Abstract

Natural salt lick (sira) is a strategic localisation for ecological wildlife assemblage to exhibit geophagy which may act as a population dynamic buffer of prey and predators. Undoubtedly, many agree that geophagy at natural licks is linked to nutritional ecology, health and assembly places facilitating social interaction of its users. Overall, natural salt licks not only save energy of obtaining nutrient leading to health maintenance but also forms the basis of population persistence. The Royal Belum Rainforest, Malaysia (Royal Belum) is a typical tropical rainforest in Malaysia rich in wildlife which are mainly concentrated around the natural salt lick. Since this is one of the most stable fauna ecology forest in Malaysia, it is timely to assess its impact on the Malayan tiger (Panthera tigris) home range dynamics. The three-potential home ranges of the Malayan tiger in this rainforest were selected based on animal trails or foot prints surrounding the salt lick viz (e.g. Sira Kuak and Sira Batu; Sira Rambai and Sira Buluh and Sira Papan) as well as previous sightings of a Malayan tiger in the area, whose movement is dependent on the density and distribution of prey. Camera traps were placed at potential animal trails surrounding the salt lick to capture any encountered wildlife species within the area of the camera placements. Results showed that all home ranges of Malayan tiger were of no significance for large bodied prey availability such as sambar deer (Rusa unicolor), and smaller prey such as muntjacs (Muntiacus muntjac) and wild boar (Sus scrofa). Interestingly, all home range harbour the Malayan tiger as the only sole predator. The non-significance of prey availability at each home range is attributed to the decline of the Malayan tiger in the rainforest since tigers are dependant on the movement of its preferred prey surrounding natural salt licks. Thus, the information from this study offers fundamental knowledge on the importance of prey-predator interaction at salt lick which will help in designing strategy in rewilding or rehabilitation programs of the Malayan tiger at the Royal Belum Rainforest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural salt licks are mineral rich deposits that play a significant role in the ecosystem of the tropical rainforest. Similarly, the importance of salt lick in terms of physiological well-being of animals of plant-based diets is well documented1,2,3,4,5,6 and utilization should not be affected by sex and age categories. In addition, topography has been suggested to affect the accessibility of certain prey to utilize the salt lick due to the changes in mineral content of the salt lick area2,7,8.

Salt licks are a determinant of herbivore density in the rainforest, which in turns influence the density and distribution of predators9,10,11,12. Predators hunt species according to the foraging theory with preference for large bodied prey which posed the least risk and minimal investment for energy12,13. Thus, predators play an important role towards balancing the natural ecosystem14 and exerting a profound effect on vegetation densities and communities of small vertebrate7.

Soil consumption at natural licks is linked to the nutritional ecology and/or health of the users. Other than nutritional benefits, the salt licks also function as animal-assembly venues which facilitates social encounters15,16. Therefore, the existence of natural licks in a particular habitat may reduce the costs of obtaining adequate nutrition, and/or maintaining health; and thus, may be fundamental to population persistence.

The Royal Belum Rainforest in Malaysia has been established as one of habitat for Malayan tiger and houses majority of others fauna species including the barking deer or muntjac (Muntiacus muntjac), sambar deer (Rusa unicolor), Malayan sun bear (Helarctos malayanus), Malayan gaur (Bos gaurus) and Asian elephant (Elephas maximus)1,2,17,18. In Malaysia, large bodied prey species such as the sambar deer, and smaller prey like the muntjac and wild pig (Sus scrofa) have been described as the key ecological determinant of predators such as the Malayan tiger density and their potential habitat19,20. However, prey populations in the tropical rainforests are known to be decreasing due to several factors such as widespread poaching, legal hunting for consumption and deforestation for timber21,22. Inevitably, these factors contributed towards the dilution of prey abundance over a large area in the rainforest, affecting the viability of the predators such as the Malayan tiger. Despite advances in the understanding of ecological factors determining prey-predator interactions, no study has investigated how salt lick and prey availability influences the home-range of the Malayan tiger in Royal Belum Rainforest.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify the dynamics of prey species at the natural salt lick influencing the home range and possibly the declining numbers of the Malayan tiger at the Royal Belum Rainforest. Data generated from this study will unveil the current distribution of Malayan tigers near the salt licks at Royal Belum Rainforest which will enhance strategic measures in rewilding or rehabilitation of the Malayan tiger.

Methodology

Study site

The study was conducted from August 2017 to August 2020 at the Royal Belum Rainforest, Gerik Perak, which is located on the central-north of Peninsular Malaysia. This 130-million-year-old tropical rainforest is located at latitude: 5o42′37″ N and longitude: 101o31′56″ E which is covered by 2990 km2 of lowlands and hill dipterocarp virgin forests23. This rainforest is rich in flora and fauna which are characteristics of a typical rainforest of Peninsular Malaysia24. The forest is divided into two areas, the Upper Belum area, which stretches to the Malaysia-Thailand border and the Lower Belum area covered by the Temenggor Lake (Fig. 1).

The location of the Royal Belum Rainforest, Peninsular Malaysia and the tracked home range of tigers around natural salt licks. Map details: (1) Peninsular Malaysia: The map was illustrated by the author of this manuscript. (2) Royal Belum Rainforest: Generated from GPS Coordinate (https://www.gps-coordinates.net/); Latitude: 5°42′37″N; Longitude: 101°31′56″E.

Permit of data sampling in the Royal Belum Rainforest was approved by the Perak State Park, Malaysia, and Department of Wildlife National Parks (PERHILITAN) Peninsular Malaysia. Three sampling areas or home ranges were chosen based on the precision of ecological objectives and responses metrics such as wildlife relative abundance, presence of preferred prey (e.g. sambar deer, muntjac and wild pig) utilizing the saltlicks and the sighting of a predatory species (e.g. the Malayan tiger) in the area. The information above was obtained from discussions with the local rangers and local indigenous people who are well versed on the forest ecology. Malayan tigers are generally solitary animals whose movement is dependent on its prey, thus the study assumes that areas containing salt licks might be home ranges of an individual Malayan tiger. The first sampling area at Sungai Tiang is located approximately 8 km from the jetty at the Lower Belum, Complex (Fig. 1). Three salt licks namely Sira Kuak, Sira Batu and Sira Tanah were identified at Sungai Tiang. The second, at Sungai Kejar, located approximately 12 km from Sungai Tiang and is consisted of two salt licks, namely Sira Rambai and Sira Buloh. The third, at Sungai Papan, has only one large salt lick which is Sira Papan.

Camera trap setting

A total of 66 camera traps (LTL Acorn 5210) were placed at strategic locations to identify the frequency of wildlife appearances at all studied salt licks. The number of cameras necessary for monitoring of wildlife at surrounding area of salt licks was in accordance to the size of sample area between 20 and 92 m22,25. Each salt lick was tracked by three camera traps, whereas other eight camera traps were placed in areas around the salt lick to enhance the potential of capturing images of the tiger. The placement of the camera was also based on recommendations given by the native’s experts who always encounter tiger footprints around the vicinity of the salt lick.

Cameras at saltlicks were placed on various trees around saltlicks directed towards animal paths heading towards the salt licks or drinking sites. The cameras at saltlicks were aimed from a further distance to incorporate a broader angle to obtain a larger view on saltlicks. This was done to obtain a better view for species identification. In regards to the predators, the cameras were placed about 1.5 m off the ground (to commensurate the average height of a tiger) and the cameras were immobilized using bungee cords wrapped around the tree (Fig. 2). Cameras were targeted at wildlife trails 10–50 m outside the saltlicks. Large pathways were incorporated to increase the probability of obtaining an image of a species outside saltlicks.

The placement of cameras around a natural salt licks in the Royal Belum Rainforest. Map details: The background featuring a DEM-based image is from the ArcGIS software application (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) with GPS reference coordinate; Latitude: 5°42′37″N; Longitude: 101°31′56″E.

Each 66-gigabyte memory card (SanDisk, Western Digital) camera is charged with eight AA batteries (Energizer MAX, Energizer Holdings Inc.). The batteries and memory card has a span of approximately two months depending on the frequency of captured images and footages of any moving of objects. The camera is also equipped with infrared sensors that will trigger recording of images and footages upon any movement of animals on a 20 s short video modes. New set of batteries and memory card were replaced 8 times throughout the 36 months duration of the study.

The study was conducted in a gazetted forest, where only those with an authorised permit are allowed entry to minimised theft. However, during the 36 months of sampling, only 1 out of the 6 cameras was stolen and disposed off at Sira Papan. The ditched camera devoid of the memory card was found about 20 m from the initial placement. Nevertheless, although about 50% of the installed cameras were either destroyed by elephants or being weathered by humidity, the data from the memory cards were intact.

Malayan tiger identification

This study attempts to identify the captured images of Malayan tigers. Several established methods have been described for identification of adult tigers in the wild using stripes26, pugmarks27, DNA28, and smell29. This study opted for the stripe identification, which is the most common method used for captured image identification of the tigers in the wild26,30,31.

Data recording by the camera trap

All data from the memory cards were played back on Microsoft Windows media player, and the images were tabulated using an ethogram procedure according to the species and number of sightings at each salt lick. Technically, animals of the same species captured within a 30-min period were counted as one individual. Multiple animals of the same species in a single frame were also counted as one individual.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from the studies were analysed with MedCalc statistical software version 19.0.4 using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures followed by post hoc least significant difference test. All data were expressed as mean ± SD and only P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the number of different species at three different of home range; Sungai Tiang, Sungai Papan and Sungai Kejar at Royal Belum Rainforest, Gerik Perak. There is no significant different on the prey availability (e.g. muntjac, sambar deer and wild boar) and presence of predators such as the Malayan tiger at all home ranges.

Table 2 shows the species, salt licks location and frequency of sighting during the study period. Muntjac and wild boar are two species with higher frequency of sightings at the salt licks.

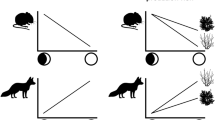

The image of selected wildlife at different home range spotted by the camera traps according to the date and time as stated in the Supplementary Fig. S1–S3. It was revealed that the prey species were either grazing, foraging and exhibiting geophagy at and surrounding natural the salt licks. This includes wild hog either alone or as a passel, muntjac, sambar deer and gaur.

The stripe pattern and close-up image used for identification of a tiger is tabulated in Table 3. Although it was unfortunate that captured view of images is beyond control and could not be standardised, clearly all four Malayan tigers donned different stripe pattern.

Discussion

It was documented that the home range for muntjac32, sambar deer33, wild hog34, gaur35 and tiger36 are 0.6–1.68, 2.4–11.8, 0.6–48.3, 32–169 and 70–294 km2, respectively. Based on the stated home range data, the prey species found in the study presented here showed do overlap or provide evidence of their likely encounters with the Malayan tiger. Likewise, it is very likely that these tigers were also “resident” predators in this locality.

In this study, the presence of prey such as muntjac, sambar deer and wild hog are widespread in all home range at the Royal Belum Rainforest. Surprisingly, this contradicts earlier findings denoting their lowest in Malaysia rainforest37. It is likely that the latter findings was conducted in a different geographical location (National Park) where activities favouring prey reduction were much more intense18,21. However, this finding confirmed the greater availability of prey population in this locality based on salt lick fauna surveillance2. Thus, the abundant availability of prey at these salt licks renders a diet selection for the predator which is a vital factor towards equilibrium prey-predator dynamics in the tropical rainforest.

The comparable frequency of prey visiting the natural salt licks between all sites (e.g. Sungai Tiang, Sungai Kejar and Sungai Papan) strengthen the fact that these species are attracted to this site due to the functionality of salt licks. As long as salt licks are functional in providing minerals, differences in herbivore population around natural salt licks is unexpected unless it is influenced by external factors such as an increase in number of predators. The inference made from this study that only one carnivore was documented around each salt lick explains the absence of a top-down regulator affecting herbivore occurrence in that area.

The spotting of only one adult Malayan tiger at each home range further support tigers to be solitary and territorial, and conformed to their documented home range (7–294 km2). Likewise, this finding is also denotes that despite the failure in getting a full stripe profile of each spotted tiger, they were actually a different individual.

The preferred prey of the Malayan tiger is namely the sambar deer, wild hog and muntjac37,38,39,40 that were frequently noted around the salt licks indicated the impact of salt licks as an invaluable hunting grounds for this species. This could indicate that the Malayan tiger localises its home range, and roams around natural salt licks with confidence of capturing prey of its choice8,41.

The findings from the study presented here cast the pivotal role of predators stabilising the fauna ecosystem by influencing the population of prey communities in the salt lick area4,42. Thus, the conservation of natural salt lick is not only important for prey, but also has direct bearing to the longevity and survival of the Malayan tigers.

Undoubtedly, this study showed the dependence of the Malayan tigers in the Royal Belum Rainforest on the density and abundance of prey species. Similarly, the due to their dependence on natural salt licks, prey species tend to habituate at the natural salt licks which directly invoke the presence of tiger to this area. We believe that the ‘home-range’ of the territorial carnivores are based around clusters of natural salt licks located in the tropical rainforest. In fact, the long distance between different home range (as shown in Fig. 1) combined with a low prey abundance of tropical rainforests, will indirectly lead to the dispersal and isolation of our already severely debilitated number of adult tigers42. In addition, large home ranges, wide dietary breadth and dense forested habitats have precluded precise quantification of diet constituents and accurate sampling techniques for determining available prey base in most of the tiger’s geographical range39,43.

Hence, this study puts a postulate that tigers in the Royal Belum Rainforest are too dispersed and isolated from one another to maintain a healthy, breeding, and genetically diverse population. Tigers are localising around areas of prey concentration at natural salt licks; thus, they do not need to roam large areas of tropical rainforests in search of prey. This puts them in dispersed areas, as salt licks are located in randomly distributed locations throughout the tropical rainforests (Fig. 3). Besides low prey populations, forest fragmentation and continued poaching are leading towards low occurrence of tigers in the same areas, and isolation of tigers in fragmented forests with no way to maintain the population37,40. It appears that poaching activity exist out within the Royal Belum Rainforest. In our study, we encountered evidence of poaching in the form of a Malayan gaur which was missing a hoof in the hind right limb (Supplementary Fig. S4). This injury could have been acquired from a snare meant for animals like the Malayan tiger or sun bears which are sought after for traditional medicine21.

The distribution of salt licks at the Royal Belum Rainforest. Map details: Royal Belum Rainforest: Generated from GPS Coordinate (https://www.gps-coordinates.net/); Latitude: 5°42′37″N; Longitude: 101°31′56″E.

Data availability

The location and statistical data used in this study are available included within this article. Some of confidential data are restricted by the Royal Belum State Park in order to protect the endangered species located within the area of study. Data are available from the corresponding author, Associate Professor Dr. Hafandi Ahmad (hafandi@upm.edu.my) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

References

Hamdan, A. et al. A preliminary study of mirror-induced self-directed behaviour on wildlife at the Royal Belum Rainforest Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 10, 14105. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71047-1 (2020).

Lazarus, B. A. et al. Topographical differences impacting wildlife dynamics at natural salt licks in the Royal Belum Rainforest. Asian J. Conserv. Biol. 8(2), 97–101 (2019).

Brightsmith, D. J., Taylor, J. & Phillips, T. D. The roles of soil characteristics and toxin adsorption in avian geophagy. Biotropica 40, 766–774 (2008).

Ayotte, J. B., Parker, K. L., Arocena, J. & Gillingham, M. P. Chemical composition of lick soils: functions of soil ingestion by four ungulate species. J. Mammal. 87(5), 878–888 (2006).

Matsubayashi, H. et al. Importance of natural licks for mammals in Bornean Inland Tropical Rainforest. Ecol. Res. 22, 742 (2006).

Tracy, B. F. & McNaughton, S. J. Elemental analysis of mineral licks from the Serengeti National Park, the Konza Prairie and Yellowstone National Park. Ecography 18, 91–94 (1995).

Razali, N. B. et al. Physical factors at salt licks influenced the frequency of wildlife visitation in the Malaysian tropical rainforest. Trop. Zool. 33(3), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.4081/tz.2020.69 (2020).

Owen-Smith, N. & Mills, M. Predator-prey size relationships in an African large-mammal food web. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 173–183 (2008).

Mathers, K. L., Rice, S. P. & Wood, P. J. Predator, prey, and substrate interactions: the role of faunal activity and substrate characteristics. Ecosphere 10(1), e02545 (2019).

Sobral, M. et al. Mammal diversity influences the carbon cycle through trophic interactions in the Amazon. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1670–1676 (2017).

Stevens, A. Dynamics of predation. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 3(10), 46 (2010).

Lima, S. T. Putting predators back into behavioral predator–prey interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17(2), 70–75 (2002).

Cuyper, A. D. et al. Predator size and prey size–gut capacity ratios determine kill frequency and carcass production in terrestrial carnivorous mammals. Oikos https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.05488 (2018).

Terborgh, J. et al. Ecological meltdown in predator-free forest fragments. Science 294(5548), 1923–1926 (2001).

Couturier, S. & Barrete, C. The behaviour of moose at natural mineral springs in Quebec. Can. J. Zool. 66, 522–528 (1987).

Ruggiero, R. D. & Fay, J. M. Utilization of termitarium soils by elephants and its ecological implications. Afr. J. Ecol. 32, 222–232 (1994).

Shahfiz, M. A. et al. Checklist of vertebrates at Primary Linkages 2 (PL2) of the central forest spine ecological corridor in Belum Temengor Forest Reserves, Perak, Peninsular Malaysia. Malays. For. 82(2), 463–485 (2019).

Liyana, N. M., Othman, Z., Wahid, A. R. & Hakimie, A. A. Habitat suitability prediction model of wildlife at Royal Belum State Park using geographical information system. Int. J. Geoinform. 12(2), 1–8 (2016).

Kawanishi, K. et al. The Malayan tiger. In In Noyes Series in Animal Behavior, Ecology, Conservation and Management, Tigers of the World 2nd edn (eds Tilson, R. & Nyhus, P. J.) 367–376 (William Andrew Publishing, Norwich, 2010).

Lynam, A. J., Laidlaw, R., Wan Noordin, W. S., Elagupillay, S. & Bennett, E. L. Assessing the conservation status of the tiger Panthera tigris at priority sites in Peninsular Malaysia. Oryx 41(4), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605307001019 (2007).

Kawanishi, K., Rayan, M. D., Gumal, M. T. & Shepherd, C. R. Extinction process of the sambar in Peninsular Malaysia. Deer Spec. Group Newsl. N. 26, 48–59 (2014).

Simcharoen, A. et al. Female tiger Panthera tigris home range size and prey abundance: important metrics for management. Oryx 48(3), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605312001408 (2014).

Kedri, K. et al. Distribution and ecology of Rafflesia in Royal Belum state park, Perak, Malaysia. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 7(229), 292–296 (2018).

Misni, A., Rauf, A., Rasam, A. & Buyadi, A. S. N. Spatial analysis of habitat conservation for hornbills: a case study of Royal Belum-Temengor forest complex in Perak Sate Park Malaysia. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 25(S), 11–20 (2017).

Rovero, F., Zimmermann, F., Berzi, D. & Meek, P. Which camera trap type and how many do I need? A review of camera features and study designs for a range of wildlife research applications. Hystrix 2, 6318 (2013).

Liu, N., Zhao, Q., Zhang, N., Cheng, X., & Zhu, J. Pose-guided complementary features learning for Amur tiger re-identification, in 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Korea (South), 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW.2019.00038 (2019).

Sharma, S., Jhala, Y. & Sawarkar, V. B. Identification of individual tigers (Panthera tigris) from their pugmarks. J. Zool. 267, 9–18 (2005).

Cho, Y. et al. The tiger genome and comparative analysis with lion and snow leopard genomes. Nat. Commun. 4, 2433 (2013).

Kerley, L. L. Using dogs for tiger conservation and research. Integr. Zool. 5, 390–396 (2010).

Li, S., Li, J., Tang, H., Qian, R., & Lin, W. ATRW: a benchmark for Amur tiger re-identification in the wild, in Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’20), October 12–16, 2020, Seattle, WA, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/3394171.3413569 (ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2020).

Shi, C. et al. Amur tiger stripes: Individual identification based on deep convolutional neural network. Integr. Zool. 15(6), 461–470 (2020).

McCullough, D. R., Pei, K. C. J. & Wang, Y. Home range, activity patterns, and habitat relations of Reeves’ muntjacs in Taiwan. J. Wildl. Manag. 64(2), 430. https://doi.org/10.2307/3803241 (2000).

Chatterjee, D., Sankar, K., Qureshi, Q., Malik, P. K. & Nigam, P. Ranging pattern and habitat use of sambar (Rusa unicolor) in Sariska Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, western India. DSG Newsl. 26, 60–71 (2014).

Garza, S. J., Tabak, M. A., Miller, R. S., Farnsworth, M. L. & Burdett, C. L. Abiotic and biotic influences on home-range size of wild pigs (Sus scrofa). J. Mammal. 99(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyx154 (2018).

Sankar, K. et al. Home range, habitat use and food habits of re-introduced gaur (Bos gaurus gaurus) in Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, Central India. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 6(1), 50–69 (2013).

Simcharoen, A. et al. Ecological Factors that influence sambar (Rusa unicolor) distribution and abundance in western Thailand: Implications for tiger conservation. Raffles Bull. Zool. 62, 100–106 (2014).

Mark Rayan, D. & Linkie, M. Managing threatened ungulates in logged-primary forest mosaics in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 15(12), e0243932. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243932 (2020).

McClure, M. L. et al. Modeling and mapping the probability of occurrence of invasive wild pigs across the contiguous United States. PLoS ONE 10(8), e0133771. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133771 (2015).

Ickes, K. Hyper-abundance of native wild pigs (Sus scrofa) in a lowland dipterocarp rain forest of Peninsular Malaysia. Biotropica 33(4), 682–690 (2001).

Saunders, G. & McLeod, S. Predicting home range size from the body mass or population densities of feral pigs, sus scrofa (Artiodactyla: Suidae). Aust. J. Ecol. 24, 538–543 (1999).

Abrams, P. A. & Matsuda, H. Prey adaptation as a cause of predator-prey cycles. Evolution 51, 1742–1750 (1997).

Zhang, C., Minghai, Z. & Philip, S. Does prey density limit Amur tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) recovery in north-eastern China. Wildl. Biol. 19(4), 452–461 (2013).

Majumder, A. et al. Home ranges of Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris L.) in Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, Central India. Wildl. Biol. Pract. 8, 36–49 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Research project was partially sponsored by the Putra Grant Scheme (IPS), Universiti Putra Malaysia (9680800). The authors would like to thank the authorities at the Royal Belum State Park, Perak for approving the permit for this research and for their cooperation. The authors would also like to thank the research officers at the Pulau Banding Research Centre Mr. Ahmad Najmi Nik Hassan and Mr. Mohd Syaiful Mohammad for their guidance, advice and cooperation to help make this project a success, with their experience in the Royal Belum Rainforest and their contact with the locals. We would also like to thank our boat navigator, Mr. Azman for his contribution in this study. Not forgetting the local indigenous people at the Royal Belum Rainforest, for being a guide in the forest, as well as not disturbing the cameras places in the rainforest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.A. and B.A.L. conceived and designed the experiments; H.A., B.A.L., M.M.A.H.S., A.H. and A.C.A. contributed to sampling; H.A. and B.A.L. contributed to data analysis and drafted the manuscript; H.A., A.C.A., M.H.M.N., F.M.K., H.A.H. and N.M.M. edited and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lazarus, B.A., Che-Amat, A., Abdul Halim Shah, M.M. et al. Impact of natural salt lick on the home range of Panthera tigris at the Royal Belum Rainforest, Malaysia. Sci Rep 11, 10596 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89980-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89980-0

This article is cited by

-

Temporal niche partitioning among sympatric wild and domestic ungulates between warm and cold seasons

Scientific Reports (2024)