Abstract

Hesperetin (HS), a metabolite of hesperidin, is a polyphenolic component of citrus fruits. This ingredient has a potential role in bone strength and the osteogenic differentiation. The bone loss in the orofacial region may occur due to the inflammation response of host tissues. Nanotechnology applications have been harshly entered the field of regenerative medicine to improve the efficacy of the materials and substances. In the current study, the hesperetin nanocrystals were synthesized and characterized. Then, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of these nanocrystals were evaluated on inflamed human Dental Pulp Stem Cells (hDPSCs) and monocytes (U937). Moreover, the osteoinduction capacity of these nanocrystals was assessed by gene and protein expression levels of osteogenic specific markers including RUNX2, ALP, OCN, Col1a1, and BSP in hDPSCs. The deposition of calcium nodules in the presence of hesperetin and hesperetin nanocrystals was also assessed. The results revealed the successful fabrication of hesperetin nanocrystals with an average size of 100 nm. The levels of TNF, IL6, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in inflamed hDPSCs and U937 significantly decreased in the presence of hesperetin nanocrystals. Furthermore, these nanocrystals induced osteogenic differentiation in hDPSCs. These results demonstrated the positive and effective role of fabricated nanocrystal forms of this natural ingredient for regenerative medicine purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone loss and resorption in the oral cavity are challenging due to the inflammatory nature of these phenomena. This inflammation happens because of the complex environment of the oral cavity, which contains a wide range of microorganisms. Any connections between the oral cavity and bone tissue through inflamed or exposed pulp tissue or trauma may cause local bone resorption1. Moreover, in oral infectious situations such as periodontitis bacterial by-products suppress the host tissue response and its native regenerative capacity by recruitment of inflammatory cells2,3. The inflammatory response in the oral cavity interferes with the natural healing and regeneration of bone tissue in this area4. Therefore, the suitable substance for bone regeneration in this area should provide osteogenic capacities as well as anti-inflammatory characteristics.

Natural ingredients in the human diet, such as flavonoids with polyphenolic groups, affect bone metabolism and strength5,6,7. Hesperetin (3′,5,7-trihydroxy-4-methoxyflavanone) is a metabolite of hesperidin, a flavanone subgroup of flavonoids7,8. This natural ingredient indicates a wide range of biological activities such as antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects as well as other flavonoids6,9,10,11,12,13. Moreover, hesperetin is an accessible and cost–benefit natural ingredient suggested as a bioactive substance for bone and Cartilage repair7,14.

Especially in abnormal systemic circumstances such as type I diabetes, it has been shown that hesperetin is able to suppress the high glucose inhibited osteogenesis by anti-inflammatory and antioxidative capacities8.

Nanomedicine has been introduced in regenerative medicine as a promising approach for elevating the characteristics of therapeutic substances. In most situations, the fabrication of nanoscale particles of different ingredients can improve their properties15.

Human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) are one of the available sources of mesenchymal stem cells, which are able to differentiate into various cell types. Their availability and multi-differentiation capacity make these cells a promising source of stem cells for regenerative dentistry. Although these cells indicate significant proliferation and differentiation capacities, the presence of a signaling molecule that can induce osteogenesis in these cells is essential16,17,18,19. Different studies indicated the comparable capacity of hDPSCs in bone tissue engineering with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells20,21,22.

In the current study, the authors hypothesized that by fabricating nanoscale hesperetin particles, they are able to improve this substance's characteristics for regenerative purposes. Therefore, hesperetin nanoparticles were synthesized for the first time, and their proliferative, anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and osteogenic induction capacities were evaluated.

Results and discussion

Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of hesperetin nanocrystals

Particle size

Various characteristics of nanoparticles in biomedical applications are influenced by particle size. Regarding the particle size distribution, PDI values more than 0.7 indicate the highly extensive distribution of the particle size; its analysis by the DLS method may probably be inappropriate23. Figure 1 depicts the size distribution of the formulated nanomaterials.

According to the results of DLS, an average size of 100 nm (PDI of 0.33) was demonstrated, which shows the production of mono-dispersed nanoparticles24,25.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

In the SEM image, the nanoparticles were detectable as irregular polygonal in shape. SEM evaluation demonstrated the size distribution of hesperetin powder (Fig. 2A) and hesperetin nanoparticles (Fig. 2B). The mean ± SD of the synthesized nanoparticles was 263.75 ± 214.18 nm.

Our results showed that the nanoparticle sizes differed in DLS analysis from SEM analysis. This may be due to hydrating the outer layer of the nanoparticles in the DLS method25. Sousa et al. described the same results previously26. Furthermore, aggregation of nanoparticles and non spherical shape of nanoparticles could be the reason for this difference. The synthesized nanoparticles have different dimensions, and they are flake-like (having a different aspect ratio compared to a sphere), which can cause this difference27,28,29.

Surface charge

A comparison was presented between the zeta potential (ζ) distribution of nanoparticles and the entire quantity; the corresponding measurement was − 32.9 ± 1.5 Mv (Fig. 3). The zeta potential with extreme negativity showed that the colloidal form of the nanoparticles was stable30.

Crystalline state

The associated X-ray diffraction models of free hesperetin and nanoparticles of hesperetin are presented in Fig. 4. Both of them demonstrated the distinctive crystalline peaks of 2θ, including values of 8.21°, 14.39°, 17.23°, 21.10°, 24°, 25.90°, and 29.68°25. The prepared nanoparticles showed lower X-ray diffraction than the free hesperetin, signifying the lower crystallinity and the smaller sizes28.

The molecular structure

FT-IR demonstrated free hesperetin and nanoparticles of hesperetin, and it was noted that the locations of the bands were not accompanied by any changes (Fig. 5). Two bands attributed to the operational array of the combined ether of C-O when saturated and aromatic at respective rates of 1040 cm−1 and 1260 cm−1 were demonstrated by the peaks. Moreover, aromatic diverse stretching of C=C between 1500 and 1580 cm−1, carbonyl group (C=O) band at 1635 cm−1, –OH stretching vibration at 3495 cm−1 associated with the bonding of hydrogen atom at an intermolecular level became recognized for hesperetin25. Other researchers have formerly described the identical FT-IR ranges24. It could be stated that spray drying did not alternate the chemical compositions of hesperetin.

MTT assay

Nanomedicine and the application of nanoparticles have been increased due to the significant and enhanced effects of these materials31. The fabrication and introduction of new nanoscale bioactive molecules with improved characteristics for inducing regeneration in mesenchymal stem cells provided a promising alternative15,18,31. Hesperetin is proposed as the anti-cancer agent that decreases cancer cell proliferation. The study by Yang et al. suggested that 100 μM of this substance reduced the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines32. However, as well as other flavonoids, this bioactive material represents proliferative effects on mesenchymal stem cells in low concentrations31. Xue et al. suggested that hesperetin in low concentrations promotes the proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells7. In the current study, to evaluate the proliferative concentration of nano-hesperetin on human dental pulp stem cells, various concentrations of this substance were added to each well while the control group was considered as cells alone, without any substances. The results of the MTT test after 1, 3, and 5 days were demonstrated in Fig. 6. These results indicated that not only nano-hesperetin did not have cytotoxic effects at 0.5 and 1 μM concentrations, but also it had positive proliferative effects on human dental pulp stem cells leading to significantly increasing of vital cells on day 5.

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidative tests

Hesperetin is known for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties as well as other flavonoids6,8,9,33. Pinho-Ribeiro et al. evaluated hesperidin in the rodent model to decrease inflammation-associated pain. Their results showed that this substance reduces inflammatory pain by suppressing the inflammatory cytokine cascade, NF-kß pathway, and ROS activity34. Furthermore, applying hesperidin (glycoside form of the hesperetin) for skin injuries revealed the healing properties of this component. According to the results, hesperetin inhibited oxidative stress and inflammatory signals using down-regulation of critical cytokines in the inflammatory cascade, including TNF-, IL1ß, IL-6, and IL 1035,36. These interleukins and cytokines are widely involved in different inflammatory responses in the body, such as tooth and bone inflammation6,9. In the current study, human dental pulp stem cells were treated with both hesperetin and nano-hesperetin and inflamed by bacterial LPS and. The results of this test indicate that the nanoformulation of this natural substance is much more effective than hesperetin in decreasing the inflammatory response (Fig. 7). To evaluate the effect of hesperetin and nano-hesperetin on immune cells, which are known as main components in inflammation, the test was repeated on the human monocyte cell line U937 (Fig. 8). These cells were selected since they are appropriate in vitro models for the evaluation of inflammatory responses37,38.

Alizarin Red S staining

Several pieces of evidence showed the stimulation of bone metabolism by flavonoids led to increased bone mineralization39,40. As a member of this family, hesperetin presented an increased level of mineralization in various studies41. However, due to the application of nanoparticles and improvement of biomaterials’ properties by synthesizing on the nanoscale, in the current study, the fabricated nano-hesperetin particles were added to the cell culture medium with a concentration of 1 μm. Three weeks after facing DPSCs cells to this biomaterial, the amount of mineralization was detected in each group to clarify the capacity of hesperetin particles in improving of mineralization. The results demonstrated higher mineralization induction in the nano-hesperetin group than in the hesperetin-treated and control (non-treated group) groups (Fig. 9). These results indicated a high capacity of hesperetin nanoparticles in induction of mineralization.

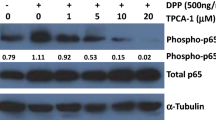

Real-time RT PCR and Western blot tests

There are several natural extracts representing bone formation by stimulating osteogenesis. Zhang et al. showed that flavonoids enhance osteogenic differentiation in hBMSCs42. Furthermore, Hokmabad et al. showed that the extract of Elaeagnus Angustifolia, a rich source of flavonoids, increased the expression of osteogenic genes43. Kim et al. evaluated the osteogenic effects of hesperetin on the differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells and proved its osteogenic capacity8.

Trzeciakiewicz evaluated this flavonoid on primary rat osteoblasts cell lines and suggested that hesperetin influences osteoblast differentiation through the BMP signaling pathway. Moreover, their results demonstrated higher expression of ALP, Runx2, and Osterix in the hesperetin-treated group41.

In the current study, the expression of five osteogenic markers, including Col1a1, BSP, Runx2, OCN, and ALP, was evaluated in gene and protein levels. The results are demonstrated in Figs. 10 and 11. The relative expression of Col1a1, BSP, Runx2, OCN, and Alp was 4.47, 4.98, 5.56, 5.13, and 5.87, respectively, in the nono-hesperetin group. These amounts were significantly higher compared to the control group. Nano- hesperetin particles elevated the expression of all evaluated genes compared to hesperetin group. This difference was significant in the expression of BSP.

Expression levels of osteogenic genes in hDPSCs treated by hesperetin and nano-hesperetin particles. The results suggested that hesperetin in both forms significantly increased osteogenesis in hDPSCs (*p ≤ 0.05). Although nanoformulation of this natural ingredient showed elevated expression levels of genes compared to the HS group, the statistical difference was only reported in BSP. Control contained cells alone without substances.

The expression of the mentioned factors in protein levels were assessed and showed a remarkable increase in the nano-hesperetin group. These data were in a line with PCR results and supported the idea of improved characteristics of bioactive molecules on the nanoscale. Hence, it could be concluded that fabricated nano-hesperetin particles could improve the biological characteristics and enhance the osteogenic induction capacity of this flavonoid.

Conclusion

The result of the current study suggested that nano-hesperetin has positive effects on osteogenic differentiation and proliferative effect on human dental pulp stem cells, nano-hesperetin can be considered an ideal option in bone and tooth tissue engineering. In addition, hesperetin nanoparticles can be applied to expand suitable scaffolds for bone, teeth, and periodontium regeneration.

Materials and methods

Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of Hesperetin nanocrystals

Hesperetin was purchased from SIGMA-ALDRICH Co. (CAS: 69097-99-0. MW: 302.28 g/mol). Two mg of hesperetin was added to 20 ml of acetone on a stirrer (450 rpm). This solution was then drop-wised into a sodium dodecyl sulfonate (SDS) solution (0.001 M) under a homogenizer (10,000 rpm). The resulting solution was then placed in a spray-drier at a 2.5 ml/min rate at 30° C to produce hesperetin nanoparticles. Then we used dynamic light scattering (DLS) technique to measure the average diameter of nanoparticles using a Nano-ZS tool (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). Nanoparticles were sonicated before size identification (Power 500 W, 20% amplitude, 30 min of response time, pulse on 2 s, and pulse off: 2 s in an ice bath) at 25 ± 1 °C. Morphology identification of nanoparticles was conducted through SEM analysis via a scanning electron microscope (SEM, TESCAN, Warrendale, PA). To fix the nanoparticles in their dry powder form, an adhesive tape was used followed by applying gold coatings. The size of nano hespertin particles was determined from SEM micrographs using Image J software (NIH, USA, version 1.52n) as described previously44.

A zeta-sizer (Malvern, UK) was used to specify the surface charge of nano-scale particles according to the evaluation of zeta potential at 25 °C using a fresh aqueous suspension of nanoparticles that perfused into the capillary cell of the zeta-sizer. The process was followed by using X-ray diffraction (XRD) method to investigate the comparison of the crystalline state of the samples in a qualitative fashion (Philips TW 1710 diffractometer with Cu-Kα incident radiation adjusted at 40 kV and 30 mA). We chose room temperature to conduct the records over the 2θ range of 20°–60° at a scanning rate of 3˚/min.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was utilized to obtain the structure of an inter/intramolecular bonding of the prepared nanomaterials (Termo Nicolet-6700, spectrophotometer) ranging from 4000 to 400 cm−1.

Determination of proliferative concentration of hesperetin nanocrystals on hDPSCs by MTT assay

For evaluation of nano-hesperetin crystals’ effects on the proliferation and viability of hDPSCs, the MTT assay was performed. For this purpose, human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) were obtained from the biobank of Shahid Beheshti University (Tehran, Iran). The cells were cultured in a culture medium containing DMEM high glucose (Gibco co.), 10% FBS (Gibco co.), and 1X pen/strep (Gibco co.) in a 75 cm2 culture flask. After obtaining 2 × 106 cells, the cells were trypsinized and cultured in three 96 well plates (5000 cells/well) to evaluate the different concentrations of nano-hesperetin after 1, 3, and 5 days. The seeded cells were exposed to nano-hesperetin at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 25 μM. After the treatment times, the medium was exchanged with 200 μl of MTT solution (0.5 mg/ml) and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, away from light. Then the medium was replaced with 200 μl DMSO. Finally, the absorbance optical density was read by a plate reader (Awareness Technologies Stat Fax 2100 Microplate Reader) at 570 nm. The percentage of living cells was evaluated by comparing the control (cells grown in the absence of nano-hesperetin). All tests were performed in three replications, and data were reported as mean ± SD.

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of hesperetin nanocrystals on inflamed U937

To evaluate the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties of hesperetin and hesperetin nanocrystals on inflamed hDPSCs, the antioxidative and anti-inflammatory tests were performed as mentioned previously45. Briefly, hDPSCs were cultured on 6 well plates (1 × 106) and inflamed with 10 ng/ml LPS of E. Coli. (Sigma-Aldrich Co. Steinem, Germany). These plates were incubated for 24 h. To investigate the concentration of TNFᾳ and IL6 in the presence of nano hesperetin (1 μM) and hesperetin nanoparticles (1 μM), the production of these cytokines was assessed using ELISA kits (DuoSet ELISA Development kit, cat No. DY210-05) according to the manufacturer protocol.

Moreover, cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels of simulated hDPSCs were evaluated by the DCFDA-ROS Detection Assay Kit (ab113851). The assay uses the cell-permeant reagent 2', 7'-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA), a fluorogenic dye that assesses hydroxyl, peroxyl, and other ROS activities within the cells. After that, DCFDA is deacetylated by cellular esterases to a non-fluorescent compound, which is later oxidized by ROS into 2', 7'-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). Intracellular ROS production was respectively detected by measuring the fluorescence intensity of cells with a microplate reader with excitation of 490 nm and emission of 530 nm wavelengths as described previously46. The measured values of fluorescence were demonstrated as fluorescence intensity/mg protein.

As the immune cell are one of the critical components in the inflammatory reactions, same tests were repeated on inflamed monocytes. These cells were purchased from Sara Research Co. as U937 cell line.

Mineralization induction of hDPSCs by hesperetin nanocrystals

To evaluate the mineralization induction capacity of hesperetin and hesperetin nanocrystals on hDPSCs, these cells were seeded with the number of 5 × 105, and the culture medium containing 1 μM hesperetin and nano-hesperetin was used for feeding these cells. The culture medium was replaced every three days. After 21 days, the Alizarin red staining was performed as mentioned previously47 to measure the induction of mineralization in hDPSCs. Briefly, the wells were washed with PBS (three times), fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min, and then washed with deionized water for 10 min. Cells were stained with 1% ARS and shook for 15 min. To quantify the results, the ARS solution was extracted by adding a 10% acetic acid solution for 30 min with constant shaking and then neutralized with a 10% ammonium hydroxide solution, which was followed by colorimetric detection at 405 nm using an ELISA reader (Bio Teck, Germany).

Expression of osteogenic genes and proteins in hDPSCs stimulated by hesperetin nanocrystals

For detecting osteogenic marker expression in the presence of hesperetin and hesperetin nanocrystals, 1 × 106 hDPSCs were cultured in each well of 6 well-plates containing osteogenic medium which included α-MEM medium supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 nM dexamethasone and 0.2 mM sodium L-ascorbyl-2-phosphate, 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate, and 10% FBS. Three wells were treated with 1 μM hesperetin, three wells were treated with 1 μM HS nanoparticles, and three wells remained untreated as the control group. After 21 days, total RNA was extracted from each sample according to our previous study48. Briefly, the wells were trypsinized, and after centrifuging a 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Cat No: 15596-026, Invitrogen, USA) was added, and then 200 μL chloroform (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added and centrifuged at 4 °C at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The upper phase containing RNA was mixed with isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 4 °C for 15 min and centrifuged at 4 °C at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. Then the supernatant was discarded, and 1 mL ethanol (75% v/v) was added to dissolve the pellet and centrifuged at 4 °C at 7500 rpm for 10 min. Then the supernatant was discarded and 20 μL water was added. The concentration of total RNA was measured with a Nanodrop system (Thermo Scientific). RNA solutions were incubated with the DNase1 kit (Cat No: en0521, Fermentaz). Then, 1 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesizing by a cDNA synthesis kit (Cat No: YT4500). The expression level of five osteogenic genes was evaluated by specific primers mentioned in Table 1. The GAPDH gene was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization. The expression was measured by an RT-PCR system, including Rotor-Gene Corbett System 6000. The experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the data were analyzed by a convenient Pfaffl method.

Western blot analysis was conducted to evaluate the expression of osteogenic proteins in hDPSCs treated with hesperetin and hesperetin nanocrystals. The samples were prepared as well as real-time PCR samples. After 21 days, the cells were collected and lysed in ice-cold cell lysis buffer solution (NaCl, NP-40, and Tris–HCl), including cocktail enzyme inhibitors. Then, the solutions were sonicated and centrifuged at 14,000g for 20 min. The total protein contents were measured in the supernatant by the Picodrop spectrophotometer system (Model No: PICOPET01, Serial No. 000212/1) and resolved by the SDS-PAGE method. The samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C in the following primary antibody solutions including Alkaline phosphatase (ALP, Cat No: ab39256, Abcam company), collagen type Ι alpha Ι (COL1α1, Cat No: sc-517593, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), osteocalcin (OCN, Cat No: sc-293414, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), Bone Sialoproteins II (BSP, Cat No: sc-73634, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), Runt-related transcription factor (RUNX2, Cat No: sc-390351, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and β-Actin (Cat No: sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). After that, the samples were incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated anti-IgG antibody (Cat No: sc-2357, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoreactive blots were detected by the ECL plus solution kit (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s instruction to visualize the reactive proteins on the blots. This experiment was performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

The data were determined as the mean ± standard deviation and comprised by using One-way ANOVA and Tukey test analysis with Prism software (version 8.0, GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (Supplementary information S1).

Ethics approval

All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), which complied with the Helsinki declaration (Approval No. IR.TBZMED.REC.1398.475).

Data availability

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Thomas, M. & Puleo, D. Infection, inflammation, and bone regeneration: A paradoxical relationship. J. Dent. Res. 90, 1052–1061 (2011).

Nair, S. P. et al. Bacterially induced bone destruction: mechanisms and misconceptions. Infect. Immun. 64, 2371–2380 (1996).

Graves, D. T. & Cochran, D. The contribution of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor to periodontal tissue destruction. J. Periodontol. 74, 391–401 (2003).

García-Henández, A. L., Serrano-Bello, J., Alvarez-Perez, M. A., Cifuentes-Mendiola, E. & González-Alva, P. The immune system and its response to polymeric materials used for craniofacial regeneration. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 1–18 (2022).

Gronthos, S., Mankani, M., Brahim, J., Robey, P. G. & Shi, S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 13625–13630 (2000).

Alipour, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of curcumin-loaded endodontic reparative material. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 35, e22854 (2021).

Xue, D. et al. The role of hesperetin on osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells and its function in bone regeneration. Oncotarget 8, 21031 (2017).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Hesperetin alleviates the inhibitory effects of high glucose on the osteoblastic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells. PLoS ONE 8, e67504 (2013).

Alipour, M. et al. The antimicrobial, antioxidative, and anti-inflammatory effects of polycaprolactone/gelatin scaffolds containing chrysin for regenerative endodontic purposes. Stem Cells Int. 2021 (2021).

Galati, E. et al. Biological effects of hesperidin, a citrus flavonoid (Note I): antiinflammatory and analgesic activity. Farmaco (Societa chimica italiana: 1989) 40, 709–712 (1994).

Ashrafizadeh, M. et al. Sensing the scent of death: Modulation of microRNAs by curcumin in gastrointestinal cancers. Pharmacol. Res. 160, 105199 (2020).

Khan, H. et al. Flavonoids targeting NRF2 in neurodegenerative disorders. Food Chem. Toxicol. 146, 111817 (2020).

Yarla, N. S. et al. in Seminars in cancer biology. 48–81 (Elsevier).

Xiao, S. et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of hesperidin enhances chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage tissue repair. J. Inflamm. 15, 1–8 (2018).

Beneficial nanomedicine against cancer. Maleki Dizaj, S. et al. Curcumin nanoformulations. Phytother. Res. 36, 1156–1181 (2022).

Alipour, M. et al. The osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells in alginate-gelatin/Nano-hydroxyapatite microcapsules. BMC Biotechnol. 21, 1–12 (2021).

Anand, P., Kunnumakkara, A. B., Newman, R. A. & Aggarwal, B. B. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 4, 807–818 (2007).

Sharifi, S. et al. Stem cell therapy: curcumin does the trick. Phytother. Res. 33, 2927–2937 (2019).

Khezri, K. et al. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via curcumin-containing nanoscaffolds. Stem Cells Int. 2021 (2021).

Nakashima, M., Iohara, K. & Murakami, M. Dental pulp stem cells and regeneration. Endod. Top. 28, 38–50 (2013).

Tsutsui, T. W. Dental pulp stem cells: Advances to applications. Stem Cells Clon. Adv. Appl. 13, 33 (2020).

Gaus, S. et al. Shared genetic and epigenetic mechanisms between the osteogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells and bone marrow stem cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2021 (2021).

Danaei, M. et al. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics 10, 57 (2018).

Fathi, M., Varshosaz, J., Mohebbi, M. & Shahidi, F. Hesperetin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructure lipid carriers for food fortification: preparation, characterization, and modeling. Food Bioprocess Technol. 6, 1464–1475 (2013).

Ersoz, M. et al. Comparative evaluation of hesperetin loaded nanoparticles for anticancer activity against C6 glioma cancer cells. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 47, 319–329 (2019).

Sousa, F. et al. A new paradigm for antiangiogenic therapy through controlled release of bevacizumab from PLGA nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–13 (2017).

Negahdari, R. et al. Curcumin nanocrystals: Production, physicochemical assessment, and in vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial effects against bacterial loading of the implant fixture. Appl. Sci. 10, 8356 (2020).

Hu, L., Kong, D., Hu, Q., Gao, N. & Pang, S. Evaluation of high-performance curcumin nanocrystals for pulmonary drug delivery both in vitro and in vivo. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 10, 381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1085-y (2015).

Fissan, H., Ristig, S., Kaminski, H., Asbach, C. & Epple, M. Comparison of different characterization methods for nanoparticle dispersions before and after aerosolization. Anal. Methods 6, 7324–7334 (2014).

Clogston, J. D. & Patri, A. K. in Characterization of nanoparticles intended for drug delivery 63–70 (Springer, 2011).

Samiei, M. et al. Influence of curcumin nanocrystals on the early osteogenic differentiation and proliferation of dental pulp stem cells. J. Nanomater. 2022, 8517543. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8517543 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Hesperetin impairs glucose uptake and inhibits proliferation of breast cancer cells. Cell Biochem. Funct. 31, 374–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbf.2905 (2013).

Pari, L. & Shagirtha, K. Hesperetin protects against oxidative stress related hepatic dysfunction by cadmium in rats. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 64, 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etp.2010.11.007 (2012).

Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A. et al. Protective effects of the flavonoid hesperidin methyl chalcone in inflammation and pain in mice: role of TRPV1, oxidative stress, cytokines and NF-κB. Chem. Biol. Interact. 228, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2015.01.011 (2015).

Takada, Y., Sethi, G., Sung, B. & Aggarwal, B. B. Flavopiridol suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced activation of activator protein-1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), p44/p42 MAPK, and Akt, inhibits expression of antiapoptotic gene products, and enhances apoptosis through cytochrome c release and caspase activation in human myeloid cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 1549–1557. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.107.041350 (2008).

Martinez, R. M. et al. Topical formulation containing hesperidin methyl chalcone inhibits skin oxidative stress and inflammation induced by ultraviolet B irradiation. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 15, 554–563. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5pp00467e (2016).

Passmore, J. S., Lukey, P. T. & Ress, S. R. The human macrophage cell line U937 as an in vitro model for selective evaluation of mycobacterial antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell function. Immunology 102, 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01164.x (2001).

Prasad, A. et al. Reactive oxygen species imaging in U937 cells. Front. Physiol. 11, 552569 (2020).

Shen, C. L. & Chyu, M. C. Tea flavonoids for bone health: From animals to humans. J. Investig. Med. 64, 1151–1157. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2016-000190 (2016).

Yamaguchi, M. Regulatory mechanism of food factors in bone metabolism and prevention of osteoporosis. Yakugaku Zasshi 126, 1117–1137. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi.126.1117 (2006).

Trzeciakiewicz, A. et al. Hesperetin stimulates differentiation of primary rat osteoblasts involving the BMP signalling pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 21, 424–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.01.017 (2010).

Zhang, J. F. et al. Flavonoids of Herba Epimedii regulate osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells through BMP and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 314, 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.012 (2010).

Hokmabad, V. R. et al. Effect of incorporating Elaeagnus angustifolia extract in PCL-PEG-PCL nanofibers for bone tissue engineering. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 13, 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11705-018-1742-7 (2019).

Hassanzadeh, A. et al. Development and biocompatibility of the injectable collagen/nano-hydroxyapatite scaffolds as in situ forming hydrogel for the hard tissue engineering application. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 49, 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2021.1877153 (2021).

Alipour, M. et al. Fabrication of a novel fibrous mat based on gliadin/ethylcellulose incorporated with triamcinolone for treatment of oral ulcers. J. Polym. Environ. 30, 2579–2588 (2022).

Mohammad Alizadeh, E. et al. Metformin protects PC12 cells against oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion injury. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 28, 622–629 (2018).

Dalirabdolahinia, E. et al. An injectable chitosan-based hydrogel reinforced by oxidized nanocrystalline cellulose and mineral trioxide aggregate designed for tooth engineering applications. Cellulose 29, 3453–3465 (2022).

Alipour, M. et al. MTA-enriched polymeric scaffolds enhanced the expression of angiogenic markers in human dental pulp stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 1 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Stem Cell Research Center personnel for their guidance and help.

Funding

This study was supported by the Dental and Periodontal Research Center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 64423).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.gh., S.M.D., M.S., S.S. contributed to designing the experiments, revising the manuscript, and supervising all experiments. M.A., S.S., S.M.D., and M.A.gh. performed all the experiments and analyzed the data. M.A., S.S., and S.M.D. wrote the manuscript and drew diagrams. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alipour, M., Sharifi, S., Samiei, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of Hesperetin nanocrystals for regenerative dentistry. Sci Rep 13, 2076 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28267-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28267-y

This article is cited by

-

Impact of two different hesperidin forms loaded on nanoscale modified borate bioglass scaffolds on rat critical-sized calvarial defects

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Antioxidant and anticancer activities of hesperetin and its novel formulations in KB cells

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2025)

-

Hesperetin for the Prevention and Treatment of Oral Cancer (A Review)

Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal (2025)

-

In-Vitro Anti-cancer Therapeutic Effects of 2D-Ti3C2-MXene-Coated Hesperetin (Ti3C2_H) against Cervical Cancer Cells

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)