Abstract

In this study, we observed that four congeners, including naphthalene (Nap), acenaphthylene (Acy), phenanthrene (Phe), and benz(a)anthracene (BaA), are the characteristic congeners for predicting the emission and the sediment concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). A novel multiple relationship of the total PAHs concentrations (C∑PAHs) in sediments with the concentrations of four congeners was established (p < 0.01, R2 = 0.95) using published data over the past 30 years. Moreover, the multiple linear relationship of the total PAHs emission factors with the emission factors of four congeners was also established (p < 0.01, R2 = 0.99). Interestingly, the ratio of multicomponents coefficient from the multiple linear relationship in sediments to that from the multiple linear relationship in emission sources correlated positively with octanol–water partition coefficient (logKow) (p < 0.01, R2 = 0.88) of the four PAHs congeners. Therefore, a novel model was established to predict CΣPAHs in sediments using the emissions and logKow of the four characteristic PAHs congeners. The percent sample deviation between calculated C∑PAHs and their observed values was 54%, suggesting the established model can accurately predict CΣPAHs in sediments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a group of persistent organic contaminants that originate from the incomplete combustion of organic matter (such as biomass and coal) and non-combustion emissions of petrogenic processes1,2,3. United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and European Union (EU) have identified sixteen PAHs (Table S1) as priority pollutants due to their toxicity and risks to human health and the environment4,5,6,7. For example, PAHs in sediments can pose detrimental effects on benthic organisms and pelagic organisms8,9. Therefore, PAHs concentrations in sediments have been widely investigated in the past decades for assessing their risks10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. The common method for the quantification of PAHs in sediments is chromatography, including gas chromatography or liquid chromatography, coupled with mass spectrometry19,20,21. However, the whole process of chromatographic analysis for PAHs in sediments is tedious and cost-consuming. Moreover, this method may be potentially damaging for the environment because the analysis typically requires a pre-concentration procedure, which may use large volumes of organic solvents for extraction and clean-up22,23,24. For example, the frequently used organic solvents, dichloromethane19,20,21, can damage human nervous system and even the functions of liver and kidney through skin mucosa and nasal breathing25,26. Therefore, it is necessary to establish correlations that can be applied to predict concentrations of PAHs in sediments for cutting costs and saving time in laboratory analysis27,28.

In recent literatures, significantly positive correlations between the total concentration of PAHs (CƩPAHs) and the content of total organic carbon (foc) in sediments were established to predict CƩPAHs17,29,30,31, built on the premise that the distribution of PAHs between sediments and water is largely depended on the partitioning of PAHs into sediment organic matter32. However, our preliminary work indicated that CƩPAHs predicted using foc (Eq. 1) does not hold true for additional CƩPAHs and foc data of 233 global sediment samples (Fig. 1a, Table S2), presented by the low determination coefficients (R2 = 0.20) and the great percent sample deviation (SDEV = 771%). One possible reason for the insignificant correlation between CƩPAHs and foc when more data was introduced is that the difference in emissions of PAHs in various regions is ignored. Another possible reason is that the dependence of PAHs partitioning in sediment organic matter and their polarity is ignored4,32,33. Furthermore, nonlinear sorption of PAHs on sediments organic matter is also ignored34,35.

Intrinsic quantitative relationships between CƩPAHs and the concentrations of single PAHs congener were also established to predict sediment CƩPAHs in previous studies36,37,38,39. For example, the concentration of benzo(a)pyrene (CBaP)36,37, pyrene (CPyr)38 or acenaphthene (CAce)39 was suggested to predict CƩPAHs (Table S3). However, when relationships of CƩPAHs with CBaP (Eq. 2), CPyr (Eq. 3) and CAce (Eq. 4) were established using the additional sediment concentration data of PAHs from China (Table S4), it was found that the relationships were less significant with greater deviation (Eqs. 2–4). For example, R2 of the linear relationship between CƩPAHs and CAce (Eq. 4) reduced from 0.8239 to 0.49 (Eq. 4) with SDEV increased from 27%39 (Table S3) to 461% (Eq. 4), when sediment sample numbers (N) increased from 1039 (Table S3) to 754 (Eq. 4), respectively. A possible reason for these relationships (Eqs. 2–4) predicted with less accuracy is that the difference in emission factors (EFs) of PAHs congeners for various sources is ignored. For example, at the equivalent emission factors of the total PAHs (EFƩPAHs), which is 4.39 g t−1 for iron sintering and 4.51 g t−1 for gasoline combustion (Table 1), EF of Ace (Table 1) from iron sintering is 0.079 g t−1, about 2 orders of magnitude larger than that 0.00046 g t−1 of gasoline combustion40,41. Therefore, the concentrations of single PAHs congener cannot be used to accurately predict CƩPAHs in sediments on a large scale. The characteristic PAHs congeners in emission sources and in sediments should be explored to develop an accurate model for predicting CƩPAHs in sediments.

In this study, a multiple linear relationship between EFΣPAHs and the EFs of characteristic congeners was established by identifying characteristic PAHs congeners in emission sources. Moreover, another multiple linear relationship between CΣPAHs and the concentrations of characteristic congeners in sediments was established by identifying characteristic PAHs congeners in sediments. Finally, an accurate model for predicting CΣPAHs in sediments was established by exploring the correlation between the sediment concentrations and the emissions of characteristic PAHs congeners. The established model can cut costs and save time in PAHs analysis for risk assessing of PAHs in the sediment environment.

Result and discussion

Characteristic congeners of PAHs in emission

Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) and classifications for relative similarities42,43 of PAHs emission factors (Table S5) show that sixteen PAHs can be divided into four groups (Table 1, Fig. 2). The first subgroup is Nap (Table 1, Fig. 2) because of its highest EFs in most emission sources (Table S5). Acy is the second subgroup (Table 1, Fig. 2) with significant lower EFs than that of Nap but higher than other PAHs congeners in most emission sources (Table S5). The third subgroup comprises four 3-ring PAHs (Ace, Flo, Phe and Ant) and two 4-ring PAHs (Pyr and Flu) (Fig. 2, Table 1). In this subgroup, the EFs of Phe (EFPhe) has the best linear correlation with the total EFs of this subgroup, showing the maximum R2 of 0.98 (N = 15, p < 0.01) (Table 1). Thus, the total EFs of the third subgroup can be expressed by EFPhe with the largest degree of accuracy43,44. The last subgroup is composed of the other eight PAHs congeners (Fig. 2, Table 1), including 4-ring PAHs (BaA and Chr) and 5, 6-ring PAHs (BbF, BkF, BaP, IcdP, DahA and BghiP). The EFs of BaA (EFBaA) correlates best with the total EFs of the eight PAHs in this subgroup with the maximum R2 of 0.98 (N = 15, p < 0.01) (Table 1). This indicates that the total EFs of the last subgroup can be presented by EFBaA. Moreover, the total EFs of sixteen PAHs (EFƩPAHs) are well related with EFNap, EFAcy, EFPhe, and EFBaA in a multilinear relationship (Eq. 5 and Fig. 3), having R2 of 0.99, high F values of 5257, and low SDEV of 24%. Therefore, Nap, Acy, Phe, and BaA can be employed as characteristic congeners of sixteen PAHs in emission sources (Fig. 3).

Characteristic congeners of PAHs in sediments

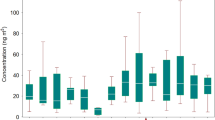

The HCA dendrogram for correlations of sixteen PAHs in sediments of China is shown in Fig. 4. When PAHs are classified into two groups, the first subgroup is composed of 2, 3-rings PAHs and two 4-rings PAHs (Table 2). In this subgroup, the concentration of Phe (CPhe) correlates best with the total concentration of the eight congeners with the maximum R2 of 0.83 (N = 754, p < 0.01) (Table 2). The other two 4-rings PAHs and 5, 6-rings PAHs are divided into the second subgroup (Table 2). In the second subgroup, the maximum value of R2 was found between the concentration of BaA (CBaA) and the total concentration of the eight congeners (R2 = 0.79, N = 754, p < 0.01) (Table 2). Thus, the total concentration of PAHs in two subgroups can be expressed by CPhe and CBaA with the largest degree of accuracy, respectively43,44. Relationship of CPhe and CBaA with CƩPAHs was established in Eq. (6). Similarly, when 16 PAHs were classified into three groups, the concentration of Nap (CNap), Phe (CPhe), and BaA (CBaA) correlate best with the total concentrations of congeners in corresponding subgroup (Table 2). Relationship of CNap, CPhe, and CBaA with CƩPAHs was established in Eq. (7). When sixteen PAHs were classified into four groups, CNap, CAcy, CPhe, and CBaA correlate best with the total concentrations of congeners in corresponding subgroup (Table 2). Relationship of CNap, CAcy, CPhe, and CBaA with CƩPAHs was established in Eq. (8). When sixteen PAHs were classified into five groups, CNap, CAcy, CPhe, CBaA, and the concentration of DahA (CDahA) correlate best with the total concentrations of congeners in corresponding subgroup (Table 2). Relationship of CNap, CAcy, CPhe, CBaA and CDahA with CƩPAHs was established in Eq. (9). Correlations between the calculated CƩPAHs (CƩPAHs(cal)) and the experimental value (CƩPAHs(exp)) are presented in Fig. 5. SDEV values between CƩPAHs(cal) and CƩPAHs(exp) in Fig. 5a–d were 124%, 75%, 35% and 37%, respectively. SDEV values decreased significantly from Fig. 5a–c, while almost remained constant from Fig. 5c, d. Intercepts in equations presented the same tendency to SDEV value (Fig. 5). CƩPAHs can’t be accurately predicted using two (Fig. 5a) or three congeners (Fig. 5b), especially when CƩPAHs in sediments lower than the intercepts in Eqs. (6–7). Four (Fig. 5c) or five congeners (Fig. 5d) can accurately predict CƩPAHs. However, more work needs to be done to complete the prediction of five congeners than four congeners. In summary, CƩPAHs can be well predicted from the concentration of Nap, Acy, Phe, and BaA using the linear relationship of Eq. (8) (Fig. 5c).

Fitted CƩPAHs(cal) values from two groups (a), three groups (b), four groups (c) and five groups (d) versus CƩPAHs(exp) values in sediments sampled in China. The y = x line (solid lines) indicates a 1:1 relationship between CƩPAHs(cal) and CƩPAHs(exp). Dashed lines in the plots indicate the SDEV values from the reference lines.

Prediction of total PAHs concentrations in sediments with characteristic PAHs congeners

With the established multiple linear relationship (Eq. 8), we found that the total PAHs concentrations (C∑PAHs) in sediments can be predicted from the concentrations of four characteristic congeners with high R2 but low SDEV value. Figure 5c shows that C∑PAHs(cal) are consistent with C∑PAHs(exp) in sediments sampled in China. Scatterplots of unstandardized residuals (the difference between CƩPAHs(cal) and CƩPAHs(exp)) with CNap, CAcy, CPhe or CBaA in sediments distributed regularly on both sides of the horizontal line and no obvious positive or negative trend existed (Fig. S1). This indicates the significant stability of the established linear relationship45. Furthermore, CƩPAHs(cal) also agreed well with CƩPAHs(exp) using additional concentration data (Table S6) in sediment samples from elsewhere around the globe (N = 691) (Fig. 6), suggesting that the relationship can be applied to predict CƩPAHs in sediments that are not only localized in China. Therefore, Nap, Acy, Phe, and BaA can be also employed as characteristic congeners of sixteen PAHs in sediments.

The same characteristic congeners observed for PAHs in sediments and in emission sources indicates that the concentration of PAHs in sediments are largely depended on their emission, which was consistent with the reported results46,47,48. In previous studies17,29,30,31, PAHs emissions were not involved in the relationship of predicting PAHs concentration in sediments using foc (Eq. 1), which does not hold true in some cases. For example, for a given foc, CƩPAHs in sediments can vary by 1–3 orders of magnitude (Fig. 1a) because of the difference in PAHs emissions in various regions. For another example, although the mean foc (6.4%) in sediments from the upper reach of Huaihe River50 was higher than that in sediments from the lower reach of Huaihe River (foc = 4.1%)51, CΣPAHs in sediments from the lower reach of Huaihe River (mean value = 1721.7 µg kg−1)50 were higher than that from the upper reach (mean value = 400.5 µg kg−1)51. This can be attributed to the higher emission intensity of PAHs in lower reach of Huaihe River region than that in the upper reach region41,52,53. Moreover, a significantly positive correlation between mean concentrations of thirteen PAHs (except for Nap, Acy, and Ace) in sediment samples derived from globe (N = 1445) and their mean EFs in fifteen emission divisions was also observed (Fig. S2), indicating that the concentration of PAHs in sediments also mainly depends on the PAHs emission. The deviation of Nap, Acy, and Ace from the linear relationship in Fig. S2 can be attributed to their relatively low logKow but high Sw (Table S1), making them not be readily adsorbed by organic matters in sediments but tend to be more readily dissolved in water48.

Relationship between PAHs concentrations in sediments and EFs in emission sources

Significance of multicomponent coefficients in Eqs. (5) and (8) were less than 0.05 (p < 0.05), which are statistically significant. However, significance of intercept in Eq. (5) was greater than 0.05 (p > 0.05), which is statistically insignificant. The significant intercept (p < 0.05) in Eq. (8) can be assigned to background concentrations of PAHs in sediments54,55. Moreover, significantly positively linear relationships of the multicomponent coefficients in Eq. (5) and that in Eq. (8) with the logKow of four characteristic congeners were observed (Fig. 7a). Interestingly, the coefficient of characteristic congeners with larger logKow, such as BaA, in Eq. (8) are higher than that in Eq. (5) (Fig. 7a). This could be attributed to the influence of sorption of PAHs in sediments and their biodegradation in the environment. For PAHs with larger logKow, they tend to be more readily adsorbed in sediments organic matter by partitioning than the PAHs with smaller logKow56,57. Meanwhile, PAHs congeners with relatively low logKow tend to be more readily degraded than those with relatively high logKow58,59, presented by the positively linear relationship of PAHs logKow with their biodegradation half-life (Fig. S3). Therefore, a positively linear relationship between the ratio of multicomponents coefficient from the multiple linear relationship in sediments (Eq. 8) to that from the multiple linear relationship in emission sources (Eq. 5) and the logKow of four PAHs congeners can be observed in Fig. 7b. This suggests that the distribution of PAHs in sediments could also be dependent on their environmental behaviors including sorption and biodegradation in addition to their emissions. In previous study46, significant linear relationships between the concentrations of sixteen PAHs in sediments (CPAHs) with their emissions (EPAHs) were established (Eq. 10). Moreover, positive and negative relationships of K (Eq. 11) and L (Eq. 12) with logKow were established, respectively.

In this study, a multilinear relationship of CΣPAHs with CNap, CAcy, CPhe, and CBaA was established (Eq. 8). The concentration of four characteristic PAHs congeners in sediments can be calculated using their emissions and logKow (Eqs. 10–12). Therefore, CΣPAHs in sediments can be predicted using the emissions and logKow of four characteristic PAHs congeners, in which logKow can be accounted for PAHs partition ability. Mean C∑PAHs(exp) in surface sediments sampled in investigated provinces of China (N = 30) and other countries (N = 21) versus C∑PAHs(cal) predicted using EPAHs (Tables S7 and S8) and logKow of four characteristic PAHs congeners is presented in Fig. 8. The SDEV value between C∑PAHs(exp) and C∑PAHs(cal) is 54%, suggesting that C∑PAHs(cal) are well consistent with C∑PAHs(exp). Therefore, the established model in this study can be used to predict CΣPAHs in sediments with high accuracy, resulting in decreasing cost of laboratory analysis.

Fitted CƩPAHs(cal) using EPAHs and logKow of four characteristic PAHs congeners versus CƩPAHs(exp) in sediments sampled in investigated provinces of China and other countries. The y = x line (solid line) indicates a 1:1 relationship between CƩPAHs(cal) and CƩPAHs(exp). Dashed lines in plots indicate the SDEV values from the reference lines.

The correlations that have been previously described in literature of CƩPAHs with CBaP36,37, CPyr38 or CAce39 could be attributed to the PAHs emissions in the investigated region from one emission source or emission sources with similar EFs (Table 1). For example, PAHs in sediment samples of Norway were mainly from manufactured gas plants and aluminum smelters38, in which Pyr is the dominant congener with relatively high EFs40,41,52. However, the multiple linear relationship established herein (Eq. 6) gives a useful way to predict the CƩPAHs in sediments using PAHs emissions emitted from major emission sources around the world as seen by the good correlation with the large and diverse sample size. Therefore, this relationship would be valuable for predicting total PAHs concentrations and assessing their risks in sediments.

Conclusion and perspectives

A multiple linear relationship of C∑PAHs with CNap, CAcy, CPhe, and CBaA in sediments was established employing the reported data in the past 30 years. This suggested the selected four PAHs congeners, including Nap, Acy, Phe, and BaA, are the characteristic congeners in sediments. Moreover, the multiple linear relationship of EF∑PAHs with the EFs of the four congeners was also developed. The same characteristic congeners observed for PAHs in sediments and in emission sources indicates that the concentration of PAHs in sediments are largely dependent on their emissions. Additionally, the ratio of multicomponents coefficient from the multiple linear relationship in sediments to that from the multiple linear relationship in emission sources correlated positively with logKow of the four congeners. Therefore, a model for predicting CΣPAHs in sediments was established using the emissions and logKow of four PAHs congeners. The SDEV value between C∑PAHs(exp) and C∑PAHs(cal) was 54%, suggesting the established model can accurately predict CΣPAHs in sediments.

Although the relationship established in this study could be used to predict total sixteen PAHs concentration in surface sediments of China and other countries, the application of this method for predicting additional PAHs in sediment, such as alkylated-PAHs, needs further verified.

Methodology

Literature search

Concentration data of sixteen parent PAHs (Table S4 and Table S6) in global bottom sediments of fresh water reported in the past 30 years were collected. A systematic literature retrieval was performed using the ISI Web of Science database, Google®Scholar, WanFang Data of E-Resources and China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database including master/doctoral dissertation using the terms of “polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons” or “PAHs” and “sediment/sediments” as the primary keywords60. Articles were then examined individually to ensure that the duplicates and irrelevant articles were excluded from further analysis. In addition, articles without individual PAHs concentration data and/or articles that did not report QA/QC procedure and limits of detection (LODs) were also excluded from further analysis60. In order to perform the required comparisons in this study, it was assumed that there were no significant differences in the sampling process and analysis among the investigating groups/laboratories60,61. In total, 22,349 individual PAH concentrations from 1445 sediments samples were collected from 1184 publications and then used for meta-analysis (Table S4 and Table S6).

PAHs emissions

According to the previous study40, PAHs emissions in globe was primarily emitted from coking production, petroleum refineries, domestic and industrial coal combustion, straw and firewood burning, iron-steel industry, transport petroleum, and primary Al production, which accounting for more than 92% of all source contributions. Therefore, PAHs emissions from these nine sources were calculated using a previously reported approach for analysis40,41. Emission factors (EFs, g t−1) of sixteen PAHs from above nine emission sources were summarized in Table S5. Provincial and national PAHs emissions (EPAHs, t a−1) were calculated using Eq. (13)40,41,52:

where i, j, and k represent each PAH congener, sources, and technology, respectively.

EF (g t−1) is the emission factor of the PAHs congener i (Table S5). X is the fraction of the activity rate contributed by a given technology j, which was calculated using the technology split method40,41,52. Activity data (A, 104 t a−1) in source j, from China, were obtained directly from China Statistical Yearbook (2001–2018) and China Energy Statistical Yearbook (2001–2018), edited by National Bureau of Statistics40. The data from other countries were derived from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, International Yearbook of Industrial Statistics (2004–2018), and International Energy Agency World Energy Statistics and Balances40.

For the technology splitting approach, six sources (coking production, industrial coal combustion, indoor straw and firewood burning, iron-steel industry, and primary Al production) were divided into two or three divisions with or without different emission mitigation measures40,41. For the remaining three sources, fixed EFPAHs without divisions were used40,41. The time-dependent fractions of technology divisions were calculated using a series of S-shaped curves (Eq. 14, Table S9).

where X0 and Xf are initial and final fractions of a certain technology division, respectively. t0 is the start time of technology transition, and s is a rate. The Xf, X0, t0, and s were illustrated in Table S940.

Data analysis

11,937 individual concentrations data from 754 sediments sampled from China were used to establish the relationship between CƩPAHs and the concentration of selected congeners in sediments (Table S4). To validate the established relationship, 10,412 individual concentrations data from 691 sediments sampled from globe (excluding China) were used as a test set (Table S6). Concentrations that were reported to be below the method LODs were assigned half the value of the reported LODs61,62. Concentration unit of PAHs were set uniformly to micrograms per kilogram (µg kg−1) of dry weight. Prior to statistical analysis, a histogram with normal curve was viewed and a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test were performed to verify the normality of variables38. If the significance (p) is greater than 0.05 (p > 0.05), it can be judged that the variables are normal38. Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) and classifications were performed using the SPSS Statistics 19.0 software (Version 19.0, Chicago, IL, USA) according to relative similarities of EFs in emission sources and concentrations in sediments of sixteen PAHs42,43. Statistical analysis, including linear and multilinear regression, were also performed using the SPSS Statistics 19.0 with a critical significance (p) up to 0.05 to check significance. Provincial or national PAHs emissions combined with their observed C∑PAHs in surface sediments were used to evaluate the established model between C∑PAHs and emissions of the four characteristic congeners. Moreover, C∑PAHs in surface sediments sampled in the same province or nation at the same year were expressed by the geometric mean value63.

Percent sample deviation (SDEV, Eq. (15)) was calculated based on the relative error between the experimental values (Cexp) and the calculated value (Ccal)64. In addition to the SDEV, significance of F test (p) and correlation coefficient (R2) were used to evaluate the goodness of the fitting and the established correlations by regression analysis64.

where N is the number of experimental values and k is the number of predictors for linear regression.

References

Haritash, A. K. & Kaushik, C. P. Biodegradation aspects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 169, 1–15 (2009).

Zheng, X. et al. Characterizing particulate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions from diesel vehicles using a portable emissions measurement system. Sci. Rep. 7, 10058 (2017).

Syed, J. H. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Chinese forest soils: Profile composition, spatial variations and source apportionment. Sci. Rep. 7, 2692 (2017).

Agarwal, T., Khillare, P. S. & Shridhar, V. Pattern, sources and toxic potential of PAHs in the agricultural soils of Delhi, India. J. Hazard. Mater. 163, 1033–1039 (2009).

Chen, W. H., Hsieh, M. T., You, J. Y., Quadir, A. & Lee, C. L. Temporal and vertical variations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon at low elevations in an industrial city of southern Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 11, 3453 (2021).

Vu, V. T., Lee, B. K., Kim, J. T., Lee, C. H. & Kim, I. H. Assessment of carcinogenic risk due to inhalation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in PM10 from an industrial city: A Korean case-study. J. Hazard. Mater. 189, 349–356 (2011).

Li, S. Y., Tao, Y. Q., Yao, S. C. & Xue, B. Distribution, sources, and risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the surface sediments from 28 lakes in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River region, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 4812–4825 (2016).

Bergamasco, A. et al. Composition, distribution, and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments of the Gulf of Milazzo (Mediterranean Sea, Italy). Polycycl. Aromat. Hydrocarb. 34, 397–424 (2014).

Portet-Koltalo, F. et al. Bioaccessibility of polycyclic aromatic compounds (PAHs, PCBs) and trace elements: Influencing factors and determination in a river sediment core. J. Hazard. Mater. 384, 121499 (2020).

Doong, R. A. & Lin, Y. T. Characterization and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminations in surface sediment and water from Gao-ping River, Taiwan. Water Res. 38, 1733–1744 (2004).

Chen, Y. Y., Zhu, L. Z. & Zhou, R. B. Characterization and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in surface water and sediment from Qiantang River, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 141, 148–155 (2007).

Guo, W. et al. Distribution, partitioning and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Daliao River water system in dry season, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 164, 1379–1385 (2009).

Maskaoui, K., Zhou, J. L., Hong, H. S. & Zhang, Z. L. Contamination by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Jiulong River Estuary and Western Xiamen Sea, China. Environ. Pollut. 118, 109–122 (2002).

Tian, Y. Z., Li, W. H., Shi, G. L., Feng, Y. C. & Wang, Y. Q. Relationships between PAHs and PCBs, and quantitative source apportionment of PAHs toxicity in sediments from Fenhe reservoir and watershed. J. Hazard. Mater. 248–249, 89–96 (2013).

Adhikari, P., Maiti, K., Overton, E., Rosenheim, B. & Marx, B. Distributions and accumulation rates of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the northern Gulf of Mexico sediments. Environ. Pollut. 212, 413–423 (2016).

Cardoso, F. D., Dauner, A. L. L. & Martins, C. C. Critical and comparative appraisal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments and suspended particulate material from a large South American subtropical estuary. Environ. Pollut. 214, 219–229 (2016).

Montuori, P. et al. Distribution, sources and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water and sediments from Tiber River and estuary, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 566–567, 1254–1267 (2016).

Xu, E. G., Bui, C., Lamerdin, C. & Schlenk, D. Spatial and temporal assessment of environmental contaminants in water, sediments and fish of the Salton Sea and its two primary tributaries, California, USA, from 2002 to 2012. Sci. Total Environ. 559, 130–140 (2016).

Martinez, E., Gros, M., Lacorte, S. & Barceló, D. Simplified procedures for the analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water, sediments and mussels. J. Chromatogr. A 1047, 181–188 (2004).

Leite, N. F., Peralta-Zamora, P. & Grassi, M. T. Multifactorial optimization approach for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in river sediments by gas chromatography–quadrupole ion trap selected ion storage mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1192, 273–281 (2008).

Pena-Abaurrea, M., Ye, F., Blasco, J. & Ramos, L. Evaluation of comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-time-of-flight-mass spectrometry for the analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments. J. Chromatogr. A 1256, 222–231 (2012).

Song, Y. F., Jing, X., Fleischmann, S. & Wilke, B. M. Comparative study of extraction methods for the determination of PAHs from contaminated soils and sediments. Chemosphere 48, 993–1001 (2002).

Shamsipur, M. & Hassan, J. A novel miniaturized homogenous liquid–liquid solvent extraction-high performance liquid chromatographic-fluorescence method for determination of ultra traces of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediment samples. J. Chromatogr. A 1217, 4877–4882 (2010).

Frenna, S., Mazzola, A., Orecchio, S. & Tuzzolino, N. Comparison of different methods for extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from Sicilian (Italy) coastal area sediments. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185, 5551–5562 (2013).

Liu, Y., Kong, X., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Y. Analysis on the purification technology of dichloromethane waste gas. Appl. Chem. Ind. 50, 1409–1413 (2021).

Cooper, G. S., Scott, C. S. & Bale, A. S. Insights from epidemiology into dichloromethane and cancer risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 3380–3398 (2011).

Owen, C. et al. Screening for PAHs by fluorescence spectroscopy: A comparison of calibrations. Chemosphere 31, 3345–3356 (1995).

Peterson, G. S., Axler, R. P., Lodge, K. B., Schuldt, J. & Crane, J. Evaluation of a fluorometric screening method for predicting total PAH concentrations in contaminated sediments. Environ. Monit. Assess. 78, 111–129 (2002).

Simpson, C. D., Mosi, A. A., Cullen, W. R. & Reimer, K. J. Composition and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contamination in surficial marine sediments from Kitimat Harbor, Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 181, 265–278 (1996).

Sun, J. et al. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Henan Reach of the Yellow River, Middle China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 72, 1614–1624 (2009).

Arienzo, M. et al. Characterization and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the sediments of gulf of Pozzuoli (Campania, Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 124, 480–487 (2017).

Chiou, C. T., McGroddy, S. E. & Kile, D. E. Partition characteristics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on soils and sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 264–269 (1998).

Bucheli, T. D., Blum, F. & Desaules, A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, black carbon, and molecular markers in soils of Switzerland. Chemosphere 56, 1061–1076 (2004).

Cornelissen, G., Gustafsson, O. & Bucheli, T. D. Extensive sorption of organic compounds to black carbon, coal, and kerogen in sediments and soils: Mechanisms and consequences for distribution, bioaccumulation, and biodegradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 6881–6895 (2005).

Jin, J. et al. Characterization and phenanthrene sorption of natural and pyrogenic organic matter fractions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 2635–2642 (2017).

Zhu, L. Z., Chen, B. L., Shen, H. X. & Wang, J. Pollution status quo and risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface water of Hangzhon City, China. Environ. Sci. 23, 485–489 (2003) ((in Chinese)).

Luo, S. Study on the organic pollution status and source apportionment of PAHs in water and sediment of HongFeng Lake. Master. Guizhou Normal University, pp. 87 (2005).

Arp, H., Azzolina, N., Cornelissen, G. & Hawthorne, S. Predicting pore water EPA-34 PAH concentrations and toxicity in pyrogenic-impacted sediments using pyrene content. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 5139–5146 (2011).

Qian, X., Liang, B., Fu, W., Liu, X. & Cui, B. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface sediments from the intertidal zone of Bohai Bay, Northeast China: Spatial distribution, composition, sources and ecological risk assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 112, 349–358 (2016).

Shen, H. et al. Global atmospheric emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from 1960 to 2008 and future predictions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 6415–6424 (2013).

Li, B. et al. An improved gridded polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emission inventory for the lower reaches of the Yangtze River Delta region from 2001 to 2015 using satellite data. J. Hazard. Mater. 360, 329–339 (2018).

Sørlie, T., Perou, C. M. & Tibshirani, R. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. PNAS 98, 10869–10874 (2001).

Oh, J. E., Gullett, B., Ryan, S. & Touati, A. Mechanistic relationships among PCDDs/Fs, PCNs, PAHs, CIPhs, and CIBzs in municipal waste incineration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 4705–4710 (2007).

Liu, G. et al. Identification of indicator congeners and evaluation of emission pattern of polychlorinated naphthalenes in industrial stack gas emissions by statistical analyses. Chemosphere 118, 194–200 (2015).

Zhang, W. T. & Dong, W. Chapter 6 - Advanced course of SPSS statistical analysis, Beijing, Higher Education Press, pp 97–108 (2013).

Wang, W. W., Qu, X. L., Lin, D. H. & Yang, K. Octanol-water partition coefficient (logKow) dependent movement and time lagging of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from emission sources to lake sediments: A case study of Taihu Lake, China. Environ. Pollut. 288, 117709 (2021).

Li, R., Hua, P., Zhang, J. & Krebs, P. A decline in the concentration of PAHs in Elbe River suspended sediments in response to a source change. Sci. Total Environ. 663, 438–446 (2019).

Moeckel, C., Monteith, D. T., Llewellyn, N. R., Henrys, P. A. & Pereira, M. G. Relationship between the concentrations of dissolved organic matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a typical U.K. upland stream. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 130–138 (2014).

Feng, J., Zhai, M. & Sun, J. Distribution and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in sediment from the upper reach of Huaihe River, East China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 19, 1097–1106 (2012).

Zhang, J., Liu, G., Wang, R. & Liu, J. Distribution and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in bank soils and river sediments from the middle reaches of the Huaihe River, China. CSAWAC 43, 1115–1266 (2015).

Zheng, X. Contamination and release kinetics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (Subei Section). China Mining University (2010).

Li, B. et al. New method for improving spatial allocation accuracy of industrial energy consumption and implications for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4326–4334 (2019).

Xu, S. S., Liu, W. X. & Tao, S. Emission of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 702–708 (2006).

Witt, G. & Trost, E. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in sediments of the Baltic Sea and of the German coastal waters. Chemosphere 38, 1603–1614 (1999).

Viguri, J., Verde, J. & Irabien, A. Environmental assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface sediments of the Santander Bay, Northern Spain. Chemosphere 48, 157–165 (2002).

Replinger, S., Katka, S., Toll, J., Church, B. & Saban, L. Recommendations for the derivation and use of biota-sediment bioaccumulation models for carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Integr. Environ. Asses. 13, 1060–1071 (2017).

Maletić, S. P., Beljin, J. M., Rončević, S. D., Grgić, M. G. & Dalmacija, B. D. State of the art and future challenges for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is sediments: sources, fate, bioavailability and remediation techniques. J. Hazard. Mater. 365, 467–482 (2019).

Bacosa, H. P. & Inoue, C. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) biodegradation potential and diversity of microbial consortia enriched from tsunami sediments in Miyagi, Japan. J. Hazard. Mater. 283, 689–697 (2015).

Johnsen, A. R., Wick, L. Y. & Harms, H. Principles of microbial PAH-degradation in soil. Environ. Pollut. 133, 71–84 (2005).

Bu, Q., Wang, B., Huang, J., Deng, S. & Yu, G. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the aquatic environment in China: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 262, 189–211 (2013).

Ma, W. L. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Chinese surface soil: occurrence and distribution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 4190–4200 (2015).

Cai, Q. Y., Mo, C. H., Wu, Q. T., Katsoyiannis, A. & Zeng, Q. Y. The status of soil contamination by semivolatile organic chemicals (SVOCs) in China: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 389, 209–224 (2008).

Yu, H. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface freshwaters from the seven main river basins of China: Spatial distribution, source apportionment, and potential risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 752, 141764 (2021).

Crittenden, J. C. et al. Correlation of aqueous-phase adsorption isotherms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 2926–2933 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported partly by Scientific and Technological Basic Work of China (2014FY120604), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0207001) and the NSF of China (21621005 and 21777138).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.W.: writing-original draft. H.X.: writing-review and editing. X.Q.: writing-review and editing. D.L.: writing-review and editing. K.Y.: supervision, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Xu, H., Qu, X. et al. Predicting the total PAHs concentrations in sediments from selected congeners using a multiple linear relationship. Sci Rep 12, 3334 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07312-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07312-2

This article is cited by

-

Assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surficial sediments of northern Red Sea ports: sources, distribution, and ecotoxicological risk

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2025)

-

Source Apportionment of Hydrocarbons in Ghana's Coastal Sediments: Utilizing Hydrocarbons Ratios and Advanced Statistical Methods

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2024)