Abstract

Although antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) alone fosters hope for the treatment of cancer, the effect of single drug treatment is limited and the safety profile of ADC and ICI therapy remains unclear. This meta-analysis aimed to examine the efficacy and safety of the combination of ADC and ICI therapy. This study type is a systematic review and meta-analysis. Literature retrieval was carried out through PubMed, Embase, Cochrane from inception to Jun. 5, 2024. Then, after data extraction, overall response rate (ORR) and adverse effects (AEs) were used to study its efficiency and safety. Publication bias was also calculated through Funnel plot, Begg's Test and Egger's test. Heterogeneity was investigated through subgroup and sensitivity analysis. The research protocol was registered with the PROSPERO (CRD42023375601). A total of 12 eligible clinical studies with 584 patients were included. The pooled ORR was 58% (95%CI 46%, 70%). Subgroup analysis showed an ORR of 77% (95%CI 63%, 91%) in classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) and an ORR of 73% (95%CI 56%, 90%) in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). The most common AEs was peripheral neuropathy (38.0%). Meanwhile, AEs on skin (13.1–20.0%) and digestive system (9.0–36.0%) was hard be overlooked. ADC + ICI therapy may be recommended in cancer treatment, especially in cHL and NHL. However, strategies to manage toxicities warranted further exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer, with dismal prognosis, was responsible for 19.3 million new cases and 10 million deaths globally in 20201. Every year, there is a substantial increase and the number is still growing. While conventional chemotherapies exhibit non-negligible adverse effects throughout the whole body, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), often referred to as “bio-missile”, elevate precision treatment to new heights by targeting and efficiently killing cancer cells with fewer side effects. From a structure- or function-based perspective, ADC is a targeted agent that connects a monoclonal antibody (mAb) with a cytotoxic drug via a linker2. With this particular structure, ADC is able to specifically recognize a cellular surface antigen expressed on the cancer cells and deliver a toxic payload at the tumor site, thus inducing further apoptosis and reducing systemic exposure to healthy tissue3,4.

After the evolution of ADC development, the new generation has significantly improved in specificity and safety, featuring various formats each with unique advantages5. Furthermore, ADC has been approved for successive indications in breast cancer (BC)6, urothelial cancer (UC)7,8, gastric cancer (GC)9, classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) 29685160 et al. Recent trials also highlighted the efficacy and safety profiles of ADC in the prostate cancer treatment10. However, pharmacokinetics, target specific payload release, homogeneous distribution of anticancer drug, potential adverse effects and tolerability have been constantly hindering ADC from achieving theoretically positive therapeutic effects in the clinical setting11.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), another widely used anti-tumor drug, can strengthen the immune attack and promote tumor killing by releasing the inhibitory brakes of T cells12. 11 ICIs have been approved in the United States until March 202313. However, no matter the conventional ICIs or the novel antibodies such as LAG-3, TIM-3, and so on14, monotherapy is restricted by the mutation status of certain genes, limited efficacy in subsequent line treatment15,16 and off-target toxicity. Also, primary and acquired drug resistance is hard to be neglected, which may be correlated with the aberrations of immunogenicity, signaling-associated mutations, the level of extracellular vesicles and tumor microenvironment17.

The combination strategy of ADCs and ICI is strongly supported by a biological rationale. It has been reported that specific payloads of several ADC could trigger direct activation and maturation of dendritic cells18,19,20, leading to a growth of T cells. With the massive infiltration of T cells, the response of tumor cell to ICI will increase. Moreover, ADC could also stimulate both innate and adaptive immunity21,22 by inducing immunogenic cell death23, that is also a key way for ADC to perform its killing effect. Simultaneously, this synergistic effect was also observed in a mice trial, which confirmed that ADC-induced antitumor immunity was facilitated by ICI24. Preliminary results and ongoing trials have also reported encouraging safety and efficacy data, particularly with ladiratuzumab vedotin25,26. Thus, it seems feasible that the combination of ADC and ICI may hold the promise to improve efficacy while overcome the harsh challenges of monotherapy, such as a limited subset of patients and drug resistance.

Overall, ADC and ICI are rapidly used in treatment landscape. To optimize their application, it’s necessary to comprehensively evaluate the clinical implications and irAEs of their combinations. However, there is no study summarizing efficacy and safety of ADC and ICI combinations. Therefore, to fill this gap, this meta-analysis is carried out to figure out the efficacy and safety in patients treated with ADC and ICI combination therapy. Ulteriorly, this meta-analysis is reckoned to provide information on the high-quality treatment regimen for combinations.

Results

Literature search and patients characteristics

According to the proposed search strategy, 3079 publications were retrieved. After removing duplications, there were 2546 articles obtained. Then, by screening title and abstract only, 159 articles were assessed for eligibility. Finally, after assessing full text of the remaining articles, 12 studies were included in qualitative synthesis. The specific selection steps are summarized in Fig. 1.

A total of 584 patients were enrolled in our study. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 90 years across all studies. The median follow-up period ranged from 1.00 to 49.90 months. Of the 12 eligible studies, four were randomized, four were non-randomized, three were single-armed, one was retrospective case review. The regimens included sacituzumab govitecan (SG) + pembrolizumab (Pembro), brentuximab vedotin (BV) + nivolumab (Nivo), trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) + atezolizumab (Atezo), BMS-986148 + Nivo, enfortumab vedotin (EV) + Pembro, BV + Pembro, Datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) + Pembro, and Tisotumab Vedotin (TV) + Pembro. There were six tumor types in our study: three studies on urothelial cancer (UC), five studies on classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), a study on non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) as primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL), a study on breast cancer (BC), a study on Advanced solid tumors a study on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and a study on recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer (r/m CC). The main characteristics and results are shown in Table 1.

Quality assessment

One included study (Rottey 2022) was assessed as serious based on the ROBINS-I tool (Supplementary Table 1). Five studies (Grivas 2022, Advani 2021, Cheson 2020, Hoimes 2022, NCT 03138499) was rated as moderate. The left six studies (Zinzani 2019, Emens 2020, Massaro 2022, Rosenberg 2022, NCT 04526691, Vergote 2023) was labelled as low. The result of GRADE demonstrates that the quality of evidence is moderate (Supplementary Table 2).

Efficacy

All the 12 studies reported an overall response rate (ORR) as the clinical activity outcome. The pooled ORRs was 58% (95% confidence interval (CI): 46%, 70%) (Fig. 2). As significant heterogeneity (I2 = 89.54%, p < 0.01) was observed, the random-effects model was adopted.

Subgroup analyses

Histologic subtype

All studies provided ORR data according to histologic subtype (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1A). Three studies on UC had usable ORR data and the pooled ORR was 60% (95%CI 42–78%) with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 81.6%, p = 0.010). Four studies on cHL provided ORR data. The pooled ORR was 77% (95%CI 63–91%), and heterogeneity existed (I2 = 68.7%, p = 0.020). One study on NHL reported an ORR of 73% (95%CI 56–90%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). The study on BC reported an ORR of 45% (95%CI 36–53%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). Additionally, the study on advanced solid tumors reported an ORR of 20% (95%CI 5–35%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). In the study on NSCLC, the pooled ORR was 37% (95%CI 22–52%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). The study on CC reported an ORR of 41% (95%CI 23–58%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001).

Regimen

All studies provided ORR data according to regimen (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1B). SG combined with Pembro resulted in an ORR of 41% (95%CI 25–57%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). BV combined with Nivo were given in four studies, and the ORR was 73% (95%CI 61–86%) with heterogeneity (I2 = 62.6%, p = 0.030). T-DM1 combined with Atezo showed a pooled ORR of 45% (95%CI 36–53%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). Additionally, the pooled ORR were 20% (95%CI 5–35%) in BMS-986148 combined with Nivo, without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). Two studies on EV combined with Pembro reported an ORR of 68% (95%CI 59–77%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.34). Moreover, BV combined with Pembro resulted in an ORR of 90% (95%CI 71–109%) and an ORR of 37% (95%CI 22–52%) was reported in Dato-DXd combined with Pembro, without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001). TV combined with Pembro resulted in an ORR of 41% (95%CI 23–58%) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, p ≤ 0.001).

Safety

As shown in Table 3, the most common adverse effects (AEs) of ADC combined with ICI was peripheral neuropathy (38.0%). However, only 5.0% of the patients developed high-grade (≥ 3) peripheral neuropathy. Gastrointestinal toxicities included abdominal pain (9.0%), decreased appetite (36.0%), diarrhea (20.1%) and nausea (24.0%). Despite the high incidence rates of gastrointestinal AEs of all grades, the risk of grade 3 AEs or worse was just 0.9% to 4.3%. AEs on skin, such as pruritus, maculopapular rash and rash, developed in more than 20.0% of the patients and the risks of high-grade AEs (1.0% to 4.1%) on skin was lower than that of all-grade AEs. Moreover, 30.0% of the patients suffered from fatigue, 2.9% of whom had high-grade fatigue. AST increased (15.8%) is another common AEs, but only 1.3% of the patients suffered from high-grade AST increased.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Funnel plot, Begg's Test and Egger's test were carried out to access publication bias in this study. Slight asymmetric distribution was found in the funnel plots (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating the existence of publication bias. Therefore, we performed Begg's Test and Egger's test to further investigate publication bias. Begg’s test (p = 0.373) and Egger’s test (p = 0.127) did not show significant publication bias among included studies (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4).

To assess the impact of single study outcomes on the whole results, sensitivity analysis was performed as presented (Supplementary Fig. 5). Judging from the analysis, there was no statistically significant change of overall results after removing each trial, which confirmed the reliability and rationality of our meta-analysis.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we involved 12 clinical trials and 584 patients. We investigated the efficacy and safety of ADC plus ICI in cancer patients. The main results of the pooled analyses were as follows: (1) The pooled ORR was 58% (95%CI 46%, 70%), showing a significant difference in favor of the efficacy of combination therapy. (2) Acceptable AEs, primarily related to the skin and digestive system, were observed in the study. To our knowledge, there has been so far no meta-analysis in this field. Quhal37 and Ulas38 merely compared the efficacy of ICI-based therapy without referring to ADC, and another meta-analysis compared dual ICI with ICI monotherapy39. Besides, Zhang et al. presented the first meta-analysis that evaluated efficacy and safety of ADC40.

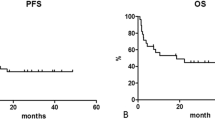

While most of the clinical studies had validated the efficacy benefits of the combination therapy, some follow-up data from late-stage clinicals didn’t show effectiveness when compared with conventional chemotherapy drugs. For example, in the KATE-2 study, there is no significant PFS difference between T-DM1 and T-DM1 plus atezolizumab in HER2-positive BC patients according to intention to treat (ITT). Nevertheless, survival benefits were observed in PD-L1-positive subgroup with a median PFS of 8.5 vs 4·1 months (HR 0.60 95%CI 0.32–1.11). Undeniably, patients failed to gain benefits from the combination therapy. It may be explained by lagging immune status and previous multiple lines of therapy. But on the other hand, the PD-L1 and HER2 positive patients showed a trend towards better survival benefits, which highlighted the importance of finding suitable ITT and treatment strategy based on gene detection. Thus, a stable selection and stratification system of patients with specific biomarkers should be established soon. It is also worth noting that NCT0444886 and NCT04740918 were expected to kindle hope for precise treatment by offering more worthy evidence.

Further analysis suggested that the improvement in patients with combination therapy may show subgroup-level differences, which correlate with information on histologic subtype and regimens. It is evident that cHL benefited most from combinations, followed by UC, PMBL, BC, NSCLC and several advanced solid tumors. Consequently, we infer that this may be related to the drug target. Tumors with high expression of targeted antigen showed better effect when treated with ADC41,42 or ICI. CD30 and PD-L1 are consistently overexpressed in patients with HL43,44 and significant inflammatory cell infiltration was detected in tumor samples. Interestingly, PMBL, a rare aggressive NHL, is also characterized by high expression of PD1 and CD30. From this we can speculate that Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab, anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, and brentuximab vedotin (BV), an anti-CD30 antibody–drug conjugate, may have synergistic activity. It has been proved that human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) is highly expressed in multiply solid tumors including BC, GC, UC and NSCLC45,46 (in order of expression), with protein overexpression, gene amplification, mutation and etc. People also found that HER2-positive oncogenesis was more likely to be correlated to higher PD-L1 and immunogenicity47, which suggested that HER2-high tumors may benefit more from ADC + ICI therapy. This may testify the ORR results of our subgroup based on histologic subtype as well. All these results emphasize the importance of immunohistochemical and pathological examinations in clinical setting. Acquiring the level and type of targeted antigen, cancer patients, especially with hematologic malignancy, may derive significant clinical efficacy. As for why hematologic malignancy could better benefit from ADC + ICI, we propose that it may be related to the more complex tumor microenvironment of solid tumors48. However, we must exercise caution in making this inference as relevant researches are still in a relatively preliminary state, and HER2-low tumor is a field remaining to be explored for combinations49. Further studies should also explore expanding the selection of ADC target from target antigens to tumor microenvironment, including the stroma and vascular system.

However, an observational multicenter real-world study demonstrated that the combination strategy exhibited promising antitumor activity in HER-2-low patients50. Also, increasing preclinical evidence indicates that ADC plus ICI therapy may hold the promise to restore the sensitivity of immunotherapy51. In order to expand the application of the combination therapy and maximize the magnitude of beneficiary group, future prospective clinical trials should be conducted to validate the value of combination strategy in negative-gene-expression patients and in advanced or metastatic cancer patients who may have developed a resistance to monotherapy. It is worth noting that a detailed stratification of patients with specific antigen level may be needed in clinical trials to meet the requirements of personalized treatment notion. Further studies that investigate the mechanism of resistance of ADC and ICI monotherapy may also help promote the development of new subtypes.

As for the subgroup analysis based on regimens, since pairing ADC with ICI is a relatively new strategy, and many clinical trials exploring this dynamic field are still ongoing or in phase I/II stages, exaggerated efficacy evaluation and data insufficiency should be considered when comparing with the different combinations. In our study, both BV + Nivo and BV + Pembro used for HM seemed to provide more ORR benefits than the other arms, which could be explained by heterogeneity caused by tumor types mentioned above. When comparing the efficacy between BV + Nivo and BV + Pembro, we could not conclude which combination was better, given that both Pembro and Nivo target PD-1 inhibitors whereas the totality of efficacy data was not uniformly reported. Moreover, ongoing clinical trials on combinations of BV + PD-1 inhibitor, such as BV + Ipilimumab (NCT01896999), may also contribute to the selection and formulation of treatment plan based on biomarker-driven rationale. Besides, we found that EV (targeting Nectin-4) + Pembro could benefit UC patients more, compared with SG (targeting Trop-2) + Pembro. However, we should interpret these data cautiously in case other factors interfere with these results. For example, the differences in the baseline characteristics for patients in SG group experienced previous more than third-line therapy while patients in EV group didn't received therapy for locally advanced or metastatic UC. As for T-DM1 + Atezo therapy, the survival benefit of BC patient in the combination arm failed to show significant improvement when compared with the control arm. Therefore, further evaluation was still needed before the evidence was translated into reliable survival outcomes. As for other treatment schemes, the data of relevant studies are still needed to support clear comparative judgment. Anyway, as the selectivity and accessibility of ADC plus ICI demonstrated a biomarker-based rationale that was associated with efficacy of combinations, it is important to recognize that inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity should be fully considered52. To achieve more satisfactory risk–benefit profiles, new strategies for optimizing combinations to maximize the advantages of them are necessary.

As for safety analysis, emerging combinations are seen as a game-changer when the efficacy of monotherapy is limited, but it can act as a double-edged sword if the combinations induce more observed AEs. The irAEs identified in our study were mainly digestive and skin problems, and no severe AEs were spotted. In general, the toxicity of ADC therapy is mainly related to the cytotoxic drugs carried, including hematotoxicity, neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity and so on53, with regards to dosing, drug design, or off-target binding54. Besides, the toxicity of ICI may have delayed onset and prolonged duration, ranging from mild skin diseases to severe gastrointestinal tract reactions and hypoalbuminemia, and even life-threatening myocarditis, chiefly affecting skin, gastrointestinal, endocrine, lung and muscle tissue55,56,57. In this meta-analysis, we observed a significantly increased risk or progression in ICI-treated patients with hypoalbuminemia. Fortunately, the irAEs identified in our study were mainly digestive and skin problems, and no severe AEs or significant additive toxicity were spotted. Even so, as the superposition of these two toxicities may offset the potential therapeutic benefits and undermine the treatment compliance, a systematic prevention and intervention method is quite necessary. Firstly, advanced assessment for patients’ physical condition is essential, especially for those at high risk. Secondly, several variable ADC formats emerged, such as bispecific ADCs, probody-drug conjugates, immune-stimulating ADCs, protein-degrader ADCs and dual-drug ADCs, offering unique capabilities for tackling current challenges. Thus, it is important for clinicians to decide which type of ADC can achieve optimal efficacy while having an acceptable incidence of adverse effects. Thirdly, clinicians are supposed to adopt an appropriate dosing strategy to achieve the optimal efficacy and safety goal. Moreover, since ICI tends to have a delayed and durable toxicity even in the combination therapy, comprehensive surveillance should be ensured in the whole process of the medication58. Fortunately, the associated toxicity of ICIs is mediated by the activation of the immune system and is dose-independent. This allows for personalized treatment plans based on individual patient responses rather than standardized dosing, potentially improving overall treatment outcomes58. Additionally, future researches should be conducted in order to assess the efficacy-AEs association and help clinicians decide whether to interrupt drugs, reduce dose, change other drugs, or adopt symptomatic treatment strategy, ensuring optimal survival benefits for patients. And a clear guidelines or consensus for management of any types of adverse reactions caused by combination strategy in clinical practice is in urgent need. Once the AEs happened, clinical nursing, temporary dose interruption and/or dose reduction should be considered.

It is worth noting that the examination of distinct payloads in ADC warrants attention, particularly regarding the observed variations in toxicity and efficacy profiles. A thorough exploration of the toxicity profiles associated with diverse payloads allows for a nuanced understanding of the safety landscape. By identifying any patterns or trends in the types and severity of adverse effects, the study can offer valuable information for clinicians and researchers alike. Also, development in the specificity and efficacy of drug delivery of ADC may further improve this synergistic mechanism and reduce the potential toxicities.

The following limitations merit consideration. For a lack of placebo arm, the efficacy of combinations may be exaggerated, and further control groups are in demand to minimize the placebo effect. As ORR is used as the outcome indicator, confirming the pharmacodynamic benefit of the combinations, future studies should be carried out in order to further confirm the survival benefit. Furthermore, in our meta-analysis, the tumor type, disease progression and different drug mechanism may have biased the results. Although we have performed subgroup analysis to reduce this bias, some partial trials were still unable to be reassessed because of limited sample data. Last but not least, although the reasons for drug efficacy and specific benefit from specific cancer type have been evaluated from antigen and target levels, our study still remained on the interpretation of phenomena, and further mechanism researches are needed.

Methods

Search strategy

Two investigators independently searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, etc. from inception to Jun. 5, 2024. All retrievals were implemented using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free words, and the complete search string was introduced in Supplementary Methods 1, 2, 3. Additional records identified through other sources including ClinicalTrials.gov, American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), books and the references of reviews were also checked to make sure that no eligible articles were omitted. The search term was ‘Neoplasms’ AND ‘Antibody–Drug Conjugates’ AND ‘Immune checkpoint inhibitors’ AND ‘Clinical trials’ with no restriction of countries, region, race, and language. The protocol of our study has been registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023375601).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) clinical studies including randomized control trials and single-arm studies; (2) patients have received ADC + ICI. (3) studies including patients confirmed with tumor; (4) studies reporting ORR with 95% CI.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) animal or in vitro test; (2) article type: letters, review, meta-analysis, comment, case report, conference abstract, editorials, expert opinions, etc. (3) studies report AEs without ORR; two investigators lay down the inclusion and exclusion criterion and a third reviewer assisted in reaching consensus when necessary.

Quality assessment

With the risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool, two investigators independently assessed the quality of the included studies. Each study was defined as ‘low risk’, ‘moderate risk’, ‘serious risk’, ‘critical risk’ or ‘no information’ respectively by considering the following characteristics covering bias due to confounding; bias in selection of study participants; bias in exposure measurement; bias due to misclassification of exposure during follow-up; bias due to missing data; bias in measurement of outcomes; and bias in selection of reported results. And GRADE methodology was conducted in order to assess the overall quality of evidence.

Data extraction

Two investigators independently extracted data from included studies with PRISMA, and any inconsistencies were resolved by consensus with a third investigator. The following characteristic information of the included studies was recorded: (1) Study characteristics: first author, publication time, follow-up, cancer type, phase line, regimen, sample size, age range; (2) Study outcomes: ratio of ORR, partial response (PR), complete response (CR), stable disease (SD), progressive disease (PD), AEs; To make sure that no information was omitted, we also checked supplement materials of each clinical trial.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of study outcomes were performed by RevMan 5.3 and pooled as forest plots by STATA 15. The effect size of all pooled results was represented by 95% CI with an upper limit and a lower limit. Chi-square Q test and I2 statistic was used to detect statistical heterogeneity. If heterogeneous was observed between studies (p < 0.10, I2 > 50%), the random‐effects model would be used for combined analysis. Otherwise, fixed-effects model was used for pooled results. Furthermore, subgroup analysis was implemented to identify the factors contributing risk of bias. We also conducted the sensitivity analysis by sequential exclusion of included individual trial. Funnel plots, Begg’s and Egger’s tests were also used to examine potential publication bias.

Conclusions

In general, the combination of ADC and ICI therapeutics might be a promising treatment option. This single-arm meta-analysis suggested that both regimen and tumor type had great impact on treatment effect, indicating that selection of regimen and tumor type of patients are important. Meanwhile, potential toxicity on skin and digestive system were also observed in patients, suggesting management of adverse events is of vital importance.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADC:

-

Antibody–drug conjugate

- AEs:

-

Adverse effects

- ASCO:

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- Atezo:

-

Atezolizumab

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- BV:

-

Brentuximab vedotin

- cHL:

-

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- CR:

-

Complete response

- Dato-DXd:

-

Datopotamab deruxtecan

- ES:

-

Effect size

- ESMO:

-

European Society for Medical Oncology

- EV:

-

Enfortumab vedotin

- GC:

-

Gastric cancer

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor 2

- HPD:

-

Hyperprogressive disease

- ICI:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- ITT:

-

Intention to treat

- mAb:

-

Monoclonal antibody

- NA:

-

Not available

- Nivo:

-

Nivolumab

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- NSCLC:

-

Non small-cell lung cancer

- ORR:

-

Overall response rate

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- Pembro:

-

Pembrolizumab

- PR:

-

Partial response

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- SG:

-

Sacituzumab govitecan

- T-DM1:

-

Trastuzumab emtansine

- UC:

-

Urothelial cancer

References

Sung, H. et al. global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Goulet, D. R. & Atkins, W. M. Considerations for the design of antibody-based therapeutics. J. Pharm. Sci. 109, 74–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xphs.2019.05.031 (2020).

Fu, Z. et al. Antibody drug conjugate: The “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00947-7 (2022).

Thomas, A., Teicher, B. A. & Hassan, R. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Lancet Oncol. 17, e254–e262. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30030-4 (2016).

Tsuchikama, K. et al. Exploring the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 203–223. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00850-2 (2024).

Corti, C. et al. Antibody-drug conjugates for the treatment of breast cancer. Cancers https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13122898 (2021).

Padua, T. C. et al. Efficacy and toxicity of antibody-drug conjugates in the treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer: A scoping review. Urol. Oncol. 40, 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2022.07.006 (2022).

Ungaro, A. et al. Antibody-drug conjugates in urothelial carcinoma: A new therapeutic opportunity moves from bench to bedside. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11050803 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. HER2-targeted therapies in gastric cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1876, 188549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188549 (2021).

Rosellini, M. et al. Treating prostate cancer by antibody-drug conjugates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041551 (2021).

Samantasinghar, A. et al. A comprehensive review of key factors affecting the efficacy of antibody drug conjugate. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114408 (2023).

Bagchi, S., Yuan, R. & Engleman, E. G. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: Clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 16, 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020-042741 (2021).

Retifanlimab, K. C. First approval. Drugs 83, 731–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-023-01884-7 (2023).

Kong, X. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Cancer Biol. Med. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2024.0055 (2024).

Hayashi, H. & Nakagawa, K. Combination therapy with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors for cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 818–830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-019-01548-1 (2020).

Li, B., Chan, H. L. & Chen, P. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Basics and challenges. Curr. Med. Chem. 26, 3009–3025. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867324666170804143706 (2019).

Morad, G. et al. Hallmarks of response, resistance, and toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade. Cell 184, 5309–5337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.020 (2021).

Abu-Yousif, A. O. et al. Preclinical antitumor activity and biodistribution of a novel anti-GCC antibody-drug conjugate in patient-derived xenografts. Mol. Cancer Ther. 19, 2079–2088. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-19-1102 (2020).

Cassetta, L. & Pollard, J. W. Targeting macrophages: Therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.169 (2018).

de Bono, J. S. et al. Tisotumab vedotin in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumours (InnovaTV 201): A first-in-human, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20, 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30859-3 (2019).

Bauzon, M. et al. Maytansine-bearing antibody-drug conjugates induce in vitro hallmarks of immunogenic cell death selectively in antigen-positive target cells. Oncoimmunology 8, e1565859. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2019.1565859 (2019).

Müller, P. et al. Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) renders HER2+ breast cancer highly susceptible to CTLA-4/PD-1 blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 315ra188. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4925 (2015).

Kepp, O., Zitvogel, L. & Kroemer, G. Clinical evidence that immunogenic cell death sensitizes to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Oncoimmunology 8, e1637188. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2019.1637188 (2019).

Iwata, T. N. et al. [Fam-] trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201a)-induced antitumor immunity is facilitated by the anti-CTLA-4 antibody in a mouse model. PLoS ONE 14, e0222280. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222280 (2019).

Gerber, H. P. et al. Combining antibody-drug conjugates and immune-mediated cancer therapy: What to expect?. Biochem. Pharmacol. 102, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2015.12.008 (2016).

Rizzo, A. et al. Ladiratuzumab vedotin for metastatic triple negative cancer: Preliminary results, key challenges, and clinical potential. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 31, 495–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2022.2042252 (2022).

Grivas, P. et al. TROPHY-U-01 Cohort 3: Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) in combination with pembrolizumab (Pembro) in patients (pts) with metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC) who progressed after platinum (PLT)-based regimens. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 434–434. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2022.40.6_suppl.434 (2022).

Advani, R. H. et al. Brentuximab vedotin in combination with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: 3-year study results. Blood 138, 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020009178 (2021).

Zinzani, P. L. et al. Nivolumab combined with brentuximab vedotin (BV) for relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (R/R PMBL): Efficacy and safety results from the phase 2 CheckMate 436 study. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 19, S303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2019.07.262 (2019).

Emens, L. A. et al. Trastuzumab emtansine plus atezolizumab versus trastuzumab emtansine plus placebo in previously treated, HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (KATE2): A phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1283–1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30465-4 (2020).

Cheson, B. D. et al. Brentuximab vedotin plus nivolumab as first-line therapy in older or chemotherapy-ineligible patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (ACCRU): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 7, e808–e815. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3026(20)30275-1 (2020).

Rottey, S. et al. Phase I/IIa trial of BMS-986148, an anti-mesothelin antibody-drug conjugate, alone or in combination with nivolumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-21-1181 (2022).

Hoimes, C. J. et al. Enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab in previously untreated advanced urothelial cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.01643 (2022).

Massaro, F. et al. Brentuximab vedotin and pembrolizumab combination in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: A single-centre retrospective analysis. Cancers https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14040982 (2022).

Rosenberg, J. E. et al. LBA73 Study EV-103 Cohort K: Antitumor activity of enfortumab vedotin (EV) monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab (P) in previously untreated cisplatin-ineligible patients (pts) with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (la/mUC). Ann. Oncol. 33, S1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.08.079 (2022).

Vergote, I. et al. Tisotumab vedotin in combination with carboplatin, pembrolizumab, or bevacizumab in recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer: Results from the innovaTV 205/GOG-3024/ENGOT-cx8 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 5536–5549. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.23.00720 (2023).

Quhal, F. et al. First-line immunotherapy-based combinations for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 4, 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euo.2021.03.001 (2021).

Ulas, E. B. et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review. ESMO Open 6, 100244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100244 (2021).

Ma, X. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) combination therapy compared to monotherapy in advanced solid cancer: A systematic review. J. Cancer 12, 1318–1333. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.49174 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Is antibody-drug conjugate a rising star for clinical treatment of solid tumors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 177, 103758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103758 (2022).

Bussing, D. et al. Quantitative evaluation of the effect of antigen expression level on antibody-drug conjugate exposure in solid tumor. AAPS J. 23, 56. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-021-00584-y (2021).

Lazzerini, L. et al. Favorable therapeutic response after anti-mesothelin antibody-drug conjugate treatment requires high expression of mesothelin in tumor cells. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 302, 1255–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05734-9 (2020).

Andrade-Gonzalez, X. & Ansell, S. M. Novel therapies in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 22, 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-021-00840-5 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Advances in CD30- and PD-1-targeted therapies for classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 11, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-018-0601-9 (2018).

Indini, A., Rijavec, E. & Grossi, F. Trastuzumab deruxtecan: Changing the destiny of HER2 expressing solid tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094774 (2021).

Vranić, S., Bešlija, S. & Gatalica, Z. Targeting HER2 expression in cancer: New drugs and new indications. Bosn J. Basic Med. Sci. 21, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2020.4908 (2021).

Chen, Y. L. et al. A bispecific antibody targeting HER2 and PD-L1 inhibits tumor growth with superior efficacy. J. Biol. Chem. 297, 101420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101420 (2021).

Gohil, S. H. et al. Applying high-dimensional single-cell technologies to the analysis of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-00449-x (2021).

Criscitiello, C., Morganti, S. & Curigliano, G. Antibody-drug conjugates in solid tumors: A look into novel targets. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01035-z (2021).

Nie, C. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors enhanced the antitumor efficacy of disitamab vedotin for patients with HER2-positive or HER2-low advanced or metastatic gastric cancer: A multicenter real-world study. BMC Cancer 23, 1239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11735-z (2023).

Koopman, L. A. et al. Enapotamab vedotin, an AXL-specific antibody-drug conjugate, shows preclinical antitumor activity in non-small cell lung cancer. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.128199 (2019).

Nadkarni, D. V. et al. Impact of drug conjugation and loading on target antigen binding and cytotoxicity in cysteine antibody-drug conjugates. Mol. Pharm. 18, 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00873 (2021).

Zhu, Y. et al. Treatment-related adverse events of antibody-drug conjugates in clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 129, 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34507 (2023).

Masters, J. C. et al. Clinical toxicity of antibody drug conjugates: A meta-analysis of payloads. Investig. New Drugs 36, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-017-0520-6 (2018).

Martins, F. et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 563–580. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-019-0218-0 (2019).

Ramos-Casals, M. et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 6, 38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6 (2020).

Guven, D. C. et al. The association between albumin levels and survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 1039121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.1039121 (2022).

Dall’Olio, F. G. et al. Immortal time bias in the association between toxicity and response for immune checkpoint inhibitors: A meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 13, 257–270. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2020-0179 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the great help from the Medical Research Center, Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University.

Funding

This work was founded by the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by China Association of Chinese Medicine [2021-QNRC2-B13]; the Zhejiang Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Scientific Research Fund Project [2023ZR095, 2024ZR022]; the Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province [2024KY1226]. The Construction Fund of Medical Key Disciplines of Hangzhou, China [No. OO20200385].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Leitao Sun, Ning Ren and Jieru Yu contributed to the design and conception of the study. Leyin Zhang, Yici Yan and Yixin Chen carried out the collection and processing of data. Leyin Zhang, Yangyang Gao and Yixin Chen performed the data analysis, interpretation, and statistical analysis. Leyin Zhang and Yici Yan wrote the manuscript. Ning Ren and Jieru Yu revised the manuscript, then Leitao Sun gave the final approval of manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Yan, Y., Gao, Y. et al. Antibody–drug conjugates and immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 14, 22357 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68311-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68311-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

LGALS3BP antibody-drug conjugate enhances tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and synergizes with immunotherapy to restrain neuroblastoma growth

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)

-

Mechanisms of resistance to trastuzumab deruxtecan in breast cancer elucidated by multi-omic molecular profiling

npj Breast Cancer (2025)