Abstract

Alcohol consumption in Tanzania exceeds the global average. While sociodemographic difference in alcohol consumption in Tanzania have been studied, the relationship between psycho-cognitive phenomena and alcohol consumption has garnered little attention. Our study examines how depressive symptoms and cognitive performance affect alcohol consumption, considering sociodemographic variations. We interviewed 2299 Tanzanian adults, with an average age of 53 years, to assess their alcohol consumption, depressive symptoms, cognitive performance, and sociodemographic characteristics using a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. The logistic portion of our model revealed that the likelihood alcohol consumption increased by 8.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.6%, 13.1%, p < 0.001) as depressive symptom severity increased. Conversely, the count portion of the model indicated that with each one-unit increase in the severity of depressive symptoms, the estimated number of drinks decreased by 2.3% (95% CI [0.4%, 4.0%], p = .016). Additionally, the number of drinks consumed decreased by 4.7% (95% CI [1.2%, 8.1%], p = .010) for each increased cognitive score. Men exhibited higher alcohol consumption than women, and Christians tended to consume more than Muslims. These findings suggest that middle-aged and elderly adults in Tanzania tend to consume alcohol when they feel depressed but moderate their drinking habits by leveraging their cognitive abilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol consumption has raised major public health and socio-economic concerns worldwide. In Tanzania, 30% of patients seeking acute injury care tested positive for alcohol use1, with problematic drinking associated with a six-fold increase in the odds of injury2. Moreover, there is a dose-dependent relationship between the amount of alcohol intake and the odds of injury1. Apart from the health risks associated with problematic alcohol use3, its broader societal impacts extend to healthcare costs, the risk of infectious diseases, crime and antisocial behaviours4.

Moreover, alcohol use among middle-aged and older adults is increasingly common and has been trending upward over the years5,6. A national epidemiologic survey on alcohol in the United States showed substantial increases in alcohol use (22%), high-risk drinking (65%), and alcohol use disorder (107%) among older adults between 2001 and 20137. Such a longitudinal survey in Sub-Saharan Africa – currently lacking – is highly desirable. Unlike younger adults, middle-aged and older adults are at greater risk to problematic alcohol use due to age-associated psychophysical and neurophysiological degenerations6,8. However, alcohol-related problems in middle-aged and older adults often remain hidden. The signs of problematic alcohol use can mimic geriatric syndromes and be masked by comorbid physical or psychiatric illness, making detection challenging9. Meanwhile, the global population is rapidly ageing. By 2050, the World Health Organization estimates that there will be 2 billion people aged over 60 (22% of the world population), with 80% of older people living in low- and middle-income countries (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health). Rising rates of alcohol use among middle-aged and older adults, combined with alcohol-related multimorbidity, may bring new challenges to already burdened healthcare systems10. There is a lack of knowledge about alcohol use among middle-aged and older adults in low- and middle-income countries11.

In addition, cultural, socioeconomic, and environmental contexts can profoundly shape alcohol consumption patterns and subsequent healthcare outcomes12,13,14. These factors span a broad range, including religious beliefs, gender norms, economic conditions, the impact of the pandemic, and healthcare policies and financing15,16,17,18,19,20,21. For instance, in Islamic cultures, where alcohol consumption is restricted, intake rates are generally lower, resulting in fewer alcohol-related health issues15,16. Similarly, in certain contexts, societal norms discourage women from drinking, further affecting alcohol intake17. Other factors such as poverty, unemployment, and income status can contribute to variations in alcohol consumption patterns18,19. Furthermore, the pandemic22 can introduce new dynamics, affecting alcohol consumption through changes in availability, accessibility, and social restrictions20,23. To address alcohol-related health behaviours and outcomes, it is essential to implement effective detection and diagnosis techniques24, improve healthcare financing and regulation21,25,26,27, as well as enhance health education and awareness28,29. By examining context-specific factors, insights can be gained to develop tailored interventions and healthcare strategies to address alcohol-related health issues effectively.

Given the substantial burden of alcohol-related problems, research on alcohol remains critically lacking in Tanzania. Previous studies in Tanzania have primarily focused on the sociodemographic factors associated with alcohol consumption30,31,32,33. For instance, heavy alcohol use is more prevalent among men and non-Muslims than women and Muslim30,31. However, there remains a gap in understanding the psychological processes that underlie problematic drinking, particularly the role of cognitive performance in regulating the negative emotions that drive alcohol consumption34,35. It is well known that people often drink alcohol to cope with negative emotions36. They may consume alcohol to alleviate unpleasant emotional states, benefiting from its acute anxiolytic effects37,38. However, over time, this maladaptive behaviour become less responsive to cognitive ability, reinforcing the relationship between negative emotions and compulsive alcohol use39. Cognitive performance can regulate this motivational process to keep drinking in check40. As such, the balance between negative emotions and cognitive performance may significantly determine drinking behaviour40. Despite its importance, the relationship between psycho-cognitive phenomena and alcohol consumption has garnered little attention in Tanzania to date.

One challenge in modelling alcohol consumption outcomes is appropriately accounting for the distribution of drinking patterns. These distributions often have a high frequency of zeros, representing non-drinkers and abstinent individuals, and a long right tail, representing heavy drinkers41. A common strategy is to reduce the information in the data to a dichotomous outcome (comparing zero versus non-zero) or to use log transformations42. However, zeros cannot be log-transformed, and other approaches, such as adding “1” to the count outcomes with an excess of zeros before log transformation, do not adequately solve the problem. When dealing with datasets featuring a considerable number of zero counts and overdispersion, it is essential to employ statistical methods capable of accommodating this phenomenon. In this study, we propose employing a statistical approach to uncover patterns of alcohol consumption exhibiting significant variability across multiple conditions (e.g., age gender, education level, and religion). Specifically, we advocate for the adoption of a zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) regression model43 for data analysis. This model effectively addresses the challenge posed by excess zeros and overdispersion frequently encountered in datasets with a large number of zero-count observations, such as when modelling the number of alcohol drinks consumed per week in the general population. In such cases, where the variance exceeds the mean, the assumption of the Poisson distribution is violated44,45. The ZINB distribution, a mixture model combining a negative binomial distribution (represented by a count component) and a logit distribution (represented by a zero component), is instrumental in this regard. The dependent variable can take nonnegative integer values, including 0, 1, 2, 3, and beyond. ZINB regression, therefore, can effectively capture the intricate distribution of the data and furnish a comprehensive understanding of the variables influencing alcohol consumption, even amidst datasets marked by intricate zero-counts patterns.

In our study, we aim to explore the relationship between psycho-cognitive phenomena and alcohol consumption among middle-aged and older adults in Tanzania, considering sociodemographic characteristics. We hypothesize that greater severity of depressive symptoms and lower cognitive performance will be associated with both an increased likelihood of alcohol consumption and a higher number of alcohol drinks. Furthermore, we expect that these effects will vary across different sociodemographic factors, such as education, gender, and religion.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study was conducted between June 2017 and July 2018 in Tanzania, using home interviews as part of the “Health and Ageing in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community (HAALSI)” project among older adults in Dar es Salaam46,47. The HAALSI sample was embedded within the Dar es Salaam Urban Cohort Study (DUCS), which operated as a health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS)48. Participants were recruited from residents and households in the Ukonga and Gongo la Mboto wards of Ilala district in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Field workers conducted in-person interviews at each participant’s home. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Office of Human Research Administration (ref. C13–1608–02) and the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences. All procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and the ethical standards of the responsible ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Measurements

The interview included assessments of sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, gender, education level, and religion, as well as evaluations of alcohol consumption, depressive symptoms, and cognitive performance. To evaluate alcohol consumption, we employed the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ)49. Participants were asked about the frequency of their alcohol consumption (i.e., number of drinking days per week) and the quantity consumed (i.e., number of standard drinks consumed on drinking days per week) over the past month. Show-cards for standard drinks and a table of equivalent alcohol units per drink (beer, wine, liquor, and spirits) were provided as reference. Total alcohol consumption was calculated by multiplying the quantity by the frequency.

To measure the severity of depressive symptoms, we employed the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10)50. Each item had a Likert scale ranging from 0 (“rarely or none of the time”) to 3 (“all of the time”). Higher scores indicated greater severity of depressive symptoms. To estimate reliability, we calculated the Cronbach’s alpha value within our sample51.

To assess cognitive function, we employed the Oxford Cognize Screen (OCS-Plus)52. This tool prioritizes visual-oriented tasks, thus minimizing language requirements and cultural biases. It has been validated in low-literacy and socioeconomic settings, as well as among individuals characterized by healthy aging53. To assess reliability within our sample, we computed the Cronbach’s alpha value. We administered an adapted version of the HAALSI survey in South Africa54, which included tasks for immediate and delayed recall, counting, numeracy, and orientation55. The overall score ranged from 0 to 26 points, with higher scores indicating better cognitive performance. In the immediate and delayed recall tasks, participants were asked to memorize a list of 10 words and then recall as many words as possible immediately and again after a timed delay interval (1 point for each correctly recalled word, totalling 20 points for both immediate and delayed recall). In the numeracy task, participants were required to complete the numeric sequence starting with two, four, and six (1 point). In the counting task, participants were asked to count sequentially from one to twenty (1 point). In the orientation task, participants were asked to answer the current year, month, date, and president of Tanzania (1 point for each correct answer, totalling 4 points).

Data analysis

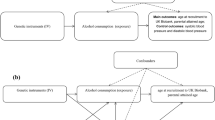

We conducted statistical analyses using R version 4.1.0. (www.r-project.org). To handle observations with missing data in all variables, we opted not to remove them, as this could introduce bias into the model. Instead, we used random forest imputation to develop an unbiased estimate for missing values56. Specifically, we employed the ‘missForest’ function in R package57, which uses a random forest trained on observed values of a data matrix to predict the missing values. For variables with excessive zeros (i.e., individuals reporting zero drinks per week), we built a ZINB regression model43. This model simultaneously estimates logistic and count portions. We used the alcohol consumption (i.e., standard drinks per week) as the dependent variable, while CES-D-10 depression symptom scores and cognitive performance scores were treated as independent variables, controlling for gender (men versus women; coding: 0 versus 1), age (continuous variable), education level (catalogue variable), and religion (Christians versus Muslims; coding: 0 versus 1) in our analyses. The logistic portion reports odds ratios (OR) of excess zeros (i.e., the likelihood of reporting zero drinks), while the count portion describes incident risk ratios (IRR) for the number of drinks consumed. Due to the logistic link functions used in the model‐fitting procedure, we exponentiated coefficients in the model output to report the ORs for drinking alcohol compared to not drinking alcohol and IRRs for the number of drinks consumed. Differences were considered as statistically significant at p < 0.05 and highly statistically significant at p < 0.01.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

A total of 2299 adults (1429 women; age range: 32–103, Median = 50, Mean = 52.92, SD = 10.68) were interviewed at home in Tanzania. The sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. On average, participants reported consuming 2.51 standard drinks per week (SD = 8.53). Among all seven variables of interest (i.e., age, gender, educational level, religion, CES-D-10 depression symptom score, and cognitive score), 6.12% of missing values (985 out of 16,093) were imputed using random forest.

In our study, the measurement scales demonstrated acceptable reliability within our sample, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha values51. The Swahili version of the CES-D-10 exhibited strong reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.84. Furthermore, the OCS-Plus displayed consistent reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.62. A Cronbach’s alpha value ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 is considered acceptable58.

Association between independent correlates and alcohol consumption

On one hand, the logistic portion of our zero‐inflated negative binomial model analysis revealed that participants exhibiting depressive symptoms were estimated to be 8.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.6%, 13.1%, p < 0.001) less likely to report zero drinks, indicating an increased likelihood of alcohol consumption as depressive symptom severity increased, shown in Table 2. However, cognitive performance scores showed no significant relationship with alcohol intake (p = 0.868).

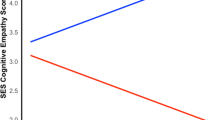

On the other hand, in the count portion of the model, each additional point in depressive symptom severity was associated with a decrease of 2.3% (95% CI [0.4%, 4.0%], p = 0.016) in the estimated number of drinks per week. Conversely, for each increase in cognitive performance score, there was a decrease of 4.7% (95% CI [8.1%, 1.2%], p = 0.010) in the estimated number of drinks per week, shown in Table 2. These results suggest that while middle-aged and older adults are more likely to drink alcohol when experiencing depressive symptoms, they do not drink excessively by leveraging their cognitive abilities.

In addition, in both logistic and count portions of the model, we found that higher educational levels, male gender, and Christian religion were associated with higher alcohol consumption. Specifically, individuals with higher education levels were more likely to consume alcohol compared to those with lower education levels. Moreover, men were more likely to have higher alcohol consumption compared to women, and Christians were more likely to consume alcohol compared to Muslims (all Ps < 0.05).

Discussion

We investigated the relationship between psycho-cognitive phenomena and alcohol consumption in Tanzania considering sociodemographic factors. Consistent with our hypothesis built upon previous studies conducted outside Tanzania59, we discovered that middle-aged and older adults in Tanzania tend to consume alcohol when they feel depressed. Surprisingly, we found that they exhibit moderation in alcohol intake, with increased severity of depressive symptoms and higher cognitive performance associated with lower numbers of alcohol drinks. Moreover, our findings revealed associations between alcohol use and sociodemographic factors, as expected. Specifically, individuals with higher education levels were found to consume more alcohol compared to those with lower education levels. Men exhibited higher alcohol consumption than women, and Christians consumed more alcohol than Muslims.

Our study highlights the relationship between psycho-cognitive status and alcohol‐drinking patterns among middle-aged and older adults in Tanzania. We discovered that while these individuals are more likely to consume alcohol when experiencing depressive symptoms, they do not tend to engage in excessive drinking as the severity of these symptoms increases. This unexpected evidence of moderation in alcohol intakes sheds light on the complex interplay between mental health and alcohol use. It facilitates further consideration of the potential mediation of alcohol consumption in the association between common mental disorders and cardiovascular disease as well as all-cause mortality60,61. Moreover, our study contributes to the advancement of mental health and alcohol research in the region, offering valuable insights to inform strategies aimed at preventing problematic alcohol use. On one hand, our findings highlight the importance of perceived social support in mitigating alcohol use as a coping mechanism for depression62,63. On the other hand, structural interventions are needed to address problematical alcohol use in Tanzania64,65. For instance, previous research conducted in Tanzania has demonstrated the association between alcohol advertising and drinking behaviour65, prompting the implementation of health warning labels on all alcohol advertisements as a preventive measure64. These efforts reflect the ongoing commitment to combating alcohol-related issues and promoting public health in Tanzania.

Contrary to our hypothesis, cognitive performance did not appear to be a significant determinant of whether middle-aged and older adults chose to drink or not. However, consistent with our expectations, we found that higher cognitive performance was associated with a lower number of drinks consumed. Thes mixed results indicate that while cognitive performance may not directly drive the decision to drink, it does play a role in regulating excessive alcohol consumption, particularly in relation to problematic alcohol use. Our results align with findings from a cross-sectional study by Humphreys and co-workers54, which found that higher cognitive performance was associated with lower alcohol use among older adults in South Africa. Conversely, another direction of the relationship has been identified: older adults in India who consumed alcohol had a 30% higher likelihood of experiencing cognitive impairment66. Future studies should further investigate the directionality and causality of these relationships.

Our study suggested that middle-aged and older adults in Tanzania do not drink excessively when they feel depressed, possibly by leveraging their cognitive abilities. This implies that individuals who maintain cognitive function may indeed refrain from engaging in problematic alcohol use. Psychoeducation, cognitive reappraisal, skills training, and other behavioural strategies could potentially aid in enhancing cognitive ability and consequently reducing the likelihood of problematic alcohol consumption. It is worth noting that our sample predominantly comprised middle‐and older‐age adults, deliberately lacking representation from younger individuals, as our research is cantered on studying aging populations. A cross-sectional and longitudinal study conducted among a large Dutch student sample did not find a significant association between cognitive performance and alcohol consumption67. Given that the peak age range for problematic alcohol consumption in Tanzania falls between 25 and 34 years33, there is a clear need for further research including a broad age range, as age may have an impact on cognitive performance. In addition, future studies could include other types of cognitive instruments to assess cognitive control (e.g., response inhibition) and decision-making processes (i.e., risk taking) in alcohol intake68. This approach could provide deeper insights into the intricate relationship between cognitive functioning and alcohol consumption across different age groups.

Furthermore, our study added to the existing evidence indicating that men tend to consume more alcohol than women, and Christians exhibit higher alcohol consumption compared to Muslims in Tanzania30,32,33. However, the association of alcohol use with a range of sociodemographic factors warrants further research.

The study has several limitations that warrant emphasis. First, while our findings provide valuable insights into associations, they cannot establish causality. To determines causal inferences, longitudinal observational studies are needed. Second, our participants were recruited solely from Dar es Salaam, which introduces geographical bias and limits the generalizability of our results to other parts of Tanzania or East Africa. Future studies should consider cross-country comparisons69,70,71, especially within Africa, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of alcohol consumption among middle-aged and older adults. Third, our current study did not assess drinking motives, perceptions of alcohol use72, or the underlying causes of depressive symptoms. Incorporating these aspects into more detailed qualitative studies would generate a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between psycho-cognitive phenomena and alcohol consumption in Tanzania.

Our research holds valuable implications for both the healthcare system and managerial practices. Understanding the relationship between depressive symptoms, cognitive performance and alcohol consumption among middle-aged and older adults in Tanzania can provide valuable insights for healthcare providers, informing the need for tailored interventions and support services. For the healthcare system, our findings may catalyse the development of tools to identify and safeguard individuals at risk of problematic alcohol use, particularly those experiencing depressive symptoms, male gender, and adhering to Christian beliefs. Furthermore, our study may illuminate healthcare financing by employing financial econometrics73 to account for mental health costs and services, as well as the social and economic costs associated with alcohol-related health outcomes74,75,76. In addition, incorporating high-tech health infrastructure into healthcare planning77 and leveraging digital tools78 can enhance health service accessibility, scalability, and sustainability, ensuring comprehensive health coverage. These proactive approaches can facilitate cost-effective prevention and early intervention, thereby alleviating the burden on healthcare resources associated with alcohol-related issues21. From a managerial standpoint, our research highlights the importance of considering cognitive awareness and health education in addressing alcohol-related challenges29. This insight could be integrated into training programs, media advocacy, alcohol control policies, and community outreach initiatives aimed at promoting responsible alcohol consumption79. Overall, our research has the potential to inform strategic decisions and interventions within both healthcare and managerial contexts, ultimately contributing to improved public health outcomes and enhanced quality of life for individuals.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that middle-aged and older adults in Tanzania are inclined to consume alcohol when experiencing depressive symptoms, yet they moderate their drinking behaviour by leveraging cognitive abilities. Building upon our findings, future research could explore various avenues to enrich our understanding and inform targeted interventions. This includes conducting comparative and spatial–temporal analyses73,77,80,81 across diverse regions to uncover variations in alcohol consumption behaviours, thereby guiding context-specific interventions. Moreover, further investigation into the underlying psycho-cognitive mechanisms driving alcohol consumption behaviours can inform the design of targeted interventions and policies79. Additionally, future studies can focus on exploring associated healthcare costs, burden on healthcare resources, and potential interventions to mitigate negative health outcomes related to alcohol consumption in specific contexts21. By pursuing these avenues of research, we can advance our knowledge of alcohol consumption behaviours and inform comprehensive psycho-cognitive strategies to address alcohol-related challenges and improve public health in Tanzania and beyond.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Staton, C. A. et al. The impact of alcohol among injury patients in Moshi, Tanzania: a nested case-crossover study. BMC Public Health 18, 1–9 (2018).

Kiwango, G. et al. Association between alcohol consumption, marijuana use and road traffic injuries among commercial motorcycle riders: a population-based, case-control study in Dares Salaam, Tanzania. Accident Anal. Prevent. 160, 106325 (2021).

Leong, C. et al. Association of alcohol use disorder on alcohol-related cancers, diabetes, ischemic heart disease and death: a population-based, matched cohort study. Addiction 117, 368–381 (2022).

Kirby J, Van der Sluijs W and Inchley J. Young people and substance use: The influence of personal, social and environmental factors on substance use among adolescents in Scotland. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland 2008.

Breslow, R. A. et al. Trends in alcohol consumption among older Americans: national health interview surveys, 1997 to 2014. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 41, 976–986 (2017).

Falk Erhag, H. et al. Alcohol use and drinking patterns in Swedish 85 year olds born three decades apart–findings from the Gothenburg H70 study. Age Ageing 52, afad041 (2023).

Grant, B. F. et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. JAMA Psychiat. 74, 911–923 (2017).

Kuhns, L. et al. Age-related differences in the effect of chronic alcohol on cognition and the brain: a systematic review. Transl. Psych. 12, 345 (2022).

O’Connell, H. et al. Alcohol use disorders in elderly people–redefining an age old problem in old age. BMJ 327, 664–667 (2003).

Kuerbis, A. & Sacco, P. A review of existing treatments for substance abuse among the elderly and recommendations for future directions. Substance Abuse: Res. Treat. 7, 7865 (2013).

Megherbi-Moulay O, Igier V, Julian B, et al. Alcohol use in older adults: A systematic review of biopsychosocial factors, screening tools, and treatment options. Int. Jo. Mental Health Addict. 2022: 1–43.

Sudhinaraset, M., Wigglesworth, C. & Takeuchi, D. T. Social and cultural contexts of alcohol use: influences in a social–ecological framework. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 38, 35 (2016).

Khamis, A. A. et al. Alcohol consumption patterns: a systematic review of demographic and sociocultural influencing factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 8103 (2022).

Stevely, A. K., Holmes, J. & Meier, P. S. Contextual characteristics of adults’ drinking occasions and their association with levels of alcohol consumption and acute alcohol-related harm: a mapping review. Addiction 115, 218–229 (2020).

Najjar, L. Z. et al. Religious perceptions of alcohol consumption and drinking behaviours among religious and non-religious groups. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 19, 1028–1041 (2016).

Michalak, L. & Trocki, K. Alcohol and Islam: an overview. Contemp. Drug Probl. 33, 523–562 (2006).

Lyons, A. C. & Willott, S. A. Alcohol consumption, gender identities and women’s changing social positions. Sex Roles 59, 694–712 (2008).

Mossakowski, K. N. Is the duration of poverty and unemployment a risk factor for heavy drinking?. Soc. Sci. Med. 67, 947–955 (2008).

Keyes, K. M. & Hasin, D. S. Socio-economic status and problem alcohol use: the positive relationship between income and the DSM-IV alcohol abuse diagnosis. Addiction 103, 1120–1130 (2008).

Sohi, I. et al. Changes in alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic and previous pandemics: a systematic review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 46, 498–513 (2022).

Anderson, P., Chisholm, D. & Fuhr, D. C. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 373, 2234–2246 (2009).

Okafor, S. et al. COVID-19 public health and social measures in Southeast Nigeria and its implication to public health management and sustainability. Oppor. Chall. Sustain. 1, 61–75 (2022).

Haucke, M., Heinzel, S. & Liu, S. Involuntary social isolation and alcohol consumption: an ecological momentary assessment in Germany amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Alcohol Alcohol. 59(1), adad069 (2024).

Baig, M. et al. Pneumonia detection technique empowered with transfer learning approach. Healthcraft Front. 2, 20–33 (2024).

Jafar, A. & Quadri, U. Macroeconomic outcomes of healthcare financing reforms in Nigeria: a computable general equilibrium analysis. J. Account., Finance Audit. Studies 9, 420–448 (2023).

Roberts, M. J. et al. Getting health reform right: A guide to improving performance and equity (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Yip, W. et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in universal health coverage. The Lancet 394, 1192–1204 (2019).

Reca, R. et al. Impact of maternal health education on pediatric oral health in Banda Aceh: a quasi-experimental study. Healthcraft Frontiers 2, 10–19 (2024).

Manthey, J. et al. Improving alcohol health literacy and reducing alcohol consumption: recommendations for Germany. Addict. Sci. Clin. Practice 18, 28 (2023).

Francis, J. M. et al. The epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders among young people in Northern Tanzania. PLOS ONE 10, e0140041 (2015).

Green, M. Trading on inequality: gender and the drinks trade in southern Tanzania. Africa 69, 404–425 (1999).

Mitsunaga, T. & Larsen, U. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with alcohol abuse in Moshi, northern Tanzania. J. Biosoc. Sci. 40, 379–399 (2008).

Mbatia, J., Jenkins, R., Singleton, N. & White, B. Prevalence of alcohol consumption and hazardous drinking, tobacco and drug use in urban Tanzania, and their associated risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 6(7), 1991–2006 (2009).

Cooper, M. L. et al. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 69, 990 (1995).

Cox, W. M. & Klinger, E. A motivational model of alcohol use: Determinants of use and change. J. Abnormal Psychol. 97, 168–180 (1988).

Holahan, C. J. et al. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: a ten-year model. J. Studies Alcohol 62, 190–198 (2001).

Collins, J.-L. et al. Drinking to cope with depression mediates the relationship between social avoidance and alcohol problems: A 3-wave, 18-month longitudinal study. Addict. Behav. 76, 182–187 (2018).

Clay, J. M. & Parker, M. O. Alcohol use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: A potential public health crisis?. Lancet Public Health 5, e259 (2020).

Robins, M. T., Heinricher, M. M. & Ryabinin, A. E. From pleasure to pain, and back again: the intricate relationship between alcohol and nociception. Alcohol Alcohol. 54, 625–638 (2019).

Le, T. M. et al. Problem drinking and the interaction of reward, negative emotion, and cognitive control circuits during cue-elicited craving. Addict. Neurosci. 1, 100004 (2022).

Horton, N. J., Kim, E. & Saitz, R. A cautionary note regarding count models of alcohol consumption in randomized controlled trials. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 7, 1–9 (2007).

Green, J. A. Too many zeros and/or highly skewed? A tutorial on modelling health behaviour as count data with Poisson and negative binomial regression. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 9, 436–455 (2021).

Atkins, D. C. & Gallop, R. J. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: a tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. J. Family Psychol. 21, 726 (2007).

Saputro DRS, Susanti A and Pratiwi NBI. The handling of overdispersion on Poisson regression model with the generalized Poisson regression model. In: AIP Conference Proceedings 2021, AIP Publishing.

Warton, D. I. Many zeros does not mean zero inflation: Comparing the goodness-of-fit of parametric models to multivariate abundance data. Environ. Offic. J. Int. Environ. Soc. 16, 275–289 (2005).

Christopher, E. et al. Disclosure of intimate partner violence by men and women in Dar es Salaam Tanzania. Front. Public Health 10, 928469 (2022).

Kim, H. Y. et al. High prevalence of self-reported sexually transmitted infections among older adults in Tanzania: results from a list experiment in a population-representative survey. Ann. Epidemiol. 1(84), 48–53 (2023).

Leyna, G. H. et al. Profile: the Dar Es Salaam health and demographic surveillance system (Dar es Salaam HDSS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 801–808 (2017).

Collins, R. L., Parks, G. A. & Marlatt, G. A. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 53, 189 (1985).

Baron, E. C., Davies, T. & Lund, C. Validation of the 10-item centre for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D-10) in Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans populations in South Africa. BMC Psych. 17, 1–14 (2017).

Kline P. Handbook of psychological testing. Routledge, 2013.

Demeyere, N. et al. The oxford cognitive screen (OCS): validation of a stroke-specific short cognitive screening tool. Psychol. Assessment 27, 883 (2015).

Demeyere, N. et al. Introducing the tablet-based oxford cognitive screen-plus (OCS-Plus) as an assessment tool for subtle cognitive impairments. Sci. Rep. 11, 8000 (2021).

Humphreys, G. W. et al. Cognitive function in low-income and low-literacy settings: validation of the tablet-based oxford cognitive screen in the health and aging in Africa: a longitudinal study of an INDEPTH community in South Africa (HAALSI). J. Gerontol.: Series B 72, 38–50 (2017).

Gómez-Olivé, F. X. et al. Cohort profile: health and ageing in Africa: a longitudinal study of an INDEPTH community in South Africa (HAALSI). Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 689–690j (2018).

Stekhoven, D. J. & Bühlmann, P. MissForest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 28, 112–118 (2012).

Stekhoven DJ. missForest: Nonparametric Missing Value Imputation using Random Forest. R package version 15 2022.

Taber, K. S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Education 48, 1273–1296 (2018).

Ning, K. et al. The association between early life mental health and alcohol use behaviours in adulthood: a systematic review. PloS ONE 15, e0228667 (2020).

Bell, S. & Britton, A. An exploration of the dynamic longitudinal relationship between mental health and alcohol consumption: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 12, 1–13 (2014).

Degerud, E. et al. Association of coincident self-reported mental health problems and alcohol intake with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: a Norwegian pooled population analysis. PLOS Medicine 17, e1003030 (2020).

Mboya, I. B. et al. Factors associated with mental distress among undergraduate students in northern Tanzania. BMC Psych. 20, 1–7 (2020).

Mavandadi, S. et al. The moderating role of perceived social support on alcohol treatment outcomes. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs 76, 818–822 (2015).

Morojele, N. K. et al. Alcohol consumption, harms and policy developments in sub-Saharan Africa: The case for stronger national and regional responses. Drug Alcohol Rev. 40, 402–419 (2021).

Ibitoye, M. et al. The influence of alcohol outlet density and advertising on youth drinking in urban Tanzania. Health Place 58, 102141 (2019).

Muhammad, T., Govindu, M. & Srivastava, S. Relationship between chewing tobacco, smoking, consuming alcohol and cognitive impairment among older adults in India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics 21, 1–14 (2021).

Hendriks, H. et al. Alcohol consumption, drinking patterns, and cognitive performance in young adults: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Nutrients 12, 200 (2020).

Zech, H. et al. Measuring self-regulation in everyday life: reliability and validity of smartphone-based experiments in alcohol use disorder. Behav. Res. Methods 55(8), 4329–4342 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. High mind wandering correlates with high risk for problematic alcohol use in China and Germany. Eur. Arch. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 274, 335–341 (2024).

Lau A, Li R, Huang C, et al. Self-esteem mediates the effects of loneliness on problematic alcohol use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2023: 1–13.

Clausen, T. et al. Diverse alcohol drinking patterns in 20 African countries. Addiction 104, 1147–1154 (2009).

Pauley A, Metcalf M, Buono M, et al. Understanding the impacts and perceptions of alcohol use in Northern Tanzania: A mixed-methods analysis. medRxiv 2023: 2023.2009. 2011.23295395.

Darie, F. & Tache, I. Volatility of the Dow Jones pharmaceuticals and biotechnology index in the context of the Coronavirus crisis. J. Corporate Governance, Insurance, Risk Manag. 7, 42–54 (2020).

De Goeij, M. C. et al. How economic crises affect alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health problems: a realist systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 131, 131–146 (2015).

Thavorncharoensap, M. et al. The economic impact of alcohol consumption: a systematic review. Substance Abuse Treat. Prevent. Policy 4, 1–11 (2009).

Hummel, D. The potential effects of the social costs from alcohol consumption on state financial condition. J. Public Budget. Account. Financ. Manag. 30, 53–68 (2018).

Naranjo, J. Evaluating spatial accessibility to high-tech health services in the Spanish Iberian Peninsula: a GIS-based analysis. Opportunities Chall. Sustain. 3, 62–71 (2024).

Liu, S., Heinzel, S. & Dolan, R. J. Digital phenotyping and mobile sensing in addiction psychiatry. Pharmacopsychiatry 54, 287–288 (2021).

Giesbrecht, N., Bosma, L. M. & Reisdorfer, E. Reducing harm through evidence-based alcohol policies: challenges and options. World Med. Health Policy 11, 248–269 (2019).

Emumejakpor, S. & Adewumi, A. Comparative analysis of heavy metal concentrations and potential health risks across varied land-use zones in Ado-Ekiti Southwest Nigeria. Acadlore Transact. Geosci. 2, 113–131 (2023).

Liu, J., Tian, B. & Wu, J. Temporal analysis of infectious diseases: A case study on COVID-19. Acadlore Transact. Appl. Math. Stat. 1, 1–9 (2023).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study is funded by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AG024409.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WF, MMS, JK, and TB conceptualized the study. JKR, JK, JMF, and TB designed the study. PK, GHL, JMF participated in the acquisition of data. SL and TB analysed data. SL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SS, AIA, CP, DS, and TB reviewed and edited the drafts. All authors reviewed and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Kazonda, P., Leyna, G.H. et al. Emotional and cognitive influences on alcohol consumption in middle-aged and elderly Tanzanians: a population-based study. Sci Rep 14, 17520 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64694-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64694-1