Abstract

Cancer affects patients as well as their spouses. Patients and their spouses use different strategies to cope with cancer and the associated burden. This study aimed to gain a deeper and more differentiated understanding of support systems for patients and their spouses. This was an exploratory qualitative study conducted in China. The study was based on 20 semistructured face-to-face interviews. Ten pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses were interviewed. The interviews took place at a tertiary hospital from June 2023 to December 2023. The data were analysed using thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke's methodology. This study was guided by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist. Twenty participants of different ages (patients: range = 49–75 years; spouses: range = 47–73 years) participated. Patients with different cancer stages (e.g., potentially resectable, borderline resectable, locally advanced) and cancer types (initial diagnosis or relapse) participated in the study. Five themes emerged from the data, namely, denial and silence, fear and worry, struggle, coping strategies and cherishing the present. Active dyadic coping is conducive to promoting disease adaptation, and spouses seem to need more psychological support to improve their own well-being. Health care providers should pay attention to pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses in terms of five themes: denial and silence, fear and worry, struggle, coping strategies and cherishing the present. Future studies should use a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to explore dyadic coping in greater depth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a malignant disease with high morbidity and a high mortality rate1. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for approximately 90% of all cases of pancreatic cancer. Patients often have no obvious symptoms or signs in the early stage of disease, and more than half of patients are in the late stage at the time of diagnosis. According to the latest data of the American Cancer Society published in 2022, the incidence rate of pancreatic cancer ranks 10th among men and 7th among women among all cancer types; however, pancreatic cancer ranks 4th in cancer mortality, and the 5-year survival rate of pancreatic cancer is the lowest among all tumours, at only 11%2. Due to the great uncertainty about treatment effectiveness and the risk of cancer, pancreatic cancer causes a great psychological burden for patients’ spouses3. These couples face new challenges (e.g., being unable to effectively obtain information about the disease and its treatment, having high medical bills), role function transformation (e.g., having to stop working, managing family affairs) and self-concept changes (e.g., negative emotions, nervous about the future)4.

A cancer diagnosis has a profound impact on patients and their spouses, affecting multiple dimensions, such as the emotional, psychological, social, and economic dimensions. A cancer diagnosis often elicits a strong emotional response, encompassing shock, denial, anger, sadness, and fear5. Patients, as well as their spouses, may experience symptoms of anxiety and depression, which are normal reactions to the news of a cancer diagnosis. In some cases, professional mental health services may be necessary to help individuals manage these emotions6. A cancer diagnosis affects not only patients but also their family members and social networks. Patients’ spouses may need to take on more caregiving responsibilities while also dealing with their own emotional reactions. This additional stress can affect their work performance and social activities and may even lead to increased tension within the family7. Cancer itself, as well as its treatment, can have long-term, even permanent, effects on a patient's body. These effects include pain, fatigue, weight changes, skin changes, decreased libido, and fertility issues. Spouses may also neglect their own health while caring for patients. Patients and their spouses must communicate and cooperate when facing complex medical choices due to the diagnosis of cancer8. Effective communication can help both parties better understand their condition, treatment options, and potential risks and benefits, thereby helping them make informed decisions.

Some cancer patients also need support to cope with cooccurring mental health issues9. The multiple impacts of cancer on patients and their spouses have prompted researchers to conceptualize cancer as a dyadic stressor10. Taking spouses as the unit of analysis and considering the interactions that occur in the interdependent system between spouses can provide us with a new perspective on understanding the psychological distress and coping strategies of couples after cancer diagnosis11,12. How patients and their spouses deal with cancer affects the mental health of both parties and their assessments of relationship satisfaction13.

Research on coping styles for individuals with cancer has shifted from the individual level to the couple level14. Bodenmann noted that for couples, stress events do not affect the individual reactions of only one party but have common effects on both parties15. Coping with cancer and its related burdens requires collaboration, which is called dyadic coping (DC), which refers to the common reactions and strategies of spouses with intimate relationships when facing dual stress events15. The couple relationship is one of the most important resources for patients to cope with stressful events. Traditional models such as the systemic transactional model emphasize that both spouses should jointly perceive and evaluate stress, help each other, promote each other’s physical and mental health, and strengthen their intimate relationship16,17,18 when coping with stress. Spouses play a key role in treatment decisions and in facilitating disease management19. According to dyadic disease management theory20, coping behaviour is a factor related to quality of life. The dyadic perspective of couples, focusing on the dyadic response of cancer patients and their spouses, is a new perspective for improving the physical and mental health of both parties and improving quality of life21,22. Couples facing cancer usually adopt a dyadic response23 to reduce disease pressure.

Quantitative research on coping with cancer is very extensive, but there have been few qualitative studies in this field. A recent qualitative study of pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses reported coping strategies such as changing roles and identities, managing weight loss and addressing gastrointestinal problems24. A systematic review identified coping strategies such as symptom management, better clinical communication, support seeking, and maintaining a good attitude25. However, less is known about the use of different types of coping strategies by patients and their spouses and social support styles from outside couples.

In summary, we aimed to explore couples in which one spouse had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, including how the couple coped with the disease together and what coping and support strategies they used. In addition, we aimed to identify possible differences in coping behaviour between patients and their spouses. Insight into specific types of coping strategies can improve the development of more tailored and detailed intervention programs for cancer patients and their spouses.

Methods

Study design

A qualitative design was used in this study. Reporting was performed in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) reporting guidelines26.

Participants

Participants (patient-spouse dyads) from a tertiary hospital in China were recruited through random sampling from June 2023 to December 2023. The research team identified potential eligible participants through the hospital's patient registration system. Patients who met the preliminary conditions were invited to participate by the research team. Potential spouse participants were identified and recruited through direct communication with patients. Eligibility was based on the following criteria: having a diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), being aged 18–75 years, being hospitalized for 2 weeks or more, and living with a spouse. The exclusion criteria for patients were severe cognitive impairment; serious heart, lung, kidney or other diseases; and consciousness disorders. The inclusion criterion for spouses was the ability to communicate normally. The exclusion criterion for spouses was cognitive impairment. Both patients and their spouses were required to provide written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Procedure

Individual, audio-recorded, semistructured in-depth interviews23 were conducted by creating a space for participants to openly share their perspectives. An interview guide, collaboratively developed after performing a literature review, aimed to explore the research interests of this study. Two participants were selected for a pilot interview, and the interview guide was revised and finalized accordingly (Table 1). Those meeting the inclusion criteria were provided with an interview explanatory statement outlining the study's aim and procedures. The statement emphasized voluntary participation, with the option to withdraw at any time without providing a reason. Participants were assured of anonymity, with their personal information remaining confidential and unidentified. Before the interviews, each participant signed an informed consent form.

The interviews were conducted by the first author in the VIP conference room of the hospital department. Patients and their spouses were interviewed separately. During the interviews, participants were encouraged to share their experiences and provide additional comments on the topic. There was no prior relationship between the interviewer and the participants, which helped to reduce bias and ensure the objectivity and accuracy of the research results. The interview ended when no new or surprising information was uncovered during further data collection, that is, when data saturation occurred27. The interviews lasted between 20 and 74 min, with an average duration of 30 min.

Data analysis

Sociodemographic information was reported with basic descriptive statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics 24. At the end of each interview, the authors independently transcribed the recordings into text within 24 h, and then imported the text into NVivo 11 software. We used Braun and Clarke's thematic analysis method28,29. The initial coding was independently carried out by two authors (B. Zhang and Q. Xiao), with a third author regularly monitoring and intervening in case of differing opinions. Encoding attempts to identify and describe aspects and their outcomes were considered to constitute contextual or mechanistic features. Then, the fourth author reviewed all coding results. Group discussions aim to compare, critique, and agree on external or internal factors related to patients and their spouses. In the process of inductive coding and deductive classification, if there was any inconsistency, the researcher discussed the differences with QGX and JTG and reached a consensus. Finally, the research group discussed and reviewed all the identified themes and categories.

After the interview, we transcribed the conversation verbatim and created detailed written records about every interview (i.e., interview memorandum). We also provided interview recordings and transcripts to the interviewees and their spouses for review. The transcripts were then reviewed by the research team to ensure their accuracy. Once research team were confident that the transcripts accurately reflected the interviews, we contacted the interviewees and their spouses to request their feedback. We did this to confirm that they agreed with the transcript's content and that we had not misrepresented any of their words or ideas. If the interviewee and his or her spouse agreed with the content of the transcript, we moved forward with our analysis. However, if there were any discrepancies or errors, research team made the necessary corrections based on their feedback. This ensured that the data we analysed were as accurate and reliable as possible.

Rigor

The authors are all postgraduate students, who have received systematic training and mastered qualitative research methods and interview skills. During the interviews, voice recorders and field notes were used to ensure the quality of the recordings, questions were asked as neutrally as possible, and the participants' responses were neutral. At the end of each interview, two authors repeatedly listened to the recordings to check for accuracy, and then they encoded and analysed the transcripts. If there were new items or disagreements in the transcribed interview, this will be further elaborated in the next interview.

Ethics

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (XJTU1AF2019LSK086). Written informed consent was obtained from participants included in the study. All participants were informed that any personal information obtained in this study would remain confidential.

Results

Among the 13 potential couples who expressed willingness for interviews, ten couples were included in the final analysis. Three couples refused to participate in the study for various reasons, including scheduling conflicts (n = 1), a lack of interest (n = 1) and unwillingness to discuss this topic (n = 1). Patients with pancreatic cancer had a median age of 62.5 (49–75) years. More than half of the patients were men (n = 7); the majority of patients had a secondary school education or below (n = 9) and all patients were married (n = 10). Approximately 50% (n = 5) of the patients were classified as having borderline resectable disease at the initial diagnosis. The duration of pancreatic cancer ranged from 0.5 to 5 years. The median age of the spouses was 63 years (47–73). The majority of spouses had a secondary school education or below (n = 9). Three individuals had previously worked in the field of nursing. Further characteristics are displayed in Table 2 and Supplementary Material.

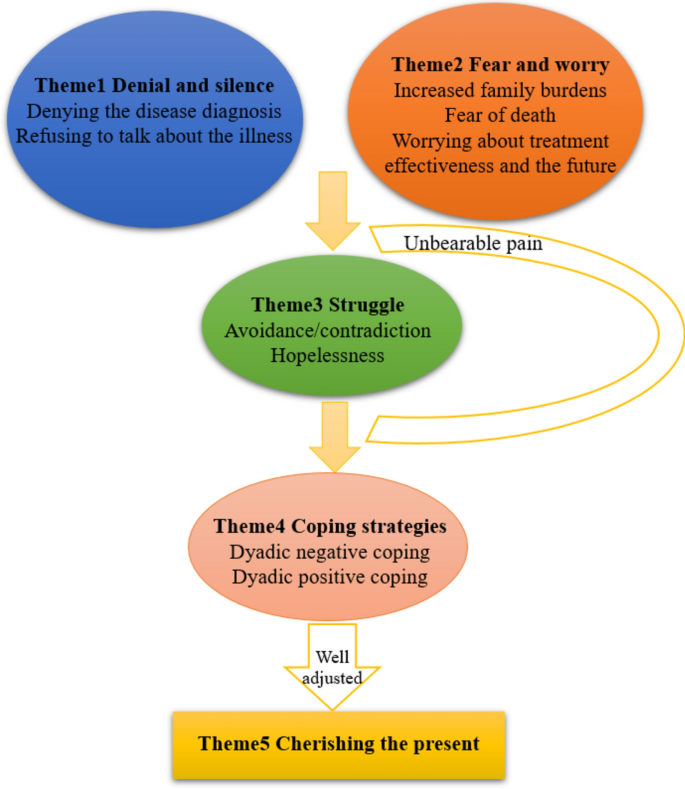

Five themes were extracted from the interviews in this study, which described the experiences and perceptions of patients with pancreatic cancer and their spouses in coping with the disease. The five themes were denial and silence, fear and worry, struggle, coping strategies and cherishing the present. Figure 1 and Table 3 present the themes, subthemes, and representative quotes.

The process of participants' coping to illness. Patients and their spouses fell into denial and silence and filled with fear and anxiety at the beginning. As the disease progressed, they gradually struggled to cope with this situation. During this painful journey, they adopted two different coping strategies: one was a negative coexistence approach within couples, while the other involved actively adjusting their mindset and ultimately learning to cherish the present and harmoniously integrate into life.

Denial and silence

Denial and silence meant that the patients with cancer and/or their spouses did not want to communicate regarding any illness-related issues and that they had not communicated. The essential characteristic was the lack of intention to communicate about the illness, which includes denying the disease diagnosis and refusing to talk about the illness.

Denying the disease diagnosis

Patients and their spouses tended to be sceptical of the diagnosis of the illness and denied it through psychological defence mechanisms. Specifically, some patients admitted that they never expected to have cancer and that the unexpected diagnosis triggered strong feelings of disbelief and resistance. Spouses also mentioned that the patient's diagnosis of cancer was unexpected and refused to accept it.

“When I first got my diagnosis, I felt like the sky was falling, my legs were shaking, my heart was panicking…” (P5)

“It never occurred to me that this would be my husband’s test result. He was only 54, so young, and in good health before.” (S6)

Refusing to talk about the illness

Some patients and their spouses were afraid to communicate about the malignant disease because they feared that it would cause shock or a psychological burden for their spouse and that they could not control their emotions. As spouses, when faced with sudden negative emotions from patients, some respondents were unsure how to comfort them. Some spouses chose to accommodate and remain silent, internalizing the negative emotions. This led to a certain degree of emotional exhaustion.

“I am afraid to tell my wife that her disease is advanced and incurable. I dare not tell her because I am worried that she cannot bear it.” (S4)

“He was in a really bad mood, and I didn’t know how to comfort and console him.” (S1)

Fear and worry

This theme demonstrated participant’s emotion change as they become aware of burden and death as the disease progressed.

Increased family burdens

The diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer had prompted a series of adjustments in family roles to adapt to new responsibilities. Following the diagnosis, the couples bore their respective responsibilities in the dyad and embarked on discussions regarding changes in their roles, considered revising established models for managing household duties, and navigated the interruptions to their life plans. For spouses, the responsibility was to serve the patients wholeheartedly. For patients, the responsibility was to minimize the burden on their spouses as much as possible. Some patients or their spouses also chose to bear pressure alone to alleviate the burden on others. Some families lost their primary sources of income. Additionally, they needed continuous treatment. All these factors increased the financial burden.

“I certainly hope she can help me, but it is already very difficult for her, and I don't want to burden her even more…” (P1)

“My husband is the primary source of income in our family, but now he is unable to work…so the financial pressure is quite significant.” (S3)

“Before she got sick, she used to do more housework at home. Now that she is ill, I must take care of her and do a lot of things every day. ” (S9)

Worrying about treatment effectiveness and the future

The participants were conflicted between having hope for the effectiveness of treatment and being fearful about the progression of the patient’s disease. In addition, they were conflicted about cancer as a disease and their life as a caregiver. Some spouses themselves had diseases. Therefore, they felt anxious about their health problems worsening and taking care of the patient with their health condition. Spouses reported that taking care of their own physical and emotional needs ensured they could continue to participate in caring for the patient. When they realized their limited emotional resources and time, they consciously chose to reduce their efforts towards others. Spouses reported a range of self-care activities, including exercise, dietary modification, and making time for hobbies.

“I always felt down, and… I also felt that I wanted to have hope.” (P3)

“I have to take care of myself before I can start taking care of him.” (S1)

Fear of death

From the moment of diagnosis, the spouse perceived the threat of the patient's death as a real possibility. As they witnessed the changes in their partner's body caused by the disease, this possibility became increasingly concrete. Which prompted them to accept or prepare themselves for their new reality, to anticipate and imagine life without their partner. They accomplished this by seeking out information about the cancer, about the dying process and death. Spouses strived to comprehend the patient's experiences. They hoped that treatment could continue until they no longer felt overwhelmed when considering the remainder of their lives. In other words, their perspectives on life and death deepened when faced with the opportunity to contemplate living until death.

“I was prepared for his death when I discovered his cancer had metastasized. When the doctor told me he had terminal cancer, I knew he would die soon.” (S8)

“We were all gradually coming to terms with the arrival of death, though it was a harsh reality (sobbing).” (P8)

Struggle

At this stage, some patients and their spouses still avoided disease-related topics, and even felt hopelessness.

Avoidance/contradiction

This study showed that many couples tended to cope with stressors by avoiding problems. Some couples had poor adaptation to the diagnosis of the disease, experienced avoidance or contradiction, and perceived minimal dyadic support and greater adaptation difficulties. They rarely or never communicated their feelings about the disease, avoided or retreated from their spouse, and reacted negatively to the pain associated with the disease in others. This included reluctantly providing support, maintaining distance, and even ridiculing each other. Some couples reported that after the onset of illness, both the patient and their spouse prioritized each other's thoughts and feelings over their own in order to maintain normal marital life and avoided increasing the psychological burden on their partner.

“I sometimes look up some information and want to share it with him, but whenever I discuss his condition with him, he pretends to sleep and doesn't want to talk to me (sobbing).” (S6)

“She was exhausted from taking care of me, so I silently endured the bad emotions. I don't want her to worry about me. ” (P5)

Hopelessness

Although patients and spouses were well aware of what to do, sometimes they failed to do the right thing and communicate well, resulting in poor adjustment to the disease. The physical condition of some patients was difficult to improve, and in this case, efforts may be futile. In their view, pancreatic cancer is impossible to cure and the disease is equivalent to a death sentence. Therefore, they believed that any effort was useless, which led to hopelessness. However, hope had proven to be a resource for spouses, helping them cultivate meaning and face adversity. Hope flowed with the progression of the disease and feedback from professionals on treatment outcomes, sometimes being strengthened, sometimes being tempered, but always present until the end of the patient's life.

“Treatment is useless. It's not going to get better; I’m just going to die. ” (P8)

“I often search for information on others overcoming cancer, which brings us a little more hope in our hearts.” (S5)

Coping strategies

Patients and their spouses adopted two different coping strategies after they experienced heavy burdens and painful struggles: dyadic negative coping or positive coping.

Dyadic negative coping

Upon receiving a cancer diagnosis, patients faced a myriad of challenges including physical, cognitive, and psychological barriers, which were frequently accompanied by fluctuating emotions. The illness advanced swiftly, while the responses and engagement of both institution and the assisting professionals lagged behind, being neither timely nor adequate. This discrepancy resulted in profound hopelessness and a sense of incapacity. Concurrently, their spouses endured immense psychological pressure, rooted in anxiety over the patient's condition and the weight of their commitment to caretaking. Some patients and their spouses opted to manage this stress through evasion of difficult topics or by refraining from communication.

At times, partners transmit their emotions to each other, potentially leading to family crises. Patients or their spouses often hid the true condition of the illness and suppressed their own emotions and thoughts to protect their partner, disregarding their own feelings and health. Over time, some couples were more likely to form an evasive way of communicating with others regarding illness-related issues, which often persisted, thus hindering their adaptation to the disease. This deprived couples of opportunities for emotional and stress relief and had a negative impact on relationship quality and marital satisfaction.

“I dare not tell him the truth, worrying it might make him feel even worse.” (S1)

“After my husband got sick, he would often get angry for no reason, and it really weighed on my heart.” (S6)

“I felt like I was drowning, fighting for my life, but I didn't want to leave my husband stranded because of my illness.” (P2)

Dyadic positive coping

Some participants were able to face life setbacks and pain with composure and acceptance. The roles of the spouses were adjusted and adapted. Couples who openly communicated their feelings could better adapt to the disease. Nine patients and spouses expressed that they accepted the existence of the disease: some accepted "fate", and some accepted "disease", choosing to face it calmly. Some spouses were hopeful, believing that with the advancement of medical methods, the situation would improve. Information and instrumental support also play important roles. This included taking care of children, doing household chores, and cooking. In addition, participants obtained from medical staff or the internet and shared disease-related information. The patients experienced care and love and expressed great concern for their spouses. The couples achieved positive results in overall relationship satisfaction and intimacy.

Couples support each other in difficult times and live together for a lifetime, which is the concept of marriage. Spouses made their "being there" commitment in words or actions to support their partners with cancer. The couples stated that the disease was a part of their marriage journey and they were committed to supporting each other. Patients received immense emotional support from the verbal commitments of their spouses. Spouses spent more time with patients, which helped to enhance the intimacy between the couples and aided them in coping with the disease more effectively.

Actively seeking external support was also important. The patients reported that understanding and moral support from friendly, patient, and well-trained doctors and nurses was important. The spouses believed that the treatment of a psychological counsellor was equally important. Overall, many people suggested providing psychological support. The spouses expressed a hope for more proactive services in clinical settings.

“Later, I just resigned to fate. Whenever I had a solution, I would try my best to develop in a positive direction. I chose to face and accept reality. I'm already 68 years old now, and it's worth it.” (P3)

“However, I am glad to have a psychological counsellor. A person who understands me. Someone said, "Yes, you're facing difficulties right now, but you can do it, you'll get rid of it.” (P2)

“My wife gave me tremendous confidence and consistently supported me, affirming that regardless of the illness I had and whatever the outcome, she would always be there to support me in the end. ” (P10)

Cherishing the present

Everything has two sides, and terrible experiences can stimulate positive thinking. After experiencing this significant upheaval, the majority of the participants expressed varying degrees of cherishing the present moment and maintaining a positive outlook towards the future. Some couples came to accept and adapt to the consequences of the disease after receiving chemotherapy. They engaged in discussions about what the experience of cancer signified for themselves individually and for their relationship as a whole. This involved jointly envisioning the future, creating plans, and striving to bring their lives back onto a stable path.

This theme was observed among all participants, who expressed a desire to cherish the present moment and whose marital relationships were strengthened by the caregiving experience. Moreover, to experience prosperity for the rest of their lives, they also needed other significant others to help them live. Therefore, they needed connections with society, including family members. The patients and their spouses appreciated each other more and perceived warmth from family and friends. In the interviews, they all mentioned that the love and support of people around them were important sources of strength for them to deal with the cancer diagnosis. One patient reported that he was particularly grateful for his boss’s support. During his treatment, they also helped him pay for his pension insurance and provided a minimum living allowance of 2000 RMB per month.

“The genuine concern from family and friends that can be felt at all times, everyone is concerned about me…” (P7)

“I believe we can move forward. My wife and I are doing everything we can to save money for the next stage of treatment.” (S9)

“With the advancement of science and technology, I believe that tomorrow will be better.” (S4)

Discussion

Characteristics of the DC styles of pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses

The findings of this study indicate that within the DC style of PDAC patients and their spouses, both positive coping and negative coping strategies coexist.

Dyadic coping is beneficial for the adaptation and recovery of patients' physiological functions30. Patients and spouses have diverse coping styles, most of which involve positive coping styles. They seek emotional comfort and meaning through their relationships with the present, themselves, and others, achieving personal growth.

Positive binary coping can shape patients’ and spouses’ optimistic attitudes towards the disease, which helps them cope with treatment. Medical staff can carry out interventions, such as life meaning therapy interventions31, by promoting an understanding of the present, reviewing life, and facing the future, and patients and spouses can reunderstand their responsibilities, tap into their potential, and find the meaning of life. Training programs such as communication skills training for couples32, cognitive-behavioural therapy33, and coping enhancement training34 can also be carried out to improve communication skills and alleviate negative emotions between partners. Therefore, future research should emphasize training plans for pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses to improve their DC ability.

The dyadic relationships between partners influence each other34. This study revealed that patients and their spouses have consistent coping strategies for accepting reality and perceiving warmth, while there are differences in coping strategies for harbouring hope. In terms of consistent coping styles, patients’ and spouses’ coping styles resonate with each other and have a positive impact, while tension and pain are mostly related to inconsistent coping styles with coping with or releasing emotions between partners35. For example, when facing cancer, patients both avoid and accept it, while their spouses have high levels of anxiety. The anxiety of one partner influences the other partner, indicating that inconsistency in coping styles has an impact on disease management.

A lack of communication or fear of communication has a negative effect on dyadic coping. Open communication is crucial for couples dealing with cancer36. A previous study developed a communication skills training program for cancer patients and their spouses37, which could improve the avoidance of cancer-related topics and intimate relationships with spouses. This program is an effective intervention to promote communication and expression in couples. Our study reported the relaxing effect of communication about stress, while some spouses could not tolerate patients’ communication about stress. To improve this difference, couple-based supportive interventions should shift general communication to more individual approaches38. Because couples with good relationships may be more willing to participate in interviews, there are generally fewer reports of negative dyadic responses. In fact, the interviews were conducted jointly with both partners, which may have reduced the opportunity to observe negative dyadic responses.

Challenges to DC for PDAC patients and their spouses

This study showed that the five couples tended to cope with stressors by avoiding problems. This coping strategy will lower patients’ self-esteem and increase negative emotions. Therefore, healthcare professionals should adopt a comprehensive approach when treating couples, evaluate their attitudes towards the disease in a timely manner, encourage open communication, and cultivate confidence in overcoming the disease.

Most participants said that in addition to guidance from medical staff, the internet was a main source of information. Therefore, comprehensive explanations on disease progression and treatment processes should be provided to patients and spouses who have limited understanding of the disease. In addition, mobile device-based39 communication and consulting platforms can be established to meet their information needs.

The research results also indicate that spouses have greater anxiety and unease than patients, but this is often overlooked40. During the interview process, the spouses mentioned that they always tolerated the patient's uncontrollable emotions. This shows that in the process of taking care of patients, spouses tend to hide their emotions, focus on the patient, and expect improvement of the disease. This suggests that medical personnel should pay attention to the needs of spouses and take effective measures to intervene in a timely manner, such as by providing music therapy41, mindfulness stress relief therapy42, and cognitive behavioural interventions43. This not only has positive effects on the treatment and rehabilitation of cancer patients but also reduces the burden of care, alleviates psychological distress, and improves the quality of life of spouses.

In this study, more than half of the households had a per capita monthly income below 5000 RMB, and the patients were at risk of not being able to resume their work. Economic conditions can affect family relationships, and lower income is associated with reduced intimacy between spouses44. This means that when there are multiple treatment options for cancer, health care professionals should fully consider the financial situation of the patient's family and encourage couples to actively participate in medical discussions. The purpose is to minimize treatment costs as much as possible. In addition, promoting public welfare measures can help alleviate the financial burden on patients whose families are facing economic difficulties.

Providing additional support for DC between patients and their spouses

This study indicated that the family is the most reliable resource for patients and spouses. Strong family relationships bring multiple benefits to individuals, including faith, hope, and peace45. At the same time, the binary coping styles of patients and spouses towards stress can affect their adjustment to life after illness. Negative binary coping is negatively correlated with the prognosis of patients and their relationship with their spouse46. The greater the quality of the relationship between spouses is, the less depressive symptoms they experience. Therefore, family interventions in clinical practice, such as psychological and spiritual integration therapy, meditation, and meaningful therapy, are recommended to alleviate patients’ psychological pain and enhance family relationships and functions47. Patients with decent abilities can also be encouraged to actively care for their family members, do what they can, and express their love to their family members more often; they can also give positive encouragement regarding their spouse's efforts, making them feel responsible and willing to maintain their strength and resilience.

During the coping process, the couple's cognition of cancer was self-assessed and restructured. Their trust in doctors could illustrate this. They readily adopted almost all of the doctor's advice, which implied that when they entrusted themselves to the doctor, their belief in the therapeutic effect and control over the disease was strengthened. They also cultivated interests (e.g., mindfulness meditation and watching television) to take their minds off the diagnosis of cancer. Couples dealing with cancer focused on moving forward, striving to improve the consequences and expectations of the disease. With their efforts and positive coping strategies, the threatening disease cognitions that hindered psychological adaptation were gradually replaced by constructive disease perceptions.

Spouses' distress could be indirectly alleviated by instrumental social support for patients48. Peer support from other patients (through sharing experiences and communication) and professional psychological counselling can effectively reduce psychological symptoms and improve cognitive abilities49. Therefore, health care professionals should recognize the importance of peer support and psychotherapy and encourage patients and their spouses to attend peer support groups for pancreatic cancer survivors to pay timely attention to their psychological status50. Psychological and social interventions for cancer patients and their spouses should be adjusted according to their needs and desires, as well as the nature and stage of the disease51. For pancreatic cancer, a malignant disease, intervention measures should focus on alleviating depression, demoralization, and distress about dying and death, as well as addressing multiple challenges of disease and treatment. These include making treatment decisions and communicating with healthcare providers; adapting to diseases on self-concept, personal relationships, and sense of meaning in life; and preparing for the end of life. Overall, interventions should be developed to strengthen couples’ social support systems.

Study strengths and limitations

The primary strength of this research is that it addressed an overlooked area in relation to coping experiences in pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses. Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis method was used for analysis. By adhering to the six steps and closely involving all members of the research team, the quality of the analysis process of this research topic was ensured. This study also has several limitations. Firstly, we recruited a relatively small sample of participants. However, considering the relatively narrow focus of the study, the sample size was considered sufficient to achieve our goals. In addition, the team unanimously believed that the data was already saturated. Secondly, this study only collected data from one tertiary hospital. Therefore, the generalizability of our results might be limited. However, according to the discussion of the research team, the data consulted in this study could represent the views of a considerable number of patients and their spouses.

Clinical implications

The couples are supportive for and to each other. The results of this study revealed that spousal caregivers cared for patients while also experiencing health issues themselves. Healthcare professionals should provide support for couples coping with cancer, especially by focusing on spouses' psychological conditions because their distress is easily overlooked. These new insights can serve as a new direction for couples' interventions in the future. Spousal caregivers need education about the treatment and support in coping with pancreatic cancer. Thus, more attention is needed for awareness of the patient’s medical condition, managing the side effects of treatment, and the support system of the patients and their spouses. Furthermore, healthcare professionals can help in identifying and resolving the unmet needs of patients and their spouses.

Conclusion

This study showed a dynamic and complex picture of the coping experience between people with pancreatic cancer and their spouses. Patients and their spouses experienced diverse emotional changes and coping styles, that was, denial and silence, fear and worry, and struggle. They presented different coping strategies, that was, negative or positive coping, and finally chose to accept reality and cherish the present. A better understanding of the different conditions and experiences of coping with cancer could inform the design of a feasible and effective patient and spouse support program for coping with pancreatic cancer. Future studies should use a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to explore dyadic coping in greater depth.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, M., Tang, D., Yang, T., Qian, D. & Xu, R. Apoptosis triggering, an important way for natural products from herbal medicines to treat pancreatic cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 796300. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.796300 (2022).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 7–33 (2022).

Yanai, Y. et al. A feasibility study of a peer discussion group intervention for patients with pancreatobiliary cancer and their caregivers. Palliative Supp. Care 20, 527–534 (2022).

Dengso, K. E. et al. The psychological symptom burden in partners of pancreatic cancer patients: A population-based cohort study. Supp. Care Cancer 29, 6689–6699 (2021).

Stenberg, U., Ruland, C. & Miaskowski, C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-Oncology 19, 1013–1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1670 (2010).

Carlson, L. E., Waller, A., Groff, S. L., Giese-Davis, J. & Bultz, B. D. What Goes up does not always come down: Patterns of distress, physical and psychosocial morbidity in people with cancer over a one year period. Psycho-Oncology 22, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2068 (2011).

Caruso, R., Nanni, M. G., Riba, M., Sabato, S. & Grassi, L. The burden of psychosocial morbidity related to cancer: Patient and family issues. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 29, 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2017.1288090 (2017).

Bubis, L. D. et al. Symptom burden in the first year after Cancer diagnosis: An analysis of patient reported outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 1103–1111. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.76.0876 (2018).

Singer, S. Psychosocial impact of cancer. In Psycho-Oncology: Recent Results in Cancer Research (eds. Goerling, U. & Mehnert, A.) (Springer, 2018).

Bodenmann, G.. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In Couples Coping with Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping (eds. Kayser, K., Bodenmann, G., Revenson, T. A.). 73–95 (American Psychological Association, 2005).

Regan, T. W. et al. Couples coping with cancer: Exploration of theoretical frameworks from dyadic studies. Psycho-Oncology 24, 1605–1617. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3854 (2015).

Jacobs, J. M. et al. Distress is interdependent in patients and caregivers with newly diagnosed incurable cancers. Ann. Behav. Med. 51, 519–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9875-3 (2017).

Rottmann, N. et al. Dyadic coping within couples dealing with breast cancer: A longitudinal, population-based study. Health Psychol. 34, 486–495. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000218 (2015).

Baucom, D. H., Porter, L. S., Kirby, J. S. & Hudepohl, J. Couple-based interventions for medical problems. Behav. Ther. 43, 61–76 (2012).

Bodenmann, G. A systemic-transactional conceptualization of stress and coping in couples. Swiss J. Psychol. 54, 34–49 (1995).

Falconier, M. K., Jackson, J. B., Hilpert, P. & Bodenmann, G. Dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 42, 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.002 (2015).

Traa, M. J., De Vries, J., Bodenmann, G. & Den Oudsten, B. L. Dyadic coping and relationship functioning in couples coping with cancer: A systematic review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 20(1), 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12094 (2015).

Bodenmann, G. et al. Effects of stress on the social support provided by men and women in intimate relationships. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1584–1594 (2015).

Meier, F., Cairo Notari, S., Bodenmann, G., Revenson, T. A. & Favez, N. We are in this together—Aren’t we? Congruence of common dyadic coping and psychological distress of couples facing breast cancer. Psychooncology 28(12), 2374–2381. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5238 (2019).

Lyons, K. S. & Lee, C. S. The theory of dyadic illness management. J. Fam. Nurs. 24, 8–28 (2018).

Rottmann, N. et al. Dyadic coping within couples dealing with breast cancer: A longitudinal, population-based study. Health Psychol. 34, 486–495 (2015).

Stefanut, A. M., Vintila, M. & Sarbescu, P. Perception of disease, dyadic coping and the quality of life of oncology patients in the active treatment phase and their life partners: Study protocol of an approach based on the actor-partner interdependence model. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 30, e13374 (2021).

Falconier, M. K. & Kuhn, R. Dyadic coping in couples: A conceptual integration and a review of the empirical literature. Front. Psychol. 10, 571 (2019).

Wong, S. S., George, T. J., Godfrey, M., Le, J. & Pereira, D. B. Using photography to explore psychological distress in patients with pancreatic cancer and their caregivers: A qualitative study. Supp. Care Cancer 27, 321–328 (2019).

Chong, E., Crowe, L., Mentor, K., Pandanaboyana, S. & Sharp, L. Systematic review of caregiver burden, unmet needs and quality-of-life among informal caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer. Supp. Care Cancer. 31(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07468-7 (2022).

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357 (2007).

Francis, J. J. et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 25, 1229–1245 (2010).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa (2006).

Kiger, M.E. & Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 42 (8), 846–854 https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030 (2020).

Liu, W., Lewis, F. M., Oxford, M. & Kantrowitz-Gordon, I. Common dyadic coping and its congruence in couples facing breast cancer: The impact on couples’ psychological distress. Psychooncology. 33(3), e6314. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6314 (2024).

Guerrero-Torrelles, M., Monforte-Royo, C., Rodríguez-Prat, A., Porta-Sales, J. & Balaguer, A. Understanding meaning in life interventions in patients with advanced disease: A systematic review and realist synthesis. Palliat. Med. 31(9), 798–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316685235 (2017).

Porter, L. S. et al. A randomized pilot trial of a videoconference couples communication intervention for advanced GI cancer. Psychooncology 26(7), 1027–1035 (2017).

Yasmin, N. & Riley, G. A. Psychological intervention for partners poststroke: A case report. NeuroRehabilitation. 47(2), 237–245 (2020).

Zemp, M. et al. Couple relationship education: A randomized controlled trial of professional contact and self-directed tools. J. Fam. Psychol. 31(3), 347–357 (2017).

Bannon, S. M., Grunberg, V. A. & Reichman, M. Thematic analysis of dyadic coping in couples with young-onset dementia. JAMA Netw. Open 4(4), e216111 (2021).

Landolt, S. A., Weitkamp, K., Roth, M., Sisson, N. M. & Bodenmann, G. Dyadic coping and mental health in couples: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 106, 102344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102344 (2023).

Yang, F. et al. The experiences of family resilience in patients with permanent colostomy and their spouses: A dyadic qualitative study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 70, 102590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2024.102590 (2024).

Gremore, T. M. et al. Couple-based communication intervention for head and neck cancer: A randomized pilot trial. Supp. Care Cancer 29, 3267–3275 (2021).

Kor, P., Leung, A. & Parial, L. L. Are people with chronic diseases satisfied with the online health information related to COVID-19 during the pandemic?. J. Nurs. Scholar. 53(1), 75–86 (2021).

Brosseau, D. C., Peláez, S., Ananng, B. & Körner, A. Obstacles and facilitators of cancer-related dyadic efficacy experienced by couples coping with non-metastatic cancers. Front. Psychol. 14, 949443. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.949443 (2023).

Umbrello, M. et al. Music therapy reduces stress and anxiety in critically ill patients: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 85(8), 886–898 (2019).

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P. & Greene, P. A. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 59, 52–60 (2018).

Carpenter, J. K. et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress. Anxiety 35(6), 502–514 (2018).

Thomson, M. D., Wilson-Genderson, M. & Siminoff, L. A. Cancer patient and caregiver communication about economic concerns and the effect on patient and caregiver partners’ perceptions of family functioning. J. Cancer Surviv. 18(3), 941–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01341-0 (2024).

Bodschwinna, D. et al. Couples coping with hematological cancer: Support within and outside the couple—Findings from a qualitative analysis of dyadic interviews. Front. Psychol. 13, 855638. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.855638 (2022).

Palmer Kelly, E., Meara, A., Hyer, M., Payne, N. & Pawlik, T. M. Understanding the type of support offered within the caregiver, family, and spiritual/religious contexts of cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 58, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman (2019).

Greer, J. A., Applebaum, A. J., Jacobsen, J. C., Temel, J. S. & Jackson, V. A. Understanding and addressing the role of coping in palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 38(9), 915–925. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00013 (2020).

Vodermaier, A. & Linden, W. Social support buffers against anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with cancer only if support is wanted: A large sample replication. Supp. Care Cancer 27, 2345–2347 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. Peer support interventions for breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 174(2), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5033-2 (2019).

Adlard, K. N. et al. Peer support for the maintenance of physical activity and health in cancer survivors: The PEER trial—A study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 19(1), 656. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5853-4 (2019).

Rodin, G., An, E., Shnall, J. & Malfitano, C. Psychological interventions for patients with advanced disease: Implications for oncology and palliative care. J. Clin. Oncol. 38(9), 885–904. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00058 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the hospital that provided the research site. We also would like to sincerely thank all patients and spouses who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors had a substantial contribution to the manuscript. Bo Zhang: Conceptualisation, Study design, Data collection, Data analysis, Data interpretation, Writing—original draf, Review and editing, Final approval; Qigui Xiao and Jingtao Gu: Conceptualisation, Study design; Qingyong Ma: Study design, Review and editing; Liang Han: Study design, Review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Xiao, Q., Gu, J. et al. A qualitative study on the disease coping experiences of pancreatic cancer patients and their spouses. Sci Rep 14, 18626 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69599-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69599-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The psychosocial impact of pancreatic cancer on caregivers: a scoping review

BMC Cancer (2025)

-

Supportive Care Needs and Related Interventions in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer and Their Informal Caregivers: A Scoping Review

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2025)