Abstract

The study reports on the magnetization, magnetoresistance, and transport properties of superparamagnetic 10% Co-doped Ni/NiO (C10-NN), Graphene Oxide (GO) incorporated 10% Co-doped Ni/NiO (C10-NNG), and 15% Co-doped Ni/NiO (C15-NN) nanoparticles synthesized via a microwave-assisted sol-gel auto-combustion method. All samples show hysteresis in negative Magnetoresistance (M-R) at different temperatures. Resistivity ρ(T) versus temperature plots of samples C10-NN and C15-NN show metallic behavior with applied fields of 0, 1, 5, 8 T, and at 0 T, 1 T respectively. However, the plot of R-T of the C15-NN sample shows a significant difference at 0 T and 1 T. At 0 T for this sample, the metallic behavior is observed for temperature T > TM, with the resistivity falling abruptly at and above TM = 246 K. The resistivity decreases with increasing temperature, exhibiting metallic behavior again above TMM < 276 K. This jump at 276 K, indicating a metal-to metal transition. The Kondo effect is observed for the first time in C10-NNG sample. The upturn of resistivity ρ(T) towards low temperature in the C10-NNG sample is well described by the power series equation and Kondo term. This sample exhibits the upturn resistivity along with a metal–insulator transition above and below the Kondo temperature TK ≈ 93.51(2) K at the 0 T, 1 T, 5 T, and 8 T fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, spintronics is one of the leading research fields in condensed matter physics, focusing on magnetic materials1. The influence of spin on conduction, achieved through processes such as ejection, extraction, transfer, polarization, and accumulation within magnetic nanostructures, leads to the field of spintronics. This field finds applications in various technologies, including giant magnetoresistance (GMR), tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR), and others. The study of magnetotransport, magnetoresistance, and magnetic properties of ferromagnetic/antiferromagnetic materials is of significant technological and scientific interest2,3. The magnetic ordering observed in itinerant ferromagnetism of transition metals such as Ni, Co, and Fe is closely tied to electron correlation within narrow 3d bands. These bands only weakly hybridize with the 4s and 4p bands. Due to the strong spatial confinement of d-orbitals, the spin-polarized electrons, resulting from exchange interaction with uncompensated magnetic moments of completely localized d electrons, predominantly contribute to the transport properties4. Ni-NiO is known for its magnetic properties, and doping with Co can enhance these properties by introducing additional magnetic moments and improving spin polarization5.

The Kondo effect occurs when conduction electrons in a metal scatter due to low-density magnetic impurities, resulting in spin-flips by localized spins. This phenomenon leads to dramatic effects on the upturn of electrical resistivity as temperature decreases and increases6,7,8. When a magnetic impurity is placed on metal surfaces, the Kondo interaction between the localized spin and the conduction electrons becomes very strong, resulting in high Kondo temperatures (TK)6,7,8. The antiferromagnetic coupling between itinerant electrons and localized spins leads to the screening of impurity spins, thereby manifesting the Kondo effect.

The Kondo effect, a key phenomenon in condensed matter physics, has seen significant advancements that enhance our understanding and applications. Recent research using an artificial atom and a one-dimensional wire system has confirmed theoretical predictions by observing the Kondo resonance at extremely low temperatures, opening new possibilities for studying exotic quantum phenomena9. The discovery of the three-channel Kondo effect in cubic holmium compounds offers new insights into non-Fermi liquids and quantum materials10. Additionally, research on quantum impurity systems have demonstrated novel thermoelectric behaviors, manipulating local temperatures through applied voltages, thus advancing our understanding of nanoscale heat flow11. These developments deepen our understanding of the Kondo effect and pave the way for future explorations in quantum materials and strongly correlated electron systems. This phenomenon has been observed in various materials, including metal oxides, dilute magnetic alloys, semiconductor quantum dots, nickelates, carbon nanotubes, and graphene12,13,14,15,16.

Numerous experimental and theoretical investigations have been conducted to explore the occurrence of upturns in electrical resistivity while decreasing and increasing temperature. It has been observed that various phenomena are involved, such as spin-polarized tunneling via grain boundaries17,18, Kondo effects19,20, quantum interference effects due to electron-electron interactions20,21, and weak localization effects22. In terms of systems that manifest the Kondo effect, it is noteworthy that there have been no reports yet on the Kondo effect in S2 sample. GO was chosen due to its excellent conductivity and large surface area, which can enhance the overall conductivity of the composite material. Furthermore, GO provides a platform for better dispersion and stabilization of nanoparticles, which is essential for maintaining uniform magnetic properties23. The Kondo effect has been observed in graphene via cobalt adatoms on a graphene monolayer23,24, graphene with defects25, and spin-orbit coupling in graphene quantum dots26. Kondo effect has also been observed in atomic contacts of pure itinerant ferromagnetism, with coexistence of FM and Kondo states26,27, and in heavy-fermion metals28,29.

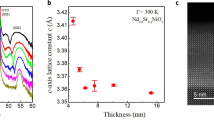

In the present paper, we systematically investigated the magnetic (M-T, M-H) and transport (R-T, R-H) properties of superparamagnetic nanoparticles of samples C10-NN, C10-NNG and C15-NN synthesized via a microwave-assisted sol-gel auto-combustion method. Interestingly, we observed a pronounced low-temperature resistivity upturn in the C15-NN sample. Furthermore, we found that this sample exhibited a large Kondo temperature (TK ≈ 93.51(2) K). Magnetoresistance measurements of the synthesized samples revealed negative M-R with hysteresis at different temperatures. The results of Raman shift, XRD and HR-TEM evaluated for structural and elemental analysis (provided in supplementary information figs. SI1, SI2, SI3 respectively).

Result and discussion

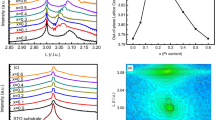

The magnetic properties were measured from the magnetic hysteresis curve (M-H) at temperatures from low (30 K) and room temperature (300 K) for the samples, as shown in fig. 1. The M-H curve reflects a sharp increase in magnetic moments with the applied field, which then begins to saturate at H = 0.45 ± 0.05 T. From fig. 1, it is observed that the saturation magnetization (MS) values are 35.01, 20.08, and 16.21 emu/g at 30 K, and 33.18, 18.67, and 14.49 emu/g at 300 K for C10-NN, C10-NNG and C15-NN samples, respectively. It is confirmed that the MS decreases with an increase in temperature and also decreases with increasing cobalt content. The presence of MS indicates a large contribution of metals like Ni and Co present in the samples. The decrease in the values of MS for the samples is a result of surface interfacing with the ferromagnetic (FM) Ni, antiferromagnetic (AFM) Co-NiO layer, GO, and surface spin/disordered magnetic spin orientation, which are significantly responsible29,30,31. The obtained MS value of the samples is significantly less than the value of bulk Ni MS, which is about 55 emu/g32. It is noticeable from fig. 1 that all samples saturate with the applied magnetic field, but no remanence magnetization (MR) or coercivity (HC) (MR and HC = 0) appears, confirming their superparamagnetic state29,30,31,32. The nonlinear nature of the M-H curve further confirms this state. The superparamagnetic state is expected due to the small size and single domain nature of the as-synthesized nanoparticles.

Figure 2a–c present the variation of magnetization as a function of temperature for the as-synthesized samples under both zero field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC) conditions, with an applied magnetic field (Ha) of 500 Oe, ranging from temperatures of 3 K to 350 K. In the FC plot, the magnetization data shows an increasing behavior from high to low temperature ranges, while in the ZFC plot, the magnetization first monotonically increases, then slightly decreases with increasing temperature. During cooling in ZFC, the magnetization reaches a maximum value at approximately 251 K, 265 K, and 281.5 K for C10-NN, C10-NNG and C15-NN samples, respectively, indicating the blocking temperature (TB). It is noticed that the TB increases, which may be attributed to the exchange coupling between ferromagnetic (FM) Ni/Co and antiferromagnetic (AFM) NiO components, implying improved thermal stability33,34. This type of exchange coupling established at the Ni and Co-NiO interface provides a platform to enhance TB and magnetic stability35,36,37. Additionally, the enhancement of TB has several reasons, such as broad size distribution, particle agglomeration, or strong interparticle dipolar magnetic interactions38,39. The irreversible temperature in the ZFC-FC curve of the samples C10-NN and C10-NNG is observed at 348 K but for C15-NN, the irreversible temperature is above 348 K, indicating ferromagnetic behavior. The splitting (bifurcation) of the ZFC and FC curve usually appears in the co-existence of antiferromagnetic (NiO) and ferromagnetic (Ni/Co) phases coinciding with the synthesis of nanoparticles35,36,37,38,39. Many authors have reported that a sharp cusp is observed at low temperature on the ZFC curve, demonstrating a freezing temperature (Tf), which freezes the ferromagnetic (Ni/Co) spins and the antiferromagnetic (NiO) spin moments, signifying a spin-glass-like state. In this case, a spin-glass-like state or frozen spin is not observed at low temperatures; however, as the temperature increases, the magnetic moments progressively unfreeze. However, the AFM domain gives rise to strong spin scattering, resulting in high resistivity.

The resistivity measurement as a function of the applied magnetic field (H) was conducted on strip-shaped pellets of as-synthesized samples with dimensions approximately 3 × 2.5 × 0.25 mm3 (length × width × thickness). Figure 3a–c depicts the MR (%) curve of the longitudinal magneto-resistance configuration for sample C10-NN at temperatures of 5 K, 10 K, 50 K, and 100 K. Additionally, samples of C10-NNG and C15-NN were measured at applied magnetic fields of ± 8 T for temperatures of 5 K, 50 K, and 100 K, with the magnetic field and current parallel to each other. Here, the field-dependent MR(%) is defined as MR(H)% = [\((\frac{\rho \left(H\right)}{\rho \left(0\right)}-1)\times 100]\), where ρ(H) and ρ(0) are the resistivity under the applied magnetic field H and zero applied magnetic field, respectively. From fig. 3a–c, it is evident that the resistivity decreases gradually with increasing magnetic fields (resulting in negative MR) in all samples at different temperatures. This trend indicates that the antiferromagnetic (AFM) state of NiO is gradually transitioning into the ferromagnetic (FM) state. As the FM ordering becomes complete, the negative MR saturates, reaching magnitudes of approximately − 0.65, − 0.89, and − 0.78% at 100 K for the C10-NN, C10-NNG and C15-NN samples, respectively. However, it’s worth noting that the AFM domain contributes to strong spin scattering, leading to higher resistivity40,41,42. Nevertheless, such spin scattering can be suppressed when the system is forced into the FM phase by applying external magnetic fields41,42,43. In this case, the NiO in the samples is in the amorphous phase and Ni/Co in the crystalline phase; hence AFM contributes less to spin fluctuation. Thus, ρxx(T) decreases with increasing fields. The results of magnetic scattering via spin fluctuations of the localized spins in response to the applied magnetic field give rise to magnetoresistance. In the saturated (single-domain) state at room temperature, the resistivity depends only on the relative orientation of the magnetization and the measuring current41,42,43. In the negative magnetoresistance, the reduction of resistivity with increasing magnetic field in the saturation region is due to the suppression of the thermally-induced spin-disorder contribution to the resistivity43,44,45, with the scattering of conduction electrons occurring at given temperatures. As depicted in fig. 4a,b, the M-R(%) curve exhibits hysteresis behavior when the magnetic field reverses from forward to backward sweep at 100 K for samples C10-NN and C10-NNG, and at 5 K and 10 K for C15-NN sample. However, it is observed from fig. 4a,b that the M-R curve exhibits no hysteresis behavior at 5 and 10 K for sample C10-NN; and 5, 10 and 50 K for sample C10-NNG, and at 100 K for sample C15-NN respectively. This absence of hysteresis is attributed to transport being solely carried out by the surface states. A parabolic negative M-R (%) is observed, which is attributed to the decrease in spin-related scattering with increasing magnetic field43,44,45. Interestingly, fig. 3a shows strong hysteresis at all magnetic fields below saturation at 100 K temperature. The presence of hysteresis in MR (%), with no corresponding hysteresis observed in magnetization from fig. 1, is due to the lack of hysteresis in the magnetization observed at 100 K. Sunku et al. reported that hysteretic magnetoresistance may arise from complex structures at magnetic domain walls46.

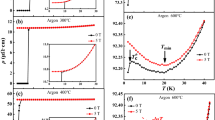

The temperature-dependent longitudinal electrical resistance, represented as ρxx(T), was evaluated at various applied magnetic fields ranging from 0 to 8 T for samples of C10-NN and C10-NNG as illustrated in fig. 3d–f. For the C15-NN sample, measurements were conducted at magnetic fields of 0 T and 1 T. The C10-NN sample exhibits metallic behavior above 100 K temperature, with increasing resistance at a given field. However, the sample of C10-NNG show a different behavior: initially, as the temperature decreases, the resistivity decreases, reaching a minimum around 100 K, and then it increases again. This upturn of electrical resistivity with temperature is attributed to the presence of magnetic/metallic impurities, which induce an increase in resistance at low temperatures. This unusual phenomenon is explained by the Kondo effect, which arises due to the interaction between the host conduction electrons and the magnetic impurity. This interaction leads to a logarithmic increase in electrical resistivity as the temperature decreases.

The presence of G and D bands of GO seen in the SI fig. SI2 and HR-TEM micrographs is provided in SI fig. SI3e–g indicate that the nanoparticles are coated or wrapped by graphene oxide (GO), facilitating the interaction of magnetic ions of Co/Ni with the GO conduction electrons, thus revealing the Kondo effect. The observation of a minimum in the resistivity-temperature relationship ρ(T) is characteristic of the Kondo effect and is attributed to the combined effects of electron-electron (e-e) and electron-phonon (e-p) interactions, as well as spin scattering of the conduction electrons by the magnetic impurity.

The total electrical resistivity of the metal is given by:

where, \({\rho }_{0}\) is the residual resistivity and \({\rho }_{i}(T)\) intrinsic resistivity.To account for the upturn resistivity observed in the sample (C10-NNG), a kondo term ρK has been added:

The \({\rho }_{i}\left(T\right)\) is described by the Bloch-Gruneissen expression arise47 due to electron-phonon interactions:

where α is a constant depending on electron-phonon coupling, Debye frequency, and plasma frequency, ΘD is the Debye temperature, and n takes values of 2, 3, or 5 depending on the interaction nature. The equation for total resistivity then becomes:

The residual resistivity ratio defined as \({\raise0.7ex\hbox{${{\uprho }\left( {300K} \right)}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\uprho }\left( {300K} \right)} {{\uprho }\left( 2 \right)}}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${{\uprho }\left( 2 \right)}$}}\) is relatively small it estimated to be 0.02814 ± 6.13 × 10−5, 0.0275 ± 3.1 × 10−5, 0.0276 ± 1.85 × 10−5and 0.02796 ± 3.2 × 10−5 Ω-cm for sample S3 at 0 T, 1 T, 5 T and 8 T respectively.

In general, the resistivity versus temperature behavior can be modeled by another equation with contributions from a metallic term \(A{T}^{n}\) and an insulating term \({\rho }_{I}\left(T\right)\)48:

where, \(A{T}^{n}\) represents metallic resistivity of power law with n = 1, 2, or 5. Different values of n indicate various contributions such as charged-impurity resistivity (for n = 1), standard metallic Fermi-liquid behavior (for n = 2), and lattice vibration contributions (for n = 5)48,49, and \({\rho }_{I}\left(T\right)\) represents the insulating term which can be analyzed using different models such as Kondo effect, Mott variable-range hopping, weak localization, etc.49,50.

The Bloch-Grüneissen relation can be replaced by the temperature dependence of total resistivity as a power series equation:

where the first term (a0) is residual resistivity, the second and third terms belong to electron-electron resistivity, and the remaining terms belong to electron-phonon resistivity. From eqs. (5), (7) is obtained using the first five terms of the power series equation for fitting the obtained data are shown in fig. 3d–f,

It is observed that the best fit is obtained by employing eq. (5) for C10-NNG sample at different field strengths (0, 1, 5, and 8 T), with statistical parameters (as reduced χ2 = 2.416 × 10−9, 6.364 × 10−10, 2.2718 × 10−10, 6.903 × 10−10 and coefficient of determination r2 = 0.997, 0.999, 0.999, 0.999 respectively) showing high accuracy.

Figure 3d,f for the sample of C10-NN at 0 T to 8 T and S3 at 1 T field reveals the metallic nature and is best fitted with eq. (4) without adding an insulating term. From fig. 3e, at 1 T and 5 T fields, the resistivity remains the same at 0.0233 Ω-cm with the same Kondo temperature at 93.51 K, while for 0 T and 8 T, the resistivity values of 0.0238 and 0.0236 Ω-cm decrease with temperature at 91.75 K and 90.24 K, respectively. From fig. 3f, the sample of C15-NN shows a different resistivity nature at 0 T and 1 T field. Upon heating without an applied field (0 T field), the sample shows metallic behavior of the resistivity; it rises slowly at (T < TM) 246 K temperature. It means that below TM = 246 K temperature, the resistivity slightly decreases with increasing temperature. It is noticed that upon heating, the resistivity sharply drops at the transition temperature of 246 K as a result of the amorphous-to-crystalline phase transition, and the crystalline structure is retained until the end of the thermal treatment at 276 K when complete transformation is achieved.One can immediately observed from fig. 3f that a resistivity jump at TMM = 276 K, indicating a metal to metal transition (MMT). Attempts for fitting this resistivity by using eq. (6) do not match with resistivity of metallic nature51 due to MMT. However, the sample exhibits metallic nature while applying a 1 T magnetic field with temperature, indicating that the crystalline structure is retained and electron alignment opposes the magnetic field. Overall, it is noticed that samples of C10-NN and C10-NNG exhibit resistivity increases with applied field. The R-T plot of C15-NN shows the resistivity jump shifts to a lower value at 225 K temperature without applying a field (0 T).

The first derivative of resistivity plot as a function of temperature dρ/dT and temperature are shown in fig. 4a indicates metallic nature of C10-NN above 24.37 K temperature. The temperature dependence of the resistivity exhibits a metal–insulator transition at temperature under 0, 1, 5 and 8 T field as shown in fig. 4b. It could be more clearly reflect in dρ/dT as shown in fig. 4b. It indicates below TMI≈91.51(5) dρ/dT is negative resulting insulating behavior51,52,53,54. In particular, as the temperature approached to the TMI, resistivity modulation by electric field was greatly increased presumably due to the coexistence between metallic and insulating phase near TMI. It is noted from fig. 4c that the C15-NN samples reflect the pure metallic nature 0 T field. But at the 1 T filed it sowing metallic at TMI > 240.54 K, after it shows insulating state (negative dρ/dT) two peak of TI1 and TI2 at 257.62 and 274.31 respectively51,52,53,54.

Conclusions

The superparamagnetic samples of C10-NN, C10-NNG and C15-NN were synthesized via microwave-assisted sol-gel auto-combustion method. It is confirmed from the M-R data that the samples exhibit negative magnetoresistance and hysteresis in magnetoresistance. The resistivity (ρ) versus temperature (T) plots show metallic behavior with applied fields of 0, 1, 5, and 8 T for sample C10-NN, and 1 T for C15-NN sample. At 0 T, the sample of C15-NN exhibits metallic behavior up to T > TM (TM = 246 K), with the resistivity falling abruptly above TM. The resistivity decreases with increasing temperature and again shows metallic behavior above T < 276 K. The upturn of resistivity (ρ) versus temperature (T) towards low temperature of the C10-NNG sample is well described by the power series equation and Kondo term. The dρ/dT versus temperature plot indicates a metal-insulator transition at applied fields of 0, 1, 5, and 8 T for C10-NNG sample. The results contribute to understanding the underlying mechanisms driving these behaviors and suggest potential applications in spintronics devices and magnetic sensors. Future research should focus on exploring the precise role of graphene oxide and optimizing doping levels to tailor the properties of these materials for specific applications.

Experimental details

A microwave-assisted sol-gel auto-combustion method55 was employed for the synthesis of Co-substituted NiO/Ni nanoparticles. During the synthesis of the samples, analytical-grade nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O), cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O), citric acid monohydrate (C6H8O7·H2O) as fuel, and distilled water (solvent) were used without any further purification. We used a reducing atmosphere during synthesis to preferentially oxidize Ni while reducing the likelihood of Co oxidation. This method ensures that Co predominantly dopes into the NiO sites rather than forming CoO. Samples of 10% Co-doped Ni/NiO (C10-NN), GO incorporated 10% Co-doped Ni/NiO (C10-NNG), and 15% Co-doped Ni/NiO (C15-NN) of Ni/CoxNi1-xO (x = 0.10 and 0.15) were synthesized using the appropriate amounts of nickel nitrate hexahydrate (1-x mmol), cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (x mmol), and citric acid monohydrate (2 mmol). Each component was dissolved separately in 100 mL of distilled water and stirred for 1 h in a 500 ml beaker. Then, the citric acid solution was added dropwise into the precursor solutions mentioned above. The solution was stirred for 2 h at 40 °C until a clear solution was formed. Subsequently, the solution was stirred and evaporated for some time at 200 ℃ on a hot plate, allowing gelling formation. During the gelling process, the beaker was placed inside a microwave oven and heated through microwave irradiation for 10 s for 10 cycles at an output power of 800 W and a frequency of 2.45 GHz. Microwave irradiation converted the obtained viscous gel into foam, which ignited upon irradiation, resulting in loose and burnt powder of the samples. The same procedure was applied for the C10-NNG sample, with the only difference being the addition of 10 mg GO during synthesis. Graphene oxide (GO) was prepared using a reported Hummers method by Hummers et al.56 as follows: H₂SO₄ (50 mL) was added to a mixture of graphite flakes (3.0 g) and NaNO₃ (1.5 g), and the mixture was cooled to 0 ℃. KMnO₄ (9.0 g) was added slowly in portions to keep the reaction temperature below 20 ℃. The reaction was then warmed to 35 ℃ and stirred for 30 min, at which time DI water was added slowly, producing a large exotherm to 98 ℃. The reaction was then cooled using a water bath for 10 min. After air cooling, the mixture was purified. Finally, the obtained sample powder was used for the synthesis of S2 sample.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed with Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer using wavelength of 1.5406 A0 (Cu Kα). The temperature dependence of electrical resistivity (R-T) andmagnetoresistance (R-H) was measured on 9 T-PPMS Quantum Design physical properties measurement system.The magnetic measurement of M-H and M-T was performed on Quantum Design 16 Tesla VSM. Micro-Raman shift (Horiba, LASER wavelength 532 nm) is used for local structural properties of samples.The HR-TEM images were collected at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns were acquired with a FEG-TEM (FEG Tecnai G2, F30 model). The energy dispersive spectra (EDS) were collected using a FEG-SEM.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Žutić, I., Fabian, J. & Das Sarma, S. Spintronics: Fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.76.323 (2004).

Cirillo, C. et al. Magnetotransport and magnetic properties of amorphous NdNi5 thin films. Sci. Rep. 10, 13693. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70646-2 (2020).

Moriyama, T., Oda, K., Ohkochi, T., Kimata, M. & Ono, T. Spin torque control of antiferromagnetic moments in NiO. Sci. Rep. 8, 14167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32508-w (2018).

Martinek, J. et al. Kondo effect in the presence of itinerant-electron ferromagnetism studied with the numerical renormalization group method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 247202. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.247202 (2003).

Lee, C. & Kim, D. Enhancement of spin polarization in Co-doped Ni-NiO systems. Phys. Rev. B 102, 034408 (2021).

Kondo, J. Resistance minimum in dilute magnetic alloys. Prog. Theor. Phys. 32(1), 37–49 (1964).

Otte, A. et al. The role of magnetic anisotropy in the Kondo effect. Nat. Phys 4, 847–850. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1072 (2008).

Wahl, P. et al. Kondo temperature of magnetic impurities at surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 176603. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.176603 (2004).

Van Efferen, C. et al. Modulated Kondo screening along magnetic mirror twin boundaries in monolayer MoS2. Nat. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02250-w (2023).

Hotta, T. Three-channel Kondo effect emerging from Ho ions. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 90, 113701. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSJ.90.113701 (2021).

Zeng, X. et al. Kondo cooling in quantum impurity systems. Phys. Rev. B 109, 115423. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.109.115 (2024).

Sapkota, K. R., Maloney, F. S. & Wang, W. Observations of the Kondo effect and its coexistence with ferromagnetism in a magnetically undoped metal oxide nanostructure. Phys. Rev. B 97, 144425. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.144425 (2018).

Barone, C. et al. Kondo-like transport and magnetic field effect of charge carrier fluctuations in granular aluminum oxide thin films. Sci. Rep. 8, 13892. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32298-1 (2018).

Chen, J. H. et al. Tunable Kondo effect in graphene with defects. Nat. Phys. 7, 535–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1962 (2011).

Shibata, K. & Hirakawa, K. High Kondo temperature (TK∼ 80K) in self-assembled InAs quantum dots laterally coupled to nanogap electrodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2968206 (2008).

Jin, H.-S., Pickett, W. E. & Lee, K.-W. Proposed ordering of textured spin singlets in a bulk infinite-layer nickelate. Phys. Rev. Res. 2(3), 033197. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.033197 (2020).

Mazumdar, D., Das, K. & Das, I. Spin-polarized tunneling and polaronic transport properties of polycrystalline (Sm1-yGdy) 0.55Sr0.45MnO3 (y= 0.5 and 0.7) compounds. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33(30), 305601. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/ac0386 (2021).

Kurzmann, A. et al. Kondo effect and spin–orbit coupling in graphene quantum dots. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26149-3 (2021).

Barua, S., Hatnean, M. C., Lees, M. R. & Balakrishnan, G. Signatures of the Kondo effect in VSe2. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 10964. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11247-4 (2017).

Barone, C. et al. Kondo-like transport and magnetic field effect of charge carrier fluctuations in granular aluminum oxide thin films. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 13892. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32298-1 (2018).

Zhu, L. et al. Signature of quantum interference effect in inter-layer Coulomb drag in graphene-based electronic double-layer systems. Nat. Commun. 14, 1465. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37197-2 (2023).

Niu, W. et al. Evidence of weak localization in quantum interference effects observed in epitaxial La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 ultrathin films. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 26081. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26081 (2016).

Liang, J. et al. Application of graphene oxide in enhancing the thermal conductivity of a phase change material. Sci. Rep. 11, 23843 (2021).

Ren, J. et al. Kondo effect of cobalt adatoms on a graphene monolayer controlled by substrate-induced ripples. Nano Lett. 14(7), 4011–4015. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl501425n (2014).

Chen, J. H., Li, L., Cullen, W. G., Williams, E. D. & Fuhrer, M. S. Tunable Kondo effect in graphene with defects. Nat. Phys. 7(7), 535–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1962 (2011).

Kurzmann, A. et al. Kondo effect and spin–orbit coupling in graphene quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 12, 6004. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26149-3 (2021).

Calvo, M. et al. The Kondo effect in ferromagnetic atomic contacts. Nature 458, 1150–1153. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07878 (2009).

Steglich, F. et al. Magnetism, f-electron localization and superconductivity in 122-type heavy-fermion metals. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24(29), 294201. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/24/29/294201 (2021).

Mézard, M. Spin glass theory and its new challenge: Structured disorder. Indian J. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12648-023-03029-8 (2023).

Khurshid, H. et al. Spin-glass-like freezing of inner and outer surface layers in hollow γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 5, 15054. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15054 (2015).

Kim, W. et al. Effect of NiO spin orientation on the magnetic anisotropy of the Fe film in epitaxially grown Fe/NiO/Ag (001) and Fe/NiO/MgO (001). Phys. Rev. B 81(17), 174416. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.81.174416 (2010).

Li, Z. et al. Controlled one-step synthesis of spiky polycrystalline nickel nanowires with enhanced magnetic properties. CrystEngComm 16, 8442–8448. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CE00868E (2014).

Cai, X. et al. Size-dependent structure and magnetic properties of DyMnO3 nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4895128 (2014).

Ji, J. Y., Shih, P. H., Chan, T. S., Ma, Y. R. & Wu, S. Y. Magnetic properties of cluster glassy Ni/NiO core–shell nanoparticles: An investigation of their static and dynamic magnetization. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 10, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-0925-0 (2015).

Seto, T. et al. Magnetic properties of monodispersed Ni/NiO core-shell nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 109(28), 13403–13405. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp052084+ (2005).

Levin, C. S. et al. Magnetic-plasmonic core-shell nanoparticles. ACS Nano 3(6), 1379–1388. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn900118a (2009).

Evans, R. F. L., Bate, D., Chantrell, R. W., Yanes, R. & Chubykalo-Fesenko, O. Influence of interfacial roughness on exchange bias in core-shell nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 84(9), 092404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.092404 (2011).

Salvadori, M. et al. Magnetic nanoparticles of Ni/NiO nanostructured in film form synthesized by dead organic matrix of yeast. RSC Adv. 6, 60683–60692. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ra07274g (2016).

Patange, M., Biswas, S., Yadav, A. K., Jha, S. N. & Bhattacharyya, D. Morphology-controlled synthesis of monodispersed graphitic carbon coated core/shell structured Ni/NiO nanoparticles with enhanced magnetoresistance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17(48), 32398–32412. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5cp05735d (2015).

Seemann, K. M., Hickey, M. C., Baltz, V., Hickey, B. J. & Marrows, C. H. Spin-dependent scattering and the spin polarization of a diffusive current in partly disordered L10 epitaxial FePd. New J. Phys. 12(3), 033033. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/12/3/033033 (2010).

Madduri, P. P. & Kaul, S. N. Magnon-induced interband spin-flip scattering contribution to resistivity and magnetoresistance in a nanocrystalline itinerant-electron ferromagnet: Effect of crystallite size. Phys. Rev. B 95(18), 184402. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.95.184402 (2017).

Lee, N. et al. Antiferromagnet-based spintronic functionality by controlling isospin domains in a layered perovskite iridate. Adv. Mater. 30(52), 1805564. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201805564 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Spin pumping during the antiferromagnetic–ferromagnetic phase transition of iron–rhodium. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 275. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14016-w (2020).

Bakonyi, I. Guidelines for the evaluation of magnetotransport parameters from measurements on thin strip-shaped samples of bulk metallic ferromagnets with finite residual resistivity. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133(12), 521. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2018-12351-3 (2018).

Raquet, B. et al. Magnetic resistivity and electron-magnon scattering in 3d ferromagnets. J. Appl. Phys. 91(10), 8129–8131. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1466786 (2002).

Sunku, S. S. et al. Hysteretic magnetoresistance and unconventional anomalous Hall effect in the frustrated magnet TmB4. Phys Rev. B 93, 174408. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.93.174408 (2016).

Cvijović, D. The Bloch-Gruneisen function of arbitrary order and its series representations. Theor. Math. Phys. 166, 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11232-011-0005-y (2011).

Barone, C. et al. Kondo-like transport and magnetic field effect of charge carrier fluctuations in granular aluminum oxide thin films. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 13892. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32086-y (2018).

Cava, R. J. et al. Observation of the metal-insulator transition in (TMTSF)2PF6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58(17), 1676. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.1676 (1987).

Lee, P. A. & Ramakrishnan, T. V. Disordered electronic systems. Rev. Modern Phys. 57(2), 287 (1985).

Mantovan, R. et al. Atomic-scale study of the amorphous-to-crystalline phase transition mechanism in GeTe thin films. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 8234 (2017).

Tian, Z. et al. Field-induced quantum metal–insulator transition in the pyrochlore iridate Nd2Ir2O7. Nat. Phys. 12(2), 134–138 (2016).

Heo, S. et al. Modulation of metal-insulator transitions by field-controlled strain in NdNiO3/SrTiO3/PMN-PT (001) heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 22228 (2016).

Nan, T., Liu, M., Ren, W., Ye, Z. G. & Sun, N. X. Voltage control of metal-insulator transition and non-volatile ferroelastic switching of resistance in VOx/PMN-PT heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 4(1), 5931 (2014).

Nithya, R., Ambika, S. & Ananthakumar, S. Microwave-assisted sol-gel auto-combustion synthesis of CoFe2O4/graphene nanocomposite for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. Rep. 10, 11987 (2020).

Hummers, W. S. & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1339. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01539a017 (1958).

Acknowledgements

The author extends sincere gratitude to Dr. Archana Lakhani and Dr. Rajeev Rawat of the UGC-DAE Consortium for Scientific Research, University Campus, Khandwa Road, Indore, India, for their invaluable assistance with resistivity, magnetoresistance, and VSM measurements. Special thanks to Prof. B. N. Dole, Department of Physics, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad-431004 (M.S.), India, for his scientific discussion and encouragement.

Funding

This work was supported by Kavayitri Bahinabai Chaudhari North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon-425001 (M.S.) India, via financial assistance for a research project under the Vice Chancellor Research Motivation Scheme (VCRMS) to college teachers through university funds (VCRMS Project letter No. KBCNMU/11A/VCRMS/Budget-2021-22/Sci. & Tech./146/2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UPG conducted all the work associated with data acquisition, analysis, and utilized SDKs throughout the entire process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gawai, U.P., Kamble, S.D. Signature of the Kondo effect in superparamagnetic GO incorporated Cobalt substituted Ni/NiO nanoparticles. Sci Rep 14, 24460 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67447-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67447-2

This article is cited by

-

Charge transfer processes in strontium ferromolybdate with structural inhomogeneity of intergrain boundaries

Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society (2026)

-

Asymmetric magnetoresistance and enhanced carrier transport in Ni-doped MoS2 nanosheets

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2025)