Abstract

Brunei, similar to other nations, encounters difficulties in effectively managing solid waste, with 70% of the waste ending up in landfills, 2% through composting, and the remainder being disposed of through conventional methods. The current landfill site is anticipated to reach its maximum capacity in 2025. Energy recovery from waste is crucial for Brunei since it can improve waste management, mitigate environmental consequences, produce economic advantages, bolster energy security, and promote a circular economy. This study aims to identify the potential for energy recovery through landfill gas generated from solid waste disposal in Brunei Darussalam. The study finds that Brunei Darussalam can produce 129 thousand tonnes of CO2e/year landfill gas. Utilising gas to generate electricity of 367 GWh could save 1.6 million USD annually. In addition, it also identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the existing solid waste management in Brunei Darussalam. Furthermore, it formulates a waste management policy in Brunei Darussalam by identifying relevant stakeholders to overcome the weakness. Lastly, the framework for waste management is designed to consider short-, intermediate- and long-term goals and targets, with actions to be taken by respective stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Classified as a high-income country according to the Human Development Index, 20031, Brunei Darussalam's Solid Waste Management (SWM) can be regarded as a low-income country. Problems associated with solid waste management in a low-income country are more complex than those associated with a high-income country2. Moreover, rapid urbanization and the increasing population complicate a lack of infrastructure and financial resources. This causes a rapid increase in solid waste generation. Cities accommodate 2% of the world's surface, consume 75% of global resources, and generate 70% of global waste, approximately 2 billion tonnes of solid waste annually3,4,5. At this rapid rate, by 2025, it is estimated that this figure will increase to 2.2 billion tonnes6. Solid waste management services consume 3–15% of municipal budgets7 and thus continue to be a concern. Solid waste management is undoubtedly the most important service a municipal authority in a country can offer. The high population growth rate and increase in economic activities in urban areas of low-income countries and the lack of training in modern solid waste management practices complicate efforts to improve solid waste management services8,9. The amount of waste material we produce and how we manage it has profound implications for the environment's quality and future generations' prospects10.

The per capita GDP of Brunei is $ 37,152 (https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/BRN/brunei/gdp-per-capita), which is considered as high-income countries and therefore, the waste characteristics are similar to other high-income countries like Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain. Brunei Darussalam, rich in oil and gas resources, relies heavily on fossil fuels for electricity generation. The modern sanitary landfill at Sungai Paku has arrangements for a gas ventilation system, though the gas has not been collected. Therefore, this study aims to identify the potential for energy recovery by identifying the amount of landfill gas utilised to generate electricity. The potential of greenhouse gases (GHG) from municipal solid waste (MSW) is estimated using the IPCC method11. Properly accounting for GHG emissions at the local scale and identifying actions for GHG reduction is still an open challenge in many contexts.

On a regional scale, waste is one of Southeast Asia's more visible environmental problems due to its urban growth since the 1980s12. Urbanisation is a growing concern for waste disposal in Brunei Darussalam, particularly recently. Therefore, it is crucial to formulate a waste management policy to overcome any challenges arising from increasing waste. More research-based knowledge is needed to underpin waste management policies13. However, for designing and implementing a waste management policy, it is important to understand the behavioural drivers of the stakeholders, particularly when the policy is focused on preventing food waste generation and redirecting these resources to recyclable outputs14. Integrated research studies are essential to implementing current and future policies to overcome the barriers to waste management. Solid waste management can strengthen municipal management and is a prerequisite for other municipal services such as health and recreation.

A World Bank study indicates that urban areas in Asian cities spend US $25 million annually on solid waste management6. This study is significant as Brunei Darussalam faces the challenge of an increased population, with its only sanitary landfill expected to be full in the next 5–7 years. Thus, the solid waste management system in Brunei Darussalam needs to be reviewed and improved by integrating public, private, and policy-based approaches. Forming a waste management policy has attracted keen attention among various stakeholders due to increasing concerns about food security and environmental impacts, such as resource depletion and GHG emissions15, which occur during food production, storage, transportation, and waste management16. For solid waste management to operate progressively and efficiently, a policy must be well set to address any issues relating to waste and its management. The policy must then uphold a strong commitment to protecting the environment from waste impacts, which helps people oblige.

The primary objective of this study is to determine the potential for landfill methane recovery and its utilisation for electricity generation, as well as to develop a waste management policy framework that addresses the deficiencies of the current waste management system.

Existing solid waste management in Brunei Darussalam

Brunei Darussalam has a per capita solid waste generation rate of 1.4 kg per day, the third highest among the ASEAN countries17,18,19,20,21. From the total waste produced, 70% goes directly to Brunei's six landfills, a meagre 2% is used for compost, and the rest is disposed of in conventional ways20. All wastes are transported to the Sungai Paku landfill site, which averages 500 tonnes daily, 60% from Brunei-Muara and Temburong and 40% from Tutong and Belait. In some areas in Temburong, waste is still disposed of in the form of open dumping. Regarding construction waste (concrete and boulders), the Sungai Paku Landfill site receives 100 tonnes per day, which are further crushed into smaller aggregates (used for road pavement) through a grinding mill at the landfill site. The landfill site has two leachate treatment ponds for treating leachate.

A waste truck can support three daily trips from the transfer station to the Sungai Paku landfill site. The frequency of waste collection is every day, from midnight to dawn. Occasionally, 10 trucks are utilised for the collection. Most of the time, private companies follow the instructions of the Municipal Department. There are two government bodies: the Department of Environment, Park and Recreational (JASTRe), responsible for collecting waste in Brunei Darussalam, and the Municipal Department, responsible for collecting municipal waste in the municipal area18.

The composition of waste in Brunei consists of almost 36% of food waste. A significant portion of waste, 55% (Paper, plastic, metal, glass, wood, and textiles), is recyclable waste20. Oily waste accounts for a large part of the waste generated from industrial sectors. After the extraction of oil composition for recycling purposes, the remaining residues are disposed of in landfill sites designed for industrial waste or combusted by the incinerator. Private waste management companies own and operate These waste treatment facilities. Cement stabilisation and solidification technology have been applied to treat hazardous waste and chemical substances in landfill sites.

Since the government does not have national standards and guidelines for landfill sites and incinerators, the private sector voluntarily uses International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards. The private sector periodically sends environmental performance reports to JASTRe for information sharing and monitoring.

Currently, there are only acts that regulate waste disposal and management. Even when new enforcement and information about waste-related rules exist, it is only indicated as a memo from a higher authority. No "black and white" paper indicates it as a rule, act, policy, or otherwise. In this case, the initiative is understood to be short-term. JASTRe is the statutory governmental agency responsible for waste and its effects on the environment. Although the department has devised and delivered its acts, the higher authority has yet to be gazetted or officiated. This department co-exists under the Ministry of Development.

Methods

In this study, the emission of CH4 is calculated using Eq. (1) based on IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories11 and based on existing solid waste collection of 70%.

where MSW is the amount of MSW disposed of by landfill (t/a); MCF is the CH4 correction factor (Fraction), 0.6 for the present study; DOC is the degradable organic carbon [fraction (tC/t MSW)] is calculated using Eq. (2); A indicates the total amount of paper (18%) and textiles (2%) as the fraction of MSW; B indicates the total amount of putrescible non-organic (Yard waste, 6%) as the fraction of MSW; C indicates the amount of food waste (36%) as the fraction of MSW; D indicates the amount of wood (1%) or straw as the fraction of MSW; DOCF fraction DOC dissimilated, IPCC Guidelines provide a default value of 0.77; F is the fraction by volume of CH4 in landfill gas, the CH4 fraction F can vary between 0.4 and 0.6 while for our present study, considered as 0.5; O.X. is the oxidation factor, IPCC suggests 0.1. Based on the existing practice of composting for 10 t/day, i.e., 2% of SWM20 is used for composting. We calculate the GHG emission– CO2, N2O and CH4 resulting from composting using the following Eqs. (3)–(5)22:

where CCH4% is the percent of C converting to CH4 (%).

In the composting system, the percent of carbon converted to CO2 is 55%, in line with 50–60% of the input carbon proposed by Boldrin et al.23. The total carbon degraded percentage was assumed to be 66–84% based on hemicelluloses and fibre degradation rates during the composting period23. We considered carbon degradation at 75% in Eq. (3) for CH4 emissions. The percent of carbon converted to CH4 is considered 2%, consistent with the range of 0.8–2.5%24.

where Cinput is the total carbon content in raw waste (kg), CCO2% is the percent of C converting to CO2 (%).

We have considered the total carbon content in raw waste as 0.46 kg/kg, and the percent of C converting to CO2 is 57%25.

Ninput is the total nitrogen content in raw waste (kg), and NN2O% is the percent of N converting to N2O (%).

We have considered the total carbon content in raw waste as 4.36 × 10−3 kg/kg of raw waste, and the percent of N converting to CO2 is 2.6%25.

Stakeholders, roles, and responsibilities in waste management policy

Reynaud et al. defined a stakeholder "as any entity with a declared or conceivable interest or stake in a policy concern"26. Many policies fail due to a lack of awareness among the stakeholders and poor enforcement by the regulators27. According to Bingham et al.28, effective and widely supported legislation requires adequate stakeholders' consultation. Gaining support from stakeholders for waste management policy is critical when emphasizing recycling, reduction, reuse, and recovery (4Rs)29. In the waste management system in Brunei Darussalam, the stakeholders are defined as government institutions, educational institutions, the private sector, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Results and discussions

Strength

There are several strengths in managing waste in Brunei Darussalam (Table 1). For example, a statutory right or position imposed on a department or agency indicates that such a department is the main authoritative body for handling solid waste and is responsible for its management. As for the country, JASTRe is assigned as the authoritative governmental agency that controls and enforces the execution of waste management. An engineered landfill in Sungai Paku is a positive step towards waste management in Brunei Darussalam. Its onsite recovery of demolition waste (concrete and boulders) is a promising endeavour for recovering materials from paved aggregates used for constructing roads. Besides, several green campaigns have been made to take a step to change the attitude and mindset towards environmental conservation in the country. For example, the Society for Community Outreach and Training (SCOT) organized the sixth Green Exchange Project held at Kg Batu Marang in 2014. Another effort the Brunei government made to encourage people to practice recycling was enforcing a no-plastic bag weekend. The "No Plastic Bag Weekend" was started on March 26, 2011. This green initiative aims to reach a recycling rate of 20% by 202030, and the "No Plastic Bag" campaign will be introduced for all days by January 1, 2019.

Weakness

Apart from the strength of waste management in Brunei Darussalam, there are also weaknesses in waste management (Table 1); for example, no policy acts only to regulate waste. Brunei Darussalam has yet to establish a national policy specifying waste management matters in the country. The Waste Acts impose an acceptable liability of BND $500 to offenders who dispose of waste irresponsibly, but they were lenient with a $200 fine rate. Despite enforcement, the Act's implementation is often relaxed due to inadequate human resources. There are no initiatives to segregate the waste at household levels. There are not enough recycling facilities in the country. Although private companies' initiatives exist to help lessen the composition of solid waste, they have yet to receive support from a national initiative to offer recycling facilities. The existing waste management shows that even the waste from the government sector mostly goes straight to the landfill and does not go through the recycling phase.

The private sector receives many recyclable resources, which are free or sometimes purchased from citizens and business fields. Their target covers household commodities such as cans, PET, and paper, including end-of-life vehicles, e-waste, and construction waste. After the collection and dismantling process, valuable parts or resources are picked up for recycling; however, all of these resources are finally exported to other countries due to the lack of material/thermal recycling facilities in Brunei Darussalam. Waste and scrap export data (Table 2) clearly shows that the recycling industry in Brunei Darussalam depends heavily on other countries for the downstream recycling process. Import data also indicates that there is only a small demand for secondary resources in the country.

The main source of energy in Brunei Darussalam is oil and gas. The lack of waste recovery initiative by producing energy from tapped methane gas at the landfill site is still absent. Currently, landfills are the best option for waste disposal in the country. Therefore, other options like incineration, composting, and energy recovery have not been considered. The dependency on this method has resulted in the exhaustion of land capacity and the life span of the location. It is getting difficult to look for a new landfill, with many parts of Brunei Darussalam protected by a reserve forest. Only several percent of the country's land is provided for development, resulting in competition. The activities related to waste management are circulated to only those affected by them. The understanding of the act is not circulated to the public, which causes the public to have a limited knowledge of the already implemented acts.

Risk assessment

Risk assessment is essential for solid waste management and energy recovery research. These investigations identify, analyse, and prioritise risks to guarantee solution efficacy and sustainability. Conducting a risk assessment for landfill gas (LFG) recovery entails identifying, analyzing, evaluating, and mitigating hazards linked to the extraction and utilisation of gas produced from the decomposition of organic waste in landfills. Hazard identification is the initial stage of risk assessment. It involves identifying potential dangers, such as high methane levels that can cause explosions and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Exposure to components of landfill gas, like hydrogen sulphide, can also harm human health. Other risks to consider include operational issues like equipment failure, leaks, and blockages in the gas collection system and environmental risks like the potential for groundwater contamination. The subsequent stage entails assessing the probability and possible consequences of the identified risks and the probability of their occurrence and collecting data on gas production rates, equipment dependability, incident reports, and regulatory obligations. The third phase is risk evaluation, which compares the analysed risks with pre-established risk criteria to assess their acceptability. This is done by creating a risk matrix, setting appropriate risk limits, and identifying issues that must be addressed.

Devise and execute plans to reduce unacceptable risks by installing and maintaining gas collection and control systems (such as flares and gas-to-energy systems), implementing ongoing monitoring of gas composition, flow rates, and system integrity, regularly maintaining gas collection infrastructure to prevent leaks and ensure optimal functioning, establishing safety protocols for managing and addressing gas leaks and emergencies, and providing personnel with training on safety procedures, equipment operation.

Proposed waste management system

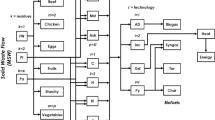

Since a significant portion of waste comprises organic composition in Brunei Darussalam, recyclable waste segregation at the point of generation should be given top priority (Fig. 1) in the waste management policy. Hence, containers (green and grey) should be provided to segregate household waste. Green containers are used for organic or kitchen waste, while grey containers are used for recyclable waste such as plastic, paper, and cans. However, plastic litter is a major issue that creates nuisances in the Brunei River. As a result, two-stage segregation is required at the transfer station to ensure only non-recyclable waste, excluding organic waste, goes into the landfill. The proposed waste management system also highlights the importance of exporting recyclable materials, as the country lacks a recycling industry. Internationally, the recycling industry has more than 2 million informal waste collection companies. On the local scale, an inefficient waste management system can contribute to soil air pollution and public health impacts such as respiratory issues and disease. Thus, improving solid waste management by exporting recyclable materials is becoming an urgent priority.

Besides, it is recommended that energy be tapped from landfill gas (CH4) and utilised for energy production due to its great potential33,34,35. Waste to Energy (WtE) has a role to play in the circular economy, contributing to sustainable waste management policies that enable countries to set specific targets in the context of resources and energy efficiency36,37,38 and mitigate environmental issues39,40,41 to promote low-carbon cities42. Solid waste management policy is important for biogas development due to the high potential of biogas generation from the organic waste portion of the MSW landfill43.

M.S.W. is the 4th largest contributor to global emissions by sharing 550 Tg (1Tg = 1012 g) global methane emissions per annum44. Proper estimation of GHG emissions at the local scale and identifying actions for GHG reduction are still an open challenge in many contexts45. Figure 2 indicates the CH4 emission potential of urban solid waste in different districts of Brunei Darussalam. Brunei-Mura has the highest potential for CH4 emission from landfill, which is 89,594 tonnes of CO2e/year due to its large population, followed by Tutong with 21,423 tonnes CO2e/year, Kuala Belait with 15,132 tonnes CO2e/year, and very small population with highly dense forest cover, Temburong has 3227 tonnes CO2e/year. In total, 129,377 tonnes (0.13 million tonnes) of CO2e/year can be emitted as landfill gases compared to other countries, as shown in Fig. 3. Crude oil and natural gas served as the primary energy sources of Brunei Darussalam. In 2015, the majority (84%) of the total primary energy was supplied by natural gas, while oil accounted for the remaining 16%. Brunei intends to establish a new solar power plant with a capacity of 30 MW, aiming to increase the country's solar energy production to 200 MW by 2025. The goal is for solar power to constitute a minimum of 30% of the total power generation mix by 2035. Brunei's electricity generation data was reported at 4269.85 GWh in December 201646. Suppose landfill gas can be utilised to generate electricity. In that case, it can generate electricity of 367 GWh (367,431,833.05 KWh), resulting in savings of 3 million USD, as shown in Table 3. This would assist the government in diversifying the energy mix through WtE efforts, which contribute to 8.6% of total electricity generated, and promote alternative energy sources for power generation.

However, the gas collection efficiencies range between 13 and 86% for different landfills, with an average of 50% (Denmark), Swedish (58%), U.K. (76%), and U.S. (63%)48,49. This study considers a gas collection efficiency of 60%, resulting in total cost savings of 1.6 million USD. Besides, this study forecasted waste generation and equivalent electricity generation potential for the next two decades, as shown in Table 4. The potential for waste generation and equivalent electricity generation has been estimated based on the waste generation trend from 2014 to 2020.

Apart from landfills, by practicing composting alone, GHG emissions can be reduced to 12.8%50 by diverting food. According to FAO (2015)51, 3.5 Gt CO2e of greenhouse gas emissions per year are reported due to food waste. The composting (Anaerobic Digestion) process begins with the hydrolysis of complex organic polymers into simple soluble molecules, followed by fermentation to a mixture of short-chain volatile fatty acids and further conversion of these organic acids to acetate, eventually resulting in methane production52.

The result of composting in Brunei Darussalam can produce 5384 tonnes of CO2e/year (Table 5) and thus assist in eliminating environmental footprints and pollution.

Therefore, the critical analysis and potential benefits of tapping landfill gas with composting demonstrate a promising result. There is a need to develop a framework for waste management policy in Brunei Darussalam to reap the benefits.

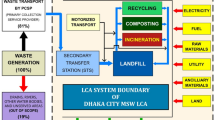

With its weaknesses identified in this study, the existing waste management system emphasises developing a framework where various stakeholders have specific roles and responsibilities. The schematic diagram (Fig. 4) indicates the proposed framework for the waste management system. The JASTRe and municipality are responsible for collecting information on the amount and types of waste generated monthly and developing a database for auditing. These include identifying existing waste management gaps and planning and creating actions. Various educational or research institutes further assist this task by identifying relevant stakeholders and setting their roles and responsibilities. JASTRe then liaises among various stakeholders to execute the proposed plan and actions. Auditing and monitoring are done to verify the performance of the waste management framework every 3 years. Based on the feedback on the framework, it was redesigned to improve the effectiveness of the policy.

On the other hand, several factors need to be considered in formulating the policy, including the type of intervention, actions, outcome of an action, time frame, and responsible stakeholders, as shown in Table 6.

Following the National Land Use Master Plan (2008), the formulation of suggested system configurations for solid waste management had already been planned and developed for Rancangan Kemajuan Negara (RKN) 9 (Ninth National Development Plan 2007–2012). The issues and delays in the implementation of improved solid waste management have been carried forward to RKN 10 (10th National Development Plan 2012–2017), RKN 11 (11th National Development Plan 2018–2022 and RKN 12 (12th National Development Plan 2023–2027). This study has distinguished gaps (target-specific tasks, lack of clear roles and responsibilities, and proposed a policy framework. The type of policy/intervention needed to formulate sustainable waste management is to be implemented by involving all the government institutions, such as JASTRe, MoD, MoF, MoH, Municipal Department, educational institutions, private sectors, and NGOs with their integration and roles and responsibilities specified. We should move forward and implement integrated solid waste management, which agrees with the vision of Wawasan Brunei 2035 (Brunei Vision 2035) towards a quality life for the people. We must reduce its waste at the source to achieve such a goal. Thus, it is recommended that the authority develop the waste segregation act.

Promote hierarchy of waste management

Brunei Darussalam can move up the solid waste management hierarchy, where the greatest potential lies in the composting section. As residents are already willing to separate waste and are not new to recycling, policies must incorporate a sustainable solid waste management system. Suppose more awareness is given to promote the solid waste management hierarchy. In that case, Brunei Darussalam will have greater potential to move away from the bottom of the hierarchy and move to the top towards source reduction.

Increase community awareness through environmental education

According to Aseto54, a building block to a successful waste management program is knowledge/awareness of waste streams. This awareness will provide an effective waste reduction strategy that targets the most promising and problematic waste materials. Environmental education should start early but not be restricted to this age category. Instead, it must be directed towards all demographic levels, focusing on improving awareness and concern about the environment and public health through effective public participation. Establishing public education campaigns can cause a behavioural shift to support future changes in relevant policies related to solid waste management in Brunei Darussalam. Allowing environmental education from childhood through schools and other higher education institutions (HEIs) can help raise awareness and thus develop positive environmental attitudes that link the environment to sustainable practices. Waste-related costs fell by around £125 k between 2004 and 2008 at HEIs in the U.K., and a recycling rate of 72% was achieved due to the strategy developed at HEIs to promote sustainable waste management55. Figure 5 shows the Strategies for Sustainable Solid Waste Management.

Encourage voluntary recycling targets for commerce and industry

Industries should be given targets on how much material to recycle annually. It also allows industries to promote an efficient solid waste management system in Brunei Darussalam. Commercial areas and industries have an ongoing impact on both residents and the public. This can already be seen through the plastic bag bans during weekends at specific supermarkets, thus influencing the consumer to reuse and recycle.

Introduce economic incentives

Economic incentives are particularly effective in changing behaviour and improving waste diversion. Milea50 states that economic incentives provide financial rewards for cooperation. Economic incentives such as packaging tax may aid in waste reduction, encourage recycling, and have a greater positive impact on waste reduction and recycling than public awareness and recycling programs.

Policies for the recycling industry

Policies occur in the form of regulations, enforcement of laws, and incentives. One example is the use of "garbage banks" in Thailand or "Trash banks" in Jakarta. Garbage banks or trash banks were implemented to improve community-level recycling, and participants were rewarded with money and goods in exchange for recycled materials.

No national license system for recycling business is present in Brunei Darussalam. The national authority should establish a licensing system to exclude informal and illegal recyclers without environmentally sound waste/resource management to promote public health and reduce environmental risk. Also, the Government should develop policies that regulate role sharing and the cost burden of stakeholders for recycling, based on the PPP (polluter pays principle), to provide financial support to authorized recyclers. Without such official regulations, the recycling industry in Brunei Darussalam is very sensitive to resource market prices since their income for recycling services comes mainly from resource sale profit and not from authorized tipping fees. The resource price reduction negatively impacts the recycling business and is unsustainable. Government should consider an authorised recycling route that closes the recycling loop domestically. Trade data (Table 2) mentions that Brunei exported 50% of plastic waste to China and Hong Kong for downstream recycling in 2016; however, this flow will be stopped because the China Waste Import Ban started at the beginning of 2018. This example shows the necessity of establishing a material loop in the domestic market.

Small-scale or local composting initiatives

Residents rely on burning to manage garden waste in the area. Although this reduces the quantity of waste produced and disposed of, burning waste negatively impacts public health and the environment. The local community may initiate community composting programs, where the supply of the waste to generate compost comes from the residents providing a constant supply of garden waste, and much of the success of such programs depends on the demand for the final product.

Countries that exhibit comparable solid waste characteristics to Brunei frequently have common traits such as high levels of affluence, urbanization, and consumption patterns, with their economies mostly dependent on oil and gas. Some countries that may display comparable waste characteristics are Kuwait (1.5 kg per person per day)56, Qatar (1.8 kg per person per day)57, Bahrain ((1.74 kg per person per day)58, and the United Arab Emirates (1.7 kg per person per day)59, where similar research can be conducted. Formulating a waste management system is important, considering that the stakeholders in those countries may differ based on the governance system. The emissions generated by these countries because of fossil fuel usage are substantial. Hence, effective waste management can decrease methane emissions from landfills, thereby alleviating the impact of climate change. As the waste management policy proposes, it can also produce revenue by implementing recycling programs and waste-to-energy projects, which require collaboration among many stakeholders.

Future challenges and prospective of waste management initiatives in Brunei Darussalam

Utilising methane for energy recovery can assist Brunei in diversifying its electricity generation and moving it away from reliance on oil and gas. Brunei should promote using energy recovery methods from waste to enhance waste management, minimize environmental consequences, enhance economic growth, ensure energy security, and promote circularity. After critically reviewing the current waste management in Brunei Darussalam, the study has identified (1) Legislations and regulations: enacts a legislative structure that requires the implementation of appropriate waste management standards, establishes rules and criteria for the management, processing, and elimination of waste, defines responsibility and imposes sanctions for failure to comply; (2) Proper implementation and enforcement: effectively implements laws and regulations, extensive monitoring and enforcement to assure compliance, stop unlawful dumping and promotes public trust and waste management policy adherence; (3) Provision of adequate facilities for the waste management: builds recycling centres, waste-to-energy facilities, encourages innovative technology to boost efficiency; (4) Adequate training and knowledge: increases public knowledge of waste minimization, segregation, and disposal, invites households, businesses, and industries to collaborate, promotes sustainability and environmental responsibility among all stakeholders; and (5) Waste audit: regularly evaluates waste generation and management, identifies areas for improvement and tracks progress, provides data to improve policies and initiatives based on accountability.

It is recommended that policymakers establish clear, enforceable waste management legislation from generation to disposal, encourage sustainability through waste management tax benefits, grants, and subsidies, and encourage producers to recycle and dispose of their products. Investors should promote sustainable waste management technology and companies through investment. Promote Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) by investing in waste management companies and jointly fund significant waste management infrastructure projects with governments and NGOs. Practitioners such as waste management companies are recommended to accept best practices, train staff on new rules and technology, help customers sort and recycle waste, keep operations transparent, and disclose waste management performance and improvements. While the public is encouraged to minimise single-use plastics and other disposable materials, practice segregation, recycle and compost organic waste, and purchase eco-friendly recyclable products.

The policy framework has been developed based on the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, which requires validation through a questionnaire survey involving relevant stakeholders to ensure utmost coordination and cooperation. Project permits and regulatory clearances for waste-to-energy recovery projects can be complicated and time-consuming. Environmental and regulatory requirements can stall project progress. Therefore, future studies should focus on validating the waste management framework through feedback from relevant stakeholders. Tax subsidies and renewable energy feed-in tariffs are crucial to investment. Comprehensive environmental, economic, and social strategies are needed to address these limits.

Conclusion

Sustainable solid waste management must first be prioritized for sustainable development in Brunei Darussalam. In the proposed waste management policy, emphasis has been given to segregating waste at the doorsteps and recovering waste as resources through WtE (alternative energy) with an electricity generation potential of 8.6% of the total energy produced by harnessing the gas to generate 367 GWh of electricity, an annual savings of 1.6 million USD can be achieved. The potential for landfill gas for WtE is significant in energy security and environmental integrity. Besides, any decisions related to solid waste management must signify the participation of all stakeholders at all levels to address all issues related to solid waste and its implications.

Data availability

The corresponding author has all the data connected to this work. All data or inquiries connected to this study can be acquired by contacting the corresponding author.

References

UNDP, Data|Human Development Reports, (2023). https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2003 Accessed on July. 2023.

Onu, C. Sustainable Waste Management in Developing Countries, Biennial Congress of the Institute of Waste Management of Southern Africa 1 367–378 (Cape Town, 2000).

UN-MEA, The U.N. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Report, (2006). http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200607/cmselect/cmenvaud/77/77.pdf. Accessed on 15 August 2020.

Ramsar, The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Background and Context to the Development of Principles and Guidance for the Planning and Management of Urban and Peri-urban Wetlands (COP11 DR11), (2012), http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/cop11/doc/cop11-doc23-e-urban.pdf. Accessed on 19 November 2013.

Karak, T., Bhagat, R. M. & Bhattacharyya, P. Municipal solid waste generation, composition, and management: The world scenario, critical reviews. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42(15), 1509–1630 (2012).

World Bank. Brief: Solid waste management. (2018) http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/brief/solid-waste-management Acessed on 18 December 2021.

UN-HABITAT. Solid Waste Management in the World Cities, Earthscan, pp. 184 (2010).

Singh, A. Sustainable waste management through systems engineering models and remote sensing approaches. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2(3), 1105–1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-022-00151-3 (2022).

Ahsan, A., Alamgir, M., Shams, S., Rowshon, M. K. & Daud, N. N. N. Assessment of municipal solid waste management system in a developing country. Chin. J. Eng. 1, 561935 (2014).

Shams, S. & Ibrahimu, C. Household waste recovery and recycling: A case study of Kigoma-Ujiji Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Develop. 2(4), 412–424 (2003).

IPCC. IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. Hayama, Japan: IPCC/IGES, (2006). http://www.ipccnggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/ppd.htm. Acessed on 12 December 2021.

Ngoc, U. N. & Schnitzer, H. Sustainable solutions for solid waste management in Southeast Asian countries. Waste Manag. 29, 1982–1995 (2009).

Wilson, D. C., Smith, N. A., Blakey, N. C. & Shaxson, L. Using research-based knowledge to underpin waste and resources policy. Waste Manag. Res. 25(3), 247–256 (2007).

Benyam, A., Kinnear, S. & Rolfe, J. Integrating community perspectives into domestic food waste prevention and diversion policies. Resources Conserv. Recycling 134, 174–183 (2018).

Schanes, K., Dobernig, K. & Burcu, G. B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Product. 182, 978–991 (2018).

Mourad, M. Recycling, recovering and preventing “food waste”: Competing solutions for food systems sustainability in the United States and France. J. Cleaner Product. 126, 461–477 (2016).

JASTRe Solid waste management in negara Brunei Darussalam, (October) (2006).

Yunos, R., Tarip, Z., and Salleh, N. The Second Meeting of Regional 3R Forum Concept in Brunei Darussalam (2010).

Hoornweg, D. & Bhada-Tata, P. What a Waste: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management (Urban Development & Local Government Unit, World Bank, 2012).

Shams, S., Guo, Z., & Juani, R. Integrated and sustainable solid waste management for Brunei Darussalam (2014). https://doi.org/10.1049/cp.2014.1066. Acessed on 13 December 2021.

UNEP. Waste Management in ASEAN Countries (2017).

Popov, V., Itoh, H., & Brebbia, C. A. Waste management and the environment VI, WITtransaction on ecology and the environment, Vol. 163. W.I.T. Press (2012).

Boldrin, A., Andersen, K. J., MØller, J., Christensen, H. T. & Favoino, E. Composting and compost utilization: Accounting of greenhouse gases and global warming contributions. Waste Manag. Res. 27(8), 800–812 (2009).

Amlinger, F., Peyr, S. & Cuhls, C. Greenhouse gas emissions from composting and mechanical biological treatment. Waste Manag. Res. 26(1), 47–60 (2008).

Gomes, P. A., Nunes, I. M., Vitoriano, C. C., & Pedrosa, E. Co-composting of biowaste and poultry waste. Italy: ISWA Publication (2017). http://www.iswa.it/materiali/iswa_apesb_2009/1-209_FP.pdf. Acessed on 15 December 2021.

Chandrappa, R., and Das, D. B. Solid waste management, environmental science and engineering, 59. (Springer-Verlag, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28681-0_2. Acessed on 5 December 2021.

Reynaud, A., Markantonis, V., Moreno, C. C., N'Tcha M'Po, Y., Sambienou, G.G., Adandedji, F. M., Afouda, A., Euloge Kossi Agbossou, E. K., and Mama, D. Combining Expert and Stakeholder Knowledge to Define Water Management Priorities in the Mékrou River Basin, Combining Expert and Stakeholder Knowledge to Define Water Management Priorities in the Mékrou River Basin (2015).

Mani, S. & Singh, S. Sustainable municipal solid waste management in India: A policy agenda. Procedia Environ. Sci. 35, 150–157 (2016).

Bingham, L. B., Nabatchi, T. & O’Leary, R. The new governance: Practices and processes for stakeholder and citizen participation in the work of Government. Public Adm. Rev. 65(5), 547–558 (2005).

Amanda Yap. Plastic bag habits yet to change. The Brunei Times. (2018). https://www.btarchive.org/news/national/2014/01/15/plastic-bag-habits-yet-change. Acessed on 15 December 2021.

https://resourcetrade.earth/. Acessed on 15 December 2021.

https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution. Acessed on 15 December 2021.

Korai, M. S. & Uqaili, M. A. The feasibility of municipal solid waste for energy generation and its existing management practices in Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 72, 338–353 (2017).

Ogunjuyigbe, A. S. O., Ayodele, T. R. & Alao, M. A. Electricity generation from municipal solid waste in some selected cities of Nigeria: An assessment of feasibility, potential and technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 80, 149–162 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Effectiveness of waste-to-energy approaches in China: From the perspective of greenhouse gas emission reduction. J. Clean. Product. 163, 99–105 (2017).

Malinauskaite, J. et al. Municipal solid waste management and waste-to-energy in the context of a circular economy and energy recycling in Europe. Energy 141, 2013–2044 (2017).

Rajaeifar, M. A. et al. Electricity generation and GHG emission reduction potentials through different municipal solid waste management technologies: A comparative review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 79, 414–439 (2017).

Moya, D., Aldás, C., López, G. & Kaparaju, P. Municipal solid waste as a valuable renewable energy resource: A worldwide opportunity of energy recovery by using Waste-To- Energy Technologies. Energy Procedia 134, 286–295 (2017).

Brunner, P. & Rechberger, H. Waste to energy—Key element for sustainable waste management. Waste Manag. 1, 1–10 (2014).

Di Matteo, U., Nastasi, B., Albo, A. & Astiaso Garcia, D. Energy contribution of OFMSW (organic fraction of municipal solid waste) to energy-environmental sustainability in urban areas at small scale. Energies 10(2), 229 (2017).

Yi, S., Jang, Y.-C. & An, A. K. Potential for energy recovery and greenhouse gas reduction through waste-to-energy technologies. J. Cleaner Product. 176, 503–511 (2018).

Ohnishi, S., Fujii, M., Ohata, M., Rokuta, I. & Fujita, T. Efficient energy recovery through a combination of waste-to-energy systems for a low-carbon city. Resources Conserv. Recycling 28, 394–405 (2018).

Bong, P. et al. Review on the renewable energy and solid waste management policies towards biogas development in Malaysia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 70, 988–998 (2017).

Zuberi, M. J. S. & Ali, S. F. Greenhouse effect reduction by recovering energy from waste landfills in Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 44, 117–131 (2015).

Martire, S., Mirabella, N. & Sala, S. Widening the perspective in greenhouse gas emissions accounting: The way forward for supporting climate and energy policies at municipal level. J. Clean. Product. 176, 842–851 (2018).

CEIC (2016). https://www.ceicdata.com/en/brunei/energy-generation-consumption-and-sale/electricity-generation, Accessed on May 21, 2018.

GMI, International Best Practices Guide for Landfill Gas Energy Projects. G.M.I. Publisher (2012).

Bourn, M., Robinson, R., Innocenti, F. & Scheutz, C. Regulating landfills using measured methane emissions: An English perspective. Waste Manag. 87, 860–869 (2019).

Duan, Z., Kjeldsen, P. & Scheutz, C. Efficiency of gas collection systems at Danish landfills and implications for regulations. Waste Manag. 139, 269–278 (2022).

Seng, B. & Kaneko, H. Benefit of composting application over landfill on municipal solid waste management in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. W.I.T. Trans. Ecol. Environ. 163, 63–72 (2012).

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2015). Global Initiative on Food Waste and Waste Reduction. Retrieved from June 18 2017. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4068e.pdf.

Kibler, K. M., Reinhart, D., Hawkins, C., Motlagh, M. A. & Wright, J. Food waste and the food-energy-water nexus: A review of food waste management alternatives. Waste Manag. 74, 52–62 (2018).

JPKE, 2016 Available at Department of Economic Planning and Development-Population (JPKE).

Aseto, A. S. Waste Management in Higher Institutions: A Case Study of University of Nairobi, Kenya (2009). 2017 http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/99283/SUSAN%20ATIENO%20ASETO.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed on July 2, 2023.

Milea, A. Waste as a social dilemma: Issues of social and environmental justice and the role of residents in municipal solid waste management, Delhi, India. Master's thesis, Lund University. Lund, Sweden (2009).

Al-Jarallah, R. & Aleisa, E. A baseline study characterizing the municipal solid waste in the State of Kuwait. Waste Manag. 34(5), 952–960 (2014).

Mariyam, S., Cochrane, L., Zuhara, S. & McKay, G. Waste management in Qatar: A systematic literature review and recommendations for system strengthening. Sustainability 14(15), 8991 (2022).

Zafar, S. Solid Waste Management in Bahrain, Solid Waste Management in Bahrain | EcoMENA, (2023). https://www.ecomena.org/solid-waste-bahrain/. Accessed on July 24, 2024.

Zafar, S. Waste management outlook for the Middle East. The Palgrave Handbook of Sustainability: Case Studies and Practical Solutions. 159–181 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shahriar Shams: (conceptualization), methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, resources, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. Jaya Narayan Sahu and Nabisab Mujawar Mubarak: formal analysis, validation, writing review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shams, S., Sahu, J.N. & Mubarak, N.M. A route for energy recovery from municipal solid waste and developing a framework for waste management in Brunei Darussalam. Sci Rep 14, 19767 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70845-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70845-1