Abstract

To develop the Head and Neck Cancer Psychosocial Distress Scale (HNCPDS) with the aim of identifying high-risk individuals for psychosocial distress among patients, and to assess its reliability, validity and applicability. Using the classical test theory, a total of 435 head and neck cancer patients from six tertiary hospitals in China were recruited for developing the HNCPDS. Delphi expert consultation and item analysis were used to improve the content validity of the preliminary HNCPDS. Factor analysis (FA) and Structural equation modeling (SEM) were used to test the structural validity of HNCPDS. Cronbach's alpha coefficient, Spearman-Brown coefficient and Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) were used to test the internal consistency and retest reliability of HNCPDS. Multiple stepped-linear regression was used to analyze the risk factors of psychological disorder, and Pearson correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between psychosocial distress and quality of life (QOL). The HNCPDS consisted of 14 items, which were divided into 3 subscales: 3 items for cancer discrimination, 5 items for anxiety and depression, and 6 items for social phobia. The HNCPDS had good validity [KMO coefficient was 0.947, Bartlett’s test was 5027.496 (P < 0.001), Cumulative variance contribution rate was 75.416%, and all factor loadings were greater than 0.55], reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.954, Spearman-Brown coefficient was 0.955, test–retest reliability was 0.845) and acceptability [average completion time (14.31 ± 2.354 min) and effective completion rate of 90.63%]. Financial burden, sex, age and personality were found to be independent risk factors for HNCPDS (P < 0.05), and patients with higher HNCPDS scores reported a lower QOL (P < 0.01). The HNCPDS is effective and reliable in early identification and assessment of the level of psychosocial distress in patients with head and neck cancer, which can provide an effective basis for health education, psychological counseling, and social support in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, the incidence and mortality of cancer have continued to increase globally1. Data from the National Cancer Center of China in 2024 showed that the number of new head and neck cancer (including thyroid cancer, oral cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer and laryngeal cancer, etc.) cases and deaths reached 612,000 and 92,000 respectively, which had ranked first globally2. This has become a significant threat to public physical and mental health, as well as social and economic development.

With the development of medicine, although the efficacy and prognosis of cancer treatment have continuously improved, due to the lack of attention to social and psychological support in the past, the mental health problems of cancer patients are increasing3,4. “Psychosocial distress” refer to a variety of psychological, personality and behavioral abnormalities caused by physiological, psychological and social factors, which includes discrimination, anxiety, depression, emotional distress, and fear5. The pressure from cancer fear, treatment toxicity, risk of long-term recurrence and progression, and social incomprehension are often the main reasons for patients' negative psychology, and eventually lead to varying degrees of psychosocial distress in patients6,7. Profound and lasting psychological damage not only prevents patients from actively cooperating with treatment and seeking psychological counseling services, but also seriously reduces the QOL of patients, and even increases the risk of suicide death of patients8,9. In addition, recent studies have found that negative psychology is an independent risk factor for evaluating the efficacy, prognosis and QOL of cancer patients, and have gradually become a new focus of attention in the comprehensive treatment and whole-process management of cancer10. However, studies on disease-related psychosocial distress among head and neck cancer patients are relatively simple or one-sided, especially in China.

Previous studies have shown that the psychosocial distress of cancer patients may stem from cancer discrimination, stigma, anxiety, depression, and social phobia. Because of the “cancer peculiar horror”, the public always looks at cancer patients with "colored glasses" and consciously reduces communication with them, and even stigmatize patients with head and neck cancer11. The therapeutic toxicity of disfigurement often makes it difficult for cancer patients to adapt in a short period of time, which leads to their inferiority and anxiety, especially in postoperative patients with head and neck cancer12. However, poor appearance makes cancer patients more susceptible to rejection and disdain from others, which may lead to social phobia13. In addition, the emotions experienced by relatives and friends changed from initial concerns to final indifference, and even the abandonment of the head and neck cancer patients for fear of their own safety was threatened14.

At present, there is currently no suitable instrument for assessing the level of psychosocial distress among head and neck cancer patients. Although there were several anxiety and depression related assessment scales (including HADS, GAD-7, PHQ-9, BDI-II)15,16,17,18, in the past, these scales were mostly used to measure psychological disorders in non-cancer populations, while none of them were specifically used to evaluate cancer patients, especially those with head and neck cancer. Furthermore, although our previously developed Thyroid Cancer Self-Perceived Discrimination Scale (TCSPDS) could be used to preliminarily estimate the self-perceived discrimination of thyroid cancer patients, it is still an aspect of psychosocial distress and had limited applicability to other head and neck cancer patients19. In addition, while Cataldo JK's Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale (CLCSS), adapted from the HIV Stigma Scale, and DW Kissane's Shame and Stigma Scale (SSS) were effective for specific types of cancer, they specifically address the shame and stigma related to changes in body image20,21. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a more comprehensive and universal psychosocial distress scale to systematically measure the level of psychological health in patients with head and neck cancer, including discrimination, anxiety and depression, and social phobia.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to develop and validate a specific Head and Neck Cancer Psychosocial Distress Scale (HNCPDS) to identify patients at high risk for psychosocial distress, analyze the correlation between psychosocial distress and QOL, and conduct relevant interventions targeting risk factors to improve patients' physical and mental health and QOL.

Methods

Participants

Patients with head and neck cancer treated at six tertiary hospitals (The First Hospital of Nanchang, Yunnan Cancer Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Pingxiang People's Hospital, and Anning First People's Hospital) in China were used as the research subjects. Individuals who were patients from October to December 2022 were selected as the qualitative research (included semi-structured interview and cognitive interview) objects, and those from July 2023 to February 2024 were selected as the questionnaire objects.

The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) had a diagnosis of head and neck cancer (nasopharyngeal carcinoma, oral cancer, thyroid cancer, and laryngeal cancer) according to histopathology (tumor staging following the AJCC Version 8 criteria)22, (2) the duration of cancer was at least 1 month, (3) had good language expression capability and understanding ability, (4) were aware of their diagnosis and volunteered to participate in the study, and (5) were ≥ 18 years old. The exclusion criteria for patients were as follows: had (1) other primary cancers outside the head and neck, or (2) an infectious disease, a mental disorder, a brain trauma history, a physical disability, or a critical illness.

Ethical approval for this multicenter study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University-Yunnan Cancer Hospital (NO. KYLX2022063). We promised the participants that the data would only be used for this study, without any commercial use, and that the participants could withdraw from the study at any time. In addition, we confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Qualitative research

A semi-structured interview was conducted to establish an interview outline by reviewing literature related to the negative psychology of head and neck cancer: (1) How did you feel after being diagnosed with head and neck cancer? (2) Did it affect your work and life after suffering from head and neck cancer? (3) Have you ever been treated unfairly? How did you feel psychologically? (4) Did your relationships change after you had suffered from head and neck cancer? If necessary, the researchers asked additional follow-up questions based on the patients' answers (from October to December 2022).

Independent interviews were conducted in the conference room with the consent of the participants, and each interview lasted approximately 40–50 min. Based on the construction grounded theory, within 24 h after the interview, two researchers independently coded the interview data via NVivo 12 PLUS, and a third researcher made decisions when disagreements occurred. This part of the study followed the principle of the "information saturation method", so the sample size of participants depended on whether further information was available in the interview23.

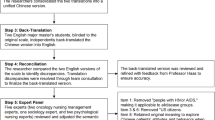

Development of the preliminary HNCPDS

An item pool was established through qualitative research and literature reviews14,19,20,21,24,25,26. The language design (content, grammar, and sentence patterns) should refer to the literature review and conform to Chinese grammar. The items were expressed on a 5-point Likert scale, and all items were forward-scored, the options were as follows: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = not sure, 4 = somewhat agree, and 5 = strongly agree. Therefore, a higher score indicated a greater level of psychological disorder (from January to February 2023).

The Delphi expert consultation method was used to invite experts in oncology, psychology, head and neck surgery, and linguistics to revise and review the content and applicability of each item27. The first round of consultation mainly involved revising the content, grammar, and sentence patterns of each item. In the second round of consultation, a 4-point rating scale (1 = uncorrelation, 2 = weak correlation, 3 = moderate correlation, 4 = strong correlation) was used to independently review each item by experts, and the item-level content validity index (I-CVI) was calculated (from March to April 2023).

A small portion of the patients with head and neck cancer were invited to participate in cognitive interviews on the description, content, and significance of each item to ensure that all items could be easily read, understood, and accepted in the formal investigation (from May to June 2023).

Questionnaire formation and distribution

The questionnaire consisted of four parts: (1) The general information of the participants was designed by the researchers according to the needs, included age, sex, economic burden, education level, and tumor stage. (2) The Simplified version of 10-question Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) personality types was included, which was used to initially determine a patient's personality traits (introvert or extrovert)28. (3) The preliminary HNCPDS was included. (4) The Cancer Self-Perceived Discrimination Scale (CSPDS) was included: it was used to assess the level of self-perceived discrimination in cancer patients, with 14 items covering 3 dimensions (stigma, self-deprecation, and social avoidance), with good reliability and validity (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.829)29. (5) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ⁃C30) was included: it has been widely used to evaluate the QOL of cancer patients. It covered 15 domains with 30 items, including 5 functional domains, 3 symptom domains, 6 single items, and one global health domain, with good reliability and validity, with higher scores indicating lower QOL30.

According to the convenience sampling method, questionnaires were distributed to patients with head and neck cancer who came to the six hospitals mentioned above for treatment and the questionnaires were collected on site. All questionnaires were independently completed by the participants according to their own assumptions, and the completion time of the questionnaire was recorded. To qualify for factor analysis, the ratio between sample and item size was at least 5–10, with an appropriate increase of 20%, and the common recommendation for sample size was N ≥ 20031. The formal investigation was conducted from July 2023 to February 2024.

Validation of HNCPDS

Delphi expert consultation and item analysis were used to improve the content validity of the preliminary HNCPDS and establish the initial theoretical model of the scale27,32. SEM was used to construct the initial theoretical model of the HNCPDS, and the primary model was verified by factor analysis (FA)33. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used for dimensionality reduction in the HNCPDS, and common factors were extracted via principal component analysis (PCA)34. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to analyze the validity coefficient between the HNCPDS, CSPDS and QLQ-C30 to test the criterion-related validity (CRV) of the HNCPDS35. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient, Spearman-Brown coefficient and test–retest reliability were used to verify the reliability of the HNCPDS36. The applicability of the HNCPDS was verified by the effective completion rate and average completion time37.

Application of HNCPDS

One-way ANOVA was used to compare the HNCPDS scores of participants with different baseline characteristics, and multiple stepwise linear regression analysis was used to analyze the independent risk factors for patients with HNCPDS. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between the scores of HNCPDS and QOL.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0, AMOS 24.0 and NVivo 12 PLUS were used for statistical analysis. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Third Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University-Yunnan Cancer Hospital (NO. KYLX2022063). The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 480 patients with head and neck cancer agreed to participate, and 435 patients completed the questionnaire (45 participants with incomplete questionnaires, a history of other primary cancers, or unwillingness to provide informed consent were excluded). Among the 435 participants, 137 were diagnosed with thyroid cancer, 171 with nasopharyngeal cancer, 53 with oral cancer, 36 with throat cancer, and 38 with other head and neck malignancies; 263 were female and 172 were male; 229 were assessed as introverts and 206 as extroverts (Table 1).

Qualitative research

According to the semi-structured interviews, three themes of cancer discrimination, anxiety and depression, and social phobia were extracted from the psychosocial distress of 23 head and neck cancer patients. Cancer discrimination included three subthemes: cancer fear, stereotypes, and stigma. Anxiety and depression included three subthemes: cancer pain, disfigurement dilemmas, and self-deprecation. Social phobia included two subthemes: disease concealment and self-isolation.

Development of the preliminary HNCPDS

Based on qualitative research and literature review, a preliminary HNCPDS with 16 items was developed. We invited a total of 7 experts (2 oncology, 2 psychology, 2 head and neck surgery, and 1 linguistics) for consultation. In the first round of consultation, we revised three items: item 1 “Some people will avoid me because of my wound” was revised to “Some people get scared when they see my wound”, item 4 “Cancer pain has deprived me of confidence and attractiveness” was revised to “Cancer pain has deprived me of my faith”, and item 10 “Sometimes it feels like I'm going to die” was revised to “Sometimes I feel like my life is coming to an end”. In the second round of consultation, excepted for items 15 "Sometimes I feel like a useless person" and 16 "Some people believe that head and neck cancer could be contagious" with I-CVI values of 0.71 and 0.57, respectively, and the I-CVI values of the other items were more than 0.80. Therefore, items 15 and 16 were deleted.

After that, according to the findings of qualitative research and group discussions, the 14-item HNCPDS was developed into an initial theoretical model comprising a tri-dimensional correlation model: cancer discrimination, anxiety and depression, and social phobia. Among them, cancer discrimination mainly reflected the intermittent or persistent negative psychological state of head and neck cancer patients after subjectively estimating or objectively experiencing exclusion, unfair speech or behavior from other social groups. Anxiety and depression mainly reflected the negative psychology of patients under multiple burdens, such as cancer pain, disfigurement dilemmas, and self-deprecation. Social phobia mainly reflected the actual conditions of disease concealment and self-isolation.

A total of 20 patients with head and neck cancer were invited to participate in cognitive interviews. For each item, all participants were asked the same question: "Can you understand and accept the content and meaning of the item?" Every participant's answer was affirmative. Therefore, no revision of the item content was needed. Finally, a preliminary HNCPDS consisted of 14 items was developed.

Validation of HNCPDS

Content validity

After two rounds of expert consultation, the I-CVIs of all 14 items in the preliminary HNCPDS were greater than 0.80. The results of the item analysis indicated that each item was strongly correlated with the HNCPDS, and the Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from 0.587 to 0.858 (r ≥ 0.30, P < 0.01) (Table 2). Each item was strongly correlated with the three subscales, and the Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from 0.473 to 0.926 (r ≥ 0.30, P < 0.01). Therefore, it was determined that the HNCPDS had good content validity.

Construct validity

The EFA results showed that the Kaiser‒Meyer‒Olkin (KMO) coefficient of the preliminary HNCPDS was 0.947, and the Bartlett’s test was 5027.496 (P < 0.001), which indicated that it was suitable for FA. Three common factors with characteristic roots greater than 1 were extracted by PCA, and the cumulative variance contribution rate was 75.416% (Table 2). The factor loading of each item in its dimension was greater than 0.55, so there was no need to remove any item from the HNCPDS (Table 2).

EFA results show that the distribution of 14 items in HNCPDS was consistent with our initial tri-dimensional theoretical model, which indicated that it had good construct validity. Therefore, Factor 1 was named social phobia, Factor 2 was named anxiety and depression, and Factor 3 was named cancer discrimination.

Criterion-related validity

The validity coefficients of the HNCPDS with the CSPDS and QLQ-C30 were 0.836 and 0.530, respectively (r ≥ 0.50, P < 0.01), which indicated that the HNCPDS had good CRV (Table 3).

Reliability

The Cronbach's alpha of the final HNCPDS was 0.954, and the Spearman-Brown coefficient was 0.955. The Cronbach's alpha values of the three subscales were 0.902, 0.906 and 0.915, and the Spearman–Brown coefficients were 0.894, 0.909 and 0.900. These results indicated that the final HNCPDS had good internal reliability. Three weeks after the first questionnaire survey was administered, 35 patients participated in the second survey. The test–retest results showed that the ICCs of the final HNCPDS and the three subscales were 0.845, 0.846, 0.814 and 0.810, which indicated that the final HNCPDS had good test–retest reliability.

Applicability

The average completion time of the 14-item HNCPDS was 14.31 ± 2.354 (range 8–22) minutes (≤ 20 min). A total of 480 HNCPDS questionnaires were distributed, and 435 valid questionnaires were recovered (the effective response rate was 90.63% ≥ 90%), which indicated that the final HNCPDS had good applicability. Finally, the final HNCPDS with 14 items was developed and validated.

Application of HNCPDS

Risk factors for HNCPDS

The HNCPDS scores of 435 participants were 14–67, with M (P25, P75) of 36 (21, 46), which proved that the patients with head and neck cancer generally had a strong psychosocial distress (Supplementary Table S1). One-way ANOVA indicated, statistically significant differences in scores of sex, age, area of residence, education level, monthly income, type of medical insurance, financial burden, tumor stage and personality (P < 0.01) (Table 1). The HNCPDS score was used as the dependent variable, and the above 9 statistically significant variables were used as independent variables. The normalized standardized residual histogram showed that HNCPDS scores were approximately normally distributed (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Multiple stepwise linear regression analysis revealed that financial burden (light or heavy), sex (male or female), age (< 45 years old or ≥ 45 years old) and personality (introvert or extrovert) were independent risk factors for patients' psychosocial distress (P < 0.05), and the variance inflation factor (VIF) of the four independent variables in the regression model was very close to 1 (Table 4).

QOL correlation analysis

The scores of HNCPDS were positively correlated with the QOL, global health, 5 functional domains, 3 symptom domains and 5 single items (except for dyspnoea) (P < 0.05), which indicated that patients with higher HNCPDS scores reported a lower QOL, poorer global health and function, and more prominent symptoms (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study showed that patients with head and neck cancer generally had a strong psychosocial distress, which was mainly manifested in three dimensions: cancer discrimination, anxiety and depression, and social phobia. Patients with head and neck cancer experience not only subjective and objective self-perception discrimination, but also anxiety and depression stemming from internal and external pressure. Furthermore, the lack of post-cancer communication with the outside world could easily result in psychological withdrawal among patients. Therefore, we developed a 14-item HNCPDS based on the modified classical test theory to assess psychosocial distress in head and neck cancer patients. Three common factors were extracted from HNCPDS by FA, and the three-factor correlation model had good content validity [I-CVIs were greater than 0.80, Pearson correlation coefficients were greater than 0.30 (P < 0.01)], construct validity [KMO coefficient was 0.947, Bartlett’s test was 5027.496 (P < 0.001), Cumulative variance contribution rate was 75.416%, and all factor loadings were greater than 0.55], reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.954, Spearman-Brown coefficient was 0.955, ICC was 0.845), and applicability (average completion time 14.31 ± 2.354 min and effective completion rate of 90.63%). Therefore, the HNCPDS could be used to estimate the associations of psychosocial distress such as cancer discrimination, anxiety and depression, and social phobia with head and neck cancer.

In comparison with previous anxiety and depression-related scales (HADS, GAD-7, PHQ-9, BDI-II)15,16,17,18, the HNCPDS was currently the sole specific psychosocial distress scale tailored for patients with head and neck cancer. It could assess negative psychological traits common among patients, as well as those unique to patients with head and neck cancer. Furthermore, compared with the TCSPDS and SSS, the HNCPDS had greater reliability and comprehensiveness. The reliability of the HNCPDS was greater than that of the TCSPDS (Cronbach's alpha = 0.867) and SSS (Cronbach's alpha = 0.930)19,20. Our qualitative study showed that most of the psychosocial distress experienced by patients with head and neck cancer stemmed not only from discrimination and stigma, but also from anxiety, depression, and social phobia toward cancer pain, disfigurement, self-deprecation, and self-isolation. Therefore, adding the anxiety and depression, and social phobia subscales may make the evaluation content more comprehensive. In addition, compared with the 20-item SSS and 31-item CLCSS20,21, the 14-item HNCPDS had obvious advantages in terms of applicability and convenience, which indicated that it was easier for patients to accept and understand, and was conducive to its popularization and application.

The HNCPDS scores of 435 participants ranged from 14 to 67, with M (P25, P75) of 36 (21, 46), so we recommend that participants score < 21 for mild psychosocial distress, 21–46 for moderate psychosocial distress, and > 46 for severe psychosocial distress. In addition, we also suggest that active and effective intervention measures should be taken in time for patients with moderate to severe psychosocial distress.

Interestingly, our study showed that financial burden, sex, age and personality were found to be independent risk factors for patients’ psychosocial distress. Patients with heavy financial burdens had higher levels of psychosocial distress. The high cost of treatment and long-term review of head and neck cancer has gradually become a focus of economic anxiety for patients38. Although medical insurance can be used to effectively reimburse some medical expenses, most patients still need to pay a significant portion of their personal expenses39. Due to social biases and misunderstandings, as well as the decline in physical fitness and work ability caused by treatment toxicity, this change not conducive to patient return to society, which may lead to temporary or permanent unemployment risks, and ultimately result in the patient bankruptcy40. However, the objective financial burden is often transforms into a self-perceived burden on patients. In addition, female patients had greater incidences psychosocial distress. The toxicity of treatment for head and neck cancer is unacceptable for the vast majority of patients, and includes image disfigurement, physiological function decline and mental and emotional changes, which may lead to negative psychology in patients that makes it difficult to achieve their own social value and maintain social and interpersonal relationships, this phenomenon is more pronounced in young female patients41. Furthermore, introverted patients tend to have stronger psychosocial distress. The changes brought about by head and neck cancer affect the mental health of patients by disrupting their lifestyle and interests, transforming their originally extroverted personality into introverted, manifested as a lack of talking and socializing, and further developed into depression and self-isolation42. Therefore, these risk factors should be one of the key points in our clinical work to pay attention to and improve the mental health of patients with head and neck cancer.

Notably, patients with higher HNCPDS scores had lower QOL, worse global health and function, and more prominent symptoms. Psychological health is an important component of overall health and one of the main evaluation indicators of QOL43. Due to the stereotype of cancer, people objectively experience fear and stigma toward cancer, which leads to patients suffering from considerable dissatisfaction and criticism from the general public44. Negative psychology factors such as fear of death, dysfunction, disfigurement and loss of belief may lead to anxiety and depression, and increase the risk of suicide and death45. Because of the lack of proper psychological counseling, patients often hesitate to pour or communicate with others for fear of harm to themselves or others, and may gradually develop social avoidance and self-isolation46. The above negative effects on the mental health of head and neck cancer patients may profoundly and permanently impair their QOL. Therefore, the HNCPDS will help with the early identification of these problems and facilitate the development and implementation of targeted health education, medical counseling, and psychological support based on the above risk factors. This may ultimately improve physical and mental health and QOL for patients with head and neck cancer.

However, because of limited sample size, as a multicenter exploratory study, our proposed classification criteria for psychosocial distress degree among head and neck cancer patients are used only for preliminary reference. In addition, the development and validation of the HNCPDS were conducted in a Chinese population, so the results of this study could only represent Chinese head and neck cancer patients. Therefore, we encourage researchers to translate the HNCPDS into different languages to further test its reliability, validity, and applicability in different countries and regions. With the consent of the corresponding author and without any commercial purpose, the researchers can use our developed HNCPDS for free.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that patients with head and neck cancer commonly experience significant psychosocial distress, and the HNCPDS proved to be effective and reliable for early identification and assessment of these problems. This tool could serve as a foundation for future health education, psychological counseling, and social support interventions, particularly in China. Timely and effective intervention measures targeting risk factors will aid in the prevention and alleviation of psychosocial distress among patients, ultimately enhancing their physical and mental well-being as well as their QOL.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-Cancer J. Clin. 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Zheng, R. S. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 46(3), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20240119-00035 (2024).

Amonoo, H. L. et al. Yin and Yang of psychological health in the cancer experience: Does positive psychology have a role?. J. Clin. Oncol. 40(22), 2402–2407. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.02507 (2022).

Tulk, J. et al. Rural-urban differences in distress, quality of life, and social support among Canadian young adult cancer survivors: A Young Adults with Cancer in Their Prime (YACPRIME) study. J. Rural Health. 40(1), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12774 (2024).

DeLamater, J. & Collett, J. Social Psychology 9th edn, 27–47 (Taylor & Francis Press, 2018).

Schultz, M. et al. Associations between psycho-social-spiritual interventions, fewer aggressive end-of-life measures, and increased time after final oncologic treatment. Oncologist. 28(5), e297–e294. https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyad037 (2023).

Velasco-Durantez, V. et al. Prospective study of predictors for anxiety, depression, and somatization in a sample of 1807 cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 14(4), 3188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53212-y (2024).

Carlson, L. E. Psychosocial and integrative oncology: Interventions across the disease trajectory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 74, 457–487. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032620-031757 (2022).

O’Donnell, E. K. et al. Quality of life, psychological distress, and prognostic perceptions in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer-Am. Cancer Soc. 128(10), 1996–2004. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34134 (2022).

Yücel, K. B. et al. Greater financial toxicity correlates with increased psychological distress and lower quality of life among Turkish cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 31(2), 137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07586-w (2023).

Soffer, M. Cancer-related stigma in the USA and Israeli mass media: An exploratory study of structural stigma. J. Cancer Surviv. 16(1), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01145-0 (2022).

Cherba, M. et al. Framing concerns about body image during pre- and post-surgical consultations for head and neck cancer: A qualitative study of patient–physician interactions. Curr. Oncol. 29(5), 3341–3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29050272 (2022).

Ivanova, A. et al. Body image concerns in long-term head and neck cancer survivors: prevalence and role of clinical factors and patient-reported late effects. J. Cancer Surviv. 17(2), 526–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01311-y (2023).

Ghazali, S. N. A. et al. Quality of life for head and neck cancer patients: A 10-year bibliographic analysis. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers/15184551 (2023).

Nikolovski, A. et al. Psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in individuals with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 46(7), 1230–1238. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2023.2182918 (2023).

Delamain, H. et al. Measurement invariance and differential item functioning of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 between working age and older adults seeking treatment for common mental disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 347, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.11.048 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Comparison of the EPDS and PHQ-9 in the assessment of depression among pregnant women: Similarities and differences. J. Affect Disord. 351, 774–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.219 (2024).

Ferreira-Maia, A. P., Gorenstein, C. & Wang, Y. P. Comprehensive investigation of factor structure and gender equivalence of the Beck Depression Inventory-II among nonclinical adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-024-02478-8 (2024).

Liu, Z. J. et al. Development and validation of the thyroid cancer self-perceived discrimination scale to identify patients at high risk for psychological problems. Front. Oncol. 13, 1182821. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1182821 (2023).

Kissane, D. W. et al. Preliminary evaluation of the reliability and validity of the Shame and Stigma Scale in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 35, 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.22943 (2013).

Cataldo, J. K. et al. Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: Psychometric testing of the cataldo lung cancer stigma scale. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 38(1), E46-54. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.E46-E54 (2011).

Lydiatt, W. M. et al. Head and Neck cancers-major changes in the American Joint Committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67(2), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21389 (2017).

Hamilton, A. B. & Finley, E. P. Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res. 280, 112516. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676360 (2019).

Cataldo, J. K. et al. Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: Psychometric testing of the cataldo lung cancer stigma scale. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 38(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.E46-E54 (2011).

Stubbings, S. et al. Development of a measurement tool to assess public awareness of cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 101(Suppl 2), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605385 (2009).

Feng, L. S. et al. Development and reliability and validity test of the Fear of Cancer Scale (FOCS). Ann. Med. 54(1), 2354–2362. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2113914 (2022).

He, H. et al. Development of the competency assessment scale for clinical nursing teachers: Results of a Delphi study and validation. Nurs. Educ. Today. 101, 104876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104876 (2021).

Kodweis, K. R. et al. Exploring the relationship between imposter phenomenon and Myers-Briggs personality types in pharmacy education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 87(6), 100076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpe.2023.100076 (2023).

Feng, L. S. et al. Development and validation of the cancer self-perceived discrimination scale for Chinese cancer patients. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 16(1), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0984-x (2018).

Aaronson, N. K. et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 (1993).

Fu, Y., Wen, Z. & Wang, Y. A Comparison of reliability estimation based on confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory structural equation models. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 82(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131644211008953 (2022).

Siraji, M. A., Jahan, N. & Borak, Z. Validation of the Bangla Communication Scale among Bangladeshi adolescents: A classical test theory and item response theory approach. Asian J. Psychiatr. 84, 103586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103586 (2023).

Hreinsson, J. P. et al. Factor analysis of the Rome IV Criteria for major disorders of gut–brain interaction (DGBI) globally and across geographical, sex, and age groups. Gastroenterology. 164(7), 1211–1222. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.033 (2023).

Schneider, S. et al. The Elemental Psychopathy Assessment (EPA): Factor structure and construct validity across three German samples. Psychol. Assess. 34(8), 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001126 (2022).

Aronson, K. I. et al. Validity and reliability of the fatigue severity scale in a real-world interstitial lung disease cohort. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. 208(2), 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202208-1504OC (2023).

Viladrich, C., Angulo-Brunet, A. & Doval, E. Un viaje alrededor de alfa y omega para estimar la fiabilidad de consistencia interna. An Psicol-Spain. 33(3), 755. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.268401 (2022).

Batchelor, J. M. et al. Using the Vitiligo Noticeability Scale in clinical trials: Construct validity, interpretability, reliability and acceptability. Br. J. Dermatol. 187(4), 548–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21671 (2022).

Jella, T. K. et al. Prevalence, trends, and demographic characteristics associated with self-reported financial stress among head and neck cancer patients in the United States of America. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 42(6), 103154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103154 (2021).

Li, D. et al. Association of public health insurance with cancer-specific mortality risk among patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A prospective cohort study in China. Front. Public Health. 11, 1020828. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1020828 (2023).

Hueniken, K. et al. Measuring financial toxicity incurred after treatment of head and neck cancer: Development and validation of the Financial Index of Toxicity questionnaire. Cancer-Am. Cancer Soc. 126(17), 4042–4050. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33032 (2020).

Graboyes, E. M. et al. Mechanism underlying a brief cognitive behavioral treatment for head and neck cancer survivors with body image distress. Support Care Cancer. 32(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08248-7 (2023).

Haraj, N. E., El Aziz, S. & Chadli, A. Anxiety and depression in patients treated for differentiated thyroid microcarcinoma. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 35, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2020.35.133.12877 (2020).

Thaduri, A. et al. 363P Effect of financial distress and mental well-being of patients with early vs advanced oral cancer on informal caregiver’s quality of life: A prospective real-world data from public health sector hospital. Ann. Oncol. 34, S1611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.471 (2024).

Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M. et al. The course of health-related quality of life in the first 2 years after a diagnosis of head and neck cancer: The role of personal, clinical, psychological, physical, social, lifestyle, disease-related, and biological factors. Support Care Cancer. 31(8), 458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07918-w (2023).

Andersen, B. L. et al. Management of anxiety and depression in adult survivors of cancer: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 41(18), 3426–3453. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.00293 (2023).

Sella-Shalom, K. et al. The association between communication behavior and psychological distress among couples coping with cancer: Actor-partner effects of disclosure and concealment. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 84, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.07.005 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to all of the head and neck cancer patients for their participation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Program of Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Yunnan Province (No. QN202214), Yunnan Provincial Education Department Fund Project (No. JX0036) and Jiangxi Provincial Health Commission Fund (No. 202311199).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J.L.: Study design, ethical approval, fund acquisition, and manuscript modification. Z.H.L.: Fund acquisition, data collection, and guidance. J.X., F.L., F.Y.W.: Data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation. X.X.W., L.L.L.: Data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jun, X., Feng, L., Fangyun, W. et al. Development and validation of the head and neck cancer psychosocial distress scale (HNCPDS) to identify patients at high risk for psychological problems : a multicenter study. Sci Rep 14, 18591 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67719-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67719-x