Abstract

Metal artefacts degrade clinical image quality which decreases the confidence of using computed tomography (CT) for the delineation of key structures for treatment planning and leads to dose errors in affected areas. In this work, we investigated accuracy of doses computed by the Eclipse treatment planning system near and inside metallic elements for two different computation algorithms. An impact of CT metal artefact reduction methods on the resulting calculated doses has also been assessed. A water phantom including Gafchromic film and metal inserts was irradiated (max dose 5 Gy) using a 6 MV photon beam. Three materials were tested: titanium, alloy 600, and tungsten. The phantom CT images were obtained with the pseudo-monoenergetic reconstruction (PMR) and the iterative metal artefact reduction (iMAR). Image sets were used for dose calculation using an Eclipse treatment planning station (TPS). Monte Carlo (MC) simulations were used to predict the true dose distribution in the phantom allowing for comparison with doses measured by film and calculated by TPS. Measured and simulated percentage depth doses (PDDs) were not statistically different (p > 0.618). Regional differences were observed at edges of metallic objects (max 8% difference). However, PDDs simulated with and without film were statistically different (p < 0.002). PDDs calculated by the Acuros XB algorithm based on the dose-to-medium approach best matched the MC reference regardless of the CT reconstruction methods and inserts used (p > 0.078). PDDs obtained using other algorithms significantly differ from the MC values (p < 0.011). The Acuros XB algorithm with a dose-to-medium approach provides reliable dose calculation in all metal regions when using the Varian system. The inability of the AAA algorithm to model backscatter dose significantly limits its clinical application in the presence of metal. No significant impact on the dose calculation was found for a range of metal artefact reduction strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An increasing number of patients with metallic implants are treated with radiotherapy and so it is important to better understand the impact of these elements on the treatment process. The proximity of a metal object causes streaking image artefacts observed in the computed tomography (CT) scans deteriorating diagnostic quality and ability to confidently delineate structures such as organs at risk and tumours1,2,3. Misrepresentation of CT numbers can also cause errors in calculated linear attenuation coefficients leading to significant errors in dose calculation in affected areas4. The simple density override method, covering the affected area by contour with manually corrected CT numbers, can reduce the dose calculation error5. However, this method doesn’t improve visualization of areas affected by artefacts, which is important for accurate delineation of anatomical structures. Several metal artefact reduction methods were proposed, such as the iterative metal artefact reduction (iMAR) algorithm6,7,8, the dual-energy method (enabling the pseudo-monoenergetic reconstruction (PMR) of CT images created for specified photon energy)9, and a unique technique based on the use of megavoltage CT imaging on the tomotherapy units10,11. Combinations of PMR and iMAR methods have been previously investigated and demonstrates significant reduction of metal artefacts and low CT number errors observed in the vicinity of dense materials12. Besides errors due to the presence of artefacts, there is also doubt related to the precision of dose calculation in the presence of high-density materials13. These metal elements lead to higher beam attenuations and reveal interface phenomena caused by backscatter radiation14. For precise dose calculation, these perturbations have to be accounted for. Currently, only algorithms utilising the medium for dose transport and calculation can model this accurately15. However, there is still a lack of comprehensive analysis of different metal artefact reduction methods and their impact on algorithms used for dose calculations. Many authors verified the impact of metals on the radiotherapy process, however, most of them used only one metal which can be insufficient for understanding the behaviour of the algorithms and their limitations16,17,18. Our work focused on obtaining a Monte Carlo validated simulation of three metals with different, clinically relevant densities and comparing them with different dose algorithm calculations using a range of MAR methods. In particular, we assess: (1) the accuracy of dose computation using Acuros XB and AAA (analytical anisotropic algorithm) calculation algorithms near and inside the metal structures, and (2) the impact of different methods for metal artefact reduction in CT on the accuracy of doses computed through these algorithms.

Materials and methods

Dose measurements

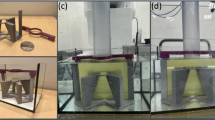

A 25 × 25 × 30 cm3 water phantom with holder for Gafchromic film and metal inserts was fabricated (Fig. 1a). A 3D printed holder was designed to allow for the placement of the Gafchromic film parallel to the beam axis and to fix the removable cylindrical inserts at a precisely defined depth. The distance between the top edge of the Gafchromic film and the center of the insert was 5 cm.

Specific information about phantom components:

-

(1)

Phantom holder: Original Prusa i3 MK3S + 3D printer (Prusa Research; Prague, Czech Republic) was used to print the phantom holder in fused deposition modeling technology with polylactic acid filament19,20.

-

(2)

Inserts: The cylindrical inserts (2.8 cm diameter and 7 cm length), consisting of two halves (Fig. 1b), were made from three high-density materials: titanium, alloy 600, and tungsten with physical densities of 4.5, 8.5, and 19.4 g/cm3, respectively12. The dimensions of inserts allowed to position them in both dosimetric and CT calibration (Virtual Water™, described below) phantoms.

-

(3)

Film: Self-evoking EBT3 Gafchromic films (Ashland Inc., Wilmington, Delaware, USA). The films are made of an active layer with a thickness of 28 μm, located between two layers of matte-polyester substrates with a thickness of 125 μm. These films allow to measure the doses (optimal range from 0.2 to 10 Gy) obtained by radiation beams with energies ranging from 100 to 18 MeV. The film`s response is independent of temperature, atmospheric pressure, and the direction of the irradiation beam21,22. To avoid delamination and the water immersion effect, whole EBT3 sheets (20.3 cm × 25.4 cm) were placed in the 3D printed watertight holder.

The phantom including EBT3 film insert was filled with water up to the top edge of the film (Fig. 1a) and positioned on the accelerator couch. The source to phantom water surface distance, SPD, was 100 cm for all measurements. Central-axis percentage depth doses (PDD) were measured and simulated for a 6 MV photon beam produced by the TrueBeam accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, USA). Films were irradiated with a dose of 5 Gy defined at the point of maximum dose located at 15 mm below water surface. The beam field size was 10 cm × 10 cm oriented perpendicular to the water surface and the central axis (CAX) of the beam was in the middle of the film.

For the dose calibration curve, EBT3 film was cut into nine pieces (3 cm × 3 cm) and irradiated with a photon beam (10 cm × 10 cm, 6 MV) in ranges from 1 to 10 Gy.

The films were scanned 30 h after being irradiated using the Epson Perfection 750 Pro scanner (Seiko Epson Corporation, Japan) with the following parameters: no color correction, transmission mode, portrait orientation, 48-bit Red–Green–Blue (RGB)23. The scan resolution was 72 dpi for calibration and measurements. Scans were then analysed using Film Analyze 1.8 (PTW Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany; single red channel analysis from RGB).

Dose calculations

The phantom images were acquired using a Somatom Definition AS scanner (Siemens Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany). Two sets of CT images were obtained: (1) standard CT pelvis protocol (120 kV, 270 mAs, 0.6 pitch, 64 × 0.6 mm acquisition, 3 mm slice thickness, 2.0 mm increment, kernel B30s, extended CT scale) and (2) a dual-energy mode based on the two consecutive scan technique (first/second scan: 80 kV, 540 mAs/140 kV, 128 mAs; 0.6 pitch, 64 × 0.6 mm acquisition, 3 mm slice thickness, 2.0 mm increment, kernel B30f., extended CT scale) and used to obtain 70 and 130 keV PMR sets. The standard CT and 70 and 130 keV PMRs were reconstructed twice for each insert: once with and once without the iMAR algorithm (Siemens Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany) (Fig. 2).

Eclipse v.16.0 (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, USA) treatment planning system (TPS) was used in the study. The doses for each plan (each CT reconstruction) were normalised to the maximum depth and calculated by two available options: Acuros XB v.16.1.0 and AAA (i.e., analytical anisotropic algorithm) v.16.1.0 algorithms. In the case of Acuros XB calculations, two approaches: dose-to-medium and dose-to-water were considered. AAA calculations were based on CT density calculated by CT scanner and real CT value estimated from density. The spatial resolution of 1 mm was used for all calculations.

Six energy-dependent conversion curves (i.e., for each energy of CT reconstruction and for each class of calculation algorithm) were prepared for dose calculations. The curves were obtained using Virtual Water™ phantom (Gammex RMI, Middleton, WI, USA), with various inserts and different tissue densities12. The Virtual Water™ phantom was scanned using the same parameters as for the water phantom. Images were reconstructed for standard CT, 70 keV PMR, and 130 keV PMR series.

The segment high-density material option, available in the Eclipse TPS, was used for the insert contouring purposes. This tool finds and outlines structures with mass densities larger than 3 g/cm3. For the AAA algorithm, three energy-dependent CT numbers to electron density conversion curves relative to water were obtained. The whole range of CT numbers reconstructed in the insert during imaging was used for dose calculation by the AAA approach based on CT density. The real CT approach, used for dose calculation, manually overrides the value of the CT number with the mean value from the whole range of CT numbers detected in the insert. Conversion curves were also calculated for Acuros XB. The Acuros XB-13.5 material table was used for the Acuros material assignment including titanium alloy (titanium insert), stainless steel (alloy 600), and gold (tungsten). Tungsten material is not currently available for Acuros XB, and gold was used instead due to its comparable density (19.3 g/cm3 and 19.4 g/cm3 for gold and tungsten respectively).

Monte Carlo simulations

The Geant4 toolkit v.10.05.p01 was used for the Monte Carlo (MC) simulation of the dose distribution in our phantom for each insert (parallel computations, 5 dual Xeon processors, 32 GB RAM each). As a primary generator, data from phase space files provided by Varian were used24. Fifty-five files for the 6 MV photon beam were used in total, each one was iterated twenty times. Two phantom configurations were modelled for dose calculations: (1) MCmea with the information of dose deposited in the film corresponding to the measurement condition in the water-filled phantom with the EBT3 film placed between the two halves of the insert, and (2) MCpla corresponding to dose calculation in Eclipse TPS without the film present. For MCpla, the information of dose deposition, unlike MCmea, was not collected for the film but in water and the insert. Simulations in both configurations were performed under the same conditions matching experimental irradiation conditions described earlier.

Data analysis

The PDDs obtained from direct measurements, MC simulations, and Eclipse TPS calculations were compared on depths ranging from 15 to 85 mm, where 0 mm corresponds to the water surface. In particular, the PDDs comparisons were made between: (1) experimental, measured (EBT3) versus simulated MCmea (validation of MC simulated PDD), (2) MCmea versus MCpla (influence of film on PDD) and (3) MCpla versus Eclipse TPS (comparison of MC simulated and TPS calculated PDDs for different algorithms and for different reconstruction methods).

The comparison was made in five regions:

-

1.

water in front of the insert (15–34 mm),

-

2.

input edge of the insert ± 2 mm (34–38 mm),

-

3.

the insert (38–62 mm),

-

4.

output edge of the insert ± 2 mm (62–66 mm),

-

5.

water behind the insert (66–85 mm).

Mean dose differences were calculated for all regions and PDDs. Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Pearson tests were used to test differences between means and correlations with a 0.05 significance level.

Results

EBT3 film measurements versus MCmea comparison

Measured PDDs agree well with those simulated for every insert (Fig. 3) with mean PDD values strongly correlated and not statistically different (p > 0.618, R > 0.998) (Table 1). Regional analysis show that the highest differences between measured and simulated doses were observed in the regions of insert edges. The maximum difference was 8% and was detected for the input edge of the tungsten insert (Fig. 3). The highest mean differences were seen on the input (3%) and output (− 3%) edges of alloy 600 insert (Table 1). In other regions, the maximum differences were within ± 2%, and the mean differences were lower than 1% for every insert.

MCmea versus MCpla comparison

The PDDs simulated for measurement condition, MCmea, significantly differ from those simulated for TPS condition, MCpla (p < 0.002) (Fig. 4a). The PDD values in the insert region for MCpla (Fig. 4c) were on average lower by 23% (titanium), 26% (alloy 600), and 37% (tungsten) than corresponding MCmea values (Fig. 4b). In the region behind the insert, PDDs from MCpla were on average lower by 4% (titanium), 7% (alloy 600), and 12% (tungsten) than PDDs from MCmea.

(a) The comparison of PDDs obtained from Monte Carlo simulations performed for measurement (MCmea) and TPS conditions (MCpla) for titanium, alloy 600, and tungsten inserts. Visualisation of the insert geometry, (b) two halves of the grey circle with a film gap between them (MCmea conditions) and (c) solid grey circle without film gap (MCpla conditions). The red arrows visible in (b) and (c) represent the radiation beam.

MCpla versus TPS comparison

The best match to the MCpla PDDs was observed for the PDDs calculated by the Acuros XB algorithm based on the dose-to-medium approach (AXBDM) (Fig. 5). PDDs obtained from AXBDM calculations were similar to MCpla PDDs regardless of the CT reconstruction methods and inserts used (p > 0.078, R > 0.987) (Table 2). In contrast, PDDs obtained using other algorithms significantly differ from the MCpla PDD (p < 0.011).

The PDDs calculated by the Acuros XB algorithm based on the dose-to-water approach (AXBDW) was grossly overestimated in the insert region. The mean dose differences between the AXBDW and the MCpla PDDs in this region, depending on CT reconstruction mode, ranged from 43.6 to 45.0% for titanium, 43.0 to 45.6% for alloy 600, and 61.1 to 62.5% for tungsten. In the water regions (both in front and behind the inserts) the mean dose differences between AXBDW and the MCpla PDDs were lower than 2% for each CT reconstruction mode. The PDDs obtained from AAA calculations are more comparable to the MCpla for the true density (AAATD) than for the CT density (AAACT) based approach (Fig. 5). In the region in front of the insert, both approaches of AAA dose calculations agree with MCpla (differences < 2%). In the input/output edge of the insert due to lack of backscattered radiation, the differences between MCpla simulation and doses calculated by both AAA methods were, respectively, up to 10% for titanium, 15% for alloy 600, and 50% for tungsten. In the region behind the insert better agreement to MCpla was observed for AAATD than for AAACT. The mean differences for AAATD versus MCpla and AAACT versus MCpla were, respectively, up to 1% and 3.5% for titanium; 2% and 10% for alloy 600; and 7.5% and 36% for tungsten. In the insert region, the mean differences between AAATD versus MCpla were lower than AAACT versus MCpla and were, respectively, up to 11% and 12% for titanium; 9% and 15% for alloy 600; and 6% and 25% for tungsten.

Figure 6 shows the differences between MCpla and AXBDM PDDs obtained from calculations on different CT reconstructions for titanium, alloy 600, and tungsten inserts.

The highest differences between the MCpla and the AXBDM PDDs related to different CT reconstructions were observed at insert edges and they ranged from 4 to − 2% for titanium, 16% to − 9.5% for alloy 600, and 16% to − 15% for tungsten (Fig. 6). For the input edge regions standard deviations ranged from 1.5 to 2.0% for titanium, 3.6 to 8.9% for alloy 600, and 11.4 to 17.3% for tungsten (Table 2). In regions in-front and behind the insert, differences between the MCpla and the AXBDM PDDs were up to 2% (Fig. 6). The differences in the insert region depended on the density of the insert and were the lowest (up to 3%) for the titanium (4.5 g/cm3) and the highest (up to 12%) for the tungsten (19.4 g/cm3). Different CT reconstruction methods lead to differences between AXBDM PDDs in all compartments ranging up to 2%. Nevertheless, there is no clear superiority of one method of reconstruction over the others (Fig. 6).

All sets of PDD curves calculated using different algorithms, CT reconstructions and inserts are presented in a supplementary material.

Discussion

Several studies show that both algorithms (AAA and AXB) could accurately calculate the doses near the metal25,26,27. However, these studies focus specifically on spine SBRT (stereotactic body radiation therapy) treatment in the presence of titanium screws. Due to the relatively small dimensions of the screws and titanium density, the dose calculated in the tissues surrounding the screws is in line with measurements. Our results are in line with these observations, the doses calculated by AAA and AXB algorithms in the water near the titanium insert are close to MC simulations (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, there may be metal structures with a higher density than titanium in the patient body and geometries larger than screws used for spine stabilisation13,16,28. In general, to check accuracy between calculations and measurements, the ionising chambers or EBT films for in-axis dose measurements in front and behind the metal inserts and the perpendicularly oriented to the axis EBT films for profile measurements were used. Our study focused specifically on in-axis percentage depth dose measurements and calculations. In addition to previous studies, the EBT3 film placement in our phantom allows to simulate measurement conditions inside metal inserts. We recognise that the EBT3 films between the insert's halves resulted in measurements in a thin gap (< 0.3 mm) between parts of the insert filled by the film, rather than inside of the insert. Due to scanning modes used and the film thickness, the gap between the insert halves was not visible on the reconstructed CT images. Even with the smallest possible grid for dose calculation in TPS, the grid size was three times larger than the film thickness and the TPS calculations do not take into account the gap in the insert. Therefore, the measured doses by film were used only to compare to MC simulations for measurement conditions to prove the accuracy of MC simulations. The percentage depth doses obtained from MC simulation for TPS conditions (without the gap) were used as reference data for TPS calculations.

Analysing the accuracy of dose calculation through different algorithms shows the superiority of Acuros XB algorithm based on dose-to-medium approach over the other calculation methods in agreement with previous studies16,29,30. Another option of dose reporting mode in Acuros XB, dose-to-water, was also evaluated. Both approaches (dose-to-medium and dose-to-water) calculate the energy-dependent electron fluence based on the material properties of the interested media. Both approaches are based on the same steps of transport calculation31. The difference occurs in the post-processing step, during which the energy-dependent fluence resulting from transport calculation is multiplied by the different flux-to-dose response functions to obtain the absorbed dose value. Acuros XB uses a medium-based response function for dose-to-medium and a water-based response function for dose-to-water32. While our findings show comparable results of dose calculation around the insert for both Acuros XB approaches, the dose-to-water approach overestimates dose inside the inserts. The weak point of Acuros XB dose-to-medium approach is the rigid and non-modifiable list of high-density materials for which calculations can be made. In addition to previous studies, we performed calculations not only for titanium and stainless steel (i.e., alloy 600 in our study) but also for tungsten that is not listed in the algorithm's libraries. In order to perform calculations, we applied for the tungsten insert the closest density-similar material listed in the library, i.e., gold (19.3 g/cm3). The Monte Carlo simulations were performed for real tungsten density, i.e., 19.4 g/cm3 Therefore, the differences between the calculated and simulated doses in the tungsten insert are bigger than for the other inserts.

The worst results were observed for the AAA algorithm, which is in line with previous research17. The main limitation of this algorithm is the inability to model backscatter radiation deriving from high-density materials. This radiation generates a dose peak observed at the entrance to high-density material. Our work shows that only Monte Carlo and Acuros XB correctly model this phenomenon. However, it is worth noting that assigning an estimated one CT value for the metal (AAATD) over the CT values calculated by the CT (AAACT) scanner led to a better agreement with MC simulations.

This work also verified different strategies for metal artefact reduction. We assessed six different imaging methods: standard CT, monoenergetic CTs series reconstructed for 70 keV and 130 keV with and without the iMAR algorithm. Knowing how imaging affects the dose calculation is essential for choosing the proper metal artefact reduction method. Our study shows that the metal reduction strategies have no significant impact on the dose calculation results. Therefore, in our opinion, the selection of the most adequate CT reconstruction should be based on the preferences and experience of the person responsible for the delineation process. Dual-energy tomography and its monoenergetic reconstructions are an interesting metal artefact reduction method. One of the proposed methods is a combination obtained from dual-energy 70 keV monoenergetic scans with iMAR, which was reported12 to decrease CT number errors and increased image quality. Other work33 reported the lowest metal artefacts at 130 keV monoenergetic series without iMAR. It is important to highlight that the correct conversion from CT value to relative electron density or physical density is crucial.

A dedicated extended calibration curve should be determined and used for accurate dose calculation34. We found no significant impact of imaging mode on the dose calculation process with different strategies leading only to 2% differences and hence no disadvantages of using metal reduction strategies of choice.

This study, for the first time, compared detailed measurement around and inside the metal structure with a set of calculations by different methods using a dedicated phantom. There is a need in the future to translate and validate our phantom findings in clinical conditions.

Conclusion

The selection of the algorithm for dose calculation was shown to have a significant impact on the accuracy of dose calculation near and inside metals. The Monte Carlo class algorithm should be used for the precise dose calculation as proved by our measurements with a phantom. We found that only the Acuros XB algorithm with a dose-to-medium approach provides comparable accuracy with Monte Carlo method for dose calculation in metal regions when using Eclipse treatment planning system. The limitation of this algorithm is the need to assign material from a predefined library for the high-density objects. Based on the tungsten insert results, it was found that the inability to indicate precise atomic composition leads to calculation errors. The inability of the AAA algorithm to model backscatter dose requires caution in its clinical use for patients with metal implants. However, we found that using an estimated CT value can improve AAA dose calculation behind the metal. No significant impact on the dose calculation was found for a range of metal reduction strategies, suggesting that the choice could be made following clinical operator preference.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary materials except the selected data (i.e., phase space files) used during Monte Carlo simulations that are provided and licenced by Varian Medical Systems (Palo Alto, USA).

References

Barrett, J. F. & Keat, N. Artifacts in CT: Recognition and avoidance. Radiographics 24(6), 1679–1691. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.246045065 (2004).

Bongers, M. N. et al. Comparison and combination of dual-energy- and iterative-based metal artefact reduction on hip prosthesis and dental implants. PLoS ONE 10(11), e0143584. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143584 (2015).

Lee, M. J. et al. Overcoming artifacts from metallic orthopedic implants at high-field-strength MR imaging and multi-detector CT. Radiographics 27(3), 791–803. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.273065087 (2007).

Spadea, M. F., Verburg, J. M., Baroni, G. & Seco, J. The impact of low-Z and high-Z metal implants in IMRT: A Monte Carlo study of dose inaccuracies in commercial dose algorithms. Med. Phys. 41(1), 011702. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4829505 (2014).

Hernandez, S. et al. Development and dosimetric assessment of an automatic dental artifact classification tool to guide artifact management techniques in a fully automated treatment planning workflow. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 90, 101907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compmedimag.2021.101907 (2021).

Subhas, N. et al. Iterative metal artifact reduction: Evaluation and optimization of technique. Skeletal Radiol. 43(12), 1729–1735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-014-1987-2 (2014).

Axente, M. et al. Clinical evaluation of the iterative metal artifact reduction algorithm for CT simulation in radiotherapy. Med. Phys. 42(3), 1170–1183. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4906245 (2015).

Morsbach, F. et al. Reduction of metal artifacts from hip prostheses on CT images of the pelvis: Value of iterative reconstructions. Radiology 268(1), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13122089 (2013).

Pawałowski, B., Szweda, H., Dudkowiak, A. & Piotrowski, T. Quality evaluation of monoenergetic images generated by dual-energy computed tomography for radiotherapy: A phantom study. Phys. Med. 63, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2019.05.019 (2019).

Chapman, D., Smith, S., Barnett, R., Bauman, G. & Yartsev, S. Optimization of tomotherapy treatment planning for patients with bilateral hip prostheses. Radiat. Oncol. 9(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-9-43 (2014).

Martin, S. et al. Evaluation of tomotherapy MVCT image enhancement program for tumor volume delineation. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 12(3), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v12i3.3505 (2011).

Pawałowski, B., Panek, R., Szweda, H. & Piotrowski, T. Combination of dual-energy computed tomography and iterative metal artefact reduction to increase general quality of imaging for radiotherapy patients with high dense materials. Phantom study. Phys. Med. 77, 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2020.08.009 (2020).

Huang, J. Y. et al. Approaches to reducing photon dose calculation errors near metal implants. Med. Phys. 43(9), 5117. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4960632 (2016).

Reft C, Alecu R, Das IJ, Gerbi BJ, Keall P, Lief E, et al. AAPM Radiation Therapy Committee Task Group 63. Dosimetric considerations for patients with HIP prostheses undergoing pelvic irradiation. Report of the AAPM Radiation Therapy Committee Task Group 63. Med. Phys. 30(6):1162–82. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.1565113 (2003).

Han, T., Mikell, J. K., Salehpour, M. & Mourtada, F. Dosimetric comparison of Acuros XB deterministic radiation transport method with Monte Carlo and model-based convolution methods in heterogeneous media. Med. Phys. 38(5), 2651–64. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3582690 (2011).

Ojala, J., Kapanen, M., Sipilä, P., Hyödynmaa, S. & Pitkänen, M. The accuracy of Acuros XB algorithm for radiation beams traversing a metallic hip implant—comparison with measurements and Monte Carlo calculations. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 15(5), 4912. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v15i5.4912 (2014).

Paulu, D. & Alaei, P. Evaluation of dose calculation accuracy of treatment planning systems at hip prosthesis interfaces. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 18, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.12060 (2017).

Alhakeem, E. A., AlShaikh, S., Rosenfeld, A. B. & Zavgorodni, S. F. Comparative evaluation of modern dosimetry techniques near low- and high-density heterogeneities. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 16(5), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v16i5.5589 (2015).

Bielęda, G., Marach, A., Boehlke, M., Zwierzchowski, G. & Malicki, J. 3D-printed surface applicators for brachytherapy: A phantom study. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 13, 549–562. https://doi.org/10.5114/jcb.2021.110304 (2021).

Tino, R. et al. Additive manufacturing in radiation oncology: A review of clinical practice, emerging trends and research opportunities. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2, 22. https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-7990/ab70af (2020).

Borca, V. C. et al. Dosimetric characterization and use of GAFCHROMIC EBT3 film for IMRT dose verification. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 14, 4111. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v14i2.4111 (2013).

Sorriaux, J. et al. Evaluation of Gafchromic® EBT3 films characteristics in therapy photon, electron and proton beams. Phys. Med. 29, 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2012.10.001 (2013).

Niroomand-Rad, A. et al. Report of AAPM Task Group 235 radiochromic film dosimetry: An update to TG-55. Med. Phys. 47(12), 5986–6025. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.14497 (2020).

Constantin, M. et al. Modeling the truebeamlinac using a CAD to Geant4 geometry implementation: dose and IAEA-compliant phase space calculations. Med. Phys. 38(7), 4018–4024. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3598439 (2011).

Furuya, T. et al. Evaluation of multi-institutional end-to-end testing for post-operative spine stereotactic body radiation therapy. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 16, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phro.2020.09.005 (2020).

Cheng, Z. J., Bromley, R. M., Oborn, B., Carolan, M. & Booth, J. T. On the accuracy of dose prediction near metal fixation devices for spine SBRT. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 17(3), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v17i3.5536 (2016).

Grams, M. P. et al. Cadaveric verification of the Eclipse AAA algorithm for spine SBRT treatments with titanium hardware. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 6(2), 131–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2015.10.012 (2016).

Parenica, H. M. et al. VMAT optimization and dose calculation in the presence of metallic hip prostheses. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 18, 1533033819892255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533033819892255 (2019).

Lloyd, S. A. & Ansbacher, W. Evaluation of an analytic linear Boltzmann transport equation solver for high-density inhomogeneities. Med. Phys. 40(1), 011707. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4769419 (2013).

Kry, S. F. et al. Report dose-to-medium in clinical trials where available; A consensus from the Global Harmonisation Group to maximize consistency. Radiother. Oncol. 159, 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2021.03.006 (2021).

Failla, G. A., Wareing, T., Archambault, Y. & Thompson, S. Acuros XB advanced dose calculation for the Eclipse treatment planning system (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, 2010).

Yan, C. et al. Clinical implementation and evaluation of the Acuros dose calculation algorithm. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 18(5), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.12149 (2017).

Zhou, C. et al. Monoenergetic imaging of dual-energy CT reduces artifacts from implanted metal orthopedic devices in patients with factures. AcadRadiol. 18(10), 1252–1257 (2011).

Mullins, J. P., Grams, M. P., Herman, M. G., Brinkmann, D. H. & Antolak, J. A. Treatment planning for metals using an extended CT number scale. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 17, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v17i6.6153 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Greater Poland Cancer Center, Poznan, Poland (Grant No. 3/2021(242)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.P.—the concept of the study, literature analysis, writing the manuscript, phantom construction, EBT3 measurements and data analysis; A.R.—Monte Carlo simulations, data export and writing the manuscript; K.G.—imaging and EBT3 measurements; U.S.K.—treatment planning and data export; R.P.—the concept of the study, literature analysis, writing the manuscript; T.P.—the concept of the study, supervision of Monte Carlo simulation, data management and analysis, literature analysis, and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pawałowski, B., Ryczkowski, A., Panek, R. et al. Accuracy of the doses computed by the Eclipse treatment planning system near and inside metal elements. Sci Rep 12, 5974 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10072-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10072-8

This article is cited by

-

The accuracy of Eclipse AXB and AAA dose algorithms with dental amalgam

Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine (2024)