Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major global public health issue and the leading cause of death in Thailand. This study investigated the spatial–temporal association between PM2.5 and its components (organic carbon, black carbon, dust, sulfate, and sea salt) and CKD mortality in Thailand from 2012 to 2021. The Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Application version 2 (MERRA-2), a NASA atmospheric satellite model, was assessed for the temporal data of PM2.5 concentration and aerosol components. Spatial resources of 77 provinces were integrated using the Geographical Information System (GIS). Multivariate Poisson regression and Bayesian inference analyses were conducted to explore the effects of PM2.5 on CKD mortality across the provinces. Our analysis included 718,686 CKD-related deaths, resulting in a mortality rate of 1107 cases per 100,000 population where was the highest rate in Northeast region. The average age of the deceased was 72.43 ± 13.10 years, with males comprising 50.46% of the cases. Adjusting for age, sex, underlying diseases, co-morbidities, CKD complications, replacement therapy, population density, and income, each 1 µg/m3 increase in PM2.5, black carbon, dust, sulfate, and organic carbon was significantly associated with increased CKD mortality across 77 provinces. Incidence rate ratios were 1.04 (95% CI 1.03–1.04) for PM2.5, 1.11 (95% CI 1.10–1.13) for black carbon, 1.24 (95% CI 1.22–1.25) for dust, 1.16 (95% CI 1.16–1.17) for sulfate, and 1.05 (95% CI 1.04–1.05) for organic carbon. These findings emphasize the significant impact of PM2.5 on CKD mortality and underscore the need for strategies to reduce PM emissions and manage CKD co-morbidities effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last two decades, Thailand has experienced unprecedented levels of fine particulate matter (PM) emissions. PM is composed of liquid droplets and solid particles with diameters of less than 10 μm (PM10) and 2.5 μm (PM2.5) and is mostly derived from combustion reactions1. The major components of PM2.5 include carbonaceous particles such as organic and black carbon, crystal/mineral dust, inorganic sulfate, and sea salt2. Carbonaceous aerosols result from the combustion of vehicles and non-road machinery, burning of wood, coal, fossil fuels, biomass, and industrial emissions, with black carbon being a major by-product of incomplete combustion. Dust is mostly derived from mineral dust particles entering the atmosphere through sandstorms or wind-driven ocean sprays2. Sea salt aerosol is mainly produced by bursting bubbles during whitecap formation in the open-ocean and significantly correlated with the concentrations of secondary inorganic aerosol and secondary organic carbon3. Lastly, sulfate is derived from fossil fuel combustion and emissions from electrical plants, which release sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere and react with water vapor and other gases to form secondary sulfate aerosols2. This differentiation is critical as the toxicity of PM2.5 is source dependent. Diesel exhaust particles exert the highest levels of oxidative stress, genotoxicity, and oxidative potential, while biomass burning particles show higher levels of inflammatory response and toxicity on cell viability4. Numerous studies provide supportive evidence on the adverse effects of fine PM particles. By penetrating through the alveolar walls and entering the systemic vasculature, they induce increased oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and vascular dysfunction in several organs5,6,7. The choice to focus on the above-mentioned aerosol components derives from their abundant presence within PM2.5 particles, as well as their previous associations with chronic pathologies such as lung cancer8, colon cancer9, scleroderma10, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)11, as well as mortalities from cardiovascular, respiratory, and cerebrovascular diseases (CVD) in the Thai population.

Kidneys are highly vascularized organs, and the accumulation of PM may induce ischemic 'insults' to the microvasculature and promote chronic tubular damage, glomerulosclerosis, intraglomerular hypertension, and tubulointerstitial damage, leading to the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD)12. CKD has emerged as a major health problem in Thailand, with a reported national prevalence of 17.5%. The low socio-economic rural regions of northeastern Thailand are the most affected areas (22.2–26.8%), where CKD causes high hospitalization rates and poses a significant burden on the healthcare system and the economy13,14,15. Several epidemiological studies support an association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and incident CKD, reduction of glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and progression of CKD to end-stage kidney disease7,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. However, limited evidence is available on the effects of PM2.5 and its components on CKD mortality25. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate and characterize the relationship between aerosol concentration, component exposure, and CKD mortality among the 77 Thai provinces. The study aims to identify any specific regional variations likely connected to seasonal emissions and the PM-component-dependent toxicity.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

A total of 718,686 adult CKD patients who died during the 10 year study period were included, accounting for an average 10 year mortality rate of 1,107.33 ± 314.77 cases per 100,000 population. The median age was 72.44 ± 13.10 years, and 50.46% (362,650) of the patients were male. Table 1 presents characteristics of underlying diseases, comorbidities associated with CKD and PM2.5, complications, and renal replacement therapy in the primary- and secondary CKD mortality groups.

The secondary CKD mortality group was older, had a higher proportion of males, and experienced longer hospital stays. Hypertension (HT) and glomerular diseases were predominantly found in the primary CKD mortality group. In contrast, diabetes mellitus (DM), renal stones, gouty nephropathy, tubulointerstitial diseases, and related comorbidities had a higher prevalence in the secondary CKD mortality group. Complications associated with CKD, such as volume overload, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and the percentage of renal replacement therapy, were more frequently observed in patients with primary CKD mortality.

CKD mortality distribution across 77 provinces

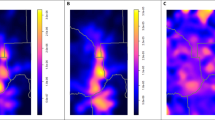

Figure 1A shows the distribution of mortality among the 77 Thai provinces, with the Northeastern region displayed highest mortality rate over 10 years (1,381.27 ± 230.86 cases per 100,000 population, as shown in Supplementary Table S1). Significant mortality was also noted in some provinces in the Northern and Central parts of Thailand. Figure 1B, presents the mortality distribution of the study population subgroups stratified by associated underlying diseases or co-morbidities, i.e., DM, HT, ischemic heart disease (IHD), and CVD. The mortality distribution of the DM and HT subgroups closely corresponded to the total CKD mortality, with Northeastern Thailand highlighted as a hotspot, as demonstrated by R-values of DM 0.78 and HT 0.88 (both p values < 0.01). The IHD and CVD subgroups also significantly correlated with total CKD mortality but to a lesser degree, as represented by the respective R-values of 0.26 (p value = 0.01) and 0.51 (p value < 0.01). Regarding regions of Thailand, the highest mortality was reported as follows: total CKD cases in the Northeastern region, CKD with DM in the Northeastern region, CKD with HT in the Northern region, and CKD with IHD and CKD with CVD in the Central region.

(A) Mortality rate per 10 years of total CKD patients (B) Mortality rate per 10 years of CKD patients were sub-grouped with co-morbidities, i.e., diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and ischemic heart disease (events/100,000 persons of population) during 2012–2021 and distributed by province.

Spatial–temporal analysis of PM2.5 and its component distribution

The distribution of PM2.5 and aerosol components for the 77 Thai provinces is shown in Fig. 2, representing the average annual concentrations for the 10 year study period. Table S2–S5 and Fig. 3 presents the monthly- and seasonal variations of PM2.5 levels and its components, and Table 2 and Figure S2 demonstrate the aerosol concentrations and distribution of PM2.5 component percentages across the six different regions of Thailand and Bangkok metropolitan region. The results displayed high concentration and distribution of PM2.5 in Northern, Northeastern, Central and Bangkok regions. Organic carbon was most densely concentrated in the Northern regions, with more sporadic yet high concentrations in the Northeast and around Bangkok. Dust and sulfate had the highest concentration in the Northern and Northeastern provinces respectively. Black carbon was mostly concentrated in Bangkok and adjacent provinces with moderately high concentration in the Northeast. Sea salt was predominantly found in the Southern, Eastern, and Western regions.

Time series effect of PM2.5 and its components on CKD mortality

As demonstrated in Tables S3 and S4, total PM2.5, black carbon, and organic carbon concentrations were highest from January to April, dust concentrations peaked from March to May, sulfate levels were highest from December to March, and sea salt concentrations were highest from April to July. Figure 3 shows the distribution of aerosol component proportions with seasonal variation: black carbon was predominant from September to January, sulfate from September to February, organic carbon from January to April, dust from April to August, and sea salt from May to September. Similarly, mortality rates for both total CKD cases and primary CKD deaths progressively rose from March, reaching their maximum rates in September each year (Table S3).

A conditional Poisson regression was conducted to determine the effect of monthly PM2.5 exposure on total participants residing in 77 provinces over the 10 year study period. The analysis revealed that every 1 ug/m3 increase in monthly PM2.5, black carbon, sulfate, dust, and organic carbon significantly enhanced CKD mortality (all p values < 0.001). The incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.01 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.01), 1.19 (95% CI 1.19–1.20), 1.17 (95% CI 1.17–1.17), 1.05 (95% CI 1.05–1.06), and 1.02 (95% CI 1.02–1.02), respectively (Table S6 displays IRRs for every 1 and 10 ug/m3 of aerosols). There was no observed effect of sea salt on CKD mortality enhancement.

Impacts of PM2.5 and its components on CKD mortality across the country

Table S7 presents the results of univariate Poisson regression analysis conducted over a 10-year period among 77 Thai provinces to assess mortality risks for each independent variable. Factors significantly associated with increased CKD mortality incidence included PM2.5, organic carbon, dust, sulfate, male sex, increasing age, underlying diseases, comorbidities, CKD stage progression, CKD-related complications, and peritoneal dialysis. Univariate analysis also explored CKD mortality risk between PM2.5 and individual aerosol components among CKD patients with major underlying diseases or comorbidities (Table S8). Significant factors identified in univariate analysis were adjusted as confounders in multivariate Poisson regression analyses to demonstrate PM2.5 and components' impact on mortality rates in CKD patients across the 77 provinces from 2012 to 2021 (Table 3). The incidence rate ratio (IRR) for CKD mortality was represented in the 10-year study period. A 1 µg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentration was significantly associated with an IRR of 1.035 (95% CI 1.033–1.037). Similarly, a 1 µg/m3 increment in black carbon, dust, sulfate, and organic carbon was positively associated with increased CKD mortality, with IRRs of 1.114 (95% CI 1.103–1.125), 1.237 (95% CI 1.224–1.249), 1.162 (95% CI 1.156–1.169), and 1.046 (95% CI 1.043–1.048), respectively. The appropriateness of the multivariate statistical model was confirmed by R2 values ranging from 0.80 to 0.84. Additionally, a 1 µg/m3 increase in PM2.5 and all aerosol components, except sea salt, was significantly associated with increased mortality in CKD. Patients with underlying or comorbid conditions of DM, HT, IHD, CVD, and lung cancer (Table S9).

Apart from the impact of PM2.5, increasing age, male sex, and comorbidities including DM, IHD, renal stones, hyperlipidemia, COPD, asthma, lung cancer, complications of anemia and metabolic acidosis, as well as peritoneal dialysis, were significantly associated with CKD mortality (Table S10). Additionally, in the multivariable Poisson analysis considering the interaction effect of all five components together, sulfate exhibited the strongest association with CKD mortality.

Aerosol components' impact on CKD mortality by R-INLA

The multivariate Poisson log-linear model, adjusted for age, sex, income, length of hospital stays at the last visit, underlying diseases, comorbidities, CKD-related complications, renal replacement therapy, and population density, confirmed the risk of PM2.5 and aerosols on total CKD mortality, in line with the multivariable Poisson regression analysis. Every increase of 1 μg/m3 in PM2.5, organic carbon, black carbon, dust, and sulfate was associated with a 3.6%, 4.0%, 15%, 17.9%, and 9.3% increase in CKD mortality, respectively, across the 77 provinces (Table 4).

Aerosol concentrations in each CKD stage

Comparisons of PM2.5 and its component concentrations among the five CKD stages revealed significant differences (all p values < 0.001) which showed greater levels in higher stage, except the sea salt, especially pronounced in CKD stage 3–5 (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study unveiled high CKD mortalities and greater annual PM2.5 concentrations than recommended levels in Thailand during the 2012–2021 period. The Northeastern and Northern regions were identified as hotspots for CKD mortality, correlating with high concentrations of PM2.5, dust, sulfate, and organic carbon, while black carbon was predominantly found in the central part and some areas of the northeastern regions. All statistical models—conditional Poisson, multivariate Poisson regression analysis, and R-INLA—consistently demonstrated that increasing PM2.5 and components (excluding sea salt) were associated with a heightened risk of CKD mortality and greater concentrations of aerosols in higher CKD stages. Multivariate Poisson analysis further supported the impacts of PM2.5 and its components on subgroups of primary- and secondary CKD mortalities, as well as CKD with major comorbidities. Globally, studies have highlighted a link between PM2.5 exposure and CKD incidence, progression and mortality20,21,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. A recent systematic review indicated that for every 10 μg/m3 increase in long-term exposure to PM2.5 there is an elevated risk of CKD incidence (adjusted OR 1.31) and prevalence (adjusted OR 1.31) particularly in the Asian region32.

Literature on PM2.5 and CKD mortality remains limited. A 6.14 year cohort study from Korea reported a 1.17 times higher mortality risk associated with PM2.5 exposure in CKD patients25. Another retrospective cohort study found that prolonged PM2.5 exposure increased mortality hazard ratios by 1.97 and 1.42 per IQR increase (4.0 µg/m3) among elderly CKD patients with IHD and HT, respectively33. Comorbidities such as DM and HT are also affected by PM 2.5 exposure and can both exacerbate symptoms and drive CKD progression32. The findings of the current study align with previous research, indicating that every increase in PM2.5 by 1 µg/m3 is associated with 1.035 times rise in total CKD mortality, equivalent to an incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.41 for every 10 µg/m3 increment of PM2.5.

Nowadays, information regarding the impact of PM2.5 components on CKD is lacking. Zhang et al. reported that CKD prevalence in China was highly related to the increment of the previous 1-year average PM2.5 exposures and levels of ammonium, black carbon, nitrate, sulfate, and organic material, with sulfate contributing the most among these five components of PM2.534. This present study is the first to identify the impact of PM2.5 components, namely black carbon, dust, sulfate, and organic carbon, on CKD mortality, with sulfate demonstrating the highest association. These four agents are major components of PM2.5, which has been recognized for its human toxicity35. Furthermore, sulfate is one of the secondary PM2.5 aerosols resulting from the chemical reaction of gaseous particles and can further combine with other substances, enhancing mortality, cardiopulmonary, ischemic heart, and pulmonary diseases36. Current research suggests that black carbon, an ultrafine PM2.5 fraction, oxidizes plasma proteins and transports other harmful combustion-related chemicals, impacting immune cells and systemic circulation37. Biopsy studies have identified black carbon around blood vessels, glomeruli, and peritubular capillary walls, linking its accumulation to adverse kidney outcomes38. Additionally, other studies have linked black carbon, dust, and PM2.5 exposure to increased mortality from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases39,40,41,42.

Increasing air pollution trends are associated with rapid population growth, economic development, industrialization, and urbanization. Developing countries face significant impacts and geographical variations due to diverse emission sources43. The distribution of components across Thailand exhibits significant regional and seasonal variations (Fig. 2 and S2, Table 3, S3, and S4). The highest concentrations of dust, organic, and black carbon PM2.5 are observed between January and April, reflecting the haze periods in Northern and Northeastern Thailand caused by forest fires, biomass, and crop-residue burning. A study from Chiang Mai identified biomass burning and cross-border pollution as the main dry-season sources, and exhaust dust and traffic emissions as the main wet-season sources44. High sulfate concentrations in the Northeastern and Central regions likely stem from electrical plants and industrial zones. Southern Thailand experiences biomass combustion and maritime aerosol emissions from June to October. The Central regions and Bangkok metropolitan area primarily face emissions from vehicles, industry, secondary aerosols, and biomass burning45. This diversity of PM sources, combined with a high incidence of comorbidities and traditional and non-traditional risk factors such as hotter climate, agrochemical exposure, and poverty, might explain the high mortality rate in Thailand, especially in the Northeastern region.

Since 2012, the AQI app has provided real-time pollution data, helping citizens make informed exposure decisions. In 2021, the WHO lowered global average annual emission standards for PM2.5 from 10 to 5 µg/m3 due to an increasingly significant body of evidence linking PM emission to chronic and non-communicable diseases46. Thailand's National Environmental Board responded by announcing that, starting June 1, 2023, the country's thresholds would be reduced from 50 to 37.5 μg/m3 daily and from 25 to 15 μg/m3 annually47. While still higher than WHO guidelines, this marks progress in addressing air pollution's public health impact. However, the present study reveals consistent annual concentrations above 15 µg/m3, with the highest concentration registered in 2013 (19.15 µg/m3) and the lowest in 2017 (14.99 µg/m3). Despite the increased awareness and current intervention strategies to prevent and control PM emissions, significant challenges remain; Amongst them, the difficulty to enforce restrictions on biomass burning in rural and mountainous areas and the management of cross-border pollution persists45. A better characterization of aerosol components and risk factors involved in PM induced illnesses and respective distribution is crucial for effective public health policies. That, in addition to a multidisciplinary approach, involving environmental, agricultural, medical, and economic experts, is essential to prevent, manage and control PM-induced illnesses like chronic kidney disease (CKD).

This study has the following limitations: (a) detailed data on the differentiation of PM component distribution within each province were not available for extraction through the NASA Giovanni satellite; (b) confounding variables such as education, lifestyle factors, smoking status, contact of indoor air pollution, employment sector, and assumptions of prescription drugs cannot be accounted for within the current research design; (c) the study only analyzed data obtained from the National Health Security Office (NHSO) covering approximately 75% of the Thai population which demographic and health profiles may differ in uncovered groups, therefore, reducing generalizability of the findings to the whole Thai population; (d) NASA Giovanni database cannot differentiate between urban and rural areas variability in PM2.5 exposure estimates reducing geographic generalizability of results. Further studies to analyze the source apportionment to predict proportions of each source emission origin and its potential impact, and also the influence of meteorology parameters such as temperature, humidity and wind rates on PM2.5 concentrations are warrant.

The study has some strengths as follows; (a) analyzing 10 years of CKD hospitalization and mortality data and aerosol concentrations; (b) employing spatial–temporal analysis (association between location of hospitalization and aerosol components); satellite models provide a national estimation of PM2.5 ground concentrations, even though clouds and bright surface reflections may occasionally result in missing values; (c) The study included major underlying diseases and comorbidities associated with CKD, and (d) it investigated and differentiated between five major aerosol components and their individual distribution in association with CKD mortality.

Conclusion

The presented data show that increasing concentrations of PM2.5, dust, sulfate, organic and black carbon magnify CKD mortality. Age, male sex, secondary CKD diagnosis, comorbidities further increase the risk of mortality. Northeastern Thailand appears to be the most significantly affected region, likely due to the high incidence of comorbidities strongly associated with CKD, such as DM and HT, as well as the synergistic toxic effects of PM2.5 and different aerosol components. Further research, accounting for non-traditional risk factors and confounding variables, is needed to better understand the relationship between increasing aerosol concentration and CKD development, progression, and mortality.

Methods

Study design and population

The study investigated the spatial and temporal relationships and relative risks of exposure to aerosol components for mortality in CKD patients identified under code N18 of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10). The objective of this study was to assess the effect of PM2.5 components on CKD mortality across the 77 provinces of Thailand during a 10-year study period (2012 to 2021). The study was designed to identify the geographic distribution of provinces (spatial analysis) and the changing concentration of PM2.5 and its component and mortality rate over time in these regions (temporal analysis).

Data collection and variable definition

The in-patient medical forms of CKD patients from fiscal years 2012–2021 were obtained from the NHSO, the main Thai health scheme covering approximately 75% of the total Thai population. The data were analyzed to investigate the association between the magnitude and components of PM2.5 and mortality in terms of spatial and temporal relationships. The data were first checked for accuracy by examining overlapping information, visit dates, missing items, incorrect coding, and correct fiscal year assignment. CKD patients were identified by physicians as primary or secondary diagnoses under code N18 of ICD-10 which defines CKD based on the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria as the persisting presence of either one or more parameters of renal damage or reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for longer 3 months48. The study included individuals aged ≥ 18 years who passed away either within or outside local hospitals recorded in the Thai census by the National Statistical Office during 2012–2021. The collected data for deceased CKD patients who had been hospitalized included age, sex, hospital province address, underlying diseases, co-morbidities, CKD stage 1–5 defined as KDIGO48, complications, and mode of dialysis. Underlying diseases and co-morbidities associated with mortality in CKD and/or PM2.5 exposure and their ICD-10 codes were diabetes mellitus (DM, E08-E14), hypertensive disease (HT, I10-I16), renal stone (N20-N21), glomerular diseases (N00-N08, M32.1), gout (M10), tubulointerstitial disease (N10-N16), ischemic heart disease (IHD, I20-I25), heart failure (I50), cerebrovascular disease (CVD, I60-I69), hyperlipidemia (E78), pneumonia (J12-J18), sepsis (A40-A41), diarrhea (A09), acute kidney injury (N17), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, J43-J44), asthma (J45), and lung cancer (C34). The focused CKD complications were anemia (ICD-10: A63.8, D64.9), volume overload (E87.7, J81), hyperkalemia (E87.5), and metabolic acidosis (E87.2). Dialysis modes were identified as hemodialysis (ICD-10: Z49.1) and peritoneal dialysis (ICD-10: Z49.2). The study cases were counted and distributed among the 77 provinces, and the incidence rates of CKD mortality were presented as events per 100,000 persons of the mean population during the 10 year study period for each province. Census data of the Thai population were obtained from https://www.healthdata.org/thailand49.

Spatial and temporal resources

Spatial resources were determined using the Geographical Information System (GIS), with longitudes ranging from 97.96852 to 105.22908 and latitudes ranging from 5.77434 to 20.433537. Data on area and population density for all 77 provinces in Thailand were included. Aerosol components and PM2.5 concentration data were assessed using The Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Application version 2 (MERRA-2), a NASA atmospheric satellite model (M2TMNXFLX v5.12.4) with a horizontal resolution of 0.5 × 0.625, approximately 50 km. Temporal resolution was monthly, and exposure estimates were assigned based on provincial hospitalization address50. The Aerosol Diagnostics Model was used to identify the chemical type of each aerosol component and its monthly surface mass concentration. These components included black carbon, organic carbon, dust, sulfate, and sea salt. Additionally, the monthly mean levels of each aerosol component during the 10-year study period were determined and represented using geophysical parameters in both vertical and horizontal grids, based on Giovanni's data product between 2012 and 2021. Platforms like NASA's Giovanni (https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov/giovanni/) provide user-friendly access to satellite data, empowering researchers to address air quality challenges through PM2.5 component analysis. The application of MERRA-2 has seen success in several previous studies like those by Xu et al., Yousefi et al., and Soleimanpour M. et al., employing the method to determine population exposure, PM trends, and seasonal variations respectively51,52,53. PM2.5 surface concentration was determined by summing aerosol components using the following formula suggested by Buchard et al.54: PM2.5 = DUSMASS25 + OCSMASS + BCSMASS + SSSMASS25 + SO4SMASS * (132.14/96.06).

Outcome measures

The parameters of interest included the number, age, and sex of deceased CKD patients during the 10-year study period; the spatial distributions of CKD mortality, underlying diseases, co-morbidities related to CKD, PM2.5 and aerosol components; and the risk of CKD mortality according to PM2.5 and its component adjusted for related underlying disease and co-morbidities. The total CKD mortality was divided into 2 subgroups, i.e., primary CKD mortality defined as the mortality in participants who were diagnosed with CKD as the primary diagnosis, and secondary CKD mortality in those whom their CKD was the secondary diagnosis. The 10 year distribution of mortality rates and average annual aerosol components among the 77 provinces were displayed on a map of Thailand using QGIS software version 3.8.2, an open-source and free software for geographic data information systems55.

Statistical analyses

Data were categorized into dichotomous, polytomous categorical variables, or continuous variables. Categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages, while continuous data were presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate. To define the distribution of CKD mortality (N18), the addresses from hospitalization data were mapped using spatial data analyses based on latitude and longitude. Means difference between the two groups were compared by using the Student’s t-test for independent variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for comparison of means among more than two groups. Comparisons of categorical variables between groups was analyzed by Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test. Correlations between the distribution of CKD mortality and co-morbidities in various Thai regions were determined and presented as R-values. The conditional Poisson regression, using a time-stratified case-crossover design equivalent to the time series methods in environmental epidemiology as suggested by Lu and Zeger SL56, was performed to determine the effect of monthly PM2.5 exposure in total participants stratified into groups of 120 months with 77 provinces over the 10-year study period. Poisson regression analysis was conducted to examine factors potentially associated with CKD mortality across the 77 Thai provinces over the 10-year study period. Considered factors included mean levels (for continuous variables) and counts (for categorical variables) of total PM2.5 levels, each aerosol component type, age, sex, underlying diseases, comorbidities related to CKD and PM2.5, CKD stage, complications, mode of renal replacement therapy, provincial income, healthcare levels (indicating urban and rural populations), and population density, all treated as independent variables. The IRR and its 95% CI were calculated to identify factors related to mortality in different provinces of Thailand, with provinces having low incidence rates serving as a reference for estimating high-risk areas. IRRs showing effects in univariable analysis with a p value < 0.05 were included in a multivariate Poisson regression model to explore the associated effects of PM2.5 and each aerosol component on total CKD, primary CKD, and secondary CKD mortalities after adjustment for confounders. Additionally, Bayesian inference for spatial–temporal data was performed using the R-Package Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (R-INLA) to confirm the effects of PM2.5 and each aerosol component on CKD mortality, integrating related variables as described in the multiple Poisson regression model. Data analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software version 17.0 and program R version 3.6.1 (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained following an assessment by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University (COA no. HE 601166 and HE621357), in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. The need for informed consent was considered unnecessary by the Khon Kaen University Human Research Committee. The data were obtained from a public domain database for non-commercial purposes and were made anonymous to ensure confidentiality.

Data availability

The datasets generated in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Niampradit, S. et al. The elemental characteristics and human health risk of PM2.5 during Haze Episode and Non-Haze Episode in Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(10), 6127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106127 (2022).

Voiland, A. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Aerosols: tiny particles, big impact. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/ features/Aerosols. (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Chemical compositions and the impact of sea salt in atmospheric PM1 and PM25 in the coastal area. Atmospheric Res. 250, 105323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2020.105323 (2021).

Park, M. et al. Differential toxicities of fine particulate matters from various sources. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 17007. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35398-0 (2018).

Al-Aly, Z. & Bowe, B. The road ahead for research on air pollution and kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32(2), 260–262. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020121713 (2021).

Blum, M. F. et al. Particulate matter and albuminuria, glomerular filtration rate, and incident CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 15(3), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.08350719 (2020).

Bowe, B. et al. The global and national burden of chronic kidney disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter air pollution: A modelling study. BMJ Glob Health 5(3), e002063. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002063 (2020).

Jenwitheesuk, K., Peansukwech, U. & Jenwitheesuk, K. Construction of polluted aerosol in accumulation that affects the incidence of lung cancer. Heliyon 6(2), e03337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03337 (2020).

Jenwitheesuk, K., Peansukwech, U. & Jenwitheesuk, K. Accumulated ambient air pollution and colon cancer incidence in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 17765. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74669 (2020).

Foocharoen, C., Peansukwech, U., Pongkulkiat, P., Mahakkanukrauh, A. & Suwannaroj, S. Aerosol components associated with hospital mortality in systemic sclerosis: An analysis from a nationwide Thailand healthcare database. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 7983. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87114-0 (2021).

So-Ngern, A. et al. Dust and organic carbon in ambient air pollution associated with increased mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in Thailand. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 104, 63–70 (2021).

Yang, Y. R., Chen, Y. M., Chen, S. Y. & Chan, C. C. Associations between long-term particulate matter exposure and adult renal function in the Taipei Metropolis. Environ. Health Perspect. 125(4), 602–607. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP302 (2017).

Ingsathit, A. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic kidney disease in the Thai adult population: Thai SEEK study. Nephrol Dial Trans. 25(5), 1567–1575. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfp669 (2010).

Cha’on, U. et al. CKDNET, a quality improvement project for prevention and reduction of chronic kidney disease in the Northeast Thailand. BMC Public Health 20(1), 1299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09387-w (2020).

Anutrakulchai, S. et al. Mortality and treatment costs of hospitalized chronic kidney disease patients between the three major health insurance schemes in Thailand. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16(1), 528. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1792-9 (2016).

Seo-Yun, H. et al. Association of air pollutants with incident chronic kidney disease in a nationally representative cohort of Korean adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(7), 3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073775 (2021).

Ye, J. J., Wang, S. S., Fang, Y., Zhang, X. J. & Hu, C. Y. Ambient air pollution exposure and risk of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 195, 110867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.110867 (2021).

Aekplakorn, W. et al. Women and other risk factors for chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Thailand: National Health Examination V Survey. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 21366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00694-9 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Associations between long-term exposure to low-level air pollution and risk of chronic kidney disease-findings from the Malmö Diet and Cancer cohort. Environ. Int. 160, 107085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107085 (2022).

Mehta, A. J. et al. Long-Term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and renal function in older men: The veterans administration normative aging study. Environ. Health Perspect. 124(9), 1353–1360. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1510269 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Liu, D. & Liu, Z. Fine particulate matter (pm2.5) and chronic kidney disease. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 254, 183–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/398_2020_62 (2021).

Chen, S. Y., Chu, D. C., Lee, J. H., Yang, Y. R. & Chan, C. C. Traffic-related air pollution associated with chronic kidney disease among elderly residents in Taipei City. Environ. Poll. 234, 838–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.084 (2018).

Lin, Y. T. et al. Particulate air pollution and progression to kidney failure with replacement therapy: an advanced CKD registry-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76(5), 645–657. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.02.447 (2020).

Bowe, B. et al. Particulate matter air pollution and the risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 29(1), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2017030253 (2018).

Jung, J. et al. Effects of air pollution on mortality of patients with chronic kidney disease: A large observational cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 786, 147471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147471 (2021).

Ke, C., Liang, J., Liu, M., Liu, S. & Wang, C. Burden of chronic kidney disease and its risk-attributable burden in 137 low-and middle-income countries, 1990–2019: Results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Nephrol 23(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-021-02597-3 (2022).

Okoye, O. C., Carnegie, E. & Mora, L. Air pollution and chronic kidney disease risk in oil and gas- situated communities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health 67, 1604522. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604522 (2022).

Xu, X. et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and increased risk of membranous nephropathy in China. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 27(12), 3739–3746. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016010093 (2016).

Li, G. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 and increased risk of CKD prevalence in China. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32(2), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020040517 (2021).

He, D. et al. Association between particulate matter 2.5 and diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Diabetes Investig. 8(5), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12631 (2017).

Pope, C. A. et al. Relationships between fine particulate air pollution, cardiometabolic disorders, and cardiovascular mortality. Circ. Res. 116(1), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305060 (2015).

Wathanavasin, W., Banjongjit, A., Phannajit, J., Eiam-Ong, S. & Susantitaphong, P. Association of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure and chronic kidney disease outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1048. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51554-1 (2024).

Ran, J. et al. Fine particulate matter and cause-specific mortality in the Hong Kong elder patients with chronic kidney disease. Chemosphere 247, 125913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.125913 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Association of the components of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and chronic kidney disease prevalence in China. J. Environ. Manage 339, 117885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117885 (2023).

Thangavel, P., Park, D. & Lee, Y. C. Recent insights into particulate matter (PM2.5)-mediated toxicity in humans: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(12), 7511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127511 (2022).

Mangia, C., Cervino, M. & Gianicolo, E. A. Secondary particulate matter originating from an industrial source and its impact on population health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12(7), 7667–7681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120707667 (2015).

Sørensen, M. et al. Personal PM2.5 exposure and markers of oxidative stress in blood. Environ. Health Perspect 111(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.111-1241344 (2003).

Rasking, P. et al. Black carbon reaches the kidneys. Toxicol. Lett. 368, S166–S167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2022.07.461 (2022).

Li, Y., Zheng, C., An, X. & Hou, Q. Acute effects of black carbon on mortality in nine megacities of China, 2008–2016: A time-stratified case-crossover study. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. Int. 29(38), 57873–57884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19899-0 (2022).

Rahmatinia, M. et al. Relationship between ambient black carbon and daily mortality in Tehran, Iran: a distributed lag nonlinear time series analysis. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40201-021-00659-0 (2021).

Stafoggia, M. et al. Long-term exposure to low ambient air pollution concentrations and mortality among 28 million people: Results from seven large European cohorts within the ELAPSE project. Lancet Planet Health 6(1), e9–e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00277-1 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Long-term exposure to PM25 major components and mortality in the southeastern United States. Environ. Int. 158, 106969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106969 (2022).

Soleimanpour, M., Alizadeh, O. & Sabetghadam, S. Analysis of diurnal to seasonal variations and trends in air pollution potential in an urban area. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 21065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48420-x (2023).

Chansuebri, S. et al. Chemical composition and origins of PM2.5 in Chiang Mai (Thailand) by integrated source apportionment and potential source areas. Atmos. Environ. 327, 120517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120517 (2023).

Suriyawong, P. et al. Airborne particulate matter from biomass burning in Thailand: Recent issues, challenges, and options. Heliyon 9(3), e14261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14261 (2023).

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. ISBN 9789240034228 (electronic version). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/ 345329. (2021).

Johjit, K. & Angskul, T. Thailand to Tighten Air Quality Safety Standards. https://thainews.prd.go.th/en/news/detail/TCATG220715124733629. (2022).

KDIGO CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 3, 1–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2012.73 (2013).

Health data Thailand 2023. https://www.healthdata.org/thailand (2023).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1 (2017).

Xu, Y., Wu, J. & Han, Z. Evaluation and projection of surface PM2.5 and its exposure on population in Asia based on the CMIP6 GCMs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19(19), 12092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912092 (2022).

Yousefi, R. et al. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) trends from land surface changes and air pollution policies in China during 1980–2020. J. Environ. Manage. 326(Pt B), 116847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116847 (2023).

Soleimanpour, M., Alizadeh, O. & Sabetghadam, S. Analysis of diurnal to seasonal variations and trends in air pollution potential in an urban area. Sci.. Rep. 13(1), 21065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48420-x (2023).

Buchard, V. et al. The MERRA-2 aerosol reanalysis, 1980 Onward. Part II: Evaluation and case studies. J. Clim. 30(17), 6851–6872. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-16-0613.1 (2017).

QGIS 3.8.2. https://timdocs.qgis.org/en/site/forusers/download.html (2019).

Lu, Y. & Zeger, S. L. On the equivalence of case-crossover and time series methods in environmental epidemiology. Biostatistics 8(2), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxl013 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Health Security Office of Thailand (NHSO) for provision of study population data, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to distribute opensource information of satellite-derived aerosol concentration and components, and Professor Sumitra Thongprasert for providing the health data. AL was supported by a Postgraduate Study Support Grant of Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University for her PhD study.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Fund of Khon Kaen University (FF66) which received funding from The National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), Thailand. The funders have no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L., U.P., J.C., U.C., S.S., and S.A. conceived and designed the research project. A.L., U.P., and S.A. carried out the data acquisition. A.L., U.P., J.C., U.C., S.S. and S.A. interpreted the results. A.L., U.P. and S.A. performed the statistics. A.L., U.P., S.S., and S.A. drafted the manuscript. All the authors provided critical feedback, commented on the manuscript and agreed to the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leonetti, A., Peansukwech, U., Charnnarong, J. et al. Effects of particulate matter (PM2.5) concentration and components on mortality in chronic kidney disease patients: a nationwide spatial–temporal analysis. Sci Rep 14, 16810 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67642-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67642-1