Abstract

The escalating prevalence of drug-resistant pathogens not only jeopardizes the effectiveness of existing treatments but also increases the complexity and severity of infectious diseases. Escherichia coli is one the most common pathogens across all healthcare-associated infections. Enzymatic treatment of bacterial biofilms, targeting extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), can be used for EPS degradation and consequent increase in susceptibility of pathogenic bacteria to antibiotics. Here, we characterized three recombinant cellulases from Thermothelomyces thermophilus: a cellobiohydrolase I (TthCel7A), an endoglucanase (TthCel7B), and a cellobiohydrolase II (TthCel6A) as tools for hydrolysis of E. coli and Gluconacetobacter hansenii biofilms. Using a design mixture approach, we optimized the composition of cellulases, enhancing their synergistic activity to degrade the biofilms and significantly reducing the enzymatic dosage. In line with the crystalline and ordered structure of bacterial cellulose, the mixture of exo-glucanases (0.5 TthCel7A:0.5 TthCel6A) is effective in the hydrolysis of G. hansenii biofilm. Meanwhile, a mixture of exo- and endo-glucanases is required for the eradication of E. coli 042 and clinical E. coli biofilms with significantly different proportions of the enzymes (0.56 TthCel7B:0.44 TthCel6A and 0.6 TthCel7A:0.4 TthCel7B, respectively). X-ray diffraction pattern and crystallinity index of E. coli cellulose are comparable to those of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) substrate. Our results illustrate the complexity of E. coli biofilms and show that successful hydrolysis is achieved by a specific combination of cellulases, with consistent recurrence of TthCel7B endoglucanase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cellulose is the most common biological macromolecule on Earth, primarily derived from terrestrial plants1. However, its presence extends beyond plants to microorganisms. Evolutionary studies suggest that the machinery responsible for bacterial cellulose synthesis and secretion (Bcs) was acquired from ancestral cyanobacteria through horizontal gene transfer2. Bcs systems can be classified into various types: I, II, III, Wss, and Ccs3. Each type produces a range of amorphous and crystalline cellulose forms, often featuring chemical modifications such as the addition of phosphoethanolamine (pEtN)4 and acetylation5,6.

The Bcs Type II system is characterized by the presence of the BcsE protein, which is triggered by the biofilm signal molecule, c-di-GMP, and BcsG, a phosphoethanolamine transferase7. Escherichia coli strains possess this machinery and synthesize cellulose, which combined with other extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), forms the bacterial biofilm8. E. coli cellulose enhances epithelial adhesion, influencing the invasion and biofilm formation in enteric and intestinal mucosa9. Chemical modifications of cellulose, such as pEtN, impact biofilm development. Specifically, the degree and pattern of pEtN substitutions of cellulose accelerates the fibrous arrangement of curli proteins10, which are another important component of the EPS in E. coli biofilms. The co-production of these polymers is relevant to the high adherence of E. coli biofilms on bladder cells under high shear conditions11.

Cellulose is a prevalent exopolysaccharide in both non-pathogenic and pathogenic bacterial biofilms, extending beyond E. coli12,13. However, further studies are necessary to comprehend the role of this polymer, particularly in pathogenic variants and strains. Recent studies on Mycobacterium tuberculosis highlight this notion, revealing the presence of cellulose in its biofilm, both in vitro14 and in vivo15. Challenges in such studies arise from the difficulties in detecting cellulose in in vivo environments, as cellulose synthesis is post-transcriptionally regulated, and the expression of Bcs genes does not reliably indicate cellulose presence9.

A pre-COVID-19 epidemiological study reveals that about 13.6% of all global deaths are linked to 33 species of pathogens, primarily driven by five bacterial strains in the following order of importance: Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa16. These pathogens were previously identified as strong biofilm formers, heightening their threat to human health due to the extensively reported tolerance and resistance to antibiotics conferred by the biofilm matrix17. Given a fact that E. coli is the second most lethal bacteria16, new treatments to combat E. coli infections are urgently needed.

Fungal and bacterial cellulases present promising candidates for the hydrolysis and treatment of cellulosic biofilms. This diversity is well-reflected in the CAZy database, which encompasses various glycoside hydrolase (GH) families. Some of these families are GH1, GH3, GH5, GH6, GH7, GH9, GH12, GH30, GH45, and GH4818. Cellulases exhibit four main activities: endo-β-1,4-glucanases (EC 3.2.1.4; GH5, GH9, GH12, GH45 and GH48), reducing end-acting cellobiohydrolases (EC 3.2.1.176; GH7), non-reducing end-acting cellobiohydrolases (EC 3.2.1.91; GH6), and β-glucosidases (EC 3.2.1.21; GH1, GH3 and GH30).

Several studies have reported the successful eradication and inhibition of the formation of various bacterial biofilms using cellulase cocktails from two main filamentous fungi, Trichoderma viride15,19,20,21,22 and Trichoderma reesei23,24,25,26. However, many of these studies employ elevated doses of cocktails primarily designed for plant biomass hydrolysis.

Here, we recombinantly produced a set of cellulases from Thermothelomyces thermophilus and applied them to cellulosic biofilms from Gluconacetobacter hansenii, E. coli 042, and a clinical E. coli strain CMA27. Using a design mixture experiment, we aimed to identify the most impactful cellulases for the degradation of these substrates, with the goal of reducing the enzymatic dosage required for the treatment of each microbial biofilm studied.

Results

Expression, purification and structural characteristics of TthCel7A, TthCel7B and TthCel6A

As revealed by previous genomic analysis27 the filamentous fungi T. thermophilus has a diversity of GHs encoded in its genome. It is predicted, excluding gene fragments, five and three members for the GH7 and GH6 families, respectively, distributed in almost all T. thermophilus genome, except for chromosomes 5 and 6 (Fig. 1a). We studied three different cellulases that encompass the most hallmarks of the fungal cellulase activities, employed for cellulose degradation. Cellobiohydrolases active on the reducing end of cellulose (TthCel7A/CBHI), an endoglucanase (TthCel7B/Egla), and a nonreducing end-acting cellobiohydrolase (TthCel6A/CBHII) were cloned into the pEXPYR vector28 and expressed on Aspergillus nidulans system. Remarkably, our target proteins cover all CBM-bearing GH6/GH7 cellulases (with carbohydrate-binding module) of T. thermophilus genome. Other predicted parameters showed a weight range between 46 to 54 kDa and the mostly acidic nature of these enzymes (Supplementary Table S1).

The CBM-bearing GH6 and GH7 cellulases from T. thermophilus. (a) Relative genomic position of the GH6 and GH7 genes, using the CAZy database and the Genome Data Viewer of NCBI. The cloned enzymes are named and placed under the corresponding chromosome with the accession numbers shown in black and bold letters. (b) Domain architecture of the cloned cellulases. SP corresponds to the predicted signal peptide excluded from the A. nidulans plasmid construction, while CBM refers to the carbohydrate binding module. Catalytic residues are highlighted in yellow, and loops involved in substrate recognition are marked in red, with names following previous nomenclatures. (c) Structure of T. thermophilus cellulases generated by ColabFold. TthCel7A (cyan), TthCel7B (gray), and TthCel6A (orange) are depicted in both cartoon and surface representations. Loops are colored in red, and catalytic residues are shown in yellow sticks. The substrate is docked, colored in green, and marked using previous crystallographic works on cellobiohydrolase I (PDB: 4C4C) and II (PDB: 1QK2) from T. reesei.

The recombinant cellulase production in A. nidulans expression system was successful (Supplementary Fig. S1), leading to pure enzymes with an average yield of 8.8 mg per liter of culture. All enzymes appeared as single bands with molecular masses higher when compared to the prediction: TthCel7A (66 kDa), TthCel7B (58 kDa) and TthCel6A (61 kDa). Since A. nidulans is capable of glycosylating its secreted proteins, an extra increase in the molecular masses is expected28.

The positions of the catalytic domain, CBM, and relevant loops are shown according to the Conserved Domain Database and the ColabFold structure model for the three cellulases (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. S2 & S3). TthCel7A and TthCel7B share a β-sandwich fold, formed by the alignment of two anti-parallel β-sheets positioned face-to-face29,30,31 (Fig. 1c) with their catalytic amino acid residues strictly conserved (Supplementary Fig. S2 & S3). Both structures incorporate short helical segments and functionally-relevant loop regions. The loops are arranged such that TthCel7A exhibits tunnel-like active site, whereas TthCel7B lacks long loops A4, B2, and B3 and, as a result, has a more open, active site cleft (Fig. 1b,c). Our previous crystallographic study of a native TthCel7A32 reveals a structure identical to that predicted here by the ColabFold AI approach. In contrast to GH7 enzymes, TthCel6A cellobiohydrolase has a TIM barrel fold (Fig. 1c), similar to that of GH6 cellobiohydrolases from T. reesei33 and Thermochaetoides thermophila34. Finally, the cellulases have a cellulose-binding module from CBM family 1 (CBM1) featuring a cysteine knot (Supplementary Fig. S4), localized at the C- or N-terminal of GH7 and GH6 enzymes, respectively (Fig. 1b).

Biochemical characterization

The studied fungal GH7 cellulases tend to have an optimal pH in the acidic range, while TthCel6A stands out with a neutral pH optimum (Fig. 2a). Lowering the pH can render glycosidic bonds more susceptible to enzymatic cleavage. Additionally, the acidic residues (e.g., aspartate and glutamate) in the active site of glucanases are more likely to be protonated, enhancing their ability to catalyze the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds in cellulose. All glucanases display a similar activity profile at high temperatures, with an optimum temperature around 60 °C (Fig. 2b). This is consistent with the natural habitat of T. thermophilus, which thrives under geothermal environments such as hot springs, where the temperatures can reach 50 to 60 °C. Furthermore, the observed thermostability is in line with the previous studies on native32 and recombinant enzymes from the same microorganism35,36.

Biochemical characterization of cellulases from T. thermophilus. The effects of pH and temperature on enzymatic activity are demonstrated in panels (a) and (b), respectively. (c) Substrate preference was determined using different types of cellulosic substrates. The standard enzymatic reaction consisted of 100 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 5, 0.5% (w/v) PASC substrate, and 0.1 μM of cellulase, incubated at 60 °C for 30 min. Variations were applied for each type of characterization as follows: For optimal pH, a citrate–phosphate-glycine buffer system ranging from pH 2 to 10 was used. For substrate preference, commercial celluloses such as Avicel PH-101 and low-viscosity CMC were used at 0.5% (w/v), along with a suspension of BC at 0.2% (w/v). All assays were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and the bars represent the standard deviation. (d) The binding isotherm adsorption of cellulases was evaluated on BC discs (approximately 0.6 mg in dry weight) with increasing concentrations of proteins incubated at 4 °C for 19 h. In (e), the identification of soluble products released by T. thermophilus cellulases is depicted. HPAEC-PAD analysis of the hydrolysis of BC discs was conducted using 1 μM of cellulase in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6, incubated at 37 °C for 20 h.

Cellulosic substrate preference analysis (Fig. 2c) indicates that, among all the studied cellulases, phosphoric acid-swollen cellulose (PASC) is the most favored substrate, except for TthCel7B, which shows higher efficiency in cleaving carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). Initial activity assays with the bacterial cellulose (BC) substrate reveal that cellobiohydrolases from the GH7 and GH6 families demonstrate moderate activity on this substrate. Avicel cellulose, known for its recalcitrance, ranks as the least preferred substrate for all the studied enzymes.

To gain insights into the binding interactions of the studied glucanases and cellulosic films, we performed binding isotherm experiments on BC (Fig. 2d). Using a Langmuir model, successful fitting of the experimental data with a linear equation was achieved (Supplementary Fig. S5). This first-order behavior can be explained by the low surface coverage of the enzymes within the BC disc structure, as demonstrated by previous works37. TthCel7A and TthCel7B exhibited high affinity for BC with apparent adsorption constants (KL app) of 177.07 and 181.51 μL/mg, respectively. In contrast, TthCel6A showed a low affinity with a KL app of 33.71 μL/mg (Fig. 2d). Studies using cleaved CBM from cellobiohydrolases I (Cel7A) and II (Cel6A) also showed a lower affinity of the latter for bacterial microcrystalline cellulose38. Our two GH7 enzymes share similar CBM structures, while TthCel6A possesses some extra amino acids that form a third cysteine bridge in its CBM (Supplementary Fig. S4). These structural features might be responsible for the differences in KL app between these two families of glucanases, however this hypothesis requires further investigation. Additionally, how CBMs impact the adsorption of cellulases on more complex and heterogeneous cellulosic substrates, such as those found in pathogenic bacteria biofilms, is an important research question to address in future studies.

A thorough investigation of BC substrate hydrolysis using the HPAEC system reveals distinct patterns in the release of cellobiose (C2), cellotriose (C3), and glucose (C1) (Fig. 2e). TthCel7A stands out by yielding a higher proportion of C2 while completely lacking C1 and exhibiting minimal C3 production. Meanwhile, TthCel6A produced an equivalent quantity of C2 as compared to TthCel7A, but with the simultaneous release of C1. On the other hand, TthCel7B generated the lowest amount of C2 and a modest fraction of C1. Notably, TthCel6A, when incubated for short periods at its optimal temperature (Fig. 2b), significantly reduces the production of C1 (Supplementary Fig. S6). To assess if TthCel6A is capable of degrading C2 into C1, we performed an enzymatic assay using 4-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) as the substrate at 37 °C and 60 °C and detected no glucosidase activity (Supplementary Fig. S6). An increase in C1 release indicates low processivity of the enzyme39, likely enhanced by the suboptimal and extended incubation of TthCel6A with the BC disc, as well as by the enzyme's low adsorption capacity to this substrate.

Enzyme mixture design experiments for hydrolysis of BC discs

The enzymatic interplay of mixing three types of cellulases, aiming to predict the hydrolytic response against two different cellulosic substrates (G. hansenii and E. coli biofilms) were investigated using the Simplex-Lattice design mixture model. We employed modified loading enzyme units (μM, with a constant reaction volume), allowing for normalization of enzyme weights across different cellulases by considering the total number of molecules.

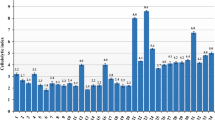

Following the hydrolysis of BC with a 100% loading of 6 μM of cellulases, we observed reducing sugars ranging from 0.202 to 1.577 mg/mL for specific enzyme combinations (Fig. 3a). The data exhibit some symmetry in terms of enzyme concentrations. For instance, when the concentrations of TthCel7A and TthCel6A are swapped (2 and 4 μM), the reducing sugar values are very similar (1.577 and 1.505 mg/mL), representing the highest product concentration. This suggests that TthCel7A and TthCel6A may have similar effects on reducing sugar production under these settings.

Design mixture experiments for the hydrolysis of BC discs. (a) The effect of the ternary cellulase mixture on the degradation of G. hansenii BC upon incubation at 37 °C for 20 h, plotted in terms of the released reducing sugars and its corresponding substrate conversion yield (in percentage). (b) Ternary contour plot of predicted reducing sugar concentration values from the {3,3} Simplex-Lattice design, with the predicted optimal mixture (TthCel7A: 0.493, TthCel6A: 0.507, and TthCel7B: 0.00, marked as a white star). (c) Production of reducing sugars and the corresponding substrate conversion yield over 20 h of incubation at 37 °C using the optimized mixture of glucanases (6 μM total enzyme loading: 2.96 μM TthCel7A and 3.04 μM TthCel6A). All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3) and bars represent the standard deviation.

To gain insights into our dataset in a more statistical and quantitative manner, we conducted a regression analysis using a special cubic model (Table 1). This model presents a high R-squared (0.931, p-value < 0.01) and adjusted R-squared (0.908, p-value < 0.01).

The individual factors Cel7A, Cel6A, and Cel7B each contribute moderately to the production of reducing sugars (Table 1). Meanwhile, the binary combination factors (Cel7ACel6A, Cel7ACel7B, and Cel6ACel7B) have higher impacts, demonstrating synergism in the enzymatic mixtures. Conversely, a negative coefficient was observed for the term Cel7ACel6ACel7B, suggesting an antagonistic effect. An alternative analysis of our data based on degree of synergism (DS) calculations shows comparable results to our Simplex-Lattice design (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Despite the equal mixture of the three components maintaining a high production of reducing sugars (1.403 ± 0.176 mg/mL), there was no further increase in their production. A plausible explanation for this phenomenon could be cellobiose inhibition and the jamming effect. The latter induces competition for free binding sites, leading to the crowding of cellulase molecules, and consequently a reduction in the enzymatic hydrolysis rate40.

All calculated coefficients of the factors were found to be statistically significant (p-value < 0.05). Then, the final Eq. (1) of reducing sugar production from BC in function of the amount of cellulases is as follows:

Taking equation above and varying the amounts of TthCel7A, TthCel7B, and TthCel6A in the reaction, we generated a ternary contour diagram to visualize the production of reducing sugars (Fig. 3b). The diagram reveals that the highest product yield (exceeding 1.5 mg/mL) is concentrated in the central region between the TthCel7A and TthCel6A axes and extending towards the lower end of the TthCel7B vertex.

To identify the optimal mixture of cellulases, we implemented a Python code to maximize the function response. The analysis revealed that an ideal composition consists of 49.3% TthCel7A and 50.7% TthCel6A, resulting in a predicted maximum reducing sugar yield of 1.66 mg/mL (Fig. 3b). To validate this outcome, we conducted an experimental trial using the optimized mixture (6 μM total cellulase loading: 2.96 μM TthCel7A and 3.04 μM TthCel6A), yielding a value of 1.58 mg/ml (approximately 26.3% of soluble products from BC) (Fig. 3c). This result deviates only by 4.82% from the modeled data. Similar exo/exo synergism was previously reported, for Cel7A and Cel6A enzymes from Humicola insolens41 and Hypocrea jecorina42. Initial models explain this synergism based on the endo-initiated hydrolysis mechanism of Cel6A enzymes41. However, more recent works claim that the targeting role of CBM is the main reason for exo/exo synergism42. Where, specifically, the Cel6A CBM targets amorphous regions more easily, while the Cel7A CBM has a high affinity for crystalline regions, complementing each other42,43. This also matches with the low and high binding affinity for BC discs of TthCel6A and TthCel7A, respectively (Fig. 2d).

Thus, our Simplex-Lattice design gave an output that is in line with previous studies described above, covering the extensively researched model of BC and cellulases. The following experiments were designed to challenge this optimization procedure to identify the best cellulase mixture for hydrolyzing more complex substrates.

Enzyme mixture design experiments for hydrolysis of biofilm of a pathogenic E. coli strain (EAEC 042)

Commensal and pathogenic E. coli produce biofilms containing cellulose44,45. Taking advantage of the recombinant cellulases, we used the enteroaggregative pathogenic E. coli 042 (EAEC) biofilm as a new target. The 100% enzyme loading was set to 1.5 μM, and a total of 40 experiments were performed (n = 4) for the 10 combinatorial conditions.

The raw data show that E. coli 042 is mildly susceptible to the enzymatic treatment, with a maximum eradication of 44.6% (Fig. 4a). Treatment with cellobiohydrolases TthCel7A and TthCel6A separately, produced almost no degradation of the biofilm, with overall degradation of 3.1 and 2.6%, respectively.

Design mixture experiments for the hydrolysis of a pathogenic E. coli 042 biofilm. (a) The effect of the ternary cellulase mixture on the degradation of E. coli 042 biofilm upon incubation at 37 °C for 20 h. (b) Ternary contour plot of predicted biofilm eradication values from a {3,3} Simplex-Lattice design, with the optimal response located at TthCel7B: 0.565 and TthCel6A: 0.435 (marked as a white star). (c) Dose–response experiment using a log2-dilution of the optimized cellulase mixture. The experiments were conducted using 24-h-old biofilms, where cellulases were applied after dilution in fresh TSB medium for 20 h at 37 °C. Biofilm biomass determination was achieved through CV staining. Each experiment was replicated three times (n = 3). (d) CLSM analysis of E. coli 042 biofilm under treatment with the optimized cellulase mixture (1 μM total enzyme loading: 0.565 μM TthCel7B and 0.435 μM TthCel6A:) and the least effective treatment, TthCel7A (1 μM). The protein matrix is visualized in red, while carbohydrates appear in blue following staining with SYPRO Ruby and Calcofluor White, respectively. GC corresponds to the growth control with no cellulase treatment (e) Analysis of the arithmetic mean intensity of representative micrographs (n = 4). (f) Biofilm viability test of E. coli 042 biofilms co-treated with the optimized cellulases mixture (1 μM, GH) and chloramphenicol (CHL) or tetracycline (TET) at 32 μg/mL (n = 4). Bars represent the standard deviation. P-value < 0.01; n.s. (non-significant difference) One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Next, we fitted our data to a full cubic model (R-squared: 0.93, p-value < 0.01; and adjusted R-squared: 0.905, p-value < 0.01) to obtain coefficients for each factor (Table 2). The coefficients of the linear factors Cel7A and Cel6A have minimal contributions to the model and are also not statistically significant, with p-values of 0.489 and 0.739, respectively.

However, there is a stronger synergism observed in the binary combinations; hence, the factor Cel7A Cel6A has a high coefficient of 158.3. This behavior is also evident in the other mixtures. All coefficients associated with the δ parameters of the model, despite their highly negative values, do not make a statistically relevant contribution to the fitting. The reduced Eq. (2), with statistically significant coefficients (p-value < 0.01), that describes the impact of cellulase proportions on the eradication of E. coli 042 biofilm is:

The ternary contour plot illustrates a region with higher eradication (> 36.1%) concentrated along the Cel7B and Cel6A axes (Fig. 4b). The specific combination of cellulases that maximizes the degradation of E. coli 042 biofilm, achieving up to 41.3% (predicted), consists of 56.5% TthCel7B and 43.5% TthCel6A. Overnight incubation of the optimized mixture diluted in fresh TSB medium and applied to a 24-h-old biofilm of E. coli 042 showed dose-dependent activity, with a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of approximately 0.63 μM (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. S8). When employing the same concentration used in the mixture design experiment (1.5 μM), a biofilm biomass growth of 54.1% (or a 45.9% level of eradication) was observed. This experimental value is 11.1% higher than the predicted value, which closely agrees with our adjusted R-squared for the model (0.905). Furthermore, at higher concentrations of the TthCel7B/TthCel6A synergistic mixture (6 μM), the biofilm did not exhibit any further degradation, retaining approximately 46.5% of its biomass (equivalent to 53.5% eradication).

To better comprehend the impact of cellulases on the structure of E. coli 042 biofilm, we conducted confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) experiments (Fig. 4d). Upon initial examination of the growth control, it became evident that the biofilm matrix is highly heterogeneous. In isolated regions, carbohydrates and proteins are co-localized, but the micrographs also revealed numerous structures consisting solely of a protein matrix.

In contrast, the application of 1 μM of the optimized treatment exhibited degradation of the carbohydrate polymers while leaving the protein matrix unaffected. Consequently, the protein matrix not only proved to be an abundant structure in E. coli 042 biofilm but also exhibited remarkable stability, showing minimal interaction with the carbohydrate component. This observation explains why our treatment achieved only a 53.5% level of hydrolysis, as the remaining portion is mainly attributed to the protein structure and/or possibly other EPS. The treatment with 1 μM TthCel7A exhibited no hydrolysis, as confirmed by the CV-staining test, which showed only a 3.1% eradication rate. Due to the high heterogeneity of this biofilm, visual analysis presented difficulties. Therefore, we recorded the mean intensity of fluorescence for each channel (Fig. 4e). In the Calcofluor White channel, we found a significant difference (p < 0.01) between the growth control (37.1 a.u.) and the optimized cellulase mixture (23.1 a.u.), but no significant difference for the TthCel7A treatment (32 a.u.). Although the intensities on the Calcofluor White and SYPRO Ruby channels in the growth control were not statistically significant, a noticeable trend towards a more proteinaceous biofilm was observed. All these characteristics are reflected in the absence of synergism of the cellulase mixture with antibiotics (chloramphenicol and tetracycline) in reducing biofilm viability (Fig. 4f).

Enzyme mixture design experiments for hydrolysis of the biofilm of a clinical E. coli strain (E. coli CMA27)

The previous approach was utilized in this section to degrade established biofilms of a non-multi-drug resistant clinical E. coli strain isolated from urine samples of a patient with a urinary tract infection in the Microbiology Laboratory of the State University of Ponta Grossa (PR, Brazil) (Supplementary Fig. S9, Table S2) denominated as E. coli CMA27. The phylogeny of the E. coli CMA27 strain is shown in the Supplementary Figure S10.

The initial data demonstrates the effectiveness of the enzyme combinations in eradicating E. coli CMA27 biofilms (Fig. 5a). A substantial degradation was observed, ranging from approximately 76.1% to 94.1%. Higher concentrations of TthCel7B (1.5 μM) were correlated with higher biofilm eradication. The presence of TthCel7A and TthCel6A also contributed to biofilm eradication, but their individual effects are less clear, as the percentages vary across different combinations.

Design mixture experiments for the hydrolysis of a clinical E. coli CMA27 biofilm. (a) The effect of the ternary cellulase mixture on the degradation of E. coli CMA27 biofilm upon incubation at 37 °C for 20 h. (b) Ternary contour plot of predicted biofilm eradication values from a {3,3} Simplex-Lattice design, with the predicted optimal mixture (TthCel7A: 0.596 and TthCel7B: 0.404, marked as a white star). (c) Dose–response experiment using a log2-dilution of the optimized cellulase mixture. All experiments were performed on 24-h-old biofilms, applying T. thermophilus cellulases diluted in fresh TSB medium for 20 h at 37 °C. The test employed for the determination of biofilm biomass was CV staining. Experiments were performed in quadruplicates (n = 4), and the bars represent the standard deviation. (d) Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) analysis of E. coli CMA27 biofilm. Untreated biofilms were used as controls (GC). The effect of the optimized mixture of cellulases (1 μM total enzyme loading: 0.596 μM TthCel7A and 0.404 μM TthCel7B) and TthCel6A (1 μM) on the biofilm architecture is illustrated. The protein matrix is shown in red, and carbohydrates in blue after staining with SYPRO Ruby and Calcofluor White, respectively. (e) Cellulase co-treatment effect with different antibiotics. Tetracycline, gentamicin, and chloramphenicol antibiotics were used at concentrations between 0.125 and 32 μg/mL and in cotreatment with 1 μM of optimized cellulase mixture. All measurements were performed with the resazurin test in triplicates (n = 3), and bars represent the standard deviation.

The non-linear regression, using a full cubic model, presents good R-squared values (0.975, p-value < 0.01) and adjusted R-squared (0.967, p-value < 0.01) (Table 3). The linear coefficients show the higher effect of the cellulases when applied individually, with Cel7B (92.9) being the highest, followed by Cel7A (84.2) and Cel6A (76.1). In all binary mixtures, a synergistic effect is observed, with all coefficients being positive. The δ parameters are statistically significant (p < 0.01) and contribute to the fitting of the model. Additionally, we found a strong negative interaction of the three cellulases (− 124.4 coefficient) with this type of substrate.

The following is the final Eq. (3) derived from the model above:

Using the described approach, we created a ternary contour plot based on the Eq. 3. Visually, a clear shift in the proportion of cellulases leading to significant biofilm degradation was observed (Fig. 5b). There is a distinct region with a high percentage of degradation situated close to the midpoint between the Cel7B and Cel7A axes, and at the lower end of the Cel6A vertex, where degradation exceeds 91.7%. The cellulase proportions that maximize the output of the model (which predicted 94.3% eradication) were found to be 59.6% for TthCel7A and 40.4% for TthCel7B.

In a dose–response experiment using this newly optimized mixture, it was found that the EC50 is approximately 0.086 μM (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. S11) for E. coli CMA27 biofilm eradication. It is worth emphasizing that increasing the concentration beyond 2 μM did not result in complete degradation of the biofilm biomass. At treatment concentrations ranging from 1 to 2 μM, which is close to the concentration used in the mixture design experiment (1.5 μM), residual biofilm biomass of approximately 16% was quantified. In other words, there was 84% degradation, which is 10.6% lower than the predicted eradication value.

The CLSM 3D volume images reveal that the 24-h-old E. coli CMA27 biofilm, without any treatment, exhibits a robust and heterogeneous structure of carbohydrate and protein matrix (Fig. 5d). This colocalization is evident in the merged micrograph channels, with the biofilm thickness measuring approximately 235 μm at the highest point of the z-stack measurements.

When treated with the optimized cellulase mixture, there was a significant reduction in the carbohydrate signal. Surprisingly, the protein matrix signal was also diminished, possibly due to a strong interaction between these two types of biofilm matrix components. Even when applying the least effective cellulase, TthCel6A, the biofilm still degraded, reducing the thickness to 138 μm while maintaining the heterogeneity observed in the control experiment. This result is consistent with the previously conducted CV staining, which reported a 76.1% eradication rate.

To further demonstrate the effectiveness of the optimized cellulase mixture in degrading the carbohydrate component of the E. coli CMA27 biofilm, we conducted experiments using three different antibiotics. The minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) values for tetracycline, gentamicin, and chloramphenicol were 4, 4, and 8 μg/mL, respectively. In all cases, even at very low antibiotic concentrations, greater efficacy in reducing biofilm viability was observed when co-incubated with the cellulases (Fig. 5e).

E. coli strains possess the capability to produce cellulose modified by phosphoethanolamine, a distinctive feature of E. coli cellulose that plays a crucial role in the biofilm structure. This modification holds the potential to enhance virulence traits in opportunistic strains, including cohesion, adhesion, and defense against predators and antimicrobials46. The phosphoethanolamine modification exhibits the potential to induce cellulose to function as an adhesive, thereby promoting the aggregation of E. coli cells and facilitating robust adhesion to bladder epithelial cells11,46. Moreover, the altered cellulose interacts with the antigenic curli, concealing them and thereby aiding the bacteria in evading immunological detection. Conversely, the majority of non-pathogenic K12 strains of E. coli fail to synthesize cellulose due to the incomplete functionality of the gene cluster4,5. Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S amplicon sequence reveals that the E. coli CMA27 lineage clustered with other clinically significant lineages, including those associated with urinary infections, and was more distantly related to lineages isolated from the environment and humans without clinical history (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Biofilm characterization

The switch to the optimal mixture of T. thermophilus cellulases against the described cellulosic structures demonstrates a common use of endoglucanase in the eradication tests of both E. coli CMA27 and 042 strains. This indicates the prevalence of an amorphous cellulosic structure in biofilms. As previously mentioned, the E. coli cellulose secretion system (Bcs type II) produces pEtN cellulose, which is naturally amorphous4.

To experimentally demonstrate this, we isolated the cellulose fraction from the studied biofilms. A preliminary Congo red stain indicated the presence of carbohydrates both before and after acidic purification, with a relatively higher concentration in the E. coli CMA27 biofilm (Fig. 6a). Sulfuric acid hydrolysis followed by the DNS assay of both biofilms confirmed higher reducing sugar content in E. coli CMA27 (31.6 mg/g of lyophilized biofilm) compared to E. coli 042 (18.8 mg/g) (Fig. 6b). The dried, purified cellulose was subjected to X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis, which also included dried and ground bacterial cellulose (BC) and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) (Fig. 6c). The cellulose from G. hansenii displayed an XRD pattern with two major peaks at approximately 22.47° and 14.41° 2θ angles, corresponding to the previously reported cellulose profile47 (Fig. 6c). In contrast, both E. coli biofilms exhibited broad peaks spanning angles around 18° and 24°, indicative of an amorphous structure. Surprisingly, both patterns closely resembled the CMC diffractogram.

Characterization of cellulose from bacterial biofilms. (a) Congo red staining of E. coli CMA27 and 042, before (i, iii) and after (ii, iv) cellulose extraction; and G. hansenii production of cellulose biofilm before (i) and after (ii) the treatment with 0.1 M NaOH (bottom panel). (b) Determination of total reducing sugar content by acid hydrolysis of lyophilized biofilms. (c) XDR pattern obtained from the cellulose purified from G. hansenii, E. coli CMA27 and 042, and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). (d) Bcs operon arrangement of E. coli 042 (accession: PRJEA40647) and G. hansenii ATCC 23769 (PRJNA43711), with distinctive genes highlighted in blue. Alignment of the 5′ flanking region (highlighted in red) of E. coli 042 bcsQ gene with E. coli strain 55989 (PRJNA33413) and E. coli K-12 (PRJNA16351).

We conducted a deconvolution analysis of the data to separate the peaks in the X-ray diffractograms and calculate the crystallinity index (CrI). This approach allowed us to determine the CrI for each isolated cellulose sample (Fig. 6c). It confirmed that the CrI for G. hansenii cellulose was higher at 72% compared to E. coli biofilms and CMC. A slight difference in CrI was observed between the cellulose from the clinical E. coli CMA27 biofilm (53.27%), the pathogenic model E. coli 042 biofilm (49.86%), and the CMC substrate (46.12%), with the latter being the more amorphous substrate. This difference could be explained by the presence of more chemical substitutions in the cellulose structure (carboxymethyl and pEtN groups), which hinder its packing into an ordered cellulose polymer.

The physical differences reported here between bacterial cellulose biofilms rely on specific genes that modify the nascent cellulose chains. To confirm the presence of these genes and describe them, we analyzed and illustrated the bacterial cellulose (Bcs) operon of both studied models using the reported genomic data of E. coli 04248 and G. hansenii49 (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. S12). In E. coli 042, the bcsG gene is found, whose product is fundamental for the addition of pEtN to the cellulose chain3,5. The existence of more chemical substitutions in the cellulose structure hinders its packing into an ordered polymer, resulting in low CrI (Fig. 6c). In contrast, one of the three Bcs operons (denominated by previous studies as operon I50) present in G. hansenii possesses the bcsD gene, which is crucial for the crystalline arrangement of cellulose fibrils3,5.

BcsQ is another relevant gene found in E. coli 042, which is not related to the structure of cellulose but to its production and robustness. It has been previously reported that a premature termination codon mutation in bcsQ results in E. coli strains lacking the capacity for cellulose synthesis, such as E. coli K-1251. In contrast, the absence of this mutation leads to the formation of robust cellulosic biofilms, such as those produced by E. coli strain 55,98951 and the E. coli 042 studied here, which possesses an intact bcsQ gene (Fig. 6d). This highlights a significant diversity of E. coli Bcs operons and their impact on biofilm formation, as well as the lack of a genetic marker to predict robustness, which would improve the treatment of cellulosic biofilms.

Discussion

Simplex-Lattice design experiments using cellulases have been reported for optimizing biomass hydrolysis52,53,54,55. In the present study, individual recombinant glucanases were used under this model to optimize the hydrolysis of cellulosic biofilms. The results of optimizing the hydrolysis of BC, which is strictly a non-decorated and highly crystalline bacterial cellulose, reveal a classical exo/exo synergism41,42. The hydrolysis of E. coli biofilms switches to exo/endo synergistic action with recurrent presence of TthCel7B endoglucanase.

However, there are differences between the E. coli CMA27 and 042 patterns of degradation, showing the diversity of the biofilm response. E. coli CMA27 is significantly more susceptible to the optimized enzymatic treatment, with a sevenfold lower EC50 as compared to E. coli 042. The cellulase and antimicrobial co-treatment reveals the difficulty in treating a strain with multiple antibiotic resistances such as E. coli 042, which has genes encoding resistance to chloramphenicol, tetracycline, streptomycin, spectinomycin and sulfonamide48.

The treatment of E. coli biofilms with cellulases has been previously reported, with variations in growth conditions and enzymatic application. For instance, the enteropathogenic E. coli O157: H7 biofilm, grown in BHI medium for 24 h, was exposed to 20 mg/mL of a commercial cellulase from Trichoderma viride for 1 h in a tenfold diluted medium, resulting in a degradation of 29.3%19. In contrast to these findings, we achieved a 50% degradation of established biofilms from E. coli CMA27 and E. coli 042, using 3.2 μg/mL and 18 μg/mL of cellulases (expressed previously in μM units), respectively. It is important to highlight that we conducted a 20-h enzyme incubation under the same culture conditions, using TSB as the dilution medium. This approach helped us avoid suboptimal growth conditions, which are more likely to render biofilms more vulnerable to treatments.

Another study showed that treating a uropathogenic E. coli strain 536 with an unknown commercial cellulase (13.8 U/mL) resulted in a reduction of the aggregative index by up to 75%. In this case, a 3-h incubation was performed on an aggregative model, which is a variant of the biofilm model, using the culture medium RPMI 164056. Isolated cellulose from a mutant E. coli MG1655 was degraded with a T. reesei cocktail (5 mg/mL) during a 16-h incubation to confirm the polysaccharide nature of the biofilm, according to another research group23.

Cellulases have been employed to degrade different cellulosic biofilms, such as those found in Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin, resulting in a degradation rate of 70.6% when using 1.024 mg/mL of an unidentified cellulase57. Studies conducted on M. tuberculosis biofilms revealed the efficacy of treating infected human lung tissue with a 5 mg/mL T. viride cellulase cocktail. Additionally, nebulization with 20 U (approx. 2 mg) of the same cocktail in a mouse model demonstrated a reduction in cellulose signals in a CLSM experiment, consequently reducing the lung area involved in the pathology15. Both studies address the in vivo application of cellulases in a murine model by using vein-injected cellulases encapsulated in nanoparticles57 or via nebulization15. These are potential routes for the medical treatment of biofilm-associated diseases.

The identical cocktail and concentration (5 mg/mL) were also employed to treat Mycobacterium intracellulare biofilms associated with catheter implants in a mouse model20. A comprehensive study involving 12 different biofilms treated with various enzymes indicated that Enterobacter cancerogenus was the only biofilm eradicated, at approximately 50%, following the application of about 1 mg/mL of the T. viride cellulase cocktail21.

Additional examples are provided for various biofilms, including B. cereus biofilm58, mono- and dual-species biofilms of P. aeruginosa59, S. aureus biofilms in a wound model60,61, Salmonella variants22,62, and Enterococcus faecalis24 biofilms.

From all the cited works, it is evident that high concentrations (ranging from 1 to 30 mg/mL) of various cocktails of fungal cellulases from different strains, such as T. viride (sometimes commercialized as Cellulase R-10)15,19,20,21,22, T. reesei (sometimes commercialized as Celluclast)23,24,25,26, and A. niger59,60,61, have been used for biofilm eradication. These mixtures are primarily formulated for the hydrolysis of plant cellulose and typically consist of cellobiohydrolases, endoglucanases, and glucosidases in varying proportions. In fact, an analysis of the Celluclast cocktail reveals a predominant composition of hemicellulases (40%), followed by cellulases (30%)55.

The implementation of a Simplex-Lattice design mixture model has provided a robust method for optimizing the proportion of cellulases capable of hydrolyzing different bacterial cellulose biofilms. There are differing responses of both E. coli samples to the same set of enzymes. The endoglucanase TthCel7B is found in different percentage proportions, ranging from approximately 40.4% to 56.5% of the binary mixture. Although TthCel7B is not the main factor in the hydrolysis of all E. coli biofilms, it remains consistently present in the optimized mixtures. Since E. coli cellulose is highly amorphous and possesses structural properties close to that of CMC (Fig. 6c), we propose the latter synthetic substrate as a model that mimics the cellulosic biofilm. Indeed, TthCel7B exhibits high CMCase activity (Fig. 2c), making CMC a good starting point for screening new bacterial biofilm-active enzymes. Further studies on new glucanases with potential for biofilm degradation could be found in the same Bcs operon, where genes like bcsZ (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. S12) produce a GH8 endoglucanase highly active on CMC63. Searching for enzymes with tolerance to other chemical modifications such as acetylation would broaden specific treatment options against bacterial targets, including those associated with Pseudomonas and Clostridium species.

Materials and methods

Microbial strains and culture conditions

A. nidulans A773 (pyrG89; wA3; pyroA4) was purchased from the Fungal Genetic Stock Center (FGSC, Manhattan, KS, USA). G. hansenii ATCC 23769, Escherichia coli CMA27, and 042 were obtained from collaborators. A. nidulans A773 was cultivated on Minimum medium agar composed of Clutterbuck salt solution (6 g/L NaNO3, 0.52 g/L KCl, 0.52 g/L MgSO4, and 1.52 g/L KH2PO4) and trace elements (22 mg/L ZnSO4, 11 mg/L H3BO3, 7.9 mg/L MnCl2. 4H2O, 5 mg/L FeSO4.7H2O, 1.6 mg/L CoCl2. 6H2O, 1.6 mg/L CuSO4. 5H2O, 1.1 mg/L Na2MoO4 0.4H2O, and 50 mg/L EDTA salt), supplemented with 1% (w/v) glucose and 0.01 mg/mL pyridoxine. E. coli biofilm was cultivated in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) at 37 °C under static conditions. G. hansenii ATCC 23,769 was grown in a medium consisting of 2.5% (w/v) mannitol, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, and 0.3% (w/v) peptone (pH 6) at 30 °C for 15 days without agitation.

Molecular identification of bacterial strain by 16S ribosomal gene sequencing

E. coli CMA27 was cultivated in Luria–Bertani Broth (LB: 10 g/L tryptone; 10 g/L NaCl; 5 g/L yeast extract, pH 7.0 ± 0.2) at 37 °C with agitation at 100 rpm for 24 h. Subsequently, 200 µL of the culture was collected and subjected to molecular identification by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene. Total DNA was extracted using the ReliaPrep™ Blood gDNA Miniprep System Kit from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). The primers fD1 (5′-CCGAATTCGTCGACAACAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and rD1 (5′-CCCGGGATCCAAGCTTAAGGAGGTGATCCAGCC-3′) were used for the amplification. The PCR reaction consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 55 °C for 45 s and extension at 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension cycle at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR kit (n° 28,104) from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). After purification of the PCR products, band integrity was verified through electrophoresis, and the obtained material was sent for sequencing to Ludwig Biotec (Alvorada, Brazil). The sequences were analyzed using resources from the Ribosomal Database Project site. The strain was identified as Escherichia coli, with accession number PP126331—NCBI, named Escherichia coli CMA27.

Phylogenetic analysis

16S rRNA sequences from the species E. coli and the genera Klebsiella and Salmonella of clinical and environmental origin, containing more than 1000 bp, were selected. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method, with the percentage of replicate trees in which associated taxa were clustered in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates). Evolutionary distances were calculated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are expressed in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. This analysis involved 8 nucleotide sequences. All ambiguous positions were removed for each pair of sequences using the pairwise deletion option. Evolutionary analyses were performed in MEGA X.

Susceptibility to antimicrobials

The antimicrobial susceptibility test was carried out using the disk diffusion method. E. coli CMA27 was cultured in Miller Hinton Broth (MH: 2 g/L meat extract; 17.5 g/L acid-hydrolyzed casein; 1.5 g/L starch, pH 7.3 ± 0.2), at 37 °C for 24 h. The growth was standardized to an optical density (OD) between 0.08 and 0.1 at 625 nm. Using a sterile swab, the culture was evenly inoculated onto the surface of Petri dishes containing Miller Hinton Agar (MH + 17 g/L agar). Subsequently, discs of the following antimicrobials were placed on the inoculated Petri dishes: Amoxicillin (20 µg) + Clavulanate (10 µg) (AMC 30, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Ampicillin (AMP 10: 10 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Aztreonam (ATM 30: 30 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Ceftazidime (CAZ 30: 30 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Cefepime (CPM 30: 30 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Ceftriaxone (CRO 30: 30 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Gentamicin (GEN 30: 30 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Levofloxacin (LVX 5: 5 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); Meropenem (MER 30: 30 µg, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil); and Piperacycline (100 µg) + Tazobactam (10 µg) (PPT 110, Laborclin, Pinhais, Brazil). The Petri dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the results were evaluated by the presence or absence of growth inhibition halos. The diameter of the inhibition zones was measured, and E. coli CMA27 was classified as resistant (R) or sensitive (S) to antimicrobials according to the expected halo values for Enterobacteriaceae provided by the manufacturer.

Cloning of cellulases

All cloned enzymes were kindly provided by the research group of Prof. Fernando Segato (University of Sao Paulo, Lorena School of Engineering). To clone the enzymes, genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from fresh mycelia of T. thermophilus M77 using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The genes were amplified from gDNA via the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Q5® High-Fidelity 2 × Master Mix (New England Biolabs) with specific oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S3) containing assembly regions (highlighted in bold). An endoglucanase, TthCel7B (Accession number: XP_003663441.1), a cellobiohydrolase, TthCel7A (Accession number: XP_003660789), and a cellobiohydrolase form the GH6 family, TthCel6A (Accession number: XP_003661032) were cloned using a high-expression-secretion vector, pEXPYR, in an A. nidulans host strain, following a previously described protocol28.

Cellulase production and purification

Glycerinated spores from successfully transformed A. nidulans were inoculated onto minimum medium agar plates supplemented with 0.01 mg/mL pyridoxine and 1% glucose, then incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. For recombinant protein production, the resulting mycelia was inoculated into a Minimum medium broth supplemented with 3% maltose, 1% glucose, and 0.01 mg/mL pyridoxine, and incubated for 2 days under static conditions at 30 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was recovered through filtration using a qualitative membrane (Miracloth, Millipore), followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min to eliminate all cellular debris and mycelia. This solution was then concentrated and buffer-exchanged (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8) using tangential flow filtration with a 5 kDa cut-off HollowFiber cartridge (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Next, an ion exchange chromatography in a gravity flow was performed using a DEAE-Sephadex resin (Sigma) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8. The proteins of interest were eluted with a NaCl gradient (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 M). All three proteins underwent further purification employing size exclusion chromatography in a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, and 150 mM NaCl buffer. Fractions corresponding to the proteins were pooled and concentrated. The purity of the proteins was evaluated by 12% SDS-PAGE, and they were quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) at 280 nm (TthCel7A, theoretical mass = 54 kDa, ɛ = 91.8 M−1 cm−1; TthCel6A, theoretical mass = 48.62 kDa, ɛ = 90.93 M−1 cm−1; TthCel7B, theoretical mass = 46.63 kDa, ɛ = 83.07 M−1 cm−1, as predicted by ProtParam). Finally, the enzymes were sterilized through syringe membrane filtration (0.22 μm).

Bacterial cellulose production

BC was produced by G. hansenii ATCC 23769 in a mannitol-rich medium, as previously described47. The culture was grown in 200 mL of medium within a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask. After 15 days, the cellulose discs were harvested, and the attached bacteria were removed by incubating the discs in 100 mM NaOH at 80 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, the discs were thoroughly rinsed with water until a neutral pH was achieved. Smaller discs, each with a diameter of 6 mm (~ 0.6 mg of dry weight), were manually cut using a paper puncher. Finally, the BC discs were sterilized via autoclaving. Additionally, a BC suspension was prepared at a concentration of 0.36% (w/v) using a homogenizer.

Substrate preference, temperature and pH response

The standard enzymatic reaction was conducted in a 100 mM buffer with 0.1 μM of cellulase and a suitable substrate at the optimal temperature, then incubated for 30 min. Reducing sugars were quantified using the DNS method64, with one enzymatic unit (U) defined as the amount of enzyme that produces 1 μmol of reducing sugar per minute. Optimal pH was determined by employing a citrate–phosphate–glycine buffer system, spanning from pH 2 to 10, while utilizing 0.5% (w/v) PASC as the substrate at 60 °C. Optimal temperature was tested in a sodium acetate buffer at pH 5 with 0.5% (w/v) PASC as the substrate, over a temperature range of 20 to 80 °C.

The screening of different cellulose substrates involved a mixture of 0.1 μM of cellulase, a 100 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 5, and 0.5% (w/v) of commercial substrates (Avicel PH-101, CMC low viscosity, or PASC) or 0.2% (w/v) BC suspension, followed by incubation at 60 °C for 30 min. Additionally, the synthetic substrate 4-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) was tested to characterize TthCel6A as described in the Supplementary Materials.

HPAEC-PAD analysis

The degradation of BC discs and the detection of the types of soluble sugars released were assessed using High-Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography coupled with Pulsed Amperometric Detection (HPAEC-PAD). The reaction involved a mixture of 1 μM of cellulase, a 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6, and a BC disc in a final volume of 350 μL. This mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. Subsequently, the reaction was stopped by incubating it at 95 °C for 5 min, and the soluble fraction was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane before analysis. The products were analyzed with a CarboPac PA1 (2 × 250 mm) analytical column (Dionex Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in a Dionex ICS 5000 system (Dionex Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Both column and detector compartments were maintained at 30 °C. One microliter of the sample was injected, and solutions of 0.1 M NaOH (A) and 0.1 M NaOH with 1 M NaOAc (B) were the eluents. The flow was set to 0.3 mL min−1, and the gradient was as follows: from 0 to 10% B in 10 min, 10 to 30% B in 15 min, 30 to 100% B in 5 min, 100% B for 8 min, 100 to 0% B in 1 min, followed by column re-equilibration for 15 min.

Binding isotherm of cellulases

Binding isotherms were determined by incubating 50 μL of cellulase solution at different concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 mg/mL) with BC discs (~ 0.6 mg in dry weight) in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6 and 4 °C for 19 h. The protein concentration was quantified by measuring absorption at 280 nm using a NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA), based on the theoretical mass and extinction coefficient (see Supplementary Table S1). The following reduced Langmuir isotherm Eq. (4) was used to determine the adsorption constants37:

Here, Ca represents the μg of protein adsorbed per mg of BC in dry weight, KL app is the apparent adsorption constant in μL/mg, and Cf is the concentration of free protein in μg/μL.

Structural modelling of cellulases

The structures of T. thermophilus cellulases were computationally modeled using ColabFold65. To incorporate substrates into our predicted model, we utilized the crystallographic structure of cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei, TrCel7A (PDB: 4C4C), as a template. Additionally, we used the structure of cellobiohydrolase II from the same organism, TrCel6A (PDB: 1QK2), and performed structural alignments with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5.8. Schrödinger, LLC). The identification of loops was achieved through a protein alignment with representative cellulase sequences and by following established nomenclatures29,32.

Optimization of the mixture of cellulases for the hydrolysis of BC and E. coli biofilms

We simultaneously tested three cellulases with CBM as a cocktail to study the synergistic response to different cellulosic substrates. To achieve this, we used a mixture design experiment called {q, m} Simplex-Lattice design, where each component or variable is a proportion that needs to sum to 1 or 100%. Three (q) components (TthCel7A, TthCel6A, TthCel7B) and four (m + 1) equally spaced levels (0, 0.333, 0.667, and 1) for this especific {3, 3} Simplex-Lattice design were employed. The resulting number of experimental points is defined by \({{\left( {q + m - 1} \right)!} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {q + m - 1} \right)!} {\left( {\left( {m!\left( {q - 1} \right)!} \right) } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {\left( {m!\left( {q - 1} \right)!} \right) } \right)}}\), giving a total of 10 runs (Table 4).

As we are maintaining the same volume in all reactions, the use of concentration units (μM) can be added arithmetically to achieve a 100% mixture. Furthermore, the total enzyme dosage was selected based on the biochemical characterization of the enzymes studied in this research. To ensure a strong signal, relatively high concentrations of cellulases were used to compensate for the suboptimal temperature and pH conditions. Thus, the optimization of G. hansenii cellulose discs degradation involved maintaining a total dose of 6 μM of the cellulase mixture while varying the combination ratios, as outlined in Table 4. The reaction comprised a specific enzymatic mixture, one BC disc (~ 0.6 mg in dry weight), a 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6, in a final volume of 100 μL (6 g/L final concentration of BC). After a 20-h incubation at 37 °C, as suggested for biofilm models66, 50 μL of the supernatant containing the released reducing sugars were mixed with 50 μL of DNS and incubated at 100 °C for 5 min. The quantification was carried out by measuring the absorbance at 540 nm and comparing it to a glucose standard curve. The released sugars were used to calculate the substrate conversion yield (relative percentage of hydrolysate concentration to initial substrate concentration, 6 g/L) and the degree of synergism, as described in previous studies67,68. This experiment was conducted in triplicates (n = 3).

The same approach was employed to enhance the degradation of E. coli biofilms, with a fixed 100% fraction of the cellulase mixture at 1.5 μM. The degradation of 24-h-old biofilms was quantified using CV staining. A total of forty experimental runs were conducted (n = 4).

The independent variables, TthCel7A (X1), TthCel6A (X2), and TthCel7B (X3) and the response Y1 (concentration of reducing sugars or biofilm biomass eradication) was submeted to a regression analysis using the package software MATLAB 9.12.0 (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) and a special cubic model shown in Eq. (5).

Or a full cubic model, represented in Eq. (6).

Biofilm eradication and inhibition assay

A robust clinical biofilm-forming E. coli strain (E. coli CMA27) and the pathogenic E. coli 042 were utilized in the subsequent experiments. For the eradication assay, an overnight bacterial culture was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.05 with fresh TSB medium. Subsequently, 100 μL of this suspension was added to a 96-well plate and allowed to grow under static conditions for 24 h at 37 °C. The biofilm was then washed twice with 150 μL of 0.9% NaCl, and 100 μL of a two-fold serial dilution of the optimized cellulase mixture in TSB broth was applied. After 20 h of incubation at 37 °C, the remaining biomass of the biofilm was washed again and quantified using crystal violet (CV) staining. Briefly, 105 μL of a 0.1% (w/v) CV solution was added and agitated for 30 min at room temperature. Following this, the biofilm was rinsed with ultrapure water and dried before destaining with 110 μL of 70% (v/v) ethanol for 30 min with gentle shaking66. The absorbance at 595 nm (A595) was recorded and the percentage of biofilm eradication was calculated using the Eq. (7):

where SCA595 and GCA595 correspond to the absorbance measurements of the control without inoculation and the biofilm control without enzyme treatment, respectively.

Resazurin viability assay

The percentage of metabolically active bacteria was determined by adding 20 µL of a 0.15 mg/mL resazurin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) solution to 100 µL of the resuspended cells. This mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h in a 96-well black plate in static conditions and the fluorescence was measured at the excitation/emission wavelengths of 550/590 nm, respectively, in an Infinite 200 M PRO microplate reader (Tecan, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland). The percentage of metabolically active cells was calculated using the Eq. (8):

where SC550/590 and GC550/590 correspond to the fluorescence measurements of the control without inoculation and the biofilm control without enzyme treatment, respectively. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

MBEC test and synergism with antibiotics

At first, the Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC) was determined for multiple antibiotics for E. coli CMA27strains. Twenty-four hours-old biofilms were produced. Then, serial dilutions (from 34 to 0.125 μg/mL) or specific concentrations of chloramphenicol, tetracycline and gentamicin diluted in TSB medium were applied into the washed biofilms and incubated for another 24 h. After that, the supernatant was discarded, and the remaining biofilms were resuspended in 100 μL of 0.9% NaCl and the cells were dispersed using an ultrasonic bath for 10 min. Then, the metabolic active bacteria were quantified using the resazurin stain, in order to determine de MBEC. After that, the same proceeding was employed for the analysis of the synergistic effect of the cellulase mix (1 μM) and the antibiotics. The cellulase treatment was applied simultaneously with each antibiotic at a concentration below the before determined MBEC, and the metabolically active bacteria were measured through the resazurin fluorescence All treatments were performed in triplicates (n = 3). In the case of E. coli 042 treatment, tetracycline and chloramphenicol at 32 μg/mL were tested alone and in conjunction with 1 μM of the cellulase mix, to finally apply the resazurin test. All treatments were performed in quadruplicate (n = 4).

Biofilm cellulose extraction, Congo red staining and total reducing sugar determination

Biofilms were cultured employing 150 mm Petri dishes to increase adherent surfaces, and for that, we used a total of 500 mL of liquid culture medium. After 24 h, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min. Meanwhile, the adherent biofilms were solubilized using a 1% (v/v) Triton-X100 solution and then centrifuged under the same conditions. Both resulting pellets were combined and washed with a 0.9% NaCl solution. A solution containing 30 mL of 80% (v/v) acetic acid and 3 mL of concentrated nitric acid was added to the pellet. The mixture was then incubated at 100 °C for 30 min in a water bath. The hydrolyzed products were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min. Finally, the insoluble cellulose fraction pellet was retrieved, washed with ultrapure water, and dried for further studies. Biofilm as is and after purification were stained with Congo red at a final concentration of 80 μg/mL and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Unspecific binding was avoided by three sequential washes with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl. A red staining was visually inspected. Furthermore, lyophilized biofilms were subjected to acid hydrolysis for the quantification of reducing sugars using the DNS test, as detailed in the Supplementary Materials.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Twenty-four hours-old biofilms from E. coli CMA27 and 48 h-old biofilms from E. coli 042, were grown in a 24-well plate with a final volume of 0.5 mL per well, as described above. The treatment involved applying either 1 μM of the optimized cellulase mixture or 1 μM of the least effective treatment to each biofilm. Then, the planktonic remaining bacteria were discarded, and the biofilms were rinsed twice with 0.9% NaCl. Five hundred microliters of White Calcofluor solution (10 μg/mL) were applied to the biofilms which were then incubated in the dark for 15 min. Then, the excess stain was washed twice with 0.9% NaCl solution. After that, 500 μL of FilmTracer™ SYPRO® Ruby biofilm matrix stain was applied to the biofilm and incubated at room temperature protected from light for 20 min. A final wash with 0.9% NaCl solution was performed. These samples were analyzed using a fluorescence confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 780, Oberkochen, Germany) with an EC Plan-Neofluar 10X objective, and images were acquired at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels and a scanning area of 850.2 μm × 850.2 μm (voxel size: 1.66 μm × 1.66 μm × 8.10 μm). The Calcofluor White was excited at 405 nm and the fluorescence emission was detected at 447 nm. SYPRO® Ruby was excited at 450 nm, and its emission was captured at 610 nm. At first, each biofilm (control and enzyme-treated) was imaged at six random locations within the total field of view. The processing of representative images with a minimum total Z-stack of 137.7 μm (18 slices) was performed to avoid any region with poor biofilm growth or detachment during the washing process. Furthermore, from the associated statistical values of the fluorescence histogram, the arithmetic mean of fluorescence was obtained at the middle plane of the Z-stack for all the CLSM images (n = 4, for each condition) and analyzed graphically. All the image analysis and 3D reconstruction were performed using ZEISS ZEN 3.8 software (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Powder X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were acquired from dried and grinded cellulose obtained from G. hansenii, E. coli CMA27, and E. coli 042. The measurements were performed using a Miniflex 600 (Rigaku, Japan) X-ray diffractometer operating at 40 kV and 15 mA, with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at ambient temperature. Detection covered the 2θ range from 5 to 50°, with a step interval of 0.05° and an exposure time of 15 s per step. Individual diffraction peaks were extracted by a curve-fitting process from the experimental diffraction scans to calculate the crystallinity indices. Peak fitting program (PeakFit; www.systat.com) was used to assume Gaussian functions for each peak and a broad background distribution with maximum at around 21.5° was assigned to the amorphous scattering contribution, as described by Park et al.69.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using the Origin version 2020 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) statistical package, and quantitative results are presented as means and standard errors. For data meeting the assumptions of parametric tests (Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests), comparisons among multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For dose–response analysis, EC50 was obtained using a non-linear curve fit of cellulase mixture (Log2 [cellulase mixture]) versus biofilm biomass. The reduced Langmuir equation fitting was performed using a user-defined model, as specified in Eq. 4.

Data availability

The 16S rRNA gene sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the GenBank—NCBI under the accession number PP126331. The strain was identified as Escherichia coli and designated as Escherichia coli CMA27. The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bar-On, Y. M., Phillips, R. & Milo, R. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 6506–6511 (2018).

Little, A. et al. Revised phylogeny of the cellulose synthase gene superfamily: insights into cell wall evolution. Plant Physiol. 177, 1124–1141 (2018).

Abidi, W., Torres-Sánchez, L., Siroy, A. & Krasteva, P. V. Weaving of bacterial cellulose by the Bcs secretion systems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 46, 1–35 (2022).

Thongsomboon, W. et al. Phosphoethanolamine cellulose: A naturally produced chemically modified cellulose. Science 1979(359), 334–338 (2018).

Römling, U. & Galperin, M. Y. Bacterial cellulose biosynthesis: Diversity of operons, subunits, products, and functions. Trends Microbiol. 23, 545–557 (2015).

Scott, W., Lowrance, B., Anderson, A. C. & Weadge, J. T. Identification of the Clostridial cellulose synthase and characterization of the cognate glycosyl hydrolase, CcsZ. PLoS One 15, e0242686 (2020).

Abidi, W., Zouhir, S., Caleechurn, M., Roche, S. & Krasteva, P. V. Architecture and regulation of an enterobacterial cellulose secretion system. Sci. Adv. 7, 8049–8076 (2021).

Sharma, G. et al. Escherichia coli biofilm: Development and therapeutic strategies. J. Appl. Microbiol. 121, 309–319 (2016).

Ellermann, M. & Sartor, R. B. Intestinal bacterial biofilms modulate mucosal immune responses. J. Immunol. Sci. 2, 13–18 (2018).

Tyrikos-Ergas, T. et al. Synthetic phosphoethanolamine-modified oligosaccharides reveal the importance of glycan length and substitution in biofilm-inspired assemblies. Nat. Commun. 13, 3954 (2022).

Hollenbeck, E. C. et al. Phosphoethanolamine cellulose enhances curli-mediated adhesion of uropathogenic Escherichia coli to bladder epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 10106–10111 (2018).

Flemming, H.-C. et al. The biofilm matrix: multitasking in a shared space. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 70–86 (2023).

Moradali, M. F. & Rehm, B. H. A. Bacterial biopolymers: from pathogenesis to advanced materials. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 195–210 (2020).

Trivedi, A., Mavi, P. S., Bhatt, D. & Kumar, A. Thiol reductive stress induces cellulose-anchored biofilm formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 7, 11392 (2016).

Chakraborty, P., Bajeli, S., Kaushal, D., Radotra, B. D. & Kumar, A. Biofilm formation in the lung contributes to virulence and drug tolerance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 12, 1606 (2021).

Ikuta, K. S. et al. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 400, 2221–2248 (2022).

Ciofu, O., Moser, C., Jensen, P. Ø. & Høiby, N. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 621–635 (2022).

Singh, A., Bajar, S., Devi, A. & Pant, D. An overview on the recent developments in fungal cellulase production and their industrial applications. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 14, 100652 (2021).

Lim, E. S., Koo, O. K., Kim, M.-J. & Kim, J.-S. Bio-enzymes for inhibition and elimination of Escherichia coli O157:H7 biofilm and their synergistic effect with sodium hypochlorite. Sci. Rep. 9, 9920 (2019).

Yamamoto, K., Tsujimura, Y. & Ato, M. Catheter-associated Mycobacterium intracellulare biofilm infection in C3HeB/FeJ mice. Sci. Rep. 13, 17148 (2023).

Kim, M.-J., Lim, E. S. & Kim, J.-S. Enzymatic inactivation of pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria in biofilms in combination with chlorine. J. Food Prot. 82, 605–614 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Removal of Salmonella biofilm formed under meat processing environment by surfactant in combination with bio-enzyme. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 66, 298–304 (2016).

Gualdi, L. et al. Cellulose modulates biofilm formation by counteracting curli-mediated colonization of solid surfaces in Escherichia coli. Microbiology (NY) 154, 2017–2024 (2008).

Velázquez-Moreno, S. et al. Use of a cellulase from Trichoderma reesei as an adjuvant for enterococcus faecalis biofilm disruption in combination with antibiotics as an alternative treatment in secondary endodontic infection. Pharmaceutics 15, 1010 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Impact of different enzymes on biofilm formation and mussel settlement. Sci. Rep. 12, 4685 (2022).

Leroy, C., Delbarre, C., Ghillebaert, F., Compere, C. & Combes, D. Effects of commercial enzymes on the adhesion of a marine biofilm-forming bacterium. Biofouling 24, 11–22 (2008).

Berka, R. M. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the thermophilic biomass-degrading fungi Myceliophthora thermophila and Thielavia terrestris. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 922–927 (2011).

Segato, F. et al. High-yield secretion of multiple client proteins in Aspergillus. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 51, 100–106 (2012).

Payne, C. M. et al. Fungal cellulases. Chem. Rev. 115, 1308–1448 (2015).

Kleywegt, G. J. et al. The crystal structure of the catalytic core domain of endoglucanase I from Trichoderma reesei at 3.6 Å resolution, and a comparison with related enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 272, 383–397 (1997).

Bodenheimer, A. M. & Meilleur, F. Crystal structures of wild-type Trichoderma reesei Cel7A catalytic domain in open and closed states. FEBS Lett. 590, 4429–4438 (2016).

Kadowaki, M. A. S., Higasi, P., de Godoy, M. O., Prade, R. A. & Polikarpov, I. Biochemical and structural insights into a thermostable cellobiohydrolase from Myceliophthora thermophila. FEBS J. 285, 559–579 (2018).

Rouvinen, J., Bergfors, T., Teeri, T., Knowles, J. K. & Jones, T. A. Three-Dimensional Structure of Cellobiohydrolase II from Trichoderma reesei. Science 1979(249), 380–386 (1990).

Thompson, A. J. et al. Structure of the catalytic core module of the Chaetomium thermophilum family GH6 cellobiohydrolase Cel6A. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 875–882 (2012).

Yang, J. et al. Modulation of the catalytic activity and thermostability of a thermostable GH7 endoglucanase by engineering the key loop B3. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 248, 125945 (2023).

Dadwal, A., Sharma, S. & Satyanarayana, T. Recombinant cellobiohydrolase of Myceliophthora thermophila: Characterization and applicability in cellulose saccharification. AMB Express 11, 148 (2021).

Califano, D. et al. Multienzyme cellulose films as sustainable and self-degradable hydrogen peroxide-producing material. Biomacromolecules 21, 5315–5322 (2020).

Arola, S. & Linder, M. B. Binding of cellulose binding modules reveal differences between cellulose substrates. Sci. Rep. 6, 35358 (2016).

Uchiyama, T. et al. Convergent evolution of processivity in bacterial and fungal cellulases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 19896–19903 (2020).

Bommarius, A. S. et al. Cellulase kinetics as a function of cellulose pretreatment. Metab. Eng. 10, 370–381 (2008).

Boisset, C., Fraschini, C., Schülein, M., Henrissat, B. & Chanzy, H. Imaging the enzymatic digestion of bacterial cellulose ribbons reveals the endo character of the cellobiohydrolase Cel6A from Humicola insolens and its mode of synergy with cellobiohydrolase Cel7A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 1444–1452 (2000).

Badino, S. F. et al. Exo-exo synergy between Cel6A and Cel7A from Hypocrea jecorina : Role of carbohydrate binding module and the endo-lytic character of the enzymes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 114, 1639–1647 (2017).

Ganner, T. et al. Dissecting and reconstructing synergism. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 43215–43222 (2012).

Zogaj, X., Nimtz, M., Rohde, M., Bokranz, W. & Römling, U. The multicellular morphotypes of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli produce cellulose as the second component of the extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1452–1463 (2001).

Bokranz, W., Wang, X., Tschäpe, H. & Römling, U. Expression of cellulose and curli fimbriae by Escherichia coli isolated from the gastrointestinal tract. J. Med. Microbiol. 54, 1171–1182 (2005).

Jeffries, J., Fuller, G. G. & Cegelski, L. Unraveling Escherichia coli ’s cloak: Identification of phosphoethanolamine cellulose, its functions, and applications. Microbiol. Insights 12, 117863611986523 (2019).

Costa, A. F. S., Almeida, F. C. G., Vinhas, G. M. & Sarubbo, L. A. Production of bacterial cellulose by Gluconacetobacter hansenii using corn steep liquor as nutrient sources. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2027 (2017).

Chaudhuri, R. R. et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative metabolic profiling of the prototypical enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain 042. PLoS One 5, e8801 (2010).

Pfeffer, S., Mehta, K. & Brown, R. M. Complete genome sequence of a Gluconacetobacter hansenii ATCC 23769 isolate, AY201, producer of bacterial cellulose and important model organism for the study of cellulose biosynthesis. Genome Announc. 4, e00808-e816 (2016).

Florea, M., Reeve, B., Abbott, J., Freemont, P. S. & Ellis, T. Genome sequence and plasmid transformation of the model high-yield bacterial cellulose producer Gluconacetobacter hansenii ATCC 53582. Sci. Rep. 6, 23635 (2016).

Serra, D. O., Richter, A. M. & Hengge, R. Cellulose as an architectural element in spatially structured Escherichia coli biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 195, 5540–5554 (2013).

Laothanachareon, T., Bunterngsook, B., Suwannarangsee, S., Eurwilaichitr, L. & Champreda, V. Synergistic action of recombinant accessory hemicellulolytic and pectinolytic enzymes to Trichoderma reesei cellulase on rice straw degradation. Bioresour. Technol. 198, 682–690 (2015).

Inoue, H., Decker, S. R., Taylor, L. E., Yano, S. & Sawayama, S. Identification and characterization of core cellulolytic enzymes from Talaromyces cellulolyticus (formerly Acremonium cellulolyticus) critical for hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7, 151 (2014).

Bunterngsook, B. et al. Optimization of a minimal synergistic enzyme system for hydrolysis of raw cassava pulp. RSC Adv. 7, 48444–48453 (2017).

Suwannarangsee, S. et al. Optimisation of synergistic biomass-degrading enzyme systems for efficient rice straw hydrolysis using an experimental mixture design. Bioresour. Technol. 119, 252–261 (2012).

Rowe, M. C., Withers, H. L. & Swift, S. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli forms biofilm aggregates under iron restriction that disperse upon the supply of iron. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 307, 102–109 (2010).

Zhang, Z. et al. Synergistic antibacterial effects of ultrasound combined nanoparticles encapsulated with cellulase and levofloxacin on Bacillus Calmette-Guérin biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1108064 (2023).