Abstract

The present study aims to investigate the low-energy consumption and high-efficiency removal of arsenic from aqueous solutions. The designed adsorbent Fe/TBC was synthesized by impregnating iron on torrefaction henequen fibers. Isothermal adsorption experiments indicated maximum adsorption capacities of 7.30 mg/g and 8.98 mg/g for arsenic(V) at 25.0 °C and 40.0 °C, respectively. The interference testing showed that elevated levels of pH, HCO3− concentration, and humic acid content in the solution could inhibit the adsorption of arsenic by Fe/TBC. Characterization of the adsorbent before and after adsorption using FTIR and SEM–EDS techniques confirmed arsenic adsorption mechanisms, including pore filling, electrostatic interaction, surface complexation, and H-bond adhesion. Column experiments were conducted to treat arsenic-spiked water and natural groundwater, with effective treatment volumes of 550 mL and 8792 mL, respectively. Lastly, the life cycle assessment (LCA) using OpenLCA 2.0.3 software was performed to treat 1 m3 of natural groundwater as the functional unit. The results indicated relatively significant environmental impacts during the Fe/TBC synthesis stage. The global warming potential resulting from the entire life cycle process was determined to be 0.8 kg CO2-eq. The results from batch and column experiments, regeneration studies, and LCA analysis indicate that Fe/TBC could be a promising adsorbent for arsenic(V).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arsenic (As) contamination in water sources is a pressing global environmental and public health concern1. As is pervasive in the natural environment and can enter water bodies through natural processes like rock weathering and erosion or human activities such as agriculture and mining2. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established a stringent permissible level of 10 μg/L for As in drinking water. Prolonged exposure to elevated levels of As can lead to severe health issues, including skin lesions, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurological disorders3.

Various techniques have been developed to remove As from water, including chemical precipitation, coagulation-flocculation, ion exchange, membrane filtration, and adsorption4. Among these, adsorption using modified biochar has gained attention for its efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness5,6,7,8,9.

Temperature-dependent thermal processes for biomass conversion include drying (25–150 °C), torrefaction (150–300 °C), pyrolysis (300–600 °C), and gasification (> 600 °C)10. Torrefaction is primarily a thermal pretreatment technique11 that has been shown to enhance As(V) removal efficiency when applied to betel nut shell pyrolysis biochar12. However, in recent years, torrefaction biochar (TBC) has garnered more attention due to its low energy consumption, ease of handling, and higher abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups13,14,15. Li et al. and Hu et al. reported the effective adsorption of uranium, methylene blue, and certain toxic metal ions from wastewater using TBC16,17. Zhang et al. in a literature analysis, summarized that biochar prepared at low temperatures exhibits a higher As adsorption capacity7.

Henequen fibers, a renewable and abundant biomass resource indigenous to Mexico, have demonstrated robust environmental credentials. Vargas et al. directly employed henequen fibers as adsorbents to remove methylene blue and reactive black 5 dyes from water18. Additionally, Dizbay-Onat et al. effectively adsorbed volatile organic compounds using activated carbon derived from sisal fibers19. Researchers have also illustrated the capacity of henequen fiber-based products to efficiently adsorb and eliminate Pb(II) and Cd(II) ions, as well as rifampin from aqueous solutions20,21,22. Despite their remarkable attributes exhibited, henequen fibers have been scarcely investigated for their ability to adsorb anionic heavy metals like As in aquatic environments.

Iron-based materials are often combined with biochar for As adsorption due to their high adsorption capacity, cost-effectiveness and reactivity23,24. This study initially pioneers the use of FeCl3-impregnated TBC (Fe/TBC) derived from henequen fibers for the removal of As(V) in aqueous solution. The principal objectives of this study are to (i) investigate the effectiveness and mechanisms of Fe/TBC in adsorbing As from aqueous solution, (ii) evaluate the practical application potential of Fe/TBC for the removal of As from natural groundwater through small-scale fixed-bed adsorption experiments, and (iii) conduct a life cycle assessment of Fe/TBC treating 1 m3 of As-contaminated groundwater.

Materials and methods

Chemical reagents

Analytical grade sodium arsenate dibasic heptahydrate (Na2HAsO4·7H2O), ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), sodium chloride (NaCl), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl2·2H2O), sodium phosphate (Na3PO4), magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2·6H2O), ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4), humic acid sodium salt and nitric acid (HNO3, 64–66% w/w) were obtained from Environmental Laboratory, Engineering Division, Universidad de Guanajuato. All required solutions in the study were prepared from analytical reagents with deionized water.

TBC feedstocks and groundwater

TBC feedstocks, subsequently referred as henequen fibers (Agave fourcroydes), were procured from a distributor and originated from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. The henequen fibers were first washed with tap water to remove impurities, then washed with deionized water, followed by drying in an oven at 60.0 °C for 24 h. The dried henequen fibers were then cut into small pieces of 0.5–1 cm in size. The samples were then encapsulated for later use.

As-contaminated groundwater was collected from a well in Guanajuato, Mexico. The collected groundwater was stored in capped polyethylene bottles and promptly brought back to the laboratory for storage under low-temperature and light-proof conditions. Fundamental characteristics, as well as the specific cations and anions contained in the natural groundwater, are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Specifically, the pH was 7.6, and the concentration of As was 24.10 µg/L.

Preparation of Fe/TBC composites

The synthesis of Fe/TBC followed common ultrasound treatment25 and in situ precipitation methods26 for Fe-modified biochar. Supplementary Fig. S1 presents the preparation processes of the composites of TBC impregnated with Fe. Henequen fiber feedstocks were gathered and compacted into cylindrical modules. Each module had a radius of 2 cm and a thickness of 0.5 cm, achieved through compression utilizing a hydraulic press operating at a pressure of 27 MPa. Then, the prepared henequen fiber modules were placed in a muffle furnace for torrefaction. The torrefaction temperature was set with three stages successively, which were 120 °C (30 min), 200 °C (60 min), and 260 °C (15 min), with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Finally, the torrefied biomass was washed, dried, and ground through a 20–200 mesh sieve to obtain the TBC fibers.

A simple ultrasound-assisted impregnation method was used to prepare the Fe/TBC composites. Firstly, TBC fibers were immersed in nitric acid (20% v/v) and ultrasonicated at 40 kHz for 30 min to enhance the hydrophilicity of the TBC surface, and then they were dried thoroughly27. Next, 2 g of TBC and 4.8 g of FeCl3·6H2O were mixed in 40 mL of deionized water, and the mixture was subjected to ultrasound treatment at a frequency of 40 kHz for 30 min. The resulting mixture solution was then dried in a 60.0 °C oven for 3 days. Finally, the prepared sample was collected, washed three times with deionized water, and dried to obtain the Fe/TBC.

Characterizations

The crystal phases of the solid samples before and after adsorption were collected on an X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Ka radiation (XRD Ultima IV, Rigaku, Japan). The bulk chemical compositions of the samples were analyzed with X-Ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF NEX CG, Rigaku, Japan). Scanning electron microscope (SEM JSM-6010PLUS/LA, JEOL, Japan) equipped with an X-ray dispersive spectroscopy (EDS X-MaxN, Oxford, UK) system was used to investigate surface components of solid samples before and after adsorption. The concentration of As and Fe in aqueous solutions were determined using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS PinAAcle 900F, PerkinElmer, USA). The specific surface area and pore size distribution were determined using N2 adsorption methods with the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) approach (TriStar II Plus 2.03, Micromeritics, USA). The chemical functional groups were identified using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Tensor 27, Bruker, DEU) in the wavenumber range of 400 cm−1 to 4000 cm−1. The adsorbent surface charge was measured with a zeta potential meter (Zeta-Meter 3.0+, Zeta-Meter Inc., USA).

Batch experiments

The adsorption kinetics were performed by adding 100.0 mg of adsorbent to a conical flask containing 50 mL of 1.0 mg/L As solution. The initial pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.0 with 0.1 M HCl solution and 0.1 M NaOH solution. The flask was placed in an oscillator and shaken at 160 rpm. The operating temperature was set at 25.0 ± 1.0 °C and 40.0 ± 1.0 °C, respectively. About 0.5 mL of solution was collected at specific time intervals. A total of 11 samples were collected from one batch over an 8-h exposure time to determine the amount of remaining As.

In terms of adsorption isotherms, the initial As concentration was set between 1.0 to 50.0 mg/L, and 20.0 mg of adsorbent was added into a centrifugal tube containing 10 mL of the As-spiked solution. The centrifuge tubes were fixed horizontally into the oscillator and shaken at 160 rpm for 72 h, with operating temperatures of 25.0 ± 1.0 °C and 40.0 ± 1.0 °C. The initial pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.0 using 0.1 M HCl solution and 0.1 M NaOH solution.

To investigate the influence of pH and adsorbent dose on As adsorption, the pH value and adsorbent dose were set from 3.0 to 11.0, and 0.5 to 3.0 g/L, respectively. The effect of other anions, cations, and organic matter on the As adsorption was determined by adding NaHCO3, Na2SO4, Na3PO4, CaCl2, MgCl2, and humic acid. The initial As concentration was set at 1.0 mg/L, and the adsorbent addition was 2.0 g/L. The working temperature was 25.0 ± 1.0 °C. Each collected sample of the solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm polyethersulfone membrane. After the adsorption process was completed, the removal efficiency and adsorption capacity (\(q_{e}\)) were then calculated using the following equations:

where \(C_{0}\) is the adsorbate initial concentration, \(C_{e}\) is the adsorbate remaining concentration after the adsorption, \(m\) is the mass of the adsorbent, and \(V\) denotes the solution volume.

Regeneration study

Three adsorption–desorption cycles were performed to assess the regeneration capacity and recovery efficiency of Fe/TBC. Initially, As adsorption was carried out in 50 mL polyethylene centrifuge tubes containing 25 mL of 1.0 mg/L As(V) solution and 50.0 mg of Fe/TBC, adjusted to a pH of 7.0. After 72 h of shaking under 25.0 ± 1.0 °C, the Fe/TBC was collected through filtration, washed with deionized water, and oven-dried for subsequent regeneration experiments. The As-loaded Fe/TBC was then desorbed using 25 mL of four extractants: 0.1 M NaHCO3, 1 M NaCl, 0.05 M ((NH4)2SO4), and 0.1 M HNO328. Each desorption experiment was conducted for 24 h at a temperature of 25.0 ± 1.0 °C. Then, the desorbed Fe/TBC was recovered through filtration, washing, and drying. After each adsorption–desorption cycle, the filtrate was collected for the subsequent determination of As and Fe concentrations. The desorption efficiency of As can be calculated using the following equation26:

where \(C_{des}\) and \(C_{ads}\) are the desorbed amount (mg/L) of As in the solution and the adsorbed amount of As by Fe/TBC, respectively.

Column experiments

The column experiments were carried out with reference to American Society for Testing Materials 6586-03 (Standard Practice for the Prediction of Contaminant Adsorption On GAC In Aqueous Systems Using Rapid Small-Scale Column Tests)29. The effective length of the fixed-bed column filled with adsorbent (3.0 g for one column) was 100 mm, the diameter was 10 mm. Glass wool at both ends of the fixed-bed column was used to distribute the flow. Peristaltic pumps delivered As-contaminated natural groundwater and As-spiked water down-flow into the column at a constant flow rate. The empty bed contact time was set to 5 min, and the flow rate was 1.57 mL/min.

LCA analysis

The OpenLCA 2.0.3 software was utilized to perform the life cycle assessment. The function unit for the assessment was defined as treating 1 m3 of As-contaminated groundwater. The entire life cycle consisted of TBC production, Fe/TBC synthesis, and groundwater treatment stages. The ReCiPe Midpoint (H) LCA method was employed to interpret potential environmental impacts30. Supplementary Fig. S2 illustrates the system boundary and input/output flows in different processes during the life cycle assessment. The data for this study were scaled up from laboratory experiment results. The LCA inventory was obtained from the Ecoinvent 3.8 and AGRIBALYSE 3.1 databases. Detailed information on the LCA inventory database is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical error analysis

The coefficient of determination (R2) is commonly used for evaluating adsorption model fit quality, but it can lead to ambiguities with incomplete data sets31. In this study, root mean square error (RMSE) was used alongside R2 to further confirm the model’s fit accuracy to the experimental data. A higher R2 value, closer to 1, indicates that the model explains more variance in the data, suggesting a better fit. A lower RMSE value signifies more accurate predictions with smaller errors. The standard error of the RMSE was calculated with the following equation32:

where \(q\left( i \right)_{exp}\) is the experimental adsorption capacity (mg/g), \(q\left( i \right)_{cal}\) is the theoretical adsorption capacity calculated by the model (mg/g), and n is the number of data points.

Results and discussion

Fe/TBC properties

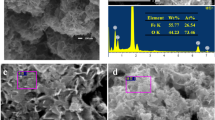

Figure 1 presents the SEM images and EDS scanning results of biochar fibers. The surface of TBC fibers exhibits a uniform and smooth morphology (Fig. 1a). Upon examining the cross-section in Fig. 1b, the internal pore structure of TBC fibers is intricate, featuring a well-developed network of fine fibers. Following the iron modification, Fig. 1c displays a considerable quantity of irregular crystalline particles precipitating onto the TBC fiber surface. The inset image (Fig. 1e) in Fig. 1c provides detailed views of the crystalline particles. EDS scanning analysis of the Fig. 1e indicates that the Fe component reaches 10.84%, while the predominant elements consist of C and O. Supplementary Table S3 compiles the XRF analysis results for TBC, Fe/TBC, and Fe/TBC after As adsorption, indicating a comprehensive Fe content of 4.16% in Fe/TBC. Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4 compare the XRD patterns for TBC and Fe/TBC and substantiate that the iron modification of TBC results in the formation of magnesian ferroan, lepidocrocite, and feroxyhite minerals in Fe/TBC. Lepidocrocite and feroxyhite were recognized for their specific affinity for As adsorption33,34.

The specific surface area, average pore diameter and total volume in pores of TBC before and after HNO3 treatment and Fe/TBC are presented in Supplementary Table S4. Due to the corrosion of the micropore walls in biochar by the acid, the BET surface area and total pore volume of TBC significantly decrease after HNO3 treatment35. Owing to infusion with Fe particles, the BET surface area and total pore volume exhibit increases from 0.5173 m2/g and 0.00122 cm3/g for TBC after HNO3 treatment to 2.2317 m2/g and 0.00391 cm3/g for Fe/TBC, respectively36.

Adsorption kinetics

The adsorption kinetics of As onto Fe/TBC were examined under temperatures of 25.0 °C and 40.0 °C, as depicted in Fig. 2a. Over an 8-h contact period, Fe/TBC demonstrated the ability to remove approximately 80% of As from the aqueous solution. During the initial stage of adsorption, the reaction proceeded rapidly due to the abundance of adsorption sites. After 30 min, the adsorption efficiency reached 65%, yet the adsorption process slowed considerably. It is noteworthy that within the initial 10 min, the adsorption rate at 25.0 °C was faster than at 40.0 °C. This phenomenon could be attributed to the dominance of physical adsorption in the early stages of adsorption. At the lower temperature, non-specific adsorption prevailed, and the adsorption rate was relatively faster. As the adsorption process progressed, at higher temperatures, the molecular energy was sufficient to overcome activation energy barriers, thereby enhancing the propensity for chemical adsorption. Consequently, chemical adsorption gradually superseded physical adsorption and dominated the later stage of adsorption37.

To further evaluate the adsorption kinetics, pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), and Elovich adsorption models were employed to fit the adsorption processes. The fitting curves are shown in Fig. 2a. The equations of the PFO model (Eq. (5)), the PSO model (Eq. (6)), and the Elovich model (Eq. (7)) are presented as follows:

where \(t\) (min) is the adsorption time, \(q_{e}\) (mg/g) is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium, \(q_{t}\) (mg/g) is the adsorbed amount of the adsorbate at time t, \(k_{1}\) (min−1) is PFO rate constant, \(k_{2}\) (g·mg−1·min−1) is PSO rate constant, \(a\) (mg·g−1·min−1) is the initial adsorption rate constant of the Elovich model, and \(b\) (g·mg−1) is the desorption rate constant of the Elovich model.

The model fitting parameters are listed in Supplementary Table S5. The adsorption process of As by Fe/TBC was well-simulated by the Elovich model, with fitting coefficients of 0.977 and 0.974 at temperatures 25.0 °C and 40.0 °C, respectively. Additionally, the RMSE values were the lowest among all tested models, further demonstrating the good fit of the Elovich model. The alignment between the adsorption kinetics data and the Elovich model suggested non-uniformity on the adsorbent surface, with the activation energy increasing as the adsorption time prolonged38. At 25.0 °C, the Elovich model's initial adsorption rate constant (\(a\)) was 0.256 g mg−1 min−1, compared to 0.206 g mg−1 min−1 at 40.0 °C. This was supported in the early stages of As adsorption on Fe/TBC, where lower temperature was associated with a faster adsorption rate. Additionally, the calculated \(q_{e}\) results under PSO and PFO models were slightly lower than the experimental values, being 0.417 mg/g at 25.0 °C and 0.419 mg/g at 40.0 °C.

Adsorption isotherms

Adsorption isotherm models were employed to fit equilibrium adsorption capacities at different initial As concentrations. In this study, Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were used for data fitting, and the fitting curves are shown in Fig. 2b. The equations of the Langmuir isotherm model and the Freundlich isotherm model are summarized as follows:

where \(q_{e}\) (mg/g) is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium, \(q_{m}\) (mg/g) is the maximum adsorption capacity, \(C_{e}\) (mg/L) is the As concentration in the solution at equilibrium, \(k_{L}\) is the Langmuir adsorption constant, and \(k_{F}\) and n are the Freundlich adsorption constants.

Supplementary Table S6 summarizes the calculated parameters for both models. The Freundlich model (25.0 °C, R2 = 0.934, RMSE = 0.606; 40.0 °C, R2 = 0.966, RMSE = 0.564) exhibited better fitting performance than the Langmuir model (25.0 °C, R2 = 0.903, RMSE = 0.734; 40.0 °C, R2 = 0.903, RMSE = 1.696). The better fit of the experimental data with the Freundlich model implies that the adsorption of As by Fe/TBC is a reversible and non-ideal process. Furthermore, the adsorption intensity parameter 1/n in the Freundlich model is greater than 0 and less than 1, indicating that the adsorption process is favorable39. The Langmuir model yielded maximum adsorption capacities of 7.30 mg/g and 8.98 mg/g at 25.0 °C and 40.0 °C, respectively. Consistent with findings by Carneiro et al. and Singh et al., an increase in the As adsorption capacity was observed at elevated temperatures24,40. This temperature-dependent enhancement in maximum adsorption capacity further supports the characterization of the As adsorption process by Fe/TBC as endothermic. In addition, Table 1 summarizes the maximum adsorption capacities of iron-modified biochar materials for As removal in recent studies. The adsorption capacity of As by Fe/TBC either matches or exceeds that of the majority of iron-modified biochars.

Effect of adsorbent dose, pH, co-existing ions and humic acid

Figure 3a illustrates the adsorption performance of Fe/TBC and TBC for 1.0 mg/L of the As-spiked solutions. A dosage of 0.5 g/L of Fe/TBC only can remove As from the solution by 79%. However, at a Fe/TBC dosage of 2.0 g/L, the removal efficiency increased to 98%. The enhanced adsorption efficiency can be attributed to sufficient adsorption sites with the increase of adsorbent dosage. Conversely, using TBC, the maximum removal efficiency for As from the aqueous solution was only 33%. Iron impregnation significantly improved the adsorption capacity of TBC for As. Furthermore, the adsorption efficiency of the raw henequen fiber at the dosage of 1.0 g/L was merely 11%.

The solution’s pH significantly influences both adsorbate states and adsorbent surface charges. Figure 3b depicts the removal efficiency of As from aqueous solutions at pH values ranging from 3.0 to 11.0, employing 1.0 g/L and 2.0 g/L dosages of Fe/TBC. Generally, the As removal efficiency increased slightly from pH 3 to 6 and then gradually declined. This trend parallels the findings of Hongbin et al. in their study on As removal using charred granulated attapulgite-supported hydrated iron oxide45. The As removal efficiencies were 97–73% (Fe/TBC = 1.0 g/L) and 98–85% (Fe/TBC = 2.0 g/L) in the pH range of 6.0–8.0, respectively. Amen et al. provided a comprehensive overview of As adsorption on biochar-based adsorbents, highlighting its pH-dependent nature46. Supplementary Fig. S5 shows the Zeta potential of Fe/TBC as a function of pH. The Zeta potential is gradually decreases as the pH increases. The pH for the point of zero charge (pHpzc) approximately is 3.7. This result is consistent with the finding of Wei et al. on iron oxide nanoneedle array-decorated biochar fibers25. When the pH < pHpzc, Fe/TBC adsorbs As through electrostatic attraction due to the positively charged adsorbent surface. At a higher pH (pH > pHpzc), the Zeta potential becomes negative, reflecting a shift to the negative surface charge of Fe/TBC. This change reduces the electrostatic attraction, leading to the adsorption of As by Fe/TBC primarily occurring through chemisorption. But to be noticed, the pHpzc only represents the overall average charge state of the Fe/TBC surface, while adsorption occurs at the microscopic level where As directly interacts with Fe/TBC. The adsorption of As is still largely influenced by the surface of iron (hydro)oxides, particularly by the extent of exposed reactive crystal facets47,48. At pH 10 and 11, the As removal efficiency decreased to 41% and 34%, respectively, at a Fe/TBC dosage of 1.0 g/L. However, with an adsorbent dosage of 2.0 g/L, the removal efficiency remained high at 76% and 60%, respectively. This could have occurred because the higher adsorbent dosage provided additional chemisorption sites in the alkaline environment25.

To simulate the practical application capability of Fe/TBC, this study investigated the influence of magnesium (Mg2+), calcium (Ca2+), bicarbonate (HCO3−), sulfate (SO42−), phosphate (PO43−), and humic acid. The results are presented in Fig. 3c. Magnesium, calcium, and sulfate exhibited minimal impact on As removal. However, the presence of PO43−, due to its electron structure similarity to As, significantly interfered with As adsorption49. Even with a phosphate ion concentration as low as 0.25 mg/kg, the removal efficiency of As decreased to 82%. Bicarbonate ions, owing to their negative charge, also adversely affected As retention50. With 400.0 mg/kg bicarbonate concentration in the solution, the As removal efficiency dropped to 62%. Consistent with the findings of Saldaña-Robles et al., humic acid was shown to inhibit As adsorption51. In this study, a humic acid concentration of 5.0 mg/L had no impact on As removal. However, as the humic acid concentration increased to 20.0 mg/L, the As removal efficiency decreased to 83%. The presence of abundant humic acid occupying adsorption sites on the Fe/TBC surface is implicated in hindering As adsorption.

Regeneration of Fe/TBC

Figure 4 presents the results of Fe/TBC's regeneration abilities over three adsorption–desorption cycles. Fe leaching from the adsorbent was also monitored during all adsorption and desorption processes. Overall, the As removal efficiency of Fe/TBC gradually decreases after each regeneration cycle. The As adsorption efficiencies of Fe/TBC after three regeneration cycles using 0.1 M HNO3 (Fig. 4a), 0.05 M (NH4)2SO4 (Fig. 4b), 0.1 M NaHCO3 (Fig. 4c), and 1 M NaCl (Fig. 4d) decreased from 79%, 65%, 85%, and 68% to 47%, 57%, 37%, and 44%, respectively. The 0.1 M HNO3 and 0.1 M NaHCO3 regenerated Fe/TBC better during the first and second cycles, probably due to their higher desorption efficiency for As-loaded Fe/TBC. However, during the third regeneration cycle with 0.1 M NaHCO3, the significant loss of Fe weakened the binding between Fe/TBC and As, resulting in a desorption efficiency of 89% but an adsorption efficiency of only 37%. The 0.05 M (NH4)2SO4 caused minimal Fe dissolution and adsorbent damage during Fe/TBC regeneration processes, and maintained a 57% As adsorption capacity in the third cycle. The 1 M NaCl showed almost no desorption capability for As-loaded Fe/TBC, yet the adsorption capacity remained above 44% after three regeneration cycles. The desorption capacity of As-loaded Fe/TBC using 1 M NaCl solution was only 1–13%. However, even Fe/TBC adsorbing all the As from the solution (maximum capacity of 0.5 mg/g), which remains significantly lower than the Langmuir adsorption capacity (7.30 mg/g at 25.0 °C), the regenerated Fe/TBC could continue to adsorb As in subsequent cycling processes. This finding aligns with the study of Alchouron et al. on regenerating iron oxide-modified bamboo biochar for As removal52.

The dissolved Fe content of the filtrate after initial adsorption was 3.4 mg/L. This result closely resembles the leaching of Fe observed in studies utilizing iron-modified biochar for arsenic treatment24,52. However, as observed in Fig. 4a,c, the leaching concentration of Fe during the initial desorption process reached 12.1 mg/L and 12.3 mg/L under the effect of 0.1 M HNO3 and 0.1 M NaHCO3, respectively. This is because high acid or alkaline solutions facilitate the dissolution of Fe ions from iron oxides28,53. In contrast, the concentration of dissolved Fe in the adsorption–desorption cycles under the effects of 0.05 M (NH4)2SO4 and 1 M NaCl was only 0.1–1.0 mg/L and 0.1–3.0 mg/L, respectively.

Adsorption mechanism

Biochar adsorbs As through diverse mechanisms, including ion exchange, redox reaction, surface complexation, precipitation, electrostatic interactions, and pore filling15. Isotherm and kinetic adsorption studies have substantiated that, Fe/TBC predominantly relies on physical adsorption for the uptake of As from aqueous solutions in the initial stage, then transitions to chemical adsorption in the subsequent stages. Figure 5 depicts the comparative characterization of Fe/TBC before and after As adsorption and provides further insights into the underlying adsorption mechanisms of As onto Fe/TBC.

Figure 5a displays the FTIR spectra of TBC, Fe/TBC and As-loaded Fe/TBC. The peaks observed at 3398 cm−1, 2917 cm−1, and 666 cm−1 in TBC spectrum correspond to the stretching vibrations of –OH, –CH2, and C–C-C, respectively41,54. The peaks at 1729 and 1634 cm-1 are attributed to the presence of –C=O vibration54,55. Distinct peaks in the range of 1429–1032 cm−1 indicate groups of –C–O, –C=C, and C=C–C40,54. The –OH groups in biochar can adsorb As through hydrogen bonding and also act as Lewis bases, facilitating the formation of chemical bonds with As species. The presence of –CH2 increases the surface polarity of biochar, facilitating the electrostatic adsorption of As to the positively charged adsorbent surface. Furthermore, the double bonds in –C=O and –C=C introduce unsaturation on the biochar surface, enhancing its reactivity towards As44. The observed slight shifts and intensity variations in the peaks corresponding to these functional groups in the spectra before and after adsorption suggest their involvement in As species complexation. The Fe–O vibration bands are observed at 518 cm−1 and 520 cm−1 in the spectra of Fe/TBC and As-loaded Fe/TBC56,57. This aligns with XRD patterns of Fe/TBC (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4), which confirms the presence of weakly crystalline iron oxides on the Fe/TBC surface. Additionally, the weak O–As–O stretching vibration observed at 480 cm−1 in the spectrum of Fe/TBC loaded with As confirms the complexation between As and surface functional groups of Fe/TBC58.

In Fig. 5b,c, the combined SEM–EDS technique was employed to spatially resolve the surface chemical composition of Fe/TBC subsequent to As adsorption. Figure 5b illustrates the emergence of fiber cracks within Fe/TBC, where the As concentration reaches 0.2%, significantly surpassing the mean value of 494 mg/kg in Fe/TBC with As loaded. And the Supplementary Table S4 summarizes that the BET surface area and total pore volume noticeably reduce from 2.2317 to 1.1056 m2/g, and from 0.00391 to 0.00158 cm3/g, respectively. The decrease in BET surface area and alterations in pore structures suggest that physical adsorption by pore filling, dictated by van der Waals forces, contributes to the As adsorption9,15. Furthermore, Fig. 5c demonstrates the adsorption efficacy of iron oxides precipitated onto the Fe/TBC surface. The corresponding crystal-like structure contains up to 0.48% As. Precipitation of crystalline rich in Fe and As, combined with FTIR spectra of As-loaded Fe/TBC, suggests that the adsorption of As by Fe/TBC proceeds through the complexation of an inner sphere ligand between the arsenate and the hydroxyl group associated with Fe3+ in the iron oxide59. In summary, the predominant mechanisms driving the adsorption of As by Fe/TBC comprise pore filling, surface complexation, H-bond adhesion, and electrostatic attraction, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S6.

Column experiments

Column experiments were conducted to treat As-spiked water (CAs = 1000 µg/L) as well as natural groundwater (CAs = 24.10 µg/L). Figure 6 depicts breakthrough curves for the removal of As in column experiments. The effective treatment volumes for As-spiked water and natural groundwater were 550 mL and 8792 mL, respectively, when the breakthrough point was set at the WHO permissible level (10 µg/L). The calculated effective column As adsorption density (qcolumn) for As-spiked water at the breakthrough point of 10 μg/L was 183 µg/g. This result surpasses the 0.09 mg/g obtained by Yin et al. using Fe-modified charred GAP for As removal45. However, due to the elevated pH (7.6) and potential ion interferences, the qcolumn of Fe/TBC for natural groundwater is only 71 μg/g. The Thomas model has proven effective in fitting the adsorption of metals in biochar columns. Equation (10) provides the nonlinear expression for the Thomas model60

where \(C_{t}\) is the effluent concentration at a different time (μg/L), \(C_{0}\) is the influent concentration (μg/L), \(K_{TH}\) is the rate constant (min−1·mL/mg−1), \(Q\) is the flow rate (mL/min), \(q_{0}\) is the equilibrium uptake (μg/g), \(m\) is the mass of adsorbent (g), and \(V_{eff}\) is the effluent volume (mL).

The fitting curves for As-spiked water and natural groundwater using the Thomas model are presented in Fig. 6a,b, respectively. Supplementary Table S7 shows that the fitting correlation coefficients (R2) are both higher than 0.95. The good fit to the Thomas model suggests that the primary driving force related to adsorption is the concentration gradient. The adsorption process is governed by mass transfer at the interface60,61. Meanwhile, the As-spiked water exhibits a column equilibrium adsorption capacity (\(q_{0}\)) of 366 µg/g, which is very close to the adsorption capacity at kinetic equilibrium but markedly lower than the 10,832 µg/g observed in natural groundwater. This discrepancy is ascribed to a sharp reduction in available adsorption sites at higher As concentrations, leading to a significant decrease in the saturation capacity of Fe/TBC60,62.

LCA interpretation

The environmental impacts associated with TBC preparation, Fe/TBC synthesis, and groundwater treatment processing stages were categorized into 18 indicators utilizing the ReCiPe Midpoint (H) LCA method. But within the present study, a set of ten critical environmental impact indicators has been identified for presentation. These encompass fine particulate matter formation, fossil resource scarcity, freshwater ecotoxicity, global warming, human carcinogenic toxicity, human non-carcinogenic toxicity, ozone formation (human health), ozone formation (terrestrial ecosystems), terrestrial acidification, and terrestrial ecotoxicity. Figure 7 depicts the relative environmental impact analysis results for 1 m3 As-contaminated groundwater treatment with Fe/TBC. It reveals that the TBC preparation exhibits a relatively minor environmental impact, whereas the synthesis of Fe/TBC imposes the highest burden on the environment. Specifically, in the indicators of human non-carcinogenic toxicity, terrestrial acidification, and fossil resource scarcity, the contribution rates during the Fe/TBC synthesis stage reach 79%, 84%, and 92%, respectively.

Supplementary Table S8 summarizes the absolute environmental impact analysis results for treating 1 m3 of As-contaminated groundwater with Fe/TBC. The global warming potential resulting from the entire life cycle process of treating 1 m3 of groundwater with Fe/TBC is determined to be 0.8 kg CO2-eq. Previous LCA analyses of biochar production and environmental application reported both negative values (CO2-eq sequestrations) and positive values (CO2-eq emissions)63. Due to variations in functional units and system boundaries, direct comparisons of CO2 emission data for individual cases are impractical. However, with reference to the average emissions of 0.46 and 0.38 kg CO2-eq/m3 from US water and wastewater utilities64. The removal of As from groundwater using Fe/TBC in this study presents a relatively high level of carbon emissions. The Sankey diagram in Supplementary Fig. S7 illustrates the specific flows and intensities of CO2 emissions from the LCA system. The application of HNO3 is identified as exerting the greatest impact on the global warming indicator, contributing 76.32% to CO2 emissions from all flows. Therefore, alternative technological pathways need to be explored to improve the process of TBC fibers acidification, aiming for carbon neutrality.

Conclusion

Biochar produced through high-temperature pyrolysis under N2 atmosphere is commonly studied for adsorbing hazardous substances. However, this study successfully validates that biochar derived from the torrefaction of henequen fibers also exhibits excellent adsorption effectiveness for As in water bodies. Kinetic adsorption experiments revealed that the adsorption process was well described by the Elovich model. The Langmuir model yielded maximum adsorption capacities of 7.30 mg/g at 25.0 °C and 8.98 mg/g. The As removal efficiencies of Fe/TBC after three regeneration cycles using four extractants decreased to between 37 and 57%. The adsorption process of Fe/TBC on As initially exhibits dominance of physical adsorption, transitioning to chemical adsorption in later stages. Notably, even in the presence of phosphate and humic acid, the removal efficiency of 2.0 g/L of Fe/TBC for 1.0 mg/L of As solution remains above 80%. However, the presence of 400.0 mg/kg bicarbonate concentration could lead to a drop in As removal efficiency to 62%. In the treatment of natural groundwater, the column equilibrium adsorption capacity reached 10,832 µg/g, emphasizing the practical efficacy of Fe/TBC. Overall, Fe/TBC demonstrates low-energy consumption and minimal carbon emissions, offering promising prospects for addressing As-contaminated groundwater.

Data availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

Bundschuh, J. et al. Global arsenic dilemma and sustainability. J. Hazard. Mater. 436, 129197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129197 (2022).

Rathi, B. S. & Kumar, P. S. A review on sources, identification and treatment strategies for the removal of toxic arsenic from water system. J. Hazard. Mater. 418, 126299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126299 (2021).

Rahaman, M. S. et al. Environmental arsenic exposure and its contribution to human diseases, toxicity mechanism and management. Environ. Pollut. 289, 117940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117940 (2021).

Alka, S. et al. Arsenic removal technologies and future trends: A mini review. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123805 (2021).

Zoroufchi Benis, K., Motalebi Damuchali, A., Soltan, J. & McPhedran, K. N. Treatment of aqueous arsenic—A review of biochar modification methods. Sci. Total Environ. 739, 139750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139750 (2020).

Ok, Y. S., Palansooriya, K. N., Yuan, X. & Rinklebe, J. Special issue on biochar technologies, production, and environmental applications in critical reviews in environmental science & technology during 2017–2021. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 3375–3383. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2021.1990446 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Arsenic removal from water and soils using pristine and modified biochars. Biochar https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-022-00181-y (2022).

Yuan, X. et al. Thermochemical upcycling of food waste into engineered biochar for energy and environmental applications: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.143783 (2023).

Chua, S. F. et al. The emergence of multifunctional adsorbents and their role in environmental remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2020.104793 (2021).

Knapczyk, A., Francik, S., Jewiarz, M., Zawiślak, A. & Francik, R. Thermal treatment of biomass: A bibliometric analysis—The torrefaction case. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/en14010162 (2020).

Vithanage, M. et al. Interaction of arsenic with biochar in soil and water: A critical review. Carbon 113, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2016.11.032 (2017).

Gogoi, D. et al. Effect of torrefaction on yield and quality of pyrolytic products of arecanut husk: An agro-processing wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 242, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.03.169 (2017).

Cahyanti, M. N., Doddapaneni, T. & Kikas, T. Biomass torrefaction: An overview on process parameters, economic and environmental aspects and recent advancements. Bioresour. Technol. 301, 122737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.122737 (2020).

Ong, H. C. et al. Variation of lignocellulosic biomass structure from torrefaction: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111698 (2021).

Lin, S. L., Zhang, H., Chen, W. H., Song, M. & Kwon, E. E. Low-temperature biochar production from torrefaction for wastewater treatment: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 387, 129588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129588 (2023).

Hu, H., Zhang, J., Wang, T. & Wang, P. Adsorption of toxic metal ion in agricultural wastewater by torrefaction biochar from bamboo shoot shell. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130558 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Oxygen-rich biochar from torrefaction: A versatile adsorbent for water pollution control. Bioresour. Technol. 294, 122142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122142 (2019).

Vargas, V. H., Paveglio, R. R., Pauletto, P. D. S., Salau, N. P. G. & Dotto, L. G. Sisal fiber as an alternative and cost-effective adsorbent for the removal of methylene blue and reactive black 5 dyes from aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. Commun. 207, 523–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986445.2019.1605362 (2019).

Dizbay-Onat, M., Floyd, E., Vaidya, U. K. & Lungu, C. T. Applicability of industrial sisal fiber waste derived activated carbon for the adsorption of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Fibers Polym. 19, 805–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-018-7866-z (2018).

Negarestani, M., Farimaniraad, H., Mollahosseini, A., Kheradmand, A. & Shayesteh, H. Facile preparation of sisal-Fe/Zn layered double hydroxide bio-nanocomposites for the efficient removal of rifampin from aqueous solution: Kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies. Int. J. Phytoremediation 25, 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2022.2093834 (2023).

Teklu, T., Wangatia, L. M. & Alemayehu, E. Removal of Pb(II) from aqueous media using adsorption onto polyaniline coated sisal fibers. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 25, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/vnl.21652 (2018).

dos Santos, W. N. L., Cavalcante, D. D., da Silva, E. G. P., das Virgens, C. F. & Dias, F. D. S. Biosorption of Pb(ii) and Cd(ii) ions by agave sisalana (sisal fiber). Microchem. J. 97, 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2010.09.014 (2011).

van Genuchten, C. M., Etmannski, T. R., Jessen, S. & Breunig, H. M. LCA of disposal practices for arsenic-bearing iron oxides reveals the need for advanced arsenic recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14109–14119. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c05417 (2022).

Carneiro, M. A., Pintor, A. M. A., Boaventura, R. A. R. & Botelho, C. M. S. Efficient removal of arsenic from aqueous solution by continuous adsorption onto iron-coated cork granulates. J. Hazard. Mater. 432, 128657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128657 (2022).

Wei, Y. et al. Efficient removal of arsenic from groundwater using iron oxide nanoneedle array-decorated biochar fibers with high Fe utilization and fast adsorption kinetics. Water Res. 167, 115107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2019.115107 (2019).

Rahman, M. A., Lamb, D., Rahman, M. M., Bahar, M. M. & Sanderson, P. Adsorption-desorption behavior of arsenate using single and binary iron-modified biochars: Thermodynamics and redox transformation. ACS Omega 7, 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c04129 (2022).

Usevičiūtė, L., Baltrėnaitė-Gedienė, E. & Baltrėnas, P. Hydrophilicity enhancement of low-temperature lignocellulosic biochar modified by physical–chemical techniques. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 23, 1838–1854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-021-01255-y (2021).

Carneiro, M. A., Pintor, A. M. A., Boaventura, R. A. R. & Botelho, C. M. S. Arsenic and antimony desorption in water treatment processes: Scaling up challenges with emerging adsorbents. Sci. Total Environ. 929, 172602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172602 (2024).

ASTM. Standard practice for the prediction of contaminant adsorption on GAC in aqueous systems using rapid small-scale column tests (2021).

Maiti, P., Siddiqi, H., Kumari, U., Chatterjee, A. & Meikap, B. C. Adsorptive remediation of azo dye contaminated wastewater by ZnCl2 modified bio-adsorbent: Batch study and life cycle assessment. Powder Technol. 4, 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2022.118153 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Isotherm models for adsorption of heavy metals from water—A review. Chemosphere 307, 135545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135545 (2022).

Abdi, J. & Mazloom, G. Machine learning approaches for predicting arsenic adsorption from water using porous metal-organic frameworks. Sci. Rep. 12, 16458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20762-y (2022).

Park, S., Lee, J. H., Shin, T. J., Hur, H. G. & Kim, M. G. Adsorption and incorporation of arsenic to biogenic lepidocrocite formed in the presence of ferrous iron during denitrification by Paracoccus denitrificans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 9983–9991. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02101 (2018).

Huang, Y. et al. Highly-efficient and easy separation of hexahedral sodium dodecyl sulfonate/delta-FeOOH colloidal particles for enhanced removal of aqueous thallium and uranium ions: Synergistic effect and mechanism study. J. Hazard. Mater. 402, 123800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123800 (2021).

Mahdi, Z., El Hanandeh, A. & Yu, Q. J. Preparation, characterization and application of surface modified biochar from date seed for improved lead, copper, and nickel removal from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103379 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Zeolite supported Fe/Ni bimetallic nanoparticles for simultaneous removal of nitrate and phosphate: Synergistic effect and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 347, 669–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.088 (2018).

Pourhakkak, P., Taghizadeh, A., Taghizadeh, M., Ghaedi, M. & Haghdoust, S. Fundamentals of adsorption technology. Interface Sci. Technol. 33, 1–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818805-7.00001-1 (2021).

Wang, J. & Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 390, 122156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122156 (2020).

Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Da’ana, D. A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 393, 122383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122383 (2020).

Singh, P., Sarswat, A., Pittman, C. U. Jr., Mlsna, T. & Mohan, D. Sustainable low-concentration arsenite [As(III)] removal in single and multicomponent systems using hybrid iron oxide-biochar nanocomposite adsorbents-a mechanistic study. ACS Omega 5, 2575–2593. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02842 (2020).

Lin, L. et al. Arsenic removal in aqueous solution by a novel Fe-Mn modified biochar composite: Characterization and mechanism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 144, 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.06.063 (2017).

Nguyen, T. H. et al. Synthesis of iron-modified biochar derived from rice straw and its application to arsenic removal. J. Chem. 2019, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5295610 (2019).

Shaikh, W. A. et al. Enhanced aqueous phase arsenic removal by a biochar based iron nanocomposite. Environ. Technol. Innov. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.100936 (2020).

Kushwaha, R., Singh, R. S. & Mohan, D. Comparative study for sorption of arsenic on peanut shell biochar and modified peanut shell biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 375, 128831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.128831 (2023).

Yin, H., Kong, M., Gu, X. & Chen, H. Removal of arsenic from water by porous charred granulated attapulgite-supported hydrated iron oxide in bath and column modes. J. Clean. Prod. 166, 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.026 (2017).

Amen, R. et al. A critical review on arsenic removal from water using biochar-based sorbents: The significance of modification and redox reactions. Chem. Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.125195 (2020).

Fu, D. et al. Fabrication of alpha-FeOOH decorated graphene oxide-carbon nanotubes aerogel and its application in adsorption of arsenic species. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 505, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2017.05.091 (2017).

Xiong, H., Xu, S. & Zhu, S. Adsorption removal of arsenic from aqueous solutions and groundwater by isomeric FeOOH. Water Sci. Technol. 86, 1653–1667. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2022.303 (2022).

Weerasundara, L., Ok, Y. S. & Bundschuh, J. Selective removal of arsenic in water: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 268, 115668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115668 (2021).

Jain, N. & Maiti, A. Arsenite oxidation and arsenic adsorption strategy using developed material from laterite and ferromanganese slag: Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 15600–15612. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.3c01377 (2023).

Saldaña-Robles, A. et al. Arsenic removal from aqueous solutions and the impact of humic and fulvic acids. J. Clean. Prod. 159, 425–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.05.074 (2017).

Alchouron, J. et al. Household arsenic contaminated water treatment employing iron oxide/bamboo biochar composite: An approach to technology transfer. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 587, 767–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2020.11.036 (2021).

Zubair, Y. O., Fuchida, S. & Tokoro, C. Insight into the mechanism of arsenic(III/V) uptake on mesoporous zerovalent iron-magnetite nanocomposites: Adsorption and microscopic studies. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces 12, 49755–49767. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c14088 (2020).

Ali, S., Rizwan, M., Shakoor, M. B., Jilani, A. & Anjum, R. High sorption efficiency for As(III) and As(V) from aqueous solutions using novel almond shell biochar. Chemosphere 243, 125330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125330 (2020).

Niazi, N. K. et al. Arsenic removal by Japanese oak wood biochar in aqueous solutions and well water: Investigating arsenic fate using integrated spectroscopic and microscopic techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 1642–1651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.063 (2018).

Yuan, Z. et al. Characterization of Fe(5)(AsO(3))(3)Cl(2)(OH)(4).5H(2)O, a new ferric arsenite hydroxychloride precipitated from FeCl(3)-As(2)O(3)-HCl solutions relevant to arsenic immobilization. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 90, 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2019.12.009 (2020).

Hussain, A. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and applications of iron oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Health Sci. 17, 3–10 (2023).

Li, Y., Qi, X., Li, G. & Wang, H. Double-pathway arsenic removal and immobilization from high arsenic-bearing wastewater by using nature pyrite as in situ Fe and S donator. Chem. Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.128303 (2021).

Shahid, M. K., Phearom, S. & Choi, Y.-G. Evaluation of arsenate adsorption efficiency of mill-scale derived magnetite particles with column and plug flow reactors. J. Water Process Eng. 28, 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.02.015 (2019).

Rosales, E., Meijide, J., Pazos, M. & Sanroman, M. A. Challenges and recent advances in biochar as low-cost biosorbent: From batch assays to continuous-flow systems. Bioresour. Technol. 246, 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.084 (2017).

Brion-Roby, R., Gagnon, J., Deschênes, J.-S. & Chabot, B. Investigation of fixed bed adsorption column operation parameters using a chitosan material for treatment of arsenate contaminated water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6, 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2017.12.032 (2018).

Nguyen, T. H. et al. Arsenic adsorption by low-cost laterite column: Long-term experiments and dynamic column modeling. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 160, 868–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2022.03.010 (2022).

Zhu, X. et al. Life-cycle assessment of pyrolysis processes for sustainable production of biochar from agro-residues. Bioresour. Technol. 360, 127601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127601 (2022).

Zib, L., Byrne, D. M., Marston, L. T. & Chini, C. M. Operational carbon footprint of the U.S. Water and wastewater sector’s energy consumption. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128815 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Fe/TBC was analyzed in the Laboratory of Investigation and Characterization of Minerals and Materials (‘Laboratorios de Investigación y Caracterización de Minerales y Materiales’, LICAMM), and was synthesized in the Environmental Laboratory, Engineering Division, Universidad de Guanajuato. Thanks to Dr. Ignacio Rene Galindo Esquivel for his help on material characterization. All authors would like to thank all the professors and students who have helped the laboratory work. The first author acknowledges the support from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT No. 896367) and the China Scholarship Council (CSC No. 202210120001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by X.L., Y.L., R.M.A. The first draft of the manuscript was written by X.L., Y.L., R.M.A., A.H.S.M., D.O.R.A., R.Y.P.R., J.H.H.A., X.Z., D.M., M.J.P.A. and P.V.K. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, X., Miranda Avilés, R., Serafin Muñoz, A.H. et al. Efficient arsenic removal from water using iron-impregnated low-temperature biochar derived from henequen fibers: performance, mechanism, and LCA analysis. Sci Rep 14, 20769 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69769-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69769-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Advancements in water decontamination technologies: a special emphasis on adsorption techniques

Chemical Papers (2025)

-

Development of Agro-Based Engineered Biochars for Low Concentration Nitrate Adsorption: Modification Selection, Performance, Factors, Mechanism, and Reliability

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2025)

-

Remediation of arsenic-contaminated water: high effectiveness of modified biochars from legal amazon residues

Waste Disposal & Sustainable Energy (2025)