Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of thigh muscle assessed by CT images to predict overall mortality in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). This was a multicenter cohort study including adults (≥ 18 years old) newly diagnosed with CRC, who performed a diagnostic computed tomography (CT) exam including thigh regions. CT images were analyzed to evaluate skeletal muscle (SM in cm2), skeletal muscle index (SMI in cm2/m2), and skeletal muscle density (SMD in HU). Muscle abnormalities (low SM, SMI, and SMD) were defined as the values below the median by sex. Kaplan–Meyer curves and hazard ratios (HRs) for low SM, SMI and SMD were evaluated for overall mortality, stratified by sex. A total of 257 patients were included in the final analysis. Patients’ mean age was 62.6 ± 12.1 years, and 50.2% (n = 129) were females. In males, low thigh SMI was associated with shorter survival (log-rank P = .02). Furthermore, this low thigh SMI (cm2/m2) was independently associated with higher mortality rates (HR adjusted 2.08, 95% CI 1.03–4.18). Our additional findings demonstrated that low SMD was independently associated with overall mortality among early-stage patients (I–III) (HR adjusted 2.78, 95% CI 1.26–6.15).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skeletal muscle mass (SMM) evaluation is essential to assessing overall health1,2. It is pivotal in understanding and diagnosing conditions related to abnormal muscle, including sarcopenia and malnutrition1,2. In patients with cancer, low SMM correlates to surgical complications3,4,5, chemotherapy toxicity6,7,8, impaired quality of life9,10 and poor survival11,12,13,14,15. In oncology care, computed tomography (CT) is as a valuable reference method for accurately quantifying SMM16,17. It is widely utilized as an imaging technique to opportunistically assess body composition, including muscle parameters16,17,18. The landmark at the third lumbar vertebra (L3) in the abdominal region is widely utilized in studies due to its robust correlation with whole-body SMM19.

Low SMM is prevalent in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC)20,21,22. CRC is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers worldwide23,24, ranking as the third most common cancer in men and the second in women23. Low SMM and sarcopenia are additional factors contributing to the impaired prognosis in these patients25,26,27,28,29, emphasizing the critical role of assessing body composition. However, this assessment in patients with CRC presents unique challenges, particularly for those who have undergone colostomy. This surgical procedure can affect the evaluation of SMM using CT images at the L3 landmark. The colostomy position in the abdominal wall alters the region’s muscle anatomy, potentially compromising the accuracy and practicality of SMM measurements (refer to Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, it is necessary to explore alternatives landmarks, such as the thigh region. Since this region can be assessed using low radiation dose protocol30, it can be an alternative when CT exam does not be done.

Our previous work has demonstrated an excellent agreement between muscle characteristics at the L3 and thigh landmarks in a healthy population30, reinforcing the potential of this level. Although low SMM in the lower limbs (including thigh muscle) has been associated with higher mortality and other adverse outcomes in both healthy31,32 and clinical populations33,34, few studies have evaluated the thigh muscle using CT as an indicator of low SMM in patients with cancer. Supporting this assertion, a meta-analysis examining the impact of CT-based sarcopenia (based on SMI) on adverse outcomes in CRC patients includes studies that specifically evaluate muscle mass at the L3 level35,36. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of thigh muscle, as measured by CT-images, in predicting overall mortality among patients with CRC.

Results

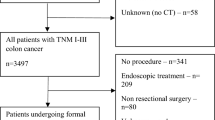

Of the 568 patients in the original cohort, 272 had CT images that included the thigh muscle. Fifteen patients were excluded due to the presence of artifacts or anatomical variations in the CT images (e.g. distortions hindering image sharpness; tumor obstructions). A total of 257 subjects (with available thigh CT scans) were included in the final analysis. A detailed flowchart of participants is presented in Fig. 1. The mean age was 62.6 ± 12.1 years; 58.4% were non-Caucasian, and 50.2% were females. Table 1 presents socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to sex. SM, SMI and SMD from thigh and L3 levels were positively and strongly correlated: ρ 0.83, P < .001; ρ 0.73, P < .001; ρ 0.79, P < .001, respectively (data not shown in tables).

Data was available from a median follow-up of 36 months (IQ range: 24.1–59.2), with the maximum observation period extending over 14.5 years. Overall mortality occurred in 26.5% of the sample. Table 2 presents univariate sex-stratified survival associations with clinical and nutritional characteristics. Tumor stage was associated with a higher relative risk for mortality among both males and females (P = .001; P < .001, respectively). Low thigh SMI was associated with a high relative risk of mortality, specifically among males (P = .020). No other variable was associated with mortality.

KM curves revealed notable differences in survival rates. Among males, low thigh SMI (cm2/m2) was associated with a shorter survival (log-rank P .020), while among females, no skeletal muscle parameter was associated with survival (Fig. 2). Cox regression analysis showed no associations between low thigh SM or SMD with mortality, for both males and females, in its crude and adjusted models. However, low thigh SMI (cm2/m2) was independently associated with higher mortality rates among males (Table 3), even after adjusting for age, tumor site, and type of treatment. An additional Cox model, which accounted for the disease stage, was constructed. However this variable was subsequently excluded from the Cox analysis due to multicollinearity issues resulting in parameters approaching infinity and a lower goodness-of-fit. After investigating the outcome concerning the clinical TNM stages, we found that a low SMD was independently associated with mortality in stages I–III (HR adjusted 2.78, 95% CI 1.26 to 6.15).

Discussion

The importance of assessing body composition in patients with cancer, particularly using CT images, is well established. While previous literature has extensively explored SMM measurement at the L3 level, its evaluation at the thigh level is a relatively novel approach. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess muscle thigh using CT and its association with mortality in patients with CRC. Our main findings demonstrated that a low thigh SMI was independently associated with shorter overall survival in men with CRC. Furthermore, a low SMD was independently associated with shorter overall survival in early-stage tumors (I–III).

Although approximately 50% of the SMM tissue is located in the lower limbs, with a substantial portion in the thigh region37, most studies focused on measuring SMM at the L3 region. A recent systematic review, encompassing 32 studies in patients with cancer, evaluated the most commonly used landmarks for SMM assessment when the L3 was not available38. This analysis reviewed 32 studies with retrospective and cross-sectional designs. Interestingly, none evaluated muscle mass in the thigh region. When analyzing other populations, more evidence emerges. For instance, in a diverse adult population (n = 39,804), low SMM at the thigh level, assessed by magnetic resonance images, was a strong, and independent predictor of all-cause mortality during a follow-up period of 2.9 ± 1.4 years after imaging39.

The anatomical location chosen for measuring SMM can markedly affect the prediction of adverse events. For example, Arribas et al.40, in a prospective cohort study assessing body composition, monitored four anatomical levels: upper arm, thigh, chest and abdomen using CT images from 38 middle-aged male patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck at two time points. The median interval between scans was 224 days. Their findings indicated that low SMM in the tight was significantly higher than in the other regions, underscoring the importance of thigh muscle assessment whenever possible.

Advancements in medical imaging have enabled the noninvasive assessment of human body composition, thereby enriching our understanding of the variations between sexes. Our research group has previously shown that the relationship between SMM, strength, and adverse outcomes is more pronounced in males than in females11,41,42. Additionally, sex hormones could be contributing factors to these sex-related differences. In men, testosterone plays a pivotal role in developing and maintaining SMM and strength43, which becomes particularly relevant for patients with cancer undergoing treatments like chemotherapy, with its myriad side effects13,14. This may partly explain our observation that thigh muscle mass is a predictor of mortality predominantly in males.

Another possible explanation is the aging process, as a substantial proportion of our cohort (42.8%) was over 65 years old. Although aging has been associated with loss of SMM, independent of sex, and with greater loss of SMM in the lower body44, men have a greater magnitude of SMM loss compared to women45. As they age, men become increasingly vulnerable to muscle loss due to decreased anabolic hormones such as growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor, and testosterone. This hormonal decline could exacerbate clinical outcomes, thereby explaining the sex differences noted in our study46. Collectively, these findings suggest that low lower-limb SMM in males with cancer may be more clinically meaningful when compared to females, indicating the need for more intense interventional approaches to counteract lower-limb SMM loss in men.

In our study, given the absence of established cut-off values for thigh muscle measurements, we chose to use the median value of our sample’s data distribution. We acknowledge this decision as a potential limitation in our analysis. This median point was selected noting that nearly half of our cohort was diagnosed at an advanced stage (III and IV TNM), which likely impacted their SM (leading to a greater prevalence of low SM). Alternatively, SM variables could be treated as continuous data. Bardoscia et al.47 assessed SM in 225 patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radical chemo-radiation therapy using retrospective CT scans. SMI and SMD were both measured at the L3 and thigh levels. In the absence of a specific thigh-level cutoffs, the authors test these as continuous variables. In contrast, for the L3 region, they applied cutoffs based on the sample distribution and existing literature47,48. Their results showed that only L3-SMD (not L3-SMI) exhibited a significant association with survival. However, when assessing the indices at the thigh level as continuous variables, an increase in both SMI and SMD were significant protective factors for all survival outcomes.

Our additional findings underscored the prognostic significance of a low SMD in patients with early-stage tumors (I–III). We observed that poor muscle composition, as indicated by SMD, rather than low muscle mass alone, independently correlated with overall mortality. This contributes significantly to the expanding evidence emphasizing the importance of evaluating this morphological marker of muscle quality. Our results are supported by a growing body of evidence indicating that alterations in muscle composition may manifest earlier than changes in muscle mass, potentially impacting strength and leading to increased mortality49,50.

Our study has limitations that warrant acknowledgment. The convenience sample and retrospective data collection preclude the establishment of causal relationships. Furthermore, unmeasured confounding variables were not considered in our regression models, potentially skewing our results. The reliance on medical records may introduce bias in the overall mortality frequency, providing different follow-up periods, limiting the collection of detailed clinical data (e.g., specific type of treatment, and specific acquisition contrast phase). Future studies with larger sample size and prospective design are needed to overcome these limitations. These studies could explore additional landmarks (e.g. gluteus). On a positive note, our study contributes valuable insights to the growing body of evidence by investigating the relationship between baseline thigh SMM and mortality in patients with CRC.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate an association between thigh SMI and SMD and overall mortality in newly diagnosed patients with CRC. From a clinical perspective, our findings underscore the prognostic significance of assessing CT-derived lower-limb SMM in CRC.

Materials and methods

Study design and subjects

This multicenter retrospective cohort study included patients (≥ 18 years old) newly diagnosed with CRC and referred to a specialized cancer treatment center. Inclusion criteria were individuals who had CT images of the thigh area within ± 90 days of diagnosis, as well as body weight (kg) and height (m) within the same period. The availability of abdominal CT scans was conveniently also included For secondary analysis purposes. Data from three oncology centers across two different regions of Brazil were analyzed, encompassing three states: Southeast (104 patients from Rio de Janeiro, RJ) and Northeast (111 patients from Fortaleza, CE, and 42 patients from Natal, RN). Individuals with concomitant consumptive diseases (AIDS, non-cancerous liver diseases, tuberculosis), or with anasarca/leg edema which made it impossible to analyze their CT images were excluded. This study was in accordance of with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (protocol number 4.431.753, CAAE 40,019,020.0.1001.5292). Due to the retrospective nature of data collection, informed consent was waived by the Research Ethics Committee of the coordinating center, Onofre Lopes University Hospital, Natal, RN, Brazil.

Procedures and outcome

A web-based application (Research Electronic Data Capture—REDCap) was used to collect data from centers and create a database. Patient characteristics such as age at diagnosis, comorbidities, ethnicity, site, and tumor stage, were extracted from electronic medical records. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using height (m2) and weight (kg) data closest (up to three months) to the CT scan evaluation, and then classified according to the criteria of the World Health Organization: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 a 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25 a 29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2)51. Data regarding treatment administered during this period, including surgical procedures, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy, were also recorded. Overall survival was measured from the date of the CT scan to either the date of death or the end of follow-up. Mortality was verified in the medical records or asked by phone contact, when the information was unavailable. Patients were followed for a maximum follow-up duration of almost 15 years.

Skeletal muscle mass analysis

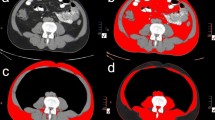

All analyzed CT images were under contrast through manual segmentation with Slice-O-Matic software (v.5, Tomovision®). Hounsfield Unit (HU) boundaries from − 29 to + 150 were used to quantify SMM52. Muscle thigh was analyzed according to a previous study of our group30. Briefly, was selected the area at the level of the lower margin of the lesser trochanter of the femur and included the following muscles: quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, vastus lateralis), pectineus, tensor fasciae latae, iliopsoas, sartorius, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor minimus, adductor magnus, gracilis, semitendinosus and gluteus maximus. Both legs were assessed, and the sum of muscle areas was considered to quantify thigh skeletal muscle area (SM, in cm2). The SMI (cm2/m2) was calculated as a ratio between SM and height squared (m2). The skeletal muscle radiodensity (SMD) was determined by the mean Hounsfield Units (HU) value of both legs. Figure 3 demonstrates an example of CT image at thigh level in our cohort.

CT images at the thigh level showing two patients of our cohort. Image (A) refers to a 56-year-old male patient with skeletal muscle cross-sectional area (SMA) of 265 cm2 and skeletal muscle radiodensity (SMD) of 60.1 Hounsfield Units (HU). Image (B) refers to a 56-year-old female patient with SMA of 193.5 cm2 and SMD of 42.7 (HU).

Muscle abnormalities were categorized based on sample distribution (median), as follows: (i) low SM < 258.3 for males, < 179.8 for females; (ii) low SMI < 93.8 for males, < 78 for females; (iii) low SMD < 38.2 for males, < 32.6 for females. For additional analysis, CT images were processed to measure tissue cross-sectional area (cm2) at the third lumbar vertebra (L3). Total area at L3 was quantified for SM in cm2 encompassing psoas, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, transversus abdominus, external and internal obliques, and rectus abdominus muscles, as well as SMD in HU. CT-derived HU thresholds for SMD were also defined within a range of − 29 HU to + 150.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using MedCalc version 22.0.0.9 software (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium) and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed data were described using mean ± standard deviation (SD). Means were compared using independent Student "t" test. Non-normally distributed data were described using medians and interquartile (IQ) ranges. Medians were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as absolute frequencies (N) and relative percentages (%). Comparisons of categorical data were conducted using Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s Exact tests, when appropriate. Spearman’s correlation test was employed to analyze the relationship between muscle parameters from L3 and thigh level. The magnitude of these analyses was categorized as follows: very strong (ρ = 0.90–1.00), strong (ρ = 0.70–0.90), moderate (ρ = 0.50–0.70), weak (ρ = 0.30–0.50), or negligible (ρ = 0.00–0.30). Missing data was not imputed. Kaplan–Meier (KM) curves were constructed to evaluate the association between CT-based muscle abnormalities and overall survival. P values (< .05) for the Log-rank, Breslow, and Tarone-Ware tests were examined to assess the significance of the KM analysis over the entire follow-up period. A Cox proportional hazards analysis was conducted in both its crude and adjusted models to assess the independent associations. Adjustments were made based on prognostic factors. Statistical significance was set at P < .05 for all analyses.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48, 1–16 (2018).

Fayh, A. P. T., de Sousa, I. M. & Gonzalez, M. C. New insights on how and where to measure muscle mass. Curr. Opin. Support Palliat Care 14(4), 316–323 (2020).

De Carvalho, A. L. M. et al. Low skeletal muscle radiodensity is the best predictor for short-term major surgical complications in gastrointestinal surgical cancer: A cohort study. PLoS One 16(2), e0247322 (2021).

Chen, W. Z. et al. Impact of visceral obesity and sarcopenia on short-term outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Dig. Dis. Sci. 63, 1620 (2018).

Martin, L. et al. Assessment of computed tomography (CT)-defined muscle and adipose tissue features in relation to short-term outcomes after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A multicenter approach. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25(9), 2669–2680 (2018).

da Rocha, I. M. G. et al. Is cachexia associated with chemotherapy toxicities in gastrointestinal cancer patients? A prospective study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 10(2), 445–54 (2019).

Mazzuca, F. et al. Lean body mass wasting and toxicity in early breast cancer patients receiving anthracyclines. Oncotarget 9(39), 25714–25722 (2018).

Prado, C. M. M. et al. Body composition as an independent determinant of 5-fluorouracil—Based chemotherapy toxicity. Clin. Cancer Res. 13(11), 3264–3268 (2007).

Derksen, J. W. G. et al. The association between changes in muscle mass and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 31(11), 919–928 (2020).

Bye, A. et al. Muscle mass and association to quality of life in non- small cell lung cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 8, 759–767 (2017).

Sousa, I. M. et al. Low calf circumference is an independent predictor of mortality in cancer patients: A prospective cohort study. Nutrition 79–80, 110816 (2020).

de Sousa, I. M. & Fayh, A. P. T. Is the ECOG-PS similar to the sarcopenia status for predicting mortality in older adults with cancer? A prospective cohort study. Support Care Cancer 31(6), 370 (2023).

Jung, H. W. et al. Effect of muscle mass on toxicity and survival in patients with colon cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 23(3), 687–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2418-6 (2015).

Prado, C. M. et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 9(7), 629–635 (2008).

Xiao, J. et al. Association of low muscle mass and low muscle radiodensity with morbidity and mortality for colon cancer surgery. JAMA Surg. 155, 942 (2020).

Ryan, A. M. et al. Cancer-associated malnutrition, cachexia and sarcopenia: The skeleton in the hospital closet 40 years later. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 75(2), 199–211 (2016).

Prado, C. M. M. & Heymsfield, S. B. Lean tissue imaging: A new era for nutritional assessment and intervention. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 38(8), 940–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607114550189 (2014).

de Liguori, A. A. L. & Fayh, A. P. T. Computed tomography: An efficient, opportunistic method for assessing body composition and predicting adverse outcomes in cancer patients. Radiol. Bras. 56(6), VIII–IX (2023).

Shen, W. et al. Total body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: Estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional image. J. Appl. Physiol. 97(6), 2333–8 (2004).

Caan, B. J. et al. Explaining the obesity paradox: The association between body composition and colorectal cancer survival (C-SCANS study). Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 26(7), 1008–1015 (2017).

Daly, L. E., Prado, C. M. & Ryan, A. M. A window beneath the skin : how computed tomography assessment of body composition can assist in the identification of hidden wasting conditions in oncology that profoundly impact outcomes. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 77, 135–151 (2018).

da Silva Nascimento, M. L. et al. Examining variations in body composition among patients with colorectal cancer according to site and disease stage. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61790-0 (2024).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71(3), 209–249 (2021).

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Latest global cancer data: Cancer burden rises to 18.1 million new cases and 9.6 million cancer deaths in 2018. Ganeva (2018).

Boer, B. C. et al. Skeletal muscle mass and quality as risk factors for postoperative outcome after open colon resection for cancer. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 31(6), 1117–1124 (2016).

Souza, N. C. et al. Comparative Analysis between computed tomography and surrogate methods to detect low muscle mass among colorectal cancer patients. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 44, 1328 (2019).

Kroenke, C. H. et al. Muscle radiodensity and mortality in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer 124(14), 3008–3015 (2018).

Brown, J. C. et al. The deterioration of muscle mass and radiodensity is prognostic of poor survival in stage I–III colorectal cancer: A population-based cohort study (C-SCANS). J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 9(4), 664–672 (2018).

De Sousa, I. M., Silva, F. M., das Virgens, I. P. A., Costa, E. C. & Fayh, A. P. T. Independent and joint association of sarcopenia and frailty with mortality in older patients with gastrointestinal cancer: A cohort study with prospective data collection. Support Care Cancer 32(1), 1–8 (2024).

de Medeiros, G. O. C. et al. Comparative assessment of abdominal and thigh muscle characteristics using CT-derived images vio Cunha de Medeiros a, Iasmin Matias de Sousa a, Gabriela Villa c. Nutrition 99–100, 111654 (2022).

Farsijani, S. et al. Body composition by computed tomography vs dual- energy X-ray absorptiometry: Long-term prediction of all-cause mortality in the health ABC cohort. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76(12), 2256–2264 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. Influencing factors for the decline of limb muscle strength and the association with all-cause mortality: evidence from a nationwide population-based cohort study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 34(2), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-01940-w (2022).

Quinlan, J. I. et al. Impaired lower limb muscle mass, quality and function in end stage liver disease: A cross-sectional study. Exp. Physiol. 108(8), 1066–1079 (2023).

Fukasawa, H. et al. Lower thigh muscle mass is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly hemodialysis patients. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 71(1), 64–69 (2017).

He, J., Luo, W., Huang, Y. & Song, L. Sarcopenia as a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer: An updated meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 13, 1247341 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Guo, X., Zhang, Q. & Id, Y. Y. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in patients with rectal cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 17(6), e0270332. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270332 (2022).

Janssen, I. A. N., Heymsfield, S. B., Wang, Z. I. M. & Ross, R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. J. Appl. Physiol. 89, 81–88 (2000).

Vangelov, B., Bauer, J., Kotevski, D. & Smee, R. I. The use of alternate vertebral levels to L3 in computed tomography scans for skeletal muscle mass evaluation and sarcopenia assessment in patients with cancer: A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 127, 722–735 (2022).

Linge, J., Petersson, M., Forsgren, M. F., Sanyal, A. J. & Leinhard, O. D. Adverse muscle composition predicts all-cause mortality in the UK Biobank imaging study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12, 1513–1526 (2021).

Arribas, L. et al. Assessing dynamic change in muscle during treatment of patients with cancer: Precision testing standards. Clin. Nutr. 41(5), 1059–1065 (2022).

Barbalho, E. R. et al. Is skeletal muscle radiodensity able to indicate physical function impairment in older adults with gastrointestinal cancer ?. Exp. Gerontol. 125(May), 110688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2019.110688 (2019).

de Alves, C. P. L. et al. Agreement between upper and lower limb measures to identify older adults with low skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass and muscle quality. PLoS One 17(1), e0262732 (2022).

Wells, J. C. K. Sexual dimorphism of body composition. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 21(3), 415–430 (2007).

Bredella, M. A. Sex differences in body composition. In Sex and Gender Factors Affecting Metabolic Homeostasis, Diabetes and Obesity (ed. Mauvais-Jarvis, F.) 9–27 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Goodpaster, B. et al. Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: The Health ABC Study. J. Appl. Physiol. 90, 2157–2165 (2001).

Roubenoff, R. & Hughes, V. A. Sarcopenia: Current concepts. J. Gerontol. Med. Sci. 55(12), 716–724 (2000).

Bardoscia, L. et al. Impact of low skeletal muscle mass and quality on clinical outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing (chemo) radiation. Front. Nutr. 9, 994499 (2022).

Martin, L. et al. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J. Clin. Oncol. 31(12), 1539–1547 (2013).

Perkisas, S., De Cock, A., Verhoeven, V. & Vandewoude, M. Physiological and architectural changes in the ageing muscle and their relation to strength and function in sarcopenia. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 7(3), 201–206 (2016).

da Costa Pereira, J. P. et al. Strength-to-muscle radiodensity: A potential new index for muscle quality. Clin. Nutr. 43(7), 1667–74 (2024).

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

Mitsiopoulos, N. et al. Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J. Appl. Physiol. 85(1), 115–122 (1998).

Funding

Partial financial support was received from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (Grant 001/2020 PROPESQ), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001 and Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). APTF, ECC and MCG received a productivity scholarship from the CNPq. The supporting sources had no involvement or restrictions regarding this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M.C.F., M.C.G., C.M.P. and A.P.T.F. contributed to the conception and design of the research; G.M.C.F., A.L.M., S.M.M.V.V., G.V.C., L.B.M. and N.A.B. conducted the acquisition of the data; G.O.C.M., N.A.B. and V.A.A. analyzed the computed tomography images, G.M.C.F., J.P.C.P., E.C.C., M.C.G., C.M.P. and A.P.T.F. contributed to the analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed, interpreted, and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, G.M.C., da Costa Pereira, J.P., Miranda, A.L. et al. Thigh muscle by CT images as a predictor of mortality in patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 14, 17267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68008-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68008-3