Abstract

We investigated the effect of specific surface area on the electrochemical properties of NiCo2O4 (NCO) for glucose detection. NCO nanomaterials with controlled specific surface areas were prepared by additive-assisted hydrothermal synthesis, and self-assembled nanostructures with urchin-, pine-needle-, tremella-, and flower-like morphologies were obtained. The novelty of this method is the systematic control of chemical reaction routes assisted by the addition of different additives during synthesis, which results in the spontaneous formation of various morphologies without any difference in the crystal structure and chemical states of the constituent elements. Such morphological control of NCO nanomaterials leads to considerable changes in the electrochemical performance for glucose detection. Combined with materials characterization, the relationship between the specific surface area and the electrochemical performance is discussed for glucose detection. This work can provide scientific insights for tailoring the surface area of nanostructures, which determines their functionality for potential applications in glucose biosensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood glucose levels provide vital information about human metabolism and physiological status1,2. For example, abnormal glucose levels in the body can be an important indicator of serious health problems, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity3,4,5. Thus, it is important to monitor blood glucose levels regularly to maintain good health. Although different types of glucose sensors using physicochemical detection have been reported, low sensitivity and slow response time are still impediments to continuous glucose monitoring systems6,7,8. In addition, the currently prevailing electrochemical glucose sensors based on enzymatic reactions have several limitations despite their advantages such as fast response, high sensitivity, and comparatively simple manufacturing procedure9,10. Accordingly, different types of non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors have been extensively studied to prevent enzyme denaturation, while maintaining the advantages of electrochemical biosensors9,11,12,13.

Transition metal-based compounds (TMCs) have sufficiently high catalytic activity toward glucose, expanding their applicability in electrochemical glucose sensors13,14,15. To date, various rational designs with facile synthetic methods for TMC have been suggested to further improve glucose detection in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, and electrochemical stability16,17,18. For example, single digit transition metal-based oxides such as copper oxide (CuO)11,19, zinc oxide (ZnO)20, nickel oxide (NiO)21,22, cobalt oxide (Co3O4)23,24, and cerium oxide (CeO2)25 present electrochemical activity towards glucose. Recent advance on the binary metal oxides such as nickel-cobaltite (NiCo2O4) for glucose detection show further synergetic effects on enhancing the electroactivity26,27,28,29,30. In particular, precise control of composition and morphology for the formation of TMCs with different nanostructures can effectively increase the detection sensitivity owing to their large surface areas, and thereby it is highly recommended to develop the TMCs with controlled morphologies for enhancing glucose detection20,25,30,31,32,33,34,35.

Herein, we report the NiCo2O4 (NCO) nanomaterials with various morphologies for glucose detection. The NCO nanomaterials were prepared by a simple hydrothermal method using various additives; chemical additives are one of the critical factors for self-assembly of nanostructures with various morphologies. We systematically investigated the effects of different morphologies of NCO on their electrochemical performance for glucose detection, including sensitivity, selectivity, low detection limits, and long-term stability.

Result and discussion

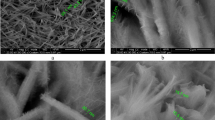

We synthesized NCO nanomaterials with urchin-, pine-needle-, tremella-, and flower-like microstructures (abbreviated as UNCO, PNCO, TNCO, and FNCO, respectively). Figure 1 shows the distinct morphologies of UNCO, PNCO, TNCO, and FNCO. The SEM image and EDS mapping indicate that Ni, Co, and O are homogeneously distributed in the NCO nanomaterials, as shown in Figs. S1 and S2, respectively. Figure 2a,b show the representative TEM images of the NCO nanomaterials with distinguishable morphologies. UNCO is a self-assembled microsphere (diameter: ~ 5 µm) consisting of nanowires with NCO nanoparticles (average particle size: 20 nm). This unique microstructure is expected to provide a large surface area, promoting electrolyte diffusion as well as electron transfer. The addition of NH4F and urea during synthesis results in a thicker pine-needle-like microstructure (PNCO) with length of 3 µm and width of 60 nm consisting of larger nanoparticles. The addition of HMT instead of NH4F results in a tremella-like morphology (TNCO) with wrinkled nanosheets. The introduction of both NH4F and HMT during synthesis leads to aggregation of neighboring wrinkled nanosheets, resulting in the formation of a flower-like morphology (FNCO). The HRTEM images (Fig. 2c) reveal clear lattice fringes with inter-planar spacings of 0.473, 0.278, 0.50, and 0.237 nm, which corresponds to the (111), (220), (311), and (222) planes of NiCo2O4, respectively27. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of the NCO nanomaterials (insets of Fig. 2b) also confirm the polycrystalline nature of NiCo2O4. The results of high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging and EDS mapping indicate that all the elements are homogeneously distributed in the NCO nanomaterials, as shown in Fig. 2d.

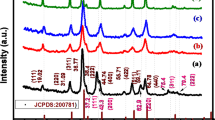

The XRD patterns of the NCO nanomaterials with various morphologies are shown in Fig. 3a. The diffraction peaks at 18.9, 31.1, 36.6, 44.6, 59.1, and 64.9° are indexed to the (111), (220), (311), (400), (511), and (440) planes, respectively of NiCo2O4 with a cubic spinel structure (JCPDS No. 20-0781)36. The FT-IR spectra of the NCO nanomaterials are shown in Fig. 3b. The two strong vibrational bands in the region between 555 and 669 cm−1 correspond to metal (Ni and Co)–oxygen stretching from tetrahedral and octahedral sites, respectively of spinel NiCo2O437. To further understand the structural properties of the NCO nanomaterials, Raman spectra were acquired, as shown in Fig. 3c. The four peaks observed at 180, 459, 503, and 642 cm−1 correspond to the Raman-active F2g, E2g, F2g, and A1g modes, respectively of spinel NiCo2O4. XPS measurements were performed to identify the surface chemical states of the elements in the NCO nanomaterials. Figure 3d shows the XPS spectra of UNCO. The Ni 2p spectra shows two major peaks located at binding energies of 854.8 and 872.3 eV corresponding to Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2 with two shakeup satellites at 860.6 and 879.1 eV, respectively. This indicates the presence of Ni2+ and Ni3+ oxidation states in NCO. The peaks at approximately 855.9 and 873.4 eV are ascribed to Ni3+, and the peaks located at around 854.2 and 871.6 eV are assigned to Ni2+. Similarly, the Co2p spectra of the two spin orbit doublets reveal the characteristic peaks of Co2+ and Co3+ at 780.4 (Co 2p3/2) and 795.7 eV (Co 2p1/2). The peaks at 796.0 and 780.3 eV are assigned to Co2+, while those at 794.4 and 779.3 eV correspond to Co3+. It is to be noted that the multi-valence states (Ni2+/Ni3+ and Co2+/Co3+) of metal ions in NiCo2O4 are beneficial for improving the electrochemical activity37,38. The Ni2p and Co2p spectra of UNCO, PNCO, TNCO, and FNCO show similar results, as shown in Fig. S3. In addition, the O1s spectra of all the NCO nanomaterials (Fig. S4) show two peaks at 592.4 and 531.2 eV, associated with typical metal–oxygen bonds and oxygen in hydroxyl groups on the surface of NCO, respectively39. Despite the structural similarities of the NCO nanomaterials, the morphological differences in the additives suggest that each additive can participate in the chemical reaction differently for the formation of NCO. This controls the energetically preferred steps for nucleation and grain growth, thus tuning the particle size and degree of agglomeration. In this manner, the control of different process parameters, including additives, reaction time, and temperature during synthesis, can be used to engineer the microstructure and improve the electrochemical performance of the NCO nanomaterials for glucose detection.

Tailoring the morphologies of NCO nanomaterials is closely related to the formation of initial phases originated from different additives depicted in Fig. S5. Furthermore, both the XRD patterns and the Raman spectra of the as-prepared samples (Figs. S6 and S7a) reveal that the participation of different chemical additives results in crystallographic differences: Ni and Co carbonate hydroxide were mainly observed in the urchin- and pine-needle-like structures, while the tremella- and flower-like structures show the presence of Ni and Co hydroxide. The FT-IR and XPS spectra of the as-prepared samples as shown in Figs. S7b to S9 also provide clear evidence for the aforementioned crystallographic differences. From the materials characterization of the as-prepared samples, it is evident that the additives participate in the hydrothermal reaction and provide different reaction pathways to prepare initial phases with various morphologies40,41,42. The self-assembly of various morphologies, consisting of one-dimensional (1D) nanowires and two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets, is attributed to the different chemical states of the initial phases (chemical states of Ni and Co ions, and functional groups) with subsequent crystal growth42,43,44,45,46,47. During the post-heat treatment, different initial phases are transformed to spinel NCO while maintaining their unique morphologies, as confirmed by Figs. 2 and 3a.

The morphological differences in the NCO nanomaterials can affect the electrochemically active surface area for glucose detection, which determines the overall electrochemical performance of the glucose sensor. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of BET was used to evaluate the pore size and specific area of the NCO nanomaterials. Figure 4 shows the BET isotherms of the different NCO nanomaterials. The BET specific area values of UNCO, PNCO, TNCO, and FNCO were evaluated to be 45.303, 43.304, 38.861, and 27.260 m2 g−1, respectively. UNCO exhibits the highest BET specific area (45.303 m2 g−1) and the largest pore volume (0.2849 cm3 g−1) coupled with narrow pore size distribution. The BET results of the NCO nanomaterials are summarized in Table 1. The N2 adsorption–desorption curves closely resemble the type-IV isotherm hysteresis loop, which implies that all the samples have a mesoporous structure48. It is expected that mesoporous UNCO with the highest surface area and largest pore volume can provide abundant active sites for redox reactions, thus promoting electrochemical performance.

The electrochemical redox reactions of the NCO nanomaterials with different morphologies for glucose detection were evaluated by CV measurements. Figure 5 shows the CV curves of the NCO nanomaterials in 0.1 M NaOH alkaline electrolyte with and without 5 mM glucose at a scan rate of 50 mVs−1. The redox peaks were observed in the absence of glucose at 0.50 and 0.35 V, corresponding to the redox reactions related to M–O (M: Ni2+, Co2+) and M*-O-OH (M*: Ni3+, Co3+) with the aid of OH− anion49. With the addition of 5 mM glucose, a significantly increased redox reaction occurs on the surface of NCO nanomaterials, which may be attributed to the oxidation of glucose to gluconolactone. Figure S10 shows the dependence of redox peak currents at scan rates of 5–100 mV s−1 in 0.1 M NaOH solution. It is evident that the redox peak currents increase with an increase in the scan rate, which suggests similar diffusion-controlled electrochemical behaviors of the NCO nanomaterials50,51. As shown in Fig. S11, electrochemical surface area (ECSA) of the UNCO, PNCO, TNCO, and FNCO were evaluated to be 2.15, 1.47, 1.2, and 1.03 cm2, respectively. This reveals that UNCO is beneficial to the electrocatalytic process to promote glucose detection.

The electrochemical performance of the NCO nanomaterials for glucose detection was investigated, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The glucose sensitivity was evaluated by the CA method, which was performed by step-wise addition of glucose at different concentrations (0.01–6 mM) in 0.1 M NaOH solution at intervals of 60 s under 0.5 V. As shown in Fig. 6a–d, the NCO nanomaterials show different sensitivities between 84.72 and 116.33 μA mM−1 cm−2 with a high correlation coefficient (R2) between 0.99 and 0.993. The calibration curve between glucose concentration and current response of the NCO nanomaterials is presented in Fig. S12. The calculated limits of detection (LOD) of the NCO nanomaterials are in the range 0.0623–0.0783 µM. Based on the results of the CA test, UNCO shows the highest sensitivity (116.33 μA mM−1 cm−2) over a wide detection range. This can be attributed to its unique urchin-like morphology consisting of a mesoporous structure with a large specific surface area, providing more abundant active sites for glucose species. The electrochemical performances of the NCO nanomaterials, as summarized in Table S1, establish the excellent electrochemical glucose detection properties of the NCO nanomaterials prepared in this study.

CA responses of (a) UNCO, (b) PNCO, (c) TNCO, and (d) FNCO electrodes with the addition of glucose to 0.1 M NaOH solution at 0.50 V. The inset shows the calibration curves for the current response of the NCO nanomaterials; CA responses of (e) UNCO, (f) PNCO, (g) TNCO, and (h) FNCO with the stepwise addition of 1 mM glucose and 0.1 mM interfering species (LA, DA, AA, and UA).

The anti-interference ability of glucose detection is another important factor for selective and sensitive detection of glucose with interfering compounds. Figure 6e–h show the anti-interference ability of the NCO nanomaterials in 0.1 M NaOH solution. General interfering molecules such as LA, DA, AA, and UA were selected and added to the electrolyte. The current response of the NCO nanomaterials to glucose is evident. However, there is no change in the current response to UA, DA, AA, and LA, which implies that NCO nanomaterials have excellent selectivity for glucose detection, regardless of their morphological differences. Figure S13 shows the stability of the NCO nanomaterials as examined by CA response in 0.1 M NaOH, where 1 mM glucose was added to the electrolyte for an extended period of time (80,000 s). The current responses of UNCO, PNCO, TNCO, and FNCO are 98.6, 97.5, 98.4, and 96.8%, respectively of the initial current upon addition of another 1 mM glucose after 80,000 s. All the NCO nanomaterials exhibited stable redox reactions for glucose species over extended durations. Especially, current signal of the UNCO retains not only 97.1% of its initial current, but also morphology and chemical bonding nature after long-term stability test for 7 days under ambient conditions (Figs. S14 and S15a). Also, the reproducibility and repeatability of the UNCO were examined as shown in Fig. S15b,c. The relative standard deviation (RSD) of the reproducibility and repeatability were calculated as 2.42 and 2.14%, respectively, which shows potential application as the glucose sensor in industrial level. It is suggested that the UNCO has excellent structural and chemical stability under oxidizing condition for glucose detection.

It is clear that the electrochemical performance of the NCO nanomaterials for glucose detection is mainly attributed to the structural merits of the initial phases prepared by the additive-assisted hydrothermal method (Fig. S16). UNCO with a large surface area possesses more abundant electroactive sites than the other nanostructures, which is helpful for improving the redox reaction between the active materials and glucose species. The mesoporous structure of UNCO can easily expose more Ni and Co sites to the electrolyte for glucose detection, leading to a rapid electrochemical response. The 1D nanowires in UNCO can further boost the diffusion rate by providing shorter transport pathways for ions and electrons. Owing to the aforementioned unique structural features, the electrochemical performance of UNCO for glucose detection is superior to that of PNCO, TNCO, and FNCO. It is suggested that the unique morphology of UNCO within the highest surface area and pore size can provide superior electrochemical performance for glucose detection.

Conclusion

The effect of specific surface area on the electrochemical performance of NCO nanomaterials was investigated. NCO nanomaterials with different specific surface areas were prepared by a facile hydrothermal method with different additives. The different additives underwent different chemical reactions during synthesis, forming different initial phases. This conduced to the self-assembly of various nanostructures with urchin-, pine-needle-, tremella-, and flower-like morphologies. Subsequent post-heating resulted in similar chemical states of crystalline NCO nanomaterials with a spinel structure, while maintaining their unique morphologies. Depending on the surface area of the different morphologies, the electrochemical performance of the NCO nanomaterials for glucose detection was considerably improved. Especially, glucose sensitivity of NCO nanomaterials with urchin-like morphology increased up to 116.33 μA mM−1 cm−2 with high correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.99 in the linear range 0.01–6 mM. This work can provide a scientific basis for morphology engineering to tune the specific surface area, which can further enhance the electrochemical performance for non-enzymatic biosensor applications.

Experimental details

Materials and reagents

Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Co(NO3)2·6H2O, urea, hexamethylene-tetramine (HMT), ammonium fluoride (NH4F), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), d-( +)-glucose, lactic acid (LA), dopamine hydrochloride (DA), l-Ascorbic acid (AA), and uric acid (UA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All of the reagents used were of analytical grade and used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of the morphology-controlled NiCo2O4

NiCo2O4 was synthesized via a simple hydrothermal method followed by post-heat treatment. Briefly, 1 mmol of nickel nitrate (Ni(NO3)2∙6H2O) and 2 mmol of cobalt nitrate (Co(NO3)2∙6H2O) were dissolved in 30 mL of distilled water. To control the morphology of NiCo2O4, additives such as urea, ammonium fluoride, and hexamethylene-tetramine (HMT) were selectively added to the above solution. Then, the whole mixture was transferred to a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave vessel and subjected to hydrothermal reaction at 120 °C for 6 h in a convection oven. After naturally cooling to room temperature, the obtained precipitate was washed with distilled water and ethanol several times by centrifugation and then dried at 60 °C overnight. Subsequently, the as-prepared sample was calcined at 400 °C for 4 h in an ambient atmosphere. The details of the experiments are presented in Table S2 of Supporting Information.

Material characterizations

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD, X’Pert-Pro MPD; PANalytical) with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm) at 40 kV and 30 mA was performed to study the structural properties of all the NCO nanomaterials. The diffraction patterns were recorded in the 2θ range 10 − 80° with a step size of 0.05°. The surface morphology and microstructure were examined by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; Nova SEM 200, FEI) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM; TALOS F200X, FEI) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The surface valence state was analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; PHI 5000 Versa Probe II, ULVAC PHI) using Al Kα radiation (hν = 1486.6 eV). The binding energies were calibrated using the C 1 s peak at 284.6 eV as the reference. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded using a Jasco-FTIR-6300 spectrometer in the wavenumber range 1500–400 cm−1 after preparing the samples on KBr pellets. Raman spectra were also obtained using a Raman spectrometer (Horiba Co., Japan) with a He–Ne laser (632.8 nm) as the excitation source. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET; BELSORP mini II, MicrotracBEL, Corp.) low-temperature N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured using a BELSORP mini II analyzer (MicrotracBEL Corp.) to evaluate the specific surface area and pore size distribution.

Electrochemical measurements

All the electrochemical measurements, such as cyclic voltammetry (CV) and chronoamperometry (CA) were performed on a PGSTAT302N potentiostat (Metrohm-Autolab) using a three-electrode system in 0.1 M aqueous NaOH solution at room temperature. A glassy carbon electrode (GC)-based working electrode, an Ag/AgCl electrode, and a platinum plate were used as the working, reference, and counter electrodes, respectively. The CVs were recorded between 0 and 0.6 V at different scanning rates of 5–100 mV s−1. To measure the ECSA, the CVs were conducted in the range of 0.1–0.2 V at different scan rates (5–100 mV s−1). The CA response of the samples to glucose was obtained at 0.5 V under stirring. For sensitivity and selectivity measurements, 0.01–6 mM glucose solutions, 0.1 mM LA, DA, AA, and UA were used in 0.1 M NaOH solution. The reproducibility of the UNCO was examined by three different electrodes with addition of 5 mM glucose at the optimal condition. The repeatability was also examined by three times of measurements by a single UNCO electrode in 6 h.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Mergenthaler, P., Lindauer, U., Dienel, G. A. & Meisel, A. Sugar for the brain: The role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. Trends Neurosci. 36, 587–597 (2013).

Gerich, J. E., Meyer, C., Woerle, H. J. & Stumvoll, M. Renal gluconeogenesis: Its importance in human glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Care 24, 382–391 (2001).

Kharroubi, A. T. & Darwish, H. M. Diabetes mellitus: The epidemic of the century. World J. Diabetes. 6, 850 (2015).

Bullard, K. M. et al. Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in adults by diabetes type—United States. Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 67, 359 (2018).

Jensen, M. H. et al. Professional continuous glucose monitoring in subjects with type 1 diabetes: retrospective hypoglycemia detection. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 7, 135–143 (2013).

Witkowska Nery, E., Kundys, M., Jeleń, P. S. & Jönsson-Niedziółka, M. Electrochemical glucose sensing: is there still room for improvement? Anal. Chem. 11271–11282 (2016).

Jernelv, I. L. et al. A review of optical methods for continuous glucose monitoring. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 54, 543–572 (2019).

Park, S., Boo, H. & Chung, T. D. Electrochemical non-enzymatic glucose sensors. Anal. Chim. Acta. 556, 46–57 (2006).

Harris, J. M., Reyes, C. & Lopez, G. P. Common causes of glucose oxidase instability in in vivo biosensing: a brief review. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 7, 1030–1038 (2013).

Diouf, A., Bouchikhi, B. & El Bari, N. A nonenzymatic electrochemical glucose sensor based on molecularly imprinted polymer and its application in measuring saliva glucose. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 98, 1196–1209 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. CuO nanowires based sensitive and selective non-enzymatic glucose detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 191, 86–93 (2014).

Mu, Y., Jia, D., He, Y., Miao, Y. & Wu, H. L. Nano nickel oxide modified non-enzymatic glucose sensors with enhanced sensitivity through an electrochemical process strategy at high potential. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 2948–2952 (2011).

Shamsipur, M., Najafi, M. & Hosseini, M. R. M. Highly improved electrooxidation of glucose at a nickel (II) oxide/multi-walled carbon nanotube modified glassy carbon electrode. Bioelectrochemistry 77, 120–124 (2010).

Veeramani, V. et al. Heteroatom-enriched porous carbon/nickel oxide nanocomposites as enzyme-free highly sensitive sensors for detection of glucose. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 221, 1384–1390 (2015).

Marco, J. F. et al. Characterization of the nickel cobaltite, NiCo2O4, prepared by several methods: An XRD, XANES, EXAFS, and XPS study. J. Solid State Chem. 153, 74–81 (2000).

Zhang, J., Sun, Y., Li, X. & Xu, J. Fabrication of NiCo2O4 nanobelt by a chemical co-precipitation method for non-enzymatic glucose electrochemical sensor application. J. Alloys Compd. 831, 154796 (2020).

Saraf, M., Natarajan, K. & Mobin, S. M. Multifunctional porous NiCo2O4 nanorods: Sensitive enzymeless glucose detection and supercapacitor properties with impedance spectroscopic investigations. New J. Chem. 41, 9299–9313 (2017).

Zhao, H., Zhang, Z., Zhou, C. & Zhang, H. Tuning the morphology and size of NiMoO4 nanosheets anchored on NiCo2O4 nanowires: the optimized core-shell hybrid for high energy density asymmetric supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. 541, 148458 (2021).

Zhuang, Z. et al. An improved sensitivity non-enzymatic glucose sensor based on a CuO nanowire modified Cu electrode. Analyst. 133, 126–132 (2008).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Tailoring the surface area of ZnO nanorods for improved performance in glucose sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 192, 216–220 (2014).

Ding, Y., Wang, Y., Su, L., Zhang, H. & Lei, Y. Preparation and characterization of NiO–Ag nanofibers, NiO nanofibers, and porous Ag: towards the development of a highly sensitive and selective non-enzymatic glucose sensor. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 9918–9926 (2010).

Cheng, X. et al. Determination of carbohydrates by capillary zone electrophoresis with amperometric detection at a nano-nickel oxide modified carbon paste electrode. Food Chem. 106, 830–835 (2008).

Casella, I. G. Electrodeposition of cobalt oxide films from carbonate solutions containing Co (II)–tartrate complexes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 520, 119–125 (2002).

Ding, Y. et al. Electrospun Co3O4 nanofibers for sensitive and selective glucose detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 542–548 (2010).

Fallatah, A., Almomtan, M. & Padalkar, S. Cerium oxide based glucose biosensors: Influence of morphology and underlying substrate on biosensor performance. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 8083–8089 (2019).

Manjakkal, L., Szwagierczak, D. & Dahiya, R. Metal oxides based electrochemical pH sensors: Current progress and future perspectives. Prog. Mater. Sci. 109, 100635 (2020).

Li, Y., Han, X., Yi, T., He, Y. & Li, X. Review and prospect of NiCo2O4-based composite materials for supercapacitor electrodes. J. Energy Chem. 31, 54–78 (2019).

Naik, K. K., Gangan, A., Chakraborty, B., Nayak, S. K. & Rout, C. S. Enhanced nonenzymatic glucose-sensing properties of electrodeposited NiCo2O4–Pd nanosheets: Experimental and DFT investigations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 23894–23903 (2017).

Naik, K. K., Gangan, A., Chakraborty, B. & Rout, C. S. Superior non-enzymatic glucose sensing properties of Ag-/Au-NiCo2O4 nanosheets with insight from electronic structure simulations. Analyst. 143, 571–579 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Ultrathin NiCo2O4 nanowalls supported on a 3D nanoporous gold coated needle for non-enzymatic amperometric sensing of glucose. Microchim. Acta 185, 1–9 (2018).

Zhu, C. et al. Identifying the conversion mechanism of NiCo2O4 during sodiation–Desodiation cycling by in situ TEM. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1606163 (2017).

Najib, S. et al. Tailoring morphology to control defect structures in ZnO electrodes for high-performance supercapacitor devices. Nanoscale 12, 16162–16172 (2020).

Xia, X., Zheng, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhao, X. & Wang, C. Synthesis of MoS2-carbon composites with different morphologies and their application in hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 39, 9638–9650 (2014).

Liu, W., Chai, G., Zhao, X., Dai, Y. & Qi, Y. Effect of different copper sources on the morphology of cuprous oxide and its application as a non-enzymatic glucose sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 321, 128485 (2020).

Liu, S., Wang, Z., Wang, F., Yu, B. & Zhang, T. High surface area mesoporous CuO: a high-performance electrocatalyst for non-enzymatic glucose biosensing. RSC Adv. 4, 33327–33331 (2014).

Bhagwan, J., Nagaraju, G., Ramulu, B., Sekhar, S. C. & Yu, J. S. Rapid synthesis of hexagonal NiCo2O4 nanostructures for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta. 299, 509–517 (2019).

Yedluri, A. K. & Kim, H. J. Enhanced electrochemical performance of nanoplate nickel cobaltite (NiCo2O4) supercapacitor applications. RSC Adv. 9, 1115–1122 (2019).

Castro, E. B. & Gervasi, C. A. Electrodeposited Ni–Co-oxide electrodes: Characterization and kinetics of the oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 25, 1163–1170 (2000).

Wang, S. et al. Time and temperature dependent multiple hierarchical NiCo2O4 for high-performance supercapacitors. Dalton Trans. 45, 7469–7475 (2016).

Wu, L., Tang, S. & Qu, R. Urchin-like NiCo2S4 infused sulfur as cathode for lithium–sulfur battery. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 30, 189–199 (2019).

Zhu, L., Wen, Z., Mei, W., Li, Y. & Ye, Z. Porous CoO nanostructure arrays converted from rhombic Co(OH)F and needle-like Co(CO3)0.5(OH)·0.11H2O and their electrochemical properties. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 20465–20473 (2013).

Bastakoti, B. P. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of binary Ni–Co hydroxides and carbonate hydroxides as pseudosupercapacitors. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 39–43 (2013).

Li, T., Li, R. & Luo, H. Facile in situ growth of Ni/Co-LDH arrays by hypothermal chemical coprecipitation for all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 18922–18930 (2016).

Wen, W., Wu, J. M., Lai, L. L., Ling, G. P. & Cao, M. H. Hydrothermal synthesis of needle-like hyperbranched Ni(SO4)0.3(OH)1.4 bundles and their morphology-retentive decompositions to NiO for lithium storage. CrystEngComm. 14, 6565–6572 (2012).

Wei, J. S. et al. Carbon dots/NiCo2O4 nanocomposites with various morphologies for high performance supercapacitors. Small 12, 5927–5934 (2016).

Xiao, J. & Yang, S. Sequential crystallization of sea urchin-like bimetallic (Ni, Co) carbonate hydroxide and its morphology conserved conversion to porous NiCo2O4 spinel for pseudocapacitors. RSC Adv. 1, 588–595 (2011).

Wang, Y., He, J., Liu, C., Chong, W. H. & Chen, H. Thermodynamics versus kinetics in nanosynthesis. Angew. Chem. 54, 2022–2051 (2015).

Sing, K. S. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 57, 603–619 (1985).

Wang, J., Qiu, T., Chen, X., Lu, Y. & Yang, W. Hierarchical hollow urchin-like NiCo2O4 nanomaterial as electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction in alkaline medium. J. Power Sources. 268, 341–348 (2014).

Hassanpoor, S. & Aghely, F. Hierarchically self-assembled NiCo2O4 nanopins as a high-performance supercapacitor cathodic material: A morphology controlled study. RSC Adv. 10, 35235–35244 (2020).

Zhan, J., Cai, M., Zhang, C. & Wang, C. Synthesis of mesoporous NiCo2O4 fibers and their electrocatalytic activity on direct oxidation of ethanol in alkaline media. Electrochim. Acta. 154, 70–76 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with the support of Korea Institute of Industrial Technology as part of "Establishment of the Rapid Manufacturing Platform for Ceramic additive Manufacturing (KITECH EH-22-0012).” This research was financially supported by the Ministery of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE, RCC20004) and Korea Industrial Complex Corp. (KICOX) through the Industrial Complex Cluster supporting program. This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (1415181036, 20018145, Implementation of Reliable FPCB Module with Peel Strength of 14 N/cm for the Integration of Battery Sensing Assembly in Electric Vehicle) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.B.J. and K.R.P. performed the electrochemical experiments, collected the results, and write the initial draft; C.B.M. and S.K. performed the investigation and resources; J.E.J. performed the formal analysis; S.C.L. and C.A. contributed the methodology and funding acquisition; H.S.H. conceived the conceptualization; D.J.K. performed the visualization of experiment data; S.H.L. supported the additional electrochemical experiments; K.M.K. supported the writing of draft; S.M. participated in the analysis of data and supervised the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jang, Kb., Park, K.R., Mo, C.B. et al. Synthetic control of the surface area in nickel cobalt oxide for glucose detection via additive-assisted wet chemical method. Sci Rep 12, 19546 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20859-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20859-4