Abstract

The initiation of the program Mental Health Support Program for Coronavirus Infection addressed the increased demand for mental health services in the province of Salamanca, resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The psychiatry service provided care for COVID-19 patients, their families, and healthcare workers who treated them, as these groups were identified as being at risk. This study aims to describe the assistance provided, including personnel and resources utilized, types of interventions carried out, and to assess the demand for mental health care and predominant symptoms and emotions experienced by patients. Billboards and the complex’s intranet publicized the program. Specific clinical approach using telemedicine were provide from March 2020 to December 2021 to COVID-19 patients, their relatives, and healthcare workers. 216 patients were included with a mean age of 53.2 years, with women comprising 77.3% of this group. All the groups received treatment in similar proportions. Over a period of 730 h, a total of 1376 interventions were performed, with an average duration of 31.8 min per intervention. The program could treat 79.6% of these patients without requiring referrals to other services. When the program concluded, only 21 participants (9.7%) were discharged to the local mental health network to continue their mental health treatment. The program effectively reduced the burden on regular mental health services due to its ability to treat most patients without requiring referrals. The program was able to attend to most mental health requests with minimal involvement of the regular mental health service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In December 2019, Spain issued a COVID-19 alert. During this time, transportation was restricted, a lockdown was implemented, and only essential economic activities were permitted1. In 2020, COVID-19 accounted for 28.3% of total deaths, with 60,358 registered deaths. In Castilla y León region, the Odds Ratio (OR) of dying from COVID-19 compared to any other cause was 2.97 (95% CI 2.87–3.08)2.

Prolonged exposure to traumatic events and stressors can significantly impact psychological health. Previous studies on COVID-19 epidemic alert have shown that these events can affect the mental health of populations and may result in conditions such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, or depression3,4. In Spain, cases of depression, anxiety, and PTSD increased during COVID-19 alert5. These conditions disproportionately affected women who had family members infected with COVID-19 or who had a previous diagnosis of mental illness6. Additionally, there was widespread fear of contracting the disease and uncertainty about the future as the number of infections and deaths continued to rise.

Among patients with COVID-19, evidence shows a prevalence of 45% for depression (95% CI 37–54%), 47% for anxiety (95% CI 37–57%), and 34% for insomnia (95% CI 19–50%)7. Healthcare workers8 and patients themselves9 are among the most vulnerable groups. Compared to pre-pandemic levels, healthcare workers have reported increased anxiety (OR 3.03; 95% CI 2.53–3.62), increased substance use (OR 5.74; 95% CI 2.53–13.03), and greater burnout from patient care (OR 5.19; 95% CI 3.61–7.46)8. Insomnia, anxiety, and depression have been common symptoms among healthcare workers10, with some individuals even experiencing suicidal thoughts11 rising suicide rates and increased utilization of mental health services12. Furthermore, a relationship between mental health and increased mortality among COVID-19 patients has been established9.

The pandemic has also impacted the relatives of individuals affected by COVID-1913. Living with someone infected with COVID-19 has been identified as a risk factor for mental health problems, indicating that the pandemic has had consequences for both the physical and mental health of family members or those who care for them11,12. The pandemic has necessitated the reorganization of healthcare services, with consequences for the well-being of healthcare professionals10,14. Alongside the COVID-19 pandemic, there has also been a surge in psychiatric illness15.

It has been claimed that early psychological intervention and treatment can help mitigate the effects of PTSD, anxiety, depression, and other chronic psychological conditions among various population groups11. Due to limitations on in-person contact resulting from the risk of contagion, telemedicine has been successfully implemented and has proven effective in addressing mental health needs during the COVID-19 pandemic16. As a result, specific mental health programs targeting vulnerable populations are needed, trying to avoid overbooking of the regular mental health service17,18.

To address the increased demand for mental health services, Salamanca initiated the Mental Health Support Program for Coronavirus Infection called PASMICOR. This study aims to evaluate the PASMICOR program as a whole, from its inception to its conclusion. A previous manuscript was published with data from the first 9 months because we deemed it highly important to inform other hospitals about the specific program being implemented, so they could replicate it. However, this current article encompasses the program in its entirety: from inception to conclusion, emphasizing the effectiveness of the complete program. The general objectives of this study are to describe the mental health care response provided to COVID-19 patients, their family members, and healthcare professionals over the 18-month duration of the program; to assess whether the program was able to meet demand during a national emergency without requiring referrals; to evaluate the number of psychology professionals and proportion of users per population in the province of Salamanca; and to assess patient outcomes and overall program effectiveness. The specific objectives are to identify the most common symptoms and emotions experienced by patients; to determine the types of interventions used; to assess the personnel and time required to meet demand; and to evaluate the effectiveness of telepsychology as a practical form of assistance.

Methods

The initiation of the PASMICOR program occurred during a peak in hospitalizations in March 2020 and concluded at the end of December 2021. The PASMICOR program was established with the primary purpose of preventing adverse mental health outcomes that could arise from the pandemic, confinement, and social alarm. By providing care for individuals who might otherwise overwhelm mental health services, the program was strategically designed to alleviate the strain on mental health network.

To be eligible for the PASMICOR program, individuals had to meet certain criteria. They had to be either a COVID-19 patient, a family member of a COVID-19 patient, or a healthcare professional caring for COVID-19 patients. Additionally, they could not be currently receiving treatment for a mental disorder from another healthcare professional, both to avoid interfering with their ongoing treatment and to align with the program's objectives of addressing the needs of individuals underserved regarding COVID-19-related issues. Furthermore, they could not have an acute illness, and had to have the ability to communicate with medical personnel via speaking Age was not a criteria selection. Eligible individuals also had to provide their express consent to participate in the program. Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants and/or their legal guardians. Individuals residing outside the province of Salamanca were excluded from participation.

Advertising posters were displayed in common areas of the University of Salamanca Health Care Complex and the University of Salamanca Healthcare Complex intranet disseminated information about the program. Primary Care Management and professional associations for nursing homes also promoted the program.

The professional attending to COVID-19 patients offered specialized mental health care services to both the COVID-19 patients and their families, provided they met the inclusion criteria. If they accepted the treatment, a request was generated via email. Health professionals could also access this service, provided they sent an internal email with the request themselves. These requests were received by a clinical psychologist who conducted a personalized evaluation process to classify, and triage based on factors such as symptom severity and type of user (e.g., COVID-19 patient, family member, or healthcare worker). This information was used to assign each patient to an appropriate mental health professional who could best address their needs. Once assigned, patients received telephone-based interventions from their assigned psychologist.

A standardized document was used to record each patient’s coded identification information while anonymizing their personal data (see supplementary material). This registry also included information on sociodemographic variables (e.g., sex, age, marital status, profession, employment status), group membership (e.g., COVID-19 patient, healthcare worker or family member), group specifications (e.g., hospitalization status or type of isolation), level of complexity (with two levels differentiated by symptom severity: Level I for less complex cases and Level II for cases requiring calls lasting more than 20 min or involving intense emotional expression or worrisome symptoms), predominant symptoms and emotions experienced by patients; type of intervention carried out; patient outcomes; number and duration of telephone interventions. All professionals who completed the template form were adequately instructed in specific training for its proper completion.

Psychologists specializing in clinical psychology conducted this single-center study during the COVID-19 pandemic. The program implemented a new approach to treatment by transitioning from face-to-face to remote consultations using telemedicine. During PASMICOR’s implementation, short-term, problem-focused telephone interventions were coordinated with the aim of producing rapid and effective change in patients. There were 12 part-time clinical psychologists and 2 part-time Resident Internal Psychologists, while 4 full-time psychiatrists were available to provide care for second-level users. At the sixth month, three more clinical psychologists were recruited to strengthen the program and the part–time psychologist came back to their usual works and clinics.

After 9 months of data collection, an interim study was analysed and showed that fear was a predominant emotion among healthcare workers while sadness and feelings of helplessness were more common among patients. Fear and sadness were also prevalent among family members17. The most effective treatments included techniques related to emotional expression and regulation as well as self-care. Mindfulness was particularly effective among healthcare professionals while grief counselling and providing information about available resources were beneficial for family members17. After 18 months of follow-up the program was closed, and no new patient were admitted since October. Patient who needed more follow-ups were referred progressively to the Salamanca mental health network until December 2021 this study analysed all available data and evaluated the overall effectiveness of the PASMICOR program.

Data analysis

To assess the impact of the program on hospital burden detailed information about these tests, along with the data collection questionnaire, is included in an appendix document (see supplementary material) for reference. This analysis employs data gathered through the questionnaire detailed in the supplementary material, which provides a comprehensive overview of the variables considered and the statistical tests applied. The analysis and reporting of sociodemographic variables of program participants will be as frequencies and percentages. Median, mean, and standard deviation statistics will describe intervention characteristics. A frequency table showing the characteristics of program participants will present patient outcomes.

Analyses were conducted on the data collected in the supplementary material. For the analyses, the number and duration of calls, levels, and other variables recorded were related. Please refer to the attached document.

Pearson correlations will be calculated and reported along with their corresponding p-values. To analyze percentage increases, contingency tables were constructed using Kramer’s χ2 and Phi and V statistics. The calculation of corrected residuals identified significant differences between cells; values outside ± 1.96 were considered significant. SPSS performed statistical analyses19. Non-parametric tests such as the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were employed in our analysis.

Finally, a profile of program participants will be presented to determine whether there are differences in call duration or frequency based on factors such as gender, age, or type of user. A p-value < 0.05 will be considered statistically significant for these analyses.

Ethical standards

This project was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Salamanca Health Care Complex under the code: GRS59/A/20. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, the appropriate measures have been taken to guarantee the complete confidentiality of the personal data of those participating in this study and in accordance with the "Organic Law 15/1999 of 13 December on the Protection of Personal Data" of the Government of Spain, under the protection of Law 41/2002 and in particular article 6.2 on the use of clinical documentation.

Results

Participant principal characteristics

A total of 216 individuals were included in the program, with an average age of 53.92 years and ranged in age from 10 to over 90 years old, with the majority being between 51 and 60 years old. Of these participants, 167 (77.3%) were women. Most participants were either employed or unemployed at the time of enrolment. Similar proportions of healthcare workers and individuals affected by COVID-19 received care through the program, with slightly fewer family members receiving care. Table 1 presents the frequencies of participant characteristics.

Type of user: health workers, patients and/or relatives

In terms of group membership, healthcare workers made up 36.1% (78 participants) of the program, COVID-19 patients made up 35.2% (76 participants), and relatives of COVID-19 patients made up 28.7% (62 participants). The proportion of healthcare workers, COVID-19 patients or family members participating in the program did not change significantly over time. All groups received similar proportions of interventions (p = 0.491). However, healthcare workers categorized as level-2 received 24.9% more interventions than family members (p = 0.004). Despite family members receiving twice as many interventions as COVID-19 patients and 1.4 times more than healthcare workers, there were no significant differences in the number (p = 0.071) or duration (p = 0.091) of calls between groups.

Evolution

Of the patients who met their treatment objectives and were discharged, 5 were readmitted to the program for continued care: 3 during the first 9 months and 2 during the second 9 months. An additional 5 patients did not continue with the program due to death. The program ran for a duration of eighteen months, plus two additional months for discharge period; during which we provided assistance to all participants who sought it. The program ensured that all participants received complete care. 21 participants (9.7%) were referred to the Salamanca mental health care network.

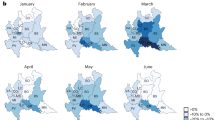

Temporal correlation: hospital burden and PASMICOR admissions

There was no significant correlation between PASMICOR admissions and the number of positive COVID-19 cases in Salamanca (r = 0.392, p = 0.058). However, PASMICOR admissions moderately correlated with admissions to the Intensive Care Unit (r = 0.533, p = 0.007) and strongly correlated with hospitalizations (r = 0.737, p < 0.001) and deaths (r = 0.775, p < 0.001) due to COVID-19 (Fig. 1).

Comparison of COVID-19 Incidence and Hospital Care Services in the Province of Salamanca with Admissions to the PASMICOR Program. ICU Intensive Care Unit. Data obtained from1.

Intervention characteristics results

We conducted a total of 1376 interventions over the course of the PASMICOR program, totalling 730 h of telephone-based care. Each intervention lasted an average of 31.8 min. The duration and frequency of interventions varied considerably, ranging from brief, single interventions lasting 10 min to more extensive treatment involving up to 38 interventions and over 27.5 h of telepsychology assistance. From admission to discharge, each patient required a median of 4 calls (mean = 6.36, SD = 6.37) and a median of 120 min of telephone-based care (mean = 202.73, SD = 241.83).

Women received more interventions (mean = 7.06, SD = 6.88) and longer total intervention duration (mean = 234.97, SD = 265.23) than men (mean = 4.60, SD = 4.06; p = 0.016 and mean = 119.91, SD = 114.67; p < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, individual intervention sessions lasted longer for women, with an average duration of 32 min compared to 26 min for men (p = 0.005). Women also received 18.3% more level-2 interventions than men (p = 0.012).

The age distribution of program participants was not normal (p < 0.001). Most participants were between 51 and 60 years old (27.8%). On average, healthcare workers were younger than COVID-19 patients or their family members (p < 0.001). Age group was not significantly associated with the number of calls received by participants (p = 0.604) or with call duration (p = 0.166). Among participants aged 81–90, the number of level-1 interventions was lower than expected (Zfixed = − 2.1). Notably, the majority of participants (79.6%) received comprehensive care through the program, 9.7% were referred to Psychiatry or Psychology services (where they receive mental health face to face treatment as suggested by the professionals in charge) and 6% refused treatment or deceased and a 4.6% of missing data. User characteristics can be seen in Table 2.

Interventions, emotions, and symptoms

Among program participants, the most commonly reported symptoms were anxiety, insomnia, and crying (Table 3). At the end of the program, we did not monitor any subject, since we discharged or referred all users. Notably, during any of the interventions, we did not record substance abuse as a coping mechanism.

Discussion

The PASMICOR program successfully addressed the increased demand for mental health services resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic in the province of Salamanca. Since 79.6% of participants received comprehensive care through the program without requiring referrals to other services, we consider that the program effectively met the majority of participants’ needs.

It is notable that COVID-19 patients, family members, and healthcare workers participated in the program in similar proportions. Healthcare workers were the most numerous group, which may be due to targeted advertising in healthcare facilities and to this group being particularly affected by mental health issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Consistent with previous research20, men were less likely to seek mental health care through the program. This suggests that we may need a more proactive approach to encourage men to seek help when needed21. One possible explanation for why female healthcare workers received more care through the program is that women are overrepresented in healthcare professions. All of this leads to gender disparities being sustained and increasing with crises22.

The age distribution of program participants did not align with the population group most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic23, due to the specific inclusion criteria of the program mentioning before. Few participants were residents of nursing homes, as their symptoms were not severe enough to require mental health treatment. We did not include healthcare workers over the age of 65 in the program, as they exceeded the retirement age limit. However, there was greater variability in the ages of family members, as we applied no age restrictions to this group.

We initiated the PASMICOR program in response to increased demand for mental health services in order to avoid an overbooking of new patiens in the already existing mental health network. The program began after a few weeks as a rapid response to the health emergency. Despite this, the severity of the symptoms found was high, showing that it was high from the beginning as observed in other mental health interventions24,25,26,27. As a free intervention, the program removed access barriers for vulnerable communities25. Other studies have highlighted social isolation and worsening pre-existing mental disorders as key issues during the pandemic24. Depression, anxiety, and stress are common emotions experienced during this time28, and while recovery from these symptoms has been observed, overall mental health remains poor among many individuals29. Globally, first reports indicates that suicide rates did not increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, but there was a higher lethality among 65 years old retired employment males30,31,32. We corroborate findings from other studies33 that the utilization of telemedicine proves successful, with no specific complaints from users or program professionals. This underscores the effectiveness of non-face-to-face interventions, which not only maintain effectiveness but also mitigate the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Additionally, in our case, telemedicine interventions could explain why we recorded no completed suicides or low rates of suicidal thoughts or ideation among program participants. Another possible explanation is that we referred individuals at risk for suicide to psychiatric care. As limitations of this study, the types of therapy or the approach offered may have varied depending on the group or on the psychologist assigned to each patient. Because healthcare professionals facilitated access to the program during an emergency situation, it is possible that only extreme cases were referred for treatment, as some individuals may have avoided seeking care at healthcare facilities due to fear of contagion. All referred patients were able to speak, so there were not severe COVID-19 cases. The absence of prior mental health recordkeeping could have influenced the study outcomes, potentially skewing the results. Finally, it is noteworthy that the program was only applied in Salamanca, being configured as a single area, and it is possible that the mental health network was different in other areas of the country. However, this is a real-world experience that should be taken into account for planning. It provides an immediate and medium-term response to critical situations such as a pandemic and shows that few patients were readmitted or referred to the mental health network.

This study provides valuable information on the demand for real word mental health care during a national emergency situation and on common symptoms and emotions experienced by individuals affected by COVID-19 without filters. It also provides insight into the types of interventions used and the personnel and time required to meet demand. We found telepsychology to be an effective form of care delivery that could prevent the normal mental health network from collapsing. We were able to discharge a small portion of the patients progressively. Since few participants required repeat treatment, we can consider that the program successfully met their needs. Similar programs have been implemented elsewhere, but data on their management and effectiveness are not available. We point out that we referred few participants to standard mental health services when the program ended.

As recommendations for improvement, we suggest assigning dedicated staff to the program from the start to avoid overloading professionals who are also responsible for other duties. It would be useful providing adequate training to psychologists could help shorten intervention duration, and increase the number of patients served. Additionally, providing therapy for program staff, such as defusing and debriefing, may also be beneficial. For future interventions, it may be beneficial to focus more on women and other groups most affected by the pandemic.

Data availability

Data are available from the correspondence author, upon request. Data are not publicly available due to ethical issues.

References

Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar social. Situación COVID-19 en España. [Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare. COVID-19 situation in Spain]. Accessed 19 October 2022; https://cnecovid.isciii.es/covid19/

Soriano, J. B., Peláez, A., Fernández, E., Moreno, L. & Ancochea, J. The emergence of COVID-19 as a cause of death in 2020 and its effect on mortality by diseases of the respiratory system in Spain: Trends and their determinants compared to 2019. Arch. Bronconeumol. 58, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2022.03.001 (2022).

Manchia, M. et al. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 55, 22–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.10.864 (2022).

Deng, J. et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1486(1), 90–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14506 (2021).

Goldberg, X. et al. Mental health and COVID-19 in a general population cohort in Spain (COVICAT study). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 57(12), 2457–2468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02303-0 (2022).

González-Sanguino, C. et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 (2020).

Alonso, J. et al. Mental health impact of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers: A large cross-sectional survey. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud. Ment. 14(2), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.12.001 (2021).

Li, W. et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16(10), 1732–1738. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.45120 (2020).

Fond, G. et al. Association between mental health disorders and mortality among patients with COVID-19 in 7 countries. JAMA Psychiatry 78(11), 1208. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2274 (2021).

Andrés-Olivera, P. et al. Impact on sleep quality, mood, anxiety, and personal satisfaction of doctors assigned to COVID-19 units. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(2712), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052712 (2022).

Della Monica, A. et al. The impact of Covid-19 healthcare emergency on the psychological well-being of health professionals: A review of literature. Ann. Ig 34(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2021.2445 (2022).

Asper, M. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and previous pandemics, epidemics and economic crises on mental health: systematic review. BJPsych. Open 8(6), e181. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.587 (2022).

Guan, W. et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. England J. Med. 382(18), 1708–1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 (2020).

Martin, C. et al. COVID pandemic as an opportunity for improving mental health treatments of the homeless people. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 67(4), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020950770 (2021).

Hossain, M. M. et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Res 9, 636. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.24457.1 (2020).

Mendonça, I., Coelho, F., Ferrajão, P. & Abreu, A. M. Telework and mental health during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(5), 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052602 (2022).

Roncero, C. et al. The challenge of community mental health interventions with patients, relatives, and health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A real-world 9-month follow-up study. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 20996. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25297-w (2022).

Roncero, C. et al. Healthcare professionals’ perception and satisfaction with mental health tele-medicine during the COVID-19 outbreak: A real-world experience in telepsychiatry. Front. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.981346 (2022).

I. SPSS Corp., IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v.25. Armonk, IBM Corp.

Brotto, L. A. et al. The influence of sex, gender, age, and ethnicity on psychosocial factors and substance use throughout phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 16(11), e0259676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259676 (2021).

Sagar-Ouriaghli, I., Godfrey, E., Bridge, L., Meade, L. & Brown, J. S. L. Improving mental health service utilization among men: A systematic review and synthesis of behavior change techniques within interventions targeting help-seeking. Am. J. Mens. Health 13(3), 155798831985700. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988319857009 (2019).

Morgan, R. et al. Women healthcare workers’ experiences during COVID-19 and other crises: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 4, 100066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2022.100066 (2022).

Na, L., Yang, L., Mezo, P. G. & Liu, R. Age disparities in mental health during the COVID19 pandemic: The roles of resilience and coping. Soc. Sci. Med. 305, 115031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115031 (2022).

Sheridan Rains, L. et al. “Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 56(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01924-7 (2021).

Witteveen, A. B. et al. Remote mental health care interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review. Behav. Res. Therapy 159, 104226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2022.104226 (2022).

Mediavilla, R. et al. Mental health problems and needs of frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A qualitative analysis. Front. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.956403 (2022).

Davison, K. M. et al. Interventions to support mental health among those with health conditions that present risk for severe infection from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A scoping review of English and Chinese-language literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(14), 7265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147265 (2021).

Jin, Y., Sun, T., Zheng, P. & An, J. Mass quarantine and mental health during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 295, 1335–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.067 (2021).

Cénat, J. M. et al. The global evolution of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Affect Disord. 315, 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.011 (2022).

Yan, Y., Hou, J., Li, Q. & Yu, N. X. Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(4), 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043346 (2023).

Aknin, L. B. et al. Mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A review and recommendations for moving forward. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 17(4), 915–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211029964 (2022).

García-Ullán, L. et al. Increased incidence of high-lethality suicide attempts after the declaration of the state of alarm due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Salamanca: A real-world observational study. Psychiatry Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114578 (2022).

Rutkowska, A. Telemedicine interventions as an attempt to improve the mental health of populations during the COVID-19 pandemic—A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(22), 14945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214945 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The writing of this study has been possible thanks to the assistance, willingness and dedication of a large part of the clinical psychology and psychiatry professionals of the Psychiatry Service of the University of Salamanca Health Care Complex, namely: Ana Ojeda Escuín, Laura Alonso León, Ana González Gil, Virginia Dútil de la Torre, Pablo Gutiérrez Álvarez, Vanessa Martín Muñoz, Francisco del Castillo de la Torre, Susana Fernández de la Vega, José Ángel Herrero García, Marta Morales Ramirez, Ascension Gallego Nogueras, Santiago Ignacio Sánchez Iglesias, Ana Isabel Álvarez Navares y Carolina Concepción Lorenzo Romo.

Funding

This work has been funded by the Castilla y León Regional Health Management (Spain) file no.: GRS COVID59/A/20 “Impacto y abordaje de salud mental en familiares y pacientes afectos de COVID y en los profesionales sanitarios” (Impact and management of mental health in relatives, patients affected by COVID and health professionals). All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this study. The funding entities had no role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, in the process of writing the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R. and J.A.B.S. conceptualization, methodology and project administration; C.R., A.G.-S. data curation and formal analysis; C.R., funding, acquisition, and supervision; C.R., A.G.S, S.D.T., E.A.L., M.B.P., E.A.-L., Ll.G.-U., and J.A.B.S. writing and preparation of the original draft, writing, review, and editing. C.R. and A.G-S. Are equal contributors to this work and designated as co-first authors; All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roncero, C., Díaz-Trejo, S., Álvarez-Lamas, E. et al. Follow-up of telemedicine mental health interventions amid COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 14, 14921 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65382-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65382-w