Abstract

Network slicing is crucial to the 5G architecture because it enables the virtualization of network resources into a logical network. Network slices are created, isolated, and managed using software-defined networking (SDN) and network function virtualization (NFV). The virtual network function (VNF) manager must devise strategies for all stages of network slicing to ensure optimal allocation of physical infrastructure (PI) resources to high-acceptance virtual service requests (VSRs). This paper investigates two independent network slicing frameworks named as dual-slice isolation and management strategy (D-SIMS) and recommends the best of the two based on performance measurements. D-SIMS places VNFs for network slicing using self-sustained resource reservation (SSRR) and master-sliced resource reservation (MSRR), with some flexibility for the VNF manager to choose between them based on the degree to which the underlying physical infrastructure has been sliced. The present research work consists of two phases: the first deals with the creation of slices, and the second with determining the most efficient way to distribute resources among them. A deep neural network (DNN) technique is used in the first stage to generate slices for both PI and VSR. Then, in the second stage, we propose D-SIMS for resource allocation, which uses both the fuzzy-PROMETHEE method for node mapping and Dijkstra’s algorithm for link mapping. During the slice creation phase, the proposed DNN training method’s classification performance is evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score measures. To assess the success of resource allocation, metrics such as acceptance rate and resource effectiveness are used. The performance benefit is investigated under various network conditions and VSRs. Finally, to demonstrate the importance of the proposed work, we compare the simulation results to those in the academic literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, fifth-generation (5G) communication networks have changed the ICT landscape. The 5G mobile network aims to support multiple vertical markets efficiently and flexibly, such as ultra-reliable low latency communications (uRLLC), enhanced mobile broadband (eMBB), and massive machine type communications (mMTC)1. As shown in Fig. 1, network slicing is an effective method that can be used to learn more about how resources could be sliced in order to meet a wide range of customers’ needs2. Most research on network slicing in the 5G era has been on either radio access network (RAN) slicing or core network (CN) slicing3. Research has been carried out on virtualizing and softwarizing the radio resources for RAN slicing4, while studies known as end-to-end (E2E) network slicing investigates where Virtual Network Functions (VNFs) should be located with respect to the underlying actual infrastructure so that individual slices can operate autonomously5,6. A study was carried out on the creation of interfaces and protocols for inter-slice communication between RAN and CN7.

Isolating network slices from one another is an essential requirement for network slicing. This will eventually guarantee that only the VNFs required to run the intended applications are present in each slice. Therefore, related efforts are typically focused on optimizing the deployment of several autonomous virtual networks8. For the 5G network as a whole to be able to provide the needed network slice services, each instance of the slice must have all of the relevant VNFs. 5G slicing enables for different degrees of isolation that share network services or functions across numerous slice instances. In the course of the last few decades, a number of different algorithms for embedding VNs have been developed. According to the type of optimization method employed, these VN embedding algorithms can be classified in the cases of heuristic algorithms9,10,11, meta-heuristic algorithms12,13, and accurate algorithms14,15. During the node mapping stage, heuristic algorithms primarily rely on node importance ranking techniques to rank the corresponding importance of the substrate nodes and virtual nodes. In both cases, link mapping for the virtual nodes is handled using the K-shortest path technique. Also, some learning-based algorithms are rarely used in the literature when it comes to service provisioning16 or the creation of slices17.

As is commonly known, network slicing involves three main components: slice creation, isolation, and management. Many network slicing orchestration frameworks are only focused on a specific network slicing function. It is widely acknowledged that the orchestration framework must still be developed in order to meet the requirements of delivering each service for all three network slicing responsibilities. Furthermore, when VNF managers use a single framework that provides services in all three aspects of slicing, they gain a competitive advantage in providing higher-quality services to their customers. In order to address the issues identified in previous studies, this article provides an orchestration framework that considers all three steps of the network slicing process. The following is a list of the most important contributions that our work has made:

-

To the greatest extent of our knowledge, this is the first work to provide a full package for 5G network slicing, covering the three main aspects of network slicing: slice creation, isolation, and management. Coordination between the three components is effectively handled by properly defining the VNF at each component.

-

To apply a deep neural network (DNN) training approach for slice creation, the performance dataset is prepared for learning based on the realistic characteristics of diverse use cases.

-

To model a slice-aware network orchestration framework for optimal resource allocation based on dual-slice isolation and management strategy (D-SIMS), namely self-sustained resource reservation (SSRR) and master-sliced resource reservation (MSRR). The strategy selection is made based on the degree to which the underlying physical infrastructure has been sliced. Both of these strategies are capable of handling all three stages of the execution process, which are as follows: (1) slice creation by deep neural network (SC-DNN), (2) slice isolation by hybrid fuzzy-PROMETHEE (SI-FP), and (3) slice management by addressing four responsibilities (SM-4R).

-

To prepare strategy specific VNF for addressing four major responsibilities of slice management, such as request report generation (RRG), dynamic resource recovery (DRR), inner-resource sharing (IRS), and priority resource allocation (PRA).

-

To make a more informed recommendation regarding the optimal network slicing strategy and PI virtualization. This paper conducts an in-depth examination of two distinct strategies and evaluates them under different physical infrastructure conditions and VSR settings. The optimal strategy for a given system is then adopted.

The literature review for slice creation, isolation and management are carried out independently due to the fact that this work builds the orchestration framework for addressing all three aspects of network slicing.

Slice creation strategies

Machine learning (ML) is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) in which a machine or system can learn on its own by analyzing the results of previous observations. Growing amounts of data and increased competition have led to the widespread adoption of ML in a wide range of industries and sectors18,19. 5G networks are becoming more complicated as the number of newly connected devices and types of services has increased exponentially. ML can be considered for automating various network functionalities such as slice creation, deployment, management, monitoring, fault detection, and security20,21. With a focus on ML-based slice creation, a lot of research has been done to show how the ML model can be used with the 5G network. Slicing a 5G network allows for adaptable service delivery to specific use cases. In22, an effective slice formation mechanism used that supports Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) connected to 5G and ensures resource allocation by modifying the inter and intra-slice allocation methods. Random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and decision tree (DT) have been used in23 to select the best suitable slice in the physical network. According to the results of the study, using RF and KNN to create slices yields more accurate results than the SVM and DT methods. In addition to that, this strategy achieved a high quality of service and service level agreement. In24, RF shows greater performance while maintaining a high level of accuracy in the classification operation to distribute the slices for the network traffic. In25 efficient network slicing, ML and hybrid learning models have been used. Both of them significantly improve the network’s performance. A deep belief network (DBN) method was used in26 for slice classification. The slices were classified according to eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC with regard to the use cases. DNN has been used to build slices that are more efficient and accurate. It uses KPIs to analyze the network traffic and use cases. This method aims to select slices and for slice prediction with resource allocation, slice management, and traffic management in case of network failure.

Slice isolation and management strategies

The authors of27 developed two node mapping methods with the help of the sequential selection principle and auxiliary graphs, which turned the issue into a traditional graph theory problem. In28, an actor-critic Reinforcement Learning (RL) model uses five ideal graph characteristics to create the issue environment, which is then changed using a ranking mechanism. For the purpose of virtual network embedding, the network topology attribute and network resource-considered algorithm (VNE-NTANRC) was suggested in29. Before embedding any particular VN, the VNE-NTANRC algorithm uses a novel way to rank nodes to determine the order in which all of the substrate and virtual nodes should be ranked. The innovative method for ranking nodes takes into account a total of five significant network topology aspects as well as global network resources. On the basis of the limitations of computational, network, and storage resources30,31, proposed two fundamental VNE techniques, namely node ranking metric for virtual network embedding (NRM-VNE) and resource consumption ratio for virtual network embedding (RCR-VNE). Authors of32 suggested a heuristic technique known as information-centric networking-network slice determination and embedding to address challenges associated with network embedding in large-scale networks. In33, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based modeling of network slice traffic demands for resource management to tackle the issues of mobility management and non-uniform slice deployment across an identified region. The primary value of the proposed algorithm is that it solves the problem without requiring any background information about the topology of the network or the availability of its resources. In order to distribute the connections and nodes over a network, methods including PROMETHEE-II and SLE are employed34. The PROMETHEE-II technique considers a selection of node features, and the SLE method is suggested to collect every possible links for network service request nodes in order to guarantee the shortest path of the network service request. The authors of35 used an integer linear program (ILP) approach to solve a 5G E2E sharable-VNFs-based multiple linked VNE problem (SVM-VNE). The unique topological features of the 5G network were used to categorize VNFs as either sharable or non-sharable and to determine how much of a difference there would be in the resources needed to support each. By taking advantage of VNFs’ inherent capacity for sharing, the suggested work is able to reduce the amount of material resources needed. In36, the authors examined several metrics for multi-dimensional mapping efficiency and rated their usefulness for heuristic and accurate network service embedding (NSE) approaches. Two heuristics and a mixed integer linear program (MILP) were suggested by the authors based on their study on optimising multidimensional NSE.

In37, optical network virtualization was implemented, adding an extra layer of complexity due to the optical networks’ unique physical characteristics. In addition to providing a user-friendly environment, this unified virtualization technology also provides an abundance of bandwidth resources. In38, the authors focused solely on the challenges of modeling resource and energy utilization for IoT applications operating in edge-cloud paradigms. For the purpose of providing a concrete example for the accurate modeling of a service chain, a smart traffic monitoring IP camera system was implemented. The authors then proposed a dynamic energy-aware service function chain (SFC) strategy for edge-to-cloud IoT applications. The goal of the article39 was to simplify the network topology by integrating data centers and optical networks effectively. This was done by utilizing the parallel transmission properties of optical fiber. The work presented a mathematical model for virtual network embedding with the support of node proximity sensing and path comprehensive evaluation. The authors of the paper40 developed a model for estimating energy consumption and created an algorithm for energy-aware virtual network migration (EA-VNM). They also developed an enhanced group VN migration algorithm to reduce the time complexity of EA-VNM to a large extent while simultaneously allowing migration to take place in parallel. The most recent contribution made by the authors was a proposal for a prioritized admission control mechanism41 for concurrent slices, which was based on an approach to infrastructure resource reservation. The reservation takes into account the dynamic nature of slice requests while also being resistant to the unpredictability of slice resource requirements.

Motivation

The most recent works associated with network slicing are compiled in Table 1, which provides a summary of the literature on network slicing components such as slice creation (SC), slice isolation (SI), and slice management (SM). The table also includes the techniques, performance measurements, and task criteria used in the solution process. In most studies, researchers have employed the same metrics for performance measurement of the strategies. Different methodologies and aspects of network slicing have been described in the various pieces of literature, leading to inconsistencies in the field. According to our research and analysis of the relevant literature, following is the summary and limitations of the aforementioned works on network slicing:

-

The majority of the works listed in the table offer approaches for slice creation [18–21], while some works focus solely on slice isolation [22–26] and others cover both slice isolation and slice management [27–33].

-

When it comes to resource allocation, the literature [27–29] focusing on slice management only offer solutions for resource recovery (RR), taking into consideration the life-time of VSRs.

-

Many previous works have allotted resources to a fixed assignment by making the assumption that every application of a VSR is one of a kind. In order to prevent unsuccessful use cases, the monitoring of the accessible resources within the other slices of data that are of a different kind has been disabled.

-

Because of the aforementioned assumption for slice isolation, almost no works have adopted the concept of inner-slicing (IS) in order to supply resources for unsuccessful use case, with the notable exception of [31]. The VNF should be defined into individual slices so as to find a way to allocate resources for different types of failed use cases on a priority basis.

-

Furthermore, priority provisioning (PP) is rarely discussed in the literature. There is no provisioning of VNF for the individual slices to make space for resources supporting priority services. It is the responsibility of the VNF in each slice to effectively manage resource contention while making allocation attempts for critical services and unsuccessful use cases.

This led us to conclude that it is important to create an orchestration framework that can handle all three aspects of network slicing. As a result, each part of network slicing is tackled with the most effective methods in the suggested framework. The foundational structure of the new work that is being proposed has been developed to address the shortcomings of the previous works. The accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score are used to evaluate the classification performance of the proposed DNN training method during the slice generation phase. Acceptance rate and resource effectiveness are two metrics used to evaluate the efficiency of resource allocation.

Paper organization

The rest of this article is organized as follows: “System model” section summarizes the proposed system model; “Mathematical background” section provides the mathematical background; “Proposed framework” section describes the proposed 5G network framework; “Simulation results” section discusses simulation results with case study; “Conclusion” section concludes the work.

System model

Physical infrastructure

A weighted undirected graph is used to describe the topological structure of the physical infrastructure (PI). The graph is represented as \(G_{P}= (N_{P},E_{P})\), where \(N_{P}\) represents a collection of PI nodes and \(E_{P}\) indicates a collection of physical links. In a graph, every node should have a CPU capacity (C), a link capacity (LC), a security level (SL), a delay rate (DR), and a jitter value (JT). As an example, the parameters of the \(i^{th}\) node of a graph is specified as a subset containing \( (C_{P}^{i}, LC_{P}^{i}, SL_{P}^{i}, DR_{P}^{i}, JT_{P}^{i}), i \in N_{P}\). Each edge in a graph is also given a subset of information about its associated nodes, denoted by \(E_{P}^{i}(BW_{P}^{ij},L_{P}^{ij})\), where \(BW_{P}^{ij}\) is the bandwidth of the link connecting node \(i\) and \(j\) in PI, \(L_{P}^{ij}\) is the length of the link connecting node \(i\) and \(j\) in PI.

Virtual service request

Each VSR needs to meet requirements for the number of nodes, CPU power, bandwidth, security, the lifespan, and types of user devices. Every VSR is modeled as an undirected graph \(G_{V}= (N_{V},E_{V})\) where \(N_{V}\) represents the nodes of the VSR and \(E_{V}\) represents the edges of the VSR. Each node of a VSR should have \( (C_{V}^{m},LC_{V}^{m},SR_{V}^{m},LT_{V}^{m},DT_{V}^{m})\), \(m\in N_{V}\) where \(C_{V}^{m},LC_{V}^{m},SR_{V}^{m},LT_{V}^{m}\) and \(DT_{V}^{m}\)are the required CPU capacity, link capacity, security requirement, life-time and device type of \(m^{th}\) node, respectively. Similarly, we can denote the bandwidth requirement for the link between nodes \(m\) and \(n\) as \(BW_{V}^{mn}\). We assume that the VSRs are received during a single transmission window42. The VSRs make use of the physical infrastructure at regular intervals in order to assign nodes and establish connections. The \(LT_{V}\) of the previous request is used to determine how the physical infrastructure’s available resources should be adjusted whenever a new VSR is received.

Mathematical background

Variables

\(\pi _{i}^{m}\) : A binary variable with a value equals 1 if the mapping of virtual network node \(m\) to physical network node \(i\) was successful, and 0 otherwise.

\(f _{ij}^{mn}\) : A binary variable whose value is 1 if the physical network path \((i,j)\) accommodates the virtual network link \((m,n)\) successfully and whose value is 0 if the link mapping is unsuccessful.

\(l^{mn}\): A variable that will indicate the shortest path available on the virtual link \((m,n)\).

Objective

Constrains

Node processing constraints

Link associated constraints

\( \hspace{4cm} \forall {i, j} \in E_{P}, \forall {m,n} \in E_{V} \)

Variable constraints

Statements: The objective function (1) seeks to minimize the cost of the D-SIMS to accommodate the virtual request nodes. The (2) constraint ensures that each PI node \( i \in N_{P}\) has enough CPU capacity to meet the needs of each virtual node \(m \in N_{V}\). The (3) constraint guarantees that the requested link capacity of a virtual node \(m \in N_{V}\) can be met by the link capacity of a PI node \( i \in N_{P}\). Security level of the virtual node \(m \in N_{V}\) can be satisfied by the security measures of the PI node \( i \in N_{P}\), according to constraint (4). The bandwidth of the PI node \(i \in N_{P}\) must meet the bandwidth requirements of the virtual node \(m \in N_{V}\) according to constraint (5). The connectivity constraint is represented by Eq. (6). Mapping virtual links \((m,n)\) to their physical links \((i,j)\) is carried out in link mapping stage. If the outflow from the source PI node \(i \in N_{P}\) is 1, but the inflow from node \(j \in N_{P}\) is 0, the result is \({\sum _{{(i,j)} \in E_{P}} f_{ij} ^{mn}} - {\sum _{{(j,i)} \in E_{P}} f_{ji}^{mn}} = 1 \); in the destination PI node \(i \in N_{P}\), the outflow value is 0, while the inflow value is 1, then \({\sum _{{(i,j)} \in E_{P}} f_{ij} ^{mn}} - {\sum _{{(j,i)} \in E_{P}} f_{ji}^{mn}} = -1 \); in the other PI node the outflow and inflow value is 1, then \({\sum _{{(i,j)} \in E_{P}} f_{ij} ^{mn}} - {\sum _{{(j,i)} \in E_{P}} f_{ji}^{mn}} = 0 \). Constraints (7) and (8) ensure that a PI node can only host a virtual node from the same VSR, and that a virtual node can only be mapped onto a PI node. \( \pi _{i}^{m} \) and \(f_{mn} ^{ij} \) are assured to be two binary variables according to constrains (9) and (10).

Performance metrics

We define a set of performance criteria to evaluate the proposed techniques43, which include the classification accuracy (A), precision (P), recall (R), F1 score (FS), resource efficiency (RE), resource utilization (\(CPU_{utilized}\) and \(BW_{utilized}\)) and acceptance ratio (AR).

Classification

Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score metrics are used to evaluate the classification performance of the predicted model. The metrics are calculated with the help of the following four indicators: (1) True positives (\(TP\)), (2) False positives (\(FP\)), (3) False negatives (\(FN\)), (4) True negatives (\(TN\))44. The process of determining a classification accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score is denoted as,

Resource utilization

Total CPU capacity, link capacity and bandwidth can be computed by summing the utilized quantities of each successful VSR (SV). The total utilized CPU capacity and bandwidth of each successful VSR are stored in \({TC_k}\), \({TLC_k}\) and \({TBW_k}\), respectively, after the VSR has been successfully provisioned in PI.

Resource efficiency

Resource efficiency can be measured using the revenue-to-cost ratio. The total of the node capacity, link capacity and link bandwidth needs of an VSR can be used to calculate the revenues from adopting an VSR. A network’s overall cost is equal to the total cost of its node capacity, link capacity, and link bandwidth. Resource efficiency is represented as,

Modified the below equation

where \(L_{SV}\) represents the mapping length of each VSR’s shortest path which has been retrieved at the end of link provisioning.

Acceptance ratio

To calculate this metric, we divide the number of successful VSRs by the total number of VSRs that occurred within the chosen transmission time interval \(T _{max}\).

where \(TV\) denotes total VSR.

Proposed framework

For the purpose of network slicing, the proposed framework suggests two different alternative strategies, which are referred to as SSRR and MSRR of D-SIMS. The VNF manager chooses one of these strategies based on the manner in which the PI is sliced. When the PI is virtualized as three slices, the VNF manager chooses the SSRR strategy. On the other hand, the MSRR strategy is chosen when the PI is virtualized as four slices. As can be seen in Fig. 2, both approaches are broken down into the same set of three distinct phases, which are labeled as slice creation, isolation, and management. Each of these phases is in charge of its own specific group of responsibilities, and together they make up the overall process. However, the architecture’s phases are interdependent and must be carried out in sequence. In the slice creation phase, the slices are generated for the PI and received by the VSR, which gets the initial state of PI as the input at \({t}=0\) and gets the information about updated states of PI from the slice management phase while getting the next VSR. The created slices of PI and VSR are transferred to the slice isolation phase, where a VNF placement method is applied to allocate resources. The slice management phase is commenced when any of the VSRs fails, where the effective management approaches are applied to make unsuccessful VSRs successful. This phase also incorporates resource sharing for slice management after combining the results of the previous two phases. The following subsections describe the processes involved in each phase of the strategies.

DNN for slice creation

DNN is a kind of ML in which the system makes use of several layers of nodes to extract higher-level functions from lower-level data. The construction of DNN is built on layer connections via nodes known as neurons, analogous to the biological neurons in the brain. DNN has three layers, namely the input layer, two or more hidden layers, and the output layer. As an input, the KPI of the user devices is provided, and for each of the two hidden layers, 15 neurons are taken into consideration. An associated connection weight, \(w_{j}\), is assigned to each interconnection between two neurons. This weight is fitted throughout the learning phase of the process. In order to determine its output, each neuron first computes a weighted sum of its inputs. In addition, the bias value is added along with the cumulative input. Weights are optimized with the assistance of a variety of methods, including stochastic gradient descent (SGD), limited-memory broyden-fletcher goldfarh shanno (LBFGS), and adaptive moment estimation (ADAM). In order to get the intended outcome for the neuron, the activation function applies itself to the cumulative input value that is generated via the additive function. In this situation, the sigmoid activation function, which is a continuous, nonlinear, and straightforward derivative function, is utilized.

The output neurons of the hidden layers are calculated using,

where \(x_{j}\) is the KPIs of node, b is the bias, and \(w_{j}\) is the weight of connection links. The output of the \(i^{th}\) node in the hidden layer is,

where \(f\) is the sigmoid activation function. Final output of all neurons in the output layer \(y ^{\wedge }\) is denoted as,

Due to differences in how they virtualize the underlying physical infrastructure, the proposed work creates slices independently for each of the two D-SIMS. The SSRR strategy has been sliced into three parts: eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC, while the MSRR strategy has been sliced into four parts: eMBB, mMTC, uRLLC, and a master slice. A performance dataset with input and label is prepared independently for each approach. Slices in SSRR are made using each node’s KPIs. Since the master slice nodes in MSRR must be shared across all possible user requests during critical conditions, the rules for these nodes are designed to preserve those with the highest KPI values. The remaining PI nodes are divided into three groups based on their KPI values. Classification is performed using deep neural network. Accuracy is calculated to measure the performance of classification. Based on classification, three groups are formed in SSRR and four groups in case of MSRR.

Slice isolation of D-SIMS

We comprehend that allocating resources to the VSR nodes in the PI involves two sequential operations, namely, node provisioning and link provisioning. To ensure the throughput, CPU capacity, and VSR security service level agreements (SLAs) are met, it is important to validate the allotted nodes and links. Additionally, the distribution of resources should maximize revenue and efficient resource utilization. In order to meet those requirements, this work proposes a hybrid fuzzy-PROMETHEE method to perform node provisioning and Dijkstra’s algorithm for link provisioning.

Node mapping through fuzzy-PROMETHEE

Most studies have found that feature extraction from individual nodes is the most effective way for analysing network nodes. In order to determine a node’s ranking, we take into account factors like its CPU capacity (23), degree (24), bandwidth (25), and closeness centrality (26).

where \(C^{i}\) is the CPU capacity of node \(i\) in the network, \(E^{ij}\) is a binary value that is 1 if nodes \(i\) and \(j\) are connected and else 0, Shortest path length between nodes \(i\) and \(j\) is denoted by \(L^{i,j}\) where \(BW^{ij}\) is the bandwidth of the connection between nodes \(i\) and \(j\).

These four variables have different relative importance’s and need be normalised before being ranked. In order to meet this demand, a min-max scalar based on fuzzy rules was developed for each of the four parameters. When applied to the parameters, the common membership function can be written as,

Where, \(Y_{i}\) refers to any parameter of a node ’\(i\)’. The lower and upper bounds (\(Y_{min}\) and \(Y_{max}\)) of the respective node parameters are identified from the network information. For instance, when calculating a node’s bandwidth parameter (\(BN_{i}\)), the value is calculated by first finding by the node with the lowest available bandwidth in the network \(BN_{min}\), and then the value is finding the node with the largest available bandwidth \(BN_{max}\). The network characteristics are also used to derive minimum and maximum values for the other node properties. After computing the membership values of every node in both the PI and VSR networks, the PROMETHEE-based multi-criteria decision making45 is immediately put into effect, and the ranking of the nodes is done. In this approach, the parameters of each node are considered separately, based on their interests and individual preferences. The steps of the PROMETHEE-II method are as follows:

Step 1: Preparation of evaluation table. Each node in the evaluation table has its fuzzy membership values saved in the evaluation Table 2. Assumed here \(N=[n_{1}, n_{2},...,n_{l}]\) and \(X=[X_{CN},X_{DN},X_{BN},X_{LN}]\) are the sets of nodes and membership values, respectively.

Step 2: Preparation of preference function. In a network, every node is compared to every other node in the network using a pairwise comparison for every parameter in the network. For example, the pairwise comparison of node degree parameter is done by,

Step 3: Building a global preference index.

where \(w_k\) is an assumed nonzero weight function of component \(k\) and the total weights add up to 1.

Step 4: Outranking flows, all positive and negative, are computed. Calculations are performed using the following two factors in order to determine the location of each node in relation to all of the other nodes.

where \(\phi ^+ (i)\) is obtained by ranking nodes by the absolute value of the positive flow to each one and \(\phi ^- (i)\) is determined by ranking the nodes by the absolute value of the negative flow to each one.

Step 5: Determination of net flow.

The most value of \(\phi (i)\) has been considered as the best node in the node ranking (NR). Algorithm 1 provides a step-by-step breakdown of the hybrid fuzzy-PROMETHEE46 procedure applied for mapping nodes. The algorithm checks for the violation of the constraint while it is attempting to map nodes. However, node mapping is only attempted if the constraints are satisfied. At the end of execution, the algorithm returns the nodes that were allocated in PI for VSR. This algorithm is carried out each time a new VSR is received for the purpose of node provisioning.

Link mapping strategy

The primary objective of this strategy is to locate the shortest path that the VSR nodes in the physical infrastructure can take to reach one another. When it comes to VSR, it is abundantly clear that there are situations in which the shortest and most direct route is not the one that should be taken. Under certain conditions, a connection on the shortest route that has been chosen can be linked to the VSRs that have already been provided. Due to this, it is absolutely necessary to find all of the connections between VSR nodes and then put them in Dijkstra’s shortest path array (DSPA)47 in a way that doesn’t go down in terms of the total length of the individual paths that connect each node. This array has the potential to be utilized in the process of establishing connections for VSRs. The shortest paths will likely be referred to in order as they are built during the process of establishing connections. When no links are being provisioned at the present, the DSPA will select the path with the shortest overall length. After the successful provisioning of links, it is able to calculate the total bandwidth utilized by the VSR (\(TBW_{SV}\)) and shorest path length \(L_{SV}\).

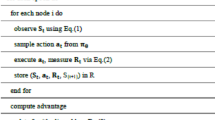

Resource provisioning strategy

Assigning a node and establishing a link between the nodes of the VSRs received between 0 and \(T_{max}\) is the essence of this process comprises. In the proposed work, each VSR is modelled as a set of eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC use cases in order to build a realistic dynamic environment. As a result, slicing the VSR and the PI prior to allocating resources is an absolute requirement. The proposed orchestration architecture comprises a slice creation step that feeds information into the resource allocation phase. This means that during the resource allocation phase, it is guaranteed that all necessary VSR nodes are grouped into eMBB, mMTC, or uRLLC nodes. The proposed resource distribution has been modeled by mapping the VSR slices to the relevant sliced PI. A VSR should be able to obtain all kinds of slice in any quantity without exceeding the maximum number of nodes per request. The whole process involved in the resource allocation phase is presented below in the form of Algorithm 2.

Slice management of D-SIMS

This slice management phase is the final phase of the proposed orchestration framework, which has been initiated according to the input received from the slice isolation phase. D-SIMS offers two strategies, namely self-sustained resource reservation (SSRR) and master slice resource reservation (MSRR). The VNF manager determines the best way to handle unsuccessful use cases in the self-organized slices, which are regarded as the immediate reserves available for service provisioning, in accordance with the SSRR strategy.

When using the master slice as the immediate reserve for service provisioning, the VNF manager accommodates unsuccessful use cases in accordance with the MSRR strategy. Both the slice management strategies find the best possible way to accommodate resources for the unsuccessful VSR from the available resources. The strategy between the two is selected by the VNF manager according to the virtualization of the PI. The VNF manager handles four responsibilities (4R) to manage the resource allocation, such as inner-resource sharing (IRS), priority resource allocation (PRA), dynamic resource recovery (DRR), and request report generation (RRG). Figure 3 describes all four responsibilities of a VNF manager working under two different strategies.

Inner-resource sharing

In this case, the unsuccessful VSR nodes are provided for resource allocation in the ‘alien-slice’. The term ‘alien-slice’ is defined as the slice which accommodates its resources for the use case of different kinds referred as ‘alien-nodes’. An Alien-slice provides a possible kind of ‘quarantine’ for the alien-nodes for a short span of time. Alien-nodes can complete their ‘quarantine’ whenever their associated slice has sufficient resources. The way that alien-slice is taken into account depends on the PI virtualization and strategy that have been chosen. Attempts to prioritize the allocation of resources for unsuccessful use cases necessitate defining the VNF in terms of individual slices. VNF takes on the responsibility of effectively managing resource contention while attempting to allocate resources for critical services and unsuccessful use cases as defined. According to the SSRR strategy, alien-slices are those that can accommodate foreign nodes. In contrast, for MSRR, a master-slice is viewed as a universal alien-slice that can serve any of the three possible use cases by treating them as alien-nodes. As shown in Fig. 3a, when slice ‘uRLLC’ lacks resources, use case ‘\(u^{3}\)’ transforms into an alien node ‘\(A_{u}^3\)’ and obtains the reserved resource from an alien slice under SSRR, while under MSRR, use case ‘\(u^{3}\)’ obtains the reserved resource from the master slice, which itself functions as an alien slice. The allocation of resources for the alien-nodes in the alien-slices is done by using the following equation:

where, \(F_{e}, F_{m}\), and \(F_{u}\) refer to the failed eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC nodes, respectively. \(R_{e,V}, R_{m,V}, and R_{u,V}\) represent the requested resource of eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC virtual nodes. \(R_{e,P}, R_{m,P}, and R_{u,P}\) show the available resources of eMBB, mMTC and uRLLC nodes in PI. \(R_{e,ms}\) denotes available resources of master slice in PI.

Dynamic resource recovery

In this particular scenario, the VNF manager keeps a close eye on the duration of life for each of the individual use cases that have been provisioned at the PI in the past. When it is determined that the use cases do not require the use of PI resources, those resources that were occupied by the use cases are released back into availability. It has been realized that the recovery would benefit from more dynamics if life-time was granted to individual use cases rather than VSRs. Also, in practice, the intended life-span of each individual use case will be different. According to Fig. 3b, for both strategies, the occupied resources of the use cases ‘\(e^{1}\)’, ‘\(m^{1}\)’, and ‘\(u^{1}\)’ are released when it is realized that they have reached the end of their life-time and no longer require service. For the VSR with a life-time LT, the dynamic recovery of the resources is performed by the following equations:

During the time interval \({ 0<t<LT }\),

when \({ t>LT }\),

where, \(R_{P}^{i}\) represents the resources of PI nodes and \(R_{V}^{i}\) represents the required resources of virtual request.

Priority resource allocation

This case manages two kinds of priority provisioning that are alien-centric priority service (ACPS) and latency-centric priority service (LCPS). The ACPS holds that because the quarantine period for the alien-nodes in the alien-slices cannot be extended, serving the alien-nodes must come before serving the new VSR. LCPS, on the other hand, thinks that when it comes to provisioning for nodes, uRLLC services should be given top priority over all other use cases. When the SSRR strategy determines that the resources used by the use cases \(e^{1}\), \(m^{1}\), and \(u^{1}\) have expired, the corresponding alien-nodes \(A_{u}^3\) in the alien slice are relocated to the appropriate slice (see Fig. 3c). To a similar extent, the MSRR method brings back the master slice’s foreign nodes as needed during the course of the use cases’ lifetime. The equation that corresponds to the addressing of two different kinds of priority service provisioning is as follows,

where, Restoration indicates that the value of any alien-nodes are restored if possible when \(LT>t\) for any of the previous requests. \(LT\) indicates life-time of the previous request node and \(t\) denotes dynamic value of life-time. \(A_{e}^{i} \), \(A_{m}^{i} \) and \(A_{u}^{i}\) represents the alien-nodes of eMBB, mMTC and uRLLC nodes.

Request report generation

As this is the case, the VNF manager needs to send the final report of the VSR, regardless of whether it is successful or not. The VNF manager should, at the very least, attempt to assign resources in order to avoid unsuccessful situations. The unsuccessful VSRs will only be realized by the strategies if the PI does not have sufficient resources. According to Fig. 3d, the report is unsuccessful for both strategies because it is discovered that the newly arrived use cases ‘\(e^{4}\)’, ‘\(m^{4}\)’, and ‘\(u^{4}\)’ cannot be provisioned in the physical resources due to resource inadequacy. The following equations are used to compile the information for the report.

where, the value ‘1’ indicates that resource allocated for virtual request node successfully and 0 represents resource allocation is failed.

Simulation results

The suggested dual slice isolation and management strategies, called SSRR and MSRR, are tested separately under a variety of set parameter conditions to get a full understanding of how well they work. Both of these strategies handle all three phases of the execution process, which are as follows: (1) slice creation by deep neural network (SC-DNN), (2) slice isolation by hybrid fuzzy-PROMETHEE (SI-FP), and (3) slice management by four responsibilities (SM-4R). Through the use of the parameters associated with each approach, the efficacy of the approaches used in various phases is evaluated. Table 3 includes a list of the variables taken into account for the test case, including the variety of physical network resources and the VSR for the test scenario. The datasets are classified into three or four categories based on their methods (SSRR and MSRR) : eMBB, mMTC, uRLLC and master slice. The two dataset with 1000 samples are separately generated (SSRR one dataset with three class and MSRR with four class). Based on the parameters provided in the reference study5, we consider the range for attributes in the dataset. Training and testing are conducted using deep neural network with ration of 90:10, 80:20, 70:30. The graphs for the PI and VSR are made using the scale-free network model suggested in48. The proposed work makes use of Python to construct the simulation platform.

D-SIMS through SSRR

According to this strategy, it is assumed that the provided physical infrastructure is virtualized into three slices. In accordance with the characteristics of the use case, the SC-DNN is used to generate three slices for both the PI and the VSR. To account for the dissimilar nature of VSR and PI, we have constructed these performance datasets independently. The CPU capacity, link capacity, bandwidth, jitter, and delay rate are the key parameters identified for use in building the performance dataset26,49. The datasets are categorized as eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC depending on the specific fields they represent. An effort is underway to compile a dataset containing information on 1000 population. DNNs are trained and evaluated using a variety of weight optimization techniques, including ADAM, SGD, and LBFGS. The training-testing ratio is 9:1. DNN use the hyper parameter values for our model such as learning rate 0.001, Batch size 32, Number of layers 4, Activation function ReLU. To evaluate the relative effectiveness of various optimization techniques, we use metrics like precision, recall, and F1 score. DNN methods are implemented using the scikit-learn python library. The precision, recall, and F1 score outcomes for PI using DNN with various weight optimizations are displayed in Fig. 4a–c. As shown in the figure, there are three major categories of approaches being evaluated, where each achieves performance levels of almost 90% in terms of precision, recall, and F1-score. As measured by the overall percentage of correct predictions in the performance dataset, ADAM is superior to competing methods. Figure 5 displays the results of these three supervised DNN methods at different training-to-testing ratios, providing yet another illustration of their usefulness. Overall, the figure demonstrates that the ADAM method achieves a higher rate of accuracy than competing methods.

In the SI-FP phase, hybrid fuzzy-PROMETHEE is used to map VSR nodes in PI and their corresponding links. At this stage, as shown in Fig. 6, priority is given to allocating resources for isolating slices. This scheme is evaluated by assuming that PI is equipped with 100, 200, and 300 nodes, with request nodes ranging from 100 to 800. The values for the network features are drawn at random from the range shown in Table 3. Each link in the graph has a fixed length of 1 unit so that performance can be more accurately measured. Node-generated values from the preceding phase are made available as slices in PI and VSR for use in resource allocation. The SI-FP system ensures that the needed VSRs have access to the necessary nodes and links by assigning the resources of PI slices to VSR slices in an optimal manner. If the SI-FP scheme fails to allocate the necessary resources for VSR, the SM-4R phase begins to support the resource allocation process. SM-4R is in charge of four tasks that assess the viability of VSR resource allocation and, ultimately, the VSR’s success or failure. Both resource efficiency and acceptance ratio are enhanced by the synergistic use of SI-FP and SM-4R.

In Fig. 6a, we can see the aggregated findings concerning VSRs and resource efficiency, which show that resource efficiency decreases with an increase in the number of nodes by the VSR, while efficiency rises as more nodes are added to the physical infrastructure. Shorter paths between nodes in a larger network means more efficient use of resources, as predicted by the resource efficiency equation. When a 100-node PI is used to allocate resources to 800 virtual request nodes, resource efficiency is recorded as 0.7. Resource efficiency improves as well with increasing in node counts, reaching an optimal value of 0.8 when 100 virtual nodes are requested at the PI equipped with 300 nodes.

In terms of the acceptance ratio, it can be seen in Fig. 6b that it rises whenever the number of nodes in the PI network expands. This is the case even though more nodes are present. There are more nodes now, therefore a larger percentage of the population is on get on with it. With a shorter use case’s lifespan comes a higher acceptance rate. When servicing 800 use cases in PI with 300 available nodes, the proposed technique obtains an acceptance ratio of 0.9. In addition, as can be seen in Fig. 7a, it may accommodate ranging from a minimum of 1494 CPUs up to a maximum of 12,540 CPUs within an infrastructure of 100 to 300 nodes. As can be seen in Fig. 7b, the bandwidth requirements for the same operational state range from a high of 37,158 to a low of 4250.

D-SIMS through MSRR

This strategy makes the assumption that the physical infrastructure is virtualized into four slices, including the master slice, eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC. In contrast, the VSR is divided into three slices based on the traits of use cases. Slices are produced for both the PI and the VSR using SC-DNN. Similar to the previous approach, we have independently built these performance datasets using key parameters due to the differences between VSR and physical infrastructure. The nodes with the highest KPI values are kept inside the master slice for PI because they must act as an alien slice for all three types of use cases. eMBB, mMTC, and uRLLC are the three remaining PI nodes, which are divided among them based on the particular fields they stand for. Similar to the previous approach, a work is being done to create a dataset with data on 1000 population. The three DNN techniques are used to measure the performance of slice classification. The results of slice creation measures such as precision, recall, and F1 score for PI using various DNN techniques with a 9:1 training to testing ratio are shown in Fig. 8a–c.

The accuracy measure for various training and testing ratios is shown in Fig. 9. It is clear from both Figs. 8 and 9 that the ADAM method outperforms the other two methods in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. After the slices in PI and VSR have been created, the SI-FP phase can then continue. The creation of the PI slices takes place at the very beginning, before the first VSR is received, and these slices do not undergo any changes until the end of the total time frame.

The slice for the VSR is generated as soon as the new VSR arrives and submits a request to the PI for resource allocation. The effectiveness of MSRR is evaluated using PI equipped with 100, 200, and 300 nodes, much like the prior strategy. The values for the network features are chosen at random from the range shown in Table 3, and the VSRs are received with a random number of node requests. The SM-4R phase works with the SI-FP to find the best way to turn the unsuccessful VSR into a successful one in order to increase resource efficiency and acceptance rate. When determining the best way to allocate resources, all three performance criteria are taken into account. The results are displayed in Figs. 10 and 11, and they are broken down into categories such as resource efficiency, acceptance ratio, and CPU and BW consumption, respectively. Resource efficiency of 0.8, 0.7, and 0.6 under the PI equipped with 100, 200, and 300 nodes for the total request of 800 nodes are clearly seen in Fig. 10a. When the PI is equipped with 100 and 300 nodes and the total number of requested nodes is 100 and 800, respectively, the acceptance ratio is recorded as having a minimum of 0.7 and a maximum of 0.9, as shown in Fig. 10b. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 11a, it may accommodate between 100 and 300 nodes, each with a minimum of 1481 CPUs and a maximum of 12112 CPUs. Bandwidth utilization varies between a maximum of 29,662 and a minimum of 4006 in Fig. 11b for the same operational state.

Discussions

Through a series of comparisons with the aforementioned literature, this section demonstrates the efficacy of the MSRR and SSRR of D-SIM strategies, in particular with respect to VNE-NTANRC29, SVM-VNE35 and SCE-DIVS38. We assumed that all of the proposed algorithms would have access to the dynamic provisioning service for network requests. Evaluating how well and widely those requests are accepted when the PI has 300 nodes and is responsible for managing a wide variety of network requests is important. Figure 12 shows the algorithms’ relative performance in a number of different settings. It is clear from Fig. 12a that when all other methods are combined, the VNE-NTANRC approach has the lowest throughput. The SVM-VNE and SCE-DIVS algorithms outperformed the VNE-NTANRC algorithm. In addition, both D-SIM techniques exhibit superior performance in comparison to other evaluated algorithms. In terms of optimal resource allocation, the SSRR method is marginally superior to the MSRR technique. The least resource efficiency obtained by the two methods in the PI outfitted with 300 nodes and 800 VSR is 0.73 for MSRR and 0.74 for SSRR, with SSRR producing a 10% increase in resource efficiency over VNE-NTANRC. The adoption rate of the offered strategies is compared in similar conditions. Figure 12b illustrates the outcomes of the algorithms’ successful execution in the context of a 300-node physical infrastructure. The acceptance rate decreases as the total number of node requests rises.

Conversely, when VSR life-spans are lowered, acceptance ratios tend to increase as well. When adopting the SSRR technique, it is possible to achieve a maximum acceptance ratio of 1 and a minimum acceptance ratio of 0.62 when serving a total of 100 and 800 requested nodes. Other algorithms, such as MSRR, generate a lower acceptance rate than SSRR. The VNE-NTANRC, which serves 800 request nodes, has the lowest overall acceptance rate of 0.5. The effectiveness of the provided methods is validated by contrasting the time required to perform the task with other metrics, such as resource efficiency and acceptance rate.

Execution duration’s for provisioning requests of different node counts are compared in Fig. 13. In general, the time needed to execute the algorithmic procedures scales linearly with the sum of the request nodes and the number of accessible nodes in the physical infrastructure. The SSRR algorithm for allocating resources takes significantly longer than the MSRR technique to finish in all operational situations. The MSRR takes less than ten milliseconds to service nodes with values between 100 and 300 when the underlying physical infrastructure has 100 nodes. In addition, the PI with 300 nodes needs a response time somewhat longer than 10 ms, despite servicing the same number of customers. Nonetheless, under PI with 300 nodes, the allocation procedure can be finished by either strategy in less than 100 ms.

Conclusion

The proposed work provides D-SIMS called SSRR and MSRR for effective network slicing. The way the physical infrastructure is sliced has been modeled as influencing the choice strategies. In addition, the orchestration frameworks of both techniques are ready to solve the three network slicing components, namely slice creation, isolation, and management. With the aid of a performance dataset that included the crucial KPIs of the nodes, deep neural networks were used to create slices for PI and VSRs. Isolating slices has been accomplished using both the Hybrid Fuzzy PROMETHEE for node mapping and Dijkstra’s approach for link mapping. In order to improve resource usage, slice management was combined with the slice isolation phase. Four VNF functions were constructed to handle the VNF manager’s four responsibilities. The performance of the suggested techniques has been investigated under various PI and VSR conditions. The findings obtained were compared to those found in the previous research to ascertain the efficacy of the proposed method. It has been determined that both the SSRR and MSRR strategies of D-SIM outperformed previous work. More specifically, the framework based on the SSRR method provides better performance than MSRR. In the worst-case scenario, when provisioning 800 request nodes in a PI of 100 nodes, SSRR achieved a maximum resource efficiency of 0.7 and an acceptance ratio of 0.6. As a result, it is therefore suggested that under the three slice virtualization of PI, proper management strategies will lead to increased performance. The current work can be expanded in the future to cover the mobility and energy management of several use cases.

Data availability

The datsets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Henry, S., Alsohaily, A. & Sousa, E. S. 5G is real: Evaluating the compliance of the 3G pp 5G new radio system with the ITU IMT-2020 requirements. IEEE Access 8, 42828–42840 (2020).

Foukas, X., Patounas, G., Elmokashfi, A. & Marina, M. K. Network slicing in 5g: Survey and challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 55, 94–100 (2017).

Afolabi, I., Taleb, T., Samdanis, K., Ksentini, A. & Flinck, H. Network slicing and softwarization: A survey on principles, enabling technologies, and solutions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 20, 2429–2453 (2018).

Chang, C.-Y. & Nikaein, N. Ran runtime slicing system for flexible and dynamic service execution environment. IEEE Access 6, 34018–34042 (2018).

Guan, W., Wen, X., Wang, L., Lu, Z. & Shen, Y. A service-oriented deployment policy of end-to-end network slicing based on complex network theory. IEEE Access 6, 19691–19701 (2018).

Min, Z. et al. A novel 5g digital twin approach for traffic prediction and elastic network slice management. In 2024 16th International Conference on Communication Systems & NETworkS (COMSNETS) 497–505 (IEEE, 2024).

Ferrus, R., Sallent, O., Pérez-Romero, J. & Agusti, R. On 5g radio access network slicing: Radio interface protocol features and configuration. IEEE Commun. Mag. 56, 184–192 (2018).

Kotulski, Z. et al. Towards constructive approach to end-to-end slice isolation in 5g networks. EURASIP J. Inf. Secur. 2018, 1–23 (2018).

Li, X., Guo, C., Gupta, L. & Jain, R. Efficient and secure 5g core network slice provisioning based on Vikor approach. IEEE Access 7, 150517–150529. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2947454 (2019).

Ogino, N., Kitahara, T., Arakawa, S. & Murata, M. Virtual network embedding with multiple priority classes sharing substrate resources. Comput. Netw. 112, 52–66 (2017).

Liao, J., Feng, M., Qing, S., Li, T. & Wang, J. Live: Learning and inference for virtual network embedding. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 24, 227–256 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. A unified enhanced particle swarm optimization-based virtual network embedding algorithm. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 26, 1054–1073 (2013).

Shahin, A. A. Memetic multi-objective particle swarm optimization-based energy-aware virtual network embedding (2015). arXiv preprint arXiv:1504.06855

Melo, M., Sargento, S., Killat, U., Timm-Giel, A. & Carapinha, J. Optimal virtual network embedding: Node-link formulation. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 10, 356–368 (2013).

Pathak, I. & Vidyarthi, D. P. An optimal virtual network mapping model based on dynamic threshold. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 83, 2381–2401 (2015).

Xu, Q., Wang, J. & Wu, K. Learning-based dynamic resource provisioning for network slicing with ensured end-to-end performance bound. IEEE Trans. Network Sci. Eng. 7, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSE.2018.2876918 (2020).

Butt, M. M., Pantelidou, A. & Kovács, I. Z. Ml-assisted UE positioning: Performance analysis and 5g architecture enhancements. CoRR (2021). arXiv:2108.11365

Alazab, M. et al. Deep learning for cyber security applications: A comprehensive survey (2021).

Wu, Z.-X., You, Y.-Z., Liu, C.-C. & Chou, L.-D. Machine learning based 5g network slicing management and classification. In 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC) 371–375 (IEEE, 2024).

Bega, D., Gramaglia, M., Banchs, A., Sciancalepore, V. & Costa-Pérez, X. A machine learning approach to 5g infrastructure market optimization. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 19, 498–512 (2019).

Archanaa, R., Athulya, V., Rajasundari, T. & Kiran, M. V. K. A comparative performance analysis on network traffic classification using supervised learning algorithms. In 2017 4th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS) 1–5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACCS.2017.8014634

Patro, S., Rath, H. K. & Panigrahi, B. Dynamic KPI-aware network slicing for 5g+ networks. In 2024 IEEE 13th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT) 94–99 (IEEE, 2024).

Gupta, R. K. & Misra, R. Machine learning-based slice allocation algorithms in 5g networks. In 2019 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Control (ICAC3) 1–4 (IEEE, 2019).

Immadisetti, M. K. N., Murukessan, A. & Srinivas, M. Automate allocation of secure slice in future mobile networks using machine learning. In 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT) 1–7 (IEEE, 2021).

Thantharate, A., Paropkari, R., Walunj, V., Beard, C. & Kankariya, P. Secure5g: A deep learning framework towards a secure network slicing in 5g and beyond. In 2020 10th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC) 0852–0857 (IEEE, 2020).

Abidi, M. H. et al. Optimal 5g network slicing using machine learning and deep learning concepts. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 76, 103518 (2021).

Jiang, H., Wang, Y., Gong, L. & Zhu, Z. Availability-aware survivable virtual network embedding in optical datacenter networks. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 7, 1160–1171 (2015).

Javadpour, A., Ja’fari, F., Taleb, T. & Benzaïd, C. Enhancing 5g network slicing: Slice isolation via actor-critic reinforcement learning with optimal graph features. In GLOBECOM 2023—2023 IEEE Global Communications Conference 31–37 (IEEE, 2023).

Cao, H., Yang, L. & Zhu, H. Novel node-ranking approach and multiple topology attributes-based embedding algorithm for single-domain virtual network embedding. IEEE Internet Things J. 5, 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2017.2773489 (2018).

Zhang, P., Yao, H. & Liu, Y. Virtual network embedding based on computing, network, and storage resource constraints. IEEE Internet Things J. 5, 3298–3304. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2017.2726120 (2018).

Wang, Y. & Ye, C. Individualized resource allocation for 5g network slicing based on knapsack stragegy. In 2023 International Conference on Computer Science and Automation Technology (CSAT) 383–387 (IEEE, 2023).

Liu, J., Zhao, B., Shao, M., Yang, Q. & Simon, G. Provisioning optimization for determining and embedding 5g end-to-end information centric network slice. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 18, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2020.3045051 (2021).

Tariq, M. A. et al. Network slice traffic demand prediction for slice mobility management. In 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC) 281–285 (IEEE, 2024).

Venkatapathy, S., Srinivasan, T., Jo, H.-G. & Ra, I.-H. Optimal resource allocation for 5g network slice requests based on combined promethee-II and SLE strategy. Sensors 23, 1556 (2023).

Mei, C., Liu, J., Li, J., Zhang, L. & Shao, M. 5g network slices embedding with sharable virtual network functions. J. Commun. Netw. 22, 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1109/JCN.2020.000026 (2020).

Pentelas, A., Papathanail, G., Fotoglou, I. & Papadimitriou, P. Network service embedding across multiple resource dimensions. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 18, 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2020.3044614 (2021).

Wang, Y. & Hu, Q. A path growing approach to optical virtual network embedding in slice networks. J. Lightw. Technol. 39, 2253–2262. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2020.3047713 (2021).

Thanh, N. H. et al. Energy-aware service function chain embedding in edge–cloud environments for IOT applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 8, 13465–13486. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2021.3064986 (2021).

Fan, W., Xiao, F., Chen, X., Cui, L. & Yu, S. Efficient virtual network embedding of cloud-based data center networks into optical networks. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 32, 2793–2808. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2021.3075296 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Cao, H., Su, S. & Li, W. Energy aware virtual network migration. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 10, 1173–1189. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCC.2020.2976966 (2022).

Luu, Q.-T., Kerboeuf, S. & Kieffer, M. Admission control and resource reservation for prioritized slice requests with guaranteed SLA under uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag.https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2022.3160352 (2022).

Gao, L., Li, P., Pan, Z., Liu, N. & You, X. Virtualization framework and VCG based resource block allocation scheme for LTE virtualization. In 2016 IEEE 83rd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring) 1–6 (IEEE, 2016).

Balachandran, A. & Amritha, P. P. VPN network traffic classification using entropy estimation and time-related features. In IOT with Smart Systems (eds Senjyu, T. et al.) 509–520 (Springer, 2022).

Prasad, J., Senthil, M., Yadav, A., Gupta, P. & K S. A. A Comparative Study of Machine Learning Algorithms for Gas Leak Detection 81–90 (2020).

Kylili, A., Christoforou, E., Fokaides, P. A. & Polycarpou, P. Multicriteria analysis for the selection of the most appropriate energy crops: The case of cyprus. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 35, 47–58 (2016).

Gul, M., Celik, E., Gumus, A. T. & Guneri, A. F. A fuzzy logic based Promethee method for material selection problems. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 7, 68–79 (2018).

Makariye, N. Towards shortest path computation using Dijkstra algorithm. In 2017 International Conference on IoT and Application (ICIOT) 1–3 (IEEE, 2017).

Barabási, A.-L. & Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286, 509–512 (1999).

Pakzad, F., Portmann, M. & Hayward, J. Link capacity estimation in wireless software defined networks. In 2015 International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC) 208–213 (IEEE, 2015).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by "Regional Innovation Strategy (RIS)" through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) (2023RIS-008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing (original draft) and methodology: S.V. and T.S.; writing (review and editing): H.-G.J. and I.-H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Venkatapathy, S., Srinivasan, T., Lee, OS. et al. Slice-aware 5G network orchestration framework based on dual-slice isolation and management strategy (D-SIMS). Sci Rep 14, 18623 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68892-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68892-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comprehensive analysis on 5G and 6G wireless network security and privacy

Telecommunication Systems (2025)