-diffusion-based purification process of the copper substrate to overcome these issues. Copper is brought in intimate contact with a solid cap, which allows inter-diffusion at elevated temperatures. Due to the high atomic mass of Cu, it diffuses slower than most of its impurities which results in a purification of the growth substrate.

We show that the purification process results in a significant change in the impurity distribution within the copper foil. The diffusion process was found to control the particle density on the copper foil surface and ultralow particle densities could be obtained. Our model of solid diffusion was validated by a comparison of different cap materials. Graphene grown on these copper foils exhibited enhanced quality as confirmed by spectroscopic and carrier-transport measurements.

Results and Discussion

We first examine the effect of annealing on the copper foil surface without conducting graphene growth. Figure 1 shows AFM pictures of electropolished copper foil before annealing and after 3, 6, 12 hours of annealing. A clear decrease in the particle concentration can be observed. Several mechanisms could be responsible for this change. First, impurities could diffuse into the bulk due to a difference in concentration at the surface16. Furthermore, under elevated temperatures, surface particles of low melting points such as Al will evaporate. Consequently, an increased annealing time helps reduce particle size and numbers. Unfortunately, even after 12 hour annealing surface particles have not completely disappeared. This issue is due to the limited efficiency of the described removal processes. For example, as the concentration of aluminum decreases, the resulting new Cu-Al alloy will exhibit a higher melting point and thus a lower vapour pressure, slowing down the evaporation.

To overcome this issue, we designed a cleaning process that provides an alternative pathway for impurity particles. By placing a material on top of the copper foil, solid diffusion from the copper surface into the cap could occur. This pathway is similar to the gettering method commonly used to remove metal impurities in solar cell-grade silicon17 and occurs for every impurity species that exhibits a non-zero mobility in the cap material. The high atomic weight of Cu will furthermore limit the solid diffusion of the catalyst and result in selective absorption of impurities in the cap.

We indeed observe that the proposed solid-diffusion-based purification method demonstrated a significant improvement in the particle removal (Fig. 2a). Only 3 hours of annealing were needed to reach ultralow particle densities (1 particle/25µm2), which would take normal, uncapped annealing tens of hours to achieve. Fittings of particle densities, obtained from several AFM images for each sample, at different annealing times revealed an exponential decrease whose decay time was 80 times shorter than for uncapped annealing conditions (Fig. 2b).

The observed decrease in particle density is due to the increased efficiency in removing impurities from the bulk since solid diffusion into the cap is expected to be faster than evaporation (Fig. 3a). To prove our model, secondary ion mass spectroscopy (SIMS) measurements were carried out on the copper foil after different pretreatment processes. We have found Al, Si, C impurities in the as-received copper foil. Si and C impurities cannot account for the trend in particle density with annealing that was observed in Fig. 1 since their evaporation will not occur at the process conditions. Aluminum, on the other hand, diffuses readily in Cu18, aggregates at the surface at annealing temperature, and is thus considered a likely candidate for an active impurity.

(a) Schematic of evaporation and solid diffusion pathways; (b) Depth profile of Al in copper foils in non-capped and capped annealing configurations; (c) Enhancement in Al surface concentration proportion compared in non-capped and capped annealed copper; (d) particle density versus the surface portion of Al in copper foils.

We observe a redistribution of Al in the depth profile after annealing compared to the pristine case (Fig. 3b). SIMS depth studies reveal that the proportion of Al in the first 200 nm is increasing for the capped case compared to the evaporation case (Fig. 3b), which confirms that the bulk concentration can be controlled by the efficient removal of impurities from the surface. Our finding is in agreement with a recent study of by Murdock et al.19, where EDX and XPS measurements detected aluminum appearing on copper foil after annealing. Our model of inter-diffusion was further corroborated by evidence of an increased concentration of Al content was found in the quartz cap (see Fig. S1 in Supplementary Information).

Diffusion can be modified by using different cap materials. A material of denser crystal structure, for example, is expected to exhibit a slower inter-diffusion and a lower efficiency in removing impurities. Indeed, diffusion into sapphire with c-plane (001) cut induced less Al on Cu surface (Fig. 3c) and consequently had higher level of remaining bulk contaminants. Surprisingly, the contact area was found to have a small effect on the diffusion flux and caps with higher surface roughness showed similar enrichment effects. We hypothesize that copper’s high ductility at the annealing temperature produces conformal contact to the cap and highlights the robustness of our approach. Finally, we demonstrate the clear correlation between the observed surface enrichment effect and the concentration of particles that remain on the surface after treatment (Fig. 3d).

It should be noted that beside solid diffusion, capping might cause other effects like strain-induced flattening of copper foil, promoting effect or confinement effect. The promoting effect is precluded from this study by using cap made of inert material (quartz) as opposed to Ni20 or graphite13. We have previously shown that the gap between substrate and cap alters the fluid dynamics of graphene growth21, whereas Chen et al.22 attributed the confinement to the enhanced redeposition of evaporated Cu, which leads to reduced roughness. While further study needs to be carried out to isolate individual effects, our opinion is that in the case of this study, all the evidences point to the major influence of decreased impurity. In addition to contributing to the surface roughness, impurities with high carbon solubility like Ni23 or Al24 will be highly likely become graphene nucleation sites.

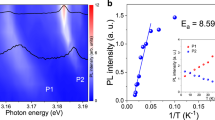

Figure 4, Supplementary Figs S2 and S3 depict benefits of copper’s decreased surface-impurity concentration on the graphene quality. Solid-diffusion cleaned copper foils which have fewer surface particles provide fewer seeds for graphene growth. As a result, under the same growth conditions, they are able to grow graphene domains of larger size and higher coverage ratio compared to traditional methods (Fig. 4a). At the same time, the coverage ratio is also improved (Supplementary Fig. S2), due to the enhanced carbon radical diffusion on the smoother surface25. A decrease of average ID/IG ratio in Raman spectra mapping also confirms the presence of less defects in the capped annealing setup (see Supplementary Fig. S3). Meanwhile, I2D/IG ratio is largely invariant between two methods and characteristic of uniformly monolayer graphene (Supplementary Fig. S4). Reduced grain boundary alleviates electron scattering, giving rise to superior electronic properties. Moreover, the reduction of surface-bound particles can decrease the amount of structural defects in the graphene which was found to have a direct effect on the carrier mobility15. Consequently, graphene mobility of the capped configuration surpassed that of uncapped one by up to 6 times, which is closely correlated to the improved particle density as established in Fig. 4b. The mobility of up to 5400 cm2V−1s−1 measured at room temperature in large scale is among the highest values for CVD graphene grown under low pressure26,27.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated an efficient and fast method to control the concentration of surface-bound particles by diffusion from the Cu foil into a solid cap. This control of the density of nucleation seeds allows graphene synthesis with lower grain density and larger size of single crystalline domains. The resulting graphene films exhibit an enhanced mobility and morphology, which highlights the potential of our approach for high quality graphene growth.

Methods

Copper foil (99.8%, 25 µm, #46365 Alfa Aesar) was electropolished in 85% H3PO4 for 30 minutes to reduce the roughness and remove impurities on the surface13 and then washed in deionized water and dried under a stream of nitrogen. During the annealing process, argon and hydrogen in a 7:2 ratio (350sccm H2, 100sccm Ar) were introduced under atmospheric pressure either with or without various caps. The caps used in the study include c-plane sapphire (Al2O3) (Semiconductor Wafer, Inc.), frosted and polished quartz (XIDE TECHNOLOGY).

Atom force microscopy (Force AFM Genie E7 model) was used to examine copper foil morphology. TOF-SIMS measurement (by a CAMECA IMF 4 f) was carried out using an O2+ beam of 1 keV to sputter the foil and a Ga+ ion beam of 2.5 keV to analyze the secondary ion distribution at the depth up to 1200 nm.

Graphene was grown on the thus treated copper foils with a gas flow of 200 sccm H2 and 10sccm CH4 at a pressure of 10 Torr for 20 minutes at 1020 °C, followed by a cooling down to room temperature similar to our previous study28. Raman measurements were performed in a home-built micro-Raman system using 532 nm laser excitation. FET was fabricated by prepared graphene whence carrier mobility was extracted, with channel length of 250 µm.

References

Liao, L. et al. High-speed graphene transistors with a self-aligned nanowire gate. Nature 467, 305–308 (2010).

Rumyantsev, S., Liu, G., Shur, M. S., Potyrailo, R. A. & Balandin, A. A. Selective gas sensing with a single pristine graphene transistor. Nano letters 12, 2294–2298 (2012).

Hsieh, Y.-P., Chu, Y.-H., Tsai, H.-G. & Hofmann, M. Reducing the graphene grain density in three steps. Nanotechnology 27, 105602 (2016).

Song, H. S. et al. Origin of the relatively low transport mobility of graphene grown through chemical vapor deposition. Scientific Reports 2, 337 (2012).

Han, G. H. et al. Influence of Copper Morphology in Forming Nucleation Seeds for Graphene Growth. Nano letters 11, 4144–4148 (2011).

Wang, H. et al. Controllable synthesis of submillimeter single-crystal monolayer graphene domains on copper foils by suppressing nucleation. Journal of the American Chemical Society 134, 3627–3630 (2012).

Procházka, P. et al. Ultrasmooth metallic foils for growth of high quality graphene by chemical vapor deposition. Nanotechnology 25, 185601 (2014).

Bhaviripudi, S., Jia, X., Dresselhaus, M. S. & Kong, J. Role of kinetic factors in chemical vapor deposition synthesis of uniform large area graphene using copper catalyst. Nano letters 10, 4128–4133 (2010).

Kim, H. et al. Activation energy paths for graphene nucleation and growth on Cu. ACS nano 6, 3614–3623 (2012).

Nie, S., Wofford, J. M., Bartelt, N. C., Dubon, O. D. & McCarty, K. F. Origin of the mosaicity in graphene grown on Cu(111). Physical Review B 84, 155425 (2011).

Lee, J.-K., Park, C.-S. & Kim, H. Sheet resistance variation of graphene grown on annealed and mechanically polished Cu films. RSC Advances 4, 62453–62456 (2014).

Kim, S. M. et al. The effect of copper pre-cleaning on graphene synthesis. Nanotechnology 24, 365602 (2013).

Hsieh, Y. P., Chin, Y. J. & Hofmann, M. Enhancing CVD graphene’s inter-grain connectivity by a graphite promoter. Nanoscale 7, 19403–19407 (2015).

Zhou, H. et al. Chemical vapour deposition growth of large single crystals of monolayer and bilayer graphene. Nature Communications 4, 2096 (2013).

Hofmann, M., Shin, Y. C., Hsieh, Y.-P., Dresselhaus, M. S. & Kong, J. A facile tool for the characterization of two-dimensional materials grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Research 5, 504–511 (2012).

Salman, F. et al. Redistribution of Implanted Species in Polycrystalline Silicon Films on Silicon Substrate. Defect and Diffusion Forum 264, 7–12 (2007).

Périchaud, I. Gettering of impurities in solar silicon. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 72, 315–326 (2002).

Goreslavets, N. & Rodin, A. Diffusion formation of intermediate phases and supersaturated solid solutions in the aluminum− copper system. Physics of Metals and Metallography 118, 1120–1126 (2017).

Murdock, A. T. et al. Targeted removal of copper foil surface impurities for improved synthesis of CVD graphene. Carbon 122, 207–216 (2017).

Hsieh, Y.-P., Hofmann, M. & Kong, J. Promoter-assisted chemical vapor deposition of graphene. Carbon 67, 417–423 (2014).

Chin, H. T. et al. How does graphene grow on complex 3D morphologies? Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 19, 23357–23361 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. Millimeter‐Size Single‐Crystal Graphene by Suppressing Evaporative Loss of Cu During Low Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition. Advanced Materials 25, 2062–2065 (2013).

Li, X., Cai, W., Colombo, L. & Ruoff, R. S. Evolution of Graphene Growth on Ni and Cu by Carbon Isotope Labeling. Nano letters 9, 4268–4272 (2009).

Obinata, I. & Komatsu, N. Solubility of carbon in liquid aluminium. Journal of Japan Institute of Light Metals 14, 226–230 (1964).

Luo, Z. et al. Effect of Substrate Roughness and Feedstock Concentration on Growth of Wafer-Scale Graphene at Atmospheric Pressure. Chem. Mat. 23, 1441–1447 (2011).

Ryu, J. et al. Fast Synthesis of High-Performance Graphene Films by Hydrogen-Free Rapid Thermal Chemical Vapor Deposition. ACS Nano 8, 950–956 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. Impact of Chlorine Functionalization on High-Mobility Chemical Vapor Deposition Grown Graphene. ACS nano 7, 7262–7270 (2013).

Hsieh, Y. P., Shih, C. H., Chiu, Y. J. & Hofmann, M. High-Throughput Graphene Synthesis in Gapless Stacks. Chem. Mat. 28, 40–43 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Y.-P. Hsieh and M. Hofmann acknowledge financial support from Academia Sinica (under grant SC-1070201) and the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (under grants MOST-105-2112-M-001-033-MY3 and MOST-104-2112-M-002 -026 -MY3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and Y.H. conceived the experiments, W.C. conducted experiments, M.H. developed software and fitting routines, D.N. carried out analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, DT., Chiang, WY., Su, YH. et al. Solid-diffusion-facilitated cleaning of copper foil improves the quality of CVD graphene. Sci Rep 9, 257 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36390-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36390-4