Abstract

This study aims to optimize the power generation of a conventional Manzanares solar chimney (SC) plant through strategic modifications to the collector inlet height, chimney diameter, and chimney divergence. Employing a finite volume-based solver for numerical analysis, we systematically scrutinize influential geometric parameters, including collector height (hi = 1.85 to 0.1 m), chimney inlet diameter (dch = 10.16 to 55.88 m), and chimney outlet diameter (do = 10.16 to 30.48 m). Our findings demonstrate that reducing the collector inlet height consistently leads to increased power output. The optimal collector inlet height of hi = 0.2 m results in a significant power increase from 51 to 117.42 kW (~ 2.3 times) without additional installation costs, accompanied by an efficiency of 0.25%. Conversely, enlarging the chimney diameter decreases the chimney base velocity and suction pressure. However, as turbine-driven power generation rises, the flow becomes stagnant beyond a chimney diameter of 45.72 m. At this point, power generation reaches 209 kW, nearly four times greater than the Manzanares plant, with an efficiency of 0.44%. Nevertheless, the cost of expanding the chimney diameter is substantial. Furthermore, the impact of chimney divergence is evident, with power generation, collector efficiency, overall efficiency, and collector inlet velocity all peaking at an outer chimney diameter of 15.24 m (corresponding to an area ratio of 2.25). At this configuration, power generation increases to 75.91 kW, approximately 1.5 times more than the initial design. Remarkably, at a low collector inlet height of 0.2 m, combining it with a chimney diameter of 4.5 times the chimney inlet diameter (4.5dch) results in an impressive power output of 635.02 kW, signifying a substantial 12.45-fold increase. To model the performance under these diverse conditions, an artificial neural network (ANN) is effectively utilized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

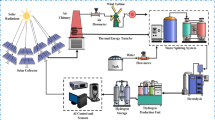

A solar chimney (SC) power plant is a device designed for harnessing solar energy to generate power. It consists of three primary components: the collector absorber plate, a transparent cover, and a chimney. Energy conversion takes place from thermal to kinetic energy and finally into electricity1,2,3,4. Despite the simplicity in construction and principle, several issues exist, mostly the low efficiency of the plant. Apart from the material of the transparent cover and absorber plate, geometric parameters like collector diameter, collector inlet, chimney height, chimney diameter, and divergence influence the performance5. So far, the first plant is reported in Spain (Manazaranes) by Haaf et al.6,7 in 1982 for generating ~ 50 kW power. The study on the variation of collector inlet (Table 1), variation of chimney diameter (Table 2), and divergence (Table 3) are listed in detail.

The above study of collector inlet variation envisages that the flow velocity rises but the flow volume drops for the reduction of inlet height. Several studies have mentioned the rise in power for a small inlet. However, a very small height weakens the flow and, consequently power generation. Very few of the studies have addressed optimum inlet height; this height is different for different sizes of plants. From the effect of chimney diameter, it can be claimed by a few studies that velocity rises for small chimney diameters and power rises, as power is proportional to velocity. Most of the researchers have addressed the rise in power with a rise in chimney diameter. This augments suction pressure and flow volume. However, a very high chimney diameter chokes the flow, as mentioned by a few studies. The optimum diameter depends on chimney height, measured by the slenderness ratio. Its value is 5–626, 6–827. Balijepalli et al.28 have mentioned the significance of the chimney height to collector diameter (dg) ratio since the performance of the plant depends on this ratio. Many of the studies have been carried out without the optimum value of diameter. The divergence study claims that suction rises but there is also an optimum divergence angle or area ratio. This is different for different models, any new models require this study. Azad et al.29 have worked numerically towards the optimization of design parameters (collector height and diameter, chimney height and diameter) of solar chimneys with desalination plants by using neural networks for power generation and freshwater production. The numerical work of Xu et al.30 shows an improvement in power generation up to 120kW by incorporating an energy storage layer for the Spanish prototype. Zhou31 has studied the thermal performance of curved sloped collectors on two segmental slopes and compared it with two linearized rising slopes.

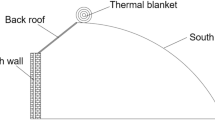

The construction of the Manzaranes plant was an inspiration to start innovative research. Considering this plant, the chimney height and how it influences the plant performance for increasing chimney height is investigated by many researchers32,33,34,35. The optimal chimney height lengthens as the collector diameter rises36. The impact of collector slant and diameter is also investigated32,37,38,39,40,41,42. A sloped collector enhances the performance of the plant apart from the collector diameter. The collector roughness is also scrutinized to obtain better effectiveness43,44. Few studies, considering heat storage45, using radiation and real model46,47,48, using chimney entry fillets49, and 2D study50,51,52 have also been noted for the same plant.

Numerous researchers have dedicated their efforts to advancing cleaner energy production, with a particular focus on enhancing the performance of solar chimney (SC) plants. While extensive work has been conducted within the field, the review of existing literature reveals a noticeable gap in the optimization of collector inlet heights. Few researchers have explored this avenue, despite its potential impact on SC plant performance. On the other hand, investigations regarding the optimization of chimney diameter and divergence have received greater attention, primarily to maximize power generation4,14,29,30,31. However, when it comes to the classical Manzanares SC plant, the examination of optimal collector inlet height and chimney diameter remains notably limited. This uncharted territory within the realm of thermo-fluid flow phenomena within the SCPP, including collector inlet height and chimney diameter, has provided the impetus for our novel approach, taking on the challenge of improving SC plant performance. Our study is aimed at optimizing the standard Manzanares SC plant by altering the collector inlet (hi), chimney diameter (dch), and chimney divergence based on the exit diameter (do). Furthermore, it involves a comparative thermal assessment of the Manzanares SC plant under various geometric constraints, spanning key parameters such as collector inlet (hi = 1.85 to 0.1 m), chimney inlet diameter (10.16 to 55.88 m or 1.0dch to 5.5dch), and chimney outlet diameter (10.16 to 30.48 m or 1.0dch to 3dch). The outcomes of our analysis are presented in the form of fluid flow and temperature distributions, encompassing pressure, velocity, temperature, and mass flow, as well as performance parameters including power and efficiencies. Additionally, we have endeavored to construct a performance model using an artificial neural network (ANN), a valuable tool that can greatly assist designers in the creation of prototypes.

Methodology and analysis

Formation of physical domain

In the present analysis, the well-known Manzanares unit6 is selected as the basic model as depicted in Fig. 1. For the investigation of the SC model, it is supposed that the ambient air is incompressible and surrounding ambient conditions have no change with time. Here, the density variation at low temperatures is taken care of by following the Boussinesq method. Furthermore, the solar radiation of 103 W/m2 is supposed to be constant during each process53.

Governing equations and modeling

The transport equations for the flow model of the SC plant consist of mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations, which are solved numerically by applying the proper boundary conditions. These equations54, 55 are presented (in the tensor form) as:

where the indices i and j indicate 1, 2, and 3, respectively), Pr and σt are the Prandtl number and turbulent Prandtl number. The buoyant force is expressed as ρβgiΔT in Eq. (2). The symbols μ and μt in Eqs. (2) and (3) correspond to the laminar and turbulent viscosity, respectively. The qrad stands for radiative heat flux obtained by solving the radiative transfer equation (RTE) given later in Eq. (6). The Kronecker delta is expressed by the symbol δ (wherever δ = 1, while i = j and else δ = 0).

In the present study, the fluid flow remains in a turbulent flow regime. The RNG \(k - \varepsilon\) turbulence model equations33,56,57,58,59 are given by

Different terms in RNG \(k - \varepsilon\) turbulence model equations are shown in Table 4.

In the study, the ANSYS-Fluent 18.1 solver, in combination with the validated Discrete Ordinates (DO) model for radiation transport41,43,58, was employed. The DO model discretizes angular space into discrete angles, facilitating directional radiation analysis and numerical determination of radiation intensity (I). The radiative transfer equation (RTE), as presented in Eq. (6), mathematically describes solar radiation transport within the medium, taking into account phenomena such as absorption, emission, scattering, and phase functions. The RTE predicts the distribution of radiation intensity and the resulting radiative heat flux within the computational domain. This flux serves as a critical source term (qrad) in the energy equation, described in Eq. (3), which considers energy transport mechanisms including convection, conduction, and radiation. ANSYS-Fluent seamlessly integrates the RTE, DO model, and their coupling with the energy equation, ensuring accurate radiation simulations within the Solar Chimney Power Plant (SCPP).

The radiative transfer equation is expressed as

where \(\vec{s}^{\prime}\) and \(\sigma_{s}\) denote scattering vector and coefficient, \(a\) absorption coefficient, m refractive index, \(\varphi\) phase function, \(\Omega^{\prime}\) solid angle, and I radiation intensity (in W/m2).

The impact of different geometric parameters on the effectiveness of the SC plant is examined through power production, collector efficiency, and overall efficiency4. Here, the actual power generation is estimated as

In the above equation, the symbols \(\eta_{t}\) correspond to the turbine efficiency, which is taken as 0.841, \(\Delta p\) is the pressure drop in the turbine, which is calculated as the average pressure at the chimney base (CB) \(\times\) the pressure drop ratio (the general value is 2/3)60.

Airflow at CB, Q = chimney area \(\times\) air velocity at CB.

where \(m_{a}\) = air flow at CB, kg/s, Cp = specific heat of air, kJ/kgK, \(T_{CB}\) = air temperature at CB, K, \(A_{coll}\) = collector area, m2, \(I\) = irradiation, W/m2.

Numerical technique

Solution methodology

In this study, the involved transport equations are solved numerically using the finite volume-based ANSYS-Fluent 19.2 solver59. The model was generated following the axisymmetric CFD model. Finally, part of the complete model (vertical slice of 15° model) is taken for the computations to reduce the total cost of computations. A similar approach has also been followed by many researchers. For instance, Hassan et al.21 have considered the 180° model, whereas the 90° and 5° model has been considered by Cuce et al.25, and Koonsrisuk and Chitsomboon17 respectively. The chosen computational model along with the appropriate boundary conditions are solved in an iterative process applying the SIMPLE algorithm, which couples the pressure and velocity. Thereafter, the second-order upwind scheme is applied to discretize the pressure, momentum, and energy equations. The computational domain is divided into smaller grids. The grids are distributed nonuniformly to capture the correct boundary layers. The maximum Y + value in the first cell is taken as 3038 and the standard wall function is used in the mesh generation. In general, the finer meshes are distributed adjacent to the solid walls. In order to obtain the converged solution, an iterative process is continued till the reduction of the residuals until 10–6 for all the governing equations61,62,63. The corresponding solution procedure is demonstrated in a flow chart, which is shown in Fig. 2.

The adopted boundary conditions for the present study geometry are listed in Table 5. After the mesh independence study, a mesh of 73,862 for the element size 0.80 is taken into consideration for the present analysis. Mesh study is accomplished through different element sizes by comparing the various local parameters such as maximum velocity, temperature, chimney base velocity and temperature, and mass flow rate considering the Manzaranes plant. The considered element sizes taken as 0.90, 0.85, 0.80, 0.75, and corresponding meshes are 53,883 (M1), 62,021 (M2), 73,862 (M3), and 85,551 (M4), respectively. From the comparison, it is observed that the cumulative error level for the different local variables in the consecutive grids decreases with the decreasing element size. Furthermore, the change between element sizes 0.8 and 0.75 is much less. With this comparison, 0.8 element size (M3) is finalized for the extensive study without further increasing computational time for the study. In fact, for obtaining the converged and stable solution under all the parametric variations, a minimum convergence criterion of 10–6 for the maximum residuals and the mass defect is chosen for the computation.

Validation of present study

The validation study of the present solver is examined by comparing the CB velocity and power (in kW), as shown in Fig. 3, which confirms the accuracy level of the present solver.

Discussion of results

This work attempts to enhance the power production of the classical Manzanares SC plant by modifying the collector inlet height, chimney diameter, and its divergence to obtain the best design of the plant. Comparative thermal performance assessment of Manzaranes solar chimney (SC) power plant by different geometries is the main aim of this study. The specified geometries are collector inlet heights (hi), chimney diameter (dch), and chimney divergence by chimney outlet diameter (do). The performance assessments are conducted for the range of key controlling geometric parameters like collector height (1.85 to 0.1 m), chimney diameter (10.16 to 55.88 m i.e. 1.0dch to 5.5dch), and chimney outlet diameter (10.16 to 30.48 m i. e., 1.0dch to 3.0dch). The outcomes of the analysis are presented through the fluid flow and temperature distributions (namely pressure, velocity, temperature, and mass flow) and performance parameters (power, collector, and overall efficiency). Furthermore, an attempt has been made to use an artificial neural network (ANN) for developing the generalized performance model, which could be very helpful for the designer for any prototype design.

Impact of collector inlet heights (hi)

The Manzaranes plant uses a collector inlet height of 1.85 m (model, M-1). However, the present study represents the impact of collector inlet height (hi) reduction from 1.85 to 0.1 m systematically, which is defined by the different models, M-1 to M-11 (in Table 6). This analysis computes inlet velocity, chimney base velocity, pressure, temperature, mass flow rate, power produced, collector efficiency, and overall efficiency.

Flow parameters assessment

The induced buoyancy force in-between the collector and absorber plate begins the fluid flow velocity at the collector inlet, the study of the inlet velocity assists the thermo-fluid flow analysis for the plant. The impact of the reduction of collector inlet height (hi) is illustrated in Fig. 4. The reduction of height lessens the effective fluid flow area which in turn reduces the involved fluid flow volume. At lower flow volume, due to higher thermal energy exchange to air, the reduction of collector inlet height grows the inlet fluid velocity. This has been noticed from the collector inlet of 1.85 to 0.2 m (Model, M-1 to M-9). It is mostly owing to the reduction of flow area. Further reduction in the collector inlet height (hi) lowers the magnitude of inlet flow velocity up to model, M-11. The lower flow volume does not extract whole thermal energy and at the same time, the rise in flow velocity raises the viscous force, which is the reason for the dropping of inlet velocity despite decreasing flow area at lower collector inlet height. Therefore, the selection of a collector inlet plays a significant role in improving thermo-fluid flow properties. A reduction of collector inlet height is beneficial but much reduction is not effective. In this Manzaranes plant, the inlet height of 0.2 m (M-9) shows an optimum value for achieving the maximum flow velocity. For the fixed solar irradiation intensity, the absorber area primarily induces the inlet flow velocity at the collector inlet. Therefore, there should be some relationship between collector diameter and collector inlet height, here the value is about 1220 as observed in Table 6.

The impact of a reduction in collector inlet height (hi) on the CB flow and temperature distribution is illustrated in Fig. 5. The chimney base is taken as a reference to present the flow parameters as the air turbine is installed near the CB. Chimney base velocity drops as the collector inlet height (hi) decreases (in Fig. 5a). The drop in chimney base velocity is sharp after model, M-9. As the chimney area is constant, the volume flow rate through the chimney drops. This drop in the working flow volume in the chimney reduces the collector inlet height (hi). The drop in the flow volume is high after the reduction in the collector inlet for the model, M-9, which is due to the inlet flow velocity drop. The reduction of flow volume gains more thermal energy from the ground plate which results in high temperature as the collector inlet drops. This has been noted in Fig. 5a. With the reduction in flow volume with collector inlet reduction, the suction pressure at the chimney base is noted to rise in Fig. 5b. The temperature of air rises, which in turn reduces the density of air with the reduction of collector inlet. Same time volume flow rate drops, therefore mass flow rate drops as the collector inlet drops (Fig. 5b). The flow contour study by velocity, pressure, and temperature near the CB are illustrated in Fig. 6 for the different models, M-1(hi = 1.85 m) and M-11 (hi = 0.1 m). It is evident in the figure, that the chimney base velocity and pressure drop and chimney base temperature rise due to the reduction in the collector inlet (hi).

Performance assessment

Under the various geometric parameter variations, the performance study is examined by calculating the power generation and efficiencies (Pact, ηc, ηo), which are shown in Fig. 7. The produced kinetic energy in the air produces turbine power. This turbine work depends on the flow velocity of impinging and pressure drops through the turbine. Previous Sect. “Flow parameters assessment” shows the dropping in the velocity as collector inlet height (hi) drops tends to decrease the power generation by an air turbine. However, the increase in the suction pressure for reduction in the inlet area assists more power generation (Pact). The combined effect of velocity and pressure on power generation by the turbine shows the rising tendency of power and the power reaches 117.42 kW at hi = 0.2 m. This power generation is 2.3 times of the classical Manzaranes plant. Further reduction of hi lessens the power generated by the turbine (as in Fig. 7a). This can be attributed to that increased power is dominated by the sudden velocity drop in spite of a better pressure drop. Moreover, it can be noted that the power generation by the turbine after hi = 0.2 m is having greater value than the Manzaranes plant. The collector efficiency (ηc) drops with decreasing inlet flow area due to the reduction of mass flow rate despite of increasing temperature of air (as in Fig. 7b). The overall efficiency (ηo) shows a similar trend of curve like power (as in Fig. 7b). The efficiency increases to 0.25%. It is also 2.3 times more compared to the Manzaranes plant. Therefore, this exercise clearly shows that collector inlet height (hi) reduction has a positive role in enhanced power generation compared to the classical Manzaranes plant.

The above study summarizes that power developed by the turbine is always higher relative to the Manzaranes plant at less hi. Maximum power lies at hi = 0.2 m, Pact = 117.42 kW. The maximum efficiency occurs at the same location, which is 0.25%. Therefore, there is no hike in the cost but power rises from 51 to 117.42 kW. As hi reduces, the chimney base velocity drops, suction pressure increases, the temperature rises, and mass flow drops.

Impact of chimney diameter (d ch)

The impact of chimney diameter (dch) is carried out by raising the chimney diameter (dch) of the Manzaranes plant up to 55.18 m (5.5dch), details of different models are listed in Table 7 from M-12 to M-20. Like earlier, flow and performance are computed and illustrated subsequently.

Flow parameters assessment

The increase in the chimney diameter (dch) shows (as in Fig. 8) the enhancement of inlet collector flow velocity, this means the increase in the flow volume, may be due to the rising in the chimney draft. It is interesting to note that the collector inlet velocity does not rise more after 4.5dch (M-18). Further rise in diameter stagnates the flow volume.

Figure 9 depicts the drop in the CB velocity (in Fig. 9a) as the chimney diameter enlarges. Here, in spite of the increase in the flow volume of air, velocity lessens, which is due to the rise in the chimney flow area. This high flow volume with rising chimney diameter reduces the temperature of the air. This, in turn, decreases the CB pressure as depicted in Fig. 9b. In spite of a drop in the CB velocity, the mass flow rises because of higher air density and higher flow chimney area. The rise in mass flow rate is not too much after the chimney diameter of 45.72 m (4.5dch, M-18). The pressure, velocity, and temperature contours at the chimney base (for dch of 10.16 m and 55.88 m) in Fig. 10 illustrate a clear understanding of flow features that velocity and temperature drops and suction pressure at the CB decrease for the model, M-20.

Performance assessment

The power generation and efficiencies variation for the different chimney inlet diameter (dch) is presented in Fig. 11. Earlier, it is depicted that the CB base velocity, and suction pressure both drop as dch rises. Both the phenomenon is against the rise in flow energy by the turbine. But the power produced (Pact) by the turbine rises as observed from Fig. 11a, which is due to the dominancy of the chimney area, this, in turn, heightens the huge flow volume of air. This enhancement of flow becomes stagnant after the chimney diameter of dch = 45.72 m (model, M-18), it results in no significant rise in the power generation further with the chimney diameter. The maximum power generation is Pact = 209 kW which is ~ 4 times than the Manzaranes plant. However, it should be mentioned that some extra cost is required to obtain this increasing diameter of the chimney. The collector efficiency (in Fig. 11b) rises as dch rises for the mass flow rate enhancement but this efficiency drops when the mass flow stagnates after some value of chimney diameter. The nature of variation of overall efficiency follows the same trend line as power (in Fig. 11b). The efficiency rises to 0.44% in this case.

From this analysis, it is to be noted that the maximum power available at dch = 45.72 m for the slenderness ratio of 4.25. The earlier study depicts the value as 5–624, and 6–825 for the different model plants. The power produced is far more than the power generation at a lower hi though it involves cost.

Impact of chimney divergence (d o)

In this section, the effect of chimney divergence (do) on the performance of the SCPP model is exercised. Here the chimney divergence is made by changing the chimney outlet diameter (do) as mentioned in Table 8, the chimney inlet diameter (dch) is made constant of 10.16 m. The variation of models, M-21 to M-24 for the chimney outlet diameter of 30.48 m, which is 3.0dch, and the corresponding area ratio of 9.0. A similar flow and performance analysis is carried out to present the comparative results with the reduction of inlet height (hi) and rise in the chimney diameter (dch).

Flow parameter assessment

From the collector inlet velocity variation (as in Fig. 12), it is observed that the increase in outer diameter, do of 15.24 m (1.5 dch) from the base diameter of 10.16 m enhances the flow velocity. This may lead to a rise in the suction pressure by the chimney, which in turn increases the mass flow rate. This collector inlet velocity drops further rise in the chimney outlet diameter, which may be due to the higher pressure loss in the chimney. Therefore, the area ratio of 2.25 is the optimum value to obtain the maximum inlet flow velocity. The study of CB velocity, pressure, temperature, and mass flow is illustrated for the considered chimney divergence models M-21 to 24 as shown in Fig. 13. As hi and dch are fixed, the same pattern of flow velocity is observed. The magnitude of velocity is different for different areas. Due to the nozzle action, suction pressure rises, mass flow rises and the corresponding air temperature drops at do = 1.5dch. Further, increase in the divergence, suction pressure drops less which lessens the mass flow rate, however, the air temperature rises as depicted. The flow contours are illustrated for do of 10.16 m, 15.24 m, and 30.48 m (1.0dch, 1.5 dch and 3.0dch) in Fig. 14. It reveals the optimum velocity, pressure, and temperature at chimney outlet diameter of 15.24 m.

Performance assessment

This study reveals the power generation and efficiencies variation for the different chimney inlet diameters (dch), all having an optimum value at 15.24 m (Area ratio: 2.25) outer chimney diameter (as shown in Fig. 15). Earlier studies reveal the area ratio of 10.020, 4.025. Here, the power generation rises to 75.91 kW, which is ~ 1.5 times more than the Manzaranes plant, corresponding efficiency is 0.16%. Comparing the effect of hi and dch, the impact of divergence is not effective and it requires some additional cost.

Combined effect of collector inlet (h i) and chimney diameter (d ch)

The aforesaid comparative assessment for a reduction in collector inlet height (hi), rise in chimney diameter (dch), and chimney divergence (do) shows the performance improvement of the solar chimney power plant. The lowering of chimney inlet height (hi) does not require any hike in the initial investment cost, whereas the chimney diameter (dch) and divergence (do) need a rise in the initial installation cost. The power generation rise is more for a reduction in hi and rises in the chimney diameter dch. Therefore few models are chosen for the study at hi of 0.2 m and for different chimney diameters, 5.08 m to 45.72 m (0.5dch to 4.5dch), as shown in Table 9 to study the superior performance of the SCCP. The remarkable power rise has been noted as illustrated in Fig. 16. At a lower value of hi of 0.2 m, the power generation with a chimney diameter of 1.5 dch is 216.18 kW (which is 4.23 times of the Manzaranes plant), 2.0 dch is 331.22 kW (which is 6.49 times of the Manzaranes plant), 2.5 dch is 444.40 kW (which is 8.71 times of the Manzaranes plant), 3.0 dch is 562.89 kW (which is 11.03 times of the Manzaranes plant), 3.5 dch is 608.99 kW (which is 11.94 times of the Manzaranes plant), 4.0 dch is 627.7 kW (which is 12.3 times of the Manzaranes plant), 4.5 dch is 635.02 kW (which 12.45 times of the Manzaranes plant). Therefore, it summarizes that this combined model could be an alternative design for performance improvement,

Artificial neural network (ANN) for performance analyses

Today’s, artificial neural networks (ANN) play an important role in predicting the outputs. An application of artificial neural networks has been noted in solar heating systems66,67. The performance of the Solar chimney power plant is predicted by Amirkhani et al.68, Fadaei et al.69. A significant number of inputs and outputs are required in order to create an ANN model. In the present study, ANN is used to predict the flow and performance parameters by using input data such as collector inlet height (hi), chimney diameter (dch), and chimney divergence (do). Chimney height, collector diameter, and solar intensity remained constant. The output variables are inlet velocity (Vi), chimney base velocity (VCB), chimney base temperature (TCB), chimney base pressure (pCB), mass flow rate (ma), Power generation (Pact), collector efficiency (ηc) and overall efficiency (ηo). The general architecture of the three layers of ANN is shown in Fig. 17. The 1st layer is the input layer, the 2nd layer is the hidden layer, and 3rd layer i.e. the last layer is the output layer. Each neuron in the hidden layer is assigned weight (WIj) and bias (Bj). Each neuron in the output layer is assigned weight (WjO) and bias (BO). In our design, the input layer consists of three neurons namely, I1(hi), I2(dch), and I3(do), and the output layer consists of eight neurons namely, O1(Vi), O2(VCB), O3(TCB), O4 (pCB), O5(Pact), O6 (ma), O7(ηc), and O8(ηo).

Forward and backward propagation

The forward propagation method works on the input layer to the hidden layer and the hidden layer to the output layer. This method is used to calculate the output of each neuron in the hidden layer and output layer70, 71. It starts operation by initializing a random weight and bias. Then calculates the output of each neuron in the hidden and output layers using the activation function. There are different types of activation functions such as Thresholds, Sigmoid, Tanh, ReLu, and tansig. Here we used the tansig activation function to calculate the output in the hidden and output layers. The activation function (tansig) is given below:

where \(z = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n} {I_{i} } W_{i} + B\), with I is the input values, W is the transpose of the weight between input and hidden layers and B is the bias vector in a different layer. Using the above equation we can predict output from the output layer. Now at each output, the error will be calculated using the following formula:

If the error is large then we use the backward propagation method to correct the weights. The backward propagation method works in the output layer to the hidden layer and the hidden layer to the input layer. In different layers weights are updated using the following equation:

where λ is the learning rate of the design, which signifies how quickly the design predicts the target output. W is the weight vector in different layers. So using the above equation weights will be updated by the backward propagation method.

Determination of the number of neurons in the hidden layer

To design an efficient neural network, it is necessary to know the number of neurons in the hidden layer. The following flowchart (as shown in Fig. 18) is utilized to determine the number of neurons in the hidden layer.

To determine the number of neurons in the hidden layer, we have calculated mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), relative square error (RSE), and correlation coefficient (R2). The following formulas are used for the calculation of various error parameters.

where n is the total number of data sets, \(y_{{{\text{true}}}}\) is the actual (target) output, \(\overline{{y_{{{\text{true}}}} }}\) is the mean of the actual (target) output, and \(y_{train}\) is the ANN output (predicted) after training the model. We have plotted the MSE, RMSE, RSE, and R2 with different values of the number of neurons in the hidden layer as shown in Fig. 19. Our goal is to find the number of neurons for which MSE, RMSE, and RSE are minimum and correlation coefficient close to 1. To ascertain the optimal number of neurons for our hidden layer, we relied on a flowchart (Fig. 18) and computed various error metrics, including MSE, RMSE, RSE, and R2 (Eqs. 13–16). We aimed to identify the neuron count that simultaneously minimized MSE, RMSE, and RSE while maximizing R2. As depicted in Fig. 19, the hidden layer comprising 43 neurons exhibited the most favorable outcomes, yielding the lowest values for MSE, RMSE, and RSE (approximately 0.000430737, 0.02075421, and 2.645358 × 10–15, respectively). Additionally, the correlation coefficient approached 1 (0.9999993). As a result, we proceeded to create a network with a hidden layer comprising 43 neurons.

Network design and predicted results

Now we have designed the artificial neural network with 43 neurons in the hidden layer. To mitigate overfitting, we partitioned our dataset into three segments: the test set, the training set, and the validation set. The validation set played a pivotal role in monitoring our model's performance during training. If the model performs well on the training set but poorly on the validation set, it may be overfitting. We have trained the neural network using the training dataset. To reduce error, the network’s weight function is corrected by the back propagation method. The validation dataset is used to calculate network generalizations, and we stopped training when generalizations did not improve. With the use of the testing dataset, the network’s performance is assessed both during and after training. In this approach, the training process uses 85% of the whole data set, testing uses 10% of the data set, and assessing network performance uses the remaining dataset. The change of MSE for training, validation, and testing data sets with the number of epochs is depicted in Fig. 20. Figure 20 shows that the best validation performance, 2.999 × 10–5 at epoch 73, was achieved. We stopped the training process after epoch 73 because the number of iterations increased and the errors increased, which may indicate overfitting.

Figure 21 displays the error for various data sets (training, validation, testing, and overall). The results show that the error factor is closer to 1, demonstrating the neural network's ability to fully associate the input data set with the model data set. The values error in the training data set, validation data set, test dataset, and overall data set are 0.99983, 0.999451, 0.99934, and 0.99962 respectively. This shows that the results are reasonably good for the designed neural network.

With this trained network, we have now calculated expected output values for several data sets. Figure 22 displays the distribution of goals and anticipated values at the outputs O1, to O8 for several data sets.

It can be seen from the aforementioned Fig. 22 that the 43 neurons constructed neural network accurately predicts the output values. Therefore, we may anticipate output values for an unknown data set using this trained neural network.

To predict the developed power (Pact) of SCPP as a function of collector inlet height (hi), chimney inlet diameter (dch), and chimney outlet diameter (do) for the constant collector diameter and same irradiation, regression analysis has been carried out using MATLAB code with the inbuilt function of nlinfit. The correlation is expressed as

where the variables an are given as a1 − 201.8916679297755, a2 − 131.9161514753086, a3 14.0151979342754, a4 − 11.4489669355259, a5 − 5.2534078301303, a6 8.8785124787426, a7 0.9090599083684, a8 316.7444829699626, a9 − 0.1564657170176, a10 − 0.3274118939252.

Conclusion

This work attempts for enhancing the power generation of the classical Manzanares solar chimney (SC) plant by modifying the collector inlet height, chimney diameter, and its divergence to obtain the best design of the plant. The performance assessment is evaluated for the different combinations of specified geometric parameters like collector inlet (hi), chimney diameter (dch), and chimney divergence by exit diameter (do). The outcomes of the analysis are presented through the local distributions (pressure, velocity, temperature, mass flow) and performance parameters (power generation and efficiencies). Furthermore, an attempt has been made to utilize an artificial neural network (ANN) for developing the performance model, which could be very helpful for the designer of the prototype design.

This study reveals that the power developed by the turbine rises always at the lowering collector inlet height of the classical Manzaranes plant. The maximum power lies at hi = 0.2 m, which is Pact = 117.42 kW. The maximum efficiency occurs at the same location, which is 0.25%. Therefore, the power generation rises from 51 kW to 117.42 kW (~ 2.3 times) without increasing any additional installation cost. As hi reduces, the chimney base velocity drops, suction pressure increases, the temperature rises, and mass flow drops. The optimum collector inlet velocity occurs at hi = 0.2 m.

A rise in the chimney diameter (dch) lowers the chimney base velocity, and suction pressure, both. In spite of these, the power generation by the turbine rises, and the flow becomes stagnant after the chimney diameter of 45.72 m (corresponding slenderness ratio: 4.5). No significant alteration in the collector inlet velocity is noted after this diameter. The maximum power generation at this chimney diameter is 209 kW, which is ~ 4 times than the Manzaranes plant, corresponding efficiency is 0.44%. However, this rise in the chimney diameter requires a higher initial investment cost.

The study on chimney divergence reveals that the power production, collector as well as overall efficiency, and collector inlet velocity, all have an optimum value at 15.24 m (area ratio: 2.25) outer chimney diameter. Then, the power generation rises to 75.91 kW which is ~ 1.5 times more than the Manzaranes plant, the corresponding efficiency is 0.16%.

At a lower hi of 0.2 m, the power generation with the chimney diameter of 1.5 dch is 216.18 kW, 2.0 dch is 331.22 kW, 2.5 dch is 444.40 kW, 3.0 dch is 562 kW, 3.5 dch is 608.99 kW, 4.0 dch is 627.7 kW, 4.5 dch is 635.02 kW (12.45 times of Manzaranes plant).

An artificial neural network (ANN) is utilized for developing performance modeling to predict the output parameters.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A ch :

-

Chimney area, m2

- A coll :

-

Area of collector, m2

- c p :

-

Specific heat of air, kJ/kgK

- d ch :

-

Chimney diameter, m

- h i :

-

Inlet height of collector

- d c :

-

Diameter of collector, m

- d g :

-

Diameter of ground, m

- d o :

-

Chimney exit diameter, m

- h ch :

-

Chimney length, m

- Gr:

-

Grashof number

- I :

-

Solar irradiation, W/m2

- L :

-

Characteristic length, m

- m a :

-

Mass flow rate, kg/s

- p :

-

Pressure, Pa

- Pr:

-

Prandtl number

- Q :

-

Volume flow rate, m3/s

- Ra:

-

Rayleigh number

- T :

-

Temperature, K

- V :

-

Velocity, m/s

- P act :

-

Electrical power developed by generator, W

- u i :

-

Velocity vector, m/s

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Thermal diffusivity, m2/s

- \(\beta\) :

-

Thermal expansion coefficient, 1/K

- \(\mu\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity, kg/ms

- \(\nu\) :

-

Kinematic viscosity, m2/s

- \(\eta_{c}\) :

-

Collector efficiency, %

- \(\eta_{o}\) :

-

Overall efficiency, %

- \(\rho_{air}\) :

-

Ambient air density, kg/m3

- c :

-

Collector

- ch :

-

Chimney

- CB :

-

Chimney base

- eff :

-

Efficiency

- in :

-

Inlet

- o :

-

Overall

- out :

-

Outlet

References

Pradhan, S., Chakraborty, R., Mandal, D. K., Barman, A. & Bose, P. Design and performance analysis of solar chimney power plant (SCPP): A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101411 (2021).

Mandal, D. K., Pradhan, S., Chakraborty, R., Barman, A. & Biswas, N. Experimental investigation of a solar chimney power plant and its numerical verification of thermo-physical flow parameters for performance enhancement. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 50, 101786 (2022).

Das, P. & Chandramohan, V. P. A review on solar updraft tower plant technology: Thermodynamic analysis, worldwide status, recent advances, major challenges and opportunities. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 52, 102091 (2022).

Biswas, N., Mandal, D. K., Bose, S., Manna, N. K. & Benim, A. C. Experimental treatment of solar chimney power plant—A comprehensive review. Energies 16, 6134 (2023).

Mehranfar, S. et al. Comparative assessment of innovative methods to improve solar chimney power plant efficiency. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 49, 101807 (2022).

Haaf, W., Friedrich, K., Mayr, G. & Schlaich, J. Solar chimneys part I: Principle and construction of the pilot plant in manzanares. Int. J. Sol. Energy 2(1), 3–20 (1983).

Haaf, W. Solar chimneys part II: Preliminary test results from the manzanares pilot plant. Int. J. Sol. Energy 2(2), 141–161 (1984).

Kasaeian, A., Ghalamchi, M. & Ghalamchi, M. Simulation and optimization of geometric parameters of a solar chimney in Tehran. Energy Convers. Manag. 83, 28–34 (2014).

Patel, S. K., Prasad, D. & Ahmed, M. R. Computational studies on the effect of geometric parameters on the performance of a solar chimney power plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 77, 424–431 (2014).

Vieira, R. S. et al. Numerical study of the influence of geometric parameters on the available power in a solar chimney. Eng. Térmica Therm. Eng. 14(1), 103–109 (2015).

Ghalamchi, M., Kasaeian, A., Ghalamchi, M. & Mirzahosseini, A. H. An experimental study on the thermal performance of a solar chimney with different dimensional parameters. Renew. Energy 91, 477–483 (2016).

Toghraie, D., Karami, A., Afrand, M. & Karimipour, A. Effects of geometric parameters on the performance of solar chimney power plants. Energy 162, 1052–1061 (2018).

Yapici, E. Ö., Ayli, E. & Nsaif, O. Numerical investigation on the performance of a small scale solar chimney power plant for different geometrical parameters. J. Clean. Prod. 276, 122908 (2020).

Golzardi, S., Mehdipour, R. & Baniamerian, Z. How collector entrance influences the solar chimney performance: Experimental assessment. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 146, 1–14 (2020).

Ming, T., Derichter, R. K., Meng, F., Pan, Y. & Liu, W. Chimney shape numerical study for solar chimney power generating systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 37(4), 31022 (2013).

Cottam, P. J., Duffour, P., Lindstrand, P. & Fromme, P. Solar chimney power plants—Dimension matching for optimum performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 194, 112–123 (2019).

Koonsrisuk, A. & Chitsomboon, T. Effects of flow area changes on the potential of solar chimney power plants. Energy 51, 400–406 (2013).

Okada, S., Uchida, T., Karasudani, T. & Ohya, Y. Improvement in solar chimney power generation by using a diffuser tower. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 137, 031009–031011 (2015).

Ohya, Y., Wataka, M., Watanabe, K. & Uchida, T. Laboratory experiment and numerical analysis of a new type of solar tower efficiently generating a thermal updraft. Energies 9(12), 1077 (2016).

Hu, S., Leung, D. Y. C. & Chan, J. C. Y. Impact of the geometry of divergent chimneys on the power output of a solar chimney power plant. Energy 120, 1–11 (2017).

Hassan, A., Ali, M. & Waqas, A. Numerical investigation on performance of solar chimney power plant by varying collector slope and chimney diverging angle. Energy 142, 411–425 (2018).

Nasraoui, H., Driss, Z., Ayadi, A., Bouabidi, A. & Kchaou, H. Numerical and experimental study of the impact of conical chimney angle on the thermodynamic characteristics of a solar chimney power plant. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. E J. Process. Mech. Eng. 233(5), 1185–1199 (2019).

Das, P. & Chandramohan, V. P. 3D numerical study on estimating flow and performance parameters of solar updraft tower (SUT) plat: Impact of divergent angle of chimney, ambient temperature, solar flux and turbine efficiency. J. Clear. Prod. 256, 120353 (2020).

Das, P. & Chandramohan, V. P. Performance characteristics of divergent chimney solar updraft tower plant. Int. J. Energy Res. 45, 1–16 (2020).

Cuce, E. et al. Performance assessment of solar chimney power plants with the impacts of divergent and convergent chimney geometry. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 16, 704–714 (2021).

Pretorius, J. P. Optimization and Control of a Large-Scale Solar Chimney Power Plant (University of Stellenbosch, 2007).

Kashiwa, B. A. & Kashiwa, C. B. The solar cyclone: A solar chimney for harvesting atmospheric water. Energy 33(2), 331–339 (2008).

Balijepalli, R., Chandramohan, V. P. & Kirankumar, K. Development of a small scale plant for a Solar chimney power plant (SCPP): A detailed fabrication procedure, experiments and performance parameters evaluation. Renew. Energy 148, 247–260 (2020).

Azad, A., Aghaei, E., Jalali, A. & Ahmadi, P. Multi-objective optimization of a solar chimney for power generation and water desalination using neural network. Energy Convers. Manag. 238, 114152 (2021).

Xu, G., Ming, T., Pan, Y., Meng, F. & Zhou, C. Numerical analysis on the performance of solar chimney power plant system. Energy Convers. Manag. 52, 876–883 (2011).

Zhou, X. Thermal performance of curved-slope solar collector. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 150, 119295 (2020).

Li, J. Y., Guo, P. H. & Wang, Y. Effects of collector radius and chimney height on power output of a solar chimney power plant with turbines. Renew. Energy 47, 21–28 (2012).

Fard, K. P. & Beheshti, P. H. Performance enhancement and environmental impact analysis of a solar chimney power plant: Twenty-four-hour simulation in climate condition of Isfahan province, Iran. Int. J. Eng. 30, 1260–1269 (2017).

Shahi, D. V. V., Gupta, A. & Nayak, V. S. CFD analysis of solar chimney wind power plant by Ansys Fluent. Int. J. Technol. Res. Eng. 5(9), 3746–3751 (2018).

Cuce, E., Sen, H. & Cuce, P. M. Numerical performance modelling of solar chimney power plants: Influence of chimney height for a pilot plant in Manzanares, Spain. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 39, 100704 (2020).

Zhou, X., Yang, J., Xiao, B., Hou, G. & Xing, F. Analysis of chimney height for solar chimney power plant. Appl. Therm. Eng. 29(1), 178–185 (2008).

Cao, F., Li, H., Zhang, Y. & Zhao, L. Numerical simulation and comparison of conventional and sloped solar chimney power plants: the case for Lanzhou. Sci. World J. 852864, 1–8 (2013).

Gholamalizadeh, E. & Kim, M. H. CFD (computational fluid dynamics) analysis of a solar-chimney power plant with inclined collector roof. Energy 107, 661–667 (2016).

Cuce, E. Güneş bacası güç santrallerinde toplayıcı eğiminin çıkış gücüne ve sistem verimine etkisi. Uludağ Üniversitesi Mühendislik Fakültesi Dergisi 25(2), 1025–1038 (2020).

Cuce, P. M., Cuce, E. & Sen, H. Improving electricity production in Solar chimney power plants with sloping ground design: An extensive CFD research. J. Sol. Energy Res. Updates 7, 122–131 (2020).

Keshari, S. R., Chandramohan, V. P. & Das, P. A 3D numerical study to evaluate optimum collector inclination angle of Manzanares solar updraft tower power plant. Sol. Energy 226, 455–467 (2021).

Cuce, E. et al. Impacts of ground slope on main performance figures of solar chimney power plants: A comprehensive CFD research with experimental validation. Int. J. Photoenergy 6612222, 1–11 (2021).

Fallah, S. H. & Valipour, M. S. Evaluation of Solar chimney power plant performance: The effect of artificial roughness of collector. Sol. Energy 188, 175–184 (2019).

Elwekeel, F. N. M., Abdala, A. M. M. & Rahman, M. M. Effects of novel collector roof on solar chimney power plant performance. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 141, 031004 (2019).

Attig-Bahar, F., Sahraoui, M., Guellouz, M. S. & Kaddeche, S. Effect of the ground heat storage on solar chimney power plant performance in the South of Tunisia: Case of Tozeur. Sol. Energy 193, 545–555 (2019).

Guo, P., Li, J. & Wang, Y. Numerical simulations of solar chimney power plant with radiation model. Renew. Energy 62, 24–30 (2014).

Gholamalizadeh, E. & Chung, J. D. Analysis of fluid flow and heat transfer on a solar updraft tower power plant coupled with a wind turbine using computational fluid dynamics. Appl. Therm. Eng. 126, 548–558 (2017).

Huang, H., Zhang, H., Huang, Y. & Lu, F. Simulation calculation on solar chimney power plant system. In Challenges of Power Engineering and Environment (eds Cen, K. et al.) 1158–1161 (Springer, 2007).

Praveen, V., Das, P. & Chadromohan, V. P. A novel concept of introducing a fillet at the chimney base of solar updraft tower plant and thereby improving the performance: A numerical study. Renew. Energy 179(2021), 37–46 (2021).

Sangi, R., Amidpour, M. & Hosseinizadeh, B. Modeling and numerical simulation of solar chimney power plants. Sol. Energy 85, 829–838 (2011).

Rabehi, R., Chaker, A., Aouachria, Z. & Tingzhen, M. CFD analysis on the performance of a solar chimney power plant system: Case study in Algeria. Int. J. Green Energy 14, 971–982 (2017).

Senbeto, M. Numerical simulations of solar chimney power plant with thermal storage. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 9(10), 103–106 (2020).

Biswas, N., Mandal, D. K., Manna, N. K. & Benim, A. C. Novel stair-shaped ground absorber for performance enhancement of solar chimney power plant. Appl. Therm. Eng. 227, 120466 (2023).

Mandal, D. K., Biswas, N., Manna, N. K. & Benim, A. C. Impact of chimney divergence and sloped absorber on energy efficacy of a solar chimney power plant (SCPP). Ain Shams Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102390 (2023).

Mandal, D. K., Biswas, N., Barman, A., Chakraborty, R. & Manna, N. K. A novel design of absorber surface of solar chimney power plant (SCPP): Thermal assessment, exergy and regression analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 56, 103039 (2023).

Sudprasert, S., Chinsorranant, C. & Rattanadecho, P. Numerical study of vertical solar chimneys with moist air in a hot and humid climate. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 102, 645–656 (2016).

Abdelmohimen, M. A. H. & Algarni, S. A. Numerical investigation of solar chimney power plants performance for Saudi Arabia weather conditions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 38, 1–8 (2018).

Das, P. & Chandramohan, V. P. Computational study on the effect of collector cover inclination angle, absorber plate diameter and chimney height on flow and performance parameters of solar updraft tower (SUT) plant. Energy 172, 366–379 (2019).

Ansys Inc, ANSYS Fluent 16 Theory guide (2016).

Li, J., Guo, H. & Huang, S. Power generation quality analysis and geometric optimization for solar chimney power plants. Sol. Energy 139, 228–237 (2016).

Biswas, N., Mandal, D. K., Manna, N. K., Gorla, R. S. R. & Chamkha, A. J. Role of different geometric shapes on hydromagnetic convection of hybrid nanofluid in an umbrella-shaped porous cavity. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow https://doi.org/10.1108/HFF-11-2022-0639 (2023).

Biswas, N., Mandal, D. K., Manna, N. K. & Benim, A. C. Enhanced energy and mass transport dynamics in a thermo-magneto-bioconvective porous system containing oxytactic bacteria and nanoparticles: Cleaner energy application. Energy 263(6), 125775 (2022).

Mandal, D. K. et al. A numerical experimentation on fluid flow and heat transfer in a SCPP. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1080(1), 012027 (2021).

Schlaich, J. R., Bergermann, R., Schiel, W. & Weinrebe, G. Design of commercial solar updraft tower systems—Utilization of solar induced convective flows for power generation. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 127(1), 117–124 (2005).

Zuo, L. et al. Design and optimization of turbine for solar chimney power plant based on lifting design method of axial-flow hydraulic turbine impeller. Renew. Energy 171, 799–811 (2021).

Kalogirou, S. A. Long-term performance prediction of forced circulation solar domestic water heating systems using artificial neural networks. Appl. Energy 66(1), 63–74 (2000).

Kalogirou, S. A., Panteliou, S. & Dentsoras, A. Modeling of solar domestic water heating systems using artificial neural networks. Sol. Energy 65(6), 335–342 (1999).

Amirkhani, S., Nasirivatan, Sh., Kasaeian, A. B. & Hajinezhad, A. ANN and ANFIS models to predict the performance of solar chimney power plants. Renew. Energy 83, 597–607 (2015).

Fadaei, N., Yan, W.-M., Tafarroj, M. M. & Kasaeian, A. The application of artificial neural networks to predict the performance of solar chimney filled with phase change materials. Energy Convers. Manag. 171, 1255–1262 (2018).

Mandal, D. K. et al. Thermo-fluidic transport process in a novel M-shaped cavity packed with non-Darcian porous medium and hybrid nanofluid: Application of artificial neural network (ANN). Phys. Fluids 34, 033608 (2022).

Mondal, M. K., Biswas, N., Datta, A., Sarkar, B. K. & Manna, N. K. Positional impacts of partial wall translations on hybrid nanofluid flow in porous media: Real coded genetic algorithm (RCGA). Int. J. Mech. Sci. 217, 107030 (2022).

Acknowledgement

Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) - 532148125 and supported by the central publication fund of Hochschule Düsseldorf University of Applied Sciences.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K.M. Software, Validation, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft; N.B. Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; N.K.M. Investigation, Visualization; D.K.G. Data Curation, A.C.B. Reviewing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mandal, D.K., Biswas, N., Manna, N.K. et al. An application of artificial neural network (ANN) for comparative performance assessment of solar chimney (SC) plant for green energy production. Sci Rep 14, 979 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46505-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46505-1

This article is cited by

-

Integrated use of finite element analysis and gaussian process regression in the structural analysis of AISI 316 stainless steel chimney systems

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The impact of different protruding absorber surface configurations on the efficiency of solar chimney power plant

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2025)