Abstract

Otitis media (OM) is common among young children and is related to hearing loss. We investigated the association between maternal insecticide use, from conception to the first and second/third trimesters, and OM events in children in the first year of age. Data from Japan Environment and Children's Study were used in this prospective cohort study. Characteristics of patients with and without history of OM during the first year of age were compared. The association between history of OM in the first year and insecticide use was evaluated using logistic regression analysis. The study enrolled 98,255 infants. There was no significant difference in the frequency of insecticide use between groups. Insecticide use of more than once a week from conception to the first trimester significantly increased the occurrence of OM in children in the first year (odds ratio [OR] = 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.67). The association between OM in the first year and insecticide use from conception to the first trimester was only significant in the group without daycare attendance (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.30–2.38). Maternal insecticide use more than once a week from conception to the first trimester significantly increased OM risk in offspring without daycare attendance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Otitis media (OM) is a spectrum of diseases, including acute otitis media (AOM), OM with effusion, and chronic suppurative OM1. OM is a common disease among children worldwide. The average AOM incidence was 10.8 new episodes per 100 people per year2. Streptococcus pneumoniae, non-typable Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis are three major bacterial pathogens which cause OM3. Many host and environmental factors can increase the risk of OM. Factors include young age4, male sex5, maternal age < 20 years5, non-Hispanic white ethnicity5, family history of recurrent OM6, exposure to tobacco smoke6, having an older sibling7, the use of a pacifier8, trisomy 219, gestational week10, birth weight11, maternal occupation12, and daycare attendance4,7,13. Attending daycare and having siblings (generally older) were consistent risk factors for OM with effusion14,15,16. Preventive factors were exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months17.

Pyrethroids and organochlorine are two major insecticides. There were reports of insecticide exposure during pregnancy influencing the offspring. Perinatal exposure to pyrethroids was associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at 2–4 years of age18. Maternal prenatal pyrethroid metabolite concentrations were not consistently associated with children’s cognitive scores19. An adverse association of prenatal exposure to pyrethroids as measured by urinary metabolites with birth weight was also reported20. Moreover, maternal exposure to pyrethroid insecticide during pregnancy strangely had a positive effect on infant development21. Regarding the association between OM history and insecticide exposure, prenatal organochlorine exposure could be a risk factor for AOM in Inuit infants22.

We aimed to investigate the association between children’s OM history at the age of one and the frequency of maternal insecticide use both from conception to the first and second/third trimesters.

Results

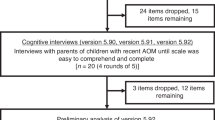

We recruited 104,065 fetuses and excluded 346 stillbirth cases, 1192 abortion cases, 2281 missing values, and 1991 multiple births. Finally, we included 98,255 infants in the present study (Fig. 1).

We compared the frequency of maternal insecticide use both after conception to the first and second/third trimesters between the OM group and no OM group (Table 1).

Whether children were affected by OM during the first year was associated with that mothers used insecticide more than once a week from becoming pregnant to the first trimester (odds ratio [OR] = 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.67). Whether children were affected with OM during the first year was not associated with that mothers used insecticide from becoming pregnant to the second/third trimester (Table 2).

The result of estimation using multiple imputations confirmed the outcome of the logistic regression analysis (Table 3). In subgroup analysis, whether children were affected with OM for the first year was significantly associated with that mothers used insecticide more than once a week from conception to the first trimester in sub-group of no attendance to daycare (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.30–2.38) (Table 4).

There was no significant association between whether children were affected with OM during the first year and that mothers used insecticide from conception to the second/third trimester in all subgroups (Table 5).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the correlation between OM history in the first year in children and maternal insecticide use from conception to the first and second/third trimesters using multivariate regression analysis.

Previous studies have shown no association between prenatal domestic insecticide exposure and OM episode during early childhood23. The population was 3,421 women before 19th week of gestation in a region in France. The women occupationally exposed to pesticide were excluded. Outcome was OM episode in the first two years in children and was collected with questionnaire from mothers. Exposure included eight different types of home pesticides for plants, fleas and ticks, insects, rodents, and house frame treatment. The number of times domestic insecticide was used was only 1,426. Exposure scores were rated from 1 (low exposure) to 3 (high exposure). The differences between the previous study and ours include population size and exposure period, outcome assessment period, and the details of pesticide use. Our population was much larger and covered a wider geographical location compared with the previous study. The period of maternal pesticide exposure was until 19th week of gestation and the second/third trimester. We focused not only on this period, but from conception to the first trimester as well; therefore, we can reveal the association between OM for a more limited period and maternal pesticide use for a more important gestational period in a larger population compared with the previous study. Maternal insecticide use from conception to the first trimester at the frequency of more than once a week may be avoided if mothers do not intend to have their children attend the daycare at the age of 1 year.

The mechanism of relation between use of insecticide and OM may be caused by deteriorated immune function. Previous studies showed the level of IgA were lower in breast-fed infants from prenatally organochlorine-exposed mothers rather than in bottle-fed infants both at seven and at 12 months22. In other study, the strongest dose-dependent association between prenatal exposure to organochlorine and ear infection was shown24. Perinatal accumulation of organochlorine to mother may negatively affect the immune system in infants.

In our analysis presenting at Tables 2 and 3, living with older siblings, the history of maternal chronic OM, and daycare attendance increased the incidence of OM. Thus, our results were consistent with the findings of the previous studies5,25,26.

The outcome of the present study may contribute to decreased otitis media prevalence and incidence in children for the first year when pregnant woman are advised to avoid using insecticide. As the cost of OM treatment in the United States is estimated at between three to four billion dollars27, decreasing OM results in huge financial savings. Approximately 17 percent of children have three or more episodes during a 6 months period27. Preventing OM decreases the burden that is placed on parents who have to visit clinics and take time off work.

One limitation of this study was the lack of detailed information on the type and amount of mothers’ insecticide exposure. It is important which insecticide and how much dose mother used between conception both to the first trimester and second/third trimesters.

Maternal insecticide use before conception may also be a limitation because of recall bias. Some mothers may misunderstand the timing of insecticide use or may misunderstand other products, such as pesticides as an insecticide.

Another limitation is that we cannot exclude the possibility of unknown confounding factors that influence the frequency of maternal insecticide use.

In conclusion, despite these limitations, we revealed that maternal insecticide use more than once a week in the group without daycare attendance at the age of 1 year was associated with the history of OM in the first year of age of children. Thus, we need further investigation into how maternal insecticide use influences OM in their children.

Methods

The STROBE checklist was followed in this study.

Study design and participants

We used data from the Japan Environment and Children's Study (JECS) in this prospective cohort study. The JECS is a national birth cohort study investigating the environmental factors that potentially affect the health and development of children in Japan28. The details of the JECS have been previously described29. All participants were recruited between January 2011 and March 2014. The present study used the "jecs-an-20180131" dataset, which was released in March 2018. Of these, we excluded stillbirth, abortion, missing values, and multiple birth patients.

Data collection

Data regarding first year OM history, breastfeeding for the first 6 months, daycare use, pneumococcal, and Hib vaccine were collected from a parental self-reported questionnaire. Data regarding live births or stillbirths, singleton or multiple births, sex, gestational weeks, birth weight, maternal age, and whether the child was diagnosed with trisomy 21 were transcribed from medical records by physicians, midwives/nurses, and research co-ordinators.

The primary outcome was obtained by “C1y questionnaire”, which asked caregivers when their children were at the age of 1 “Has your child been diagnosed with OM by a doctor?” The outcome variable was binomial: no diagnosis with OM as 0 and diagnosis with OM as 1. We did not distinguish between acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion in this questionnaire. Further, there was no data how OM was treated in this questionnaire.

The exposure factors were maternal occupational use of insecticide more than half a day from conception to the first and second/third trimesters. The question was, “What was the frequency of occupational use of insecticide for more than half a day during pregnancy?”. We obtained this information from the questionnaire to mother” M-T1 questionnaire”, filled in the first trimester, and “M-T2 questionnaire”, filled in the second/third trimester30. We classified these variables as follows: No as 1, 1–3 times per month as 2, and 1–6 times a week and everyday as 3.

We selected the covariates below because they were known risk factors of OM as described in the introduction section. Although maternal infertility treatment was not reported to be associated with OM; primary ciliary dyskinesia, which causes both chronic OM and infertility, is inherited31. Therefore, we selected maternal infertility treatment as covariate. Other covariates included sex, gestational weeks, birth weight, exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months, living with older siblings at 6 months, nursery attendance at the age of one, maternal history of chronic OM, maternal age, a history of pneumococcal vaccine, and Hib vaccine, whether the child was diagnosed with trisomy 21 or not, and history of fertility treatment. We also selected smoking around children, such as paternal and maternal smoking habits, maternal exposure to secondhand smoking, and household smoking at the age of 1 month. We focused on maternal occupation, especially farmers. However, the number of farmers was very small. Instead, we used major occupational categories. We recorded the number of mothers in every major maternal occupational category.

We classified the binomial variables as follows: sex of the child: male as 1, female as 2; living with siblings at 6 months, daycare use at a year old, maternal history of chronic OM, history of pneumococcal vaccine and Hib vaccine, children with trisomy 21, history of fertility treatment: No as 0, yes as 1.

Furthermore, we classified categorical variables as follows: gestational weeks32,33: 37 to 41 weeks as 1, < 37 weeks as 2, ≥ 42 weeks as 3; the birth weight of child: 2.5 -4 kg as 1, < 2.5 kg as 2, ≥ 4 kg as 3; maternal age: 30–34 years as 1, 25–29 years as 2, < 25 years as 3, and ≥ 35 years as 4; paternal and maternal smoking habits: never as 1, "previously did, but quit before realizing current pregnancy" as 2, "previously did, but quit after realizing current pregnancy" as 3, and currently smoking as 4; the frequency of maternal exposure to secondhand smoking: never as 1, more than once a week as 2; household smoking at the age of 1 month: no one as 1, someone smoking at a place far from the baby as 2, smoking at a location near the baby as 3. Maternal occupational categories: full-time homemaker as 1, professional and technicians as 2, clerical support workers as 3, service workers as 4, the others as 5 because, of major occupational categories, the biggest category was full-time homemakers (n = 23,890), followed by professional and technicians (n = 18,758), clerical support workers (n = 14,633), service workers (n = 12,901), and the others (n = 14,308). For all variables, we set the minimum category number as a reference control.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). First, we compared patient characteristics between the OM history and non-OM history groups for the first year in children. Second, we analyzed the relationship between whether children were affected with OM during the first year and maternal insecticide use, both from conception to the first trimester and from conception to the second/third trimesters, using logistic regression analysis. Third, we performed sensitivity analysis by the multiple imputation method since there were many missing values. Finally, we performed sub-group analysis of the relationship between whether children were affected with OM for the first year and maternal insecticide use both from conception to the first trimester, and from conception to the second/third trimesters using logistic regression analysis in three subgroups. These groups included whether children had a sibling living with them when they were 6 months, whether children attended daycare at the age of one, and whether the mother had a history of chronic OM. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The JECS protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of the Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies and the Ethics Committees of all participating institutions: the National Institute for Environmental Studies that leads the JECS, the National Center for Child Health and Development, Hokkaido University, Sapporo Medical University, Asahikawa Medical University, Japanese Red Cross Hokkaido College of Nursing, Tohoku University, Fukushima Medical University, Chiba University, Yokohama City University, University of Yamanashi, Shinshu University, University of Toyama, Nagoya City University, Kyoto University, Doshisha University, Osaka University, Osaka Medical Center Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Hyogo College of Medicine, Tottori University, Kochi University, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kyushu University, Kumamoto University, University of Miyazaki, University of Ryukyu (Ethical number: No.100910001). We confirmed that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. We obtained written informed consent from all participants before participation in the present study.

Data availability

Data are unsuitable for public deposition due to ethical restrictions and the legal framework of Japan. It is prohibited by the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of May 30, 2003, amendment on September 9, 2015) to publicly deposit data containing personal information. Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects enforced by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also restrict the open sharing of epidemiologic data. All inquiries regarding access to data should be sent to jecs-en@nies.go.jp. The person responsible for handling questions sent to this email address is Dr. Shoji F. Nakayama, JECS Program Office, National Institute for Environmental Studies.

References

Schilder, A. G. M. et al. Otitis media. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2, 16063 (2016).

Monasta, L. et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: Systematic review and global estimates. PLoS ONE 7, e36226. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036226 (2012).

Coker, T. R. et al. Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children: A systematic review. JAMA 304, 2161–2169 (2010).

Todberg, T. et al. Incidence of otitis media in a contemporary danish national birth cohort. PLoS ONE 9, e111732. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111732 (2014).

Macintyre, E. A. et al. Otitis media incidence and risk factors in a population-based birth cohort. Paediatr. Child Health 15, 437–442 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Risk factors for chronic and recurrent otitis media: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9, e86397. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086397 (2014).

Brennan-Jones, C. G. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for parent-reported recurrent otitis media during early childhood in the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study. J. Paediatr. Child Health 51, 403–409 (2015).

Salah, M., Abdel-Aziz, M., Al-Farok, A. & Jebrini, A. Recurrent acute otitis media in infants: Analysis of risk factors. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 77, 1665–1669 (2013).

Austeng, M. E. et al. Otitis media with effusion in children with in Down syndrome. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 77, 1329–1332 (2013).

Kørvel-Hanquist, A. et al. Risk factors of early otitis media in the danish national birth cohort. PLoS ONE 11, e0166465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166465 (2016).

Engel, J., Anteunis, L., Volovics, A., Hendriks, J. & Marres, E. Risk factors of otitis media with effusion during infancy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 48, 239–249 (1999).

Kalcioglu, M. T. et al. Prevalence of and factors affecting otitis media with effusion in children in the region from Balkans to Caspian basin; A multicentric cross-sectional study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 143, 110647 (2021).

La De Hoog, M. et al. Impact of early daycare on healthcare resource use related to upper respiratory tract infections during childhood: Prospective WHISTLER cohort study. BMC Med. 12, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-107 (2014).

Bennett, K. E. & Haggard, M. P. Accumulation of factors influencing children’s middle ear disease: Risk factor modelling on a large population cohort. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 52, 786–793 (1998).

Dewey, C., Midgeley, E. & Maw, R. The relationship between otitis media with effusion and contact with other children in a British cohort studied from 8 months to 3 1/2 years. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 55, 33–45 (2000).

Rovers, M. M., Zielhuis, G. A., Ingels, K. & van der Wilt, G. J. Day-care and otitis media in young children: A critical overview. Eur. J. Pediatr. 158, 1–6 (1999).

Bowatte, G. et al. Breastfeeding and childhood acute otitis media: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 104, 85–95 (2015).

Dalsager, L. et al. Maternal urinary concentrations of pyrethroid and chlorpyrifos metabolites and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in 2–4-year-old children from the Odense Child Cohort. Environ. Res. 176, 108533 (2019).

Viel, J. F. et al. Pyrethroid insecticide exposure and cognitive developmental disabilities in children: The PELAGIE mother-child cohort. Environ. Int. 82, 69–75 (2015).

Ding, G. et al. Prenatal exposure to pyrethroid insecticides and birth outcomes in Rural Northern China. J. Exp. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 25, 264–270 (2015).

Hisada, A. et al. Maternal exposure to pyrethroid insecticides during pregnancy and infant development at 18 months of age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 52 (2017).

Dewailly, E. et al. Susceptibility to Infections and Immune Status in Inuit Infants Exposed to Organochlorines. Environ. Health Perspect. 108, 205–211 (2000).

Buscail, C. et al. Prenatal pesticide exposure and otitis media during early childhood in the PELAGIE mother-child cohort. Occup. Environ. Med. 72, 837–844 (2015).

Dallaire, F. et al. Acute infections and environmental exposure to organochlorines in Inuit infants from Nunavik. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 1359–1364 (2004).

Chen, K. W. K. et al. Childhood otitis media: Relationship with daycare attendance, harsh parenting, and maternal mental health. PLoS ONE 14, e0219684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219684 (2019).

Daly, K. A. et al. Epidemiology of otitis media onset by six months of age. Pediatrics 103, 1158–1166 (1999).

Tephen, S. & Erman, B. Otitis media in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 332, 1560–1565. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199506083322307 (2009).

Kawamoto, T. et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health 14, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-25 (2014).

Michikawa, T. et al. Baseline profile of participants in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). J. Epidemiol. 28, 99–104 (2018).

Iwai-Shimada, M. et al. Questionnaire results on exposure characteristics of pregnant women participating in the Japan Environment and Children Study (JECS). Environ. Health Prev. Med. 23, 1–15 (2018).

Boon, M., Jorissen, M., Proesmans, M. & De Boeck, K. Primary ciliary dyskinesia, an orphan disease. Eur. J. Pediatr. 172, 151–162 (2013).

Cui, M. et al. Prenatal tobacco smoking is associated with postpartum depression in Japanese pregnant women: The Japan environment and children’s study. J. Affect. Disord. 264, 76–81 (2020).

Suga, R. et al. Factors associated with occupation changes after pregnancy/delivery: Result from Japan Environment & Children’s pilot study. BMC Womens. Health 18, 1–11 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We want to express our gratitude to all participants and cooperate with Co-operating health care providers in the Japan Environment and Children's Study (JECS).

Members of the JECS Group as of 2021: Michihiro Kamijima (principal investigator, Nagoya City University, Nagoya, Japan), Shin Yamazaki (National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan), Yukihiro Ohya (National Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan), Reiko Kishi (Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan), Nobuo Yaegashi (Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan), Koichi Hashimoto (Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan), Chisato Mori (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan), Shuichi Ito (Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan), Zentaro Yamagata (University of Yamanashi, Chuo, Japan), Hidekuni Inadera (University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan), Takeo Nakayama (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), Hiroyasu Iso (Osaka University, Suita, Japan), Masayuki Shima (Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan), Youichi Kurozawa (Tottori University, Yonago, Japan), Narufumi Suganuma (Kochi University, Nankoku, Japan), Koichi Kusuhara (University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, Japan), and Takahiko Katoh (Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan).

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the above government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

T.U. and M.S. conceived the study. M.S. and Y.T. aided in data collection. T.U. was involved in manuscript writing, figure preparation, and table creation. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Utsunomiya, T., Taniguchi, N., Taniguchi, Y. et al. Association between maternal insecticide use and otitis media in one-year-old children in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Sci Rep 12, 1365 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05433-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05433-2