Abstract

Based on the attractive properties of phosphate glass, improved molybdenum phosphate glasses of composition 40P2O5, 20MoO3, 15MgO, (25-x)Li2O, xSrO, [x = 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 mol %] were prepared via the melt-quench technique. They were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), UV–visible reflectance and Electron spin resonance (ESR). FTIR confirmed the existence of several structural phosphate groups other than MoO4 and MoO6 units. Optical analysis revealed the active species of molybdenum ions. SrO addition decreases the bandgap energy, converting the glass insulator features into semiconductor properties. The measured AC electrical conductivity (σac) increased within the temperature range of 298–473(K) and decreased in the frequency range of 0.042 kHz–1 MHz. The estimated DC electrical conductivity increased with temperature, suggesting the semiconducting behavior. The highest electrical conductivity was found in base and 5% SrO samples. Therefore, it appears that the prepared glasses are viable candidates for opto-electronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phosphate glasses excel with desirable properties such as a low melting point, high thermal expansion coefficient, and high ultraviolet transmission in contrast to common oxide glasses1,2,3. The open structure of the phosphate chain allows incorporating property modifiers such as heavy metals, transition or rare earth elements which greatly improve the glass's thermal stability and toughness as well as its chemical resistance. Phosphate glasses have achieved unique magnetic, optical, and electrical properties which meet the requirements of many modern applications1,2,3. Recently, phosphate glasses are considered promising as new solid-state electrolytes owing to their structure that permits a high mobility for protons4,5.

Many prior studies on phosphate glass have focused on the effect of both alkalis and alkaline earth oxides on its structure and properties in the context of improving its optical, physical, and electrical qualities6,7,8. Li2O-P2O5 glass was found to be an outstanding fast-conducting glass for Li+ ions. Depending on the concentration of Li2O, the addition of Li2O can improve phosphate glass's ionic conductivity6,7. Strontium oxide was also used to improve the durability of phosphate glass9,10. SrO may be useful in improving the electrical conductivity of phosphate glasses. Furthermore, Bouabdalli et al.10 Found that adding SrCO3 and Li2CO3 to the boro-phosphate matrix reduces the phonon energy via the exchange of BO4 ↔ BO3 and PO3 ↔ PO2, resulting in improved fluorescence efficiency and a longer lifetime.

MgO is utilized as a glass modifier. Its molecules break the random glass network creating bonding defects which result in free paths8,11. Because lithium ions are light and tiny, they can move freely across the glass network. The ionic conductivity of glass is affected by this phenomenon. Mg2+ ions occupy the glass system's interstitial sites and disintegrate the P-O-P bonds, generating bonding deformations. This process leads to empty cavities and easy tracking by facilitating the doped ions' movement8,11. As a result, MgO plays a crucial role in improving the samples' dielectric features.

Molybdenum oxide and P2O5 combine to generate binary glasses with a broad and continuous glass-forming range. The structure of molybdenum phosphate glass systems has received a lot of attention12,13. The presence of molybdenum ions in two different valence states Mo5+ (which occupy octahedral sites) and Mo6+ (which occupy tetrahedral and octahedral sites) was identified, and the redox [Mo5+/Mo6+] ratio increased with MoO3 concentration increase12,13. Molybdenum's six-coordinated environment was further identified in the Na2O-MoO3-P2O5 glass structure14. The electrical properties of sodium and lithium phosphate glasses were studied by impedance spectroscopy to evaluate the electronic and ionic contributions to conduction. It indicated that there is no correlation between the variation in electronic or ionic conductivity and the maximum Mo5+/Motot and Mo5+/Mo6+ ratio in these glasses14,15. An optical absorption investigation shows that increasing the MoO3 content up to 0.3 mol% results in the conversion of molybdenum ions from tetrahedral sites to octahedral sites. While the concentration of molybdenum ions that exceed 0.3 mol% assists in glass network formation16. Molybdenum phosphate glasses have received major concern for their ionic and electronic transport properties2,17,18. As known, pure ionic-conducting glasses can be used as solid electrolytes in electrochemical cells, whilst mixed ionic-electronic glass conductors have the potential to be useful as cathode materials19.

Optical and electrical properties are suitable for describing glass structure as a function of its composition and network connectivity. Previous literature indicated that reports on optical and electrical properties of glasses containing combined SrO and Li2O are limited. To the best of our knowledge, ternary P2O5, MoO3, and MgO glass systems doped with both SrO and Li2O have not been investigated.

In the current work, the structural properties of studied glasses in the system 40 P2O5, 20 MoO3, 15 MgO, (25-x) Li2O, x SrO where 0 ≤ x ≤ 20 mol% are examined based on XRD analysis, density measurements, molar volume calculations, hardness and FTIR spectroscopy. The optical properties as a function of structural changes induced by SrO addition are assessed. Moreover, the effect of SrO concentration on the electrical properties of these glasses has been reported, which may be suitable for use in opto-electronic devices.

Experimental

Glass preparation

The glass samples were obtained by melting a mixture of calculated proportions of pure materials NH4H2PO4, SrCO3, Li2CO3, MoO3, MgO in porcelain crucibles in a SiC-heated furnace (Vecstar, UK) at 1200 °C for 2 h with repeated rotation of the melts to ensure perfect blending and homogeneity. The completed molten of each sample was cast into warmed stainless-steel molds to get the desired dimensions (2 cm × 1cm). These samples were then transferred to a regulated muffle furnace at 320 °C for annealing. Keeping the samples in the furnace for 1 h, the furnace was switched off and allowed to cool at 30 °C/h to room temperature.

XRD

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was measured on fine powders of the obtained samples. Samples were ground and the fine powder was examined using a diffractometer adopting Ni-filter and Cu-target. The X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained using a Philips PW 1390 X-ray diffractometer. The diffraction patterns were identified with comparison with standard ASTM cards and published related data. The diffractometer with Cu radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å) operating at 40 kV, 30 mA, at room temperature was used. The acquired diffraction patterns are ranging from 5° to 80° for 2θ values.

Density and molar volume, microhardness

Density of glasses was measured at room temperature, using the suspended weight method based on Archimedes principle according to the following formula,

where ρ is the density of the glass sample, a and b are the weights of the glasses in the air and in xylene respectively, and 0.86 is the density of xylene at 20 °C. Molar volume of the glasses was calculated using the following formula:

where, M is the molar mass of elements in each glass sample individually, and ρ is the glass density. The specific volume of the glasses was calculated by using the inverse formula of density values.

The hardness was measured by using a Knoop diamond (KHN), under a load of 25 g, applied for 10 s (HMV microhardness tester; Shimadzu Type-M Tokyo, Japan). Three sequences of five indentations were performed.

FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was measured by (FT-IR- Brucker Vertex 8V, Germany), in the range of 1600 to 400 cm−1 wavenumbers with a resolution of 4 cm−1, to identify the structural network groupings.

Optical measurements

The diffuse reflectance spectra (DR) of the glass powders were recorded within the range of 200–1750 nm utilizing a UV–Vis near-infrared spectrometer (UV-3150, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with the ISR-3100 integrated sphere. Spectra were measured at room temperature with a 0.3-nm resolution. The Kubelka–Munk function F(R) is directly proportional to absorbance. Hence, F(R) values were altered to the linear absorption coefficient α using the next relation:

where t is the thickness of the sample.

In the limiting case of infinitely thick samples, neither thickness nor sample holder affect reflectance (R). In this case, the Kubelka–Munk equation at any wavelength becomes the following20,21:

where R = Rsample/Rstandard. As a result, the following relational expression was applied as proposed by Tauc et al.20,21.

where h is Planck's constant, ν is frequency of vibration, α is absorption coefficient, Eg is band gap n is the type of transition (1/2 in the case of direct transition or 2 in the case of indirect transition) and A1 is proportional constant.

Diffuse reflectance spectra were transformed to the Kubelka–Munk function. Thus, the vertical axis became F(R), whose value corresponded to the absorption coefficient. Then α in the Tauc equation, it is replaced with F(R). So, in the actual experiment the relational expression develops into22,23:

Consequently, getting F(R) from Eq. (4) and plotting the [F(R)hν]1/n against hν, the band gap Eg of powder samples can be obtained simply, where A2 is proportional constant.

ESR

The prepared glasses' ESR spectra were measured using an EMX spectrometer (X-band). The cavity selected was a standard Bruker ER 4102 rectangular cavity, Germany. The operating parameters were as follows: microwave power 0.796 mV, modulation amplitude 5 Gauss, time constant 81.92 ms and conversion time 20.48 ms. The powder of samples was inserted into ESR tubes and measured at the mentioned parameters. All ESR measurements were performed at 25 °C during a single scan.

Electrical measurements

The AC conductivity (σac) of the prepared samples was measured with LRC Hi-Tester (HIOKI, 3532-50), Japan, in a frequency range from 0.042 kHz to 1 MHz, and at temperatures ranging from 298 to 473 K. Temperature rising was achieved via increasing the input voltage from a variac transformer connected to a wire-wound resistance heater. In close proximity to the sample, a copper/constantan thermocouple was used to determine the temperature. The capacitance, C, and the dissipation factor, tan δ, are acquired instantly from the instrument for the samples. The AC conductivity, σac, is calculated using the relation:

where ω is the angular frequency, εο is the free‐space permittivity and ε′ is the dielectric constant which is determined from the expression

where d is the thickness of the sample and A is the cross‐sectional area24.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD)

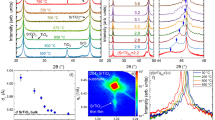

XRD is a crucial experimental method for determining structure, grain size, lattice strains, and other aspects of material characterization. The produced samples lack sharp peaks and are amorphous25 and are verified to be non-crystalline. All produced samples' XRD patterns support amorphicity as depicted in Fig. 1.

Density, molar volume and microhardness

Density measurement has been extensively studied to understand how composition affects glass structure. The network compactness, change in geometrical arrangement, cross-link density, and molar mass of the components are the primary determinants of glass density26.

The variation in measured density and calculated molar volume values of the glass samples is shown in Fig. 2, Table 1. It is observed that the successive partial substitution of Li2O with SrO results in a rearrangement and change in the geometrical configuration of the atoms in the host glass lattice. The density increased gradually up to 20 mol% SrO while the molar volume decreased as increasing SrO oxide content replacing Li2O oxide. The density increase might be explained by the fact that Li has a smaller molar mass (6.941 g/mol) than Sr (87.6200 g/mol). From another standpoint, SrO (4.7 g cm−3) has a heavier density than Li2O (2.01 g cm−3). Furthermore, the density increase (decrease in molar volume) was accompanied by the existence of varying structural units of PO2, PO3, and PO4. The conversion of some MoO6 into MoO4 and the potential increase in non-bridging oxygen support the increase in density.

Glass hardness is one of its most crucial qualities since it gauges how dense the structure is. Microhardness values show how different cation substitutions affect glass. Table 1 lists the values. The microhardness values of glass samples were raised when Li2O was replaced with SrO leading to an increase in glass network coherence. The increased glass microhardness may be attributed to the strontium-oxygen connection strength being higher than that of the lithium-oxygen link27. As known, Sr2+ has a stronger cationic field strength (0.29 A−2) than Li+ (0.26 A−2)27,28.

FTIR studies

Oxide glass FTIR investigations provide information on structure as well as the compound's oxygen coordination number, network formers, and change in oxygen bonds of the framework that is also produced by the cation modifiers. Figure 3 demonstrates the FTIR absorption spectra of the current series of molybdenum phosphate glass samples that are doped with successive increasing SrO content on expense of Li2O. It is reasonable that vibrational signals originate mostly from the phosphate matrix as it is the most predominant composition. The addition of alkali or divalent oxides induces linear chain structure of the phosphate molecule29. This structure is created by cleaving P–O–P bonds and creating non-bridged oxygens (NBOs). These divalent ions act as ionic crosslinks among NBOs of two different chains. This action is typically carried out by alkaline cations such as (Ca2+, Sr2+, Ba2+). But there are some divalent oxides such as (ZnO, MgO) form structural units (ZnO4, MgO4). As mentioned, molybdenum ions get into the glass network as a former and/or modifier when bound to four or six oxygen ions to form tetrahedral coordinated MoO4 and octahedral coordinated MoO6 units. Molybdate structural units (isolated MoO4) revealed infrared absorption at wavenumbers 920–900, 850–830, 800 and 430–410 cm−1 as established in previous published data30. Moreover, symmetric and asymmetric vibrations of Mo–O–Mo links can be noticed near 600 and 450 cm−1, respectively. Accordingly, FTIR infrared absorption spectra measurements are expected to show a clearer image of the structural lattice of the investigated phosphate glasses with varied modifier cations. The phosphate species in phosphate glasses mainly occur within the wavenumber range 1600–400 cm−1. Considering the deconvoluted FT-IR data, the current glass network has a broad spectrum of IR-active bands. Based on the literature the origin of the identified bands can be explained as follows29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

-

The absorption peaks in the wavenumber region below 600 cm−1 are related to the vibrations of modifying cations (such as Ca+, Sr2+, Na+ and Li+) at different interstitial locations. The band around 469 cm−1 corresponds to the bending oscillations of O–P–O groups, δ (PO2) modes of (PO2−)n chain units. In addition, symmetric and asymmetric Mo–O–Mo links vibration, vibrations of Mg2+ cations in their sites.

-

The presence of the absorption band at 575 cm−1 correlates with the fundamental frequency of PO4–3 or to P=O bending vibrations. The existing mode at 755 cm−1 is ascribed to υs (P–O–P) linkages in the pyrophosphate group (P2O7)4−, while those around 920 and 858 cm−1 are accredited to υas (P–O–P) linkages besides isolated MoO4.

-

The bands around 1087 and 1170 cm−1 are determined from asymmetric stretching vibration of the (PO3)2− terminal group, υas (PO3)2−.

It was observed that the location, widening and intensity of absorption bands are affected by Sr ions’ entrance. The band at 441 cm−1 disappeared with Li2O decrease. The peaks in the wavenumber range 400–580 cm−1 became one medium broad peak at wavenumber around 511 cm−1 by SrO addition. Moreover, vibrations spanning between 1000 and 1300 cm−1 and the disappearance of the band at 850–860 cm−1 illustrate the modification behavior of SrO in the phosphate lattice. This is done through the formation of different anionic groups or NBOs. These groups are categorized as PO2−, PO32−, and PO43−, found in Q2, Q1, and Q0, respectively35,36. The observed peaks at 1240-1290 and 1013 cm−1 with different SrO contents are ascribed to asymmetric stretching oscillations of O-P-O links of (PO2−)as and (PO32−)as located in Q2 and Q1 units, respectively35,36. Thus, all the vibration bands detected in the infrared spectrum are within the framework of the modification of the molybdenum phosphate glass network. This modification is associated with the strontium oxide content.

Optical properties

The normalized absorption spectra of 40% P2O5, 20% MoO3, 15% MgO, (25-x) Li2O, and x % SrO are shown in Fig. 4. Based on the Kubelka–Munk function, these spectra were transformed from diffuse reflectance spectra as clarified elsewhere23. Optical absorption data indicate interesting variations upon continuous substitution of specific ratios of Li2O with SrO. This is correlated to the strong effect of the existing alkaline oxides, magnesium, and strontium oxide on the optical characteristics of the studied glass lattice. Whereas the incorporation of alkaline earth elements into the glass matrix depolymerizes the glass network then stimulates the formation of non-bridging oxygen species (NBO). Furthermore, the presence of MgO and successive addition of SrO at expense of Li2O, is expected to cause variations in the ligand field around the Molybdenum probe ion owing to alterations in the oxygen ion polarizability that surrounding molybdenum ion as well as its reliance on the field strength of the glass matrix37,38. Otherwise, some previous studies39,40,41 focused on UV–visible investigations of molybdenum ions in glass. They realized that it is acceptable for molybdenum ions to exist in the glass matrix as either trivalent, tetravalent, pentavalent, hexavalent, or a mixture of some of them. Weyl42 attributed the green color of phosphate glass to pentavalent molybdenum ions under severely reducing conditions and suggest that the Mo-doped glasses display blue-green, green, brown, violet, and faint yellow resulting from Mo6+, Mo5+, Mo4+, and Mo3+ ions. ElBatal et al.42,43 and others34,44 investigated the structure and optical features of some phosphate glasses doped with MoO3. They reached to that the presence of Mo6+, Mo5+, Mo4+ and Mo3+ ions together within the studied glasses. In addition, each valence state of molybdenum ions is characterized by a specific visible absorption band. Mo3+ and Mo5+ions display absorption bands at 350–370 nm and 420–450 nm, Mo4+ ions are assigned at 550–580 nm beside the visible absorption in the wavelength range 700–960 nm is correlated to Mo5+ ions.

As depicted in Fig. 4 the present glasses reveal an appearance of UV–visible absorption bands with some changes associated with the consecutive substitution of Li2O with SrO. The first sample with 0 SrO content shows UV-near visible absorption peaks at about 216, 260, and 322 nm accompanied by a visible absorption peak at 480 nm plus weak broad absorption in the 800–1000 nm wavelength range. The UV-near visible spectrum range in the glass samples with 10–20 mol% SrO extended and show extra absorption peaks at 346 and 390 nm. With SrO content increases the absorption intensity of the band at 480 nm increases and shifts to higher wavelength at 557 and 510 nm in 10% and 15% SrO. The broad visible absorption at 800–1000 nm reached the highest intensity and shifted to lower wavelength centered at 765 nm in the highest SrO content glass sample. The identified absorption in UV region could be clarified as it was studied by many researchers, and they attribute it to trace iron impurities (Fe3+) that are indeed contaminate the raw materials45,46. Urbach47 attributes this UV absorption edge to electron transitions between oxygen 2p and transition metal ion 3d states. It is noteworthy, the highest intensity of the broad band observed in the spectrum of glass sample that contains 20% SrO suggests that this glass includes the highest concentration of Mo5+ ions. It is expected that such Mo5+ ions will form Mo5+O3− molecular orbital states and take part in the depolymerization of the glass matrix44,48, leading to more bonding defects and non-bridged oxygens (NBO’s). It is obvious that glass samples' absorption spectra comprise expanded UV-near visible peaks alongside the observed wide peak centered at about 760 nm. It is clear from this that the investigated molybdenum phosphate glasses reveal absorption bands which elucidate that the valences of molybdenum ions (Mo3+, Mo4+, Mo5+ and Mo6+) substantially exist with varied ratios. While the hexavalent state of Mo ions (d0) exhibit UV band that may interfere with strong charge transfer peaks due to trace iron contaminants, it cannot be excluded39.

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, especially the bandgap energy, is valuable for probing optically induced transitions. Furthermore, it provides information on the structural characteristics of glass. Figure 5 illustrates the diffuse reflectance (DR) spectra of the prepared glasses within wavelength range of 200–1800 nm. DR spectra demonstrate that the samples behave in the same manner as reflectivity increases at wavelengths higher than 800 nm. Additionally, different DR peaks of the samples can be seen in the UV–visible range at λ ≈ 300 to 800 nm reflects the electronic transformations of Molybdenum ions in glass matrices.

The determination of the optical transition (optical band gap) relates to the optical absorption coefficient (α) which was derived as aforementioned from Kubelka–Munk relation20,21,22,23.

where n determines the nature of electronic transition. It is well known that optical transitions take place directly (n = 1/2) or indirectly (n = 2) across the region between conduction and valence bands (optical band gap). These transitions in vitreous materials like glass, are almost indirect transitions, i.e., the effects of glass forming anions on the conduction band and cations, play a significant role in indirect transition which is always associated with absorbing or releasing phonons49. Figure 6 depicts (αhν)1/2 versus photon energy (hν) for studied samples. The linear extrapolation of the curves to the hν axis at (αhν)1/2 = 0 gives the value of the optical energy band gap for indirect Eopt transitions.

SrO and the base glass lattice affect the optical band gap energy in the present glass system. By increasing the SrO concentration, the indirect transition values decreased from 3.22 to 2.17 eV. It has been acknowledged that the oxygen bond strength forming the glass network directly influences the absorption edge location. These links are broken with network modifiers resulting in non-bridged oxygen. One end of the glass network structural unit is partially associated with these oxygen ions, which are partially negative in charge. Thus, the change in Eopt can be correlated with the change in the glass lattice, which influences cross-linking density50. The Fig. 7 shows how the bandgap energy Eg declines as the SrO content increases. This reduction may be attributed to the increase in non-bridged oxygen within the glass matrix, caused by replacing Li2O with SrO. These oxygens significantly contribute to the valence band due to their energy. Since non-bridging oxygens are more energetic and active than bridging oxygens, valence band energy rises and Eg decreases. Additionally, with a higher atomic number, coordination number, and ionic radius, the conduction band moves down more frequently. By creating non-bridging oxygen and decreasing glass structural tightness, Eg is lowered38,50.

ESR results

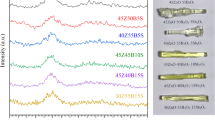

ESR spectroscopy was used to confirm the status of molybdenum ions in glass samples and approve the UV–visible findings. Figure 8 displays ESR spectra at room temperature of the studied molybdenum phosphate glasses where successive portions of Li2O were replaced by SrO. The spectra exhibit a hyperfine structure with resonance lines have g-values, parallel at g||= 1.91716 and perpendicular at g⊥ = 1.93602 which are corresponding to octahedrally coordinated Mo5+ ions paramagnetic active species, the octahedron being trigonally distorted51. It is observed that with an increase in SrO content in glass composition from 0 to 20 mol%, there is no change in g-values. However, there is a noticeable increase in signal intensity. The increase may be due to the charge transition transfer between Mo6+ and Mo5+41,51.

Electrical conductivity

Figure 9 illustrates the logarithmic variation of AC conductivity (log σac) as a function of frequency for all samples at room temperature (298 K) covering a frequency range from 0.042 kHz to 1 MHz. At lower frequencies, a plateau region of independent frequency appears which corresponds to DC conductivity52. However, in higher frequency regions, AC conductivity is more frequency-dependent. According to Fig. 9, the AC conductivity of the samples increases with frequency, implying that they are of a semiconducting character53. The increase in AC conductivity of the material with increasing frequency can be attributed to the release of space charges caused by a decrease in the material's barrier properties54. As an example, sample Sr5 exhibits an AC conductivity value of approximately 1.43 × 10–5 S cm−1 at lower frequencies, up to about 50 kHz, which then increases to 1.84 × 10–4 S cm−1 at 1 MHz, as detailed in Table 2.

The frequency dependence of conductivity (σac) for samples Sr5 and Sr15 (chosen as representative samples) is illustrated in Fig. 10a,b at different temperatures. It is evident from the figure that the σac increases with increasing frequency. Furthermore, as the temperature increases the values of conductivity rise. This observation strongly suggests that the electrical conductivity of the material is a thermally activated process55.

Figure 11 displays the temperature-dependent DC electrical conductivity of glass samples with the composition 40 P2O5 − 20 MoO3 − 15 MgO-(25-x) Li2O-x SrO, featuring varying SrO content. The electrical conductivity σdc is thermally activated process and follows the Arrhenius relation

where σo is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy for conduction, T is the absolute temperature and k is the Boltzmann constant. The figure reveals that the electrical conductivity (σdc) of these glasses increases with temperature across the entire temperature range, indicating their semiconducting nature56. At the high temperature region ranging from 413 to 473 (K), the DC activation energies (Ea(dc)) are determined from the slopes of the straight lines of the log σdc plots versus 1000/T plots and the values are listed in Table 2. The range of activation energy values falls between 0.13 and 2.15 (eV).

In addition, in Fig. 11, it can be noticed that the σdc of the samples Sr0 and Sr5 exhibits a non-linear increase with rising the measuring temperature, featuring two distinct regions. These two regions are formed by two different mechanisms. The first region, at lower temperatures ranging from room temperature up to approximately 373 K, is characterized by low activation energy. This behavior is attributed to electronic transition mechanisms, likely facilitated by the presence of molybdenum ions in multivalent states (Mo3+, Mo4+, Mo5+, and Mo6+)57 as confirmed by UV–visible spectra. While the second mechanism observed at higher temperatures (413–473 K) exhibits higher activation energy. This is primarily due to ionic movement mechanisms driven by the mobility of charge carriers, specifically Li+ ions.

Furthermore, for samples Sr10, Sr15, and Sr20, it is evident that the electrical conductivity (σdc) increases linearly with rising temperature, accompanied by relatively low activation energies ranging from 0.13 to 0.37 eV. The substantial decrease in Li+ concentration due to the substitution of lithium ions with alkaline-earth metal ions is expected to lead to a reduction in the number of ionic carriers, consequently resulting in decreased ionic conductivity. Moreover, the replacement of Li2O by SrO is found to increase the presence of non-bridging oxygen (NBO) ions, a finding confirmed by UV–visible spectra. This increase in NBO ions, in turn, enhances the mobility of charge carriers, primarily electrons. This explains the decrease of the Ea(dc) with the addition of SrO and suggests that the conduction in glass samples Sr10, Sr15 and Sr20 is mainly electronic.

Figure 12 illustrates the variations in both room temperature DC electrical conductivity (σdc) and activation energies (Ea(dc)) as a function of SrO concentration (in mol%). It is evident from this figure that σdc decreases from 1.10 × 10–6 to 8.31 × 10–8 (S/cm) as the SrO concentration increases from 0 to 20 mol%. Notably, the plot exhibits a maximum value when x = 5 mol% of SrO. To elucidate this behavior, it is worth noting that various studies suggest that alkali ions contribute more significantly to the conductivity of oxide glasses doped with alkali and alkaline earth ions, whereas alkaline earth ions have a less pronounced effect58,59. As a result, Li2O ion species exhibit greater mobility and ease of diffusion compared to SrO ion species within the glass matrix. Consequently, in the present study, the initial replacement of SrO concentration (at 5 mol%) leads to an increase in σdc, reaching 1.64 × 10–5 S/cm, accompanied by a decrease in activation energy.

Additionally, the increase in conductivity can be attributed to structural modifications within the phosphate network. The presence of SrO is known to induce a loosening effect on the glass matrix10,60. Consequently, this structural change facilitates the migration of conducting ions (Li+ ions), which are smaller (90 pm) compared to Sr2+ ions (132 pm). This size disparity enhances ion mobility, resulting in increased conductivity. In this context, both Li+ ion concentration and the introduction of non-bridging oxygen species, a result of adding the modifier oxide SrO9, can influence glass conductivity. This effect is especially notable during the initial replacement with 5 mol% SrO in sample Sr5, leading to an increase in conductivity.

With further replacement of SrO, both the conductivity and activation energy decrease. This drop in conductivity is attributed to the increased presence of less mobile SrO ions at the expense of more mobile Li2O ions, resulting in reduced conductivity for the glass samples Sr10, Sr15, and Sr20. However, the increased number of non-bridging oxygens (NBO) with a higher concentration of SrO suggests the dominance of electronic conduction with lower activation energy. The nonlinear variation of activation energy and DC conductivity within the studied glass compositions is attributed to the occurrence of a mixed cation effect58.

Conclusions

Improved molybdenum phosphate glasses with the composition 40 P2O5, 20 MoO3, 15 MgO, (25-x) Li2O, x SrO where 0 ≤ x ≤ 20 mol % were prepared via the melt-quenching technique. Increasing the strontium oxide content leads to enhanced packing of coordination polyhedra in the glass network, resulting in increased glass density and hardness. This compactness arises from Sr2+ ions occupying interstitial spaces within the network structure. FTIR of the base glass Sr0 displayed the characteristic absorption bands of oscillation modes of the basic building blocks of the glass lattice PO2, PO3, PO4−, MoO4−. The introduction of SrO into the glass network led to modifications as phosphate chains depolymerized, driven by the modifying behavior of Sr2+ ions. FTIR deconvoluted spectra confirmed structural network modifications associated with increasing SrO content, up to 20 mol%. The optical measurements revealed the presence of diverse active molybdenum ion species incorporated into the glass network. They explained the role of modifier ions in the structural network leading to an increase in non-bridging oxygen. Consequently, the bandgap energy decreased, transforming the glass from an insulator with its characteristic features into a material exhibiting semiconductor properties. Temperature dependent DC electrical conductivity was investigated. The samples' electrical conductivities increase with temperature, revealing semiconducting behavior. It was observed that the conductivity of Sr0 and Sr5 samples was the highest. This may be due to the dominance of lithium ions over their conductivity. As the concentration of strontium oxide increases beyond 5 mol%, the observed conductivity may be mainly electronic, which can be attributed to the hopping of electrons between multivalent states of molybdenum in addition to the enhanced electrons created by the increasing number of NBO ions. For samples with SrO ˃ 5 mol%, the dominance of electronic mechanism over the ionic transfer ones may present good candidates for semiconductor materials in electronic devices. In addition, the investigated glass compositions exhibited favorable optical and electrical properties, enhancing their suitability for applications in opto-electronic devices.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Brow, R. K. Review: the structure of simple phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 263&264, 1–28 (2000).

Černošek, Z., Holubová, J. & Hejda, P. The influence of phosphorus substitution by molybdenum on the chemical composition and certain properties of the zinc metaphosphate glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 522, 119556 (2019).

Vedeanu, N. S. & Magdas, D. A. The influence of some transition metal ions in lead- and calcium-phosphate glasses. J. Alloys Compds 534, 93–96 (2012).

Melo, B. M. G. et al. Structural and thermal characterization of phosphate based glasses promising for hydrogen absorption. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 434, 28–35 (2016).

Abe, Y., Hosono, H., Ohta, Y. & Hench, L. L. Protonic conduction in oxide glasses: Simple relations between electrical conductivity, activation energy, and the O–H bonding state. Phys. Rev. B 38(14), 10166–10169 (1988).

Pershina, S. V., Antonov, B. D. & Leonidov, I. I. Effect of MoO3 on structural, thermal and transport properties of lithium phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 569, 120944 (2021).

Ouachouo, L., Es-soufi, H., Sayyed, M. I., Ghyati, S. & Bih, L. Investigation of structural, thermal, and electrical characteristics of zirconium-doped lithium-phosphate glasses. Heliyon 9, e19364 (2023).

Jlassi, I., Sdiri, N. & Elhouichet, H. Electrical conductivity and dielectric properties of MgO doped lithium phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 466–467, 45–51 (2017).

Bouabdalli, E. M. et al. Structural, physical, thermal and optical spectroscopy studies of the europium doped strontium phosphate glasses. Inorganic Chem. Commun. 151, 110563 (2023).

Bouabdalli, E. M., El Jouad, M., Touhtouh, S. & Hajjaji, A. First investigation of the effect of strontium oxide on the structure of phosphate glasses using molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 220, 112068 (2023).

Sreeram, N. et al. Ascendancy of Cr2O3 on morphology, spectroscopic and dielectric properties of GeO2–Li2O–P2O5–MgO glasses. Mater. Chem. Phys. 304, 127889 (2023).

Bih, L., Nadiri, A. & El Amraoui, Y. Investigation of the physico-chemical properties of NaPO3-MoO3 glasses. J. Phys. IV France 123, 165–169 (2005).

Santagneli, SH. et al. Structural studies of NaPO3−MoO3 glasses by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance and Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 10109–10117 (2007).

Bih, L. et al. Electrical properties of glasses in the Na2O–MoO3–P2O5 system. Mater. Lett. 50,308–317 (2001).

Chowdari, B. V. R., Tan, K. L., Chia, W. T. & Gopalakrishnan, R. Thermal, physical, electrical and XPS studies of the Li2O:P2O5: MoO3 glass system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 128, 18–29 (1991).

Lakshmana Rao, B., Jyothi Raju, K. & Prasad, S. V. G. V. A. Optical absorption spectra of PbO-Sc2O3-P2O5 glasses doped with molybdenum ions. Mater. Today Proc. 5, 26298–26303 (2018).

Bih, L. et al. Electronic and ionic conductivity of glasses inside the Li2O–MoO3–P2O5 system. Solid State Ion. 132, 71–85 (2000).

Mogus-Milankovic, A., Santic, A., Karabulut, M. & Day, D. E. Study of electrical properties of MoO3–Fe2O3–P2O5 and SrO–Fe2O3–P2O5 glasses by impedance spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 330, 128–141 (2003).

Mugoni, C., Montorsi, M., Siligardi, C. & Jain, H. Electrical conductivity of copper lithium phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 383, 137–140 (2014).

Kubelka, P. New contribution of optics of intensely light materials. JOSA. 38, 448–457 (1948).

Brow, R. K. Review: The structure of simple phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 263, 1–28 (2000).

Tauc, J. & Menth, A. Localized states in the gap. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 8–10, 569–585 (1972).

Lia, H. et al. Structures, thermal expansion, chemical stability and crystallization behavior of phosphate-based glasses by influence of rare earth. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 522, 1196021 (2019).

Shukla, N., Pathak, H. P., Rao, V. & Dwivedi, D. K. A. C. conductivity and dielectric properties of Se90Cd6Sb4 glassy alloy. Chalcogenide Lett. 13, 177–185 (2016).

Cullity, B. D. Elements of Diffraction Quasi-Optics (Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Inc., 1978).

Jha, P. K., Pandey, O. P. & Singh, K. Structure and crystallization kinetics of Li2O modified sodium-phosphate glasses. J. Mol. Struct. 1094, 174–182 (2015).

Du, J. & Xiang, Y. Effect of strontium substitution on the structure. Ionic diffusion and dynamic properties of 45S5 bioactive glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 358, 1059–1071 (2012).

Hill, R. G. et al. The influence of strontium substitution in flouroapatite glasses and glass-ceramics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 336, 223–229 (2004).

Marzouk, M. A., Hamdy, Y. M. & ElBatal, H. A. Photoluminescence and spectral performance of manganese ions in zinc phosphate and barium phosphate host glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 458, 1–14 (2017).

Marzouk, S., Abo-Naf, S. M., Hammam, M., El-Gendy, Y. A. & Hassan, N. S. FTIR spectra and optical properties of molybdenum phosphate glasses. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 7(6), 935–946 (2011).

Ouis, M. A. & Gamal, A. A. Role of silver ions in Na2O-CaF2-P2O5 host glass and its corresponding glass-ceramic: Searching for antibacterial behaviour-supplemented by spectral, optical, FTIR and SEM investigations. Egypt. J. Chem. 64(9), 5353–5363 (2021).

Misbah, M. H., El-Kemary, M. & Ramadan, R. Effect of Mg2+ coordination on the structural and optical properties of iron magnesium phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 569, 120987 (2021).

Ouis, M. A., Azooz, M. A. & ElBatal, H. A. Optical and infrared spectral investigations of cadmium zinc phosphate glasses doped with WO3 or MoO3 before and after subjecting to gamma irradiation. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 494, 31–39 (2018).

El-Batal, A. M., Saeed, A., Hendawy, N., El-Okr, M. M. & El-Mansy, M. K. Influence of Mo or/and Co ions on the structural and optical properties of phosphate zinc lithium glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 559, 120678 (2021).

Sułowska, J., Wacławska, I. & Olejniczak, Z. Structural studies of copper-containing multicomponent glasses from the SiO2–P2O5–K2O–CaO–MgO system. Vib. Spectrosc. 65, 44–49 (2013).

Omrani, R. O. et al. Structural and thermochemical properties of sodium magnesium phosphate glasses. J. Alloys Compds. 632, 766–771 (2015).

Farouk, M., Samir, A. & El Okr, M. Effect of alkaline earth modifier on the optical and structural properties of Cu2+ doped phosphate glasses as a bandpass filter. Phys. B Phys. Condens. Matter 530, 43–48 (2018).

Sastry, S. S. & Rao, B. R. V. spectroscopic studies of copper doped alkaline earth lead zinc phosphate glasses. Phys. B 434, 159–164 (2014).

ElBatal, F. H., Abdelghany, A. M. & Elwan, R. L. Structural characterization of gamma irradiated lithium phosphate glasses containing variable amounts of molybdenum. J. Mol. Struct. 1000, 103–108 (2011).

Ivascu, C., Timar Gabor, A., Cozar, O., Daraban, L. & Ardelean, I. FT-IR, Raman and thermoluminescence investigation of P2O5–BaO–Li2O glass system. J. Mol. Struct. 993, 249–253 (2010).

Turky, G. M., Fayad, A. M., El-Bassyouni, G. T. & Abdel-Baki, M. Dielectric and electrical properties of MoO3-doped borophosphate glass: Dielectric spectroscopy investigations. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32, 22417–22428 (2021).

Weyl, W. A. Coloured Glasses, Monograph Reprinted by Dawson’s of Pall Mall, London (1959).

ElBatal, F. H., Abo Naf, S. M. & Marzouk, S. Y. Gamma ray interactions with MoO3-doped lead phosphate glasses. Philos. Mag. 91(3), 341–356 (2011).

Rao, B. L., Raju, K. J. & Prasad, S. V. G. V. A. Optical absorption spectra of PbO-Sc2O3-P2O5 glasses doped with molybdenum ions. Mater. Today Proc. 5, 26298–26303 (2018).

Es-soufi, H. & Bih, L. Effect of TiO2 on the chemical durability and optical properties of Mo-based phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 558, 120655 (2021).

Ehrt, D., Ebeling, P. & Natura, U. UV Transmission and radiation-induced defects in phosphate and fluoride–phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 263–264, 240–250 (2000).

Urbach, F. The long-wavelength edge of photographic sensitivity and of the electronic absorption of solids. Phys. Rev. 92(5), 1324 (1953).

Toloman, D. et al. The modifier / former role of MoO3 in some calcium-phosphate glasses. J. Alloys Compds. 556, 67–70 (2013).

Fayad, A. M., Shaaban, Kh. S., Abd-Allah, W. M. & Ouis, M. Structural and optical study of CoO doping in borophosphate host glass and effect of gamma irradiation. J. Inorganic Organomet. Polym. Mater. 30, 5042–5052 (2020).

Abdel-Baki, M., Mostaf, A. M., Fayad, A. M., El-Bassyouni, G. T. & Turky, G. M. Improving the optical, electrical, and dielectric characteristics of MgO doped borate glass for optoelectronic applications. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 065102 (2023).

Abo-Naf, S. M., Elwan, R. L. & ElBatal, H. A. Photoluminescence, optical properties, thermal behavior and nanocrystallization of molybdenum-doped borobismuthate glasses. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 29, 4915–4925 (2018).

Zangina, T. et al. Sintering behavior, ac conductivity and dielectric relaxation of Li1.3Ti1.7Al0.3(PO4)3 NASICON compound. Results Phys. 6, 719–725 (2016).

Morsi, R. M. M., Basha, M. A. F. & Morsi, M. M. Synthesis and physical characterization of amorphous silicates in the system SiO2-Na2O–RO (R = Zn, Pb or Cd). J. Non-Cryst. Solids 439, 57–66 (2016).

Gomaa, M. M., Abo-Mosallam, H. A. & Darwish, H. Electrical and mechanical properties of alkali barium titanium alumino borosilicate glass-ceramics containing strontium or magnesium. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 20, 507–516 (2009).

Song, C. H., Choi, H. W., Kim, M., Jin, G. Y. & Yang, Y. S. Electrical relaxations of amorphous xKNbO3 − (1–x)SiO2 (x = 0.33, 0.5, 0.67, 0.8). J. Korean Phys. Soc. 51(2), 674–677 (2007).

Banagar, A. V., Kumar, M. B., Nagaraja, N., Tipperudra, A. & Jakati, S. DC electrical conduction in strontium vanadium borate glasses. Mater. Sci. 38(2), 359–366 (2020).

Elalaily, N. A., Zahran, A. H., Sallam, O. I. & EzzEldin, F. M. Structure and electrical conductivity of ɤ-irradiated lead–phosphate glass containing MoO3. Appl. Phys. A https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-019-2414-2 (2019).

Thipperudra, A., Nagaraja, N., Prashanth Kumar, M. & Arun Kumar, B. AC conductivity and dielectrics studies in potassium, strontium doped borophosphate glasses. Int. J. Innov. Res. Multidiscip. Field 6, 93–98 (2020).

Bahgat, A. A. & Abou-Zeid, Y. M. Mixed alkali effect in the K2O–Na2O–TeO2 glass system. Phys. Chem. Glasses 42, 361–370 (2001) ([Mkami, H. E., Deroide, B., Backov, R. & Zanchetta, J. V. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 61, 819–826 (2000)]).

Mroczkowska, M. et al. Micro Raman, FT-IR / PAS, XRD and SEM studies on glassy and partly crystalline silver phosphate ionic conductors. J. Power Source 173, 729–733 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.F., M.A.O., R.M.M.M., R.L.E. Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fayad, A.M., Ouis, M.A., Morsi, R.M.M. et al. Enhancement of electrical conductivity associated with non-bridged oxygen defects in molybdenum phosphate oxide glass via doping of SrO. Sci Rep 13, 18321 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45333-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45333-7

This article is cited by

-

Bi2O3-Induced Modulation of Structure and Multifunctional Properties in Li2O–TeO2–P2O5 Glasses: From Optical Bandgap to Mechanical Strength

Journal of Electronic Materials (2026)

-

NaMoO2PO4 glass ceramic nanocomposite as a novel cathode material for magnesium-ion batteries

Ionics (2025)

-

Comprehensive Characterization of xV2O5-(0.3−x)Li2O-0.35TeO2-0.35P2O5 Glasses: Influence of V2O5 Concentration on Electrical, Optical and Mechanical Properties

Journal of Electronic Materials (2025)

-

Dielectric properties, relaxation time and conduction behavior of MoO3 doped V2O5–ZnO–CuO glassy semiconducting system

Applied Physics A (2024)

-

Investigation of structural, morphological and dielectric properties of yttrium magnesium silicate oxyapatite doped with Gd3+ ions

Emergent Materials (2024)